Strengthening Efforts to Protect and Safeguard the Industrial Cultural Heritage in Montilla-Moriles (PDO). Characterisation of Historic Wineries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. 2030. Agenda: Focus on the Sustainable Development Goals

1.2. Industrial Facilities for Wine-Making in the PDO Montilla-Moriles

1.3. Background: First News about Wineries in Montilla

“There are three ways of harvesting. As is done in Cordova, they have their homes in the vineyards, which they call wineries, with their cellars and winepresses, and there they make their wine, and they cook it, and they let it settle, and at the time of racking they bring it home clean, and if there are good errands there, let them be done well and clean, this is the best thing…”.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Conservation of Industrial Heritage

3.2. Heritage Importance, Heritage Values and Authenticity Attributes

3.3. Possible Strategies and Approaches for the Conservation of Wineries

3.4. The Architecture of the Wineries

3.5. Historic Wineries in Montilla

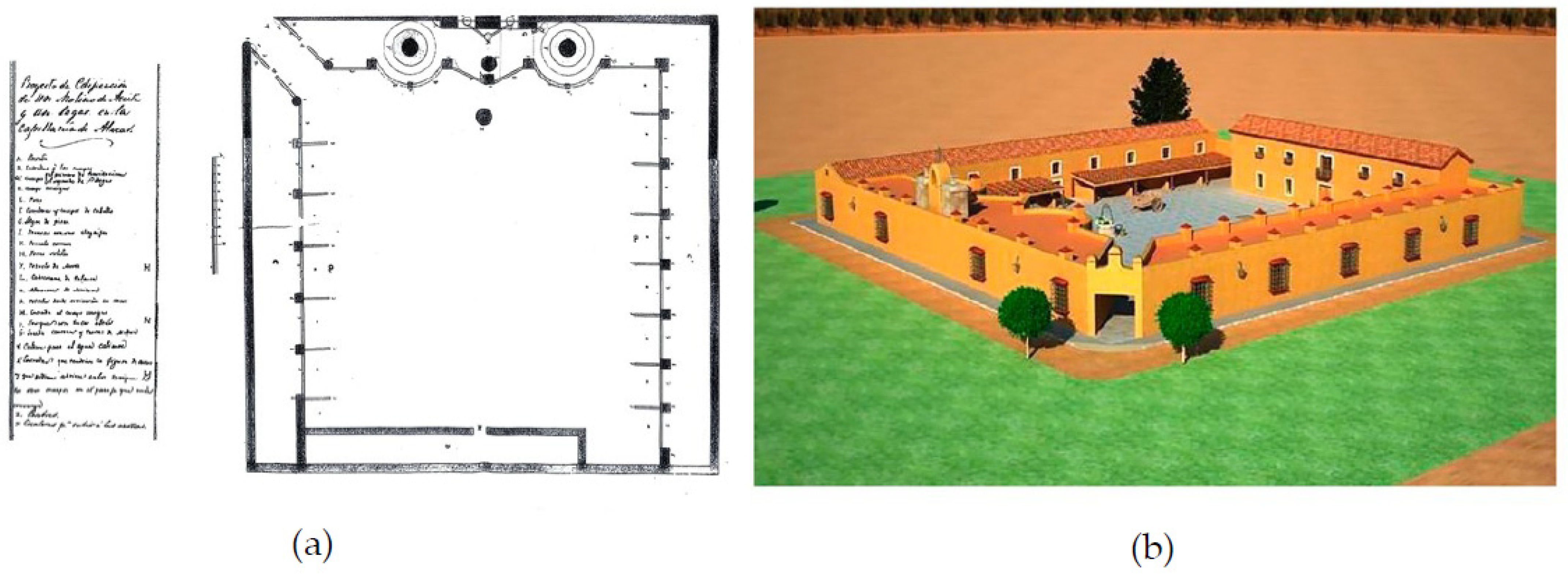

3.5.1. Case Study: Lagar de la Capellanía (Winery of the Chaplaincy)

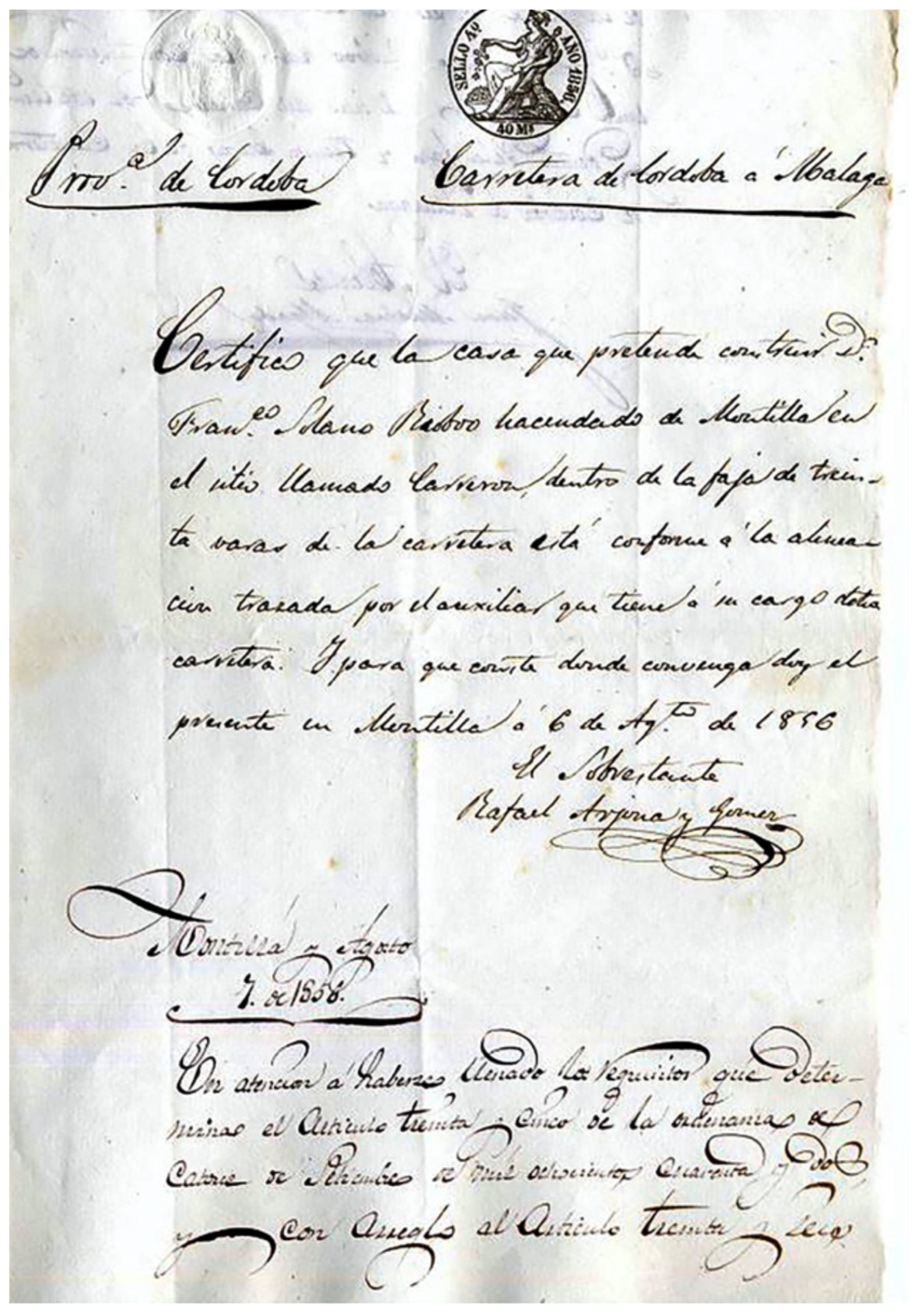

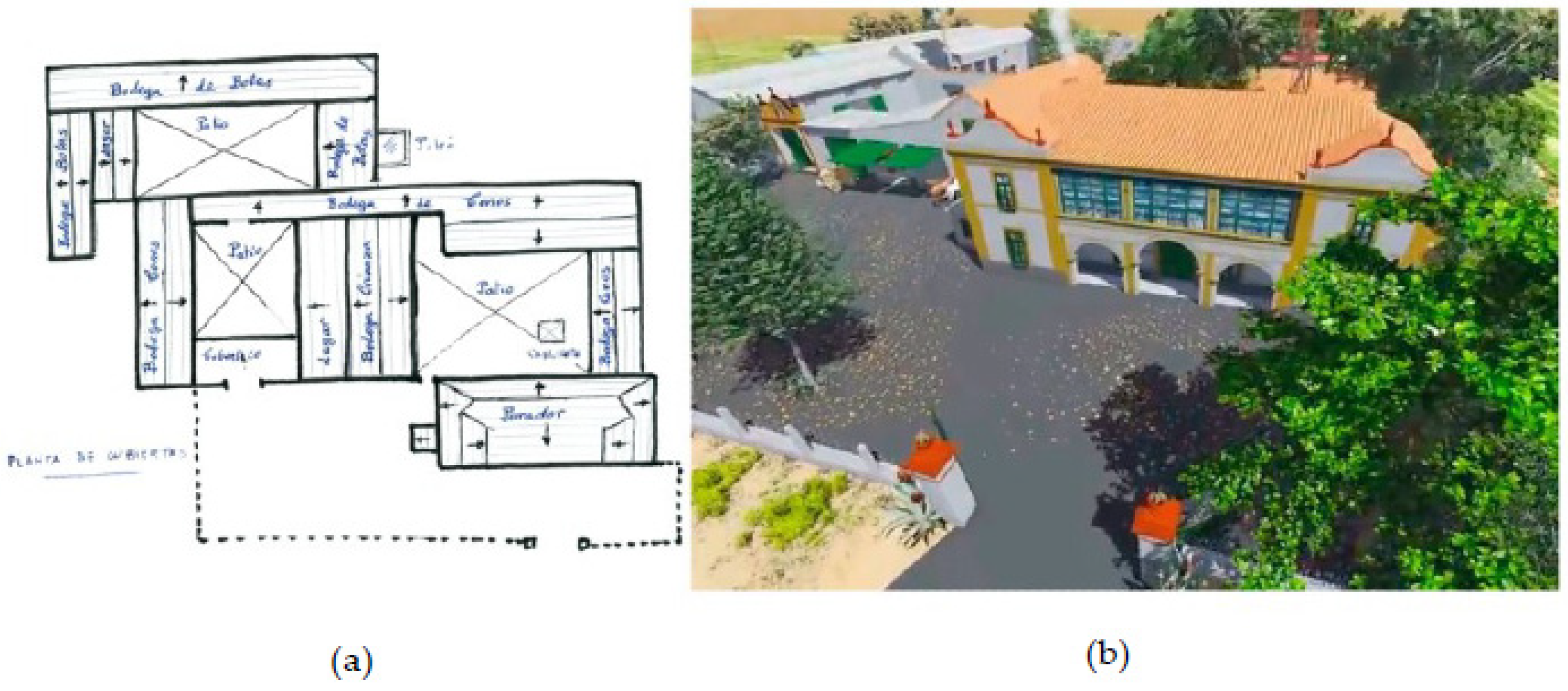

3.5.2. Case Study: Lagar “el Parador de Montilla” (The Montilla Inn Winery)

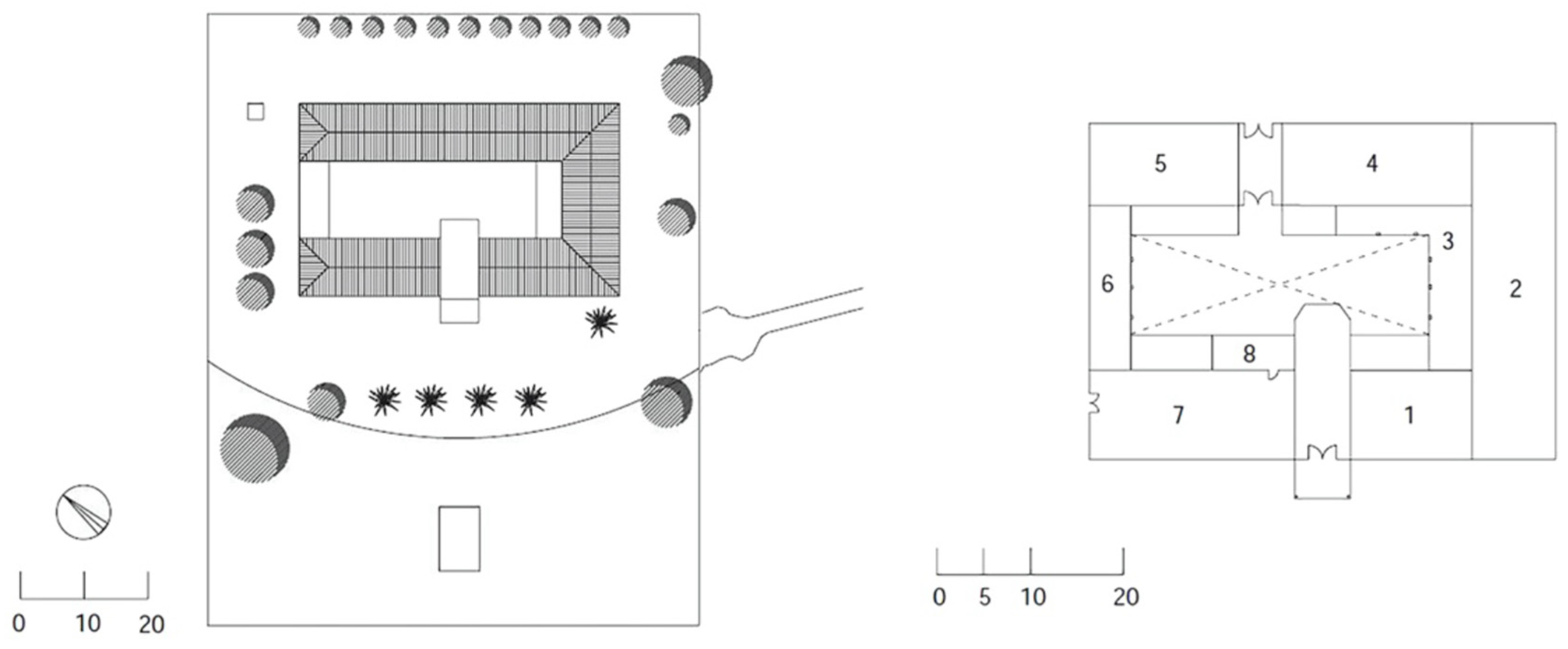

3.5.3. Case Study: Lagar de La Inglesa (Winery of the English Woman)

3.5.4. Case Study: Lagar de Las Monjas (Winery of the Nums)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. The Sustainable Development Agenda. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Ministerio de Cultura. El Plan Nacional de Patrimonio Industrial (“The National Plan for Industrial Heritage”). Madrid. 2011. Available online: http://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/planes-nacionales/dam/jcr:b34f01e5-c3d9-497b-bc7a-ecba1ac65d22/04-industrial-eng.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Serrano, E.; González-Amuchastegui, M.J. Cultural Heritage, Landforms, and Integrated Territorial Heritage: The Close Relationship Between Tufas, Cultural Remains, and Landscape in the Upper Ebro Basin (Cantabrian Mountains, Spain). Geoheritage 2020, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Culture for the Agenda 2030; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organizations: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/flipbook/culture-2030/en/Brochure-UNESCO-Culture-SDGs-EN2.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Calvo-Serrano, M.; Castillejo-González, I.; Montes-Tubío, F.; Mercader-Moyano, P. The Church Tower of Santiago Apóstol in Montilla: An Eco-Sustainable Rehabilitation Proposal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullino, P.; Beccaro, G.L.; Larcher, F. Assessing and Monitoring the Sustainability in Rural World Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14186–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pj, C.M.S. Preservation and Conservation of Rural Buildings as a Subject of Cultural Tourism: A Review Concerning the Application of New Technologies and Methodologies. J. Tour. Hosp. 2013, 2, 1000115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naranjo Ramírez, J. El valor paisajístico de lo utilitario. La casa rural en el viñedo cordobés: “los lagares”. In En: Martínez De Pison, E. Y Ortega Cantero, N.; del Paisaje, L.v., Ed.; Autonomous University of Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 293–316. [Google Scholar]

- Portero Laguna, J. Metodología Para El Conocimiento De Un Edificio Agroindustrial Integrando Distintas Disciplinas. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cordoba, Córdoba, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Triviño-Tarradas, P.; Carranza-Cañadas, P.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F.-J.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, E.J. Evaluation of Agricultural Sustainability on a Mixed Vineyard and Olive-Grove Farm in Southern Spain through the INSPIA Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landi, S. Rural Landscapes of the 20th Century: From Knowledge to Preservation. Arch. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2019, 12, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slámová, M.; Belčáková, I. The Role of Small Farm Activities for the Sustainable Management of Agricultural Landscapes: Case Studies from Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prada Llorente, E.I.; Riesco Chueca, P.; Herrero Tejedor, T. Landscape and image: Heritage and form in the cultural construction of agrarian land. Estudios Geograficos 2013, 74, 557–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vlamia, V.; Kokkorisb, I.P.; Zogarisc, S.; Cartalisd, C.; Kehayiasa, G.; Dimopoulos, P. Cultural landscapes and attributes of “culturalness” in protected areas: An exploratory assessment in Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirós García, M. El Libro de Agricultura de Gabriel Alonso de Herrera: Un texto en busca de edición. Criticón 2015, 123, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, G.A. El Libro De Agricultura. In Libro Segundo; 1790; Volume CXXI, p. 71. Available online: http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000079905&page=1 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- MAPA. Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Gobierno de España. Obra de Agricultura, 1513. Primera Edición. 2020. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/ministerio/servicios/informacion/plataforma-de-conocimiento-para-el-medio-rural-y-pesquero/centenario/indice-1513.aspx (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Fomento, Infraestructuras y Ordenación del Territorio. Cortijos, haciendas y lagares: Arquitectura de las grandes explotaciones agrarias de Andalucía. Provincia de Córdoba. Sevilla. 2006. Available online: https://ws147.juntadeandalucia.es/obraspublicasyvivienda/publicaciones/01%20ARQUITECTURA%20Y%20VIVIENDA/cortijos_haciendas_y_lagares_en_andalucia/cortijos_haciendas_cordoba/cordoba_tomo2.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Madoz, P. Diccionario Geográfico-Estadístico-Histórico De España Y Sus Posesiones De Ultramar; Establecimiento tipográfico de P. Madoz y L. Sagasti: Madrid, Spain, 1845; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez de las Casas Deza, L.M. Corografía Histórico-Estadística De La Provincia Y Obispado De Córdoba (1840–1842); Monte de Piedad y Caja de Ahorros: Cordoba, Spain, 1840. [Google Scholar]

- Vizetely, H. Facts about Aherry Gleaned in the Vineyards and Bodegas of Jerez, Seville, Moguer & Montilla Districts during the Autum of 1875. Londres, 1876. Ward, Lock, and Tyler, Warwick House. Available online: https://euvs-vintage-cocktail-books.cld.bz/1876-Facts-About-Sherry-by-Henry-Vizetelly/X/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- IAPH (Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico). Paisaje Vitivinícola de Montilla; Data Sheet; Consejería de Cultura: Sevilla, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Pino, J. Montilla, 1950–1975. In Entre La Historia Y La Memoria; Montilla: Cordoba, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Triviño-Tarradas, P.M. Evolución y mejoras para el manejo sostenible de la explotación vitivinícola en la D.O.P. Montilla-Moriles. Evaluation and Improvements for the Sustainable Management of the Wine-Making Farm in the PDO Montilla-Moriles. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Badia-Miró, M.; Tello, E.; Valls, F.; Garrabou, R. The grape phylloxera plague as a natural experiment: The upkeep of vineyards in catalonia (spain), 1858–1935. Aust. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2010, 50, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duran, J.I.D.L. Wine cathedrals: Making the most of masonry. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Constr. Mater. 2013, 166, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. Consejería de Economía y Conocimiento. Atlas de Histórica Económica de Andalucía. SS XIX-XX. 2020. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/atlashistoriaecon/atlas_cap_17.html (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Consejo Regulador de Montilla-Moriles. Estadísticas. 2020. Available online: https://www.montillamoriles.es/es/ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Baraja Rodríguez, E.; Plaza Gutiérrez, J.I.; Prada Llorente, E.I. Naturaleza, Territorio y Ciudad en un Mundo Global. Actas del XXV Congreso de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles. In Atributos y Valores Patrimoniales de los Viñedos Tradicionales en las Provincias de Zamora y Salamanca: El caso de los arribes del Duero; A.G.E. (ASOCIACIÓN GEÓGRAFOS ESPAÑOLES): Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, M. Montilla y Su Comarca: Enciclopedia-Guía Antológica; Valdés M.: Sevilla, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- González San José, M.L. Enoturismo y Entornos Sostenibles. 2017, Volume 193, p. a399. Available online: http://arbor.revistas.csic.es/index.php/arbor/article/view/2207 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Pardo Abad, C.J. El Patrimonio Industrial En España: Análisis Turístico Y Significado Territorial De Algunos Proyectos De Recuperación; Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles: Seville, Spain, 2010; Volume 53, pp. 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- García, N.T. La Memoria del Pasado Industrial. Conservación, Reutilización Y Creación De Nuevos Equipamientos. RPH Rev. Electrónica Patrim. Histórico 2016, 19, 72–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla Plaza, L. El Parque Minero de Almadén. Un Modelo De Recuperación Del Patrimonio Minero Industrial. Herit. Museography 2011, 1, 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Arnáiz, M.M.; Rodríguez, E.B.; Hernando, F.M. Criterios de la UNESCO para la declaración de regiones vitícolas como paisaje cultural: Su aplicación al caso español. BAGE 2019, 80, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez Carrión, J.M.; Ramon Muñoz, J.M. La vitivinicultura y la valorización de su patrimonio industrial, cultural y natural. In Áreas. Revista Internacional De Ciencias Sociales; University of Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2010; Volume 29, pp. 148–155. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/areas/article/view/115631 (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Aladro-Prieto, J.M. Bodegas, lagares y casas de viñas. AH Andalucía en la Historia, año XVII, 66, octubre-diciembre. 2019, pp. 14–17. Available online: https://www.centrodeestudiosandaluces.es/publicaciones/descargando/2356/documento (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Álvarez-Areces, M.A. Patrimonio industrial. Un futuro para el pasado desde la visión europea. In APUNTES; 2008; Volume 21, núm. 1; pp. 6–25. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/apun/v21n1/v21n1a02.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Luque Romero, F.; Agudo Torrico, J.; Cobos, J. Cultura Material De Carácter Tradicional En La Provincia De Córdoba; Gever S.L.: Cordoba, Spain, 1985; Volume IV, pp. 137–193. [Google Scholar]

- Marine, N.; Arnaiz-Schmitz, C.; Herrero-Jáuregui, C.; Cabeza, M.R.O.; Escudero, D.; Schmitz, M.F. Protected Landscapes in Spain: Reasons for Sustainability of Conservation Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino Simal, J. Arquitectura de la industria en Andalucía; Instituto de Fomento de Andalucía: Jaen, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bellido Vela, I.D. Diego de Alvear y Ward. Un innovador de la agroindustria. La prensa hidráulica. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas Salas, M. El molino del duque de Montilla Y La Influencia Del Monopolio Señorial En La Arquitectura Oleícola. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Archivo Histórico Municipal de Montilla (Cordoba-Spain). Legajo 980 B, Expediente 1. Available online: https://www.montilla.es/areas_municipales/cultura/archivo_historico (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Montesinos, F.J.A. Reconstrucción virtual del lagar El Parador. Unpublished Master’s Degree Project, University of Cordoba, Córdoba, Spain. 2012. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmjGV76s_n8 (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Cultura y Patrimonio Histórico. Guía Digital del Patrimonio Cultural de Andalucía. 2020. Available online: https://guiadigital.iaph.es/inicio (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Muñoz, P.; Morales, M.; Mendívil, M.; Juárez, M.; Muñoz, L. Using of waste pomace from winery industry to improve thermal insulation of fired clay bricks. Eco-friendly way of building construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 71, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Marqués, M. Evolución del diseño de proyectos de bodegas de vinos en la provincia de Córdoba; University of Cordoba: Cordoba, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, J.; Cano, P.; Melero, J.; España, M.; Moreno, J. Aplicaciones de la digitalización 3D del patrimonio. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2010, 1, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bekele, M.K.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni, E.S.; Gain, J. A Survey of Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality for Cultural Heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2018, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merino-Aranda, A.; Castillejo-González, I.L.; Velo-Gala, A.; de Paula Montes-Tubío, F.; Mesas-Carrascosa, F.-J.; Triviño-Tarradas, P. Strengthening Efforts to Protect and Safeguard the Industrial Cultural Heritage in Montilla-Moriles (PDO). Characterisation of Historic Wineries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115791

Merino-Aranda A, Castillejo-González IL, Velo-Gala A, de Paula Montes-Tubío F, Mesas-Carrascosa F-J, Triviño-Tarradas P. Strengthening Efforts to Protect and Safeguard the Industrial Cultural Heritage in Montilla-Moriles (PDO). Characterisation of Historic Wineries. Sustainability. 2021; 13(11):5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115791

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerino-Aranda, Antonia, Isabel Luisa Castillejo-González, Almudena Velo-Gala, Francisco de Paula Montes-Tubío, Francisco-Javier Mesas-Carrascosa, and Paula Triviño-Tarradas. 2021. "Strengthening Efforts to Protect and Safeguard the Industrial Cultural Heritage in Montilla-Moriles (PDO). Characterisation of Historic Wineries" Sustainability 13, no. 11: 5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115791