Development of the Circular Bioeconomy: Drivers and Indicators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Driving Forces and Relations within the Bioeconomy

2.1. Technology and Innovation

2.1.1. Advances in Biological Sciences

2.1.2. Advances in Information and Communication Technologies

2.1.3. Other Technological Advances

2.2. Market Organization

2.2.1. Advances in Horizontal and Vertical Integration

2.2.2. Globalization

2.3. Increase in Importance of Climate Change and Pressure on Ecosystems

2.4. Resource Availability

2.5. Demographics, Economic Development, and Consumer Preferences

2.6. Policies, Strategies, and Legislation

2.6.1. Global, EU and National Policies

2.6.2. Regional Policies

2.6.3. Legislation

2.7. Relations within the Bioeconomy

3. Defining and Delimiting the Bioeconomy

3.1. Definition

“The bioeconomy comprises the production of renewable biological resources and their conversion into food, feed, bio-based products, and bioenergy via innovative, efficient technologies. In this regard, it is the biological motor of a future circular economy, which is based on optimal use of resources and the production of primary raw materials from renewably sourced feedstock”[69] (p. 1)

“Sustainable, multifunctional forest management and the forest-based sector play a key role in achieving Sustainable Development Goals, for example, by providing climate action, sustaining life on land, delivering work and economic growth, enhancing responsible production and consumption, boosting industry innovation and infrastructure, creating sustainable cities and communities, enhancing good health and well-being, and providing clean energy. The bioeconomy is a key concept to boost the potential of the forest sector to deliver solutions to these multiple challenges.”[70] (p. 2)

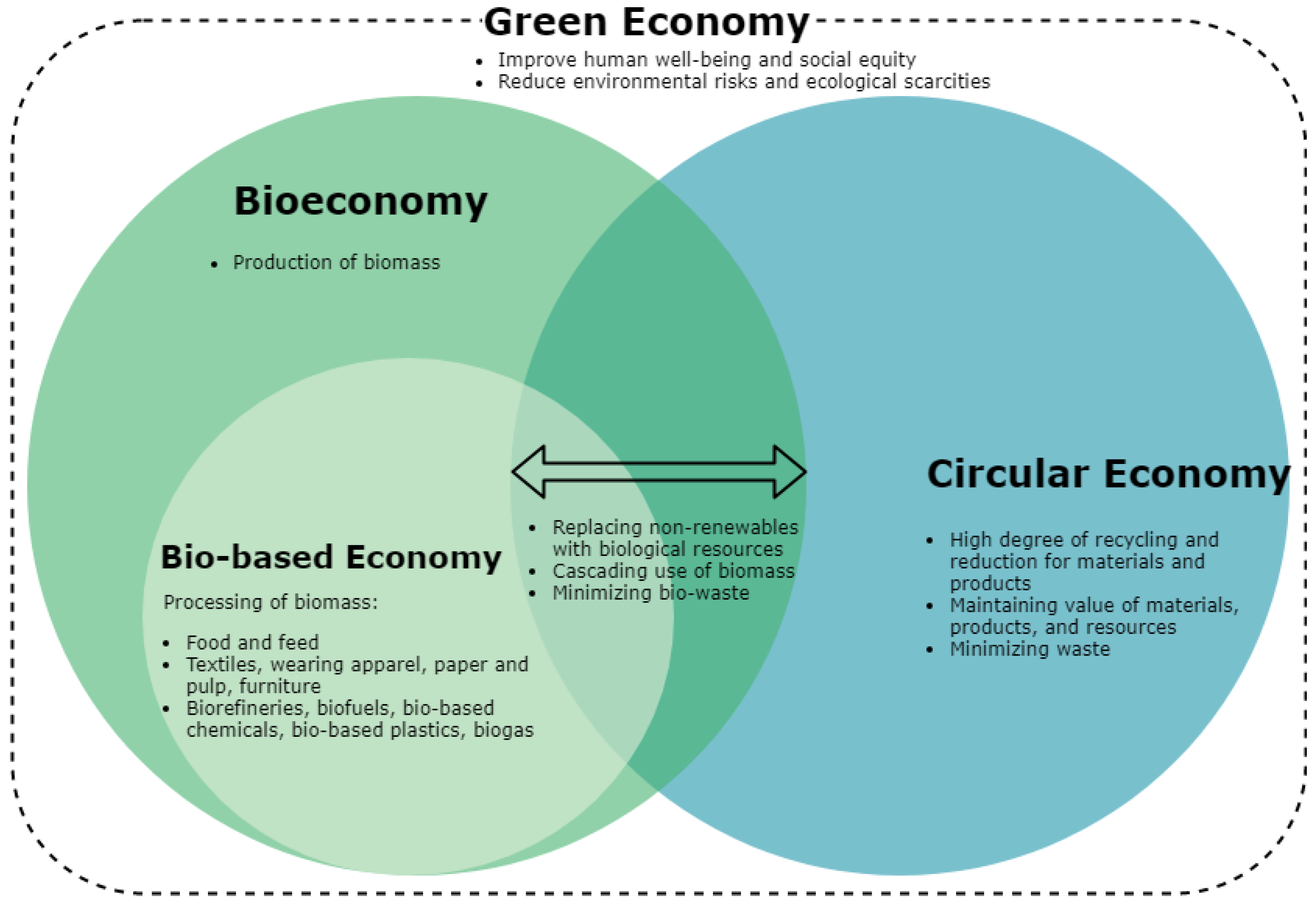

3.2. Bioeconomy, Bio-Based Economy, Green Economy, and Circular Economy

3.3. Sectors in Bioeconomy and Bio-Based Economy

4. Monitoring and Measuring the Bioeconomy

4.1. Stocktaking of Monitoring Systems

4.2. Indicators

4.3. Regulatory Challenges

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wesseler, J.; von Braun, J. Measuring the Bioeconomy: Economics and Policies. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2017, 9, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, The European Green Deal, COM/2019/640 final. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Dietz, T.; Börner, J.; Förster, J.J.; von Braun, J. Governance of the bioeconomy: A global comparative study of national bioeconomy strategies. Sustainablility 2018, 10, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy. The Position of the Bioeconomy in the Netherlands; Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–8.

- European Commission. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection between Economy, Society and the Environment. Updated Bioeconomy Strategy. 2018. ISBN 9789279941450. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52018DC0673 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Knudsen, M.T.; Hermansen, J.E.; Thostrup, L.B. Mapping Sustainability Criteria for the Bioeconomy. 2015. Available online: https://www.scar-swg-sbgb.eu/lw_resource/datapool/_items/item_25/mapping_final_20_10_2015.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Griggs, D. The Sustainable Development Goals. In Companion to Environmental Studies; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2018; pp. 725–731. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Morone, P. A New Socio-economic Indicator to Measure the Performance of Bioeconomy Sectors in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 106724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.; Wechsler, D.; Bringezu, S.; Schaldach, R. Toward a systemic monitoring of the European bioeconomy: Gaps, needs and the integration of sustainability indicators and targets for global land use. Land Use Policy 2017, 66, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivien, F.D.; Nieddu, M.; Befort, N.; Debref, R.; Giampietro, M. The Hijacking of the Bioeconomy. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, A.W.; Gillespie, I.; Hirsch, M.; Begley, C. Biosecurity and sustainability within the growing global bioeconomy. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAT-BBE. Systems Analysis Description of the Bioeconomy; SAT-BBE: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tramper, J.; Zhu, Y. Modern Biotechnology: Panacea or New Pandora’s Box? Wageningen Academic Pubishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 49, ISBN 9789086867257. [Google Scholar]

- Leopoldina, D.F.G. Wege zu Einer Wissenschaftlich Begründeten, Differenzierten Regulierung Genomeditierter Pflanzen in der EU; National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina, Union of German Academies of Sciences and the German Research Foundation: Halle, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, T. (Ed.) Applied Bioengineering; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2017; ISBN 9783527800599. [Google Scholar]

- Wesseler, J.; Zilberman, D. Biotechnology, bioeconomy, and sustainable life on land. In Transitioning to Sustainable Life on Land; Beckmann, V., Ed.; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2021; in print. [Google Scholar]

- Paarlberg, R. A dubious success: The NGO campaign against GMOs. GM Crops Food 2014, 5, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, R.D.; Blum, M.; Wesseler, J. EU member states’ voting for authorizing genetically engineered crops: A regulatory gridlock. Ger. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 64, 244–262. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, R.D.; Blum, M.; Wesseler, J. Trends in Approval Times for Genetically Engineered Crops in the United States and the European Union. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseler, J.; Smart, R.D.; Thomson, J.; Zilberman, D. Foregone benefits of important food crop improvements in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venus, T.J.; Drabik, D.; Wesseler, J. The role of a German multi-stakeholder standard for livestock products derived from non-GMO feed. Food Policy 2018, 78, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseler, J.; Politiek, H.; Zilberman, D. The Economics of Regulating New Plant Breeding Technologies-Implications for the Bioeconomy illustrated by a Survey Among Dutch Plant Breeders. Front. Plant. Sci. 2019, 10, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Laffon, J.; Kuntz, M.; Ricroch, A.E. Worldwide CRISPR patent landscape shows strong geographical biases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal Investment Plan and JTM Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_24 (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Watanabe, C.; Naveed, N.; Neittaanmäki, P. Digitalized bioeconomy: Planned obsolescence-driven circular economy enabled by Co-Evolutionary coupling. Technol. Soc. 2019, 56, 8–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Finger, R.; Huber, R.; Buchmann, N. Smart farming is key to developing sustainable agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 6148–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonucci, F.; Figorilli, S.; Costa, C.; Pallottino, F.; Raso, L.; Menesatti, P. A review on blockchain applications in the agri-food sector. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 6129–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, A. Dalla Piantagione Alla Tazzina: La Blockchain Entra nel Caffè-Blockchain 4innovation. Available online: https://www.blockchain4innovation.it/mercati/agrifood/dalla-piantagione-alla-tazzina-la-blockchain-entra-nel-caffe/ (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Provenance from Shore to Plate: Tracking Tuna on the Blockchain|Provenance. Available online: https://www.provenance.org/tracking-tuna-on-the-blockchain#overview (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Dongo, D. Blockchain Nella Filiera Alimentare, il Prototipo di Bari|GIFT. Available online: https://www.greatitalianfoodtrade.it/consum-attori/blockchain-nella-filiera-alimentare-il-prototipo-di-bari (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Näyhä, A.; Hetemäki, L.; Stern, T. New products outlook. In Future of the European Forest-Based Sector: Structural Changes Towards Bioeconomy. What Science Can Tell Us; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2014; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson, J. The wooden skyscrapers that could help to cool the planet. Nature 2017, 545, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurmekoski, E.; Jonsson, R.; Korhonen, J.; Jänis, J.; Mäkinen, M.; Leskinen, P.; Hetemäki, L. Diversification of the forest industries: Role of new wood-based products. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 1417–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Forest Products Annual Market. Review 2017–2018; Geneva Timber and Forest Study Papers; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9789210473507. [Google Scholar]

- Investopedia. Horizontal Integration. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/h/horizontalintegration.asp (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Cherubini, F. The biorefinery concept: Using biomass instead of oil for producing energy and chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BNetzA Marktstammdatenregister. Auswertung des Registers durch das ZSW Baden-Württemberg. Available online: https://www.bundesnetzagentur.de/DE/Sachgebiete/ElektrizitaetundGas/Unternehmen_Institutionen/ErneuerbareEnergien/ZahlenDatenInformationen/EEG_Registerdaten/EEG_Registerdaten_node.html;jsessionid=F68354DE8042158224AE13C9BC04E00C (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Parisi, C. Research Brief: Biorefineries distribution in the EU. Eur. Comm. Jt. Res. Cent. 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clomburg, J.M.; Crumbley, A.M.; Gonzalez, R. Industrial biomanufacturing: The future of chemical production. Science 2017, 355, aag0804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Grethe, H.; Entenmann, S.K.; Wiesmeth, M.; Blesl, M.; Wagner, M. Potential trade-offs of employing perennial biomass crops for the bioeconomy in the EU by 2050: Impacts on agricultural markets in the EU and the world. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin Institute What Is Globalization?|Globalization101. Available online: https://www.globalization101.org/what-is-globalization/ (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- Hetemäki, L.; Hurmekoski, E. Forest products market outlook. In Future of the European Forest-Based Sector: Structural Changes Towards Bioeconomy. What Science Can Tell Us; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2014; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Purnhagen, K.; Wesseler, J. EU Regulation of New Plant Breeding Technologies and Their Possible Economic Implications for the EU and Beyond. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Seidl, R.; Delzon, S.; Corona, P.; Kolström, M.; et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challinor, A.J.; Adger, W.N.; Benton, T.G. Climate risks across borders and scales. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 621–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, P.J.; Martinez de Arano, I.; Palahí, M. The bio-economy as an opportunity to tackle wildfires in Mediterranean forest ecosystems. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 86, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierling, S.; Knüpffer, E.; Behnsen, H.; Mudersbach, M.; Krieg, H.; Springer, S.; Albrecht, S.; Herrmann, C.; Endres, H.J. Bio-based plastics-A review of environmental, social and economic impact assessments. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, P.; Cardellini, G.; González-García, S.; Hurmekoski, E.; Sathre, R.; Seppälä, J.; Smyth, C.; Stern, T.; Verkerk, P.J. Substitution Effects of Wood-Based Products in Climate Change Mitigation, From Science to Policy 7. 2018. Available online: https://efi.int/sites/default/files/files/publication-bank/2019/efi_fstp_7_2018.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Spencer, W.F.; Cliath, M.M.; van den Oever, M.; Molenveld, K.; van der Zee, M.; Bos, H. Bio-Based and Biodegradable Plastics: Facts and Figures: Focus on Food Packaging in the Netherlands; Wageningen Food & Biobased Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; ISBN 9789463431217. [Google Scholar]

- Issa, I.; Delbrück, S.; Hamm, U. Bioeconomy from experts’ perspectives-Results of a global expert survey. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berkel, J.; Delahaye, R. Material Flow Monitor 2016-Technical Report Index; CBS Den Haag: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Imbert, E.; Morone, P. Exploring regional transitions to the bioeconomy using a socio-economic indicator: The case of Italy. Econ. Polit. 2020, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, M.; Klitkou, A. Socioeconomic indicators to monitor Norway’s bioeconomy in transition. Sustainablitily 2020, 12, 3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringezu, S.; Schütz, H.; Arnold, K.; Merten, F.; Kabasci, S.; Borelbach, P.; Michels, C.; Reinhardt, G.A.; Rettenmaier, N. Global implications of biomass and biofuel use in Germany-Recent trends and future scenarios for domestic and foreign agricultural land use and resulting GHG emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Braun, J. Bioeconomy-The global trend and its implications for sustainability and food security. Glob. Food Sec. 2018, 19, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgopolova, I.; Teuber, R. Consumers’ Willingness-to-pay for Health-enhancing Attributes in Food Products: A Meta-analysis. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, M.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Meeusen, M.J.G. Can bio-based attributes upgrade a brand? How partial and full use of bio-based materials affects the purchase intention of brands. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H.; Partanen, A.; Meeusen, M. Consumer perception of bio-based products-An exploratory study in 5 European countries. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, D.; Kretschmer, B.; Elbersen, B.; Panoutsou, C. Cascading use: A systematic approach to biomass beyond the energy sector. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2013, 7, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițescu, D.C.; Murgu, V. The Bioeconomy and Foreign Trade in Food Products—A Sustainable Partnership at the European Level? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAT-BBE. Evaluation of Expected Impacts and Monitoring the Trajectory of the Bioeconomy; SAT-BBE: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiropoulos, I.; Hoefnagels, R.; van den Broek, M.; Patel, M.K.; Faaij, A.P.C. The role of bioenergy and biochemicals in CO2 mitigation through the energy system-a scenario analysis for the Netherlands. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 1489–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Closing the Loop-An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; Communication From the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions A New Circular Economy Action Plan. For. A Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, M. Final Report of BERST Project. 2016. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/613671/reporting (accessed on 24 June 2016).

- Ronzon, T.; Lusser, M.; Klinkenberg, M.; Landa, L.; Sanchez Lopez, J.; M’Barek, R.; Hadjamu, G.; Belward, A.; Giuntoli, J.; Cristobal, J.; et al. Joint Research Centre Science for Policy Report: Bioeconomy Report 2016; Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bugge, M.M.; Hansen, T.; Klitkou, A. What is the bioeconomy? A review of the literature. Sustainablitily 2016, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOÖKONOMIERAT. Global Bioeconomy Summit Communiqué Global Bioeconomy Summit 2018 Innovation in the Global Bioeconomy for Sustainable and Inclusive Transformation and Wellbeing. 2018. Available online: https://gbs2018.com/fileadmin/gbs2018/GBS_2018_Report_web.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- European Bioeconomy. Alliance Bioeconomy-A Motor for the Circular Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Confederation of European Forest Owners. Private Forest Owners Call for An Ambitious Update of the EU Bioeconomy Strategy; Confederation of European Forest Owners: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, D.; Droste, N.; Allen, B.; Kettunen, M.; Lähtinen, K.; Korhonen, J.; Leskinen, P.; Matthies, B.D.; Toppinen, A. Green, circular, bio economy: A comparative analysis of sustainability avenues. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 716–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unep; ILO; UNIDO; UNDP; Unitar. Advancing an Inclusive Green Economy: Rationale and Context-Definitions for Green Economy. 2012. Available online: https://unitar.org/sites/default/files/uploads/egp/Section1/PDFs/1.3%20Definitions%20for%20Green%20Economy.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Pülzl, H.; Kleinschmit, D.; Arts, B. Bioeconomy-an emerging meta-discourse affecting forest discourses? Scand. J. For. Res. 2014, 29, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, O.; Gomez San Juan, M. How Sustainability is Addressed in Official Bioeconomy Strategies at International, National and Regional Levels: An Overview. 2016. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5998e.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Carus, M.; Dammer, L. The Circular Bioeconomy-Concepts, Opportunities, and Limitations. Ind. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Expert Group Report-Review of the EU Bioeconomy Strategy and its Action Plan; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Buongiorno, J. On the accuracy of international forest product statistics. For. An. Int. J. For. Res. 2018, 91, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy-Economic and Business Rationale for An Accelerated Transition. 2013. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- EuropaBio. Strengthening Biotechnology and the Eu Project; EuropaBio: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hetemäki, L.; Hanewinkel, M.; Muys, B.; Ollikainen, M.; Palahí, M.; Trasobares, A. Leading the Way to a European Circular Bioeconomy Strategy; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2017; Volume 5, p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Clean Planet for all-A European long-term strategic vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy. Depth Anal. Support Comm. Commun. Com 2018, 773, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Heijman, W. How big is the bio-business? Notes on measuring the size of the Dutch bio-economy. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuosmanen, T.; Kuosmanen, N.; El-Meligli, A.; Ronzon, T.; Gurria, P.; Iost, S.; M’Barek, R. How Big is the Bioeconomy? Reflections from An Economic Perspective; EUR 30167 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Efken, J.; Dirksmeyer, W.; Kreins, P.; Knecht, M. Measuring the importance of the bioeconomy in Germany: Concept and illustration. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzon, T.; Piotrowski, S.; M’Barek, R.; Carus, M. A systematic approach to understanding and quantifying the EU’s bioeconomy. Bio-Based Appl. Econ. 2017, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzon, T.; Piotrowski, S.; M’barek, R.; Carus, M.; Tamošiūnas, S. Job and Wealth in the EU Bioeconomy. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/89h/7d7d5481-2d02-4b36-8e79-697b04fa4278 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Fumagalli, S.; Trenti, S. A First Attempt to Measure the Bio-Based Economy. 2014. Available online: https://group.intesasanpaolo.com/content/dam/portalgroup/repository-documenti/public/Contenuti/RISORSE/Documenti%20PDF/en_sostenibilita/CNT-05-000000023F746.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Lier, M.; Aarne, M.; Kärkkäinen, L.; Korhonen, K.T.; Yli-Viikari, A.; Packalen, T. Synthesis on Bioeconomy Monitoring Systems in the EU Member States-Indicators for Monitoring the Progress of Bioeconomy; Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke): Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski, S.; Carus, M.; Carrez, D. European Bioeconomy in Figures. Available online: www.biconsortium.eu (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Robert, N.; Giuntoli, J.; Araujo, R.; Avraamides, M.; Balzi, E.; Barredo, J.I.; Baruth, B.; Becker, W.; Borzacchiello, M.T.; Bulgheroni, C.; et al. Development of a bioeconomy monitoring framework for the European Union: An integrative and collaborative approach. New Biotechnol. 2020, 59, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracco, S.; Calicioglu, O.; Juan, M.G.S.; Flammini, A.; Gomez San Juan, M.; Flammini, A. Assessing the contribution of bioeconomy to the total economy: A review of national frameworks. Sustainablility 2018, 10, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesters, K.P.H.; van Dam, J.E.G.; Bos, H.L. Protocol Monitoring Materiaalstromen Biobased Economie; Wageningen UR Food Biobased Res: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Linser, S.; Lier, M. The contribution of sustainable development goals and forest-related indicators to national bioeconomy progress monitoring. Sustainablility 2020, 12, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, S.; Wesseler, J.; Kardung, M.; Van Leeuwen, M.; Van Meijl, H.; Costenoble, O.; Vrins, M.; De Groot, T.; Jansen, K. First Stakeholder Workshop-D7.2. 2019. Available online: http://biomonitor.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/D7.2_First-Stakeholder-Workshop.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- BERST. Criteria and Indicators Describing the Regional Bioeconomy. 2014. Available online: https://www.wecr.wur.nl/BerstPublications/D1.1%20Criteria%20and%20Indicators%20describing%20Regional%20Bioeconomy%20(Oct%202014).pdf (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Eurostat. Sustainable Development in the European Union—Monitoring Report on Progress Towards the SDGs in An EU Context—2019 Edition. 2019. ISBN 978-92-76-00777-7. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/KS-02-19-165 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Ronzon, T.; Sanjuán, A.I. Friends or foes? A compatibility assessment of bioeconomy-related Sustainable Development Goals for European policy coherence. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 119832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracco, S.; Tani, A.; Çalıcıoğlu, Ö.; Gomez San Juan, M.; Bogdanski, A. Indicators to Monitor and Evaluate the Sustainability of Bioeconomy. Overview and A Proposed Way Forward; FAO Environment and Natural Resource Management Working Paper: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Philippidis, G.; Bartelings, H.; Smeets, E. Sailing into Unchartered Waters: Plotting a Course for EU Bio-Based Sectors. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 147, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmetzer, S.; Lask, J.; Vargas-Carpintero, R.; Pyka, A. Learning to change: Transformative knowledge for building a sustainable bioeconomy. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 167, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Declaration of the World Summit on Food Security; WSFS: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolini, F.; Gava, O.; Brunori, G. Biogas and EU’s 2020 targets: Evidence from a regional case study in Italy. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseler, J.; Scatasta, S.; Nillesen, E. The Maximum Incremental Social Tolerable Irreversible Costs (MISTICs) and other benefits and costs of introducing transgenic maize in the EU-15. Pedobiologia 2007, 51, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Torralba, M.; Hartel, T.; Fagerholm, N. Perceived ecosystem services synergies, trade-offs, and bundles in European high nature value farming landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1565–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohbach, M.W.; Kohler, M.L.; Dauber, J.; Klimek, S. High Nature Value farming: From indication to conservation. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 57, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikard, H.-P.; Punt, M.; Wesseler, J. Diversity measurement combining relative abundances and taxonomic distinctiveness of species. Divers. Distrib. 2006, 12, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jander, W.; Grundmann, P. Monitoring the transition towards a bioeconomy: A general framework and a specific indicator. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, C.; Wesseler, J.H.H. A comparison of the EU and US regulatory frameworks for the active substance registration of microbial biological control agents. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbà, C.; Chinnici, G.; D’Amico, M. Novel Food: The Impact of Innovation on the Paths of the Traditional Food Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Drabik, D.; Heerink, N.; Wesseler, J. Getting an Imported GM Crop Approved in China. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purnhagen, K.P.; Wesseler, J.H.H. Maximum vs minimum harmonization: What to expect from the institutional and legal battles in the EU on gene editing technologies. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2310–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, D.; Kershen, D.; Nepomuceno, A.; Pogson, B.J.; Prieto, H.; Purnhagen, K.; Smyth, S.; Wesseler, J.; Whelan, A. A comparison of the EU regulatory approach to directed mutagenesis with that of other jurisdictions, consequences for international trade and potential steps forward. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1673–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesseler, J.; Zhao, J. Real Options and Environmental Policies: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Azar, P.D. Endogenous Production Networks. Econometrica 2020, 88, 33–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jander, W.; Wydra, S.; Wackerbauer, J.; Grundmann, P.; Piotrowski, S. Monitoring bioeconomy transitions with economic-environmental and innovation indicators: Addressing data gaps in the short term. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, D.T. Empirics for economic growth and convergence. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1996, 40, 1353–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghini, A. Evolution of trade patterns in the new EU member states. Econ. Transit. 2005, 13, 629–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NACE | Fumagalli and Trenti [87] | SAT-BBE [60] | Efken et al. [84] | Ronzon et al. [86] | Piotrowski et al. [89] | Ronzon et al. [85] | Our FRAMEWORK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A01 | Crop and animal production, hunting and related service activities | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| A02 | Forestry and logging | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| A03 | Fishing and aquaculture | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| C10 | Manufacture of food | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C11 | Manufacture of beverages | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C12 | Manufacture of tobacco | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C13 | Manufacture of textiles | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C14 | Manufacture of wearing apparel | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C15 | Manufacture of leather and related products | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C16 | Manufacture of wood and products of wood and cork, except furniture; manufacture of articles of straw and plaiting materials | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C17 | Manufacture of paper and paper products | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C19 | Manufacture of coke and refined petroleum products | X | ✓ | X | X | X | X | ✓✓ |

| C20 | Manufacture of chemicals and chemical products | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C21 | Manufacture of basic pharmaceutical products and pharmaceutical preparations | X | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C22 | Manufacture of rubber and plastic products | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| C31 | Manufacture of furniture | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| D35 | Electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ | X | ✓✓ |

| D3511 | Production of electricity | X | ✓ | X | X | X | ✓ | ✓✓ |

| E36 | Water collection, treatment, and supply | X | X | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| E37 | Sewerage | X | X | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| E38 | Waste collection, treatment, and disposal activities; materials recovery | X | X | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| E39 | Remediation activities and other waste management services | X | X | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| F41 | Construction of buildings | X | ✓ | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| F42 | Civil engineering | X | ✓ | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| G46 | Wholesale trade, except for motor vehicles and motorcycles | X | X | ✓ | X | X | X | ✓ |

| G47 | Retail trade, except for motor vehicles and motorcycles | X | X | ✓ | X | X | X | ✓ |

| H | Transportation and storage | X | X | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| I55 | Accommodation | X | X | ✓ | X | X | X | ✓ |

| I56 | Food and beverage service activities | X | X | ✓ | X | X | X | ✓ |

| M7211 | Research and experimental development on biotechnology | X | X | X | X | X | X | ✓✓ |

| R9104 | Botanical and zoological gardens and nature reserves activities | X | X | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

| Main Indicator | Rationale | Sustainability Dimension | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Food and nutrition security | |||

| Availability of food | To assess the contribution of the bioeconomy to food and nutrion security based on the widely accepted four dimension of food security | Society | FAO [101] |

| Access to food | |||

| Utilization | |||

| Stability | |||

| 2. Sustainable natural resource management | |||

| Sustainability threshold levels for Bioeconomy Technologies | New indicator based on genuine investment theory with a focus on the bio-based economy | Environment | Own elaboration, Bartolini et al. [102], Wesseler et al. [103] |

| Biodiversity | Indispensable to assess the impact of biomass production at the genetic, species, and ecosystem level | Environment | SAT-BBE [12], Bartolini et al. [102], Plieninger et al. [104], Strohbach et al. [105], Weikard et al. [106] |

| Land cover | To assess land use conflicts | Environment | Lier et al. [88] |

| Primary Biomass production | To assess biomass availability | Economy | BERST [95] |

| Sustainable resource use | To assess the sustainability of biomass production | Environment | Lier et al. [88] |

| 3. Dependence on non-renewable resources | |||

| Bio-energy replacing non-renewable energy | To assess the direct substitutability of fossil resources with biological resources | Environment | Own elaboration |

| Bio-material replacing non-renewable resources | To assess the direct substitutability of fossil resources with biological resources | Environment | Lier et al. [88] |

| Biomass self-sufficiency rate | To assess independence from biomass imports. | Economy | Own elaboration |

| Material use efficiency | To assess the degree of circularity | Economy | Lier et al. [88] |

| Certified bio-based products | To assess the variety of products from bio-based production. | Environment | Own elaboration |

| 4. Mitigating and adapting to climate change | |||

| Greenhouse gas emissions | Traditional indicator applied to bioeconomy sectors | Environment | EUROSTAT [96] |

| Climate footprint | To assess CO2 emissions for sectors based on life cycle assessments of bio-based production | Environment | Own elaboration |

| Climate change adaptation | More indicators of adaption to climate change impacts are needed. | Environment | Own elaboration |

| 5. Employment and economic competitiveness | |||

| Innovation | Traditional indicator applied in more sectorial and spatial detail | Economy | Lier et al. [88]; SAT-BBE [12]; Own elaboration |

| Investments | To assess biomass flows within the EU between the rest of the world | Economy | Lier et al. [88] Bartolini et al. [102] |

| Value Added of the bioeconomy sectors | To assess product uptake of bio-based production | Economy | Lier et al. [88] |

| Comparative advantage | To assess biomass flows within the EU between the rest of the world | Economy | Own elaboration |

| Production and consumption of non-food and feed bio-based products | Traditional indicator applied in more sectorial and spatial detail | Economy | Own elaboration |

| Import and export of bioeconomy raw materials and products | To assess biomass flows within the EU between the rest of the world | Economy | Own elaboration |

| Employment | Traditional indicator applied in more sectorial and spatial detail | Society | Lier et al. [88] |

| Bioeconomy-driving Policies | To assess policies, strategies, and legislation on the bioeconomy | Society | Own elaboration |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kardung, M.; Cingiz, K.; Costenoble, O.; Delahaye, R.; Heijman, W.; Lovrić, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; M’Barek, R.; van Meijl, H.; Piotrowski, S.; et al. Development of the Circular Bioeconomy: Drivers and Indicators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010413

Kardung M, Cingiz K, Costenoble O, Delahaye R, Heijman W, Lovrić M, van Leeuwen M, M’Barek R, van Meijl H, Piotrowski S, et al. Development of the Circular Bioeconomy: Drivers and Indicators. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010413

Chicago/Turabian StyleKardung, Maximilian, Kutay Cingiz, Ortwin Costenoble, Roel Delahaye, Wim Heijman, Marko Lovrić, Myrna van Leeuwen, Robert M’Barek, Hans van Meijl, Stephan Piotrowski, and et al. 2021. "Development of the Circular Bioeconomy: Drivers and Indicators" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010413

APA StyleKardung, M., Cingiz, K., Costenoble, O., Delahaye, R., Heijman, W., Lovrić, M., van Leeuwen, M., M’Barek, R., van Meijl, H., Piotrowski, S., Ronzon, T., Sauer, J., Verhoog, D., Verkerk, P. J., Vrachioli, M., Wesseler, J. H. H., & Zhu, B. X. (2021). Development of the Circular Bioeconomy: Drivers and Indicators. Sustainability, 13(1), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010413