Communicating Sustainability to Ethnocentric Consumers in China: Focusing on Social Distance from Foreign Corporations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

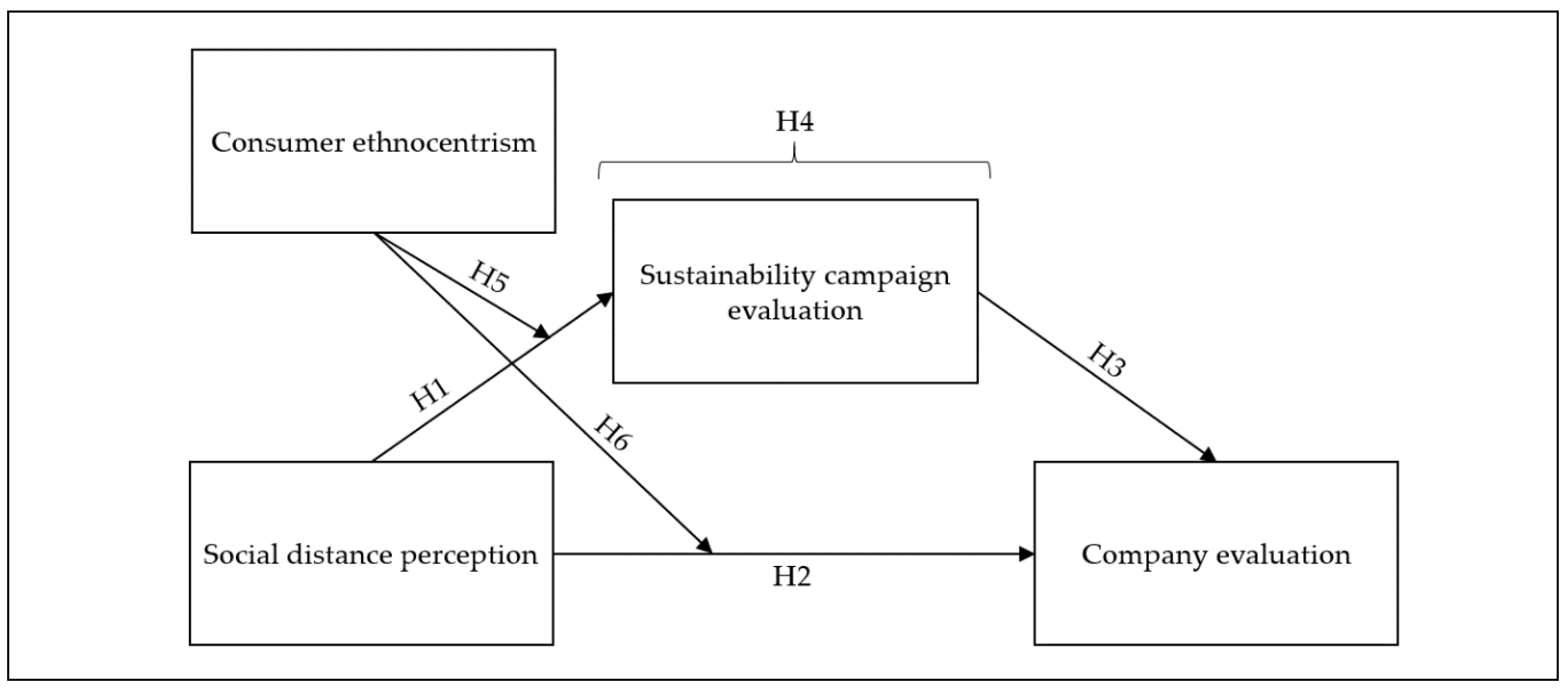

2.1. The Mediating Role of Sustainability Campaign Initiatives between Social Distance and Company Evaluations

2.2. The Moderating Role of Consumer Ethnocentrism

2.3. Social Distance and Construal Level Theory

3. Methods

3.1. Sampling and Participants

3.2. Design and Procedure

3.3. Message Design

3.4. Manipulation Check

3.5. Operational Definitions

3.5.1. Social Distance Perception

3.5.2. Consumer Ethnocentrism

3.5.3. Company Evaluations

3.5.4. Sustainability Campaign Evaluations

4. Results

4.1. Hypothesis 1–Hypothesis 6

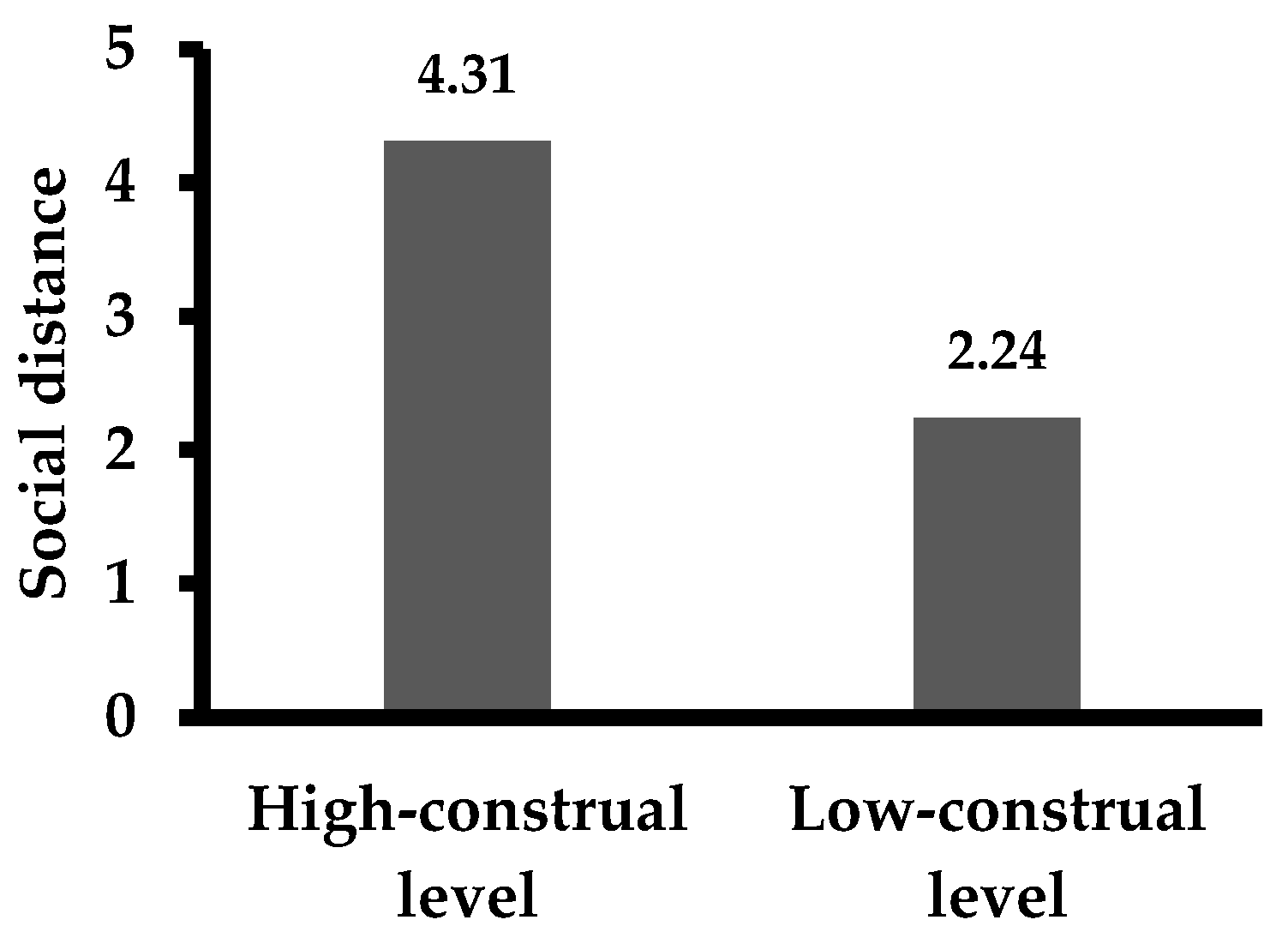

4.2. Hypothesis 7

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quartz. Available online: https://qz.com/923761/a-history-of-china-retaliating-against-foreign-companies-carrefour-toyota-honda-kfc-lotte/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Froese, F.J.; Sutherland, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y. Challenges for foreign companies in China: Implications for research and practice. Asian Bus. Manag. 2019, 18, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Daily. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2016-05/17/content_25324074.htm (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Kolk, A.; Hong, P.; van Dolen, W. Corporate social responsibility in China: An analysis of domestic and foreign retailers’ sustainability dimensions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2010, 19, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokas, K.; Yadav, K. Foreign ownership and corporate social responsibility: The case of an emerging market. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y.; Wakslak, C. Construal level theory and consumer behavior. J. Consum. Psycho. 2007, 17, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. Attitudes and attraction. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 4, 35–89. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. Social contagion and innovation: Cohesion versus structural equivalence. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 1287–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, M.J.; Flanagin, A.J. Credibility and trust of information in online environments: The use of cognitive heuristics. J. Pragmat. 2013, 59, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Á.; Dovidio, J.F.; Huici, C.; Gaertner, S.L.; Cuadrado, I. The other side of we: When outgroup members express common identity. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 1613–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, M.; Friedkin, N.E. The distant core: Social solidarity, social distance and interpersonal ties in core–periphery structures. Soc. Netw. 2001, 23, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, N.R.; Johnson, E.J.; Croson, R.T. Let’s get personal: An international examination of the influence of communication, culture and social distance on other regarding preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 60, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.S.; Wu, K.W.; Ding, M.C. Doing good does good? Sustainable marketing of CSR and consumer evaluations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2013, 20, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumasjan, A.; Strobel, M.; Welpe, I. Ethical leadership evaluations after moral transgression: Social distance makes the difference. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, J.; Bager, S.; Meyfroidt, P.; Newig, J.; Challies, E. Environmental governance of China’s belt and road initiative. Environ. Policy. Gov. 2020, 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.T.; Eden, L.; Miller, S.R. Multinationals and corporate social responsibility in host countries: Does distance matter? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, D.; Ni, N.; Jiang, Y. Do-no-harm versus do-good social responsibility: Attributional thinking and the liability of foreignness. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1316–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, M.; Wu, L. Overcoming the liability of foreignness in international retailing: A consumer perspective. J. Int. Manag. 2015, 21, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, L.; Miller, S.R. Distance matters: Liability of foreignness, institutional distance and ownership strategy. Adv. Int. Manag. 2003, 16, 187–221. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Gürhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W. Importance of corporate image for domestic brands moderated by consumer ethnocentrism. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2019, 29, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, S.; Said, M.; Siswono, S.; Firmansyah, D.A. Customer trust through green corporate image, green marketing strategy, and social responsibility: A case study. Eur. Res. Stud. 2019, 22, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.S.; Cho, Y.N.; Ko, E.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, K.H.; Sarkees, M.E. Corporate sustainability efforts and e-WOM intentions in social platforms. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 38, 1224–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, A.; Blair, S. When sustainability is not a liability: The halo effect of marketplace morality. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.M.; Lee, J.K.; Ferle, C.L. Does place matter when shopping online? Perceptions of similarity and familiarity as indicators of psychological distance. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 10, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Barnes, B.R.; Talias, M.A. Exporter–importer relationship quality: The inhibiting role of uncertainty, distance, and conflict. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1982, 33, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T.A.; Sharma, S. Consumer ethnocentrism: Construction and validation of the CETSCALE. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.S. Chinese products for Chinese people? Consumer ethnocentrism in China. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. 2017, 45, 550–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsaran-Fowdar, R.R. Are males and elderly people more consumer ethnocentric. World J. Manag. 2010, 2, 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Supphellen, M.; Grønhaug, K. Building foreign brand personalities in Russia: The moderating effect of consumer ethnocentrism. Int. J. Advert. 2003, 22, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liviatan, I.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Interpersonal similarity as a social distance dimension: Implications for perception of others’ actions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 1256–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Henderson, M.D.; Eng, J.; Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Spatial distance and mental construal of social events. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N.; Förster, J. Distancing from experienced self: How global-versus-local perception affects estimation of psychological distance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, E.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y. The effects of time perspective and level of construal on social distance. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosmayer, D.C.; Fuljahn, A. Consumer perceptions of cause related marketing campaigns. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S.; Lord, K.R. Comparative and noncomparative advertising: Attitudinal effects under cognitive and affective involvement conditions. J. Advert. 1994, 23, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, G.J. Death to dichotomizing. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shentu, Y.; Xie, M. A note on dichotomization of continuous response variable in the presence of contamination and model misspecification. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 2200–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McCrea, S.M.; Liberman, N.; Trope, Y.; Sherman, S.J. Construal level and procrastination. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakslak, C.; Trope, Y. The effect of construal level on subjective probability estimates. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libby, L.K.; Shaeffer, E.M.; Eibach, R.P. Seeing meaning in action: A bidirectional link between visual perspective and action identification level. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 138, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Xie, J. Effects of social and temporal distance on consumers’ responses to peer recommendations. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| High-level construal/ends/why | “Save the Planet” Each year, 12.7 million metric tons of plastic waste are dumped into the oceans, which is equal to a truck of garbage dumped into the oceans every minute. In total, 14% of plastic waste is collected and only 2% is reused. Experts say that at this rate, plastic waste will soon outnumber the amount of fish in the ocean. Through this campaign, our company aims to save more than 1000 sea turtles, save ¥820 billion each year, and prevent seafood toxins and air pollution from killing animals and humans. |

| Low-level construal/means/how | “Plastic-Free Tuesday” On plastic-free Tuesdays, our branches skip using plastic bags, plates, straws, and any other disposable plastic materials. We also give ¥5 discount and a stuffed sea turtle to customers who bring their tumblers and/or non-plastic containers on Tuesdays. Moreover, another ¥5 will be donated to the “Save the Sea” campaign on every plastic-free purchase. We are planning to extend this plastic-free Tuesday to plastic-free weekends, and our employees are already making it a habit inside and outside of our restaurant. |

| Direct and Total Effects | β | SE | t | R2 | LLCI/ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social distance perception → Sustainability campaign evaluations (H1) | −0.09 | 0.05 | −1.69 | 0.02 | −0.19/0.01 | |

| Social distance perception → Company evaluations (H2) | −0.13 * | 0.06 | −2.31 | 0.04 | −0.24/−0.02 | |

| Sustainability campaign evaluations → Company evaluations (H3) | 0.86 *** | 0.05 | 18.05 | 0.77/0.95 | ||

| Bootstrapped indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |||

| Bootstrap result for indirect effect (H4) | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.17 | 0.00 | ||

| Predictor | Sustainability Campaign Evaluations | Company Evaluations | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | β | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||||||

| Social distance perception | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.20 | 0.01 | −0.06 * | 0.03 | −0.11 | −0.01 | |||||

| Sustainability campaign evaluations | 0.85 *** | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.94 | |||||||||

| Social distance X Consumer ethnocentrism | −0.08 * | 0.04 | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.03 | |||||

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.78 | |||||||||||

| Conditional indirect effect | |||||||||||||

| Bootstrapped indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | ||||||||||

| Index of moderated mediation | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.1406 | −0.0194 | |||||||||

| −1 SD | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.0848 | 0.1070 | |||||||||

| M | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.1766 | −0.0036 | |||||||||

| +1 SD | −0.17 | 0.07 | −0.3357 | −0.0615 | |||||||||

| Conditional direct effect | |||||||||||||

| Effect | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI | |||||||||

| −1 SD | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.96 | −0.1056 | 0.0367 | ||||||||

| M | −0.06 * | 0.03 | −2.23 | −0.1085 | −0.0165 | ||||||||

| +1 SD | −0.08 | 0.04 | −1.85 | −0.1666 | 0.0055 | ||||||||

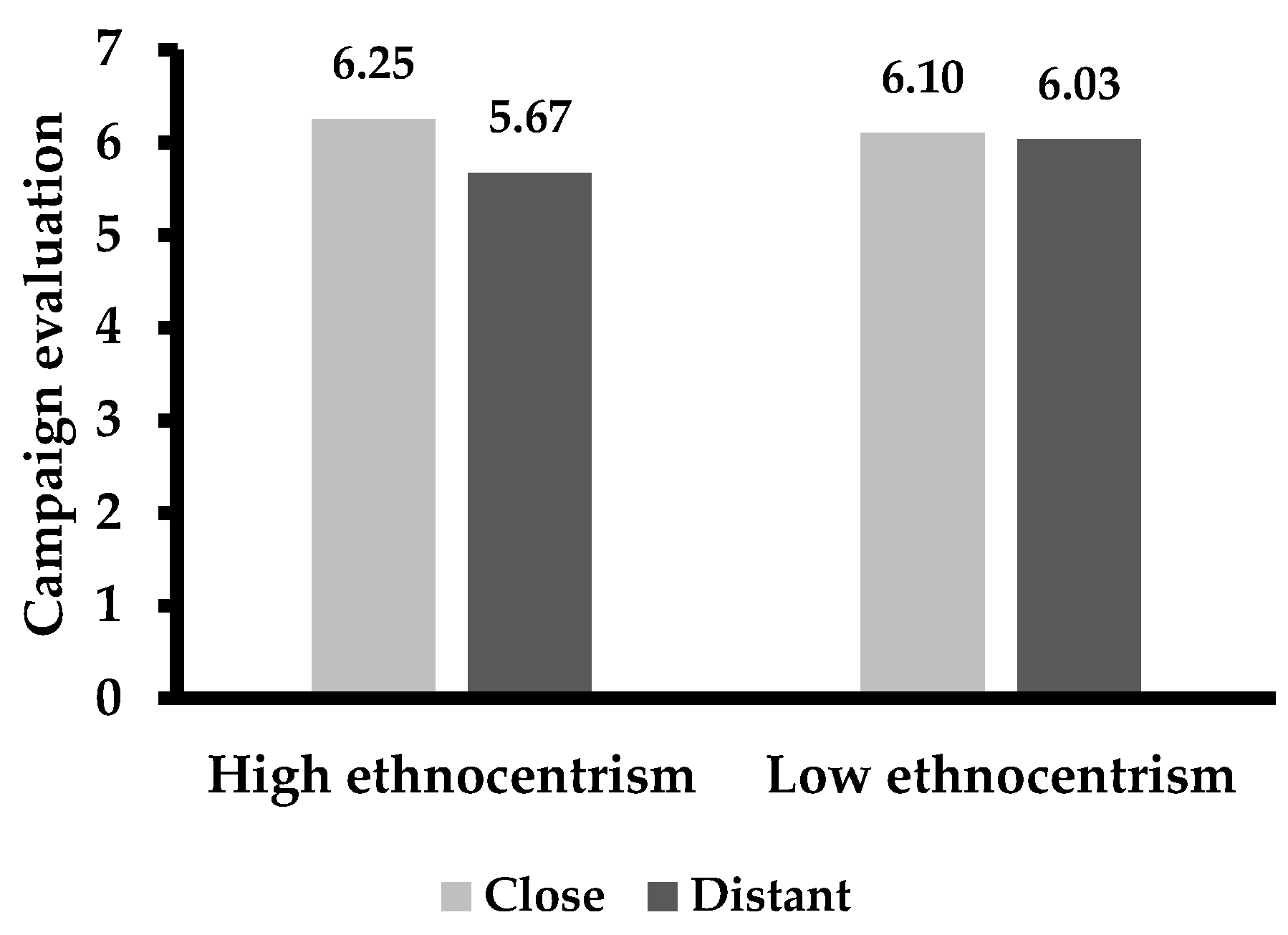

| Consumer Ethnocentrism | Social Distance | N | M | SD | ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | df | MS | F (sig.) | |||||

| High | Close | 31 | 6.25 | 0.55 | 5.04 | 1 | 5.04 | 7.52 ** |

| Distant | 30 | 5.67 | 1.03 | |||||

| Low | Close | 45 | 6.10 | 0.63 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.09 | 0.15 |

| Distant | 46 | 6.03 | 0.87 | |||||

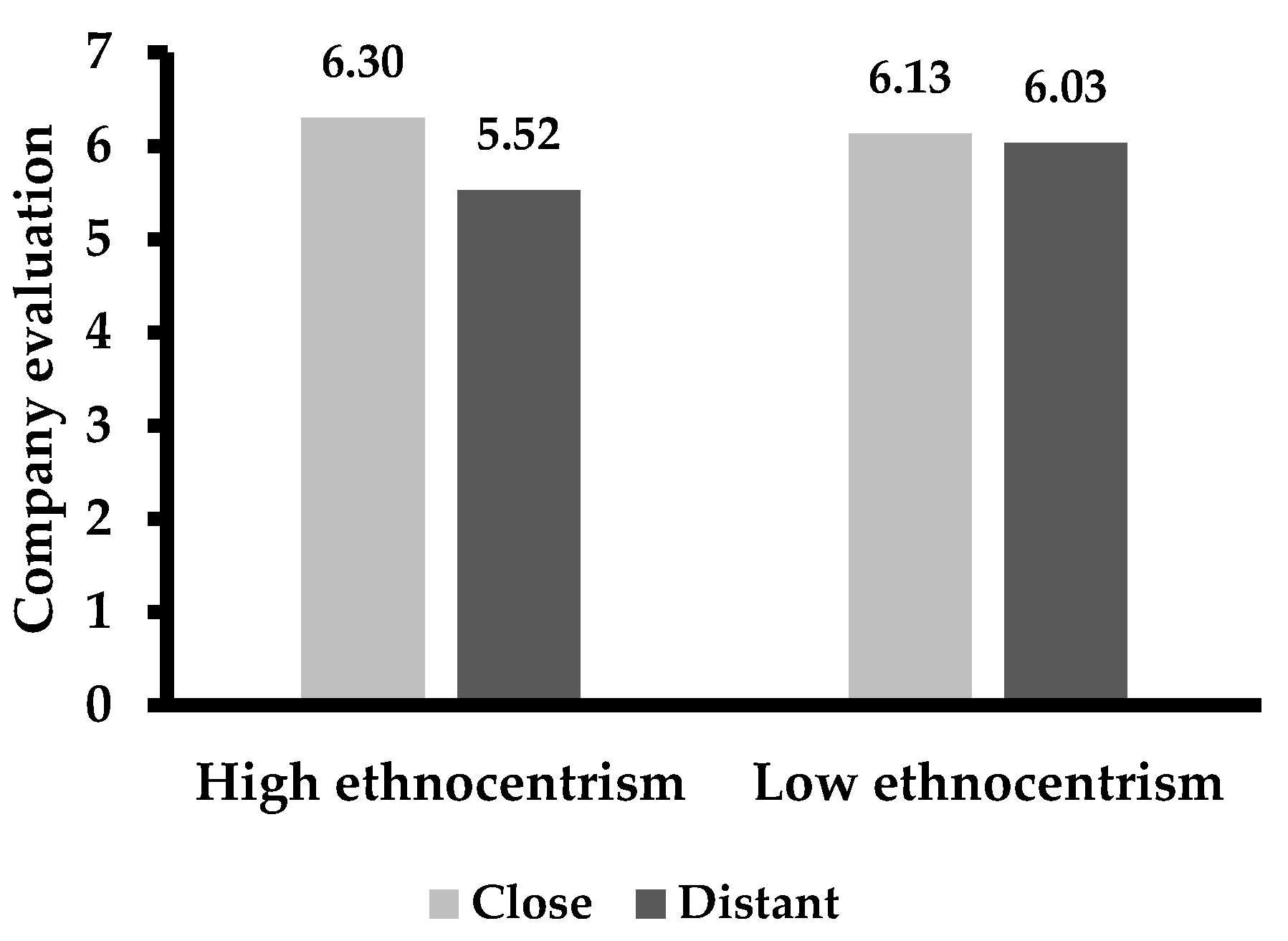

| Consumer Ethnocentrism | Social Distance | N | M | SD | ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS | df | MS | F (sig.) | |||||

| High | Close | 31 | 6.30 | 0.55 | 9.17 | 1 | 9.17 | 15.96 *** |

| Distant | 30 | 5.52 | 1.05 | |||||

| Low | Close | 45 | 6.13 | 0.59 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.39 |

| Distant | 46 | 6.03 | 0.80 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, G.; Park, H.S. Communicating Sustainability to Ethnocentric Consumers in China: Focusing on Social Distance from Foreign Corporations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010047

Park G, Park HS. Communicating Sustainability to Ethnocentric Consumers in China: Focusing on Social Distance from Foreign Corporations. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010047

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Gain, and Hyun Soon Park. 2021. "Communicating Sustainability to Ethnocentric Consumers in China: Focusing on Social Distance from Foreign Corporations" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010047

APA StylePark, G., & Park, H. S. (2021). Communicating Sustainability to Ethnocentric Consumers in China: Focusing on Social Distance from Foreign Corporations. Sustainability, 13(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010047