The Importance of Different Knowledge Types in Health-Related Decisions—The Example of Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

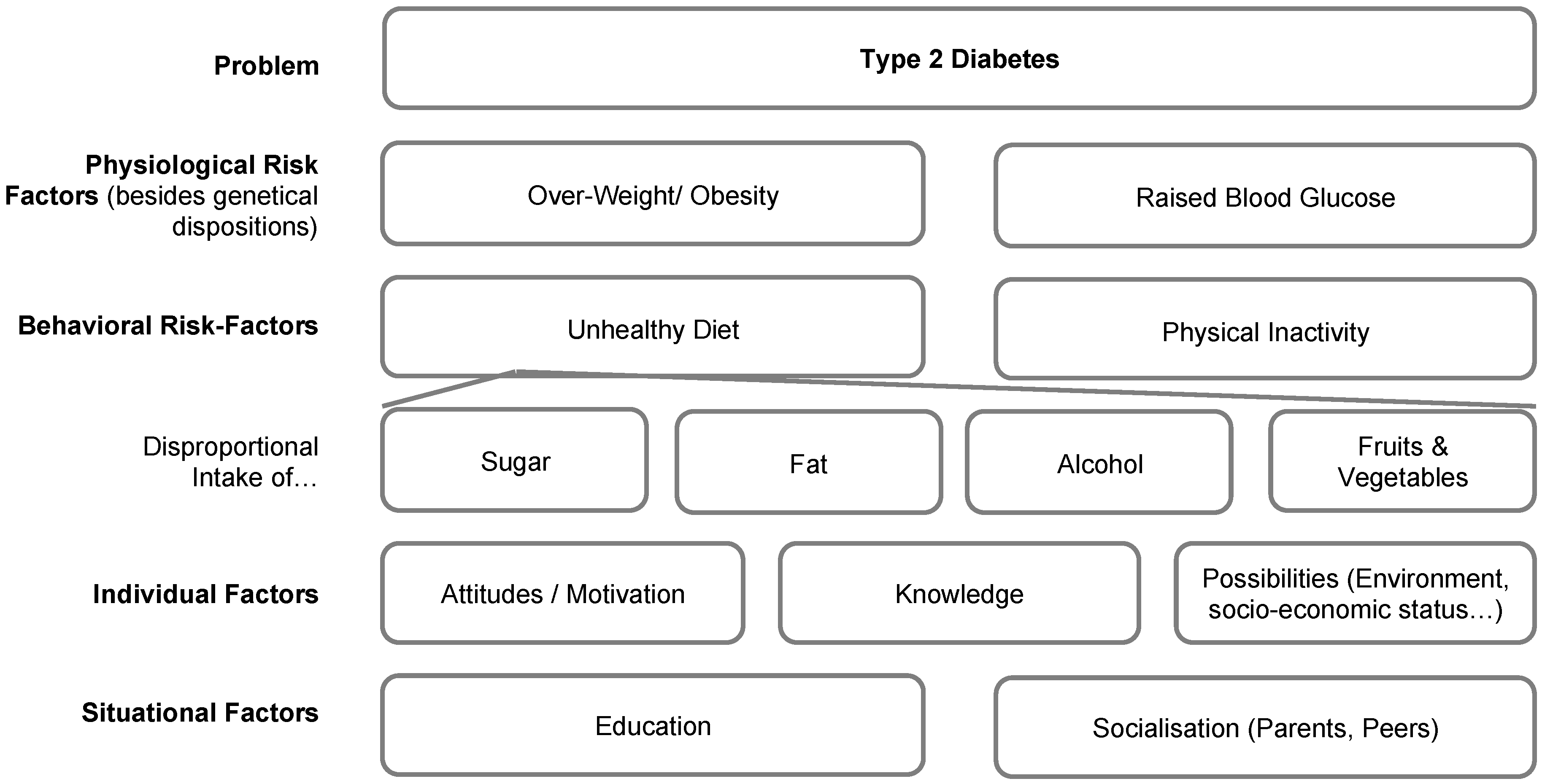

1.1. Problem

1.2. Theoretical Background

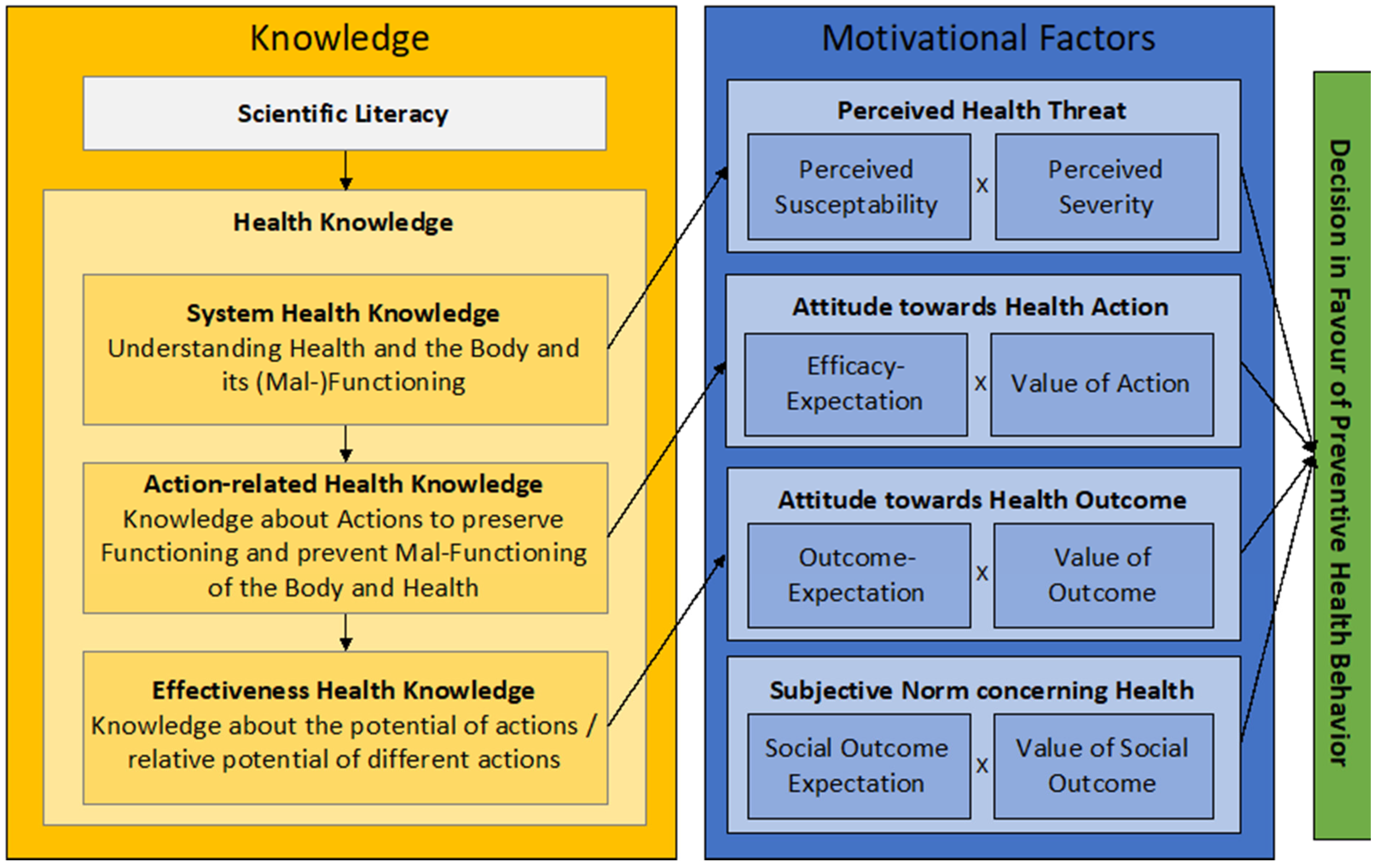

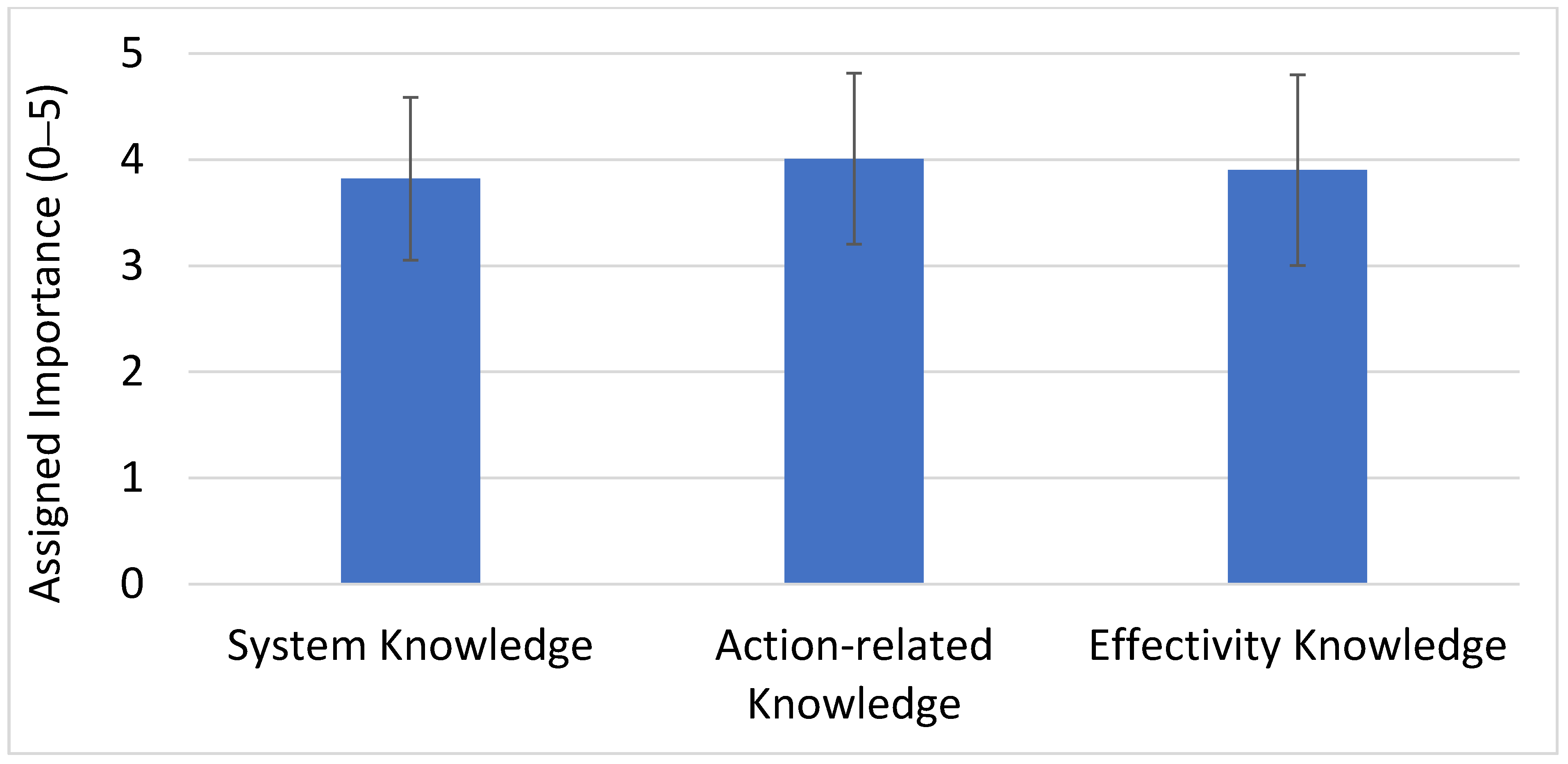

- System Health Knowledge (SK), which is the “knowledge about health, the body, and its (mal-) functioning” [23]. It includes knowledge about the use of carbohydrates and how carbohydrates are metabolized in the body, the mechanisms and risk factors that lead to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, and the impact of type 2 diabetes on health. This knowledge might especially influence the evaluation of susceptibility and severity of coming down with type 2 diabetes (perceived health threat). Moreover, it influences the following knowledge types.

- Action-related Health Knowledge (AK) is the “knowledge about possible actions to preserve functioning and prevent malfunctioning of body and health” [23]. It includes knowledge about recommendations about sugar intake, about foods that contain carbohydrates and sugars, and knowledge about actions to reduce the intake of sugar. This knowledge is hypothesized to influence the attitude towards health action.

- Effectiveness Health Knowledge (EK), which is the knowledge about the relative potential of actions that lead to the desired prevention of diseases [23]. It includes, e.g., the ability to decide on foods that contain less sugar. This knowledge is hypothesized to influence the attitude towards the health outcome.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO/World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data: Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD). Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/en/ (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- UN/United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 3: Ensure Healthy Lives and Promote Well-Being for All at All Ages. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg3 (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Forouhi, N.G.; Wareham, N.J. Epidemiology of diabetes. Medicine (Abingdon) 2014, 42, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO/World Health Organization. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Fensham, P.J. Preparing Citizens for a Complex World: The Grand Challenge of Teaching Socio-scientific Issues in Science Education. In Science|Environment|Health. Towards a Renewed Pedagogy for Science Education; Zeyer, A., Kyburz-Graber, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data: Risk Factors. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/en/ (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Afshin, A.; Alexander, L.T.; Anderson, H.R.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Biryukov, S.; Brauer, M.; Burnett, R.; Cercy, K.; Charlson, F.J.; et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.; Dannemann, S.; Gropengießer, I.; Heuckmann, B.; Kahl, L.; Schaal, S.; Schaal, S.; Schlüter, K.; Schwanewedel, J.; Simon, U.; et al. Entwicklung eines Modells zur reflexiven gesundheitsbezogenen Handlungsfähigkeit aus biologiedidaktischer Perspektive [Development of a model for reflexive health-related ability to act from a biology didactic perspective]. Biol. Unserer Zeit 2019, 49, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Bray, F.; Ilbawi, A.; Soerjomataram, I. Effect on longevity of one-third reduction in premature mortality from non-communicable diseases by 2030: A global analysis of the Sustainable Development Goal health target. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1288–e1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesalski, K.; Bischoff, S.C.; Pirlich, M.; Weimann, A. (Eds.) Ernährungsmedizin [Nutritional Medicine]; Georg Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Renz-Polster, H.; Krautzig, S. (Eds.) Basislehrbuch Innere Medizin [Basic Textbook Internal Medicine]; Urban & Fischer: München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO/World Health Organization. Jakarta Declaration on Leading Health Promotion into the 21st Century. 1997. Available online: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/milestones_ch4_20090916_en.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- WHO/World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data: Unhealthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/unhealthy_diet_text/en/ (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Zeyer, A.; Dillon, J. Science|Environment|Health—The emergence of a new pedagogy of complex living systems. Discip. Interdiscip. Sci. Educ. Res. 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyer, A. A Win-Win Situation for Health and Science Education: Seeing Through the Lens of a New Framework Model of Health Literacy. In Science Environment Health. Towards a Renewed Pedagogy for Science Education; Zeyer, A., Kyburz-Graber, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 147–173. [Google Scholar]

- Zeyer, A.; Dillon, J. Science|Environment|Health—Towards a reconceptualization of three critical and inter-linked areas of education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2014, 36, 1409–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology. Report of the 2000 Joint Committee on Health Education and Promotion Terminology. Am. J. Health Educ. 2001, 32, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.; Bauer, D. The Role of Science Education in Decision Making Concerning Health and Environmental Issues. In Science|Environment|Health—Towards a New Science Pedagogy of Complex Living Systems; Zeyer, A., Kyburz-Graber, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Accepted.

- Malmberg, C.; Urbas, A. Health in school: Stress, individual responsibility and democratic politics. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, C.; Urbas, A. Health and Sustainable Development Education—A Paradox of Responsibility. In Science|Environment|Health—Towards a New Science Pedagogy of Complex Living Systems; Zeyer, A., Kyburz-Graber, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, Accepted.

- Lee, T.D.; Gail Jones, M.; Chesnutt, K. Teaching Systems Thinking in the Context of the Water Cycle. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 137–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.; Arnold, J.; Kremer, K. Consumption-Intention Formation in Education for Sustainable Development: An Adapted Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.C. An integrated model of decision-making in health contexts: The role of science education in health education. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2018, 40, 519–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health Promotion Glossary. Health Promot. Int. 1998, 13, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Røysamb, E.; Rse, J.; Kraft, P. On the structure and dimensionality of health-related behaviour in adolescents. Psychol. Health 1997, 12, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, J.; Roessel, J. Das Ernährungsverhalten Jugendlicher im Kontext ihrer Lebensstile. Eine empirische Studie [The Nutritional Behaviour of Young People in the Context of Their Lifestyles. An Empirical Study]; Bundeszentrale für Gesundheitliche Aufklärung: Köln, Germany, 2003; p. 145. [Google Scholar]

- Mensink, G.B.M.; Kleiser, C.; Richter, A. Was essen Kinder und Jugendliche in Deutschland? Ausgewählte Ergebnisse des Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS) [What do children and young people eat in Germany? Selected results of the Child and Adolescent Health Survey]. Ernährung 2007, 1, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO/FAO/Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on Diet Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. 2003. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42665/WHO_TRS_916.pdf;jsessionid=106E0A600548C07A603F24A196039F44?sequence=1 (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; French, S. Individual and Environmental Influences on Adolescent Eating Behaviors. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, S40–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, L.; Schulz, P.J.; Nakamoto, K. Differential effects of health knowledge and health empowerment over patients’ self-management and health outcomes: A cross-sectional evaluation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 89, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. Modeling Health Behavior Change: How to Predict and Modify the Adoption and Maintenance of Health Behaviors. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour is Alive and Well, and not Ready to Retire: A Commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 9, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, an the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In Social Psychology: A Source Book; Cacioppo, J.T., Petty, R.E., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change1. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, R. Self-Efficacy in the Adoption and Maintenance of Health Behaviors: Theoretical Approaches and a new Model. In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action; Schwarzer, R., Ed.; Hemisphere Publishing Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 217–243. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, S. Stage Theories of Health Behaviour. In Predicting Health Behaviour; Conner, M., Norman, P., Eds.; Open University Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- The Information Centre. Health Survey for England 2007: Summary of Key Findings; The Information Centre: Leeds, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gazmararian, J.A.; Williams, M.V.; Peel, J.; Baker, D.W. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ. Couns. 2003, 51, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. Creating Spaces for Rethinking School Science: Perstpectives from Subjective and Social-Relational Ways of Knowing. In Science|Environment|Health. Towards a Renewed Pedagogy for Science Education; Zeyer, A., Kyburz-Graber, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Keselman, A.; Hundal, S.; Smith, C.A. General and Environmental Health as the Context for Science Education. In Science|Environment|Health. Towards a Renewed Pedagogy for Science Education; Zeyer, A., Kyburz-Graber, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, A. Nutrition knowledge and food consumption: Can nutrition knowledge change food behaviour? Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 11, S579–S585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.; Chai, W.; Albrecht, J.A. Relationships between nutrition-related knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior for fifth grade students attending Title I and non-Title I schools. Appetite 2016, 96, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanjevec, S.; Jerman, J.; Koch, V. Nutrition knowledge in relation to the eating behaviour and attitudes of Slovenian schoolchildren. Nutr. Food Sci. 2013, 43, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.C.; Beckford, S.E. Nutritional Knowledge and Attitudes of Adolescent Swimmers in Trinidad and Tobago. J. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissen, A.R.; Policastro, P.; Quick, V.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Interrelationships among nutrition knowledge, attitudes, behaviors and body satisfaction. Health Educ. 2011, 111, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronk, I.; Kullen, C.; Burdon, C.; O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeyer, A.; Álvaro, N.; Arnold, J.; Benninghaus, J.C.; Hasslöf, H.; Kremer, K.; Lundström, M.; Mayoral, O.; Sjöström, J.; Sprenger, S.; et al. Addressing Complexity in Science|Environment|Health Pedagogy. In Contributions from Science Education Research, Selected Papers from the ESERA 2017 Conference; McLoughlin, E., Finlayson, O., Erduran, S., Childs, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Ecological Behavior’s Dependency on Different Forms of Knowledge. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 52, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyer, A. Getting Involved with Vaccination. Swiss Student Teachers’ Reactions to a Public Vaccination Debate. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieß, W.; Mischo, C. Entwicklung und erste Validierung eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung des systemishcen Denkens in nachhaltigkeitsrelevanten Kontexten [Development and first validation of a questionnaire to capture systemic thinking in sustainability relevant contexts]. In Kompetenzen der Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung: Operationalisierung, Messung, Rahmenbedingungen, Befunde; Bormann, I., de Haan, G., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures 2012, 4, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erduran, S.; Dagher, Z.R. Reconceptualizing the Nature of Science for Science Education—Scientific Knowledge, Practices and Other Family Categories; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman, N.G.; Abd-El-Khalick, F.; Bell, R.L.; Schwartz, R.S. Views of Nature of Science Questionnaire: Toward Valid and Meaningful Assessment of Learners’ Conceptions of Nature of Science. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2002, 36, 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facione, P.A. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction—Executive Summary. Insight Assessment. 1990. Available online: http://www.qcc.cuny.edu/SocialSciences/ppecorino/CT-Expert-Report.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Rafolt, S.; Kapelari, S.; Kremer, K. Kritisches Denken im naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht—Synergiemodell, Problemlage und Desiderata [Critical thinking in science teaching—synergy model, problems and desiderata]. Z. Didakt. Nat. 2019, 25, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | No. of Items | Cronbach’s α | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Health Knowledge (SK) | 15 | 0.92 | What is sugar? What are the symptoms of type 2 diabetes? Why does my body need sugar? |

| Action-related Knowledge (AK) | 15 | 0.94 | What can I do to prevent type 2 diabetes? How can I reduce my sugar consumption? Which foods contain how much sugar? |

| Effectivity Knowledge (EK) | 4 | 0.86 | What is the likelihood that my sugar consumption will cause me to develop type 2 diabetes? What is the probability that I will develop type 2 diabetes if I reduce my sugar consumption? |

| Question | Scale | Importance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||

| How is sugar structured? | SK | 3.02 | 1.31 |

| What is sugar? | SK | 3.23 | 1.23 |

| Why does my body need sugar? | SK | 3.49 | 1.19 |

| What types of sugar are there? | SK | 3.52 | 1.17 |

| How is sugar processed in a healthy body? | SK | 3.57 | 1.18 |

| How effective are individual low-sugar alternatives to prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes? | EK | 3.65 | 1.16 |

| Which organs of my body are involved in sugar processing? | SK | 3.69 | 1.10 |

| Where can I find information on the sugar content of foods? | AK | 3.78 | 1.16 |

| Which types of sugar should I consume preferably? | AK | 3.8 | 1.09 |

| Are all sugars equally harmful? | AK | 3.88 | 1.13 |

| What influences my blood sugar level? | SK | 3.89 | 1.08 |

| How much sugar can I eat every day to stay healthy? | AK | 3.89 | 1.08 |

| How is sugar processed in the body if you have type 2 diabetes? | SK | 3.89 | 1.08 |

| What is the probability that I will develop type 2 diabetes if I reduce my sugar consumption? | EK | 3.90 | 1.08 |

| Which foods contain the least amount of sugar? | AK | 3.91 | 1.18 |

| To what extent should I reduce my sugar intake to prevent type 2 diabetes? | AK | 3.94 | 1.05 |

| What is the likelihood that I will develop type 2 diabetes if I reduce my sugar intake? | EK | 3.96 | 1.16 |

| What are the alternatives to sugar? | AK | 3.96 | 1.21 |

| What is the likelihood that my sugar consumption will cause me to develop type 2 diabetes? | SK | 3.96 | 1.10 |

| What role does sugar play in the development of type 2 diabetes? | SK | 3.96 | 1.03 |

| What are the consequences of type 2 diabetes for me and my well-being? | SK | 4.02 | 1.11 |

| Which foods contain how much sugar? | AK | 4.04 | 0.97 |

| Which foods contain the most sugar? | AK | 4.06 | 1.14 |

| What low-sugar alternatives are there? | AK | 4.06 | 1.13 |

| How can I reduce my sugar consumption? | AK | 4.09 | 1.10 |

| What are the consequences of reducing my sugar intake for my body? | EK | 4.09 | 0.95 |

| What types of sugar should I avoid? | AK | 4.10 | 1.02 |

| How high is my current sugar consumption? | AK | 4.12 | 1.03 |

| How does type 2 diabetes develop? | SK | 4.22 | 0.99 |

| What are the symptoms of type 2 diabetes? | SK | 4.22 | 1.07 |

| Which foods should I consume, preferably, and which should I consume in moderation to reduce my sugar intake? | AK | 4.24 | 1.05 |

| What is type 2 diabetes? | SK | 4.27 | 1.00 |

| What can I do to prevent type 2 diabetes? | AK | 4.27 | 0.99 |

| What are the causes of type 2 diabetes? | SK | 4.31 | 0.97 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnold, J.C. The Importance of Different Knowledge Types in Health-Related Decisions—The Example of Type 2 Diabetes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083396

Arnold JC. The Importance of Different Knowledge Types in Health-Related Decisions—The Example of Type 2 Diabetes. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083396

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnold, Julia Caroline. 2020. "The Importance of Different Knowledge Types in Health-Related Decisions—The Example of Type 2 Diabetes" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083396

APA StyleArnold, J. C. (2020). The Importance of Different Knowledge Types in Health-Related Decisions—The Example of Type 2 Diabetes. Sustainability, 12(8), 3396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083396