Big Data Analysis of Korean Travelers’ Behavior in the Post-COVID-19 Era

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourists Motivation and Behavior

2.2. Solo Travel

2.3. Group Tour

2.4. Social Network Analysis

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Manifest Content Analysis

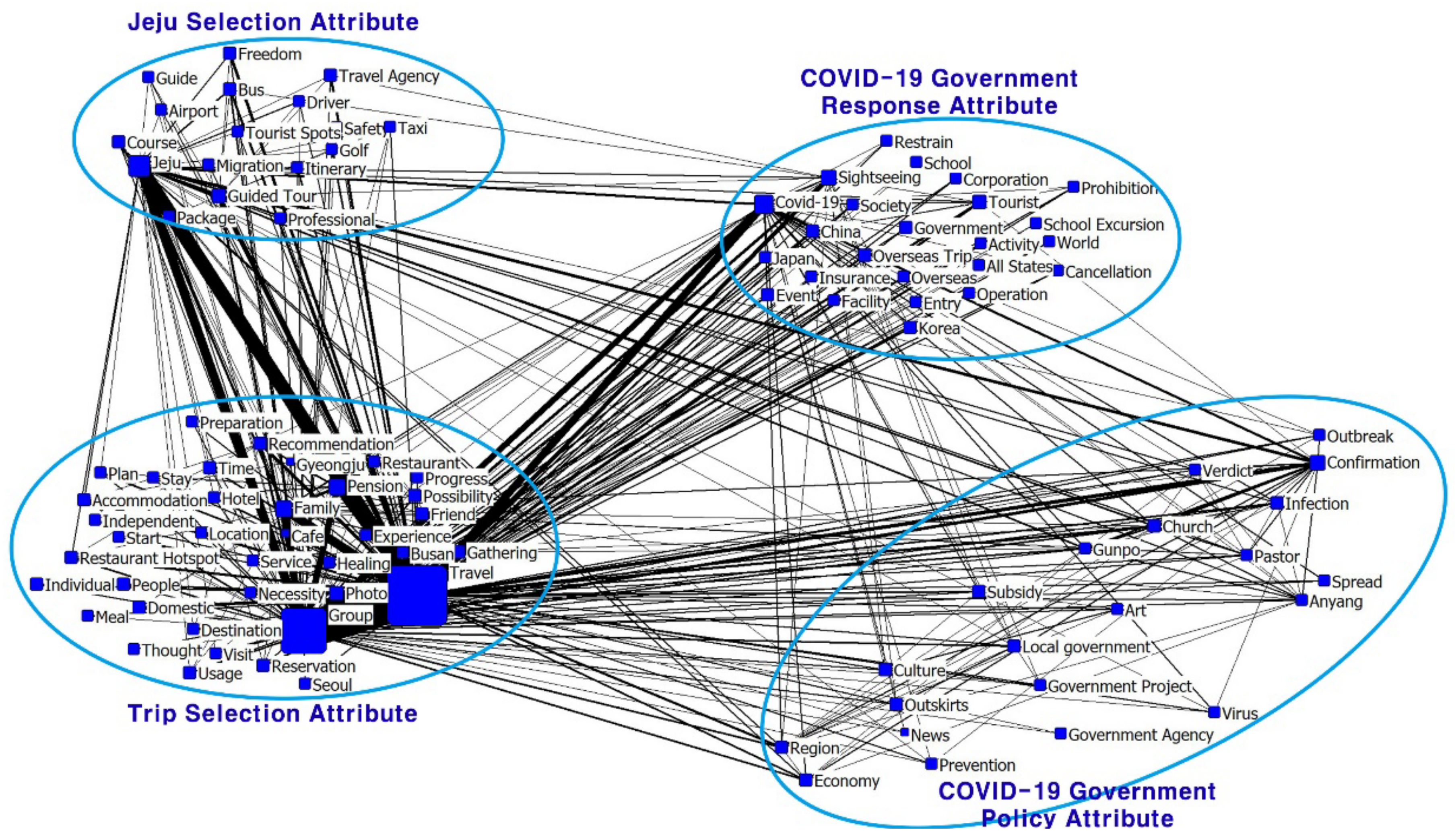

4.2. Semantic Network Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Timeline-COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/08-04-2020-who-timeline---COVID-19 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- UNWTO. International Tourism and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/international-tourism-and-COVID-19 (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Herald Economy. Available online: http://biz.heraldcorp.com/view.php?ud=20200203000117&ACE%20.SEARCH=1 (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- KDCA (Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention). Available online: https://www.cdc.go.kr/cdc_eng/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- KBS NEWS. Available online: http://news.kbs.co.kr/news/view.do?ncd=4508794 (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Farzanegan, M.R.; Gholipour, H.F.; Feizi, M.; Nunkoo, R.; Andargoli, A.E. International Tourism and Outbreak of Coronavirus (COVID-19): A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, V.; Grech, P.; Fabri, S. A risk balancing act—Tourism competition using health leverage in the COVID-19 era. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2020, 31, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madani, A.; Boutebal, S.E.; Benhamida, H.; Bryant, C.R. The Impact of Covid-19 Outbreak on the Tourism Needs of the Algerian Population. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, A.; Santos, C. The Impacts of COVID-19 Crisis over the Tourism Expectations of the Azores Archipelago Residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Culture and Tourism Institute. Available online: https://know.tour.go.kr/ptourknow/knowplus/kChannel/kChannelPeriod/kChannelPeriodDetail19Re.do?seq=102903 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Scott, N.; Baggio, R.; Cooper, C. Network Analysis and Tourism: From Theory to Practice; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H. Analysis of Domestic Travel Behavior of Solo Travelers and Their Implications; Korea Institute for Industrial Economics & Trade: Sejong, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Hagan, L.A.R. Motivation of Pleasure Travel and Tourism. In VNR’s Encyclopedia of Hospitality and Tourism; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 798–810. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton, J. Motivations of pleasure vacations. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, D.E. The Tourist Business, 6th ed.; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fodness, D. Measuring tourist motivation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Park, E.H. Cognitive Evaluation of Package Tourism Products and Customer Satisfaction: Controlling on the Mo-tivation of Tourists. Korean J. Tour. Res. 2017, 32, 225–248. [Google Scholar]

- McGhee, N.G.; Loker-Murphy, L.; Uysal, M. The international pleasure travel market: Motivations from a gendered perspective. J. Tour. Stud. 1996, 7, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.-W. An Analysis on the Differences Korean Tourists’ Motivation according to the Travel Typology. J. Int. Trade Commer. 2010, 6, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E. The Relationship among Tourism Motivation, Information Search and Behavioral Intention. J. Event Sci. 2006, 5, 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, P. Tourism Information Technology; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wethner, H.; Klein, S. Information Technology and Tourism: A Challenging Relationship; Springer: Wien, Austria, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.; Wöber, K.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Representation of the Online Tourism Domain in Search Engines. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H. The Effect of Web Site Tourism Information Quality and Usefulness on User Satisfaction. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2004, 16, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.J. End user behavior analysis based upon mobile tourism service experience focusing on university students. Int. J. Tour. Manag. Sci. 2008, 23, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.G.; Park, H.J.; Lee, S.R. The Effect of Tourism Information Website on Satisfaction, Trust and Loyalty: Focused on Tourism Website by Jeju Province. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2003, 15, 137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, M.J.; Nam, I.S.; Jeong, G.H. Research Articles: An Evaluation of Festival Tourism Information by Importance-Performance Analysis: Focused on Geumsan Insam Festival. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2007, 19, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.G.; Jang, J.S.; Kang, J.E. The Research on Evaluating the Quality for an Website of Providing Tourism Information. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2006, 18, 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E.S. How Mobile Tour Information Affects the Image and Satisfaction on that Spots. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2015, 27, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, D.M.; Blobel, B.; Gonzalez, C. Information Information quality in healthcare social media—An architectural approach. Health Technol. 2016, 6, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Heo, J.; Moon, J. A study of tourism information and tourist behavior. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2018, 30, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.G.; Nah, Y.J.; Lim, C.K. An Exploratory Study on the Relationship Between Tourism Motivations and Online Tourism Information Search Behavior. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2005, 5, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, M.; Pigneur, Y.; Steiner, T. The IT-Enabled Extended Enterprise, Applications in the Tourism Industry. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information and Communications Technologies in Tourism, Innsbruck, Austria, 17–19 January 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.Y.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, M.G. The Development of the Storytelling Marketing Strategy through the Analysis of Travel Blogs. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 29, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, B.O. Effects of Quality of Travel Blogs on Intention to Use Applying Extended Technology Acceptance Model and Information System Success Model. J. Tour. Stud. 2013, 25, 81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nationally Accredited Designated Statistics. Available online: https://www.nia.or.kr/site/nia_kor/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=99835&bcIdx=22505&parentSeq=22505 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Korean Statistical Information Service. Available online: https://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsListIndex.do?menuId=M_01_01&vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parmTabId=M_01_01 (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Cho, S.H. A Study on Leisure Attitude, Leisure Immersion, Leisure Satisfaction of Hornyeojok. J. Cult. Prod. Des. 2017, 51, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.-S. The Effect of Solo Travel on Self-Reflection and Satisfaction of Life. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2019, 31, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea JoongAng Daily. Available online: https://news.joins.com/article/23890223 (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Laesser, C.; Bertelli, P.; Riklin, T. Solo travel: Explorative insights from a mature market (Switzerland). J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H. Market Characteristics and Direction on Foreign Individual Traveler (FIT) Policy; Korea Culture & Tourism Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.R.; Kim, H.Y. An Empirical Study on Preference Tour Activities, Tour Constraints, Destination Selection Attribute of F.I.T. Tourist. Int. J. Tour. Manag. Sci. 2011, 26, 331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.Y.; Baik, H.-J.; Lee, C.-K. The role of perceived behavioural control in the constraint-negotiation process: The case of solo travel. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Song, Y.M. The Satisfaction of the Japanese Tourist: What are Differences in Terms of Specific Satisfaction between Individual and Package Tour. East Asian Stud. 2012, 62, 297–330. [Google Scholar]

- Baik, H.J.; Lee, C.K.; Kim, J.O. Examining Structure Relationships between Travel Constraints, Negotiation, Attitude, and Behavior Intention for Domestic Solo Travelers: The Case of 2040 Ages of Single Household. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2015, 27, 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.E. The Study on Tourism Constraints Perception and Participation Intention by Motivation on ‘Travel Alone’ Focused on the University Students in Daegu-Gyeongbuk Area. Tour. Res. 2016, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.W.; Yanxia, Z.; Zhi, P.C.P. Understanding High Levels of Singlehood in Singapore. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2012, 43, 731–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Abbott, D.A. Waiting for Mr. Right: The Meaning of Being a Single Educated Chinese Female Over 30 in Beijing and Guangzhou. Women Stud. Int. Forum 2013, 40, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, E.; Prideaux, B. Crisis Management: A Suggested Typology. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2005, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, N.; Yang, Z. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1994, 11, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.C. Determinants of revisit intention to Seoul by Chinese tourists: The comparison of group tourist and FIT. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2016, 28, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.C.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, J.S. An Analysis of Tourist Destination Routes of Chinese Group Tourists and FIT Visiting in Seoul Korea. J. Hotel Resort 2017, 16, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.H.; Oh, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Travel Guidance Interface for FIT (Foreign Independent Tourists). J. Digit. Des. 2008, 8, 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, A. Tourism, Technology and Competitive Strategies; CAB: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Hsieh, A.C. Is the tour leader an effective endorser for grouppackage tour brochures? Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanai, T.; Oguchi, T.; Ando, K.K. Yamaguchi Important attributes of lodgings to gain repeat business: A comparison between individual travels and group travels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Travel Anxiety and Intentions to Travel Internationally: Implications of Travel Risk Perception. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Song, H.J. The Effect of the Perception of Influenza A(H1N1) on International Travel Decision-making Process of Group Tourists. J. Tour. Sci. 2011, 35, 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, B.; Smith, W.; Li, X. An Exploratory Study of Travelers’ Use of Online Reviews and Recommendations. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2009, 11, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shih, H.-Y. Network characteristics of drive tourism destinations: An application of network analysis in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.T.T.; Ananda, S.J.; Zahra, P. Social network analysis in tourism services distribution channels. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.C. Social Network Analysis; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl, T.; Agneessens, F.; Skvoretz, J. Node centrality in weighted networks: Generalizing degree and shortest paths. Soc. Netw. 2010, 32, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agata, R.; Gozzo, S.; Tomaselli, V. Network analysis approach to map tourism mobility. Qual. Quant. 2012, 47, 3167–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.; Rob, L.; Bin, G.; Wei, C. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 634–639. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, G.; Barnes, S.J.; Khuong, L.N.; Qiong, J. A Theoretical Approach to Online Review Systems: An Influence of Review Components Model. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Chiayi City, Taiwan, 27 June–1 July 2016; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, C.W. Analysis of Meaning of Social Conflict Discussion in Korea: Focusing on Key Word Network in Major Portals. J. Polit. Commun. 2017, 45, 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann, M.S. Multicultural keywords and network analysis using big data. Soc. Converg. Knowl. Trans. 2018, 6, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Internettrend. A Website That Provides the Share of Internet Search by Portal in Korea. Available online: http://www.internettrend.co.kr/trendForward.tsp (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Park, S.H.; Lee, C.H. The traditional market activation factor derivation research through social big data-focused on Seoul City Mangwon market and Suyu market. Seoul Stud. 2018, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeman, L.C. Ucinet: Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki, N.L.; Wellman, N.S.; Amundson, D.R. Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, E.; Little, D.A. ‘Relative Escape’? The Impact of Constraints on Women Who Travel Solo. Tour. Rev. Int. 2005, 9, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, M. Meanings of female solo travel: A perspective of autoethnography. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Elaine, C.L.Y.; Mona, Y.; Catheryn, K.L. The meanings of solo travel for Asian women. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbert, M.G. Healing Places; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Rada, R. Structured hypertext with domain semantics. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 1998, 16, 372–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Travel | 38,951 | 12.85% | 35 | Experience | 573 | 0.19% | 69 | China | 360 | 0.12% |

| 2 | Solo | 19,200 | 6.33% | 36 | Narrative | 557 | 0.18% | 70 | Day | 354 | 0.12% |

| 3 | Jeju | 3129 | 1.03% | 37 | Taiwan | 543 | 0.18% | 71 | Trip tribe | 353 | 0.12% |

| 4 | Overseas Trip | 2755 | 0.91% | 38 | Broadcast | 526 | 0.17% | 72 | Train | 349 | 0.12% |

| 5 | Female | 2631 | 0.87% | 39 | Bus | 503 | 0.17% | 73 | Flight | 349 | 0.12% |

| 6 | People | 1637 | 0.54% | 40 | Mind | 495 | 0.16% | 74 | Wondering | 349 | 0.12% |

| 7 | Time | 1357 | 0.45% | 41 | Bangkok | 494 | 0.16% | 75 | Battle Trip | 346 | 0.11% |

| 8 | Photo | 1337 | 0.44% | 42 | Sightseeing | 483 | 0.16% | 76 | Backpack | 345 | 0.11% |

| 9 | Friend | 1293 | 0.43% | 43 | Airport | 482 | 0.16% | 77 | Fukuoka | 343 | 0.11% |

| 10 | Recommendation | 1221 | 0.40% | 44 | Travelog | 470 | 0.16% | 78 | Daily life | 343 | 0.11% |

| 11 | Plan | 1208 | 0.40% | 45 | Life | 458 | 0.15% | 79 | Love | 341 | 0.11% |

| 12 | Destination | 1188 | 0.39% | 46 | Healing | 454 | 0.15% | 80 | Paris | 340 | 0.11% |

| 13 | Thought | 1185 | 0.39% | 47 | Memory | 444 | 0.15% | 81 | Country | 337 | 0.11% |

| 14 | Hotel | 1151 | 0.38% | 48 | Gangneung | 441 | 0.15% | 82 | Challenge | 332 | 0.11% |

| 15 | Family | 1090 | 0.36% | 49 | Gyeongju | 434 | 0.14% | 83 | Philippines | 323 | 0.11% |

| 16 | Tourist | 1071 | 0.35% | 50 | Tokyo | 431 | 0.14% | 84 | Shopping | 323 | 0.11% |

| 17 | Freedom | 1014 | 0.33% | 51 | Information | 425 | 0.14% | 85 | Trend | 322 | 0.11% |

| 18 | Europe | 994 | 0.33% | 52 | Thailand | 419 | 0.14% | 86 | Reading | 322 | 0.11% |

| 19 | Accommodation | 970 | 0.32% | 53 | Sea | 418 | 0.14% | 87 | Morning | 320 | 0.11% |

| 20 | Tour | 926 | 0.31% | 54 | Oneself | 417 | 0.14% | 88 | Safety | 320 | 0.11% |

| 21 | Course | 872 | 0.29% | 55 | Reservation | 413 | 0.14% | 89 | Winter | 317 | 0.10% |

| 22 | Japan | 827 | 0.27% | 56 | Village | 411 | 0.14% | 90 | Schedule | 315 | 0.10% |

| 23 | Domestic | 747 | 0.25% | 57 | Introduction | 410 | 0.14% | 91 | Region | 308 | 0.10% |

| 24 | Itinerary | 746 | 0.25% | 58 | Usage | 392 | 0.13% | 92 | Tip | 306 | 0.10% |

| 25 | Café | 744 | 0.25% | 59 | City | 390 | 0.13% | 93 | Airplane | 304 | 0.10% |

| 26 | Companion | 735 | 0.24% | 60 | Guest House | 387 | 0.13% | 94 | USA | 302 | 0.10% |

| 27 | Package | 716 | 0.24% | 61 | Vietnam | 386 | 0.13% | 95 | Osaka | 302 | 0.10% |

| 28 | Busan | 681 | 0.22% | 62 | Hongkong | 381 | 0.13% | 96 | Summer | 299 | 0.10% |

| 29 | Seoul | 659 | 0.22% | 63 | Da Nang | 377 | 0.12% | 97 | Sokcho | 299 | 0.10% |

| 30 | Male | 648 | 0.21% | 64 | Child | 368 | 0.12% | 98 | Nature | 296 | 0.10% |

| 31 | Restaurant Hotspot | 620 | 0.20% | 65 | Fall | 366 | 0.12% | 99 | Street/Avenue | 293 | 0.10% |

| 32 | Preparation | 613 | 0.20% | 66 | Market | 365 | 0.12% | 100 | Culture | 293 | 0.10% |

| 33 | Review | 610 | 0.20% | 67 | Overseas | 365 | 0.12% | ||||

| 34 | Korea | 576 | 0.19% | 68 | Happiness | 362 | 0.12% |

| Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Travel | 25,837 | 9.61% | 35 | Subscription | 554 | 0.21% | 69 | Attraction | 328 | 0.12% |

| 2 | Group | 17,381 | 6.47% | 36 | Workshop | 553 | 0.21% | 70 | Cancellation | 326 | 0.12% |

| 3 | Jeju | 4380 | 1.63% | 37 | Traveler’s insurance | 541 | 0.20% | 71 | Expense | 325 | 0.12% |

| 4 | Family | 2933 | 1.09% | 38 | Guide | 525 | 0.20% | 72 | Accident | 325 | 0.12% |

| 5 | Pension | 2759 | 1.03% | 39 | Europe | 502 | 0.19% | 73 | Travel program | 325 | 0.12% |

| 6 | Tourist | 2156 | 0.80% | 40 | School Excursion | 486 | 0.18% | 74 | Da Nang | 319 | 0.12% |

| 7 | Tour | 1832 | 0.68% | 41 | People | 458 | 0.17% | 75 | Economy | 314 | 0.12% |

| 8 | Sightseeing | 1708 | 0.64% | 42 | Visit | 456 | 0.17% | 76 | Thought | 310 | 0.12% |

| 9 | China | 1424 | 0.53% | 43 | Busan | 453 | 0.17% | 77 | Village | 304 | 0.11% |

| 10 | Accommodation | 1257 | 0.47% | 44 | Visa | 447 | 0.17% | 78 | Comfort | 303 | 0.11% |

| 11 | Japan | 1200 | 0.45% | 45 | Review | 437 | 0.16% | 79 | Travel theme | 301 | 0.11% |

| 12 | Individual | 1196 | 0.45% | 46 | Minibus | 427 | 0.16% | 80 | Safety | 296 | 0.11% |

| 13 | Travel Agency | 1190 | 0.44% | 47 | Taiwan | 414 | 0.15% | 81 | Gyeongju | 294 | 0.11% |

| 14 | Recommendation | 1165 | 0.43% | 48 | Airport | 401 | 0.15% | 82 | Vehicle | 294 | 0.11% |

| 15 | Package | 1149 | 0.43% | 49 | Inclusion | 391 | 0.15% | 83 | Vietnam | 290 | 0.11% |

| 16 | Bus | 1146 | 0.43% | 50 | Backpack | 387 | 0.14% | 84 | Providing | 289 | 0.11% |

| 17 | Travel Packages | 1141 | 0.42% | 51 | Information | 383 | 0.14% | 85 | Café | 283 | 0.11% |

| 18 | Photo | 1116 | 0.42% | 52 | The number of people | 381 | 0.14% | 86 | Fishing | 277 | 0.10% |

| 19 | Freedom | 1095 | 0.41% | 53 | Corporation | 378 | 0.14% | 87 | Promotion | 274 | 0.10% |

| 20 | Reservation | 934 | 0.35% | 54 | Tour Bus | 374 | 0.14% | 88 | Private House | 274 | 0.10% |

| 21 | Overseas Trip | 892 | 0.33% | 55 | Restaurant Hotspot | 372 | 0.14% | 89 | Price | 271 | 0.10% |

| 22 | Domestic | 749 | 0.28% | 56 | Healing | 367 | 0.14% | 90 | Cost | 270 | 0.10% |

| 23 | Destination | 747 | 0.28% | 57 | Seoul | 364 | 0.14% | 91 | Korean | 269 | 0.10% |

| 24 | Itinerary | 737 | 0.27% | 58 | Flight | 360 | 0.13% | 92 | Walking | 268 | 0.10% |

| 25 | Course | 733 | 0.27% | 59 | Application | 358 | 0.13% | 93 | Gangwondo | 266 | 0.10% |

| 26 | Region | 729 | 0.27% | 60 | Summer | 355 | 0.13% | 94 | Speciality | 266 | 0.10% |

| 27 | Time | 709 | 0.26% | 61 | Resort | 350 | 0.13% | 95 | Sea | 263 | 0.10% |

| 28 | Gathering | 664 | 0.25% | 62 | Overseas | 349 | 0.13% | 96 | Fall | 260 | 0.10% |

| 29 | Rent | 663 | 0.25% | 63 | Festival | 345 | 0.13% | 97 | Meal | 258 | 0.10% |

| 30 | Friend | 646 | 0.24% | 64 | School | 343 | 0.13% | 98 | Market | 256 | 0.10% |

| 31 | Preparation | 640 | 0.24% | 65 | Local | 341 | 0.13% | 99 | Introduction | 252 | 0.09% |

| 32 | Experience | 632 | 0.24% | 66 | Cebu city | 338 | 0.13% | 100 | Participation | 250 | 0.09% |

| 33 | Hotel | 599 | 0.22% | 67 | Service | 333 | 0.12% | ||||

| 34 | Plan | 591 | 0.22% | 68 | Child | 332 | 0.12% |

| Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Travel | 111,574 | 10.33% | 35 | Narrative | 1953 | 0.18% | 69 | Day Trip | 1230 | 0.11% |

| 2 | Solo | 44,492 | 4.12% | 36 | Prep | 1937 | 0.18% | 70 | Price | 1213 | 0.11% |

| 3 | Jeju | 19,782 | 1.83% | 37 | Sea | 1918 | 0.18% | 71 | Yeosu | 1206 | 0.11% |

| 4 | People | 6401 | 0.59% | 38 | Seoul | 1916 | 0.18% | 72 | Airplane | 1195 | 0.11% |

| 5 | COVID-19 | 6224 | 0.58% | 39 | Japan | 1900 | 0.18% | 73 | StreetAvenue | 1154 | 0.11% |

| 6 | Female | 5963 | 0.55% | 40 | Korea | 1898 | 0.18% | 74 | Memory | 1145 | 0.11% |

| 7 | Time | 5650 | 0.52% | 41 | Review | 1894 | 0.18% | 75 | Village | 1126 | 0.10% |

| 8 | Thought | 5082 | 0.47% | 42 | Airport | 1851 | 0.17% | 76 | Movie | 1120 | 0.10% |

| 9 | Photo | 5005 | 0.46% | 43 | Healing | 1832 | 0.17% | 77 | Travelog | 1119 | 0.10% |

| 10 | Accommodation | 4871 | 0.45% | 44 | Guest House | 1824 | 0.17% | 78 | China | 1106 | 0.10% |

| 11 | Recommendation | 4577 | 0.42% | 45 | Culture | 1820 | 0.17% | 79 | Restaurant | 1102 | 0.10% |

| 12 | Friend | 4311 | 0.40% | 46 | Location | 1779 | 0.16% | 80 | London | 1092 | 0.10% |

| 13 | Overseas | 4201 | 0.39% | 47 | World | 1732 | 0.16% | 81 | Gangwondo | 1091 | 0.10% |

| 14 | Europe | 4035 | 0.37% | 48 | Companion | 1685 | 0.16% | 82 | Vacation | 1089 | 0.10% |

| 15 | Café | 3869 | 0.36% | 49 | Love | 1571 | 0.15% | 83 | Experience | 1087 | 0.10% |

| 16 | Subsidy | 3612 | 0.33% | 50 | Happiness | 1555 | 0.14% | 84 | Market | 1086 | 0.10% |

| 17 | Restaurant Hotspot | 3461 | 0.32% | 51 | Traveler | 1543 | 0.14% | 85 | Apprehension | 1082 | 0.10% |

| 18 | Hotel | 3382 | 0.31% | 52 | USA | 1529 | 0.14% | 86 | Safety | 1060 | 0.10% |

| 19 | Domestic | 3338 | 0.31% | 53 | Confirmation | 1484 | 0.14% | 87 | Camping | 1059 | 0.10% |

| 20 | Busan | 3110 | 0.29% | 54 | Taiwan | 1456 | 0.13% | 88 | Provision | 1058 | 0.10% |

| 21 | Course | 3100 | 0.29% | 55 | Sokcho | 1455 | 0.13% | 89 | Product | 1054 | 0.10% |

| 22 | Plan | 2964 | 0.27% | 56 | Morning | 1434 | 0.13% | 90 | Dinner | 1050 | 0.10% |

| 23 | Usage | 2960 | 0.27% | 57 | Male | 1394 | 0.13% | 91 | Meal | 1047 | 0.10% |

| 24 | Guided Tour | 2953 | 0.27% | 58 | Information | 1392 | 0.13% | 92 | Mood | 1042 | 0.10% |

| 25 | Freedom | 2747 | 0.25% | 59 | Daily | 1391 | 0.13% | 93 | Discount | 1033 | 0.10% |

| 26 | Sightseeing | 2653 | 0.25% | 60 | Life | 1390 | 0.13% | 94 | Inclusion | 1011 | 0.09% |

| 27 | Family | 2530 | 0.23% | 61 | Summer | 1388 | 0.13% | 95 | Food | 1008 | 0.09% |

| 28 | Reservation | 2299 | 0.21% | 62 | Daily Life | 1378 | 0.13% | 96 | Record | 1006 | 0.09% |

| 29 | Mind | 2231 | 0.21% | 63 | City | 1301 | 0.12% | 97 | World | 995 | 0.09% |

| 30 | Itinerary | 2163 | 0.20% | 64 | New York | 1289 | 0.12% | 98 | Activity | 988 | 0.09% |

| 31 | Expense | 2162 | 0.20% | 65 | Mother | 1280 | 0.12% | 99 | Beach | 987 | 0.09% |

| 32 | Gangneung | 2034 | 0.19% | 66 | Paris | 1246 | 0.12% | 100 | Weather | 987 | 0.09% |

| 33 | Destination | 2030 | 0.19% | 67 | Visit | 1239 | 0.11% | ||||

| 34 | Bus | 2007 | 0.19% | 68 | Gyeongju | 1237 | 0.11% |

| Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % | Rank | Word | Freq | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Travel | 39,011 | 7.39% | 35 | Government | 1142 | 0.22% | 69 | Healing | 712 | 0.13% |

| 2 | Group | 27,623 | 5.23% | 36 | Freedom | 1126 | 0.21% | 70 | Driver | 703 | 0.13% |

| 3 | Jeju | 7980 | 1.51% | 37 | Time | 1119 | 0.21% | 71 | Stay | 702 | 0.13% |

| 4 | COVID-19 | 6809 | 1.29% | 38 | Course | 1096 | 0.21% | 72 | Pastor | 696 | 0.13% |

| 5 | Family | 4788 | 0.91% | 39 | Event | 1081 | 0.20% | 73 | Package | 686 | 0.13% |

| 6 | Pension | 4605 | 0.87% | 40 | Outskirts | 1063 | 0.20% | 74 | Insurance | 679 | 0.13% |

| 7 | Confirmation | 3200 | 0.61% | 41 | Visit | 1024 | 0.19% | 75 | Taxi | 674 | 0.13% |

| 8 | Sightseeing | 3186 | 0.60% | 42 | Hotel | 1021 | 0.19% | 76 | Operation | 669 | 0.13% |

| 9 | Guided Tour | 2322 | 0.44% | 43 | Gunpo | 1018 | 0.19% | 77 | Gyengju | 666 | 0.13% |

| 10 | Tourist | 2231 | 0.42% | 44 | Overseas | 993 | 0.19% | 78 | Migration | 659 | 0.12% |

| 11 | Photo | 2132 | 0.40% | 45 | Plan | 959 | 0.18% | 79 | Thought | 657 | 0.12% |

| 12 | Region | 1844 | 0.35% | 46 | Cancellation | 944 | 0.18% | 80 | Start | 647 | 0.12% |

| 13 | Recommendation | 1833 | 0.35% | 47 | Society | 936 | 0.18% | 81 | Virus | 640 | 0.12% |

| 14 | Church | 1830 | 0.35% | 48 | Busan | 926 | 0.18% | 82 | Progress | 639 | 0.12% |

| 15 | Gathering | 1771 | 0.34% | 49 | Seoul | 918 | 0.17% | 83 | Destination | 632 | 0.12% |

| 16 | Subsidy | 1636 | 0.31% | 50 | Japan | 913 | 0.17% | 84 | Guide | 625 | 0.12% |

| 17 | Domestic | 1631 | 0.31% | 51 | Activity | 905 | 0.17% | 85 | Café | 618 | 0.12% |

| 18 | People | 1521 | 0.29% | 52 | Itinerary | 875 | 0.17% | 86 | Verdict | 618 | 0.12% |

| 19 | Restaurant Hotspot | 1498 | 0.28% | 53 | Facility | 860 | 0.16% | 87 | Meal | 614 | 0.12% |

| 20 | Korea | 1476 | 0.28% | 54 | Art | 835 | 0.16% | 88 | Location | 610 | 0.12% |

| 21 | China | 1468 | 0.28% | 55 | Prohibition | 829 | 0.16% | 89 | Entry | 603 | 0.11% |

| 22 | Local government | 1452 | 0.28% | 56 | Anyang | 809 | 0.15% | 90 | Tourist Spots | 602 | 0.11% |

| 23 | Economy | 1392 | 0.26% | 57 | Spread | 799 | 0.15% | 91 | Driver | 593 | 0.11% |

| 24 | Bus | 1386 | 0.26% | 58 | Government Project | 795 | 0.15% | 92 | Professional | 582 | 0.11% |

| 25 | Possibility | 1346 | 0.25% | 59 | Experience | 787 | 0.15% | 93 | Restaurant | 579 | 0.11% |

| 26 | Infection | 1287 | 0.24% | 60 | Prevention | 773 | 0.15% | 94 | Necessity | 577 | 0.11% |

| 27 | Reservation | 1251 | 0.24% | 61 | Outbreak | 770 | 0.15% | 95 | School Excursion | 576 | 0.11% |

| 28 | Usage | 1232 | 0.23% | 62 | Corporation | 763 | 0.14% | 96 | Independent | 575 | 0.11% |

| 29 | Accommodation | 1189 | 0.23% | 63 | Safety | 745 | 0.14% | 97 | School | 574 | 0.11% |

| 30 | Travel Agency | 1186 | 0.22% | 64 | Preparation | 741 | 0.14% | 98 | Airport | 573 | 0.11% |

| 31 | Individual | 1180 | 0.22% | 65 | Service | 735 | 0.14% | 99 | Government Agency | 572 | 0.11% |

| 32 | Overseas Trip | 1180 | 0.22% | 66 | Restrain | 734 | 0.14% | 100 | All States | 571 | 0.11% |

| 33 | Culture | 1162 | 0.22% | 67 | World | 731 | 0.14% | ||||

| 34 | Friend | 1161 | 0.22% | 68 | Golf | 729 | 0.14% |

| Frequency | Degree | Eigenvector | Frequency | Degree | Eigenvector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | Rank | Coef. | Rank | Coef. | Rank | Freq | Rank | Coef. | Rank | Coef. | Rank | ||

| Travel | 111,574 | 1 | 5.038 | 1 | 0.659 | 1 | Sightseeing | 2653 | 26 | 0.126 | 31 | 0.021 | 48 |

| Solo | 44,492 | 2 | 2.606 | 2 | 0.588 | 2 | Family | 2530 | 27 | 0.120 | 33 | 0.024 | 40 |

| Jeju | 19,782 | 3 | 1.240 | 3 | 0.314 | 3 | Reservation | 2299 | 28 | 0.122 | 32 | 0.024 | 41 |

| People | 6401 | 4 | 0.280 | 9 | 0.071 | 9 | Mind | 2231 | 29 | 0.100 | 44 | 0.023 | 44 |

| COVID-19 | 6224 | 5 | 0.268 | 10 | 0.052 | 17 | Itinerary | 2163 | 30 | 0.137 | 28 | 0.032 | 26 |

| Female | 5963 | 6 | 0.526 | 4 | 0.148 | 4 | Expense | 2162 | 31 | 0.119 | 35 | 0.026 | 37 |

| Time | 5650 | 7 | 0.260 | 12 | 0.063 | 11 | Gangneung | 2034 | 32 | 0.140 | 27 | 0.034 | 24 |

| Thought | 5082 | 8 | 0.247 | 13 | 0.063 | 12 | Destination | 2030 | 33 | 0.140 | 26 | 0.032 | 27 |

| Photo | 5005 | 9 | 0.262 | 11 | 0.068 | 10 | Bus | 2007 | 34 | 0.135 | 29 | 0.032 | 28 |

| Accommodation | 4871 | 10 | 0.340 | 6 | 0.076 | 8 | Narrative | 1953 | 35 | 0.089 | 47 | 0.022 | 45 |

| Recommendation | 4577 | 11 | 0.348 | 5 | 0.078 | 7 | Prep | 1937 | 36 | 0.109 | 40 | 0.027 | 33 |

| Friend | 4311 | 12 | 0.237 | 16 | 0.06 | 13 | Sea | 1918 | 37 | 0.109 | 41 | 0.025 | 39 |

| Overseas | 4201 | 13 | 0.287 | 7 | 0.079 | 5 | Seoul | 1916 | 38 | 0.097 | 45 | 0.021 | 49 |

| Europe | 4035 | 14 | 0.281 | 8 | 0.079 | 6 | Japan | 1900 | 39 | 0.110 | 38 | 0.03 | 29 |

| Café | 3869 | 15 | 0.240 | 15 | 0.057 | 14 | Korea | 1898 | 40 | 0.087 | 49 | 0.018 | 56 |

| Subsidy | 3612 | 16 | 0.135 | 30 | 0.019 | 53 | Review | 1894 | 41 | 0.120 | 34 | 0.028 | 32 |

| Restaurant Hotspot | 3461 | 17 | 0.235 | 17 | 0.055 | 16 | Airport | 1851 | 42 | 0.118 | 36 | 0.027 | 34 |

| Hotel | 3382 | 18 | 0.201 | 19 | 0.043 | 23 | Healing | 1832 | 43 | 0.108 | 42 | 0.026 | 38 |

| Domestic | 3338 | 19 | 0.242 | 14 | 0.057 | 15 | Guest House | 1824 | 44 | 0.141 | 25 | 0.034 | 25 |

| Busan | 3110 | 20 | 0.184 | 22 | 0.045 | 21 | Culture | 1820 | 45 | 0.081 | 55 | 0.013 | 76 |

| Course | 3100 | 21 | 0.219 | 18 | 0.052 | 18 | Location | 1779 | 46 | 0.083 | 54 | 0.014 | 71 |

| Plan | 2964 | 22 | 0.190 | 21 | 0.047 | 19 | World | 1732 | 47 | 0.076 | 58 | 0.019 | 99 |

| Usage | 2960 | 23 | 0.147 | 24 | 0.028 | 31 | Companion | 1685 | 48 | 0.113 | 37 | 0.029 | 30 |

| Guided Tour | 2953 | 24 | 0.195 | 20 | 0.045 | 22 | Love | 1571 | 49 | 0.061 | 75 | 0.014 | 72 |

| Freedom | 2747 | 25 | 0.181 | 23 | 0.046 | 20 | Happiness | 1555 | 50 | 0.073 | 60 | 0.017 | 57 |

| Frequency | Degree | Eigenvector | Frequency | Degree | Eigenvector | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq | Rank | Coef. | Rank | Coef. | Rank | Freq | Rank | Coef. | Rank | Coef. | Rank | ||

| Travel | 39,011 | 1 | 5.364 | 1 | 0.616 | 1 | Infection | 1287 | 26 | 0.282 | 18 | 0.037 | 28 |

| Group | 27,623 | 2 | 4.122 | 2 | 0.571 | 2 | Reservation | 1251 | 27 | 0.218 | 31 | 0.038 | 26 |

| Jeju | 7980 | 3 | 1.744 | 3 | 0.299 | 3 | Usage | 1233 | 28 | 0.225 | 27 | 0.038 | 27 |

| COVID-19 | 6809 | 4 | 1.167 | 4 | 0.170 | 5 | Accommodation | 1232 | 29 | 0.236 | 24 | 0.048 | 19 |

| Family | 4788 | 5 | 0.981 | 5 | 0.185 | 4 | Travel Agency | 1186 | 30 | 0.221 | 30 | 0.040 | 23 |

| Pension | 4605 | 6 | 0.740 | 6 | 0.169 | 6 | Individual | 1179 | 31 | 0.164 | 45 | 0.030 | 36 |

| Confirmation | 3200 | 7 | 0.734 | 7 | 0.101 | 7 | Overseas Trip | 1162 | 32 | 0.155 | 51 | 0.022 | 63 |

| Sightseeing | 3186 | 8 | 0.564 | 8 | 0.091 | 9 | Culture | 1161 | 33 | 0.188 | 36 | 0.027 | 46 |

| Guided Tour | 2322 | 9 | 0.495 | 9 | 0.092 | 8 | Friend | 1142 | 34 | 0.171 | 44 | 0.037 | 29 |

| Tourist | 2231 | 10 | 0.383 | 11 | 0.060 | 12 | Government | 1126 | 35 | 0.182 | 38 | 0.023 | 57 |

| Photo | 2132 | 11 | 0.259 | 21 | 0.060 | 13 | Freedom | 1118 | 36 | 0.229 | 26 | 0.048 | 20 |

| Region | 1844 | 12 | 0.382 | 12 | 0.051 | 17 | Time | 1096 | 37 | 0.156 | 50 | 0.030 | 37 |

| Recommendation | 1833 | 13 | 0.374 | 13 | 0.071 | 10 | Course | 1081 | 38 | 0.196 | 34 | 0.040 | 24 |

| Church | 1830 | 14 | 0.472 | 10 | 0.063 | 11 | Event | 1063 | 39 | 0.182 | 37 | 0.027 | 47 |

| Gathering | 1771 | 15 | 0.359 | 14 | 0.059 | 14 | Outskirts | 1021 | 40 | 0.190 | 35 | 0.026 | 49 |

| Subsidy | 1636 | 16 | 0.249 | 22 | 0.036 | 30 | Visit | 1018 | 41 | 0.173 | 41 | 0.027 | 48 |

| Domestic | 1631 | 17 | 0.316 | 16 | 0.053 | 16 | Hotel | 963 | 42 | 0.171 | 43 | 0.030 | 38 |

| People | 1521 | 18 | 0.172 | 42 | 0.033 | 33 | Gunpo | 957 | 43 | 0.338 | 15 | 0.045 | 21 |

| Restaurant Hotspot | 1498 | 19 | 0.238 | 23 | 0.049 | 18 | Overseas | 944 | 44 | 0.176 | 40 | 0.028 | 42 |

| Korea | 1476 | 20 | 0.200 | 33 | 0.031 | 35 | Plan | 936 | 45 | 0.159 | 47 | 0.030 | 39 |

| China | 1468 | 21 | 0.224 | 29 | 0.035 | 31 | Cancellation | 926 | 46 | 0.145 | 58 | 0.022 | 64 |

| Local government | 1452 | 22 | 0.235 | 25 | 0.032 | 34 | Society | 918 | 47 | 0.144 | 59 | 0.019 | 74 |

| Economy | 1392 | 23 | 0.292 | 17 | 0.039 | 25 | Busan | 913 | 48 | 0.155 | 52 | 0.028 | 43 |

| Bus | 1386 | 24 | 0.268 | 19 | 0.054 | 15 | Seoul | 904 | 49 | 0.154 | 55 | 0.025 | 50 |

| Possibility | 1346 | 25 | 0.225 | 28 | 0.040 | 22 | Japan | 875 | 50 | 0.138 | 61 | 0.024 | 52 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sung, Y.-A.; Kim, K.-W.; Kwon, H.-J. Big Data Analysis of Korean Travelers’ Behavior in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010310

Sung Y-A, Kim K-W, Kwon H-J. Big Data Analysis of Korean Travelers’ Behavior in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010310

Chicago/Turabian StyleSung, Yun-A, Kyung-Won Kim, and Hee-Ju Kwon. 2021. "Big Data Analysis of Korean Travelers’ Behavior in the Post-COVID-19 Era" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010310

APA StyleSung, Y.-A., Kim, K.-W., & Kwon, H.-J. (2021). Big Data Analysis of Korean Travelers’ Behavior in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability, 13(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010310