The Impact of Religiosity and Food Consumption Culture on Food Waste Intention in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

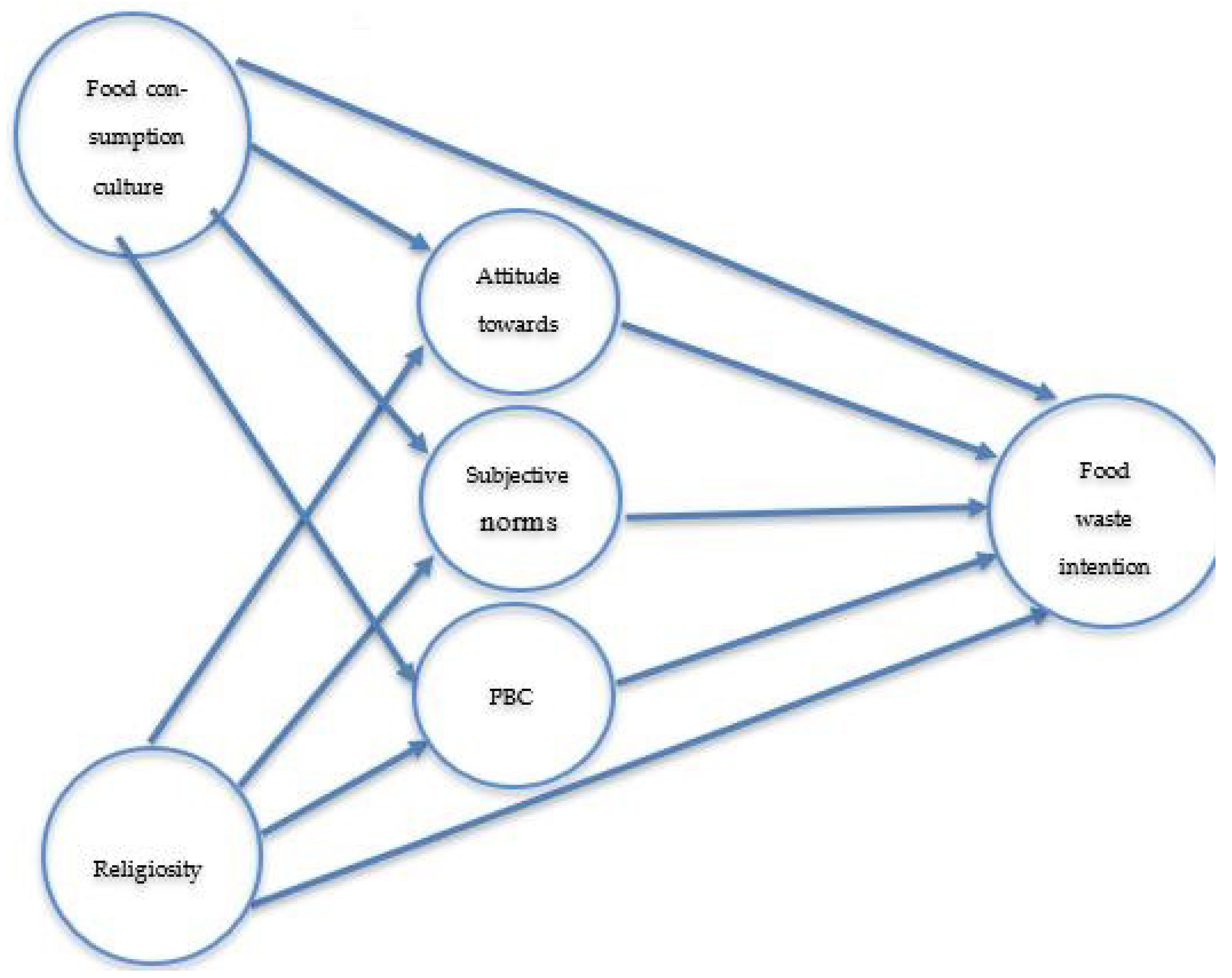

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Concepts of Food Waste, Religiosity, and Food Consumption Culture

2.2. Religiosity and Food Waste Intention

2.3. Food Consumption Culture and Food Waste Intention

2.4. The Role of Attitude in the Relationship between Religiosity/Food Consumption Culture and Food Waste Intention

2.5. The Role of Subjective Norm in the Relationship Between Religiosity/Food Consumption Culture and Food Waste Intention

2.6. The Role of Perceived Behavioral Control in the Relationship between Religiosity/Food Consumption Culture and Food Waste Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Instrument Measurement

3.2. Data Collection

4. The Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Opportunities for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Annual Report. United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2011–2012. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/corporate/annual-report-2011-2012--the-sustainable-future-we-want.html (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- United Nations Development Program UNDP. Food Waste Index Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO. Food Loss and Food Waste. 2019. Available online: http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food Wastage Footprint—Impacts on Natural Resources; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Predicting household food waste reduction using an extended theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 20, 101–194. [Google Scholar]

- Parizeau, K.; Massow, V.; Martin, R. Household-level dynamic of food waste production and related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in Guelph, Ontario. J. Waste Manag. 2015, 35, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Environment Water and Agriculture; Media Center. Available online: https://www.mewa.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News242020.aspx (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Baig, M.B.; Al-Zahrani, K.H.; Schneider, F.; Straquadine, G.S.; Mourad, M. Food waste posing a serious threat to sustain-ability in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia—A systematic review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelradi, F. Food Waste behavior at the household level: A conceptual framework. J. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhuian, N.; Sharma, K.; Butt, I.; Ahmed, U. Antecedents and pro-environmental consumer behavior (PECB): The moderating role of religiosity. J. Consum. Mark. 2018, 35, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, A.; Jeffrey Xie, H.; Gurel-Atay, E.; Kahle, R. Greening up because of god: The relations among religion, sustainable consumption and subjective well-being. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggiotto, F.; Mason, M.C.; Moretti, A. Religiosity, materialism, consumer environmental predisposition. Some insights on vegan purchasing intentions in Italy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoushy, S.; Jang, S. Religiosity and food waste reduction intentions: A conceptual model. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirbekk, V.; Connor, P.; Stonawski, M.; Hackett, P. The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050. Pew Research Center, 2015. Available online: https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2015/03/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Zamri, B.; Azizal, A.; Nakamura, S.; Okada, K.; Nordin, H.; Othman, Á.; Akhir, N.; Sobian, A.; Kaida, N.; Hara, H. Delivery, impact and approach of household food waste reduction campaigns. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhlis, S. Relevancy and Measurement of Religiosity in Consumer Behavior Research. Int. Bus. Res. 2009, 2, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Alhaija, S.; Yusof, R.; Hashim, H.; Jaharuddin, S. The motivational approach of religion: The significance of religious orientation on customer behavior. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2017, 12, 609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Reisinger, Y.; Moufakkir, O. Cultural issues in tourism, hospitality and leisure in the Arab/Muslim world. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 9, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, L.; Tonjes, L. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, A.; Spiker, L.; Truant, L. Wasted Food: U.S. Consumers’ reported awareness, attitudes, and behaviors. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollan, M. Unhappy Meals. New York Times. 28 January 2007. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/01/28/magazine/28nutritionism.t.html (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Musaiger, O. Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting food consumption patterns in the Arab countries. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 1993, 113, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis): New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Kruglanski, W. Reasoned action in the service of goal pursuit. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 126, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, W.; Turn, S.; Flachsbart, P. Characterization of food waste generators: A Hawaii case study. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 2483–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, B.; Hanson, C.; Lomax, J.; Kitinoja, L.; Waite, R. Reducing Food Loss and Waste. Working Paper; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 45. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwala, R.; Mishra, P.; Singh, R. Religiosity and consumer behavior: A summarizing review. J. Manag. Spirit. Relig. 2019, 16, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delener, N. The Effects of Religious Factors on Perceived Risk in Durable Goods Purchase Decisions. J. Consum. Mark. 1990, 7, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, N.; Mizerski, D. The constructs mediating religions’ influence on buyers and consumers. J. Islam. Mark. 2010, 1, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Youssef, M.M.H.; Kortam, W.; Abou-Aish, E.; El-Bassiouny, N. Effects of religiosity on consumer attitudes toward Islamic banking in Egypt. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 786–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathras, D.; Cohen, B.; Mandel, N.; Mick, G. The effects of religion on consumer behavior: A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 26, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, W.; Burnett, J. Consumer religiosity and retail store evaluative criteria. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1990, 18, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 100–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fourst, L. Food Culture: Tradition and Modernity in Conflict. Food: Work and Culture; SIFO Delrapport 4 Mat: Arbeid og Kultur [Food: Work and Culture]; National Institute for Consumer Research: Lysaker, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sillitoe, P.; Misnad, S. Sustainable Development: An appraisal focusing on the Gulf Region; Berghan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Kaneesamkandi, Z. Biodegradable waste to biogas: Renewable energy option for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2013, 4, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Abusin, S.; Lari, N.; Khaled, S.; Al Emadi, N. Effective policies to mitigate food waste in Qatar. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 15, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Vitell, S.; Ramos-Hidalgo, E.; Rodríguez-Rad, C. A Spanish perspective on the impact on religiosity and spirituality on consumer ethics. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forghani, M.H.; Kazemi, A.; Ranjbarian, B. Religion, peculiar beliefs and luxury cars’ consumer behavior in Iran. J. Islam. Mark. 2019, 10, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakrachakarn, V.; Moschis, P.; Ong, S.; Shannon, R. Materialism and life satisfaction: The role of religion. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ansari, S. Improving solid waste management in gulf co-operation council states: Developing integrated plans to achieve reduction in greenhouse gases. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2012, 62, 376–387. [Google Scholar]

- Essoo, N.; Dibb, S. Religious Influences on Shopping Behavior: An Exploratory Study. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Shahbaz, S. The Relationship between Religiosity and New Product Adoption. J. Islam. Mark. 2010, 1, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, A.; Johnson, A.; Liu, L. Religiosity and special food consumption: The explanatory effects of moral priorities. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.H.; Vogel, C. Religion and trust: An experimental study. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, A.; Kahle, R.; Kim, H. Religion and motives for sustainable behaviors: A cross-cultural comparison and contrast. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, M.; Al-Thani, A.-A.; Al-Mahdi, N.; Al-Kareem, H.; Barakat, D.; Al-Chetachi, W.; Tawfik, A.; Akram, H. An Overview of Food Patterns and Diet Quality in Qatar: Findings from the National Household Income Expenditure Survey. Cureus 2017, 9, 1249–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boughanmi, H.; Kodithuwakku, S.; Weerahewa, J. Food and Agricultural Need to Reduce Food Waste: Experts. 2014. Available online: http://www.arabnews.com/saudiarabia/news/722026 (accessed on 5 April 2021).

- Stefan, V.; Van Herpen, E.; Tudoran, A.A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, M.; Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite 2011, 57, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J. Consumer perception and trends about health and sustainability: Trade-offs and synergies of two pivotal issues. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching-Hsu, H.; Shih-Min, L.; Nai-Yun, H. Understanding Global Food Surplus and Food Waste to Tackle Economic and Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 28–92. [Google Scholar]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behavior: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visschers, M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behavior: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, E.; Marsh, E.; Stunell, D.; Parry, D. Spaghetti soup: The complex world of food waste behaviors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, M.; Mutum, S.; Ariswibowo, N. Impact of religious values and habit on an extended green purchase behavior model. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food waste matters—A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysseldyk, R.; Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. Religiosity as Identity: Toward an Understanding of Religion from a Social Identity Perspective. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 14, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Knox, K.; Burke, K.; Bogomolova, S. Consumer perspectives on household food waste reduction campaigns. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, V.; Young, W.; Unsworth, L.; Robinson, C. Bringing habits and emotions into food waste behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautish, P.; Paul, J.; Sharma, R. The moderating influence of environmental consciousness and recycling intentions on green purchase behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, E.; Sahin, H.; Topaloglu, Z.; Oledinma, A.; Huda, A.K.S.; Irani, Z.; Sharif, A.M.; Wout, T.V.; Kamrava, M. A consumer behavioural approach to food waste. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Arabia General Authority for Statistics. Tourism Establishments Survey. 2018. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa/sites/default/files/nshrlmnshatlsyhylm2018en-cplrq.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Ibeh, K.I.N.; Brock, J.U.; Zhou, J. The drop and collect survey among industrial populations: Theory and empirical evidence. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Cramer, D. Quantitative Data Analysis with IBM SPSS 17, 18 & 19: A Guide for Social Scientists; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modelling: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, R.; Lomax, R. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, A.E. Values and religious issues in psychotherapy and mental health. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.; Costantinao, M. A Hierarchical Pyramid for Food Waste Based on a Social Innovation Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Närvänen, E.; Mesiranta, N.; Sutinen, U.-M.; Mattila, M. Creativity, aesthetics and ethics of food waste in social media campaigns. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichon, I.; Boccato, G.; Saroglou, V. Nonconscious influences of religion on prosociality: A priming study. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton-Peset, A.; Fernandez-Zamudio, M.-A.; Pina, T. Promoting Food Waste Reduction at Primary Schools. A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruia, L.; Florescu, G.; Opera, O.B.; Tane, N. Reducing Environmental Risk by Applying a Polyvalent Model of Waste Management in the Restaurant Industry. Sustaiability 2021, 13, 5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, H.E.; Harlow, L.L.; Mulaik, S.A. Causation issues in structural equation modeling research. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1994, 1, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N = 1135 | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 885 | 78 |

| Female | 250 | 22 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 227 | 20 |

| Married | 817 | 72 | |

| Others (e.g., Divorced, Widowed) | 91 | 8 | |

| Age | Less than 30 Years Old | 238 | 21 |

| 30 to 45 Years | 624 | 55 | |

| 46 to 60 Years | 216 | 19 | |

| More than 60 Years | 57 | 5 | |

| Education Level | High School Degree | 204 | 18 |

| University Graduate | 738 | 65 | |

| Post-Graduate | 193 | 17 | |

| Abbrevation | Items | N | Min. | Max. | M | S.D | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religiosity [10]. | ||||||||

| Religiosity _1 | My faith involves all of my life | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.82 | 1.254 | −0.982 | −0.055 |

| Religiosity _2 | In my life, I experience the presence of God | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.74 | 1.273 | −0.879 | −0.306 |

| Religiosity _3 | I am religious person and I let religious considerations influence my everyday affairs | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.77 | 1.252 | −0.917 | −0.146 |

| Religiosity _4 | Nothing is as important to me as serving God as best as I know-how | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.77 | 1.259 | −0.953 | −0.112 |

| Religiosity _5 | My religious beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.74 | 1.268 | −0.899 | −0.219 |

| Religiosity _6 | I try hard to carry my religion over into all my other dealings in life | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.73 | 1.272 | −0.887 | −0.260 |

| Religiosity _7 | One should seek God’s guidance when making every important decision | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.73 | 1.273 | −0.870 | −0.311 |

| Food consumption culture [63]. | ||||||||

| FCC_1 | It is my culture to serve a lot of food to show my hospitaliy | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.51 | 0.974 | −0.923 | 0.713 |

| FCC_2 | I have a tendency to buy a few more food products than I need at the restaurant | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.51 | 0.950 | −0.861 | 0.629 |

| FCC_3 | I serve more food than can be eaten to show my hospitality | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.53 | 0.937 | −0.891 | 0.824 |

| Attitudes toward behaviors [63]. | ||||||||

| ATB_1 | I feel bad when uneaten food is thrown away | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.62 | 1.274 | −0.506 | −0.875 |

| ATB_2 | I was raised to believe that food should not be wasted | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.59 | 1.280 | −0.485 | −0.890 |

| ATB_3 | I think food should not be wasted | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.60 | 1.272 | −0.485 | −0.881 |

| ATB_4 | Throwing away food bothers me | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.58 | 1.300 | −0.485 | −0.918 |

| Subjective norms [63]. | ||||||||

| SN_1 | My friends think my efforts towards reducing food waste are necessary | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.55 | 1.268 | −0.449 | −0.913 |

| SN_2 | My family thinks my efforts towards reducing food waste are necessary | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.57 | 1.230 | −0.452 | −0.857 |

| SN_3 | My friends think my efforts towards preparing food from leftovers are necessary | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.59 | 1.213 | −0.414 | −0.881 |

| SN_4 | My family thinks my efforts towards preparing food from leftovers are necessary | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.60 | 1.236 | −0.468 | −0.869 |

| Perceived behavioral control [63]. | ||||||||

| PBC_1 | I find it difficult to store food at high temperatures | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.64 | 0.817 | −0.859 | 1.054 |

| PBC_2 | I find it difficult to store food in its required conditions | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.60 | 0.846 | −0.843 | 0.689 |

| PBC_3 | I find it difficult to store certain type of food products | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.69 | 0.740 | −0.553 | 0.160 |

| PBC_4 | I find it difficult to shop for food products for one person | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.66 | 0.808 | −0.933 | 1.228 |

| Food waste intention [63]. | ||||||||

| FWI_1 | I have no intention to eat leftover food | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.34 | 0.996 | −0.481 | −0.190 |

| FWI_2 | I throw away trimmings’ food | 1135 | 1 | 6 | 3.24 | 1.064 | −0.393 | −0.112 |

| FWI_3 | I do not generate as little food waste as possible | 1135 | 1 | 5 | 3.09 | 1.129 | −0.224 | −0.515 |

| FWI_4 | I have no intention to find a use for food trimmings | 1135 | 1 | 6 | 3.06 | 1.191 | −0.247 | −0.675 |

| Factors and Variables | Loading | CR | AVE | MSV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Religiosity (a = 0.986) | 0.986 | 0.909 | 0.113 | 0.954 | ||||||

| Religiosity _1 | 0.953 | |||||||||

| Religiosity _2 | 0.947 | |||||||||

| Religiosity _3 | 0.976 | |||||||||

| Religiosity _4 | 0.952 | |||||||||

| Religiosity _5 | 0.957 | |||||||||

| Religiosity _6 | 0.943 | |||||||||

| Religiosity _7 | 0.947 | |||||||||

| 2-Food Consumption Culture (a = 0.954) | 0.955 | 0.876 | 0.151 | 0.213 | 0.936 | |||||

| FCC_1 | 0.902 | |||||||||

| FCC_2 | 0.937 | |||||||||

| FCC_3 | 0.968 | |||||||||

| 3-Attitudes toward Behaviors (a = 0.981) | 0.981 | 0.927 | 0.178 | 0.324 | 0.499 | 0.963 | ||||

| ATB_1 | 0.972 | |||||||||

| ATB_2 | 0.958 | |||||||||

| ATB_3 | 0.975 | |||||||||

| ATB_4 | 0.947 | |||||||||

| 4-Subjective Norms (a = 0.982) | 0.982 | 0.933 | 0.178 | 0.354 | 0.372 | 0.279 | 0.966 | |||

| SN_1 | 0.953 | |||||||||

| SN_2 | 0.981 | |||||||||

| SN_3 | 0.963 | |||||||||

| SN_4 | 0.966 | |||||||||

| 5-Perceived Behavioral Control (a = 0.937) | 0.938 | 0.791 | 0.247 | 0.213 | 0.216 | 0.332 | 0.397 | 0.890 | ||

| PBC_1 | 0.877 | |||||||||

| PBC_2 | 0.875 | |||||||||

| PBC_3 | 0.907 | |||||||||

| PBC_4 | 0.899 | |||||||||

| 6-Food Waste Intention (a = 0.926) | 0.928 | 0.763 | 0.151 | 0.410 | 0.388 | 0.333 | 0.357 | 0.207 | 0.874 | |

| FCC_1 | 0.823 | |||||||||

| FCC_2 | 0.908 | |||||||||

| FCC_3 | 0.864 | |||||||||

| FCC_1 | 0.897 | |||||||||

| Hypotheses | Beta (β) | C-R (T-value) | R2 | Hypo. Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Religiosity food waste intention | −0.11 | −1.910 | Not Supported | |

| H2 | Food consumption culture | 0.54 *** | 9.989 | Supported | |

| H3 | Religiosity attitude toward behavior Food waste intention | Path 1: β = 0.22 *** Path 2: β = −0.36 *** | Path 1: t-value = 3.421 Path 2: t-value = −5.123 | Supported | |

| H4 | Religiosity subjective Norms Food waste intention | Path 1: β = 0.25 *** Path 2: β = −0.39 *** | Path 1: t-value = 3.160 Path 2: t- value = −5.966 | Supported | |

| H5 | Religiosity Perceived behavior control Food waste intention | Path 1: β = −0.27 *** Path 2: β = 0.41 *** | Path 1: t-value = −3.461 Path 2: t-value = 7.233 | Supported | |

| H6 | Food consumption culture attitude toward behavior Food waste intention | Path 1: β = −0.32 *** Path 2: β = −0.36 *** | Path 1: t-value = −4.560 Path 2: t-value = −5.199 | Supported | |

| H7 | Food consumption culture subjective norms Food waste intention | Path 1: β = −0.32 *** Path 2: β = −0.39 *** | Path 1: t-value = −4.140 Path 2: t-value = −6.209 | Supported | |

| H8 | Food consumption culture perceived behavior controlFood waste intention | Path 1: β = 0.44 *** Path 2: β = 0.41 *** | Path 1: t-value = 7.328 Path 2: t-value = 7.111 | Supported | |

| Food waste intention | 0.75 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elshaer, I.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Alyahya, M.; Abu Elnasr, A. The Impact of Religiosity and Food Consumption Culture on Food Waste Intention in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116473

Elshaer I, Sobaih AEE, Alyahya M, Abu Elnasr A. The Impact of Religiosity and Food Consumption Culture on Food Waste Intention in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116473

Chicago/Turabian StyleElshaer, Ibrahim, Abu Elnasr E. Sobaih, Mansour Alyahya, and Ahmed Abu Elnasr. 2021. "The Impact of Religiosity and Food Consumption Culture on Food Waste Intention in Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116473

APA StyleElshaer, I., Sobaih, A. E. E., Alyahya, M., & Abu Elnasr, A. (2021). The Impact of Religiosity and Food Consumption Culture on Food Waste Intention in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 13(11), 6473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116473