Aiming at the Organizational Sustainable Development: Employees’ Pro-Social Rule Breaking as Response to High Performance Expectations

Abstract

1. Introduction

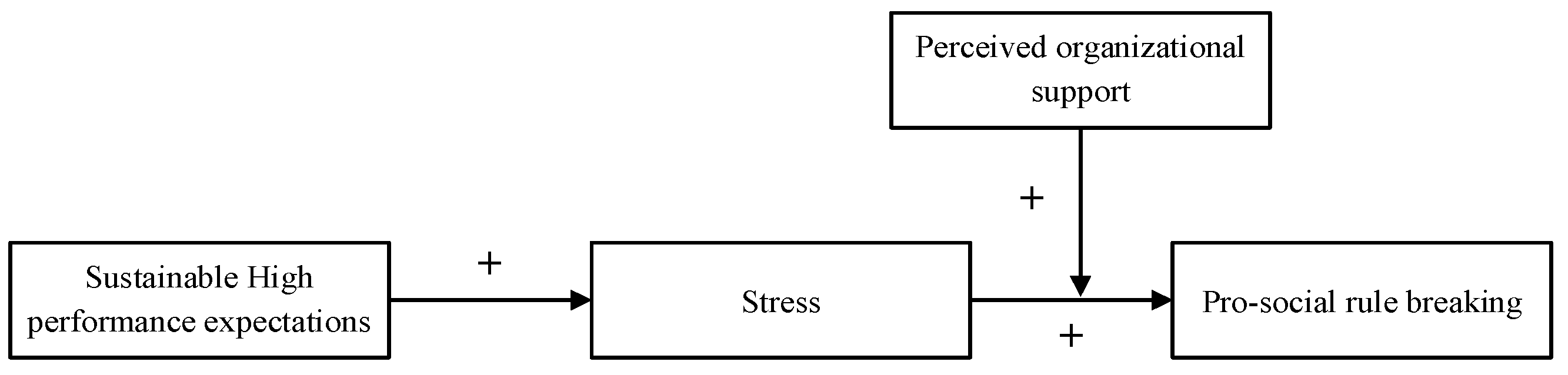

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Pro-Social Rule Breaking and COR Theory

2.2. High Perofrmance Expectations and Stress

2.3. Stress and Pro-Social Rule Breaking

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Perceived Organizational Support

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. High Performance Expectations

3.2.2. Stress

3.2.3. Perceived Organizational Support

3.2.4. Pro-Social Rule Breaking

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Biases Test and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

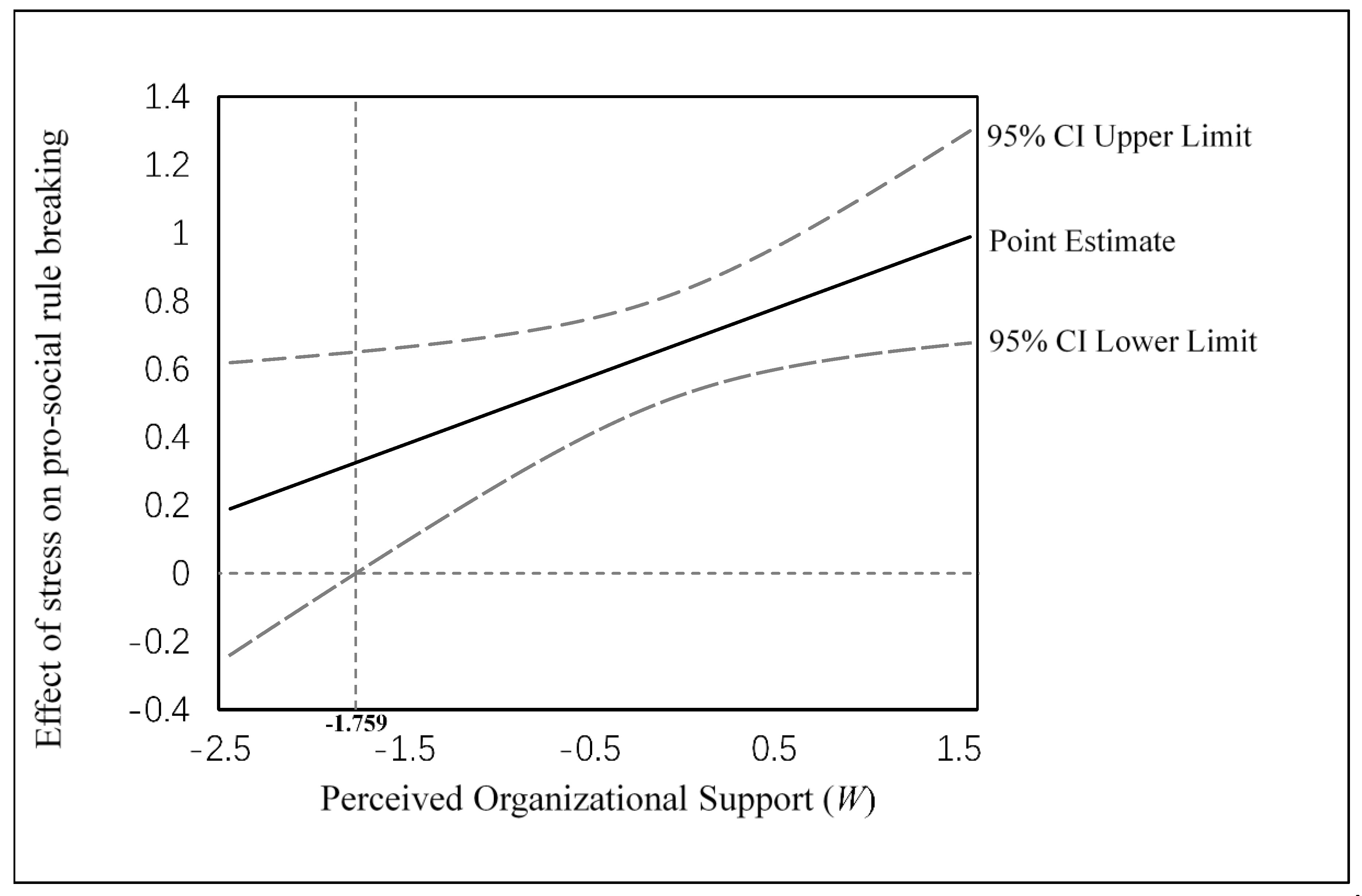

4.3. Tests of Hypotheses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Pro-Social Rule Breaking

Appendix A.2. High Performance Expectations

Appendix A.3. Stress

Appendix A.4. Perceived Organizational Support

References

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963; Volume 2, pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, D.S. Modern organization theory: A psychological and sociological study. Psychol. Bull. 1966, 66, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.H.; Adams, S.W. The Life Cycle of Rules. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. The Dynamics of Organizational Rules. Am. J. Sociol. 1993, 98, 1134–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency Theory: An Assessment and Review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.K.; Marcus, A.A. Rules Versus Discretion: The Productivity Consequences of Flexible Regulation. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Morrison, E.W. Doing the Job Well: An Investigation of Pro-Social Rule Breaking. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R. Bend a Little to Move It Forward: Pro-Social Rule Breaking in Public Health Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dahling, J.J.; Chau, S.L.; Mayer, D.M.; Gregory, J.B. Breaking rules for the right reasons? An investigation of pro-social rule breaking. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaman, J.M.; Gondo, M.B.; Allen, D.G. Ethical climate and pro-social rule breaking in the workplace. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, M.E.B.; Vardaman, J.M.; Hancock, J.I. The role of ethical climate and moral disengagement in well-intended employee rule breaking. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2016, 16, 1159. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.; Zhao, H. Does Organization Citizenship Behavior Really Benefit to Organization: Study on the Compulsory Citizenship Behavior in China. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2011, 14, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefin, S.; Arif, I.; Raquib, M. High-Performance Work Systems and Proactive Behavior: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G.P.; Locke, E.A. Enhancing the Benefits and Overcoming the Pitfalls of Goal Setting. Organ. Dyn. 2006, 35, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, G.P.; Borgogni, L.; Petitta, L. Goal Setting and Performance Management in the Public Sector. Int. Public Manag. J. 2008, 11, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favero, N.; Meier, K.J.; O’Toole, L.J. Goals, Trust, Participation, and Feedback: Linking Internal Management with Performance Outcomes. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, M.E.; Ordóñez, L.; Douma, B. Goal setting as a motivator of unethical behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B.; Sachau, D.A.; Doll, B.; Shumate, R. Sandbagging in Competition: Responding to the Pressure of Being the Favorite. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, N.C.; Sivanathan, N.; Gladstone, E.; Marr, J.C. Rising stars and sinking ships: Consequences of status momentum. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lount, R.B., Jr.; Pettit, N.C.; Doyle, S.P. Motivating underdogs and favorites. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2017, 141, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, D.; Sonnentag, S. Rethinking the effects of stressors: A longitudinal study on personal initiative. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.; Shore, L.; Liden, R. Perceived Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange: A Social Exchange Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sucharski, I.L.; Rhoades, L. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Desmette, D.; Caesens, G.; De Zanet, F. The Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support and Affective Commitment. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, P.D.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support and risk taking. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, M.P.; Randall, D.M. Perceived Organisational Support, Satisfaction with Rewards, and Employee Job Involvement and Organisational Commitment. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 48, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Nurunnabi, M.; Subhan, Q.A.; Shah, S.I.A.; Fallatah, S. The Impact of Transformational Leadership on Job Performance and CSR as Mediator in SMEs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liao, J.; Zhang, Y. The Relationship between Performance Appraisal and Worker Counter-ethical Behaviors: Literature Review and Future Perspective. Manag. Rev. 2011, 23, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brief, A.P.; Motowidlo, S.J. Prosocial Organizational Behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.R. Restaurant industry perspectives on pro-social rule breaking: Intent versus action. Hosp. Rev. 2014, 31, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Zhu, J. Ethical leadership and pro-social rule breaking: A dual process model. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2017, 49, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahari, W.I.; Mildred, K.; Micheal, N. The contribution of work characteristics and risk propensity in explaining pro-social rule breaking among teachers in Wakiso District, Uganda. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2017, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, C.J. Prosocial rule breaking at the street level: The roles of leaders, peers, and bureaucracy. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 1191–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Caldwell, J.; Ford, R.C.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Gresock, A.R. Should I serve my customer or my supervisor? A relational perspective on pro-social rule breaking. In Proceedings of the 67th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 6–8 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, X. The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Employee’s Pro-social Rule Breaking. Can. Soc. Sci. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, N.; Jamshed, S.; Mustamil, N.M. Striving to Restrain Employee Turnover Intention through Ethical Leadership and Pro-Social Rule Breaking. Int. Online J. Educ. Leadersh. 2018, 2, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S.; Ouyang, K.; Herst, D.; Farndale, E. Ethical leadership and employee pro-social rule-breaking behavior in China. Asian Bus. Manag. 2018, 17, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borry, E.L.; Henderson, A.C. Patients, Protocols, and Prosocial Behavior: Rule Breaking in Frontline Health Care. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongdao, Q.; Bibi, S.; Khan, A.; Ardito, L.; Nurunnabi, M. Does What Goes around Really Comes Around? The Mediating Effect of CSR on the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Employee’s Job Performance in Law Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C.B.; Andersen, L.B. High Performance Expectations: Concept and Causes. Int. J. Public Adm. 2017, 42, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Woodman, R.W. Innovative Behavior in the Workplace: The Role of Performance and Image Outcome Expectations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, M.; Zidon, I. Effect of goal acceptance on the relationship of goal difficulty to performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, R.D.; Jones, K.W. Effects of work load, role ambiguity, and Type a personality on anxiety, depression, and heart rate. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X. A study on the relationship between job stress and job performance:based on the perspective of positive coping strategy. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2014, 22, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, Y.; Eivazi, Z. The Relationships Among Employees’ Job Stress, Job Satisfaction, and the Organizational Performance of Hamadan Urban Health Centers. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2010, 38, 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Sonnentag, S.; Pluntke, F. Routinization, work characteristics and their relationships with creative and proactive behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Spychala, A. Job Control and Job Stressors as Predictors of Proactive Work Behavior: Is Role Breadth Self-Efficacy the Link? Hum. Perform. 2012, 25, 412–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghitulescu, B.E. Making Change Happen: The Impact of Work Context on Adaptive and Proactive Behaviors. J. Appl. Bahav. Sci. 2013, 49, 206–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E. Design Your Own Job through Job Crafting. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höge, T.; Hornung, S. Perceived flexibility requirements: Exploring mediating mechanisms in positive and negative effects on worker well-being. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2015, 36, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, S.; Peng, C.; Lorinkova, N.M.; Van Dyne, L.; Chiaburu, D.S. Change-oriented behavior: A meta-analysis of individual and job design predictors. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 88, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Sonnentag, S. Antecedents of day-level proactive behavior: A look at job stressors and positive affect during the workday. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.G.; Locke, E.A.; Barry, D. Goal setting, planning, and organizational performance: An experimental simulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1990, 46, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J.; Eisenberger, R.; Ford, M.T.; Buffardi, L.C.; Stewart, K.A.; Adis, C.S. Perceived Organizational Support: A Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Organizational Support Theory. J. Manag. 2015, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, R.R.; Sutton, C.D.; Feild, H.S. Individual differences in servant leadership: The roles of values and personality. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2006, 27, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L.; Liang, J.; Chou, L.-F.; Cheng, B.-S. Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: Research progress and future research directions. In Leadership and Management in China: Philosophies, Theories, and Practices; Chen, C.-C., Lee, Y.-T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Norman, S.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B. The mediating role of psychological capital in the supportive organizational climate—employee performance relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchait, P.; Lee, C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Abbott, J.L. Impact of error management practices on service recovery performance and helping behaviors in the hospitality industry: The mediating effects of psychological safety and learning behaviors. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Hu, X.; Ding, Y. Learning or Relaxing: How Do Challenge Stressors Stimulate Employee Creativity? Sustainability 2019, 11, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, S.H.; Iaconi, G.D.; Matousek, A. Positive and negative deviant workplace behaviors: Causes, impacts, and solutions. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2007, 7, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L.; Cheng, B.-S. A Cultural Analysis of Paternalistic Leadership in Chinese Organization. Indig. Psychol. Res. Chin. Soc. 2000, 13, 127–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; LePine, J.A.; Buckman, B.R.; Wei, F. It’s not fair… or is it? The role of justice and leadership in explaining work stressor–job performance relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 675–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalos, D.L. The Effects of Item Parceling on Goodness-of-Fit and Parameter Estimate Bias in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, W.M.; Schmitt, N. Parameter Recovery and Model Fit Using Multidimensional Composites: A Comparison of Four Empirical Parceling Algorithms. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 379–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J.J.; Gutworth, M.B. Loyal rebels? A test of the normative conflict model of constructive deviance. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Curran, P.J.; Bauer, D.J. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Matthes, J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiller, S.A.; Fitzsimons, G.J.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; McClelland, G.H. Spotlights, floodlights, and the magic number zero: Simple effects tests in moderated regression. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A. Sustainable development: A vital quest. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res 2017, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Jung, D.; Lee, P. How to Make a Sustainable Manufacturing Process: A High-Commitment HRM System. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, N.; Wu, M.; Zhang, M. The Sustainability of Motivation Driven by High Performance Expectations: A Self-Defeating Effect. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, R.F.; Colquitt, J.A. Transformational Leadership and Job Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Core Job Characteristics. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.E.; Bhagat, R.S. Organizational Stress, Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: Where Do We Go From Here? J. Manag. 1992, 18, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Brief, A.P. Feeling good-doing good: A conceptual analysis of the mood at work-organizational spontaneity relationship. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wan, D. Reciprocity as a Moderator in the Curvilinear Relationship between Job Demands and Job Satisfaction. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2008, 11, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- McClenahan, C.A.; Giles, M.L.; Mallett, J. The importance of context specificity in work stress research: A test of the Demand-Control-Support model in academics. Work Stress 2007, 21, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Factors | χ2 | df | χ2/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | Δχ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Four Factors | 142.510 | 48 | 2.969 | 0.896 | 0.925 | 0.097 | |

| Model 2 | Three factors—Stress and POS combined | 199.112 | 51 | 3.904 | 0.842 | 0.882 | 0.118 | 56.602 |

| Model 3 | Two factors—HPEs, stress, and POS combined | 637.214 | 53 | 12.023 | 0.419 | 0.534 | 0.230 | 438.102 |

| Model 4 | All four factors combined | 1012.468 | 54 | 18.749 | 0.065 | 0.235 | 0.292 | 375.254 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender a | 0.466 | 0.500 | — | ||||||

| 2. Age | 32.409 | 5.490 | 0.068 | — | |||||

| 3. Education b | 3.212 | 0.989 | 0.141 * | −0.092 | — | ||||

| 4. HPEs | 3.614 | 0.822 | 0.103 | 0.185 ** | 0.030 | (0.815) | |||

| 5. Stress | 2.798 | 0.555 | 0.218 ** | 0.027 | 0.340 ** | 0.371 ** | (0.796) | ||

| 6. PSRB | 2.263 | 0.687 | 0.194 ** | −0.142 * | 0.180 ** | 0.056 | 0.548 ** | (0.910) | |

| 7. POS | 3.438 | 0.741 | −0.015 | −0.058 | 0.000 | 0.192 ** | −0.167 * | −0.111 | (0.903) |

| Predictors | Stress | PSRB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Gender | −0.1880 * | −0.154 * | −0.252 ** | −0.125 | −0.126 | −0.114 |

| Age | 0.005 | −0.002 | −0.018 * | −0.021 ** | −0.021 *** | −0.020 ** |

| Education | 0.1800 *** | 0.173 *** | 0.098 * | −0.023 | −0.022 | −0.016 |

| Independent variable | ||||||

| HPEs | 0.237 *** | |||||

| Mediator | ||||||

| Stress | 0.673 *** | 0.666 *** | 0.675 *** | |||

| Moderator | ||||||

| POS | −0.027 | −0.038 | ||||

| Interaction term | ||||||

| Stress × POS | 0.200 * | |||||

| R2 | 0.147 | 0.265 | 0.081 | 0.333 | 0.334 | 0.352 |

| ∆R2 | 0.118 *** | 0.252 *** | 0.001 | 0.018 * | ||

| F | 11.710 | 32.482 *** | 5.999 *** | 76.763 *** | 0.255 | 5.482 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Das, A.K.; Weng, H.; Yang, P. Aiming at the Organizational Sustainable Development: Employees’ Pro-Social Rule Breaking as Response to High Performance Expectations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010267

Wang F, Zhang M, Das AK, Weng H, Yang P. Aiming at the Organizational Sustainable Development: Employees’ Pro-Social Rule Breaking as Response to High Performance Expectations. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010267

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fan, Man Zhang, Anupam Kumar Das, Haolin Weng, and Peilin Yang. 2021. "Aiming at the Organizational Sustainable Development: Employees’ Pro-Social Rule Breaking as Response to High Performance Expectations" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010267

APA StyleWang, F., Zhang, M., Das, A. K., Weng, H., & Yang, P. (2021). Aiming at the Organizational Sustainable Development: Employees’ Pro-Social Rule Breaking as Response to High Performance Expectations. Sustainability, 13(1), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010267