The Language of Sustainable Tourism as a Proxy Indicator of Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. The Identification of Tourism Research Impact

2.2. Literature Review on Research Impact Assessment

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Identifying Proxy Indicators of Research Impact

3.2. Selecting Cases of Sustainable Tourism Research Impact

- Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words);

- Underpinning research of the impact in question (indicative maximum 500 words);

- References to the research (indicative maximum of six references);

- Details of the impact (indicative maximum 750 words);

- Sources to corroborate the impact (indicative maximum of 10 references).

3.3. Identifying Proxy Indicators of Sustainable Tourism

4. Results

4.1. Argumentation Structure

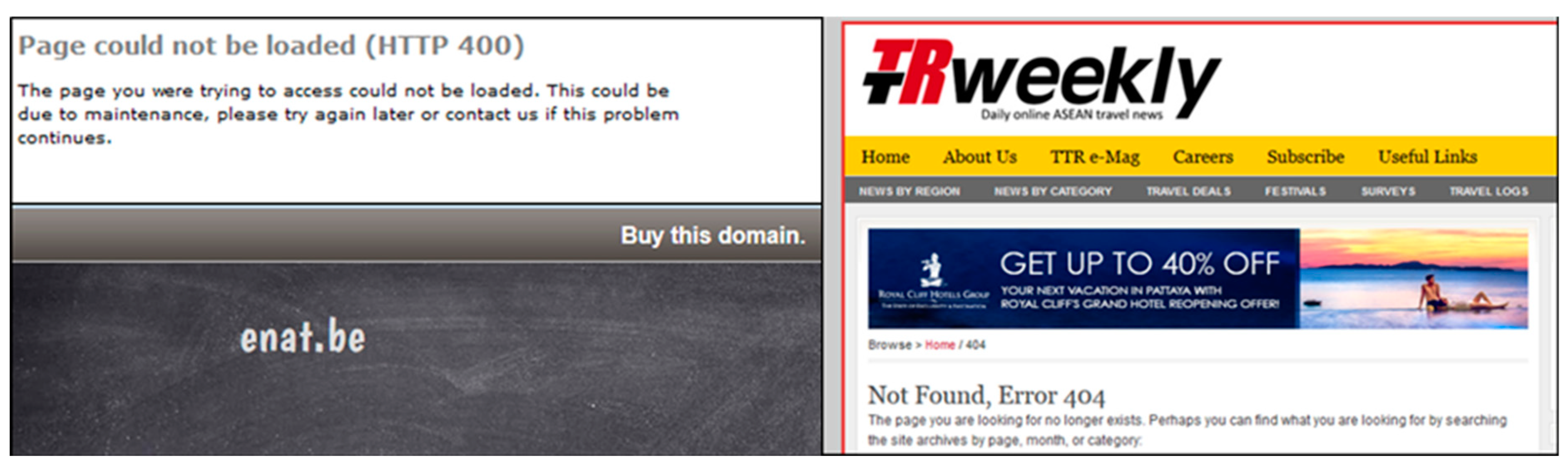

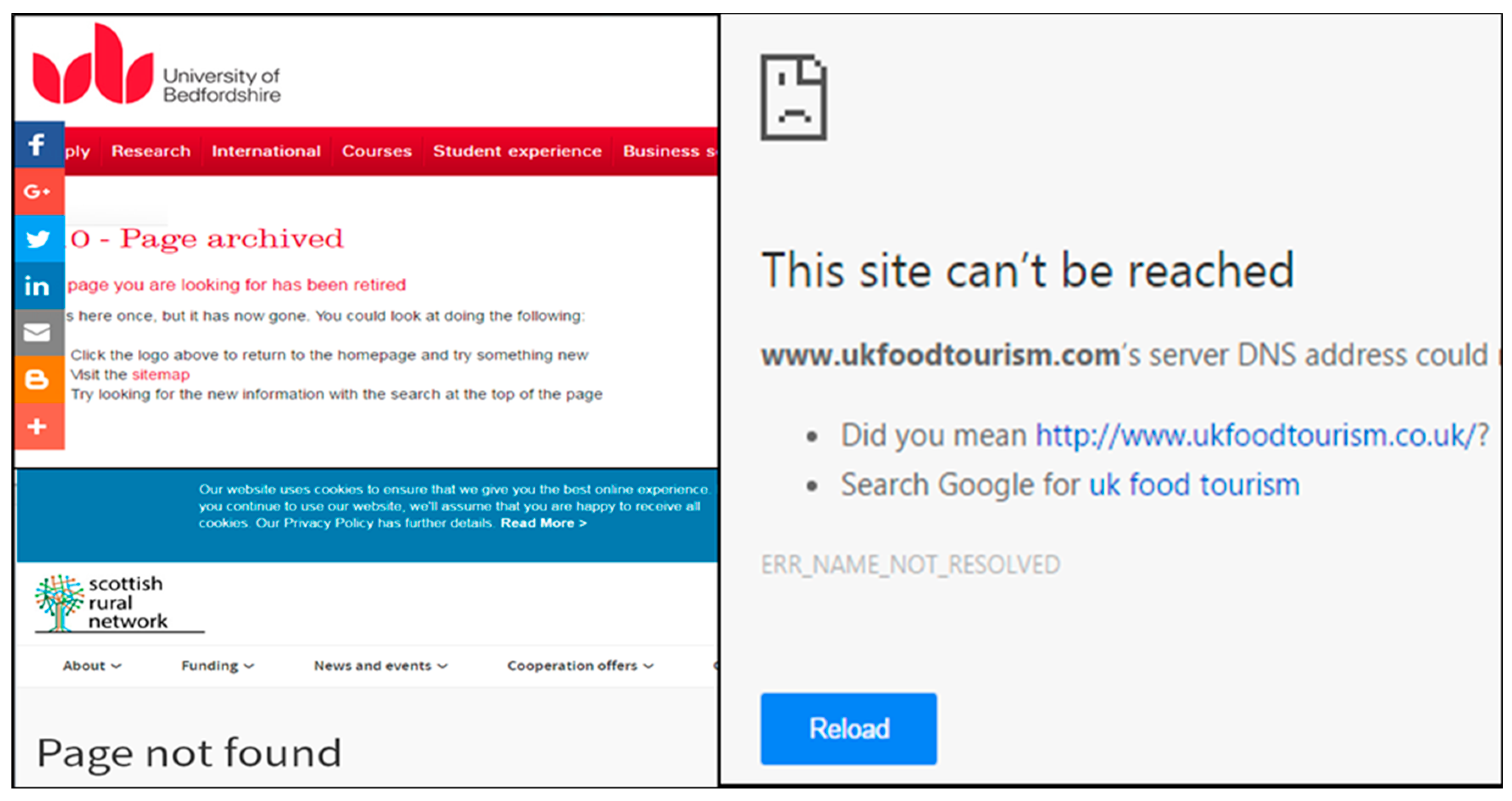

4.2. Challenges in Evidencing

4.3. The Language of Sustainable Tourism Impact

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Butler, R.W. Tourism: An evolutionary perspective. In Tourism and Sustainable Development: A Civic Approach, 2nd ed.; Nelson, J.G., Butler, R., Wall, G., Eds.; University of Waterloo: Waterloo, IA, Canada, 1999; pp. 33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining tourism or something more? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J.; Liburd, J.J. The tourism knowledge system. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gren, M.; Huijbens, E.H. Tourism theory and the earth. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S. Who needs a holiday? Evaluating social tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 667–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoarau, H.; Kline, C. Science and industry: Sharing knowledge for innovation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Grün, B.; Dolnicar, S. Biting off more than they can chew: Food waste at hotel breakfast buffets. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, R.; Dymitrow, M.; Tribe, J. The impact of tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauronen, J.P. The dilemmas and uncertainties in assessing the societal impact of research. Sci. Public Policy 2020, 47, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caton, K. Taking the moral turn in tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1906–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, C.J.; McDonald, S. The researcher role in the attitude-behaviour gap. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 46, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.; Williams, A.M. Tourism and Tourism Spaces; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wadmann, S. Physician–industry collaboration: Conflicts of interest and the imputation of motive. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2014, 44, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, B.R. The Research Excellence Framework and the ‘impact agenda’: Are we creating a Frankenstein monster? Res. Eval. 2011, 20, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Ward, V.; House, A. ‘Impact’ in the proposals for the UK’s Research Excellence Framework: Shifting the boundaries of academic autonomy. Res. Policy 2011, 40, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. The RAE-ification of tourism research in the UK. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2003, 5, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Holt, G.D.; Goulding, J.; Akintoye, A. Interrelationships between theory and research impact: Views from a survey of UK academics. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2014, 21, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, R.; Dymitrow, M.; Tribe, J. A wider research culture in peril: A reply to Thomas. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 86, 103093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REF. Assessment Framework and Guidance on Submissions. Available online: https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/pubs/2011-02/ (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- REF. Panel Criteria and Working Methods. Available online: http://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/pubs/2012-01/ (accessed on 7 October 2012).

- Chubb, J.; Reed, M.S. The politics of research impact: Academic perceptions of the implications for research funding, motivation, and quality. Br. Polit. 2018, 13, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, R. Research Impact, Ethics, And Academic Integrity. The Institute of Applied Ethics, Hull, 10th of March 2020. Recording of the Research Seminar. Available online: https://youtu.be/E5zWj_Mwqdo (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Brauer, R.; Dymitrow, M.; Worsdell, F.; Walsh, J. Maculate reflexivity: Are Universities Losing the plot? In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference Education Culture Society, Wrocław, Poland, 12 September 2020; Available online: https://youtu.be/sGAkEjdwW1I (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Brauer, R. What Research Impact? In Tourism and the Changing UK Research Ecosystem. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Camprubí, R.; Coromina, L. Content analysis in tourism research. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapin, S.; Schaffer, S. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.P. The seamless web: Technology, science, etcetera, etcetera. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1986, 16, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Science in Action: How to Follow Engineers and Scientists Through Society; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, H.; Pinch, T. The Golem. In What Everybody Should Know about Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. We Never Have Been Modern; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie, D.A. Inventing Accuracy: A Historical Sociology of Nuclear Missile Guidance; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bijker, W.E. Of Bicycles, Bakelites and Bulbs. In Toward a Theory of Sociotechnological Change; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, D.N. Putting Science in its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, P.N. A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, H.; Evans, R. Rethinking Expertise; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. On the Pragmatics of Social Interaction: Preliminary Studies in the Theory of Communicative Action; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley, J.E.; Phipps, D. Building the concept of research impact literacy. Evid. Policy J. Res. Debate Pract. 2019, 15, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. On Building a University for the Common Good. Philos. Theory High. Educ. 2020, 2, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R. Why do academics do unfunded research? Resistance, compliance and identity in the UK neo-liberal university. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Fifth Source of Uncertainty: Writing Down Risky Accounts. In Reassembling the Social—An. Introduction to Actor Network Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Watermeyer, R.; Chubb, J. Evaluating ‘impact’ in the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF): Liminality, looseness and new modalities of scholarly distinction. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1554–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, P.; Ovseiko, P.V.; Grant, J.; Graham, K.E.; Boukhris, O.F.; Dowd, A.M.; Sued, O. ISRIA statement: Ten-point guidelines for an effective process of research impact assessment. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. Creating and curating tourism knowledge. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional ecology, translations and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharapos, M.; Marriott, N. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder: Research quality in accounting education. Br. Account. Rev. 2020, 52, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.A.; Page, S.J.; Sebu, J. Achieving research impact in tourism: Modelling and evaluating outcomes from the UKs Research Excellence Framework. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D.; Matthes, J.; Naderer, B. Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. J. Adv. 2018, 47, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, V.L.; Font, X. Volunteer tourism, greenwashing and understanding responsible marketing using market signalling theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 942–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, M.; Van der Duim, R.; Spaargaren, G. The relevance of practice theories for tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 62, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, H.; Santos, J.M. Organisational factors and academic research agendas: An analysis of academics in the social sciences. Stud. High. 2019, 2382–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Holter, C. The repository, the researcher, and the REF: “It’s just compliance, compliance, compliance”. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2020, 46, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D. Performance-based university research funding systems. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Ormerod, N. The (almost) imperceptible impact of tourism research on policy and practice. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griese, K.M.; Werner, K.; Hogg, J. Avoiding greenwashing in event marketing: An exploration of concepts, literature and methods. J. Manag. Sustain. 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, B.; Reed, M.S.; Chubb, J.; Hall, G.; Jowett, L.; Peart, A.; Whittle, A. Writing impact case studies: A comparative study of high-scoring and low-scoring case studies from REF2014. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribe, J. The indiscipline of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 638–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Dymitrow, M.; Grzelak-Kostulska, E.; Biegańska, J. Poverty and social exclusion: An alternative spatial explanation. Bull. Geography. Soc. Econ. Ser. 2017, 35, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civera, A.; Lehmann, E.E.; Paleari, S.; Stockinger, S.A. Higher education policy: Why hope for quality when rewarding quantity? Res. Policy 2020, 49, 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, R.; Watermeyer, R. Competing institutional logics in universities in the United Kingdom: Schism in the church of reason. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsey, K.; Onnis, L.A.; Whiteside, M.; McCalman, J.; Williams, M.; Lui, M.S.; Klieve, H.; Cadet-James, Y.; Baird, L.; Brown, C.; et al. Assessing research impact: Australian Research Council criteria and the case of Family Wellbeing research. Eval. Program. Plan. 2019, 73, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A. Societal Impact as ‘Rituals of Verification’ and The Co-Production of Knowledge. Br. J. Criminol. 2020, 60, 493–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolcott, G.; Keast, R.; Pickernell, D. Deep impact: Re-conceptualising university research impact using human cultural accumulation theory. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1197–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tourism HEI | Name of Case Study |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Analytical Foci | Reading Prompts |

|---|---|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

| Impact Summary: |

Research at the University of Surrey has assisted disabled people and low-income groups to access tourism, a significant non-material aspect of well-being. This was achieved by influencing policy and policy recommendations in the UK, Belgium, and the EU and by influencing behavior, action and policy of either demand or supply:

|

| References: |

| For impact 4.1 |

|

| For impact 4.2 |

|

| For impact 4.3 |

|

| Verb of Inferred Impact | Noun of Inferred Impact | Context of Inferred Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Assist | (Intangible) aspects | Benefits of cross border activity |

| Challenge | Advancements | Charity practices |

| Change | Approaches | Cultural identity and distinctiveness |

| Contribute | Awareness | Evidence based policy/strategy |

| Develop | Capacity | Human resource management |

| Draw upon | Changes | Inclusion of disadvantaged/disabled/low income people |

| Encourage | Decisions | Information Communication Technology |

| Enhance | Demand | Marketing and positioning strategies |

| Enhance | Development | Minimizing undesirable environmental impacts |

| Extend | (Multiplier) effects | Niche tourism |

| Identify | Failures | (Tourism) policy |

| Improve | (Scientific) foundation | Product development |

| Inform | (Economic) growth | Regional and local economies |

| Integrate | Impacts | Small island developing states |

| Introduce | Initiatives | Tourism demand |

| Optimize | Innovations | Tourism Impact Model |

| Plan | (Economic) linkages | Tourism’s socioeconomic impact |

| Predict | Measures | Benefits of cross border activity |

| Provide | Platform | Charity practices |

| Quantify | Practices | Cultural identity and distinctiveness |

| Raise | Recommendations | Evidence based policy/strategy |

| Strengthen | Reduction | |

| Support | Relationship | |

| Underpin | Risks | |

| Understand | Strategy | |

| Use | Supply | |

| Understanding | ||

| (Conventional) wisdom | ||

| Well-being |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brauer, R.; Dymitrow, M. The Language of Sustainable Tourism as a Proxy Indicator of Quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010025

Brauer R, Dymitrow M. The Language of Sustainable Tourism as a Proxy Indicator of Quality. Sustainability. 2021; 13(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrauer, Rene, and Mirek Dymitrow. 2021. "The Language of Sustainable Tourism as a Proxy Indicator of Quality" Sustainability 13, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010025

APA StyleBrauer, R., & Dymitrow, M. (2021). The Language of Sustainable Tourism as a Proxy Indicator of Quality. Sustainability, 13(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010025