1. Introduction

Despite all the attempts to figure out the precise factors that contributed to the recent global financial crisis (GFC), the answer is still inconclusive but firm in some elements. One of these parts was the restatement of the global corporate governance (CG) principles of financial firms presupposing that governance failures were heavily responsible for these institutions’ deficiencies during the GFC [

1]. In particular, sound remuneration policies in banks were fundamentally the focus of the controversy because bank compensation is a politically charged variable and the amounts usually exceed what is considered normal for the rest; therefore, stakeholders overall and the general public in particular (especially voters) seem to be more involved and thus interested in such governance faced during downturns. The point is that people believe that the variable portion of total remuneration rewarded greed and, in the end, failure [

2]. Accordingly, the GFC has absolutely put under severe scrutiny remuneration policy and consequently the incentives design that affects risk-taking by managers in the banking industry [

3], influencing the sustainability of its operating practices. One may discover studies that discuss the relation between the GFC and the remuneration policy, e.g., [

4,

5,

6,

7]; however, the existing empirical evidence is limited [

8,

9] and sometimes contradictory to the general opinion [

10]. Nevertheless, investors, supervisors, regulators, and even politicians have been discussing the level and structures of compensation plans that appeared to exacerbate risk-taking and inspire short-termism. So as to shirk another financial collapse, the European Union (EU) approved and issued several regulations for remuneration requirements in CDR III [

11,

12,

13]. Though all the EU efforts put into remuneration practices suggest commitment in the sense of aligning risk, performance, and remuneration to reduce excessive risk-taking in banks, good does not necessarily imply desirable. In fact, due to all the unintended consequences of such compensation rules, the word “flexibility” has been recently incorporated into the regulation [

14], Whereas 8, maybe to cover its back.

Many are the changes that have been produced over time and thus implemented into the EU remuneration policies to avoid excessive risk-taking in banks. Among all the reforms, we can highlight two main compensation mechanisms aimed at easing bank managers’ risk appetite for variable payments. Firstly, mechanisms that rely on instruments and longer deferrals, including retention periods such as malus and clawback; and secondly, limiting the variable compensation (the bonus cap). Accordingly, I postulate that in doing so, the regulations might exacerbate moral hazard problems, generate more information asymmetries, and create “hidden” compensation practices that lower transparency and accelerate the disinterest of bank managers and owners when their banks fail. Maybe, instead of balancing profit and risk to avoid excessive risk-taking not aligned with business strategy, it creates unsustainable profits that might harm the economic and social sustainability of society.

Among other factors to recover banks’ reputation, some authors argue that outcomes of CSR reporting should be especially notorious in the banking sector, e.g., [

15]. Several reasons explain such interest [

16]. First, transparency, corporate accountability, and public trust need to be recovered from the last GFC. Hence, due to their importance in the whole economy, banks are called on to have broader moral responsibility. Second, as a result of the aforementioned, banks are supposed to be accountable to other stakeholders (creditors, borrowers, government, supervisors, regulators, employees, etc.). Financial firms must be fairly responsive to all their demands and ensure that bank corporate practices are aligned with broader societal interests [

17]. As a benefit of the CSR initiative by banks, we can highlight that CSR reinforces bank operations’ legitimacy [

18], facilitates due diligence and evaluation [

19,

20], reduces information asymmetries [

21], enhances financial conditions and credit rating [

22], and improves compliance, thereby reducing internal costs [

23]. CSR actions are expected to affect compensation schemes. If CSR improves banks’ performance, remuneration plans are likely to be structured more transparently and will contemplate a longer time frame, which reduces risk appetite from managers—an “insurance-like” effect [

24]—and accounting-based incentives compensation. Nevertheless, reputational and economic effects from such practices will always be confronted, so achieving the optimal level of CSR would not penalize good CG strategies and would avoid conflicts of interest [

25]. Accordingly, I postulate that encouraging banks to engage more in CSR practices would probably automatically rectify or balance potential problems coming from remuneration schemes.

The aim of this study is not only to show the impact of the new EU remuneration policy on bank executives’ compensation incentives, but also to unravel the origin and backstage of these new EU remuneration rules, as well as critically examine the impact of the CSR initiative on bank CEO compensation.

For that purpose, the research methodology is as follows. I focus attention on the main bank material risk takers (MRTs, or identified staff) to be visible bank head managers who must play different roles to bring order in the riskiness that governs the banking industry. The data from the EBA reports [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] spanning from 2010 to 2017 was collected because it provides remuneration practices of the higher earners (HEs—those that earn more than EUR 1 million a year) in the EU banking industry. Once collected, we graphically saw a tendency that comes to confirm the previous postulations. The results show certain trends that came to evidence perverse incentives to discretion. Moreover, as the institutional theory states, the context strongly influences governance and then executive remuneration [

34], and this was seen by comparing the UK with the rest of EU. Overall, we appreciated an abrupt growth in HEs, especially from 2013 to 2015 (61.8% in general, and 135% for the identified staff); a great proportion of HE and identified staff arose from the UK (80%). The overall variable-to-fixed ratio experienced a significative reduction of 168%, but was accomplished in terms of deferrals. We also noticed that the UK bank managers will be the most affected by the remuneration guidelines (at the time they will probably leave the EU) since HEs from the UK are the most paid in the EU. In addition, we also observed that EU bank remuneration substantially but dangerously favored fixed pay over the variable component. On average, each HE increased their fixed pay to the detriment of variable pay; however, with the exception of the UK, the main remuneration components completely turned their position. That is, the fixed part surpassed variable pay. All these points denote clear preferences and herding behavior by HEs from the UK to stay in their country and a potential migration of EU best-performing bank managers to the UK when Brexit is fulfilled. In addition, we argue that CSR practices might solve most of the questionable and controversial negative effects of the new EU remuneration rules as long as bank managers partially resign to economic aspects and opt for social reputation.

The contribution of this paper is twofold. Firstly, having a restrictive cap on executive bonuses (which is defined as having above-market salaries and high but capped bonus opportunities), more complex remuneration schemes, and risk management assessment may lead to perverse incentives by bank managers that might threaten the financial system’s sustainability: (i) increasing the fixed component; (ii) less involvement in bank discipline by economic agents; (iii) boosting earnings management, and income smoothing practices in particular, since they create incentives to accept “bad risks” and reject “good risks” (when a bank manager reaches the bonus cap, additional efforts are not compensated anymore, so they tend to transfer actual realized profits into subsequent periods—this idea is somehow associated with financial fraud and earnings quality. For further information and reasoning about earnings quality, see [

35,

36,

37,

38], among others); and finally, (iv) intensifying adverse selection problems (the EU scenario would be only attractive for bad-performing bank managers and would have negative repercussions on bank competitiveness, whereas good performers would move to other countries where their efforts are not regulated downwards). In contrast, CSR strategies would reduce cash-based compensation and information asymmetries, would disincentivize discretionary practices that partly impair financial transparency and thus stability, and would retain high-quality employees.

Secondly, the unintended consequences of the new EU remuneration policies may be direct consequences of having made decisions in an inappropriate way, and several arguments come to light. First, competing and traditional theories in explaining bank executives’ remuneration are not fully successful. For instance, just resolving principal-agent conflict is not enough, because risk-taking by bank managers has important social costs, and maybe the “inside debt” can be more adequate than maximizing shareholders’ value [

39]. Another example is that the unequal bargaining power between the board of directors and executives is not taken into account [

40]. Either the “salary fan” is considered or losses are more meaningful than gains if they are equal [

41]. Second, longer deferral rules better align the risk horizons of decisive individuals with long-term safety and soundness, but this ruling should not ignore that they are much shorter than the estimated length of the credit cycle of banks (8 to 30 years on average). Third, government intervention in corporate governance policies, especially in remuneration structure, is one of the main drivers [

42]. We must not forget that the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and prudential organism are composed of politicians and bank supervisors who seek to guarantee the financial stability of the system. In order to avoid potential bailouts (that they have to face for sure if systemic banks fail), they allow or partly encourage bank managers to engage in excessive risk-taking [

3] or even use accounting choices to smooth income (e.g., via loan loss impairments), which results in a false stability to the detriment of financial transparency [

43]. For better or worse, but interestingly, politicians and prudential regulators have not responded yet with more binding remuneration regulations to the actual evidence of the existing weakness in the banking sector across the EU [

44], in spite of the introduction of the stringent bonus cap. Instead, policymakers, banks, and regulators should also promote the transparency of CSR disclosures [

17,

45].

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the reader to CEO compensation and the role of CSR in banks.

Section 3 explains in more detail EU bank remuneration policies.

Section 4 explores the idea that accounting-based incentives compensation is likely to reinforce attitudes towards building countercyclical buffers and manage earnings, which includes income-smoothing behaviors. In turn, CSR investment may reduce such discretion.

Section 5 presents the unintended consequences derived from the new EU remuneration policies, and (numerical and CSR) actions to circumvent the EBA guidelines. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

3. European Bank Remuneration Rules

Undoubtedly, worldwide technological, economic, financial, and regulatory changes modified and in turn reshaped the global economy in a more complex scenario. Practices such as massive and uncontrolled off-balance-sheet financing of loans and the use of sophisticated derivates increased bank profitability by creating risks that at a glance were (and are) not easily visible to the rest of the actors, such as borrowers and lenders, or even to the supervisory or regulatory system, which weakened the financial stability purpose of the Basel regulation. In this sense, revisions to the Basel system tackled some of these habits, but that was not the case for the regulation of compensation. It is true that prudential regulation implemented changes such as the measurement of risk-adjusted performance, the scope of new standards, the proportionality principle, etc., due to the increase in pressure from the media, politicians, and the general public, passing from a supervisory to a more regulatory approach. However, though directives were concerned about bankers’ remuneration (e.g., provisions on regulatory capital), national implementation exposed shortcomings [

6]. All this effectively improved risk management systems and reformed areas of prudential regulation, such as capital adequacy and some banking organizational requirements, instead of intervening directly in bankers’ incentives.

As pointed out by the literature on this topic, e.g., [

85], the philosophy of shareholder primacy is the main stumbling block to far-reaching reforms. That is, paying executives for just increasing the share price or return on equity (more than return on assets) was a misleading practice that triggered economic disasters. Furthermore, leaving remuneration schemes to bank boards and shareholders encourages excessive risky actions by executives, whereas regulators are unable to even perceive impressive credit fluctuation and the risk associated with it. Even though it occurs, the truth is that historically bad corporate governance mechanisms always result in enormous costs for shareholders, but also for taxpayers, which seems to indicate that “banks managers and owners have limited interests in the consequences of bank failures and systemic risk” [

86,

87]. Though one may find many bank failures in Europe (e.g., CAM or Bankia in Spain; Commerzbank in Germany; ING in the Netherlands, RBS, Lloyds, and HBOS in Scotland; National Bank of Greece; or, more recently, PNB Banka in Latvia), the assistance to banks is provided privately or even publicly when their bankruptcy may threaten or collapse systemic stability.

3.1. Failed Governance and Failed Incentives in the 2008 Financial Crisis?

It is commonly asserted that the economic impairment in the last financial turmoil was mainly driven by bank management scandals (spread to other industries), together with a lack of transparency and the subsequent government bailouts [

64]. These circumstances therefore undermined public trust in the banking industry [

88]. As suggested by countless authors, e.g., [

17,

89], banks must put all their efforts to build their reputation again, triggered by the new and challenging environment coming from the global financial crisis (GFC).

The endless debate about the precise factors that caused the recent GFC will be eternally discussed, with no consensus. An approximation sits in the de Larosière report, in which the members of the high-level group on financial supervision in the EU concluded that, among others, remuneration and incentives schemes within financial institutions were part of the main causes of the GFC. The reason behind it is that it “contributed to excessive risk-taking by rewarding short-term expansion of the volume of (risky) trades rather than the long-term profitability of investments” [

90] (p. 10). At this point, it is remarkable to clarify that the GFC was not driven by excessive risk-taking, but rather the erroneous and inappropriate expectation that housing prices would eventually appreciate forever. In fact, bonus plans were sketched assuming a continued appreciation, and not the contrary. However, that does not justify wrong, bad, or weak corporate governance policies.

We may find many changes in the corporate governance reporting, but some are especially crucial for the banking industry. Remuneration policy is the most direct instrument that affects bank governance and bank manager behavior; however, this is not the only one. There are two that are particularly important as well. First, the role of auditors as enforcers is essential [

91,

92]. Auditors play a significant function in detecting and preventing material frauds and in taking into account a wide range of information in reaching audit judgement; in fact, auditors must evaluate firms’ internal control, which is the process designed, implemented, and maintained by those with governance, management, and other personnel to achieve the firms’ objectives, reliability, effectiveness, and efficiency of operations, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. Clearly, evaluating the internal control influences bank managers’ incentives. Second, as stated by Gebhardt and Novotny-Farkas [

93] and García-Osma et al. [

43], is the power and independence (from both politicians and the banking sector) of national prudential supervisors. These two governance characteristics of national prudential supervisors are supposed to influence accounting and bank managers’ incentives. For instance, powerful supervisors are predicted to influence the accounting practices (income smoothing) of banks and shape the properties of accounting numbers, and the feature of being independent mitigates such an effect.

Surfing the literature on the compensation matter, one realizes the existence of works discussing the link between financial institution remuneration policy and the GFC (e.g., [

4,

5,

6,

7]); however, the empirical evidence on this relation is scarce but surprising, e.g., [

8,

9]. The study of Fahlenbrach and Stulz [

8] slightly contradicted the notion that having a better alignment of management interests with those of the shareholders permits taking on less (excessive) risk. In this sense, they showed some evidence that bank CEOs performed worse during the crisis and obtained worse stock returns and worse return on equity. With respect to Ali Shah et al. [

9], though with a US sample, they found no clear evidence to support bonus plans having caused the GFC. In fact, the results showed that bonuses reduced banks’ risk-taking (total, systematic, and idiosyncratic risks) in the pre-crisis period, and that more confining shares and options granted to CEOs spanning 2009 and 2013 also decreased banks’ risk-taking. Apparently, long-time-to-maturity options reduce excessive risk, but whether CEOs will decline risky (high-return) projects remains inconclusive.

Despite the limited empirical references, the incentives in such remuneration practices have played a serious role in making financial decisions. The existence of powerful incentives to increase leverage and risk makes banking regulation even more decisive than in other sectors. For instance, in order to better align executives’ interest with that of shareholders (to maximize returns to shareholders), executives have usually been rewarded with stock options and bonuses linked to return on equity. These forms of compensation encourage “seek bigger and riskier bets” behaviors [

85]. As shown by Haldane [

94], increasing leverage may hike return on equity, which necessarily is accompanied by an increase in risk. To do that, bank employees are encouraged by their superiors to make risky loans or offer other convoluted financial products so as to meet revenues targets, without taking care of borrowers’ repayment as a consequence of “high-powered incentives” via remuneration. Probably, CEOs and the rest of the top managers had the right incentives (short- and long-term incentives), but maybe the problems came from deficient risk management systems at some large banks whose decisions and their aftermath affect the whole economic system. For example, top managers did not know or understand what their dependent staff were doing. Now, did bank governance contribute to the financial crisis? Is remuneration policy partly responsible for bad bank governance?

No doubt, the financial crisis triggered the restatement of the global corporate governance principles of financial institutions “in the belief that governance failures contributed to these institutions’ failures in the crisis” [

1] (p. 10). One the one hand, the bank governance perspective has substantially changed over time. Even though the “principles of corporate governance for banks” were originally published by the BCBS (by the OECD in general) in 1999 to assist supervisors, many legal systems shifted after the crisis from a supervisory to a regulatory approach. Taking a collaborative part in bank management is not enough, but the 2015 edition of the BCBS guidelines also calls for an “effective implementation of sound corporate governance” that requires “legal, regulatory and institutional foundations.” On the other hand, compensation plans are more in the spotlight than corporate governance issues per se. Remuneration is more politically charged so voters are more involved and then interested in downturns.

According to the above, the financial crisis has definitely put under serious scrutiny both remuneration policy and incentive design in the banking industry [

3], although some empirical studies found no evidence that deficiencies in corporate governance arrangements were a fundamental originator of the financial crisis, e.g., [

10]. Nevertheless, investors, supervisors, regulators, and even politicians have been discussing the level and structures of compensation plans that appeared to exacerbate risk-taking and inspire short-termism. Even though “the success of the EU regulation of bank compensation practices is contingent on the global adoption of such rules” [

6,

87], these guidelines seek to align risk, performance, and remuneration in order to reduce excessive risk-taking by the banking industry.

In addition to compensation rules, CSR practices (sustainability disclosure) may help in restoring banks’ reputation and avoiding an inappropriate lack of transparency in remuneration plans. For instance, CSR reporting facilitates transparency but may be detrimental to maximizing bank CEO remuneration because it tends to reduce firms’ risk profiles [

45,

95]. For that reason, among others, the most widespread and used CSR reporting framework—the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards—encourage banks to report this non-financial information with the Financial Services Sector Supplement (FSSS) that particularly addresses and guides financial institutions [

96,

97].

3.2. Recent Regulatory Development in Europe

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) was formed in April 2009 as an international body that monitors and deliver recommendations about the global financial system. It was established by the 20 leading economies (G20) and was mainly composed of politicians (governments) and bank supervisors (central bank governors) to guarantee financial stability. Despite its short run, the FSB immediately issued the Principles for Sound Compensation Practices, which the Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS) subsequently used to propose the CEBS Guidelines on Remuneration Policies and Practices in 2010. Therefore, this legislation contained compensation proposals based on prudential oversight and included that member states should ensure that financial firms have remuneration policies that promote “sound and effective risk management” and do not feed risk appetite.

The timeline of remuneration rules has not been a quiet path but rather a continuous give-and-take among European member states. The FSB’s proposals were drafted under an international perspective and framework that left room for country-specific regulation. In this sense, the UK and USA had ultimately opposing opinions in such practices, so they decided to accept them partially. In January 2010, in the European context, the Financial Services Authority (FSA) implemented the FSB principles but with remuneration rules for UK-based banks, published initially on 12 August 2009. Later, in January 2011, remuneration requirements were incorporated into the Capital Requirement Directive III (CDR III), applicable to all EU jurisdictions. An example of this is that more than 50% of variable remuneration awards are required to be delivered in non-cash instruments (shares, debt), which creates incentives aligned with long-term value creation and the time horizon of risk.

To sum up the next steps, the EBA took over the ongoing functions and responsibilities of CEBS from 1 January 2011 [

11]. The “Guidelines on sound remuneration policies” was issued by the EBA under the 2013/36/EU Directive (CRD IV) [

12] and Regulation (EU) No. 575/2013 [

13] (hereafter Guidelines). These Guidelines were applicable as of 1 January 2017 and addressed to ensure fair play, taking into consideration not only the nature, scale, and complexity of banking activities but also covering all employees.

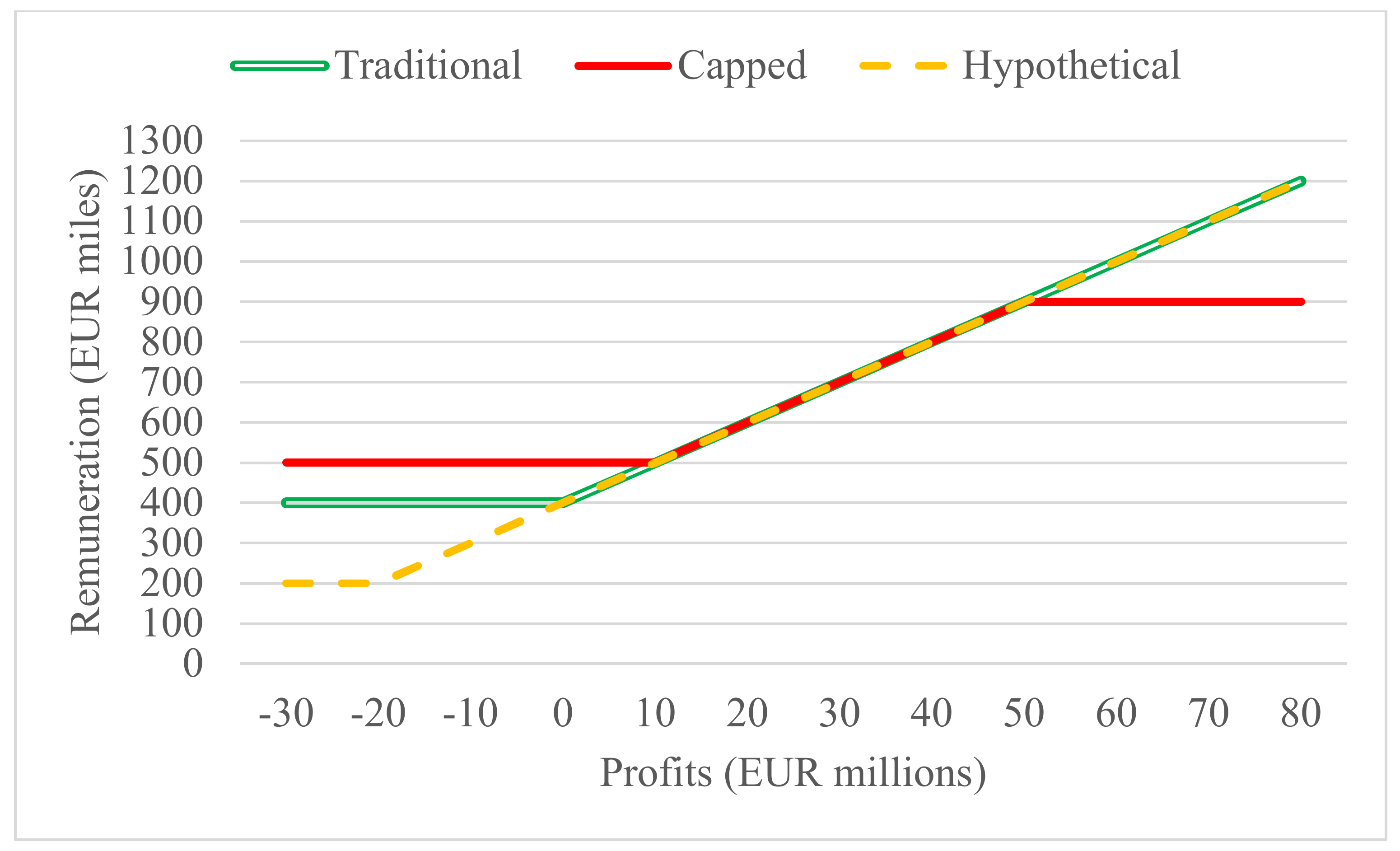

3.3. Banks’ Remuneration before and after the 2008 Financial Crisis

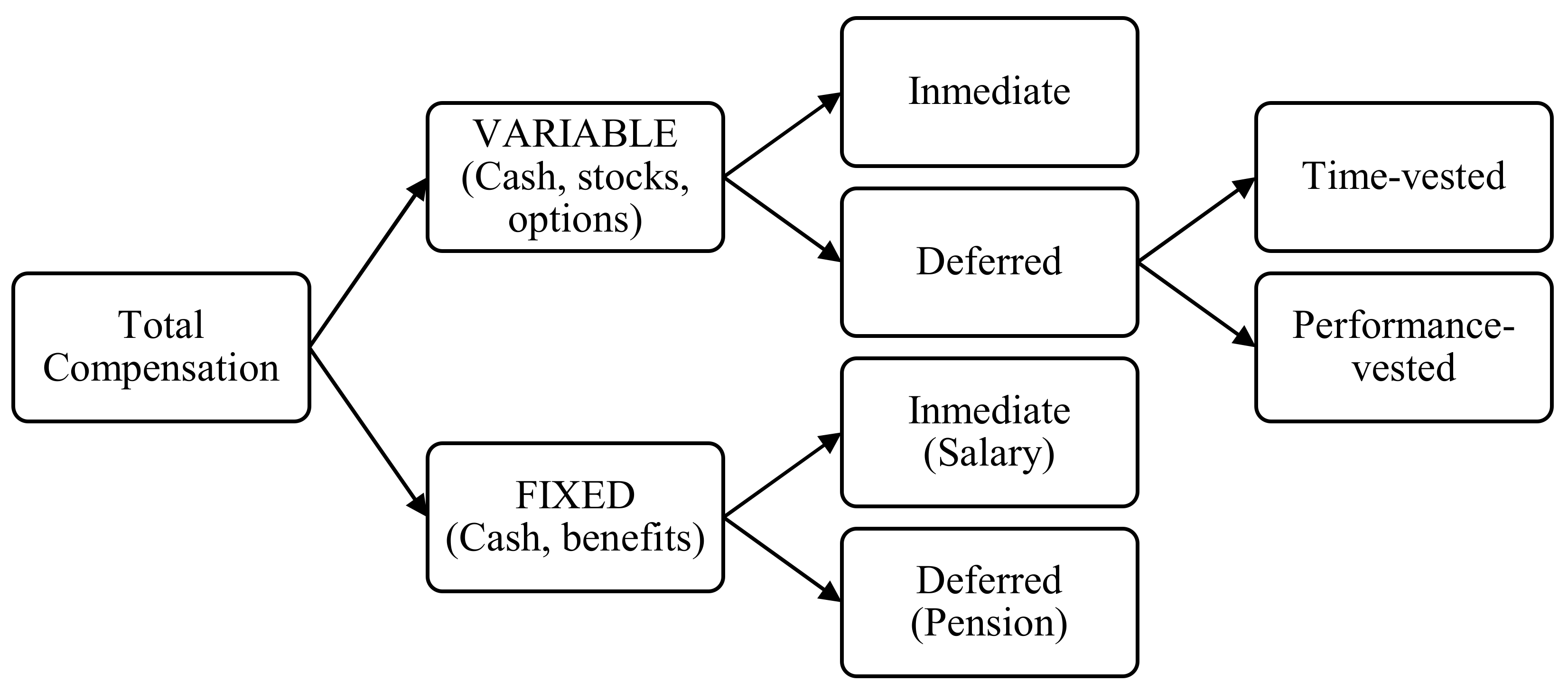

The financial crisis supposed a serious turning point to change what was being done until then. Before the crisis, no bonus cap stood; there was no restriction on cash vs. non-cash instruments in variable remuneration; deferral, malus, and clawback (according to the Guidelines, retention is an instrument to align identified staff (i.e., staff whose professional activities have a material impact on the institution’s risk profile) compensation with the long-term interest of the bank. Retention is an ex-post risk adjustment mechanism that consists of lowering awarded cash remuneration or reducing the number or value of awarded instruments in response to an adverse bank development via value or risk. It may take the form of malus or clawback. Malus is a soft clawback and applies to the deferred but non-vested bonus, whereas clawback occurs when variable remuneration has already been paid or vested) arrangements were not regulatory requirements; and performance measures were not risk weighted. In the post-crisis things have changed in a more constrictive sense. A bonus cap of 100% was installed, although the ratio variable to fixed can increase to 200% with shareholders’ approval. The premise behind this scheme is that the expectation of large variable compensation awards intrinsically creates adverse risk incentives that cannot be merely alleviated by ex-ante and ex-post risk adjustments. Therefore, a ceiling on variable pay should hinder excessive risk-taking, as the upside benefits are limited. The palpable consequence is a shift to higher levels of fixed remuneration to offset the variable reduction. (a shift to higher levels of fixed remuneration is not always possible. The compensation must be considered fixed when it is non-discretionary, non-varying, predetermined, and thus non-revocable, and independent of performance. If there is any doubt about the nature of the fixed payment, then it is automatically classified as a variable component (Guidelines, paragraph 116).)

The main compensation adjustments are especially linked to the variable component. For instance, 50% of this must be paid in cash and the other half via non-cash instruments. Additionally, 40% of all variable remuneration should be paid upfront, with 60% deferred. In this respect, all deferred remuneration that has not yet vested may be subjected to malus.

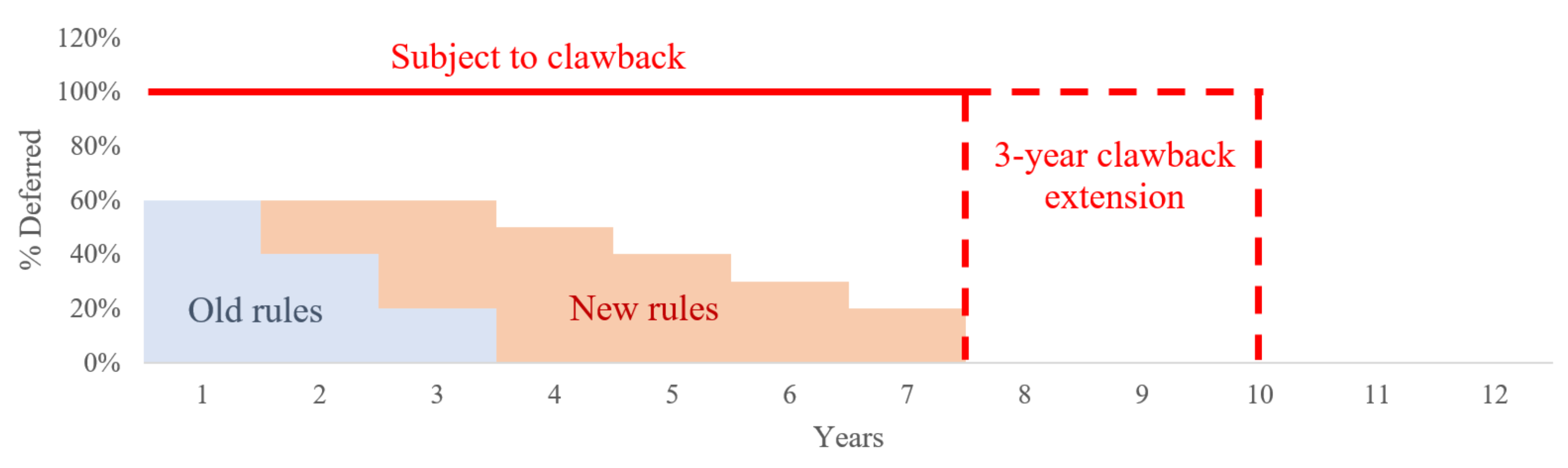

Figure 2 graphically shows the longer deferral rules in comparison to old ones that went into force at the start of 2016. It reflects the desirable claims of the Financial Regulatory Authority (FRA), the FCA, and the PCBS. The rationale is that longer deferral periods better align the risk horizons of key individuals with the long-term safety and soundness of the firms for which they work. However, the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) expressed discontent in their November 2012 financial stability report that they appeared insufficient because deferrals should also seek to align awards to the usual business cycles that banks operate in and underpin financial industry performance. They concluded that long-term incentive plans (LTIP) were much shorter (3 to 7 years) than the estimated length of the credit cycle (8 to 30 years), though more in line with the average business cycle (5.5 years).

The Guidelines also mention that clawback arrangements are now part of regulatory requirements since they act as a provision, taking back vested variable remuneration as a result of misconduct or risk management failings. Performance metrics (to go deeper in the relation between performance metrics and CEO remuneration, see Doucouliagos et al. [

98], Murphy [

42], Dutta and Fan [

99], or Tahir et al. [

100]) are ex-ante adjusted for risk-taking and may be split into four: (i) risk-adjusted returns metrics (e.g., economic profit or return on risk-weighted assets), (ii) prudential metrics (e.g., healthy balance sheet or capital levels as a share of risk-weighted assets), (iii) strategic metrics (e.g., market growth, cost savings, or investment in human resources), and (iv) conduct metrics (e.g., customer outcomes or compliance with regulation). The fundamental idea is to account for operation, credit, and liquidity risks in financial institutions and contribute to the safety, soundness, and stability of the financial system. Therefore, forward-looking performance measures make it possible, or at least facilitate, decision-making in loan-loss provisioning to operate with an aggressive or conservative credit policy.

Finally, the proportionality principle is part of the Guidelines’ backbone, which is also encoded in CRD IV. This principle matches the risk profile, risk appetite, and strategy of any financial institution but considers dissimilarities as well in their characteristics (size, geographical location, structure, business model, and cycle). Therefore, this flexibility tamed the claimers who advocated for the no application of compensation policies because it requires more refined remuneration plans for larger and “crypted” banks without dragging smaller ones to do the same but in a proportional manner. However, an exception to the proportionality axiom is the bonus cap, which applies to all corporate governance and risk management areas in all banks.

Say-on-Pay Issue

In line with the above, the remuneration policy therefore involves two board committees: a risk committee and remuneration committee. The former controls the risk appetite and the later cooperates with the supervisory figure in designing the remuneration policy. Even though the latter is compulsory for significant financial entities but desirable in the rest, the EBA recommends that the annual general meeting (AGM) approve such a compensation protocol. In this sense, the only way to agree on a variable to fixed ratio of 200% is by AGM approval, and at this stage the “say-on-pay” (SOP) issue comes out.

The “say-on-pay” concept refers to the right of shareholders (AGM) to vote on whether they are for or against the remuneration of identified staff. This became popular and was empowered by international organisms as a consequence of the perceived boost in executives’ rewards [

72]. However, the debate is served because of the contrasting points of view [

47,

101,

102,

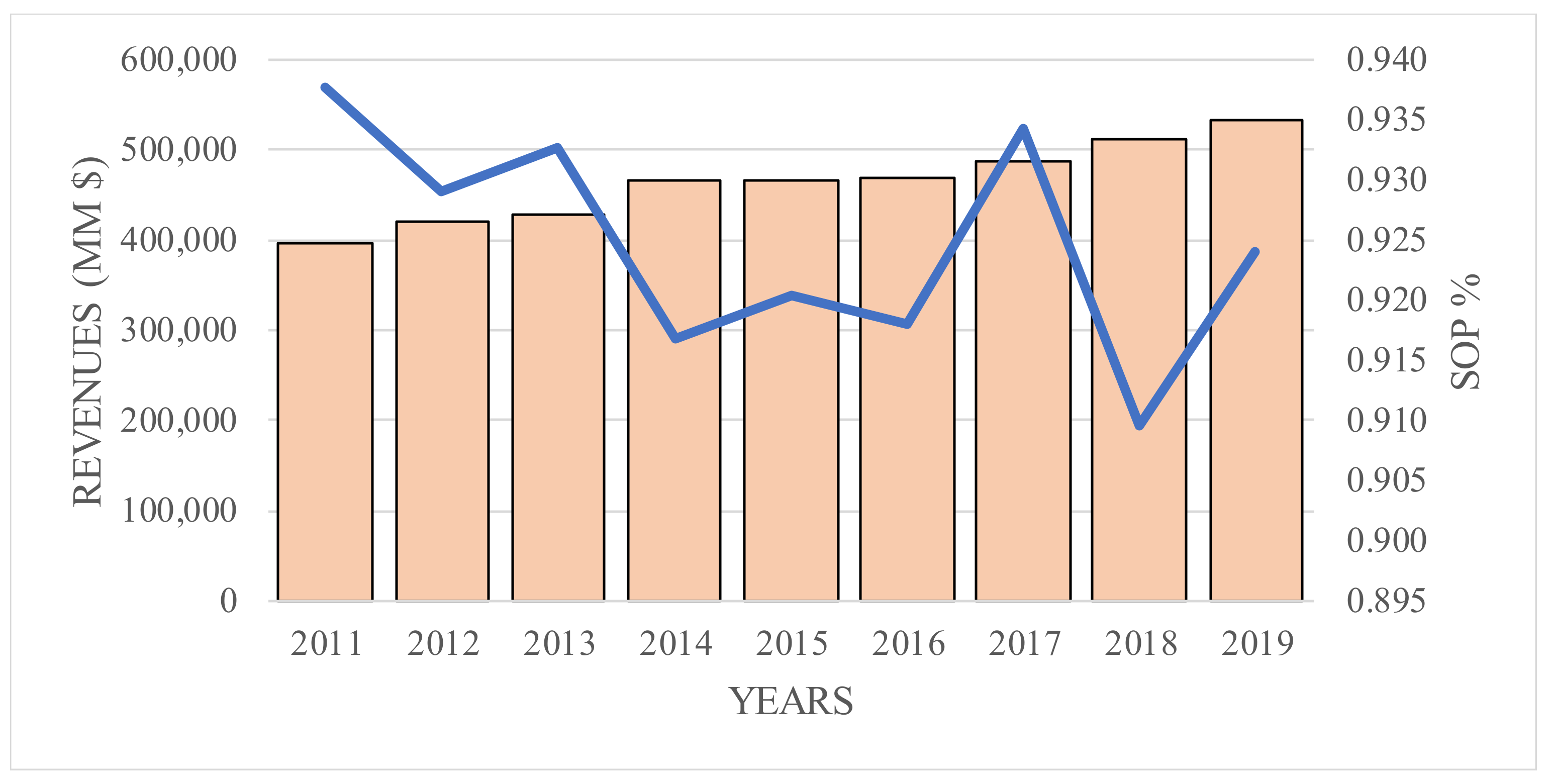

103]. Defenders argue that it strengthens board of directors (BoD) and shareholder relationship, whereas critics believe that it is reactionary and counterproductive rather than proactive, claiming that it diminishes the authority or supremacy of the BoD. When analyzing the data on this matter, one may realize its importance and make their own conclusions. To do so, we collected the SOP data from the 301 financial firms listed in S&P 500, the most representative world market growth index, spanning from 2011 to 2019.

Figure 3 matches the average SOP% in favor of the remuneration policy and the revenues achieved over time. Even though the observed relation does not imply causality, the numbers seem to contradict the evidence of Fisch et al. [

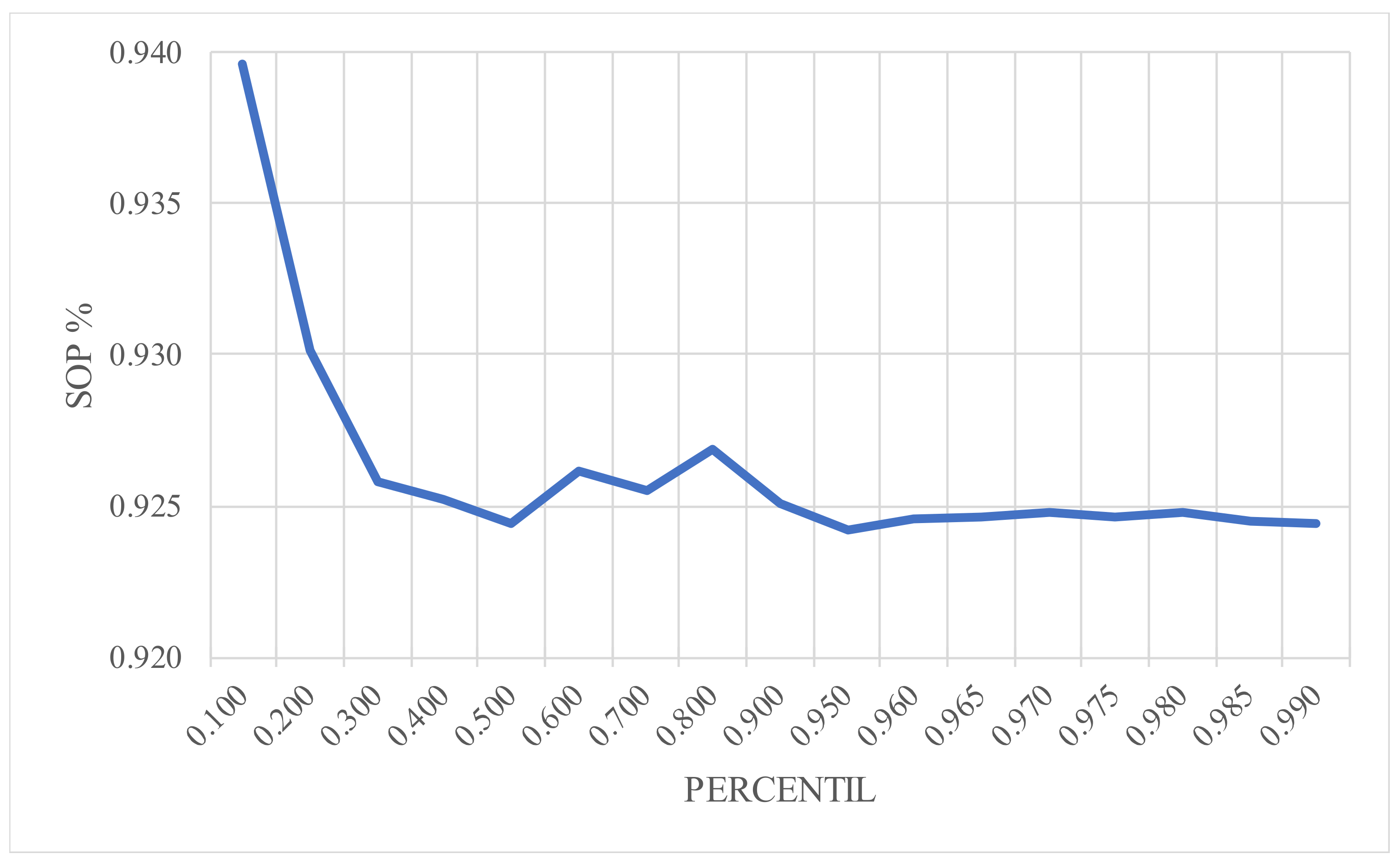

103]. They found that when firms perform well, shareholders do not care about excess payment; however, the historical SOP data slightly denote less consensus (decreasing SOP%) among shareholders when revenues increase. Although the empirical findings in the literature may notice caution about the potential value of the SOP vote, the global financial institutions appear to evidence that executive remuneration plans may still be short-term structured in spite of the new Guidelines and perhaps top managers are still overpaid according to their risk exposure and interest with the bank. Furthermore, revenue distribution is relevant, alluding to the notion of “one size does not fit all.” As can be observed in

Figure 4, shareholders are more prone to being in favor of remuneration policy when revenues are lower and inverse. However, this last behavior changes when revenues range between 0.5 and 0.95 percentiles (USD 162 MM and USD 4443 MM). This representative 45% of the sample with more shareholder approval evidences that issuers’ and owners’ approaches to the vote on executive compensation are still in a developing process [

103].

3.4. The Interest of the Government in Banks’ Remuneration Practices

Many empirical studies have taken into consideration for their analysis the effect of size because the scrutiny level depends in most of cases on how large the bank is; in particular, some of them have made quartiles or percentiles partitions [

103,

104]. Bank size and strategies mostly respond to national culture. This is a key point because executive compensation has evolved over time and thus is responsive to economic and political fluctuations. In fact, all competing theories and broad approaches must be determined by firms’ institutional environment [

42]. For example, Almadi and Lazic [

105] demonstrated how institutional factors influence CEO incentive-based compensation and then earnings management practices. More specifically, Anglo-Saxon countries such as the UK and Australia count more on earnings smoothing for earnings management than others, and their CEOs are paid on average 14.5% higher than their next highest paid executives, whereas the percentage of other countries such as Germany and Austria is reduced to 10.7%. Moreover, Anglo-American countries have higher levels of investor protection, stricter legal enforcement, and better governance systems.

Despite explaining executive remuneration becoming tough and convoluted, we must not forget that government intervention has been one of the meaningful drivers of such corporate governance policies [

42]. Indeed, the FSB is composed of politicians and bank supervisors, so they probably account for the financial stability but also for their supremacy when shaping compensation legislation, so any argument discounting political factors is riskily sketchy. For that reason, the Guidelines require effective supervisory oversight, firstly at the micro level (risk and remuneration committees) and secondly at the macro level (supervisory bodies). Related to the latter, the supra supervisory organisms must guarantee the implementation of sound compensation policies and practices. In case of failure, they would first take prompt and persuasive remedial actions and if necessary, appropriate corrective actions to offset any potential systemic disgrace, such as increasing capital requirements or pressuring banks on loan loss provisioning.

Coming from the 2008 financial crisis, central banks and governments implemented state aid procedures to safeguard financial stability and banking industry activity. That implied rescuing ailing banks from bankruptcy and preventing potential systemic collapses. Clearly, if upgrading wide corporate governance does not work, then bank regulation and supervisors have to interfere in bank governance, which also covers compensation policy, trying to balance equity, debt, and risk governance [

87]. In terms of lobbying, regulators and supervisors eventually became a very involved and powerful stakeholder in banks. The excessive risk-taking by banks may generate large social costs (negative externality) and shocks to the whole economic system [

48], and that is one explanation of why banks strongly drag the attention of politicians and governments agree to protect them, even though this state intervention, which is also communicated and examined by the Commission, may take the form of public ownership or financial support [

106] and not always solve the problem. As noted by Calomiris and Jaremski [

86] and de Andrés et al. [

87], the comprehensive Guidelines try to convince the EBA and the single supervisory mechanism (SSM), but the social importance of banks may weaken the supervisory effectiveness in confining systemic risk because, among others, a stakeholder approach would be preferable to a shareholder approach. Calomiris and Haber [

107] showed that regulatory failures often trigger prudential reforms. Barth et al. [

108] found that market discipline may act as a systemic risk stabilizer, opposite to prudential requirements. Brown and Dinc [

109] evidenced the potential of election years, which somehow slows down the closure of insolvent banks due to the regulatory recognition of major bank losses. Maybe all these results need to be fixed by the desirable and dreamed governance characteristic of being independent from the political and industrial perspectives [

43].

3.5. Are the UK and EU Destined to Be Rivals?

Going back to stabilization aids, regardless of its form, national and international support is not costless. In return, in the European context, the compliance of several conditions is “compulsory”: stringent dividend policy, higher solvency ratio, and limits to executive remuneration. However, there are notable differences in the application of the Guidelines on sound remuneration policies in Europe, concretely between UK and the rest of the EU. It is noticeable that the first major financial regulator to respond to the financial crunch with the establishment of a remuneration code was the UK Financial Services Authority (FSA), which was the forebear of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) of April 2013. This code has been progressively amended to meet CDR III and IV requirements. The final Remuneration Code eventually formed part of both FSA and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) Handbooks. Notwithstanding both, UK organisms share responsibility for assessing compliance with the Remuneration Code. The FCA takes it from a conduct point of view whereas the PRA considers it from a prudential perspective.

All UK firms must comply with all existing national requirements on remuneration policy and practices and also with all EBA Guidelines aspects, but with several specific clarifications. For instance, the main relevant exceptions we may point to are the PRA notification to the EBA in noncompliance with the bonus cap (100% in general and 200% with shareholders’ approval) and that the PRA and FCA will retain their current approach of requiring the proportionality level-three financial institutions to disapply the pay-out process rules and bonus cap. Even though this kind of exigence does not go beyond a simple demand so far, it becomes transcendental since it brings to light two existing and potential threats: (i) excessive compensation in some countries in the European area, and (ii) rapid migration of bank executives to other countries with “laxer” remuneration policies.

It is generally and justly believed that international financial standards, more specifically governance and remuneration rules, are usually formulated so that countries may have certain flexibility to implement them and thus smooth or dilute conflicts of interest within the individual regions [

1]. This is because as the institutional theory indicates, the context powerfully influences governance and executive pay [

34]. In line with this, overall problems on executive pay matters fundamentally arise when comparing Anglo-Saxon and non-Anglo-Saxon countries. The two threats mentioned above mainly relate to this endless comparison and it clearly manifests in the reality, where the new European map drafted by Brexit denotes a direct punishment for EU banks, with the exception of UK financial institutions (in this scenario, UK banks would not be under EU compensation requirements), and at the same time it gives UK banks a room to receive the best executives, whose predilection for higher variable remuneration is notable but reasonable, making divergence in the EU more accentuated, if possible.

To see that, we collected the data from EBA reports on top European countries [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33], which span from 2010 to the of end 2017. Doing so allowed us to observe EU banking remuneration trends over time regarding higher earners (HEs) (those who earn more than EUR 1 million a year). Furthermore, it also allowed us to distinguish those considered the main material risk-takers (identified staff or MRTs by the academia, though the concept is not clear enough [

56]) from those who are not (non-identified staff).

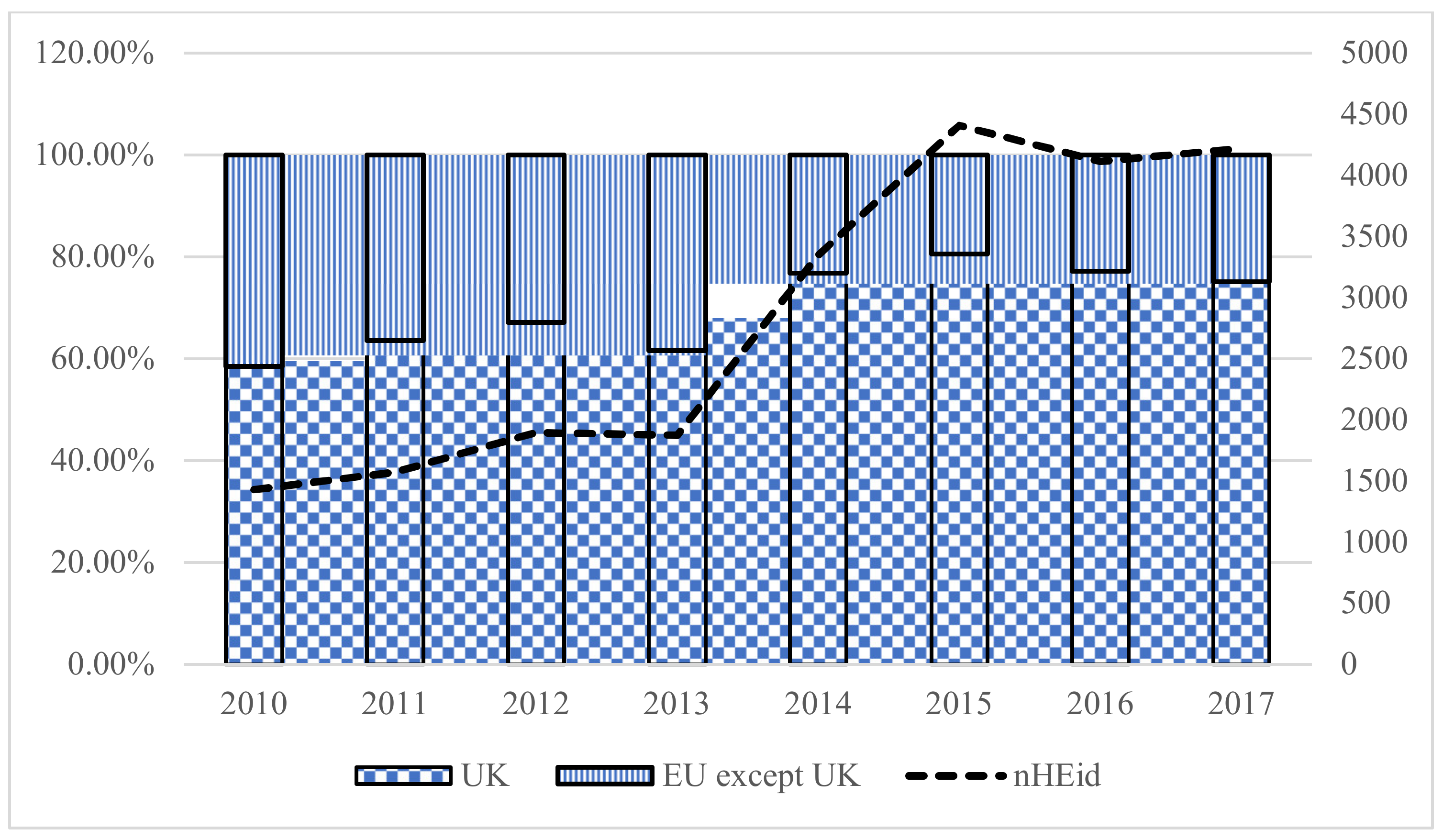

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the proportion and number of HEs and identified staff, respectively, by region, that is, in Europe and the UK separately. We observed a significant increase in HEs over time, especially from 2013 to 2015, with a growth of 61.8% (5142 HEs), and a steeper slope referring to identified staff of 135% (4408 HEid). This trend held from 2015 to date. Another important issue to point out is the fact that the vast majority of HEs and identified staff (close to 80%) arose from the UK rather than the rest of the EU. According to these basic and preliminary results, it is remarkable that the EU eventually became concerned with remuneration policies and made relevant advances towards the identification of MRTs; however, EU standard setters may have partially ignored the UK environment, at a time when it was probably leaving the European Union.

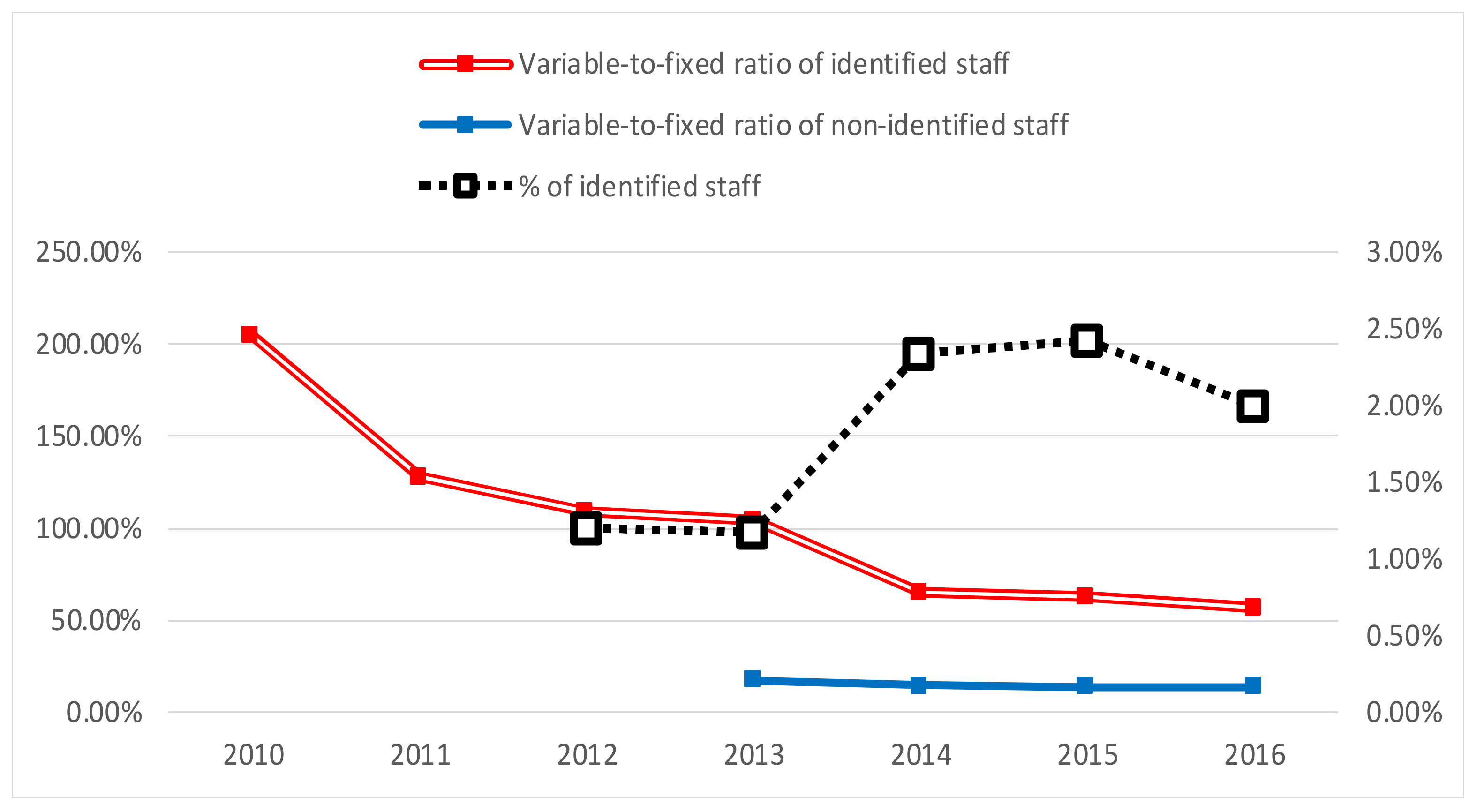

As the central debate and controversy lies on the variable-to-fixed remuneration ratio (bonus cap), we next plotted several significative and intuitive charts that explain the compensation reality. Following the remuneration rules,

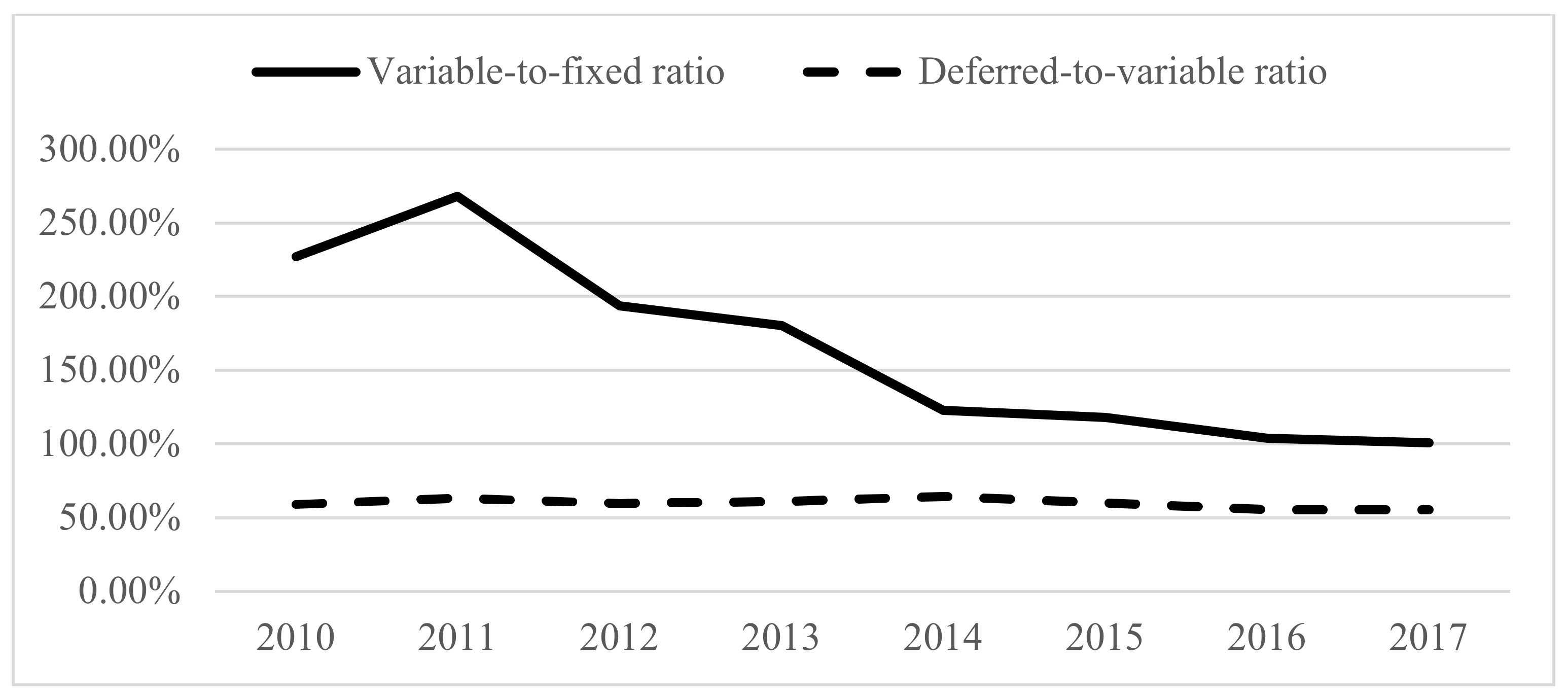

Figure 7 presents an indicative reduction in the bonus cap (from 200% to close to 50% on average) for professionals who had a material impact on banks’ risk profile, alluding to a previous excessive pay, whereas this ratio held for non-identified staff. We also noticed an increase of 2.5 times the percentage of identified staff compared to before 2013. This tendency could be explained for the 2013 PCBS recommendation for larger deferral periods, which in theory better aligns the risk prospect of key individuals with the long-term safety and soundness of banks, even though they should be estimated considering both business and credit cycles. From a wider HE perspective, the variable-to-fixed remuneration ratio experienced a significative decline of 168% (from 268% in 2011 to 100% in 2017), as seen in

Figure 8. In addition, the compensation legislation was accomplished in terms of deferrals (about 60% of the variable part was deferred, then 40% was vested immediately).

The popular term opened to extensive discussion has undoubtedly been the bonus cap. Even though the EBA Guidelines connect remuneration with performance, risk profile, and the business cycle more than ever before, the EBA seems to be conscious that its Guidelines may motivate fixed pay practices to mutate. Managers and top executives will look for other alternatives to offset the limits for variable-to-fixed ratios, especially in banks.

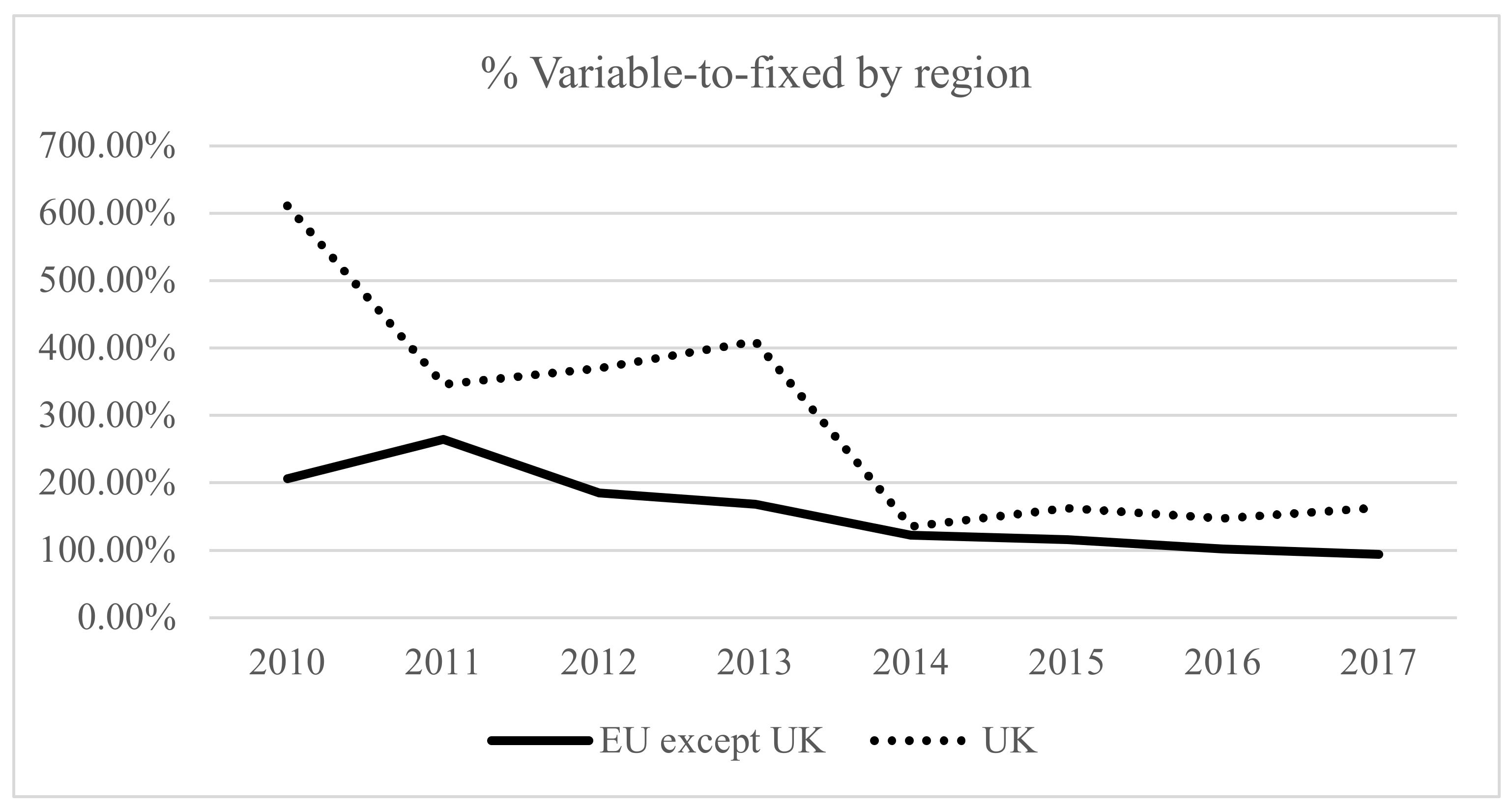

Figure 9 demonstrates that even after the beginning of the financial crunch, the HEs from the UK were still the most paid in EU, and the rest of the EU countries did not almost exceed the 200% limit. However, the bonus cap forced them to reduce it and thus to converge with the rest of the EU parties. As can be seen, the limit of 200% was accomplished after 2014, when the CRD IV provisions came into force, including the bonus cap and criteria for MRTs. Undeniably, the variable-to-fixed ratio consists of two numbers: The numerator is the variable component, whereas the fixed remuneration occupies the denominator. If restrictions on the bonus cap constrains executive pay, then the solution is either lowering the bonus pay and keeping the fixed remuneration, or maintaining the variable pay in exchange for increasing the fixed part or a mixed of them, and that is indeed what happened when remuneration rules were implemented. However, this behavior may have been induced by political pressure [

5] or maybe as a consequence of having higher reference points for their remuneration [

110]—for instance, if the reference mark was before the Guidelines application, afterwards executives would prefer at least the same as before, so when the bonus cap was applied, the only alternative to boost pay would be to expand the fixed component.

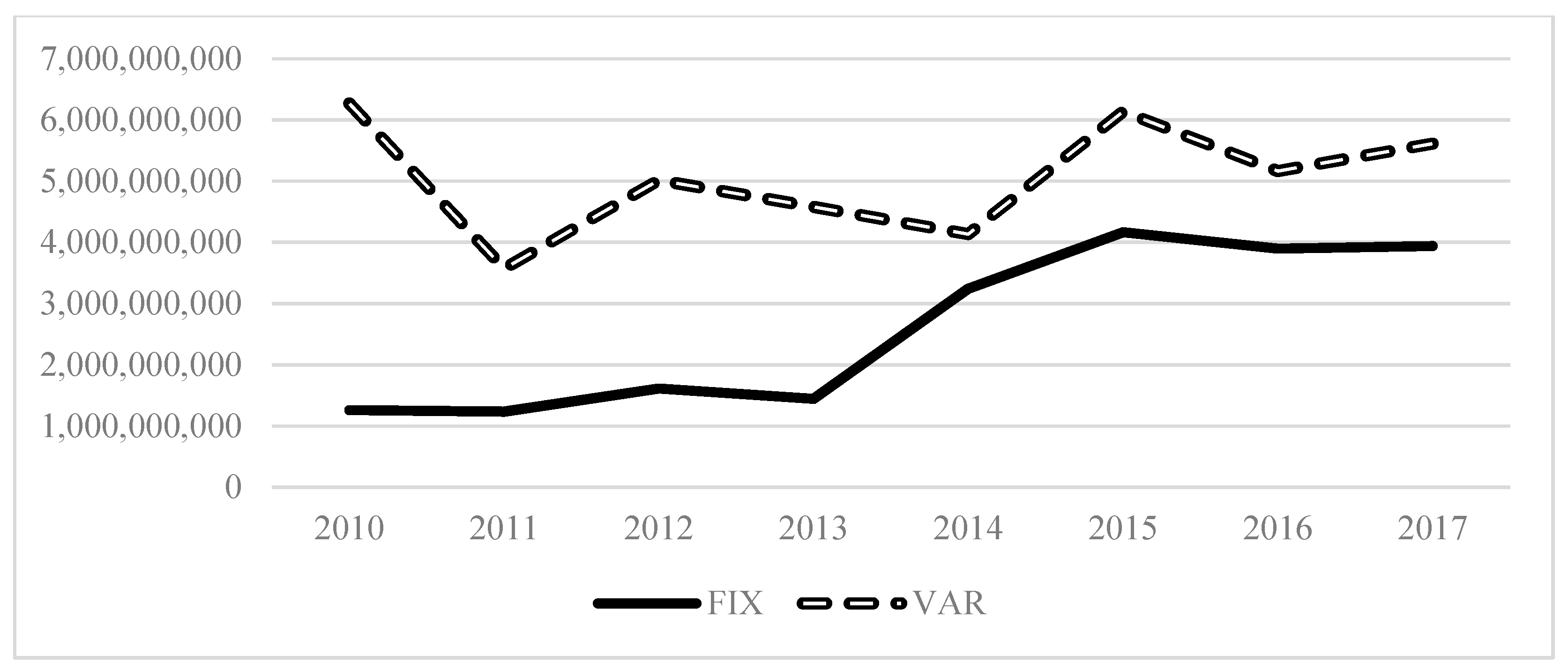

Analyzing the information disclosed in the EBA reports about the remuneration of HEs, we noticed it in order to comply with the bonus cap.

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 graphically represent the evolution of the average variables and fixed components spanning from 2010 to 2017. In

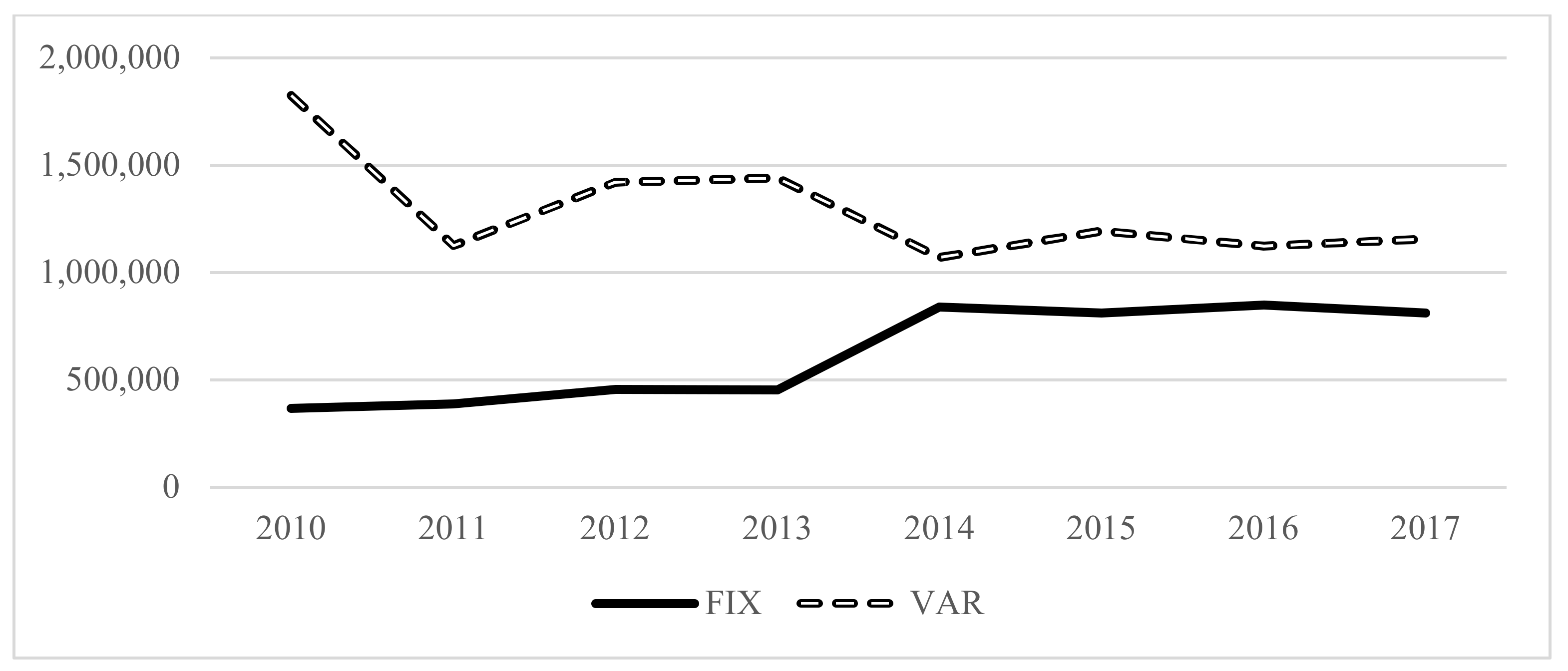

Figure 10 we observed how the variable pay diminished from 2010 to 2017 and the fixed pay literally tripled its value. However, looking at the total remuneration is a bit foggy; therefore, the data tendency by HEs was refined. Once again, the plot seemed to be a funnel in which variable and fix pays converged in 2014 (

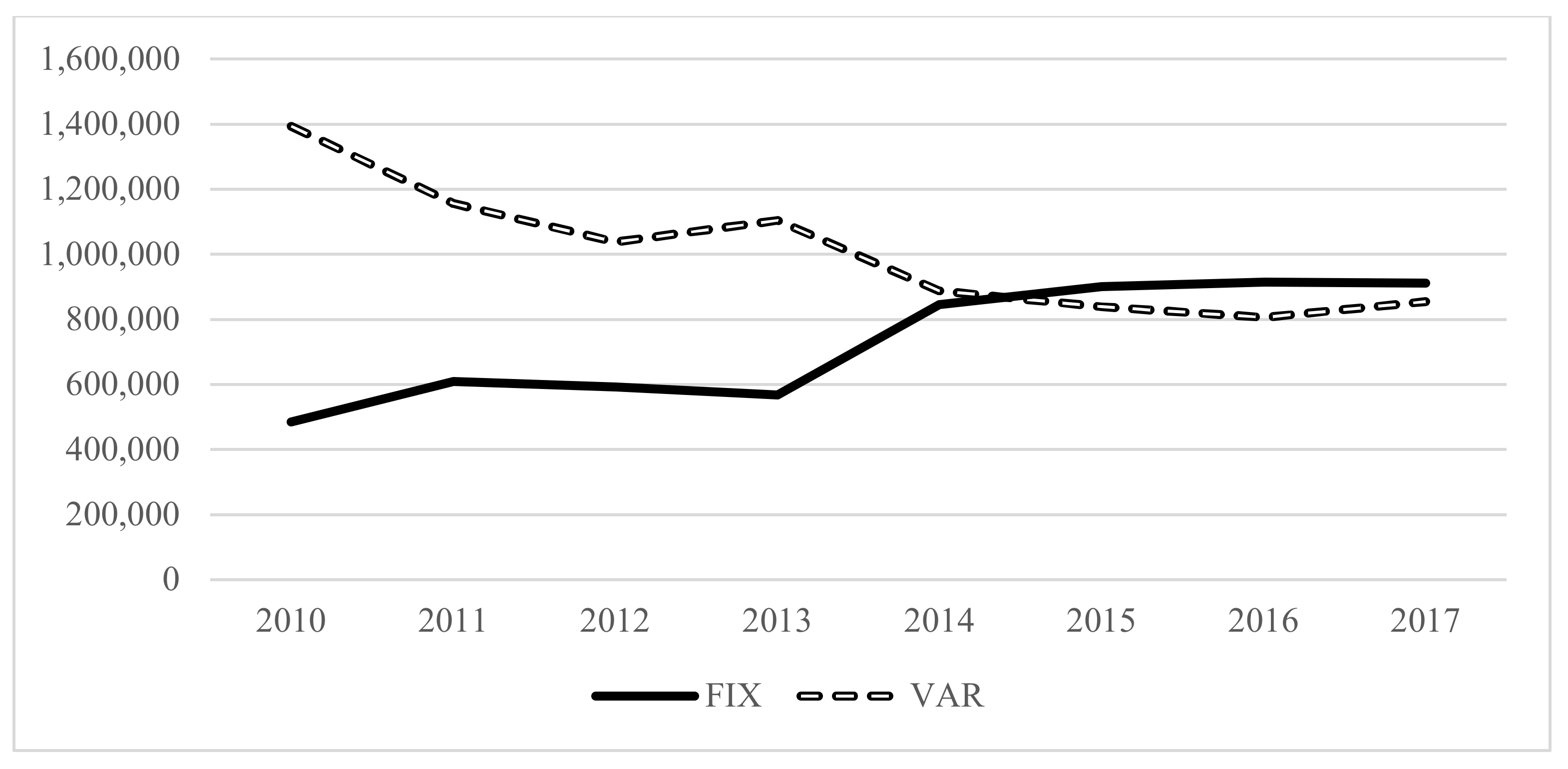

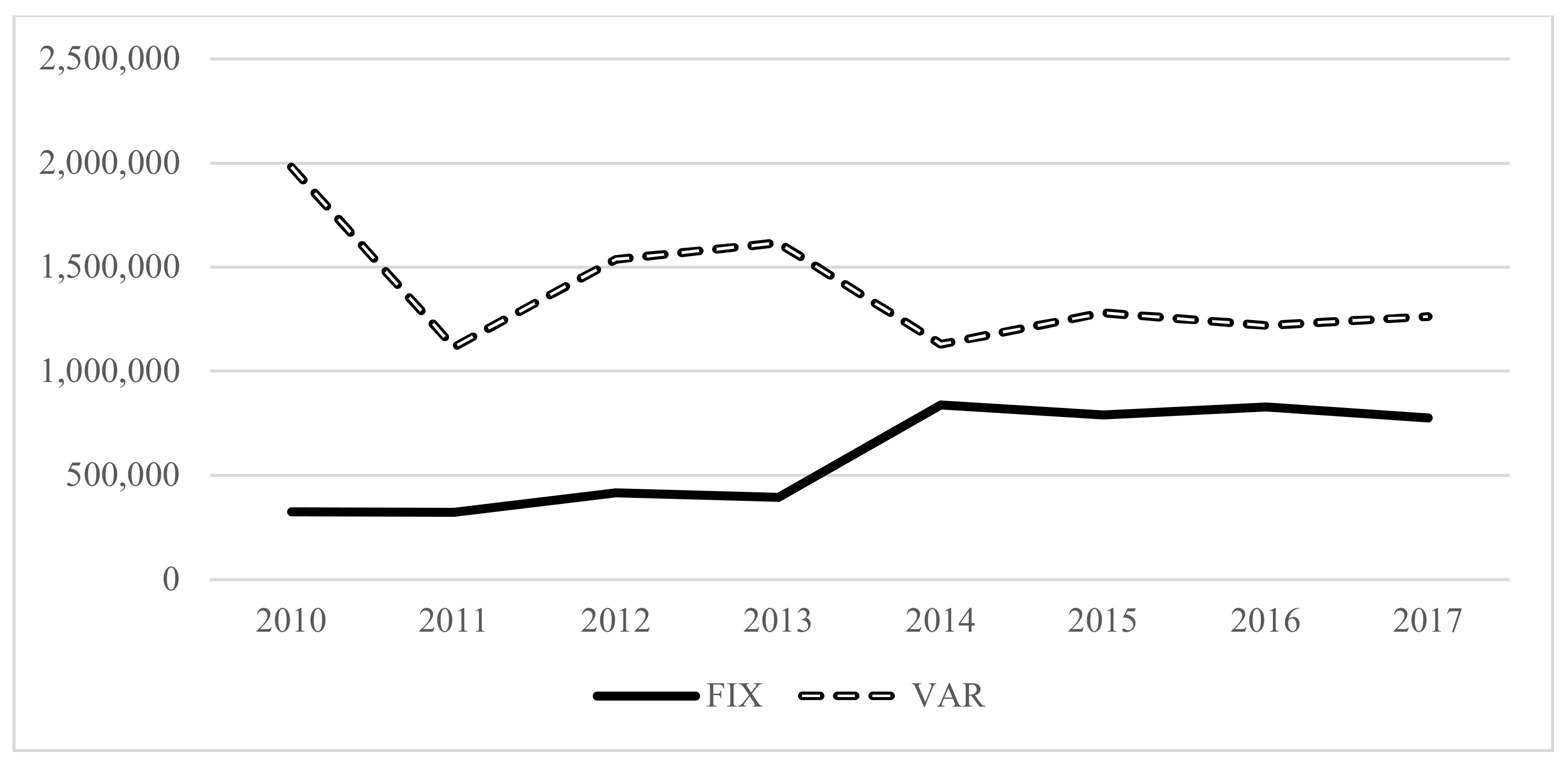

Figure 11). However, was this equal across countries? Well, on average, the amounts significantly differed between the UK and the rest of the EU countries, again.

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 show the total fixed and variable components of remuneration plans per HE in the EU (except the UK) and in the UK, respectively. The results are more than evidence; in the EU, we noticed a clear increase in fixed pay to the detriment of the variable pay. What is representative here is that at the time the bonus cap became applicable, the amount of the fixed component exceeded the bonus pay in absolute terms. This is impressive but perfectly coherent since a cap in variable pay will necessarily lead to an increase in the fixed part [

5], as said before. Moreover, unreported results indicate that more than the 50% of the fixed remuneration was paid via instruments instead of cash. Therefore, being speculative, this behavior could be a signal of the attempt of European banks to circumvent or partially avoid the new Guidelines. At the same time, UK bankers also denoted a herding behavior. As also observed before in

Figure 9,

Figure 13 demonstrates that UK bank HEs were more variable paid, and that the reduction in this component does not imply (because maybe they did not need it) an increase in the fixed pay that overpassed the variable one. Thus, British bankers appeared to continue keeping the variable remuneration up, suggesting their preference to remain in the UK in case of a Brexit scenario.

4. Earnings Management (Income Smoothing) and the New Remuneration Rules

Earnings is a proxy for accounting quality [

35]. As earnings quality is not directly observable and its various definitions may be confusing, among the existing proxies, earnings management is the most used in the empirical literature. Earnings management generally refers to the discretionary (and opportunistic) use of financial information. For instance, it consists of a situation in which managers use their judgment in shaping financial statements [

111], either to mislead other contractual parts, creating information asymmetries about the underlying financial performance of the firm, or to influence accounting numbers so as to maximize top-level managers’ remuneration [

77,

112], among others. Income smoothing is another proxy for earnings quality but is strongly related to earnings management. Income smoothing is the practice of moderating (smoothing) earnings fluctuation year after year, moving profits obtained in economic booms to poorer periods such as economic shocks [

113]. Lowering earnings volatility due to managers’ incentives may create a lack of transparency with less sustainable profits, which hurts financial stability. Therefore, in a nutshell, earnings management (income smoothing) is based on managers’ incentives to shape accounting information.

The variable and fixed remuneration flows are crucial from the bank perspective and in crisis times because changes in corporate governance actions may lead to changes in bank strategies. If the portion of variable pay to the total remuneration of bank executives diminishes, then bank flexibility reduces too. If a bank faces a financial crisis, by nature the bank has to cut its costs or expenses to recoup its competitiveness. Costs to be cut would be loan loss impairments, dividends, credit supply to avoid unnecessary risk, and of course remuneration. In relation to the last, if bank managers are paid with variable instruments, then there is no problem, however, if they are mostly paid via fixed components, then their remuneration is not tied to bank performance and thus bank survival becomes a complicated task since compensation adjustments on fixed pay are impossible. As a response, earnings management practices are likely to occur since accounting-based incentives compensation is likely to reinforce attitudes towards building countercyclical buffers (see

Table 1). Therefore, the strategies for maximizing compensation have no one-way direction (income-increasing mechanisms). “Management incentives for earnings vary depending on how accounting earnings are reflected in the incentive compensation” [

114], so remuneration schemes may also drive income-decreasing accounting procedures [

77].

The upper and lower limits of the remuneration guidelines may create accounting incentives for, at first, inefficient actions. For instance, in the lower bound, if managers intuit that they are just about losing great part of variable pay, they are encouraged to behave opportunistically, taking “bad risks” (risks that destroy bank value) to ensure the fixed pay (i.e., exercising call options at a fixed price). Oppositely, on the upper side, outstanding executives will probably reject “good risks” because any better performance does not imply higher remuneration anymore. Thus, they avoid the likelihood of injuring their pay or dragging their remuneration below their reference marks. In short, payment boundaries facilitate accounting incentives to manage earnings because the bank may lose business opportunities when rejecting good projects (assuming “good risk”). These are some arguments that may explain the repudiation of remuneration limits [

5,

61], which does not mean either eliminating compensation components that motivate earnings management or boosting those that impede such opportunistic procedures [

116].

The relationship between compensation schemes and earnings management practices has strongly drawn the attention of stakeholders. Shareholders, analysts, investors, and even auditors really care about earnings management. If a significant part of bank performance lies in earnings, managing it may provoke a false image of financial stability, moving earnings from future good times to the present bad moment (the income smoothing hypothesis). Therefore, “if the “true” performance of the firm is hidden, there is potential for less efficient resource allocation decisions” [

117], which leads to inefficient remuneration structures. As a conclusion, even though the empirical literature has gone over it, there is still need for further analyses.

How do remuneration schemes affect earnings management behavior? Well, the evidence shows that the answer remains partially inconclusive, which is more pronounced in the banking sector because of the scarce studies. Overall, management remuneration is positively associated with earnings management and income smoothing discretionary techniques [

118], but recent studies suggest that this happens when firms’ characteristics are associated with moderate levels of CEO compensation and earnings management [

119]. The argument is that excessive remuneration may attract shareholders’ attention and raises concerns among investors about the materiality of executive and shareholder returns [

120], so the use of relative income smoothing to dampen investors’ beliefs is understandable since job insecurity or maybe remuneration revisions may jeopardize management positions. In fact, Li et al. [

119] concluded that “when CEO compensation and earnings management are too high, such accounting manipulations are penalized (not rewarded).”

Salary, the fixed component of remuneration, restrains earnings management. It is obvious that salary is price-movement invariant; however, earnings management is costly (e.g., a litigation risk), so managers would have incentives to reduce this opportunistic behavior with an eye to lowering potential costs [

116].

Broadly, the variable pay is expected to positively influence earnings management practices; however, the contrary may happen, too. First, managers receiving nil bonus adopt income-decreasing accruals, in line with taking a big bath [

77,

121]. Second, a positive impact on this relation is habitual; under the variable compensation system, managers have incentives to use their maximum accounting discretion to boost earnings when latent earnings may hardly reach a minimum bonus bound and push earnings downwards if performance is too poor to create incentives [

114,

116,

121]. Third, from the income smoothing perspective, both positive and negative signs can be found. The findings of Shuto [

121] suggested that the use of discretionary accruals to smooth income enhances the link between discretionary accruals and executive bonuses, which indicates that earnings management for bonus purposes can also be treated from the efficient contracting view. Inversely, Lee and Hwang [

114] analyzed earnings management throughout using loan loss provisions and found that a higher proportion of variable compensation reduces income smoothing levels (raises earnings volatility) due to this variable pay being an incentive towards income-increasing earnings management.

Unraveling the variable payments, the empirical results are mixed. Relative to stock-based or equity-based compensation, this component primarily motivates CEOs’ rent extraction through earnings management practices [

105,

122,

123], income-increasing earnings management when financial reporting quality is low [

124], and, in the case of the banking industry, when capital ratios are closer to the minimum value required by regulators [

124]. Lee and Hwang [

114] found no evidence of equity-based compensation acting as an effective incentive to increment bank value, but rather a motive for income-increasing earnings management. The explanation lies in that equity-linked compensation would boost banks’ procyclicality [

115]. Increasing earnings raises banks’ capital ratio and eases lending attitudes, which consequently, as happened during the 2008 financial crisis, leads to more loan loss impairments. These losses (though future allowances) shrink credit supply, with fatal consequences for economic growth. The authors argue that in spite of the profits from decreasing earnings volatility (income smoothing) being insignificant in their sample consisting of Korean banks, because executives’ average tenure is short (2 to 3 years), stock-based compensation might powerfully incentivize managers to use discretion to report consistent earnings. These opposing results warn about a need to design an optimal managerial compensation contract [

99], which seems to be impractical.

Dhole et al. [

39] advocated for the term “inside-debt” in equity-linked compensation, which mitigates earnings management and lowers levels of income smoothing (it does not mean discarding certain levels of income smoothing). The idea is that managers have a natural preference for smoothing earnings because investors perceive firms with stable earnings over time to be less risky. Hence, managers that are only equity-paid (with no debt notion) will resort to this behavior. However, when a manager is paid with a fraction of a firm’s debt (and then holds inside debt), the higher the inside leverage is, the more aligned their incentives will be with those of debtholders. Therefore, managers will tend to protect inside debt value and will be more risk averse. Less risky corporate policies safeguard earnings from sharp peaks and valleys.

The link between stock-option compensation and earnings management is tricky because of the grant and exercise dates [

116,

117,

125]. Managers will try to level stock price downward (upward) before (when) options are granted (exercised), thereby appreciating stock-option value. That means earnings will be managed up before exercising stock options and managed down before stock options are granted. Accordingly, performance-vested stock options will be positively associated with earnings management that enhance the firm’s performance [

126].

In short, income smoothing practices that appear as implicit contracts are not warranted (e.g., job insecurity or compensation revision), which jeopardizes bank managers’ positions. Discretionary (opportunistic) behavior to managing earnings, and thus compensation plans, is usually seen as costly (for the fixed component) and inefficient for increasing bank value (through equity-based compensation) because it encourages procyclicality [

115]. It could be the case that the short-terminism would be behind this: If their pay is focused on short-term incentives, despite the Guidelines, bank managers have a singular financial disincentive to engage in CSR. Therefore, CSR involvement might act as a strong incentive for bank managers to not engage in opportunistic practices that hurt financial transparency.

6. Conclusions

Corporate governance (CG) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) are two sides of the same coin. Both may exist at the same time, but one is always preferable, to the detriment of the other. The new EU remuneration policy in the banking industry may be good but is not the desired CG mechanism due to its economic effects. Oppositely, investing in CSR strategies may be in detriment of some remuneration components but is adequate from a reputational perspective. Economic effects are commonly associated with rewarding greedy behavior, whereas reputational effects are supposed to act like “doing it in the right way.” However, there is a strong need to find the optimal position in such aspects [

25].

Corporate governance issues in banks considerably differ from other non-financial companies for many reasons, especially the remuneration policy. The issue of risk-taking has frequently been the focus of attention in banking literature because although banks operate in a regulated setting, bank managers have discretion to make decisions that significantly alter the riskiness of their financial institutions, and one branch using discretion is the choice of setting up the level and composition of CEO compensation. Bank executives’ remuneration has general implications for the risk-taking behavior of CEOs and for banks’ performance. This is of the special concern since during financial crises moral hazard and information asymmetry problems, combined with managerial discretion, tend to be exacerbated.

With the aim of safeguarding financial stability and aligning the interests of at least stockholders with those of bank managers so as to prevent potential systemic collapses and guarantee financial system sustainability, the EU decided to regulate bank compensation policies. The result is a comprehensive set of remuneration standards that attempts to refrain excessive risk-taking by bank executives, but this time these compensation rules were amended under the regulatory rather than the supervisory perspective, so, in terms of lobbying, regulators and supervisors are not only more involved in banking activity and corporate governance but also have gained power as stakeholders. In fact, part of the compensation proposal is based on prudential oversight. Basically, among all the remuneration reforms we can highlight two main compensation mechanisms that pursue mainly aligning bank managers’ risk appetite to variable payment: (i) changes in payments via instruments and deferrals, and also giving importance to retention periods (malus and clawback), and (ii) stablishing a frontier on variable compensation (the bonus cap). Many changes to the bank risk alignment process necessarily lead to reworking risk management assessment in banks. However, intricate quantitative and qualitative criteria to evaluate bank risk may generate “hidden” compensation practices that lower the transparency of remuneration rules and accelerate the disinterest of bank managers and owners in the aftermath of bank failures and the resultant systemic risk. With respect to the bonus cap, we might almost surely say that implementing a limit on variable pay is questionable and might provide abnormal incentives and disincentives. On the one hand, more complex compensation schemes and risk management assessment disincentivize economic actors to be involved in bank discipline. In turn, based on the data that stems from the EBA reports, increasing fixed pay also disincentivizes bank discipline since poor performers are not penalized. On the other hand, the incentive compensation may influence not only the banks’ risk-taking behavior but also have an impact on their earnings management, concretely on their income smoothing practices, in spite of scarce evidence in the EU context. Although underperforming managers might take “bad risks,” high performers would reject “good risks,” thus delaying good decision-making that would have increased current profits for the following years. In addition, restrictions in variable remuneration introduced by the EBA Guidelines and CRD IV intensify the adverse selection problem in the EU neighborhood. For instance, EU banks will be attractive to the worst managers, whereas the best ones will move to countries where their efforts are compensated and not regulated downwards, such as the UK in the case of Brexit.

In this study, numerous unintended consequences were exposed, different actions were said to circumvent sound compensation practices regarding those who are material risk takers (identified staff), and, of course, several competing theories were postulated to enhance executive compensation as an important corporate governance mechanism. However, something is missing. The new EU remuneration policy may be gaming the system. The compensation rules are perceived to be controversial, which denotes that they might be driven by the political desire to calm down the excited public (voters) rather than rational and intelligent decisions that reduce information asymmetries and appease the potential migration of the scarce but best bank performers. Moreover, regulatory changes in the remuneration field such as binding bonus caps or shareholders’ say-on-pay rights, which shows that one size does not fit all, may not reinforce the banking sector, but rather create CEO incentives to discretion.

Maybe the solution for such questionable or controversial measures would be to encourage banks to engage more in CSR practices, which probably automatically rectify or balance potential problems coming from remuneration schemes. CSR in banks reshapes transparency, corporate accountability, and public trust, as well as permits banks to retain high-quality employees and facilitates financing access. It is true that CSR disclosing reduces total and cash-based compensation of top-level bank managers but favors the use of equity-based remuneration, which is associated with long-term performance incentives that control for risk appetite in the short term. CSR must be interpreted as a reputational effect that seeks to reduce conflicts of interest among all the stakeholders. In addition, CSR implication might represent a decisive incentive for bank managers to avoid discretionary behaviors that threaten financial transparency.

Several future research questions come to light. The timeline of remuneration rules has been abrupt and long (but endless), and the FSB’s proposals were drafted under an international perspective that leaves room for country-specific regulation. As the international accounting standard setters pursue the harmonization of accounting rules, it would be interesting to shed light on the convergence of the bank remuneration policy across countries, especially in the European context. Therefore, further studies should include the effect of institutional environment on the relation between remuneration structures and CEOs’ incentives to discretion. Shareholders’ approval to increase the variable-to-fixed pay ratio from 100% to 200% is in force, but what drives such an increment? It would also be of interest to analyze how government and prudential regulators pressure bank managers to use discretion or how they generate incentives via remuneration. This is of relevance since excessive risk-taking or capping bonus pay may generate large social costs and shocks for the whole economic system. Last but not least, CSR reporting is supposed to be a moderating factor in the new EU remuneration policy. Regarding the scarce banking literature on that, there is a need to examine the effect of CSR disclosure on the degree of corporate governance mechanisms (compensation in particular) in financial institutions, a sector that is powerfully monitored due to its potential social consequences. It is likely that, in the remuneration area, CSR investment (non-financial information) performs as a substitute of CG regulation (financial information).