Brand Personality Traits of World Heritage Sites: Text Mining Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. World Heritage Marketing Perspective and Visitor Knowledge

2.2. Brand Personality Construct

2.3. Concept of Brand Personality in Relation to Brand Identity and Image

2.4. Brand Personality in Tourism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Question

3.2. Analytical Procedure

3.3. Data Preparation

4. Results

4.1. Dictionary Customisation for WHSs

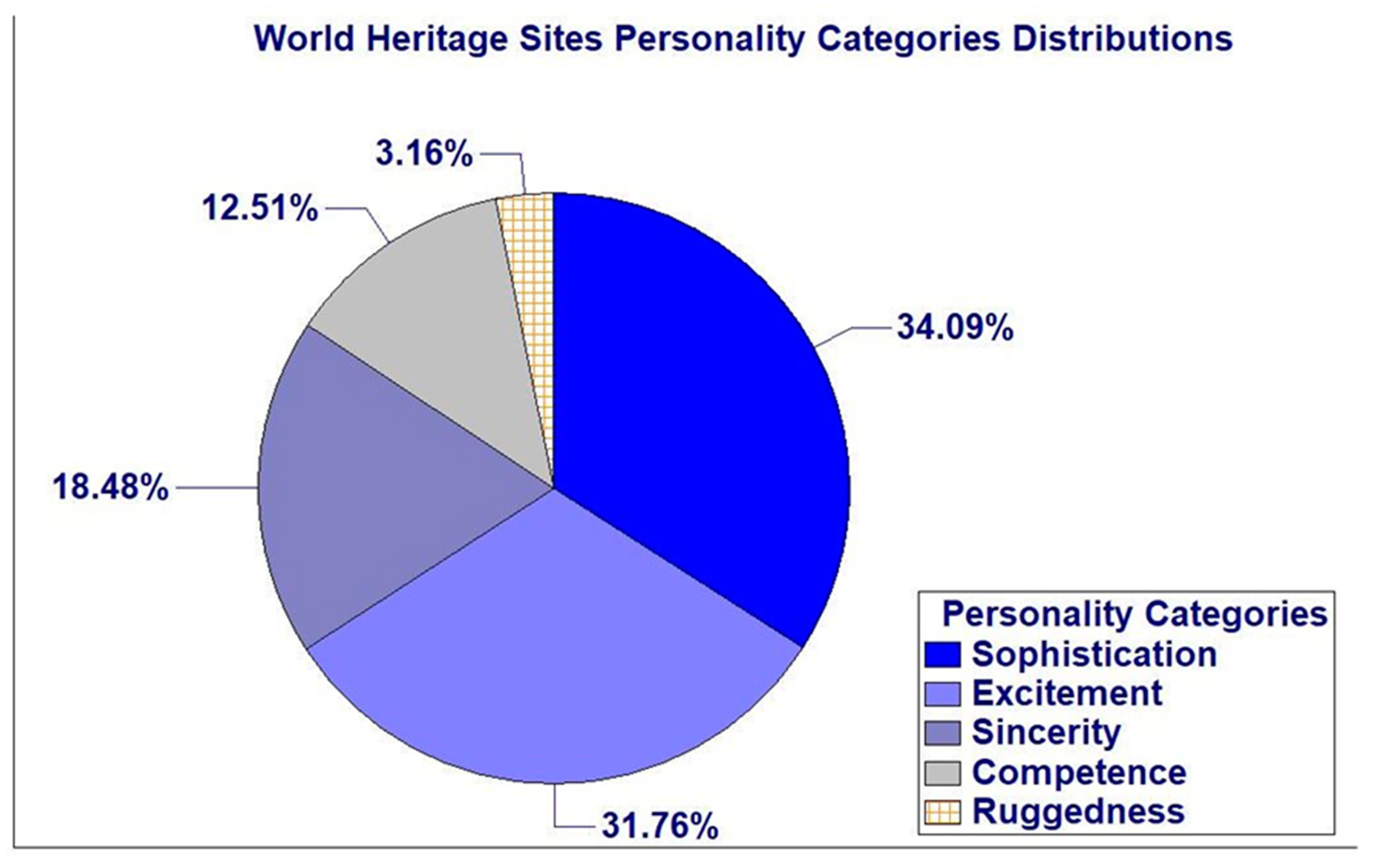

4.2. World Heritage Personality Distribution on TripAdvisor

4.3. Relationship between World Heritage Sites and their Overall Personality Dimensions

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. World Heritage Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Theoretical Contribution to Brand Personality

5.3. Methodological Contributions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ryan, J.; Silvanto, S. Study of the Key Strategic Drivers of the Use of the World Heritage Site Designation as a Destination Brand. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.-S.; Bak, S.; Min, C. Do UNESCO Heritages Attract More Tourists? World J. Manag. 2015, 6, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Tourism and Natural World Heritage: A Complicated Relationship. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B.A.; Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G. World Heritage as a Placebo Brand: A Comparative Analysis of Three Sites and Marketing Implications. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xue, L.; Jones, T.E. Tourism-Enhancing Effect of World Heritage Sites: Panacea or Placebo? A Meta-Analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B.A.; Hall, C.M. Who Visits World Heritage? A Comparative Analysis of Three Cultural Sites. J. Herit. Tour. 2016, 12, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.; Fournier, S. A Brand as a Charchater, a Partner and Person:Question of Brand Personaity. Adv. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Radler, V.M. 20 Years of Brand Personality: A Bibliometric Review and Research Agenda. J. Brand Manag. 2018, 25, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Hosany, S. Destination Personality: An Application of Brand Personality to Tourism Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Cao, F.; Chen, X. Recognise Me from Outside to inside: Learning the Influence Chain of Urban Desti-nation Personalities. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of Brand Personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccrae, R.R.; John, O.P. An Introduction to the Five-Factor Model and Its Application. Personality 1992, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, G.; Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Whelan, S.; Mete, M.; Loo, T. Brand Personality: Theory and Dimensionality. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, L.F.; Opoku, R.; Hultman, M.; Abratt, R.; Spyropoulou, S. What I Say about Myself: Communication of Brand Personality by African Countries. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moya, M.; Jain, R. When Tourists Are Your ‘Friends’: Exploring the Brand Personality of Mexico and Brazil on Facebook. Public Relat. Rev. 2013, 39, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarhoff, G.; Kleyn, N. Open Source Brands and Their Online Brand Personality. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 20, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, R.; Abratt, R.; Pitt, L. Communicating Brand Personality: Are the Websites Doing the Talking for the Top South African Business Schools? J. Brand Manag. 2006, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papania, L.; Campbell, C.; Opoku, R.A.; Styven, M.; Berthon, J.P. Using Brand Personality to Assess Whether Biotechnology Firms Are Saying the Right Things to Their Network. J. Commer. Biotechnol. 2008, 14, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschen, J.; Pitt, L.; Kietzmann, J.; Dabirian, A.; Farshid, M. The Brand Personalities of Brand Communities: An Analysis of Online Communication. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.R.; Siguaw, J.A.; Mattila, A.S. A Re-Examination of the Generalizability of the Aaker Brand Personality Measurement Framework. J. Strateg. Mark. 2003, 11, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L.; Benet-Martinez, V.; Garolera, J. Consumption Symbols as Carriers of Culture: A Study of Japanese and Spanish Brand Personality Constructs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Nayak, J.K. Destination Personality: Scale Development and Validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaudo, G.; Figini, P. The Puzzle of Tourism Demand at Destinations Hosting UNESCO World Heritage Sites: An Analysis of Tourism Flows for Italy. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellini, R. Is UNESCO Recognition Effective in Fostering Tourism? A Comment on Yang, Lin and Han. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimura, T. The Impact of World Heritage Site Designation on Local Communities—A Case Study of Ogimachi, Shirakawa-Mura, Japan. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuepper, D.; Patry, M. The World Heritage List: Which Sites Promote the Brand? A Big Data Spatial Econometrics Approach. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-H.; Lin, H.-Y. Revisiting the Relationship between World Heritage Sites and Tourism. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B.A. Franchising Our Heritage: The UNESCO World Heritage Brand. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.M.; Halpenny, E.A. Communicating the World Heritage brand: Visitor awareness of UNESCO’s World Heritage symbol and the implications for sites, stakeholders and sustainable management. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 768–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Tsaur, J.R.; Yang, C.H. Does World Heritage List Really Induce More Tourists? Evidence from Macau. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1450–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuepper, D. What Is the Value of World Heritage Status for a German National Park? A Choice Experiment from Jasmund, 1 Year after Inscription. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing and Measuring, Brand Managing Customer-Based Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wall, G.; Xu, X.; Han, F.; Du, X.; Liu, Q. Is It Better for a Tourist Destination to Be a World Heritage Site? Visitors’ Perspectives on the Inscription of Kanas on the World Heritage List in China. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 23, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, N.; Hazen, H.; Thapa, B. Visitor Perceptions of World Heritage Value at Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Nepal. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Reichel, A.; Cohen, R. Tourists Perceptions of World Heritage Site and Its Designation. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 272–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, G.W. Animism, or Thought Currents of Primitive Peoples; Library of Alexandria: Alexandria, Egypt, 1919; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, J.M. Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior: A Critical Review Reproduced with Permission of the Copyright Owner. Further Reproduction Prohibited without Permission. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Astous, A.; Boujbel, L. Positioning Countries on Personality Dimensions: Scale Development and Implications for Country Marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Murphy, S.A.; Papadopoulos, N. The U.S. Brand Personality: A Sino Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1028–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.D.; Yurt, O.; Guneri, B.; Kurtulus, K. Branding Places: Applying Brand Personality Concept to Cities. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 1286–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heere, B. A New Approach to Measure Perceived Brand Personality Associations Among Consumers. Sport Mark. Q. 2010, 19, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, G.; Chun, R.; da Silva, R.V.; Roper, S. A Corporate Character Scale to Assess Employee and Customer Views of Organization Reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2004, 7, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Astous, A.; Lévesque, M. A Scale for Measuring Store Personality. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.; Moscardo, G.; Benckendorff, P. Using Brand Personality to Differentiate Regional Tourism Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschnabel, P.A.; Krey, N.; Babin, B.J.; Ivens, B.S. Brand management in higher education: The University Brand Personality Scale. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3077–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, A.; Kapferer, J.N. Do Brand Personality Scales Really Measure Brand Personality? J. Brand Manag. 2003, 11, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuens, M.; Weijters, B.; de Wulf, K. A New Measure of Brand Personality. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, R.S. Destination Personality and Destination Image: A Literature Review. IUP J. Brand Manag. 2018, 15, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J.N. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaur, S.H.; Yen, C.H.; Yan, Y.T. Destination brand identity: Scale development and validation. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. Influence of Consumer Personality, Brand Personality, and Corporate Personality on Brand Preference: An Empirical Investigation of Interaction Effect. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2016, 28, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, H.M.M. Who Really Creates the Place Brand? Considering the Role of User Generated Content in Creating and Communicating a Place Identity. Commun. Soc. 2018, 31, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mccrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Validation of the Five-Factor Model of Personality across Instruments and Observers. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S. The Impact of Destination Personality Dimensions on Destination Brand Awareness and Attractiveness: Australia as a Case Study. Tourism 2012, 60, 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Phou, S. A Closer Look at Destination: Image, Personality, Relationship and Loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Kannan, D.; Ruci, L. The Japan Brand Personality in China: Is It All Negative among Consumers? Place Branding Public Dipl. 2019, 15, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location Upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, A.L. Discovering Brand Magic: The Hardness of the Softer Side of Branding. Int. J. Advert. 1997, 16, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeff, T.R. Consumption situations and the effects of brand image on consumers’ brand evaluations. Psychol. Mark. 1997, 14, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Ekinci, Y.; Uysal, M. Destination image and destination personality. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2007, 1, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A.; Baloglu, S. Brand Personality of Tourist Destinations: An Application of Self-Congruity Theory. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Exploring the Relationship between Destination Image & Brand Personality of a Tourist Destination—An Application of Projective Techniques. J. Travel Tour. Res. 2007, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, D.; Apostolopoulou, A.; Kaplanidou, K. Destination Personality, Affective Image, and Behavioral Intentions in Domestic Urban Tourism. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.K.; Lee, J.S. Toward the Perspective of Cognitive Destination Image and Destination Personality: The Case of Beijing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyals-Mirabent, S.; Mohammadi, L. City Brand Projected Personality: A New Measure to Assess the Consistency of Projected Personality across Messages. Commun. Soc. 2018, 31, 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A.; Iacobucci, D. Marketing Research Spring 2006. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 34, 294–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Méndez, J.I.; Hine, M.J. Countries’ Positioning on Personality Traits. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 23, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO World Heritage Center. 2021. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/ (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Wiedemann, G. Text Mining for Discourse Analysis: An Exemplary Study of the Debate on Minimum Wages in Germany. In Quantifying Approaches to Discourse for Social Scientists; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 183–212. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, M.J.; Spirling, A. Text Preprocessing For Unsupervised Learning: Why It Matters, When It Misleads, And What to Do About It. Political Anal. 2017, 26, 168–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V.; Lloyd-Yemoh, E. Stemming and Lemmatization: A Stemming and Lemmatization: A Comparison of Retrieval Performances. In Proceedings of the SCEI Seoul Conferences, Seoul, Korea, 10–11 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, M.B.; Grimmer, J. Text as Data: The Promise and Pitfalls of Automatic Content Analysis Methods for Political Texts. Political Anal. 2013, 21, 267–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bakarov, A. A Survey of Word Embeddings Evaluation Methods. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.09536. [Google Scholar]

- Lieven, T. How to create reproducible brand personality scales. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 24, 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenacre, M.J. Correspondence Analysis in Practice, 3rd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lehto, X.Y. Projected and Perceived Destination Brand Personalities: The Case of South Korea. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Guido, G. Brand personality: How to make the metaphor fit? J. Econ. Psychol. 2001, 22, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heritage Committee. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Update July 2019, WHC. 08/01. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2259 (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Kim, H.; Oh, C.O.; Lee, S.; Lee, S. Assessing the Economic Values of World Heritage Sites and the Effects of Perceived Authenticity on Their Values. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Zhang, H.; Mao, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y. How Outstanding Universal Value, Service Quality and Place Attachment Influences Tourist Intention Towards World Heritage Conservation: A Case Study of Mount Sanqingshan National Park, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| World Heritage Customised Personality Dictionary | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPETENCE | EXCITEMENT | SINCERITY | RUGGEDNESS | SOPHISTICATION | |||||

| Freq | Freq | Freq | Freq | Freq | |||||

| top | 297 | well-preserved | 952 | nice | 517 | complex | 106 | beautiful | 1479 |

| special | 220 | amazing | 774 | ancient | 182 | hard | 60 | stunning | 352 |

| huge | 168 | impressive | 504 | happy | 162 | difficult | 47 | picturesque | 288 |

| able | 113 | unique | 291 | typical | 156 | massive | 41 | magnificent | 221 |

| complete | 73 | modern | 231 | real | 111 | intricate | 36 | spectacular | 198 |

| perfect | 73 | free | 216 | local | 103 | western | 26 | famous | 178 |

| outstanding | 70 | fantastic | 183 | original | 102 | sunset | 25 | easy | 166 |

| rich | 52 | incredible | 122 | major | 69 | powerful | 15 | fine | 161 |

| holy | 48 | breathtaking | 121 | remarkable | 59 | terrible | 12 | excellent | 160 |

| extraordinary | 45 | awesome | 98 | worthy | 55 | uneven | 11 | fascinating | 125 |

| industrial | 38 | awe-inspiring | 81 | live | 44 | external | 10 | royal | 114 |

| fortified | 35 | absolute | 54 | limited | 43 | outdoor | 10 | pretty | 108 |

| exceptional | 31 | cool | 52 | glad | 42 | wild | 9 | gorgeous | 87 |

| worthwhile | 30 | peaceful | 51 | significant | 40 | outer | 8 | fabulous | 85 |

| golden | 29 | artistic | 36 | pleasant | 39 | challenging | 7 | grand | 67 |

| modernist | 29 | popular | 35 | accessible | 37 | rude | 7 | magical | 62 |

| favourite | 25 | particular | 32 | natural | 35 | charming | 55 | ||

| official | 25 | brilliant | 31 | helpful | 34 | quiet | 53 | ||

| knowledgeable | 23 | aware | 25 | lucky | 34 | expensive | 48 | ||

| protected | 20 | unbelievable | 25 | clean | 33 | superb | 47 | ||

| commercial | 17 | marvelous | 24 | poor | 32 | majestic | 43 | ||

| definite | 16 | unfinished | 24 | straight | 32 | enjoyable | 33 | ||

| spiritual | 16 | alive | 20 | romantic | 30 | intact | 31 | ||

| classical | 15 | colorful | 19 | sheer | 26 | astonishing | 30 | ||

| fortunate | 15 | unexpected | 19 | urban | 26 | impressed | 30 | ||

| glorious | 15 | strange | 18 | sad | 24 | splendid | 29 | ||

| reasonable | 15 | exciting | 17 | sunny | 24 | ornate | 28 | ||

| professional | 14 | incomplete | 17 | friendly | 21 | attractive | 27 | ||

| proud | 14 | recent | 17 | actual | 20 | delightful | 27 | ||

| safe | 13 | overwhelming | 15 | civil | 20 | scenic | 27 | ||

| educational | 12 | individual | 14 | single | 20 | elegant | 24 | ||

| notable | 11 | separate | 14 | simple | 19 | extensive | 23 | ||

| suitable | 11 | astounding | 13 | standard | 18 | renowned | 23 | ||

| smart | 9 | current | 13 | essential | 17 | exquisite | 22 | ||

| wealthy | 9 | intriguing | 13 | positive | 17 | enchanting | 19 | ||

| sufficient | 8 | terrific | 13 | traditional | 17 | cute | 17 | ||

| technical | 8 | excited | 12 | warm | 17 | plain | 14 | ||

| adequate | 7 | specific | 12 | comfortable | 16 | magic | 13 | ||

| atmospheric | 7 | vibrant | 12 | common | 16 | calm | 12 | ||

| dominant | 7 | creative | 11 | decent | 16 | delicious | 12 | ||

| solid | 7 | minor | 11 | inspired | 16 | gilded | 12 | ||

| strong | 7 | colourful | 10 | international | 14 | overwhelmed | 11 | ||

| untouched | 7 | fresh | 10 | deep | 13 | careful | 10 | ||

| contemporary | 9 | normal | 13 | female | 10 | ||||

| rare | 9 | proper | 13 | photogenic | 10 | ||||

| serene | 9 | sacred | 13 | opulent | 9 | ||||

| active | 8 | concrete | 10 | precious | 9 | ||||

| crazy | 8 | convenient | 10 | lavish | 8 | ||||

| relaxed | 8 | modest | 10 | celebrated | 7 | ||||

| ongoing | 6 | pure | 9 | regular | 7 | ||||

| unfriendly | 6 | regional | 9 | delicate | 6 | ||||

| authentic | 8 | soft | 6 | ||||||

| ordinary | 8 | ||||||||

| correct | 7 | ||||||||

| legendary | 7 | ||||||||

| passionate | 7 | ||||||||

| serious | 7 | ||||||||

| honest | 6 | ||||||||

| prime | 6 | ||||||||

| useful | 6 | ||||||||

| Sum of Keyword Occurrences: (13,619) in 5579 Visitor Post-experience Reviews on TripAdvisor | |||||||||

| 1704 | 4325 | 2517 | 430 | 4643 | |||||

| Keywords % to Total 222-item Scale of WH Personality | |||||||||

| 19.4 | 23.4 | 23 | 7.2 | 27.02 | |||||

| 5579 Reviews Text Frequencies: 324,034 After Text Pre-processing: Numbers, Punctuations, Stop Words Eraser | |||||||||

| Principle Coordinate (Rows) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Heritage Sites | Dimension 1 | Dimension 2 | ||

| Coord | Corr | Coord | Corr | |

| F 1 Carcassonne | 0.151 | 0.325 | −0.196 | 0.544 |

| F 2 Pont du Gard | −0.130 | 0.327 | 0.144 | 0.398 |

| F 3 Notre-Dame | 0.338 | 0.502 | 0.203 | 0.181 |

| F 4 Versailles | 0.310 | 0.851 | −0.102 | 0.092 |

| F 5 Chartres Cathedral | 0.544 | 0.682 | −0.246 | 0.139 |

| F 6 Place Stanislas | 0.468 | 0.549 | −0.423 | 0.447 |

| F 7 Historic Site of Lyon | −0.201 | 0.165 | 0.056 | 0.013 |

| F 8 Decorated Cave | −0.744 | 0.708 | 0.009 | 0.000 |

| F 9 Abbey of Fontenay | −0.047 | 0.009 | 0.141 | 0.081 |

| F 10 Strasbourg | −0.173 | 0.082 | −0.014 | 0.001 |

| G 1 Cologne Cathedral | 0.336 | 0.517 | −0.162 | 0.121 |

| G 2 Würzburg Residence | 0.317 | 0.807 | −0.116 | 0.108 |

| G 3 Museum Island | 0.080 | 0.013 | 0.698 | 0.973 |

| G 4 Town of Bamberg | −0.508 | 0.997 | −0.017 | 0.001 |

| G 5 Aachen Cathedral | 0.268 | 0.180 | −0.144 | 0.052 |

| G 6 Regensburg | −0.264 | 0.453 | 0.140 | 0.127 |

| G 7 Zollverein | 0.452 | 0.610 | 0.279 | 0.233 |

| G 8 Speicherstadt | 0.452 | 0.610 | 0.279 | 0.233 |

| G 9 Quedlinburg | −0.274 | 0.425 | −0.145 | 0.119 |

| G 10 Speyer Cathedral | 0.095 | 0.050 | 0.073 | 0.030 |

| IT 1 Trulli Alberobello | −0.369 | 0.945 | −0.061 | 0.026 |

| IT 2 Pompei | −0.162 | 0.248 | 0.178 | 0.302 |

| 1T 3 Centre Rome | −0.307 | 0.963 | 0.005 | 0.000 |

| IT 4 Sassi | 0.025 | 0.037 | −0.039 | 0.094 |

| IT 5 Agrigento | −0.012 | 0.003 | 0.051 | 0.056 |

| IT 6 Villa Casale | 0.056 | 0.251 | 0.046 | 0.164 |

| IT 7 Villa Tivoli | 0.021 | 0.009 | −0.165 | 0.533 |

| IT 8 San Gimignano | −0.442 | 0.959 | 0.076 | 0.028 |

| IT 9 Val d’Orcia | −0.510 | 0.419 | −0.060 | 0.006 |

| IT 10 Centre Florence | 0.007 | 0.000 | −0.468 | 0.312 |

| SP 1 Alhambra | 0.262 | 0.589 | 0.207 | 0.367 |

| SP 2 Cathedral, Alcázar | 0.260 | 0.810 | 0.015 | 0.003 |

| SP 3 Centre Cordoba | 0.211 | 0.860 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| SP 4 Antoni Gaudí Works | 0.164 | 0.159 | −0.336 | 0.665 |

| SP 5 Palace catalan Music | 0.237 | 0.293 | −0.310 | 0.502 |

| SP 6 Recinte Modernista | 0.427 | 0.653 | 0.211 | 0.160 |

| SP 7 La Lonja | 0.177 | 0.220 | −0.152 | 0.163 |

| SP 8 Burgos Cathedral | 0.454 | 0.831 | 0.122 | 0.060 |

| SP 9 Vizcaya Bridge | −0.040 | 0.009 | −0.138 | 0.107 |

| SP 10 Escurial | 0.116 | 0.060 | 0.387 | 0.667 |

| Active Total | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassan, M.A.E.; Zerva, K.; Aulet, S. Brand Personality Traits of World Heritage Sites: Text Mining Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116142

Hassan MAE, Zerva K, Aulet S. Brand Personality Traits of World Heritage Sites: Text Mining Approach. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116142

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Mohamed Abdalla Elsayed, Konstantina Zerva, and Silvia Aulet. 2021. "Brand Personality Traits of World Heritage Sites: Text Mining Approach" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116142

APA StyleHassan, M. A. E., Zerva, K., & Aulet, S. (2021). Brand Personality Traits of World Heritage Sites: Text Mining Approach. Sustainability, 13(11), 6142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116142