The Effects of Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Orientation on Crowdfunding Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Crowdfunding and Sustainability

2.2. Framing and Frames in Social Movement Theory

2.2.1. Meaning Construction in Social Movements

2.2.2. Framing and Sustainable Consumption

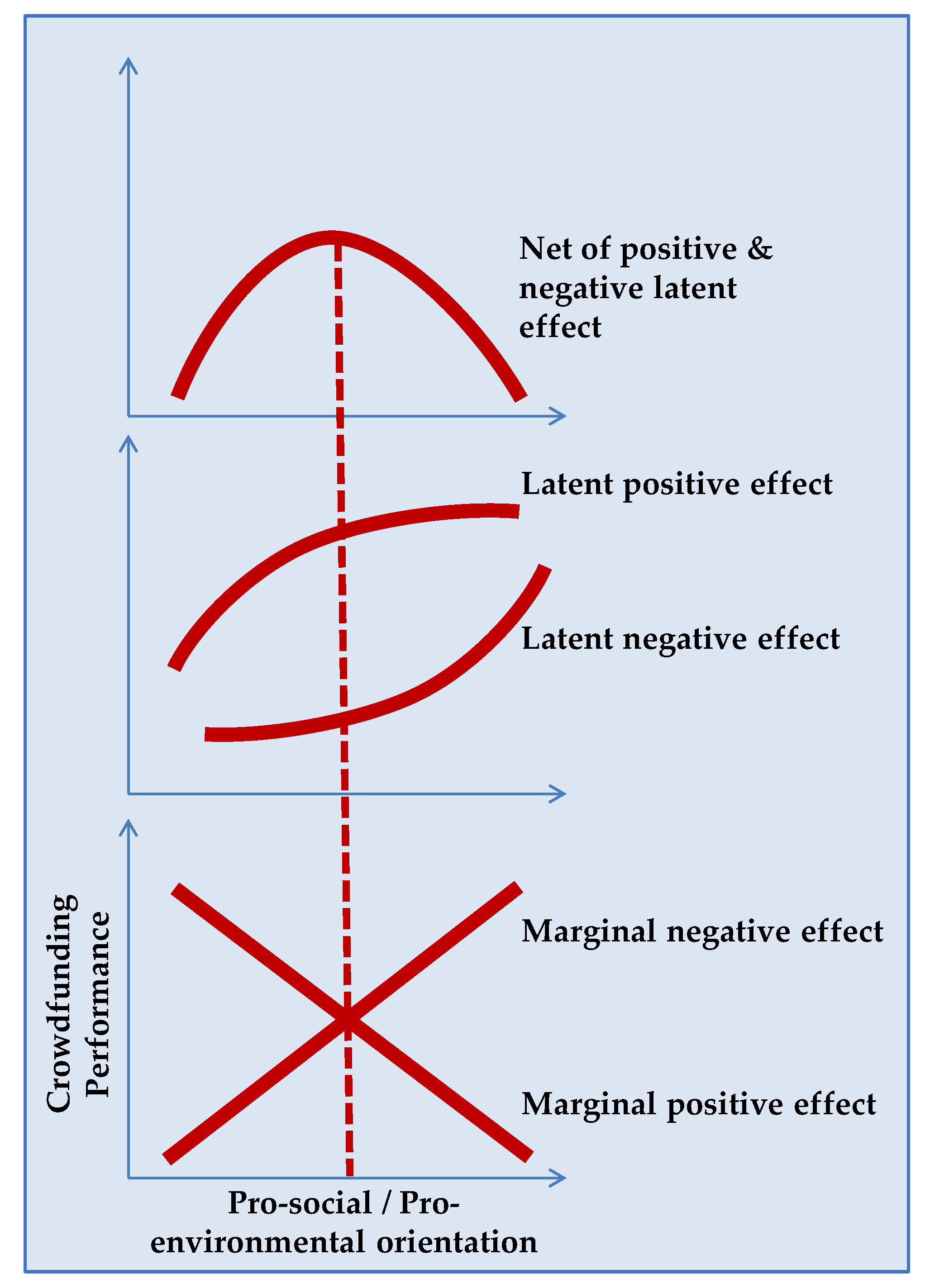

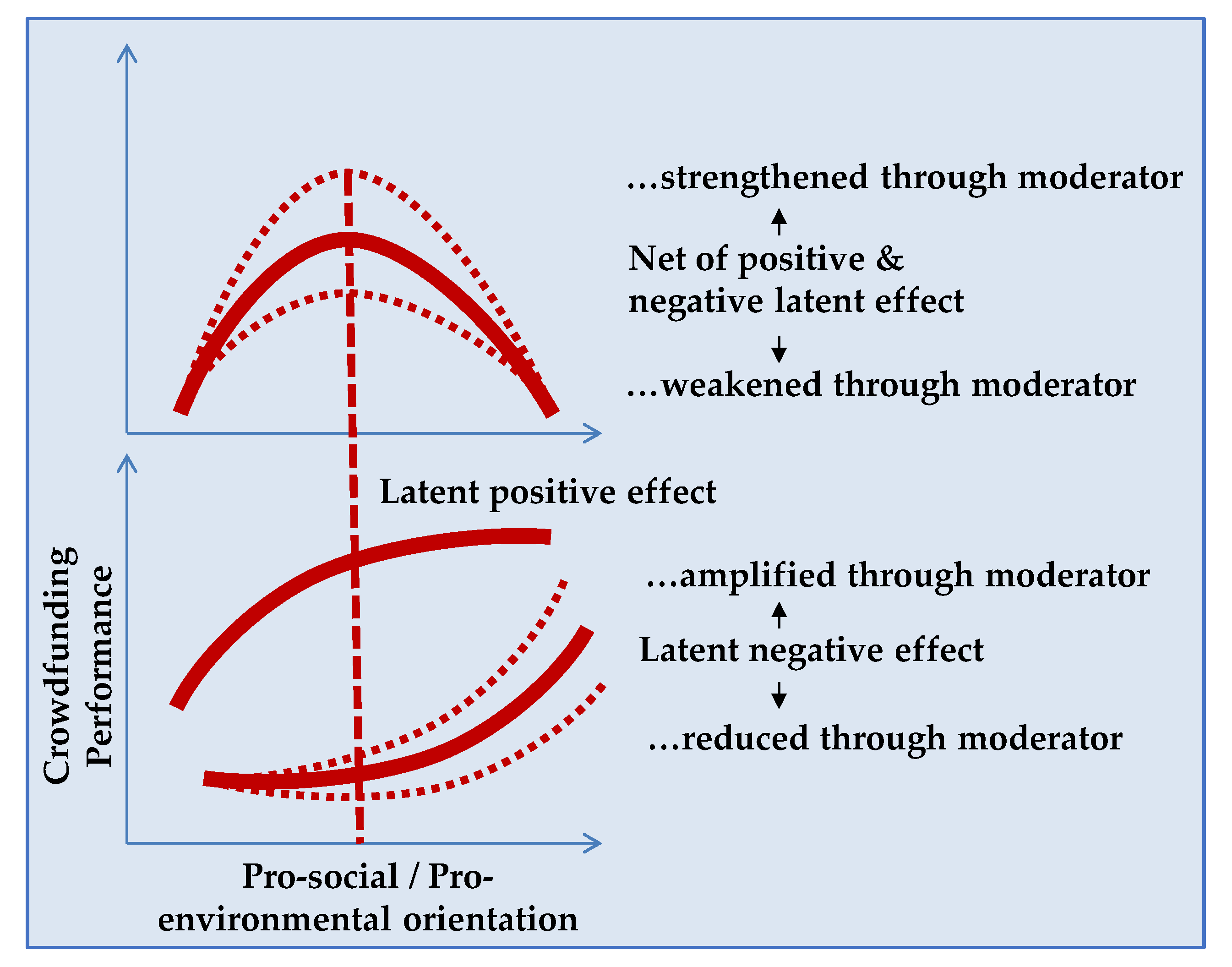

2.3. Research Hypotheses: Emphasis of Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Framing on Crowdfunding Performance and the Role of Creativity

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Dependent Variables

3.3. Independent Variables and Model Estimation Procedures

3.4. Moderating Variable

3.5. Control Variables

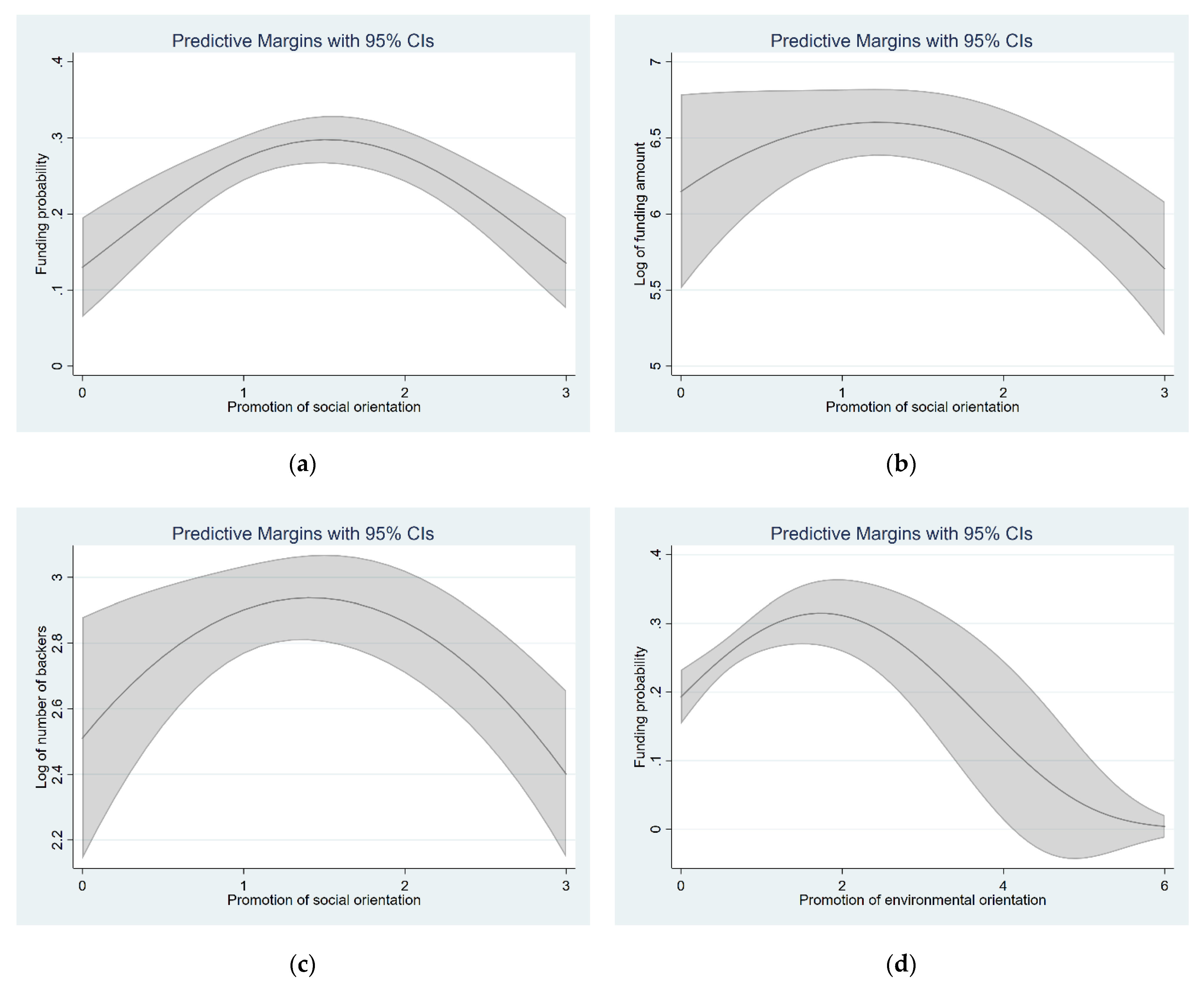

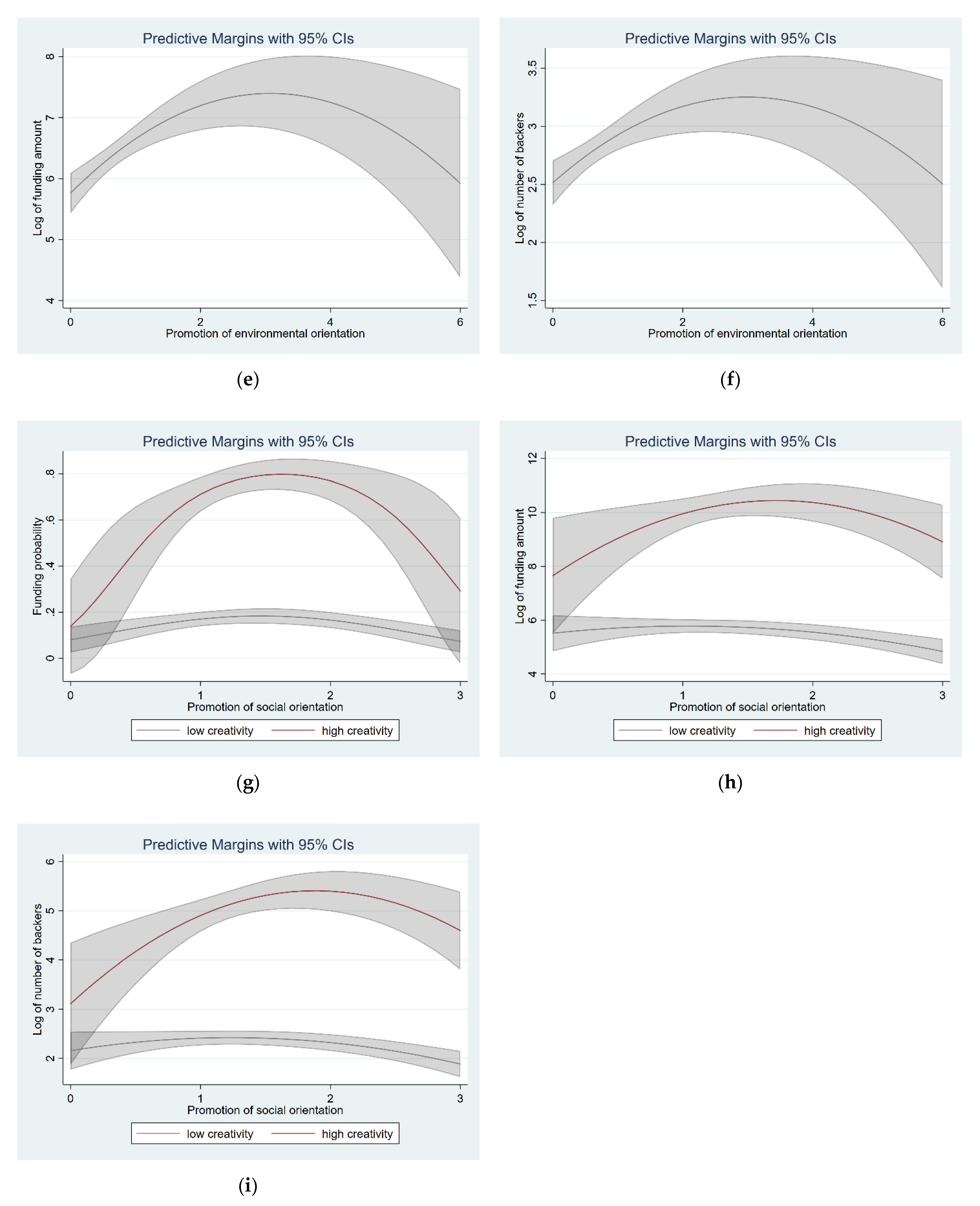

4. Empirical Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cumming, D.J.; Leboeuf, G.; Schwienbacher, A. Crowdfunding models: Keep-it-all vs. all-or-nothing. Financ. Manag. 2015, 49, 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assenova, V.; Best, J.; Cagney, M.; Ellenoff, D.; Karas, K.; Moon, J.; Neiss, S.; Suber, R.; Sorenson, O. The present and future of crowdfunding. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholakova, M.; Clarysse, B. Does the possibility to make equity investments in crowdfunding projects crowd out reward-based investments? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwienbacher, A.; Larralde, B. Crowdfunding of small entrepreneurial ventures. In The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lehner, O.M. Crowdfunding social ventures: A model and research agenda. Ventur. Cap. 2013, 15, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, T.H.; Davis, B.C.; Short, J.C.; Webb, J.W. Crowdfunding in a prosocial microlending environment: Examining the role of intrinsic versus extrinsic cues. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2015, 39, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calic, G.; Mosakowski, E. Kicking off social entrepreneurship: How a sustainability orientation influences crowdfunding success. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 738–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, T.W.; Renko, M.; Block, E.; Meyskens, M. Funding the story of hybrid ventures: Crowdfunder lending preferences and linguistic hybridity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 643–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defazio, D.; Franzoni, C.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. How pro-social framing affects the success of crowdfunding projects: The role of emphasis and information crowdedness. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J. Crowdfunding for environmental ventures: An empirical analysis of the influence of environmental orientation on the success of crowdfunding initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickson, S.L. Organizational identity orientation: The genesis of the role of the firm and distinct forms of social value. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 864–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.R. Crowdfunding through a partial organization lens—The co-dependent organization. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.R.; Binder, J.K. I am what I pledge: The importance of value alignment for mobilizing backers in reward-based crowdfunding. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 45, 531–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenny, A.F.; Allison, T.H.; Ketchen, D.J., Jr.; Short, J.C.; Ireland, R.D. How should crowdfunding research evolve? A survey of the entrepreneurship theory and practice editorial board. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenny, A.F.; Short, J.C.; Newman, S.M. CAT Scanner (Version 1.0) [Software]. 2012. Available online: http://www.catscanner.net/ (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Moritz, A.; Block, J.H. Crowdfunding: A literature review and research directions. In Crowdfunding in Europe; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fisk, R.P.; Patrício, L.; Ordanini, A.; Miceli, L.; Pizzetti, M.; Parasuraman, A. Crowd-funding: Transforming customers into investors through innovative service platforms. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 443–470. [Google Scholar]

- Galak, J.; Small, D.; Stephen, A.T. Microfinance decision making: A field study of prosocial lending. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, S130–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F. Social Entrepreneurship Domain: Setting Boundaries; Edward Elger Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.; Ng, A. Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlin, J.R.; Luchs, M.G.; Phipps, M. Consumer perceptions of the social vs. environmental dimensions of sustainability. J. Consum. Policy 2017, 40, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.L.; Jennings, J.E.; Jennings, P.D. Do the stories they tell get them the money they need? The role of entrepreneurial narratives in resource acquisition. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1107–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwittay, A. Digital mediations of everyday humanitarianism: The case of Kiva.org. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 1921–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E. The dynamics of crowdfunding: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frydrych, D.; Bock, A.J.; Kinder, T. Creating project legitimacy-the role of entrepreneurial narrative in reward-based crowdfunding. In International Perspectives on Crowdfunding: Positive, Normative and Critical Theory; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016; pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen, J.P.; Werner, M.D. Putting framing in perspective: A review of framing and frame analysis across the management and organizational literature. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 181–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. Framing contests: Strategy making under uncertainty. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, D.A. Framing processes, ideology, and discursive fields. In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 380–412. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, D.A.; Benford, R.D. Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. Int. Soc. Mov. Res. 1988, 1, 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Benford, R.D.; Snow, D.A. Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 611–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, D.A. Elaborating the discursive contexts of framing: Discursive fields and spaces. Stud. Symb. Interact. 2008, 30, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.A.; Benford, R.D.; Snow, D.A. Identity fields: Framing processes and the social construction of movement identities. In New Social Movements: From Ideology to Identity; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994; Volume 185, p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, D.A.; Rochford, E.B., Jr.; Worden, S.K.; Benford, R.D. Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1986, 51, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition; Mcgraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, S. The mind and heart of resonance: The role of cognition and emotions in frame effectiveness. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 711–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, S.; Weber, K. Marks of distinction: Framing and audience appreciation in the context of investment advice. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015, 60, 333–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, J.; Ocasio, W.; Jones, C. Vocabularies and vocabulary structure: A new approach linking categories, practices, and institutions. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 41–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benford, R.D. “You could be the hundredth monkey”: Collective action frames and vocabularies of motive within the nuclear disarmament movement. Soc. Q. 1993, 34, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.; Bejarano, T.A. Convincing the crowd: Entrepreneurial storytelling in crowdfunding campaigns. Strateg. Organ. 2017, 15, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Crowdfunding technological innovations: Interaction between consumer benefits and rewards. Technovation 2019, 84, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismara, S. Sustainability in equity crowdfunding. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 141, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, T. Sounds novel or familiar? Entrepreneurs’ framing strategy in the venture capital market. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 105930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagazio, C.; Querci, F. Exploring the multi-sided nature of crowdfunding campaign success. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O. Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S. “I need you too!” Corporate identity attractiveness for consumers and the role of social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 71, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green claims and message frames: How green new products change brand attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. The Ethical Consumer; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, W.L. The personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2012, 644, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotte, J.; Trudel, R. Socially Conscious Consumerism: A Systematic Review of the Body of Knowledge. 2009. Available online: https://www.nbs.net/articles/systematic-review-socially-conscious-consumerism?rq=cotte (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- White, K.; MacDonnell, R.; Ellard, J.H. Belief in a just world: Consumer intentions and behaviors toward ethical products. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheletti, M. Why political consumerism? In Political Virtue and Shopping; Springer: Berling, Germany, 2003; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of environmentally and socially responsible sustainable consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.A.; Murray, D.L. Ethical consumption, values convergence/divergence and community development. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 26, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hertog, J.K.; McLeod, D.M. A multiperspectival approach to framing analysis: A field guide. In Framing Public Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Parhankangas, A.; Ehrlich, M. How entrepreneurs seduce business angels: An impression management approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.H.; Buffart, M.; Croidieu, G. TMI: Signaling credible claims in crowdfunding campaign narratives. Group Organ. Manag. 2016, 41, 717–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friestad, M.; Wright, P. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, I.P.; Schneider, S.L.; Gaeth, G.J. All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1998, 76, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K. Attitudes Toward History; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.J. A model of multiattribute judgments under attribute uncertainty and informational constraint. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivetz, R.; Simonson, I. The effects of incomplete information on consumer choice. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.N. Morality and the Market: Consumer Pressure for Corporate Accountability; Routledge: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M. Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M.; Louviere, J.J.; Burke, P.F. Do social product features have value to consumers? Int. J. Res. Mark. 2008, 25, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A. Unpacking the ethical product. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 30, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretschneider, U.; Leimeister, J.M. Not just an ego-trip: Exploring backers’ motivation for funding in incentive-based crowdfunding. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiadou, E.; Huijben, J.; Raven, R. Three is a crowd? Exploring the potential of crowdfunding for renewable energy in The Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 128, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.F.; Moy, N.; Schaffner, M.; Torgler, B. The effects of money saliency and sustainability orientation on reward based crowdfunding success. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 125, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.C.; Hmieleski, K.M.; Webb, J.W.; Coombs, J.E. Funders’ positive affective reactions to entrepreneurs’ crowdfunding pitches: The influence of perceived product creativity and entrepreneurial passion. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickstarter. Kickstarter: About Us. Available online: https://www.kickstarter.com/about (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- Hennessey, B.A.; Amabile, T.M. Creativity. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Componential theory of creativity. Harv. Bus. Sch. 2012, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D.; Gustafson, S.B. Creativity syndrome: Integration, application, and innovation. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. What we know about the creative process. Front. Creat. Innov. Manag. 1985, 4, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ucbasaran, D.; Westhead, P.; Wright, M. The extent and nature of opportunity identification by experienced entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Cardozo, R. Sensitivity and creativity in entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: A framework for empirical investigation. In Proceedings of the Sixth Global Entrepreneurship Research Conference, Imperial College, London, UK, 1 June 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Carroll, A.B. Integrating and unifying competing and complementary frameworks: The search for a common core in the business and society field. Bus. Soc. 2008, 47, 148–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Preuss, L.; Pinkse, J.; Figge, F. Cognitive frames in corporate sustainability: Managerial sensemaking with paradoxical and business case frames. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 463–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Thinking of the organization as a system: The role of managerial perceptions in developing a corporate social responsibility strategic agenda. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. Off. J. Int. Fed. Syst. Res. 2008, 25, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, B. The New Sustainability Advantage: Seven Business Case Benefits of a Triple Bottom Line; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Held, M. Sustainable development from a temporal perspective. Time Soc. 2001, 10, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawinski, N.; Bansal, P. A matter of time: The temporal perspectives of organizational responses to climate change. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 1537–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garud, R.; Schildt, H.A.; Lant, T.K. Entrepreneurial storytelling, future expectations, and the paradox of legitimacy. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheaf, D.J.; Davis, B.C.; Webb, J.W.; Coombs, J.E.; Borns, J.; Holloway, G. Signals’ flexibility and interaction with visual cues: Insights from crowdfunding. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 720–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickstarter. Kickstarter Creator Handbook: Funding. Available online: https://www.kickstarter.com/help/handbook/funding (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Parhankangas, A.; Renko, M. Linguistic style and crowdfunding success among social and commercial entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, A.H.; Wolfe, M.T.; Short, J.C.; McKenny, A.F.; Pidduck, R.J. Narcissistic rhetoric and crowdfunding performance: A social role theory perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 780–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, W.G.; Basu, A.; Mullahy, J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J. Health Econ. 2005, 24, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, R.; Poor, N. Factors for success in repeat crowdfunding: Why sugar daddies are only good for Bar-Mitzvahs. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirnevskiy, V.; Bendig, D.; Brettel, M. The influence of internal social capital on serial creators’ success in crowdfunding. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; McKenny, A.F.; Reid, S.W. More than words? Computer-aided text analysis in organizational behavior and psychology research. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencle, N.; Mălăescu, I. What’s in the words? Development and validation of a multidimensional dictionary for CSR and application using prospectuses. J. Emerg. Technol. Account. 2016, 13, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenny, A.F.; Aguinis, H.; Short, J.C.; Anglin, A.H. What doesn’t get measured does exist: Improving the accuracy of computer-aided text analysis. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2909–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott-Allen, R. The Wellbeing of Nations; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein, J.; Mueller, J. Implicit theories of creative ideas: How culture guides creativity assessments. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2016, 2, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Catalini, C.; Goldfarb, A. Crowdfunding: Geography, social networks, and the timing of investment decisions. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2015, 24, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Catalini, C.; Goldfarb, A. Some simple economics of crowdfunding. Innov. Policy Econ. 2014, 14, 63–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson, P.; Delmar, F.; Wiklund, J. Entrepreneurship as growth; growth as entrepreneurship. Entrep. Growth Firms 2006, 1, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hakenes, H.; Schlegel, F. Exploiting the Financial Wisdom of the Crowd-Crowdfunding as a Tool to Aggregate Vague Information. 2014. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2475025 (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Cordova, A.; Dolci, J.; Gianfrate, G. The determinants of crowdfunding success: Evidence from technology projects. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 181, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marom, D.; Robb, A.; Sade, O. Gender Dynamics in Crowdfunding (Kickstarter): Evidence on Entrepreneurs, Investors, Deals and Taste-Based Discrimination. 2016. Available online: https://www.consob.it/documents/46180/46181/c27022015-dan-marom.pdf/66c9c41d-0404-438a-b8a5-72949318836e (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Greenberg, J.; Mollick, E. Leaning in or leaning on? Gender, homophily, and activism in crowdfunding. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, G.; Guerini, M.; Lamastra, C.R. Why crowdfunding projects can succeed: The role of proponents’ individual and territorial social capital. Inf. Syst. Behav. Soc. Methods 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Li, D.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y. The role of multidimensional social capital in crowdfunding: A comparative study in China and US. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P. A Guide to Econometrics; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleflamme, P.; Lambert, T.; Schwienbacher, A. Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Pierrakis, Y. The Venture Crowd: Crowdfunding Equity Investments into Business; Nesta: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

| Social Elements | Dictionary Examples | CATA Dictionary |

|---|---|---|

| Health and population | “health benefits” “employee wellbeing” “benefit the masses.” | Employee Employee Social and community |

| Wealth (e.g., household wealth) | “employee welfare” “affordable housing” | Employee Social and community |

| Knowledge and culture | “human development” “cultural preservation” “educational programs” | Human rights Social and community Employee |

| Community (e.g., freedom) | “community projects” “civic engagement” “inclusiveness” | Social and community Social and community Human rights |

| Equity (e.g., gender equity) | “gender diversity” “employee equity” | Human rights Employee |

| Environment Elements | Dictionary Examples | CATA Dictionary |

|---|---|---|

| Land | “land conservation” “rainforest” | Environment Environment |

| Water | “groundwater” “water purification” | Environment Environment |

| Air | “ozone depletion” “emissions” | Environment Environment |

| Species and genes (e.g., wild/domesticated diversity) | “caged animal” “genetically modified” | Environment Environment |

| Resource use | “renewable energies” “energy efficiency” | Environment Environment |

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: | |||||

| Successfully funded | 1049 | 0.255 | 0.436 | 0 | 1 |

| Log of amount pledged | 1049 | 6.39 | 3.743 | 0 | 14.96 |

| Log of number of backers | 1049 | 2.802 | 2.204 | 0 | 9.156 |

| Independent variable: | |||||

| SO social | 1049 | 1.488 | 0.794 | 0 | 5.935 |

| SO environment | 1049 | 0.823 | 0.864 | 0 | 9.737 |

| Moderator variable: | |||||

| Creativity | 1049 | 0.186 | 0.389 | 0 | 1 |

| Control variables: | |||||

| Duration | 1049 | 37.182 | 12.417 | 7 | 60.042 |

| Prototype gallery | 1049 | 0.321 | 0.467 | 0 | 1 |

| Log of goal | 1049 | 10.088 | 1.111 | 8.517 | 15.425 |

| Gender (1 = male) | 1049 | 0.827 | 0.378 | 0 | 1 |

| 1049 | 0.315 | 0.465 | 0 | 1 |

| Variables | VIF | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 SO social | 1.04 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 2 SO environment | 1.04 | −0.029 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 3 Creativity | 1.02 | −0.037 | 0.064 | 1.000 | |||||

| 4 Duration | 1.02 | 0.027 | −0.033 | −0.035 | 1.000 | ||||

| 5 Prototype gallery | 1.02 | −0.001 | 0.010 | −0.072 | −0.062 | 1.000 | |||

| 6 Log of goal | 1.01 | −0.016 | −0.016 | 0.017 | 0.111 | 0.022 | 1.000 | ||

| 7 Gender | 1.01 | −0.076 | 0.015 | −0.015 | −0.015 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 1.000 | |

| 8 Facebook | 1.01 | −0.025 | −0.031 | −0.076 | −0.035 | 0.176 | −0.021 | 0.021 | 1.000 |

| Dependent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successfully Funded | ||||

| Independent variables | ||||

| SO social | 1.920108 *** (0.5152531) | |||

| SO social squared | −0.6327851 *** (0.1572913) | |||

| SO environment | 1.06648 *** | |||

| (0.3054654) | ||||

| SO environment squared | −0.3073523 *** | |||

| (0.0984528) | ||||

| Moderator variable | ||||

| Creativity | 2.681317 *** | 2.714216 *** | ||

| (0.2018984) | (0.2006221) | |||

| Moderator terms | ||||

| SO social × creativity | 2.945252 ** | |||

| (1.350475) | ||||

| SO social squared × creativity | −0.8581894 ** | |||

| (0.4162497) | ||||

| SO environment × creativity | −0.1348543 | |||

| (0.7506852) | ||||

| SO environment squared × creativity | −0.0924645 | |||

| (0.2187173) | ||||

| Control variables | ||||

| Duration | −0.0215298 *** (0.0075455) | −0.0200979 *** (0.007478) | −0.0227254 *** (0.0076291) | −0.0203139 *** (0.0074956) |

| Prototype gallery | −0.4728156 ** (0.1967667) | −0.4508344 ** (0.1956723) | −0.4779293 ** (0.1979541) | −0.4491765 ** (0.1962095) |

| Log of goal | −0.4165938 *** (0.0881734) | −0.3905198 *** (0.0873755) | −0.4318566 ** (0.0890654) | −0.3935945 *** (0.0878419) |

| Gender | −0.4810685 ** (0.2184813) | −0.4037996 * (0.2160087) | −0.4640738 ** (0.2206158) | −0.4089235 * (0.216492) |

| −0.8657768 *** (0.2075535) | −0.8496694 *** (0.2075708) | −0.8793573 *** (0.2091075) | −0.8501866 *** (0.208364) | |

| Constant | 2.800309 *** (0.9624383) | 3.056915 *** (0.9161699) | 3.366041 *** (0.9890082) | 3.06701 *** (0.9256092) |

| Dependent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log of Amount Pledged | ||||

| Independent variables | ||||

| SO social | 0.7457309 ** | |||

| (0.3679957) | ||||

| SO social squared | −0.3049152 *** | |||

| (0.0944174) | ||||

| SO environment | 1.063266 *** | |||

| (0.2247755) | ||||

| SO environment squared | −0.1727496 *** | |||

| (0.0431899) | ||||

| Moderator variable | ||||

| Creativity | 4.255518 *** | 4.225161 *** | ||

| (0.260996) | (0.260864) | |||

| Moderator terms | ||||

| SO social × creativity | 2.735261 ** | |||

| (1.307635) | ||||

| SO social squared × creativity | −0.6964062 ** | |||

| (0.337918) | ||||

| SO environment × creativity | −0.0678463 | |||

| (0.8379682) | ||||

| SO environment squared × creativity | −0.1613315 | |||

| (0.2049396) | ||||

| Control variables | ||||

| Duration | −0.0274385 *** | −0.0267372 *** | −0.0283448 *** | −0.0269792 *** |

| 0.00817 | (0.0081612) | (0.0081794) | (0.0081526) | |

| Prototype gallery | 0.2399189 *** (0.2194481) | 0.1981808 (0.2192495) | 0.2400757 (0.2192489) | 0.2031352 (0.2189864) |

| Log of goal | −0.0099292 (0.0911028) | −0.0046803 (0.0909419) | −0.013252 (0.0910641) | −0.0021553 (0.0908525) |

| Gender | −0.6468451 ** (0.266842) | −0.5791563 ** (0.26579) | −0.6180949 ** (0.2669714) | −0.5712505 ** (0.2655197) |

| −0.8315246 *** (0.2203278) | −0.760119 *** (0.2202037) | −0.8060118 *** (0.2204484) | −0.7596774 *** (0.219991) | |

| Constant | 7.196154 *** (1.028003) | 6.671469 *** (0.9817988) | 7.408725 *** (1.035376) | 6.565392 *** (0.9819324) |

| Dependent Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log of Number of Backers | ||||

| Independent variables | ||||

| SO social | 0.6048428 *** | |||

| (0.212296) | ||||

| SO social squared | −0.2137361 *** | |||

| (0.0544681) | ||||

| SO environment | 0.4935246 *** | |||

| (0.1303064) | ||||

| SO environment squared | −0.0825476 *** | |||

| (0.0250379) | ||||

| Moderator variable | ||||

| Creativity | 2.588772 *** | 2.594346 *** | ||

| (0.150565) | (0.1512275) | |||

| Moderator terms | ||||

| SO social × creativity | 2.012044 *** | |||

| (0.753347) | ||||

| SO social squared × creativity | −0.4753748 ** | |||

| (0.1946794) | ||||

| SO environment × creativity | −0.3457735 | |||

| (0.4847662) | ||||

| SO environment squared × creativity | −0.06032 | |||

| (0.1185579) | ||||

| Control variables | ||||

| Duration | −0.0155218 *** (0.0047137) | −0.0152653 *** (0.0047312) | −0.0162861 *** (0.0047123) | −0.0154043 *** (0.0047163) |

| Prototype gallery | −0.1036755 (0.1265966) | −0.1225682 (0.1271028) | −0.1018288 (0.1263124) | −0.1194491 (0.126684) |

| Log of goal | −0.046894 (0.052556) | −0.0452441 (0.0527206) | −0.0503654 (0.0524633) | −0.0439533 (0.0525584) |

| Gender | −0.4658385 *** (0.1539374) | −0.4379344 *** (.1540831) | −0.4428025 *** (0.153806) | −0.4335456 *** (0.1536037) |

| −0.6010039 *** (0.127104) | −0.5679778 *** (0.127656) | −0.5842465 *** (0.1270035) | −0.5656264 *** (0.1272652) | |

| Constant | 3.686854 *** (0.5930407) | 3.63598 *** (0.5691662) | 3.86932 *** (0.596495) | 3.545521 *** (0.5680498) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Selasinsky, C.; Lutz, E. The Effects of Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Orientation on Crowdfunding Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116064

von Selasinsky C, Lutz E. The Effects of Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Orientation on Crowdfunding Performance. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):6064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116064

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Selasinsky, Constantin, and Eva Lutz. 2021. "The Effects of Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Orientation on Crowdfunding Performance" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 6064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116064

APA Stylevon Selasinsky, C., & Lutz, E. (2021). The Effects of Pro-Social and Pro-Environmental Orientation on Crowdfunding Performance. Sustainability, 13(11), 6064. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116064