Entrepreneurs Traits/Characteristics and Innovation Performance of Waste Recycling Start-Ups in Ghana: An Application of the Upper Echelons Theory among SEED Award Winners

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptional Framework

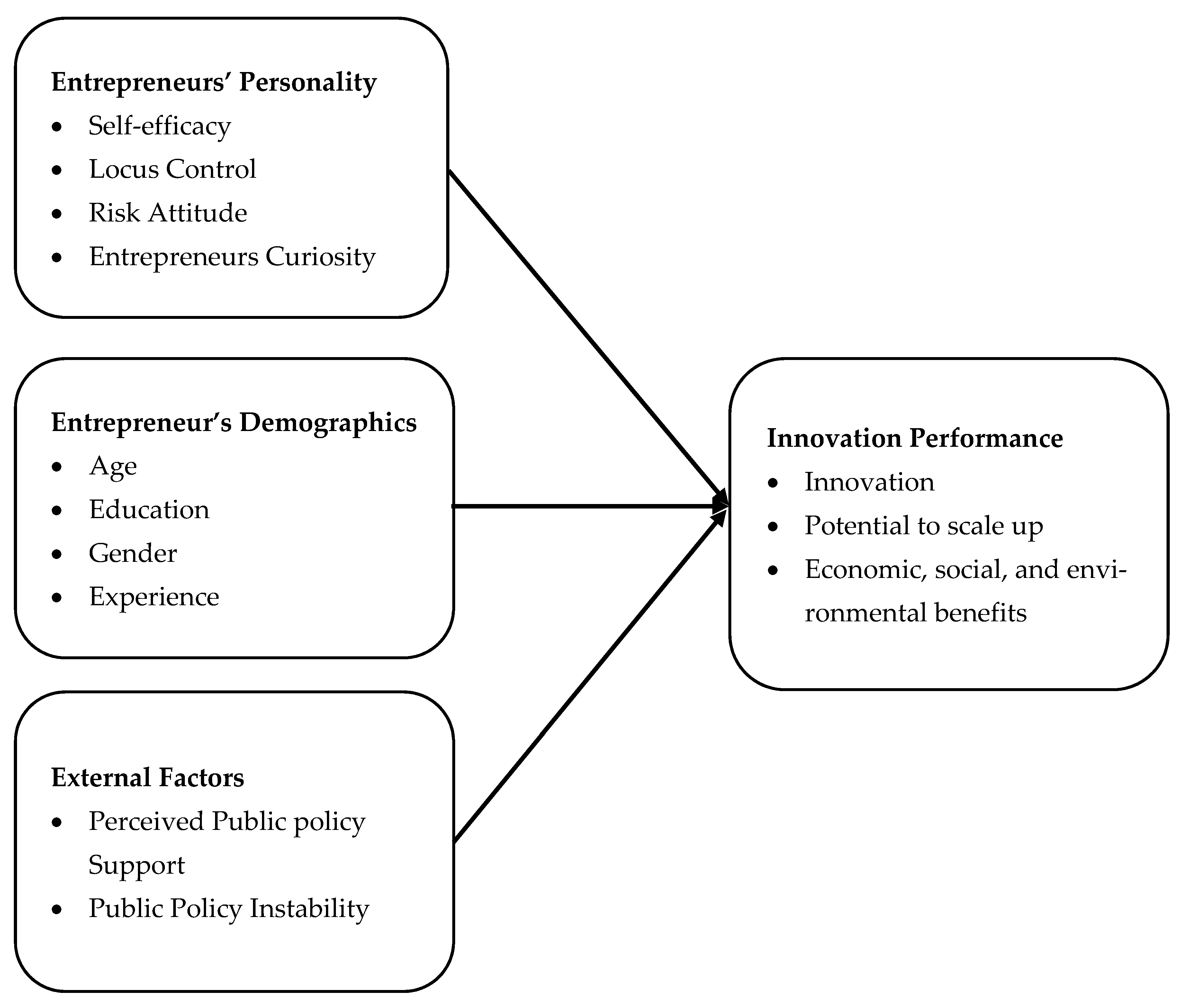

2.1. Conceptional Framework

2.2. Entrepreneurs’ Personality

2.2.1. Self-Efficacy

2.2.2. Locus of Control

2.2.3. Risk Attitude

2.2.4. Entrepreneurs’ Curiosity

2.3. Entrepreneurs’ Demographics

2.3.1. Age

2.3.2. Education

2.3.3. Gender

2.3.4. Entrepreneurs’ Experience

2.4. External Factors

3. Methodology and Measurement

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Measurement of the Constructs

3.3. Validity and Reliability

4. Empirical Study

4.1. Analysis

4.2. Regression Analysis

4.2.1. Regression Model 1 (Control Variables)

4.2.2. Regression Model 2 (Control Variables and all Independent Variables)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kyere, R.; Addaney, M. Decentralization and Solid Waste Management in Urbanizing Ghana: Moving beyond the Status Quo. In Municipal Solid Waste Management; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.H.; Fisch, C.O.; Van Praag, M. The Schumpeterian Entrepreneur: A Review of the Empirical Evidence on the Innovative Entrepreneurship Antecedents, Behavior and Consequences of innovative entrepreneurship. Ind. Innov. 2016, 24, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Award, E.; Job, W.Á. Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 1, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Mueller, S.L. A case for comparative entrepreneurship: Assessing the relevance of culture. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.W.; Liu, G.; Toren, W.; Yusoff, W.; Rosmawati, C.; Mat, C. Social Entrepreneurial Passion and Social Innovation Performance. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 12, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, Z.; Kouame, D. Assessing the impact of entrepreneurial intention on self-employment: Evidence from ghana. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2018, 4, 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Maastricht, P. Entrepreneureial Traits and Innovation: Evidence from Chile; Universitaire Pers Maastricht: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Ribeiro-soriano, D.; Schüssler, M. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) in entrepreneurship and innovation research—The rise of a method. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 14, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyver, M.J.; Lu, T.J. Sustaining Innovation Performance in SMEs: Exploring the Roles of Strategic Entrepreneurship and IT Capabilities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.L.; Bolson, C. Public policy for solid waste and the organization of waste pickers: Potentials and limitations to promote social inclusion in Brazil. Recycling 2018, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chen, S. Gender moderates firms’ innovation performance and entrepreneurs’ self-efficacy and risk propensity. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2016, 44, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protogerou, A.; Caloghirou, Y.; Vonortas, N.S. Determinants of young firms’ innovative performance: Empirical evidence from Europe. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenechea-Elberdin, M.; Sáenz, J.; Kianto, A. Exploring the role of human capital, renewal capital and entrepreneurial capital in innovation performance in high-tech and low-tech firms. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2017, 15, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibidunni, A.S.; Ibidunni, O.M.; Olokundun, A.M.; Oke, O.A.; Ayeni, A.W.; Falola, H.O.; Salau, O.P.; Borishade, T.T. Examining the moderating effect of entrepreneurs demographic characteristics on strategic entrepreneurial orientations and competitiveness of SMEs. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Quatraro, F.; Vivarelli, M. Drivers of Entrepreneurship and Post-entry Performance of Newborn Firms in Developing Countries. World Bank Res. Obs. 2015, 30, 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E. The Relationship of Personality to Entrepreneurial Intentions and Performance: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realization, S.; Success, B.; Frank, H.; Lueger, M.; Korunka, C. The Significance of Personality in Business Start-Up Intentions, The significance of personality in business start-up intentions, start-up realization and business success. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2007, 19, 227–251. [Google Scholar]

- Darnihamedani, P.; Block, J.H. Taxes, start-up costs and innovative entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 51, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, S. Which Entrepreneurial Traits are Critical in Determining Success? Otago Manag. Grad. Rev. 2016, 14, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, P.K.; William, R.K.; Tina, X. Personality Traits of Entrepreneurs: A Review of Recent Literature. Found. Trends Entrep. 2018, 14, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.; Sun, W.; Tsai, S. An Empirical Study on Entrepreneurial Orientation, Absorptive Capacity, and SMEs’ Innovation Performance: A Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal, T.Q.; Access, E.A. Smart and illicit: WHO becomes an entrepreneur and do they earn more? Q. J. Econ. 2016, 2, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yaakub, N.A.; Nor, K.M.; Jamal, N.M. Online versus offline entrepreneur Personalities: A review on entrepreneur performance. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 450–462. [Google Scholar]

- Tshetshema, C.T.; Chan, K.Y. A systematic literature review of the relationship between demographic diversity and innovation performance at team-level. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Byun, G.; Ding, F. The Direct and Indirect Impact of Gender Diversity in New Venture Teams on Innovation Performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, C.; Muñoz-pascual, L.; Galende, J. Antecedents to innovation performance in SMEs: A mixed methods. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Factors influencing innovation capability of small and medium-sized enterprises in Korean manufacturing sector: Facilitators, barriers and moderators. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2018, 76, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrekson, M.; Sanandaji, T. Small business activity does not measure entrepreneurship. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 111, 1760–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Rubinstein, Y. Smart and Illicit: Who Becomes an Entrepreneur and Does it Pay? NBER Work. Pap. 2013, 1, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golichenko, O.G. The National Innovation System. Probl. Econ. Transit. 2016, 1991, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Si, S. Government policies and firms’ entrepreneurial orientation: Strategic choice and institutional perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 93, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, B.; Kujinga, L. The institutional environment and social entrepreneurship intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 638–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, F. Defining and measuring innovation in all sectors of the economy. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, B.H., Jr.; Lovelace, J.B.; Cowen, A.P.; Hiller, N.J. Metacritiques of Upper Echelons Theory: Verdicts and Recommendations for Future Research. J. Manag. 2020, 46, 1029–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A.; Mason, P.A. Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, B.T.; van Iddekinge, C.; Haleblian, J. Do Ceos Matter to firm strategic actions and firm performance? A meta-analytic investigation based on upper echelons theory. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 775–862. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M.A.; Matz, C.; Xu, K. A current view of resource based theory in operations management: A response to Bromiley and Rau. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 41, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C. Editor’s forum upper echelons theory: An update. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, R.; Odoom, D. Examining the Institutional Arrangements Regarding Public Private Partnership in Solid Waste Management in Ghana: From the Perspective of Sunyani Municipality. Int. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Samwine, T.; Wu, P.; Xu, L.; Shen, Y.; Appiah, E.; Yaoqi, W. Challenges and Prospects of Solid Waste Management in Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Monit. Anal. 2017, 5, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olokundun, M.; Falola, H.; Ibidunni, S.; Ogunnaike, O.; Peter, F.; Kehinde, O. Intrapreneurship and innovation performance: A conceptual model. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, P.; Song, M.; Ju, X. Entrepreneurial orientation and performance: Is innovation speed a missing link? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.S.; Prabhu, J.C.; Chandy, R.K. Managing the Future: CEO Attention. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, P.; Junni, P. A contingency model of CEO characteristics and firm innovativeness The moderating role of organizational size. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 156–177. [Google Scholar]

- Herna, A.B. Strategic consensus, top management teams and innovation performance. Int. J. Manpow. 2010, 31, 678–695. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K.; Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. The development and validation of the organisational innovativeness construct using confirmatory factor analysis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2006, 7, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.E.; Kannan, P.K. (When) Does Third-Party Recognition for Design Excellence Impact Financial Performance in B2B Markets? J. Mark. 2018, 82, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. How Does Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Influence Innovation Behavior? Exploring the Mechanism of Job Satisfaction and Zhongyong Thinking. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgee, J.E.; Peterson, M. The Long-Term Impact of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Venture Performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 720–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevill, A.; Easterby-smith, M. Perceiving ‘capability’ within dynamic capabilities: The role of Owner-Manager Self-efficacy. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M.S. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy dimensions and entrepreneurial self-efficacy dimensions and higher education. Int. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2017, 21, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjay, K.S.; Rabindra, K.P.; Nrusingh, P.P.; Lalatendu, K.J. Self-efficacy and workplace well-being: Moderating role of sustainability practices. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 1692–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A.; Tse, H.H.M.; Schwarz, G.; Nielsen, I. The effects of employees’ creative self-efficacy on innovative behavior: The role of entrepreneurial leadership. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journal, S.E.; Cassar, G.; Friedman, H. Does self-efficacy affect entrepreneurial investment ? Strateg. Entrep. J. 2009, 3, 241–260. [Google Scholar]

- Bernoster, I.; Rietveld, C.A. Overconfidence, Optimism and Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.P.; Singh, R.P. Overconfidence: A Common Psychological Attribute of Entrepreneurs which Leads to Firm Failure entrepreneurs which leads to firm failure. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2020, 23, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dawwas, A.; Al-haddad, S. The impact of locus of control on innovativeness. Int. J. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 7, 1721–1733. [Google Scholar]

- Tinggi, S.; Manajemen, I.; Makassar, P.; Sulawesi, S. locus of control innovation performance of the business people in the small business and medium industries. J. Econ. Bus. Account. Ventur. 2012, 15, 373–388. [Google Scholar]

- Sup, D.B.; Sup, D.B. Identifying personality traits associated with entrepreneurial success: Does gender matter? J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2018, 27, 169–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hom, H. The effects of entrepreneurial personality, background and network activities on venture growth. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A. The influence of entrepreneurial personality on franchisee performance: A cross-cultural analysis. Int. Small Bus. J. 2020, 38, 605–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Frese, M.; Rauch, A.; Frese, M. Let’s put the person back into entrepreneurship research: A meta-analysis on the relationship between business owners personality traits, business creation and success and success. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2007, 16, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M.; Ermini, B. Risk attitude, product innovation, and firm growth. Evidence from Italian manufacturing firms. Econ. Lett. 2013, 118, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluisius, H.P. Does firm performance increase with risk-taking behavior under information technological turbulence? Empirical evidence from Indonesian SMEs. J. Risk Financ. 2018, 27, 2–19. [Google Scholar]

- Meroño-cerdán, A.L.; López-nicolás, C.; Molina-Castillo, F.J. Risk aversion, innovation and performance in family firms Risk aversion, innovation and performance in family firms. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2017, 27, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, Á. Determinants of the Propensity for Innovation among Entrepreneurs in the Tourism Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5003. [Google Scholar]

- Lazányi, K.; Virglerová, Z.; Dvorský, J. An Analysis of Factors Related to ‘Taking Risks’, according to Selected Socio- An Analysis of Factors Related to ‘Taking Risks according to Selected Socio- Demographic Factors. Acta Polytech. Hungarica 2019, 14, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lurtz, K.; Kreutzer, K. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Social Venture Creation in Nonprofit Organizations: The Pivotal Role of Social Risk Taking and Collaboration. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 46, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, N.M.; Price, L.L. Exploration in Product Usage: A Model of Use Innovativeness. Psychol. Mark. 1994, 11, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeraj, M. The Relationship between Optimism, Pre-Entrepreneurial Curiosity and Entrepreneurial Curiosity. Organizacija 2014, 47, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Making, D. Creation Opportunities: Entrepreneurial Curiosity, Generative Cognition, and Knightian Uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 45, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ser, M.A. CEO age and the riskiness of corporate policies. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 25, 251–273. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, M.; Schoar, A. Managing with style: The effect of managers on firm policies. Q. J. Econ. 2003, 118, 1169–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolli, T.; Renold, U.; Woerter, M. Vertical Educational Diversity and Innovation Performance. SSRN Electron. J. 2016, 27, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T. Studies on Female Force Participation in TMT and Technological Innovation. Master’s Thesis, California State Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tonoyan, V.; Strohmeyer, R.; Jennings, J.E. Gender Gaps in Perceived Start-up Ease: Implications of Sex-based Labor Market Segregation for Entrepreneurship across 22 European Countries. Adm. Sci. Q. 2019, 4, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissan, E.; Carrasco, I. Women Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Internationalization. Women’s Entrep. Econ. 2012, 6, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Dezs, C.L. Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 500, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, H.A.; Park, D. A Few Good Women—On Top Management Teams A few good women—On top management teams. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.; María, J.; Román, C.; van Stel, A. Exploring the impact of di ff erent types of prior entrepreneurial experience on employer fi rm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; van Gelderen, M.; Thurik, R. Drivers of entrepreneurial aspirations at the country level: The role of start-up motivations and social security. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2008, 4, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, K.; Ross, L. Financial Intermediation and Economic Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Olowu, A.U. Public Policy and Entrepreneurship Performance: The Divide and Nexus in West Africa; Stellenbosch University: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Patanakul, P.; Pinto, J.K. Program Management. In Program Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 106–118. [Google Scholar]

- Quartey, P. Regulation, Competition and Small and Medium Enterprises in Developing Countries. In Centre on Regulation and Competition Working Paper Series Paper No. 10; University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2001; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fiestas, I.; Sinha, S.; Associates, N. Constraints to Private Investment in the Poorest Developing Countries-A Review of the Literature; Nathan Associates London: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, J.P.J.; den Hartog, D.N. How leaders influence employees innovative behaviour. Empl. Innov. Behav. 2007, 10, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheng, Y.K.; June, S.; Mahmood, R. The Determinants of Innovative Work Behavior in the Knowledge Intensive Business Services Sector in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2017, 9, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. An Overview of Psychological Measurement. In Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders; Wolman, B.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 97–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick, D.C. Upper Echelons Theory. Palgrave Encycl. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, D.K.; Burmeister-lamp, K.; Simmons, S.A.; Foo, M.; Hong, M.C.; Pipes, J.D. I know I can, but I don’t fit: Perceived fit, self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 34, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faculty, F.; Sitki, M. Big five personality traits, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention A configurational approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1188–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Vancouver, J.B.; Thompson, C.M.; Williams, A.A. The Changing Signs in the Relationships Among Self-Efficacy, Personal Goals, and Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, G.B.; Neal, A. An Examination of the Dynamic Relationship Between Self-Efficacy and Performance Across Levels of Analysis and Levels of Specificity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 1088–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation Performance | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 0.0074 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Female | 0.0565 | −0.8119 * | 1 | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.1827 * | 0.0609 | −0.0473 | 1 | |||||||||

| Work Experience | 0.2647 * | −0.049 | 0.1081 | 0.0906 | 1 | ||||||||

| Degree and above | 0.3497 * | −0.2299 | 0.2744 * | 0.0801 | 0.0906 | 1 | |||||||

| Up to diploma | 0.0019 | 0.2108 | −0.2383 | 0.0554 | 0.0163 | −0.6882 | 1 | ||||||

| Locus of control | 0.3835 | −0.0941 | 0.0935 | 0.09 | 0.2542 | 0.2813 | −0.1014 | 1 | |||||

| Entrepreneurial Curiosity | 0.5314 | −0.1418 | 0.1732 | 0.0824 | 0.163 | 0.3023 | 0.0551 | 0.2984 | 1 | ||||

| Risk Attitude | 0.2221 | −0.1368 | 0.137 | 0.0758 | 0.0634 | 0.1636 | −0.0308 | 0.4411 | 0.3119 | 1 | |||

| Self-efficacy | 0.689 | −0.0706 | 0.0471 | 0.1397 | 0.0575 | 0.3763 | −0.1634 | 0.2499 | 0.4857 | 0.1263 | 1 | ||

| Perceived Public Policy Sup | 0.433 | −0.0046 | −0.0686 | 0.0548 | −0.1272 | 0.2892 | 0.0892 | 0.1369 | 0.3106 | 0.1498 | 0.4377 | 1 | |

| Perceived Public Policy Inst | −0.3679 | 0.0706 | 0.0375 | −0.0462 | 0.079 | −0.2293 | −0.0559 | −0.2123 | −0.2512 | −0.0608 | −0.329 | −0.8029 | 1 |

| MODEL 1 | MODEL 2 | MODEL 3 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | β | SE | T | Sig | β | SE | t | Sig | β | SE | t | Sig |

| Family Support | 0.357 | 0.1528 | 2.34 | 0.021 | 0.315 | 0.1068 | 2.96 | 0.004 | 0.306 | 0.1057 | 2.9 | 0.004 |

| Previous Exp. (Yes) | 0.158 | 0.1604 | 0.99 | 0.324 | 0.045 | 0.1107 | 0.41 | 0.685 | 0.029 | 0.1097 | 0.27 | 0.79 |

| Previous Exp. (No) | −0.187 | 0.147 | −1.27 | 0.204 | −0.13 | 0.0975 | −1.31 | 0.185 | −0.106 | 0.097 | −1.1 | 0.275 |

| Male | 0.036 | 0.1938 | 0.19 | 0.852 | 0.073 | 0.1924 | 0.38 | 0.705 | ||||

| Female | 0.022 | 0.208 | 0.11 | 0.915 | 0.051 | 0.206 | 0.25 | 0.805 | ||||

| Age | 0.002 | 0.0043 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.22 | 0.826 | ||||

| Work Experience | 0.382 | 0.0101 | 3.22 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.0105 | 2.46 | 0.015 | ||||

| Degree and Above | 0.143 | 0.195 | 0.74 | 0.464 | 0.009 | 0.2035 | 0.04 | 0.966 | ||||

| Up to Diploma Level | 0.127 | 0.193 | 0.66 | 0.512 | 0.165 | 0.1917 | 0.86 | 0.391 | ||||

| Locus of Control | 0.125 | 0.0607 | 2.05 | 0.042 | 0.144 | 0.0608 | 2.37 | 0.019 | ||||

| Entrepreneur Curiosity | 0.13 | 0.6079 | 2.09 | 0.038 | 0.124 | 0.0617 | 2.01 | 0.046 | ||||

| Risk Attitude | 0.044 | 0.0601 | 0.75 | 0.457 | 0.029 | 0.0599 | 0.5 | 0.617 | ||||

| Self-Efficacy | 0.831 | 0.111 | 7.49 | 0 | 0.854 | 0.1103 | 7.75 | 0.017 | ||||

| Perceived Public policy Supp | 0.192 | 0.2245 | 0.85 | 0.395 | 0.138 | 0.2235 | 0.62 | 0.539 | ||||

| Perceived Public policy Instab | −0.119 | 0.1794 | −0.67 | 0.505 | −0.147 | 0.1718 | −0.83 | 0.407 | ||||

| Degree above *Available Tech | 0.018 | 0.008 | 2.05 | 0.042 | ||||||||

| Adjusted R-Square | 0.0398 | 0.6078 | 0.6168 | |||||||||

| Over all F-statistics | 0.0291 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||

| Effect of independent Variables | - | 0.568 | ||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorcas, K.D.; Celestin, B.N.; Yunfei, S. Entrepreneurs Traits/Characteristics and Innovation Performance of Waste Recycling Start-Ups in Ghana: An Application of the Upper Echelons Theory among SEED Award Winners. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115794

Dorcas KD, Celestin BN, Yunfei S. Entrepreneurs Traits/Characteristics and Innovation Performance of Waste Recycling Start-Ups in Ghana: An Application of the Upper Echelons Theory among SEED Award Winners. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115794

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorcas, Kouame Dangui, Bekolo Ngoa Celestin, and Shao Yunfei. 2021. "Entrepreneurs Traits/Characteristics and Innovation Performance of Waste Recycling Start-Ups in Ghana: An Application of the Upper Echelons Theory among SEED Award Winners" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115794

APA StyleDorcas, K. D., Celestin, B. N., & Yunfei, S. (2021). Entrepreneurs Traits/Characteristics and Innovation Performance of Waste Recycling Start-Ups in Ghana: An Application of the Upper Echelons Theory among SEED Award Winners. Sustainability, 13(11), 5794. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115794