Abstract

The process of organizational democracy involves a process of associating employees’ participation and satisfaction in business processes, increased innovation, increased stakeholder engagement and ultimately increased organizational performance. Organizations and the people that form the organization adapt democracy to achieve social and economic goals by making use of the blessings of democracy. In this way, they aim to reach their goals and to include all members of the organization in the process while achieving these goals, and to sustain the stability. The main purpose of this study is to analyze the democracy perceptions of blue and white collar employees in the private sector through organizational democracy scales, by using various variables and to contribute to the existing literature. The sample of the study constitutes 209 people, white and blue collar employees at various levels in medium and large scale enterprises in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone in Turkey. As a result of the study, it is seen that married employees and employees who think that their expertise in the job is good have the power to criticize their businesses and exhibit participation. In addition, it has been concluded that employees that are high school graduates see management fairer in terms of salary than other graduates. Another finding in the study is about the size of the pre-work life centers of the workplace. Perceptions and attitudes of the people living in metropolitan and provincial center metros before work observed that more equality was observed in the workplaces than those living in the district centers.

1. Introduction

Social life has been an important part of life since humanity has existed. In this process, it was observed that there were two parties: those who were managed and those who managed. Along with the concept of democracy, the rule of the people itself has led to a differentiation between the ruling and the ruled. It is possible to talk about the existence of democracy in the past. However, collective activities are only under the supervision of a few people. If it is stated that it is progressing, it is possible to state that democracy does not work properly. This situation caused that it was stated that democracy does not exist. According to Tocqueville, one of the reasons why people prefer to be passionate about equality rather than loving freedom is that they want the permanent and permanent existence of equality in laws, practices, habits, and political organization [1].

Workplace respectability includes a range of values, including freedom, equality, and transparency. However, given the existing organizational structures, it can be said that there is little space for the development of this respectability value, since hierarchies, control mechanisms, governance structures, and bureaucracies are dominant in forming the foundations of contemporary organizations [2]. Therefore, the more hierarchical the management layers of an organization, the more difficult it will be to talk about a full-scale democratization process [3] and the success of the organization of democratization and business processes.

In accordance with Bernstein [4], Carnoy and Shearer [5], Freidan [6], and Stephens [7], workplace democracy is defined as a process of transition of decision-making power from workplace owners and managers to employees [8]. Organizational democracy–just like in political democracy–that employees have a say in management by participating in decisions is a concept used to describe the advanced organizational structures, in which they have the opportunity to improve themselves and display their talents in a structure, supported by an effective communication and information sharing environment and educational activities [9]. Democracy emerges as an organizational form of governance and it is expressed with the concept of organizational democracy. In order to be able to talk about organizational democracy or a democratic organization, employees should be able to participate equally in decisions, be able to criticize and be informed about management’s decisions and practices, be treated fairly, and have organization managers that are accountable [10]. For this reason, real democracy is needed not only to maintain the status of equality among organizational members and external stakeholders, but also to address the ”raison d’être” of the organization itself [11].

The first conceptual dimension of the way organizational democracy is used in enterprises is in the form of industrial democracy. In Turkey, it was executed, applied, and examined through concepts and practices by the practice forms of industrial democracy, which are participatory management, co-management, and self-management [12]. Other manifestations of organizational democracy tendency have been the emergence of programs such as flattening hierarchies and self-managed work teams and employee stock ownership plans. Thus, “empowerment” programs have emerged in various forms. Any action, structure or process that increases the power of a broader and diverse group of people to influence the decisions and activities of an organization can be considered as a movement towards democracy [13].

According to Geçkil and Tikici [3], there are five sub-dimensions of organizational democracy. These are participation-criticism, transparency, justice, equality, and accountability. It is important to pay attention to each of these sub-dimensions separately in order to ensure the perception of organizational democracy and to establish their attitudes and behaviors.

The Manisa Organized Industrial Zone is located in Turkey’s largest industrial zones. There are many businesses around the world here in every sector. For this reason, the study was carried out in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone. This is a field study conducted in collaboration with medium and large-sized enterprises operating in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone (MOSB), in order to determine the attitudes of the managers on issues such as employees’ ability to participate equally in the decisions throughout the enterprise, whether the employees are informed on the decisions made and practices applied by management at all levels, and whether they have the right to criticize these decisions and practices, whether employees are treated fairly, and whether the managers are held accountable or not.

However, there is little research in the literature to measure the perception of organizational democracy of those working on democratic structures. Therefore, little is known about whether organizational democracy positively guides and influences employees’ behavioral orientation. This study is especially to investigate the relationships between demographic variables owned by individual employees and the dimensions of participation-criticism, transparency, fairness, equality and accountability experienced by the employee.

This study makes an important contribution to the field by removing the limitations of the previous research. The first of these contributions are to examine a wide range of global medium and large enterprises with varying degrees of democratic practices, the second is to include many businesses from various sectors in the study, and thirdly, to ensure its reliability by applying the scale developed in the field of organizational democracy in a large organized industrial zone.

In the literature, the issue of organizational democracy has been discussed more often before the 1990s, and there is not a lot of field work on this topic. Although practices of organizational democracy dimensions seem a bit utopian for the Turkish enterprises, the Geçkil and Tikici [1] field study initiated a leadership process in this field with the designation and guidance of the dimensions of organizational democracy. In this context, the results of this study are expected to contribute to the field of organizational democracy and to guide researchers and businesses.

2. Literature Review

Intellectual workers are individuals that feel and carry out change and make the future. They can understand what is required and can take responsibility as long as they are properly taken care of by the management. Furthermore, they have a lot of knowledge and do not need a stick or carrot to innovate. All they need is a sensitive, liberal, and satisfying work environment for them to do their jobs, to provide ideas and insights, to innovate, to test new products and services, and to keep doing their jobs [14]. In order to effectively address and manage new challenges and risks in today’s ever-changing business world, it is important to adopt and maintain a responsive, insightful, and satisfying environment as well as new management and leadership skills.

Democracy means the involvement of members of a business or community in the organization and governance processes. Basically, they can help determine the future of the organizations or communities to which they belong. Nevertheless, workplace democracy manifests differently from political democracy [13]. Democratic governance of enterprises can be regarded as the key to more institutional effectiveness [15] and an obligation to achieve higher levels of innovation and performance [16] promotes long-term value creation and is seen to be compatible with environmental and individual goals [17,18]. Democracy is an organizational structure based on the idea of the redistribution of power within organizations, which, in essence, intends to create a more ethical business [11].

Although seemingly a widely accepted concept, the concept of democracy has been severely criticized (for example, Bachrach [19]). Pateman [20] and Thompson [21], like earlier democratic theorists (for example, Rousseau and JS Mill), point out that democracy depends on participation and that participation in politics is only possible if people were involved in other living spaces. Drawing attention to the importance of the concept of democracy, Cole [22] argues that industry is the key to democracy: participation in politics will be supported particularly by participation in the workplace [8].

Although the idea that democratic principles should play an important role in working life has a long and controversial history, the inclination towards organizational democracy has been increasing in recent years [10]. All organizations should strive to achieve internal democracy in order to achieve their goals as desired, to ensure order and peace within the organization, and to sustain the stability of the organization. Organizational democracy refers to the perfect form of participation of structurally supported employees, including through direct or representative collective consultation, joint decision-making, and self-determination of the concept of democracy. More specifically, organizational democracy brings out temporary or non-transient, continuous, broad-based, and institutionalized employee participation [23]. Organizational democracy, versatile communication between the manager and the ruler, participation in decisions, protection of personal rights, enabling free expression of thoughts, organizational trust, and transparency, etc. There are some mandatory management tools, such as [24]. Although there are different opinions about the definition of organizational democracy, the common point of these definitions is it consists of functions of treating employees fairly, seeing people as an important value, and ensuring their participation in decisions, and organizational democracy is a cultural change that expresses the increase in productivity and value resulting from all of this [25].

To talk about organizational democracy in an organization, the following minimum conditions must exist [26]:

- There should be open and multi-faceted communication between the managed and the manager.

- All parties involved should reflect their will in the organizational decision process.

- The implementation of the decisions should be monitored together, and it is important to check the results of the processes together.

- Personal rights should be protected within the framework of moral and ethical principles as well as laws.

- Everyone should benefit from institutional opportunities under equal conditions.

- Those who will take part in the management bodies must be appointed by election or there must be tools for the supervision of those who are managed.

- An institution suitable for expressing employees’ thoughts freely should be the climate.

- An institution where employees will experience their beliefs and values freely culture should be provided.

- Managers should feel attached to legal rules.

- Employees must have sufficient knowledge of any decision about themselves.

- Corporate trust, openness, and transparency should be provided.

The main objective of organizational democracy is to ensure that organizational members engage with all important aspects of the organization through organizational practices and decision-making processes, and to involve them in business processes [27,28].

Organizational democracy is mainly related to the reversal of top-down management towards bottom-up approaches in organization, change, and decision-making [2]. Instead of traditional management approaches that distribute their tasks to lower-level employees and order them when and how to do their tasks, democracy is accepted as a concept in which the managers working at the enterprise are mainly inclined towards acting as employees’ representatives in the organization, and for this reason, focusing on their own interests and therefore functioning to highlight the interests and dignity of the organization [11].

The need to adapt to constantly changing conditions in businesses, a more professional, and educated workforce, and increasing trends towards “legally competent” employment relationships show that the workplace adopts and defends a democratic understanding. Some researchers also concluded that the adoption of democratic values and practices in organizations has become politically and even morally inevitable [29]. In recent years, many of the nations have turned to a more democratic political and management system. Similarly, corporate executives for many years have been interested in implementing processes that give greater decision-making and management power to a wider consistency group, particularly employees. Success stories based on high achievements, such as Hewlett Packard and Lincoln Electric, helped to stimulate this interest. The involvement and decision-making of employees in these companies led to a high level of innovation and subsequent extraordinary merit and satisfaction in employees [13]. A clear explanation of the relations that support organizations and the structure of organizations show that it is possible to recommend a theory of democracy in the workplace only for the people involved. The idea of equality or the idea that people are not more valuable than others and that people cannot only sacrifice for the benefit of others is more important in the basis of modern society [11].

The most frequently discussed form of organizational democracy is that lower-level employees are associated with decision-making and enhancing the management power of the organization. Organizational democracy can provide many benefits for businesses that continue with actions that empower their employees [13]:

- Employees like to express their wishes or to influence the institutions they work for. Therefore, democracy can promote the commitment to organize and purposeful behavior on behalf of those involved in the decisions.

- Participation in decisions tends to increase employees’ commitment to final decisions.

- The perception of democracy in businesses makes employees feel more responsible for organizational results. This sense of responsibility can reduce the occurrence of behaviors that do not match the values of the particular community in which the organization exists.

- Democratic processes in businesses help create a more specific climate that can increase the ability to innovate and change.

- Giving more discretion to employees and managers, by enabling them to fully develop their skills and abilities, so that they can become more valuable to their organization.

However, despite these expectations, advocates of organizational democracy are often disappointed with the speed and depth of change in organizations. They find that executives are reluctant to share management, to provide autonomy, to disclose information, or to involve employees in important decision-making processes while adopting discourses of democracy, empowerment and participation. It has been observed that employees are not always willing to participate in the decision-making process when making decisions, and this causes more task uncertainty and increased accountability of the results [29].

Organizational democracy is an area where not much work has been done. Weber et al. [23] investigated the effects of perceived participation of employees in democratic decision-making process on pro-social behavior orientations, democratic values, commitment to company, and socio-moral climate perceptions. The study included 325 German-speaking employees from 22 companies in Austria, northern Italy, and southern Germany, which vary according to their levels of organizational democracy (social partnership enterprises, workers’ cooperatives, democratic reform enterprises, and employee-owned companies). The findings show that the participation of employees in democratic organizational decision-making was positively related to the company’s socio-moral climate and their own commitment to organization and socio-behavioral aspects. It also shows that socio-moral climate positively correlates with the commitment of the employees to the organization and that the participation to the decision-making process on the organizational commitment is partly mediated by the socio-moral climate and encourages social and organizational ethical behaviors among the employees.

In his study performed with a total of 174 employees from retail companies in Aydin province of Turkey, Kesen [30] states that all dimensions of organizational democracy positively affect employee performance and that businesses should attach importance to organizational identification and organizational democracy factors in order to increase employee performance.

Geçkil et al. [31] conducted a field study with participation of 405 people working in a university hospital. Their analysis has brought some important results that as the perception of organizational democracy increases, job satisfaction can increase, and that organizational democracy can be used as a tool in increasing the job satisfaction levels of employees. There is a positive relationship between organizational democracy perception and job satisfaction (r = 0.622; p < 0.001). Conrad and Poole [32] mention the factors that cause dissatisfaction in the workplace. Automation can increase productivity for a certain period of time in enterprises but decrease job satisfaction, and this is mentioned among the factors that cause dissatisfaction in the workplace in the literature. The researchers also add that the dissatisfaction would be higher in cases where the work is extremely complex. They also state that job dissatisfaction has a negative relationship with high level of absenteeism and voluntary employee turnover rate as well.

Bakan et al. [33] conducted a field study with employees of four and five star hotels in Marmaris town of Mugla province in Turkey. The analysis of the results shows a significant relationship between all sub-dimensions of organizational democracy and all sub-dimensions of internal entrepreneurship. However, it has been concluded that the perception of transparency, which is one of the organizational democracy sub-dimensions, positively affects innovation and proactivity, and the perception of accountability positively affects innovation and autonomy. However, they found out that other sub-dimensions of organizational democracy, which are participation-criticism, justice and equality perceptions, do not affect the internal entrepreneurial performance of employees.

According to Işık [10], difference and correlation analyses made according to demographic variables could not determine any difference and relationship in terms of gender, marital status, education level, status, and monthly income, but the analyses determined a difference and relationship in terms of age and duration of work.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method

The research is designed to investigate the multivariate relationship of influencing the perceptions of organizational democracy of various variables of private sector employees. Firstly, the study uses Organizational Democracy Scale to determine the organizational democracy perceptions of the private sector employees. The sub-factors of the scale have been determined with Explanatory Factor Analysis (EFA) and later, the reliability of the determined factors is researched with Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Finally, Organizational Democracy (OD) is defined as the dependent variable and the demographic variables of private sector employees are defined as independent variables.

3.2. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with LISREL

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is a statistical technique used to test causal relationships between observed and unobserved (latent) variables and to test interrelated models. SEM is considered to be an important set of statistical methods that provide a hypothesis testing approach to multivariate analysis of structural theory related to a particular study [34]. The implementation steps of SEM, which are commonly used in the evaluation, formulating, and testing of the theoretical models identified in the evaluation of the relationships between variables, are as follows [35]:

- Forming and developing a theoretical model;

- Drawing the path diagram showing causal relationships for the developed theoretical model;

- Obtaining estimates of the model proposed in the study;

- General evaluation of structural model, evaluation of model suitability, and interpretation of results.

3.3. Population and Sampling

The research population consists of white and blue collar employees working in medium and large scale enterprises in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone in 2018–2019 period. The sample of the research is 209 employees that were working in the selected companies during that period and completed the questionnaire. The demographic structure of the sample is detailed in the Section 4.1.

In order to provide the ability to represent the main mass of the employees to be sampled, it is important to choose randomly from medium and large enterprises in MOSB and to select white and blue collar employees among them randomly. However, since entry and exit to the enterprises are very difficult and time consuming, easy sampling method was used in the study. The demographic structure of the sample is given and explained in the Section 4.1.

3.4. Measurement Tool

In organizations, attitude scales are an important and the most frequently used measurement tool to measure employee attitudes. The questionnaires that prepared for an individual to respond to a specific order of propositions in order to discover and reveal that individual’s thoughts and perceptions are defined as attitude scales [36].

It is a five-dimensional Likert-type scale with 28 propositions, formed and developed by Geçkil and Tikici [3]. The Cronbach’s alpha, which is a measure of homogeneity and internal consistency coefficient of the scale, which was developed to measure organizational democracy perceptions of employees, is 0.95. The dimensions of the scale consisted of Participation-Criticism (8), Transparency dimension (6), Justice (5), Equality (6) and Accountability (3) propositions and 21st and 23rd propositions are coded in reverse. The Personal Information form of the scale is a data collection tool developed by the researcher to obtain information about the independent variables. In the questionnaire, there are questions related to gender, age, marital status, education, title, participation in social life and total employment duration in the profession, etc.

4. Findings

According to Yılmaz and Şen [36], factor analysis is the best known and applied statistical technique to investigate the relationships between observed and unobserved (latent) variables. Factor analysis has two different types: Explanatory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). EFA is used when the connections between observed and latent variables are uncertain. On the other hand, CFA is the model that takes into account only the relationships between observed and latent variables in the SEM model and is also called the measurement model of the study. When the researcher has knowledge of the latent variable structure that forms the basis, he or she may prefer DFA instead of EFA. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a technique used to test hypotheses based on factor analysis [37]. DFA is mainly used to test the theory of the researcher’s mind. In this context, the researcher should theoretically know what the scale questions measure. However, doing this with AFA and verifying it with DFA is one of the frequently used ways [38].

4.1. Demographic Structure of the Research

Among the research participants, 34.9% are female, 65.1% are male and 33.5% are between 18–29 years old, 35.5% are between 30–35 years old. 56.9% of participants are between 30–41 years old and 9.6% of them are aged 42 and over. The rate of married workers is 53.6% and the rate of single participants and widowed/divorced are respectively 40.2% and 6.2%. The ratio of employees with primary and secondary education graduates is 24.9%, those with an associate degree is 21.5%, undergraduate degree is 43.1%, and Masters/PhD degree is 10.5%. The ratio of supervisors/chiefs among the participants of the study is 18.7%, whereas those of white collars and blue collars are, 44% and around 37.3%, respectively.

In terms of employment duration in the profession, 50.2% of participants have worked between 1–5 years, 23.9% have worked between 6–11 years, 15.8% have worked between 12–17 years, and around 10% have worked 18 or more years. The 26.3% of the private sector employees earn between 1600–2200 TL, while 49.3% earn between 2201–3400 TL, 12% of them earn between 3401–4000 TL, and 12.4% of them earn more than 4000 TL. The ratio of employees with “high” participation in social life is 12.9%, “medium” is 58.9% and the rate of those who say that they do not participate much in social life is 28.2%.

The ratio of participants that mark their occupational competence (expertise) as “very good” is 18.2%, those who mark it “good” is 48.3%, and those who mark it “medium” is 32.1%, and those who mark it “poor—I am developing it” is 1.4%. The ratio of participants that state that they are residents of the metropolitan area is 92.8% while 5.3% of them say that they live in a district and 1.9% say they live in a village. In total, 35.4% of the private sector employees who answered the question about where they used to live before starting work said they lived in the metropolitan area, 27.8% said they lived in the city center, 20.6% said they lived in a district, and 16.3% said they lived in a village.

4.2. Factor Analysis

4.2.1. Explanatory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Table 1.

Explanatory Factor Analysis Results.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics Analysis.

In the study, before a factor analysis was conducted on the data obtained through the questionnaire, a reliability test was executed and Cronbach’s Alpha value was found to be 0.880. The analysis result of the 28 expressions used in the study was determined to have sufficient reliability.

In the study, the same or very close values obtained as a result of different measurements show that they are reliable and not random. In this context, reliability in field studies is one of the basic conditions of scientific research. In this study, in order to determine the suitability of Organizational Democracy Scale for factor analysis, the Bartlett Test, which determines whether the data and sphericity tests are related to each other, and Kaiser Mayer Olkin (KMO) criterion were used to test the suitability of the sample size in the study for factor analysis [39,40,41]; Bartlett Test Value is calculated as 1863.43 and KMO is calculated as 0.838. In the field studies for social sciences, a KMO value of 0.60 and greater indicates that the sample size taken from the population is sufficient for the research. According to the calculated statistical values, the data are suitable for factor analysis. As a result of explanatory factor analysis, four factors have been obtained, and the 5th factor (Accountability) did not occur.

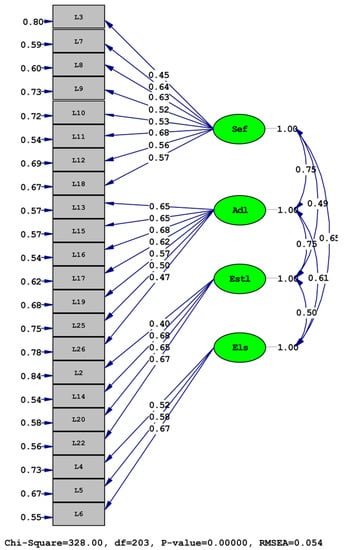

4.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results (CFA)

Four dimensions found through EFA have been verified by using LISREL 8.80 package program with CFA and the data of the Manisa Organized Industry medium and large scale enterprises. The results obtained from the study are presented in Figure 1. The model suitability has been evaluated by taking into account multiple compliance criteria. Criteria Chi-Square = 342.57 (sd = 203), (/sd) = 1.68; RMSEA = 0.054; NFI = 0.90; NNFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.96; GFI = 0.87; RMR = 0.078; SRMR = 0.060.

Figure 1.

Sub-dimensions of Organizational Democracy CFA Results.

They have been considered a good fit and have acceptable compatibility criteria. These results show that the factors obtained from the scale are appropriate. Both EFA and CFA results show that the structure of OMQ is four-dimensional and that the internal consistency and reliability results are sufficient.

4.3. Research Analysis

4.3.1. t-Test Analysis of Participatory Gender for Organizational Democracy

The average of organizational democracy sub-dimensions of the MOSB employees participating in the study is found to be higher for male participants than females (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics.

When the results of the analysis presented in Table 4 are examined, it is seen that the gender of the private sector employees that participated in the research does not have a significant impact on the organizational democracy perception sub-dimensions compared to the significance level of 0.05.

Table 4.

Results of t-Test Analysis of Impact of Gender on Organizational Democracy.

4.3.2. Findings on Impact of Participant Ages on Organizational Democracy

According to information presented in Table 5, the analysis shows that there is no statistically significant impact of age independent variable on organizational democracy perception sub-dimensions compared to the significance level of 0.05.

Table 5.

Variance Analysis Test Results for the Impact of Age on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

4.3.3. Findings on the Impact of Participants’ Marital Status on Organizational Democracy

When the results presented in Table 6 are examined, the marital status independent variable constitutes a statistically significant difference on the “criticism-participation” sub-dimension (p = 0.038 < 0.05) compared to the level of significance of 0.05.

Table 6.

Variance Analysis Test Results on the Impact of Marital Status on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

Due to the difference among the groups, a homogeneity test of variances was performed before proceeding to the Tukey test. Since the effectiveness factor is p = 0.058f 0.05, the variance is homogeneously distributed. Pair comparisons (Tukey test) are made for the factors that are found to be significant according to the analysis results in Table 6.

The Tukey Test (Table 7) shows that the marital status variable makes a difference on the dimension of “criticism-participation” (p = 0.020 < 0.05). Results indicate that the married employees in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone use their right to participate in business processes and criticize more compared to the single employees.

Table 7.

Test Results for Pair Comparison of the Impact of Marital Status on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions (Post Hoc Tests-Tukey).

4.3.4. Findings on Impacts of Participant Education on Organizational Democracy Dimensions

When the results are examined, the education independent variable has a significant difference on the “justice” (p = 0.042 < 0.05) sub-dimension compared to the significance level of 0.05 and the homogeneity test result shows that the variance is homogeneous since the effectiveness factor is p = 0.827 > 0.05. Pair comparisons (Tukey test) are made for the factors that are found to be significant according to the analysis results in Table 8.

Table 8.

Variance Analysis Test Results on Impact of Participant Education on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

According to the analysis results in Table 9, the Tukey test shows that education makes a significant difference on the “justice” dimension. It is possible to say that compared to the employees with Masters/PhD degrees, those with secondary school degrees in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone have perceptions that the management exhibits more fair behaviors.

Table 9.

Pair Comparison Test Results of the Impact of Education on Organizational Democracy (Post Hoc Tests-Tukey).

4.3.5. Findings on the Impact of Participant Titles on Organizational Democracy

According to the results, the title independent variable constitutes a statistically significant difference on the “transparency” (p = 0.043 < 0.05) sub-dimension compared to 0.05 level of significance. A homogeneity test result shows that effectiveness factor is p = 0.077 > 0.05 and variance is homogeneously distributed. Pair comparisons (Tukey test) are made for the factors that are found to be significant according to the analysis results in Table 10.

Table 10.

Variance Analysis Test Results for the Impact of Titles on Organizational Democracy.

The Tukey test shows that the title variable does not cause a difference on the “transparency” dimension of the organizational democracy perception. In terms of effectiveness of title, the Tukey test could not statistically determine which title is more effective on work processes for the employees in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone.

4.3.6. Findings on the Impact of Employment Duration on Employees’ Perceptions of Organizational Democracy

When the results are examined, the employment duration independent variable creates a statistically significant difference on the “equality” (p = 0.044 <0.05) sub-dimension compared to the significance level of 0.05. The homogeneity test results show that the effectiveness factor is p = 0.103 > 0.05 and the variance is homogeneously distributed. Pair comparisons (Tukey test) are made for the factors that are found to be significant according to the analysis results in Table 11.

Table 11.

Variance Analysis Test Results of the Impacts of Employment Duration on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

The Tukey test reveals that the employment duration independent variable does not create a difference on the “equality” sub-dimension of the organizational democracy perception. In terms of employment duration, the test could not statistically determine which employment duration is more effective on work processes for the employees in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone.

4.3.7. Findings on the Impact of Employees’ Income on Organizational Democracy

The income independent variable makes a statistically significant difference on the “justice” (p = 0.020 < 0.05) sub-dimension compared to the significance level of 0.05. The homogeneity test results show that the variance is homogeneous since the effectiveness factor is p = 0.561 > 0.05. Pair comparisons (Tukey test) are made for the factors that are found to be significant according to the analysis results in Table 12.

Table 12.

Variance Analysis Test Results of the Impact of Income on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

In the Tukey test (Table 13), it is seen that the income independent variable makes a difference on the “justice” sub-dimension of democracy perception. We can say that employees who receive low and high salaries in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone are more sensitive to the concept of justice than those who receive medium level salaries.

Table 13.

Test Results of Pair Comparison on the Impacts of Income on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions (Post Hoc Tests-Tukey).

4.3.8. Findings on the Impact of Employee Participation in Social Life on Organizational Democracy

According to the analysis of the results in Table 14, the independent variable of participation in social life does not have a statistically significant impact on organizational democracy perceptions compared to the significance level of 0.05.

Table 14.

Variance Analysis Test Results of the Impact of Employee Participation in Social Life on Organizational Democracy Perception.

4.3.9. Findings on the Impacts of Employees’ Occupational Competence Levels on Democracy Perceptions

The occupational competence level independent variable makes a statistically significant difference on the “criticism-participation” (p = 0.032 < 0.05) sub-dimension compared to the significance level of 0.05, and the homogeneity test results show that the effectiveness factor is p = 0.137 > 0.05 and the variance is homogeneous (Table 15).

Table 15.

Variance Analysis of the Impact of Employees’ Occupational Competence Levels on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

Paired comparisons (Tukey test) are made for the factors that are found to be significant according to the results of the analysis in Table 9, and it is observed that the occupational level independent variable does not cause a difference on the “criticism-participation” sub-dimension of the perception of organizational democracy. When it comes to the impact of the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone employees’ occupational competence levels on work processes, the study could not statistically conclude which level has more impact.

4.3.10. Findings on the Impacts of Employee Location Pre-Work on Perceptions of Democracy

According to the results, there is a statistically significant difference of the employee location pre-work independent variable on the “transparency” (p = 0.020 < 0.05) sub-dimension compared to 0.05 level of significance. A homogeneity test result shows that the variance is homogenous since effectiveness factor for equality factor is (p = 0.656 > 0.05). Pair comparisons (Tukey test) are made for the factors that are found to be significant according to the analysis results in Table 16.

Table 16.

Variance Analysis Test Results on the Impacts Employee Location Pre-Work on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

In the Tukey test, it is seen that the location pre-work independent variable makes a difference on the “equality” sub-dimension of democracy perception. It is observed that among employees working in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone, those who live in the metropolitan area and city centers are more sensitive to the concept of equality than those living in towns (Table 17).

Table 17.

Pair Comparison Test Results (Post-Hoc Tests-Tukey) of the Impact of Employee Location Pre-Work on Organizational Democracy Sub-dimensions.

5. Conclusions

This study makes important contributions to the literature of organizational democracy by overcoming the theoretical study barriers of past research. First of all, this study examines many enterprises from various sectors such as energy, white goods and the automotive supply industry, and this will reveal the private sector’s view of organizational democracy practices. In this context, this study supports the accuracy of the five sub-dimensions obtained by Geçkil and Tikici [3] from their field studies on organizational democracy, since it obtains four of the same sub-dimensions, with the lack of only one sub-dimension—“accountability”.

In this study on the private sector, the reason for lack of accountability dimension could be attributed to “criticism-participation” having the lowest average compared to other dimensions. Establishing a culture of criticism and participation in the decision-making processes of enterprises, in a sense, will also contribute to the culture of accountability to the employees. The study, which has been conducted with both white and blue collar workers in the private sector, shows that there is a culture of transparency, fairness, equality, and criticism-participation of the employees, whereas the culture of accountability is not there yet. The previous studies dealt with the concept of organizational democracy more from a theoretical background perspective, and the use of a new scale is recent, and for this reason, this study makes a contribution to this field.

The important findings obtained from the hypotheses of the study indicate that married employees in the enterprises can more easily criticize the decisions of management compared to single ones, and thus, contribute to the enterprise on an administrative basis. Similarly, the study shows that employees who consider themselves proficient in their professions can criticize and participate in the practice of business functions of management. Compared to employees with Masters/PhD degrees, more of those with secondary degrees state that the management behaved more fairly in the way that business functions were practiced in the workplace. This coincides with situations such as employees’ education, knowledge, skills, expectations from workplace, etc. Similar to this result, compared to the employees who are on a medium level salary scale, the employees who are on lower or higher salary scale say that enterprises are more fair in terms of salary scales. The most important and best findings of the study are on the size of employee location pre-work. The study finds out that those who used to live in the metropolitan area and city centers pre-work have higher perceptions and attitudes about equality in the workplace than those who used to live in towns pre-work.

According to Kerr [29], the idea is that if the labor force is better educated and motivated to participate in the decision-making processes, then they will be willing to take responsibility for the results of these decisions. This study also proves that. It shows that compared to the employees with undergraduate and graduate degrees, those with secondary education perceive and believe enterprise managements to be more fair. On the other hand, the perceptions of white collar employees, who are in a decision-making position with a higher level of education, knowledge, and skills, that enterprise managements cannot behave fairly about business functions, support findings of Kerr [29].

However, the fact that this study is conducted only in the Manisa Organized Industrial Zone, in a single region where western culture is generally considered to be dominant, may be lacking in terms of the implementation and understanding of the dimensions of organizational democracy. It can be concluded that the application and comparison of this topic in different regions and cultures is very important in terms of understanding and predicting the issue of organizational democracy in our country.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B.-M. and H.B.; methodology, D.Z. and F.O.V.; validation, N.B.-M. and H.G.; formal analysis, H.B., F.O.V. and H.G.; investigation, D.Z. and S.D.; resources, N.B.-M. and F.O.V.; writing—original draft preparation, H.B. and H.G., writing—review and editing, N.B.-M. and D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC was funded by the project “Excellence, performance and competitiveness in the Research, Development and Innovation activities at “Dunarea de Jos” University of Galati”, acronym “EXPERT”, financed by the Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation in the framework of Programme 1—Development of the national research and development system, Sub-programme 1.2—Institutional Performance Projects for financing excellence in Research, Development and Innovation, Contract no. 14PFE/17.10.2018.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- De Tocqueville, A. Amerika’da Demokrasi; İletişim Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G. First, Let’s Fire All the Managers. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Geçkil, T.; Tikici, M. Örgütsel Demokrasi Ölçeği Geliştirme Çalışması. Amme İdaresi Derg. 2015, 48, 42–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, P. Workplace Democratization: Its Internal Dynamics; Kent State University Press: Kent, OH, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Carnoy, M.; Shearer, D. Economic Democracy: The Challenge of the 1980s; MW Sharpe: White Plains, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Freidan, K. Workplace Democracy and Productivity; National Center for Economic Alternatives: Washington, DC, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, E.H. The Politics of Workers’ Participation; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zipp, J.F.; Luebke, P.; ve Landerman, R. The social bases of support for workplace democracy. Soc. Perspect. 1984, 27, 395–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral Ataç, L.; Köse, S. Örgütsel Demokrasi ve Örgütsel Muhalefet İlişkisi: Beyaz Yakalılar. İstanb. Üniv. İşletme Fak. Derg. 2017, 46, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Işık, M. Kamu Kurumlarında Örgütsel Demokrasi Algısı (İş-Kur Isparta İl Müdürülüğü Örneği). J. Fac. Ecol. Admin. Sci. 2017, 22, 1661–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, M. Dignity in the Workplace: New Theoretical Perspectives; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Coşan, P.E.; ve Gülova, A.A. Örgütsel demokrasi. Yönetim ve Ekon. 2014, 21, 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.S.; Freeman, R.E. Is organizational democracy worth the effort? Acad. Manag. Exec. (1993–2005) 2004, 18, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, E.; Vanharanta, H. Space for company democracy. In Advances in Human Factors, Business Management, Training and Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Jarley, P.; Fiorito, J.; Delaney, J.T. A Structural Contingency Approach to Bureaucracy and Democracy in U.S. national unions’. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 831–861. [Google Scholar]

- Manville, B.; Ober, J. Beyond Empowerment: Building a Company of Citizens. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cloke, K.; Goldsmith, J. The End of Management and the Rise of Organizational Democracy; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Forcadell, F.J. Democracy, Cooperation and Business Success: The Case of Mondragón Corporación Cooperativa. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 56, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, P. The Theory of Democratic Elitism: A Critique; Bell, D., Ed.; Little, Brown Book Group: Boston, MA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Pateman, C. The Civic Culture: A Philosophic Critique; The Civic Culture Revisted; Almond, G., Verba, S., Eds.; Little, Brown Book Group: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 57–102. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D.F. The Democratic Citizen; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, G.H.D. Self-Government in Industry; G. Bell and Sons: London, UK, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, W.G.; Unterrainer, C.; Schmid, B.E. The influence of organizational democracy on employees’ socio-moral climate and prosocial behavioral orientations. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1127–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, F. In defence of organizational democracy. In Critical Perspectives on Educational Leadership; Smyth, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- Lansbury, D.R. Workplace Democrarcy and the Global Financial Crisis. J. Ind. Relat. 2009, 59, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sadykova, G.; Tutar, H. Örgütsel Demokrasi ve Örgütsel Muhalefet Arasındaki İlişki Üzerine Bir İnceleme. İşletme Bilimi Derg. 2014, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, P.M.; De Jong, S.B. From human resource management to human dignity development: A dignity perspective on HRM and the role of workplace democracy. In Dignity and Organizations; Kostera, M., Pirson, M., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2016; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J.R.; Polanyi, M. Workplace Democracy: Why Bother? Econ. Ind. Democr. 2006, 27, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.L. The limits of organizational democracy. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesen, M. Örgütsel demokrasinin çalışan performansı üzerine etkileri: Örgütsel özdeşleşmenin aracılık rolü. Çankırı Karatekin Üniv. Sos. Bilimler Enst. Derg. 2015, 6, 535–562. [Google Scholar]

- Geçkil, T.; Akpınar, A.T.; Taş, Y. Örgütsel Demokrasinin İş Tatmini Üzerindeki Etkisi: Bir Alan Araştırması. İşletme Araştırmaları Derg. 2017, 9, 649–674. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, C.; Poole, M.S. Strategic Organizational Communication in a Global Economy, 6th ed.; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, İ.; Kara, E.; Güler, B. Örgütsel Demokrasi Algısının Çalışanların İç Girişimcilik Performansına Etkileri: Marmaris’teki Otel İşletmelerinde Bir Alan Araştırması. Hak İş Uluslararası Emek ve Toplum Derg. 2017, 6, 115–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Çelik, H.E.; Yılmaz, V. LISREL 9.1 Ile Yapısal Eşitlik Modellemesi, Temel Kavramlar-Uygulamalar-Programlama, 2nd ed.; Anı Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, V.; Şen, H. Examination of the Effect of Job Satisfaction on Burnout of University Teaching Staff with Structural Equation Model. Arts Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Çokluk, Ö.; Şekercioğlu, G.; Büyüköztürk, Ş. Sosyal Bilimler İçin Çok Değişkenli İstatistik SPSS ve LISREL Uygulamaları; Pegem Akademi: Ankara, Turkey, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Çapık, C. Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışmalarında Doğrulayıcı Faktör Analizinin Kullanılması. Anadolu Hemşirelik ve Sağlık Bilimleri Derg. 2014, 17, 196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Güriş, S.; Ve Astar, M. Bilimsel Araştırmalarda SPSS ile İstatistik, Der Yayınları, İstanbul. 2014. Available online: http://acikerisim.demiroglu.bilim.edu.tr:8080/xmlui/handle/11446/471#sthash.av35LRDR.dpbs (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Büyüköztürk, Ş. Sosyal Bilimler İçin Veri Analizi El Kitabı, 23th ed.; Pegem Akademi: Ankara, Turkey, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, V.; Aktaş, C.; Arslan, M.S.T. Müşterilerin Kredi Kartına Olan Tutumlarının Çoklu Regresyon ve Faktör Analizi İle İncelenmesi. Balıkesir Üniv. Sos. Bilimler Enst. Derg. 2009, 12/22, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).