Urbanization, Touristification and Verticality in the Andes: A Profile of Huaraz, Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

No region, no locality in the country can be described today without noting its close dependence on or connection to every other place in the country. If that is the case, then all the regions that we once categorized as “nature” have ultimately become part of the city.[1] (p. 103)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study Method

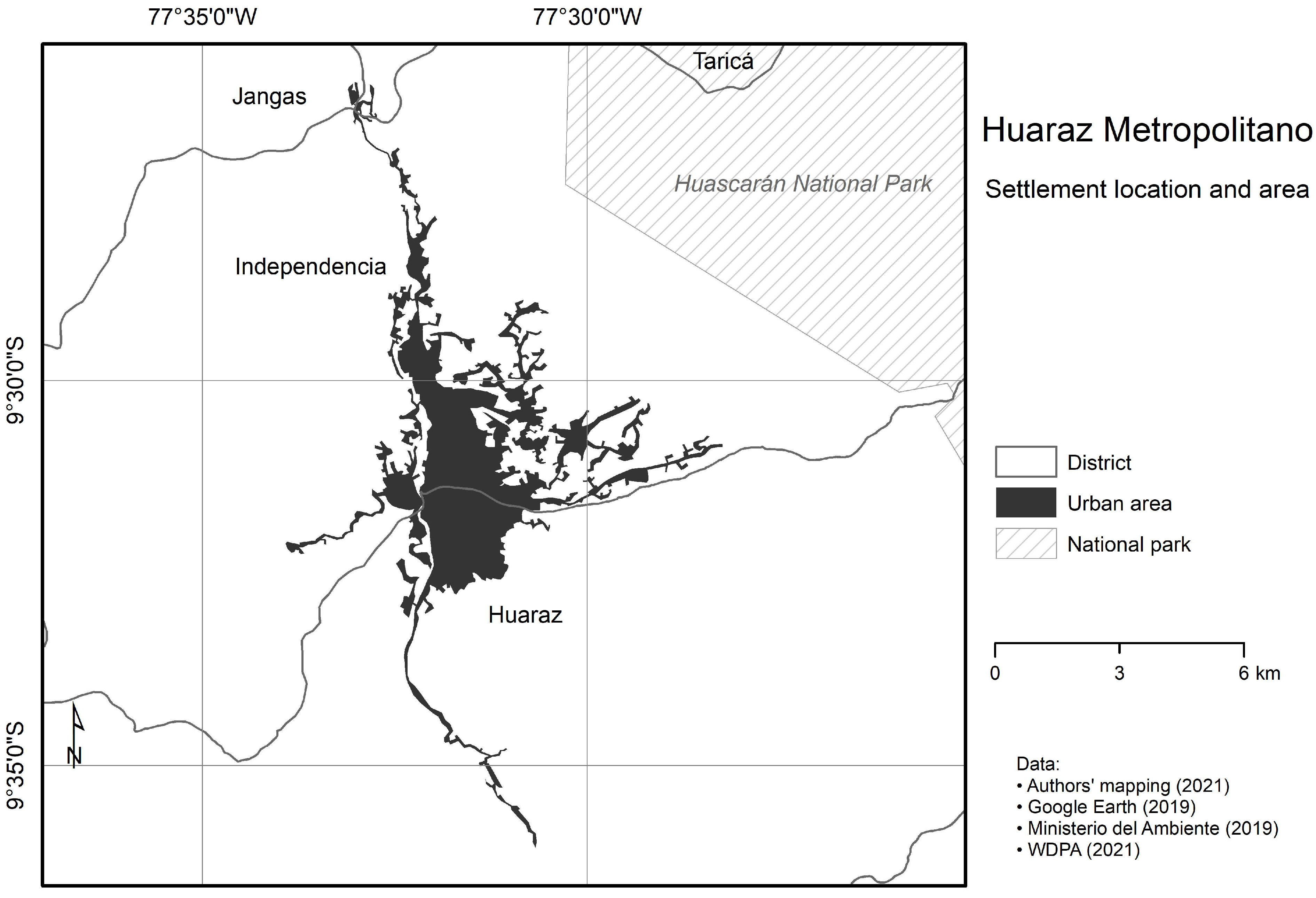

2.2. Study Area: Geographic Location and Character

3. The Relevance of Verticality: Urbanizing Archipelagos and Touristification

4. Nature and Culture in Space and Time: towards an Urbanizing Center of Tourism

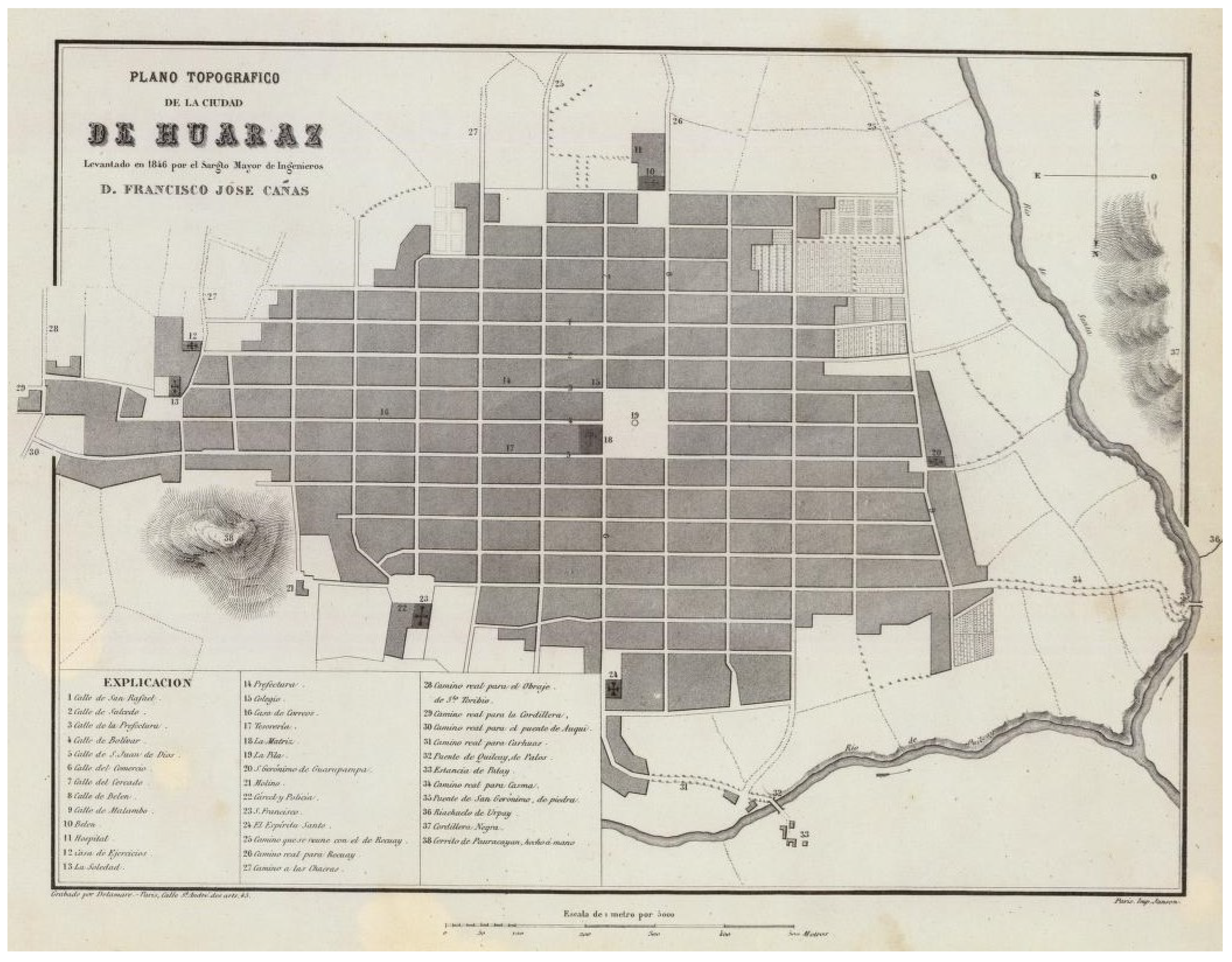

4.1. Foundation and Colonial Period

4.2. From Independence to Disaster

4.3. From Disaster to Heritagization

The fertile valley is gentle. Fields of potatoes and yellow grains cover the low hills in a quilted landscape. The pungent smell of eucalyptus permeates the clear air, and the bell and bleat of the grazing sheep can be heard for miles. The Indian peasants who inhabit the valley are a colorful people. The women thresh wheat in their homespun skirts, tossing the chaff high in the air. There are frequent processions with trumpet and drum through the streets of Huaraz, the main town and marketplace of the valley. A two-day tour up and down the valley affords the visitor a view of life in the interior of Peru that contrasts strikingly with the modern urban life of Lima. The 20-room Hotel Los Pinos at Huaraz, managed by a French couple, offers fine lodging with good food.[65]

5. A Postmodern Present: Peaks as Peri-Urban Parks?

5.1. The Horizontal View: Key Figures on Population, Settlement and Tourism

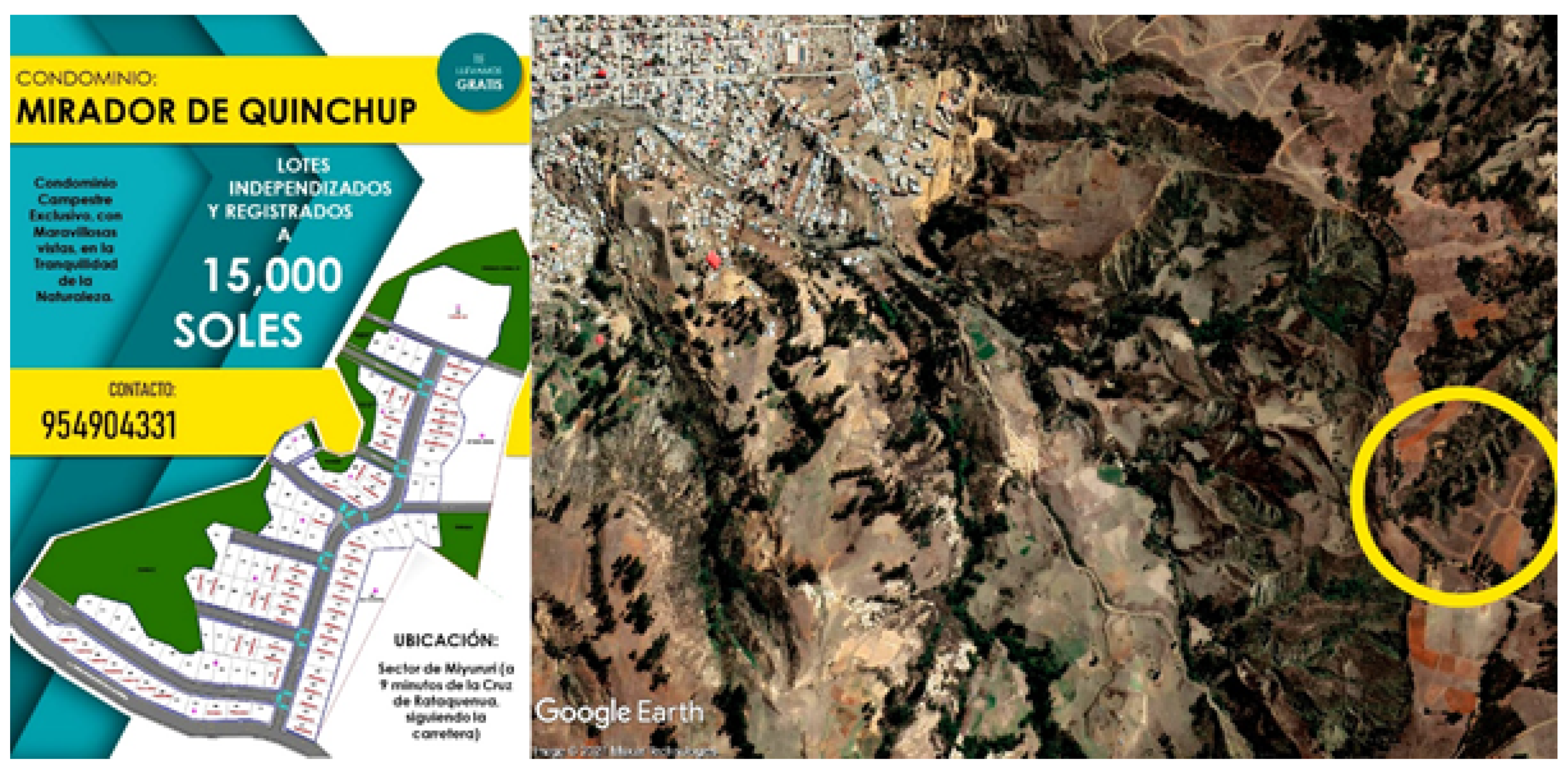

5.2. The Vertical View: Touristification and the Urban Reproduction of Complementary Archipelagos

provides an account of a change in status of tourist practices and destinations in the context of globalization and post-modernity; amenity migrations […] and new residential practices […], a calling into question of the tourist utopia and uchronia, a search for continuity between holiday practices (recreational, social, cultural, spatial etc.) and everyday practices […], the touristification of ordinary places, experimental tourism and neo-situationism, new relationships between town and mountain in the context of metropolization.[92] (p. 84)

6. Conclusions

- 1.

- bridge the urban–rural divide, considering mountain agriculture and campesinos (“peasants”) as integrated parts of past, present and future “urban development” and as pillars of tourism,

- 2.

- beware of outdated center–periphery juxtapositions, for Huaraz Metropolitano and the Santa Valley are developing into a polycentric urban area and tourism destination and

- 3.

- overcome the valley–upland dichotomy, acknowledging that Huaraz Metropolitano is turning into a postmodern, vertically organized tourist city that integrates the “operational landscape” of Huascarán National Park up to the highest peaks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IGP | Instituto Geofísico del Perú |

| INEI | Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática |

| UPT | Urban Population Threshold |

References

- Meili, M. Is the Matterhorn City? In Implosions/Explosions. Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization; Brenner, N., Ed.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino, C.; Buyck, J. The Mountain Metropolis’s Land Design Project. Grenoble, from Plain to Slope. J. Alp. Res. Rev. Géogr. Alp. 2018, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A.; Andexlinger, W.; Bender, O. City profile: Innsbruck. Cities 2020, 97, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorf, A.; Stadel, C. The Andes. A Geographical Portrait; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, D. The urban and the rural in Puno, highland Peru. Anthropol. Tod. 2019, 35, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, D.; Haller, A. Cusco: Profile of an Andean city. Cities 2021, 113, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A.; Borsdorf, A. Huancayo Metropolitano. Cities 2013, 31, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G. Mining and tourism: Urban transformations in the intermediate cities of Cajamarca and Cusco, Peru. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2013, 40, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, F.O. Montology manifesto: Echoes towards a transdisciplinary science of mountains. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 2512–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitmann, J. Introduction: Urban environmental profile series. Cities 1994, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitmann, J. A global synthesis of seven urban environmental profiles. Cities 1995, 12, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J.B. A hundred city profiles. Cities 2003, 20, 295–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorf, A. Geographisch Denken und Wissenschaftlich Arbeiten; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, D. Curiosity, Inquiry, and the Geographical Imagination; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orum, A.M.; Feagin, J.R.; Sjoberg, G. Introduction: The nature of the case study. In A Case for the Case Study; Feagin, J.R., Orum, A.M., Sjoberg, G., Eds.; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1991; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kanai, J.M.; Schindler, S. Regional urbanization: Emerging approaches and debates. In Handbook of the Geographies of Regions and Territories; Paasi, A., Harrison, J., Jones, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 322–331. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E. Accentuate the regional. Int. J. Urb. Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsdorf, A.; Haller, A. Urban montology: Mountain cities as transdisciplinary research focus. In The Elgar Companion to Geography, Transdisciplinarity and Sustainability; Sarmiento, F.O., Frolich, L.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 140–154. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. XII Censo de Población y VII de Vivienda; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pulgar Vidal, J. Geografía del Perú. Las Ocho Regiones Naturales, la Regionalización Transversal, la Sabiduría Ecológica Tradicional; Peisa: Lima, Peru, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stadel, C. Altitudinal belts in the tropical Andes: Their ecology and human utilization. Benchmark Yearb. Conf. Lat. Am. Geogr. 1992, 17/18, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, A.; Branca, D. Montología: Una perspectiva de montaña hacia la investigación transdisciplinaria y el desarrollo sustentable. Rev. Investig. Altoand. 2020, 22, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología. Datos Hidrometeorológicos a Nivel Nacional. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200520085500/https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=estaciones (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- IGP. Anta. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200619202811/http://met.igp.gob.pe/clima/HTML/anta.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Murra, J.V. Formaciones Económicas y Políticas del Mundo Andino; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Lima, Peru, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. Planetary urbanization. In Urban Constellations; Gandy, M., Ed.; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. The ‘urban age’ in question. Int. J. Urb. Reg. Stud. 2013, 38, 731–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City 2015, 19, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequera, J.; Nofre, J. Shaken, not stirred. New debates on touristification and the limits of gentrification. City 2018, 22, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troll, C. Die geographischen Grundlagen der andinen Kulturen und des Incareiches. Ibero-Am. Arch. 1931, 5, 258–294. [Google Scholar]

- Gade, D. Carl Troll on Nature and Culture in the Andes. Erdkunde 1996, 50, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, S.B. El lugar del hombre en el ecosistema andino. Rev. Mus. Nac. 1974, XL, 279–302. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, S.B. Man’s Use of an Andean Ecosystem. Hum. Ecol. 1976, 4, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti-Molinié, A. Variations actuelles sur un vieux thème andin: L’idéal vertical. Étud. Rur. 1981, 81–82, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, S.H. The future of value of the verticality concept: Implications and possible applications in the Andes. In Actes du XLIIe Congrès International des Américanistes; Fondation Singer-Polignac: Paris, France, 1978; pp. 234–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, E. Remapping the Vertical Archipelago: Mobility, Migration, and the Everyday Labor of Andean Development. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2017, 23, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, A.; Ho, R. Livelihood and migration patterns at different altitudes in the Central Highlands of Peru. Clim. Dev. 2014, 6, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babb, F.E. ‘The real indigenous are higher up’: Locating race and gender in Andean Peru. Lat. Am. Caribb. Ethn. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadel, C. Horizontal and Vertical Archipelagoes of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Andean Realm. In Sustainability Assessment at the 21st Century; Bastante-Ceca, M.J., Fuentes-Bargues, J.L., Hufnagel, L., Mihai, F.L., Iatu, C., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A. The “sowing of concrete”: Peri-urban smallholder perceptions of rural–urban land change in the Central Peruvian Andes. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingman, E.; Bretón, V. Las fronteras arbitrarias y difusas entre lo urbano-moderno y lo rural-tradicional en los Andes. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2017, 22, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinsky, W. The Hypothesis of the Mobility Transition. Geogr. Rev. 1971, 61, 219–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte-Mór, R.; Castriota, R. Extended urbanization: Implications for urban and regional theory. In Handbook of the Geographies of Regions and Territories; Paasi, A., Harrison, J., Jones, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Perlik, M. Alpine gentrification: The mountain village as a metropolitan neighbourhood. J. Alp. Res. Rev. Géogr. Alp. 2011, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, R. Introduction to London: Aspects of Change Centre for Urban Studies; Macgibbon and Kee: London, UK, 1964; [reprinted in Glass, R. Cliches of Urban Doom; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989; pp. 132–158]. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, M.; Lees, L. New-Build ‘Gentrification’ and London’s Riverside Renaissance. Environ. Plan. A: Econ. Sp. 2005, 37, 1165–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofre, J.; Martins, J.C. The Disneyfication of the neoliberal urban night. Keep Simple Make Fast 2017, 1, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rick, J.W. Chavin culture (pre-Moche). In The Encyclopedia of Empire; Wiley: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.F. The Recuay Culture of Peru’s North-Central Highlands: A Reappraisal of Chronology and Its Implications. J. Field Archaeol. 2004, 29, 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, W.H. Wari (Huari) culture. In The Encyclopedia of Empire; Wiley: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärssinen, M. Tawantinsuyu, el Estado Inca y su Organización políTica; Institut Français d’Études Andines/Fondo Editorial de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, France/Peru: Lima, Peru, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bonavia, D. The South American Camelids; Cotsen Institute of Archaelogy Monograph: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Porras Barrenechea, R. Los Cronistas del Perú (1528–1650) y Otros Ensayos; Biblioteca Clásicos del Peru/2. Ediciones del Centenario; Banco de Crédito del Perú: Lima, Peru, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- de Estete, M. La relación del viaje que hizo el señor capitán Hernando Pizarro por mandado del señor Gobernador, su hermano, desde el pueblo de Caxamalca a Parcama y de allí a Jauja. Verdadera relación de la conquista del Perú y provincia del Cuzco llamada la Nueva Castilla. In Biblioteca Peruana; Tomo, I., Ed.; Técnicos Asociados: Lima, Peru, 1968; pp. 242–257. [Google Scholar]

- de León, P.C. Crónicas del Perú. El señOrío de los Incas; Biblioteca Ayacucho: Caracas, Venezuela, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza Soriano, W. Huaraz: Poder, Sociedad y Economia en los Siglos XV y XVI: Reflexiones en Torno a las Visitas de 1558, 1594 y 1712; Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Seminario de Historia Rural Andina: Lima, Peru, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lliboutry, L.; Arnao, B.M.; Pautre, A.; Schneider, B. Glaciological Problems Set by the Control of Dangerous Lakes in Cordillera Blanca, Peru. I. Historical Failures of Morainic Dams, their Causes and Prevention. J. Glaciol. 1977, 18, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, F. Huarás: Visión Integral; Safori: Huaraz, Peru, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Raimondi, A. El Departamento de ANCACHS y sus Riquezas Minerales; Enrique Meiggs: Lima, Peru, 1873. [Google Scholar]

- Middendorf, E.W. Perú: Observaciones y Estudios del país y sus Habitantes Durante una Permanencia de 25 años; Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos: Lima, Peru, 1973–1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dobyns, H.F. The Struggle for Land in Peru: The Hacienda Vicos Case. Ethnohist 1966, 13, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurner, M. From Two Republics to One Divided: Contradictions of Postcolonial Nationmaking in Andean Peru; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA; London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, S.A. Lo que el agua se llevó: Consecuencias y Lecciones del Aluvión de Huaraz de 1941; Ministerio del Ambiente/Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, T. L’invention occidentale de la haute montagne andine. Mappemonde 2005, 79, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- A scenic drive into the Andes out of Lima. New York Times. 1964. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20210426120416/https://www.nytimes.com/1964/11/08/archives/a-scenic-drive-into-the-andes-out-of-lima.html (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Carey, M. In the Shadow of Melting Glaciers. Climate Change and Andean Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Grötzbach, E. Tourism in the Cordillera Blanca Region, Peru. Rev. Geogr. 2003, 133, 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Smith, A.; Hoffman, S. (Eds.) The Angry Earth: Disaster in Anthropological Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sagav, M. The Interface Between Earthquake Planning and Development Planning: A Case Study and Critique of the Reconstruction of Huaraz and the Callejon de Huaylas, Ancash, Peru, Following the 31 May 1970 Earthquake. Disasters 1979, 3, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.L. National parks, conservation, and agrarian reform in Peru. Geogr. Rev. 1980, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourke, M.J. Parque Nacional Huascarán, Cordillera Blanca, Peru. Am. Alp. J. 1976, 20, 376–379. [Google Scholar]

- Obad Šćitaroci, M.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B. Heritage Urbanism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas Asín, F. Una Historia del Turismo en el Perú; Universidad de San Martín de Porres: Lima, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber Rodríguez, J.M.; Neyra Rojas, F.I. Migración y desarrollo urbano de la ciudad de Huaraz. Aporte Santiaguino 2019, 2, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Residencial Montecristo/Residencial Los Ángeles de Pashpa Fondo mi vivienda s.a. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20210421084434/https://www.mivivienda.com.pe/PortalWEB/usuario-busca-viviendas/buscador-detalle.aspx?op=nstp&nom=&dep=ANCASH&pro=HUARAZ&dis=TARICA&amin=&amax=&pmin=&almin=&almax=&pmax=&bv=0&exp=0 (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Julca Guerrero, F.; Nivin Vargas, L. Una aproximación al desarrollo sociocultural de Huaraz. Saber Discursivo 2020, 1, 106–121. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare, G.; Barret, H. Regional inequalities in the Peruvian tourist industry. Geogr. J. 1999, 165, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEI. VIII Censo de Población y III de Vivienda; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. IX Censo de Población y IV de Vivienda; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. XI Censo de Población y VI de Vivienda; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Borsdorf, A. Cómo modelar el desarrollo y la dinámica de la ciudad latinoamericana. EURE 2003, 29, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, L.; Baur, R.; Csaplovics, E. Urban sprawl and fragmentation in Latin America: A dynamic quantification and characterization of spatial patterns. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 115, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Centeno, P. Los efectos urbanos de la minería en el Perú: Del modelo de Cerro de Pasco y La Oroya al de Cajamarca. Apuntes 2011, 38, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Low, S. Cultural meaning of the plaza: The history of the Spanish-American gridplan-plaza urban design. In The Cultural Meaning of the Urban Space; Rotenberg, R., McDonogh, G., Eds.; Greenwood: Westport, CT, USA, 1993; pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rama, Á. La Ciudad Letrada; Ediciones del Norte: Hannover, NH, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Holzner, L. Stadtland USA: Die Kulturlandschaft des American Way of Life; Justus Perthes Verlag: Gotha, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Construirán Teleférico que Permitirá Apreciar Cordillera Blanca en Huaraz. Andina. Agencia Peruana de Noticias. 2012. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20210421085035/https://andina.pe/agencia/noticia-construiran-telefericopermitira-apreciar-cordillera-blanca-huaraz-425308.aspx (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Graham, J.; Keil, R. Natürlich städtisch: Stadtumwelten nach dem Fordismus: Ein nordamerikanisches Beispiel. Prokla 1997, 27, 567–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, P.W.; Gill, A.M. Chura, Branding mountain destinations: The battle for “placefulness”. Tour. Rev. 2004, 59, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The condition of postmodernity; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M. From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Brand. 2004, 1, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdeau, P. The Alps in the age of new style tourism: Between diversification and post-tourism? In Managing Alpine future. Proceedings of the Innsbruck Conference 15–17 October 2007; Borsdorf, A., Stötter, J., Veulliet, E., Eds.; Austrian Academy of Sciences Press: Innsbruck, Austria, 2009; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar]

| District | Population (Count) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 1993 | 2007 | 2017 | |

| Huaraz | 70,001 | 44,771 | 56,186 | 65,005 |

| Independencia | 0 | 47,614 | 62,853 | 80,610 |

| Jangas | 3268 | 3569 | 4403 | 4971 |

| Taricá | 4533 | 4743 | 5394 | 6959 |

| Total | 77,802 | 100,697 | 128,836 | 157,545 |

| District | Dwellings (Count) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 1993 | 2007 | 2017 | |

| Huaraz | 13,579 | 10,564 | 15,294 | 18,888 |

| Independencia | 0 | 11,049 | 19,177 | 25,182 |

| Jangas | 792 | 1323 | 1592 | 1985 |

| Taricá | 1036 | 1279 | 1860 | 2663 |

| Total | 15,407 | 24,215 | 37,923 | 48,718 |

| District | Quechua (%) | Aymara (%) | White (%) | Mestizo (%) | Other (%) | Total (Count) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huaraz | 49.77 | 0.15 | 3.41 | 43.94 | 2.74 | 48,911 |

| Independencia | 58.77 | 0.15 | 3.05 | 35.49 | 2.54 | 60,060 |

| Jangas | 72.81 | 0.03 | 3.22 | 21.72 | 2.22 | 3821 |

| Taricá | 67.78 | 0.04 | 3.18 | 27.36 | 1.63 | 4898 |

| Total | 55.86 | 0.14 | 3.21 | 38.21 | 2.58 | 117,690 |

| Year | Incoming Visitors (Count) | Domestic Visitors (Count) | Total Visitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 6000 | 62,536 | 68,536 |

| 2007 | 33,782 | 111,200 | 144,982 |

| 2008 | 23,998 | 84,932 | 108,930 |

| 2009 | 31,071 | 66,278 | 97,349 |

| 2010 | 32,067 | 79,852 | 111,919 |

| 2011 | 33,185 | 93,635 | 126,820 |

| 2012 | 33,950 | 103,584 | 137,534 |

| 2013 | 35,758 | 112,818 | 148,576 |

| 2014 | 38,799 | 139,063 | 177,862 |

| 2015 | 48,971 | 200,189 | 249,160 |

| 2016 | 66,264 | 194,887 | 261,151 |

| 2017 | 85,773 | 197,596 | 283,369 |

| Element | Example | Function | Altitudinal Zone | Type of Urbanization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gated condominiums | El Pinar (District of Independencia) | About 280 rental houses (3250 m) for employees of the mining company Antamina. Point of attraction for further real-estate projects like El Nuevo Pinar and recreation centers (e.g., El Bosque). Includes services, e.g., an international school. | Quechua | Concentrated |

| La Alborada (District of Taricá) | About 100 freehold houses (2800 m) originally built by the Barrick mining company for some of its employees. The former school has a new operator. Today, dwellings are also used for short-term vacation rental. | Quechua | Concentrated | |

| Ecotourism lodges | Churup Mountain Lodge (District of Independencia) | Ecotourism lodge (3680 m) built by European immigrants, specializing in wellness treatments (incl. “soul cleansing”) and trekking in Huascarán National Park. | Suni | Extended |

| Lazy Dog Inn (District of Independencia) | Ecotourism lodge (3620 m) built by North American immigrants, offering inter-cultural experiences, trekking and social responsibility/sustainability through close economic links with local communities. | Suni | Extended | |

| Mountain huts | Refugio Ishinca (District of Independencia) | Andean hut (4600 m) for trekking and mountaineering tourists, built and operated by the Catholic non-profit organization Operazione Mato Grosso from Italy. About 60 beds, also offers breakfast, lunch, dinner, toilets, hot showers and electricity. | Puna | Extended |

| Vivaque Longoni (District of Taricá) | Andean hut (5000 m) for trekking and mountaineering tourists, built and operated by the Catholic non-profit organization Operazione Mato Grosso from Italy. About 18 beds. No staff present and no other services offered. | Janca | Extended |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Branca, D.; Haller, A. Urbanization, Touristification and Verticality in the Andes: A Profile of Huaraz, Peru. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116438

Branca D, Haller A. Urbanization, Touristification and Verticality in the Andes: A Profile of Huaraz, Peru. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116438

Chicago/Turabian StyleBranca, Domenico, and Andreas Haller. 2021. "Urbanization, Touristification and Verticality in the Andes: A Profile of Huaraz, Peru" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116438

APA StyleBranca, D., & Haller, A. (2021). Urbanization, Touristification and Verticality in the Andes: A Profile of Huaraz, Peru. Sustainability, 13(11), 6438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116438