1. Introduction

Climate change is frequently addressed as a natural science phenomenon, as this is the field that provides a basis for its understanding. However, climate impacts do not operate in a neutral social field, but in one structured by power relations.

In this sense, the study is framed in the political ecology field, where it has been revealed that there are socio-political, cultural, and affective components that influence the response to climate change, which, if ignored, can put at risk the effectiveness of mitigation and adaptation policies, and contribute to maintaining inequality gaps [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Thus, along with more sophisticated atmospheric models that warn us about climate scenarios, analytical approaches accounting for the socio-political process shaping the climate agenda are also required.

The aim of this work is to show an analytical route to reveal the terms in which climate change is explained, the knowledge that is privileged, the type of actions that are promoted, the positions in the decision making process, the inclusion of women, and the gender agenda in the climate policy, as well as the narratives offered to imagine a common future. It is through this process that ecological phenomena acquire meaning and become important; they constitute the filters through which social action unfolds in response to an environmental problem.

This knowledge is necessary to help guide the mitigation and adaptation strategies within a justice framework. Accordingly, this work seeks to answer the following questions: What are the socio-political and cultural mechanisms that shape the climate agenda? and What is required to guide the climate agenda towards a sustainable and just path?

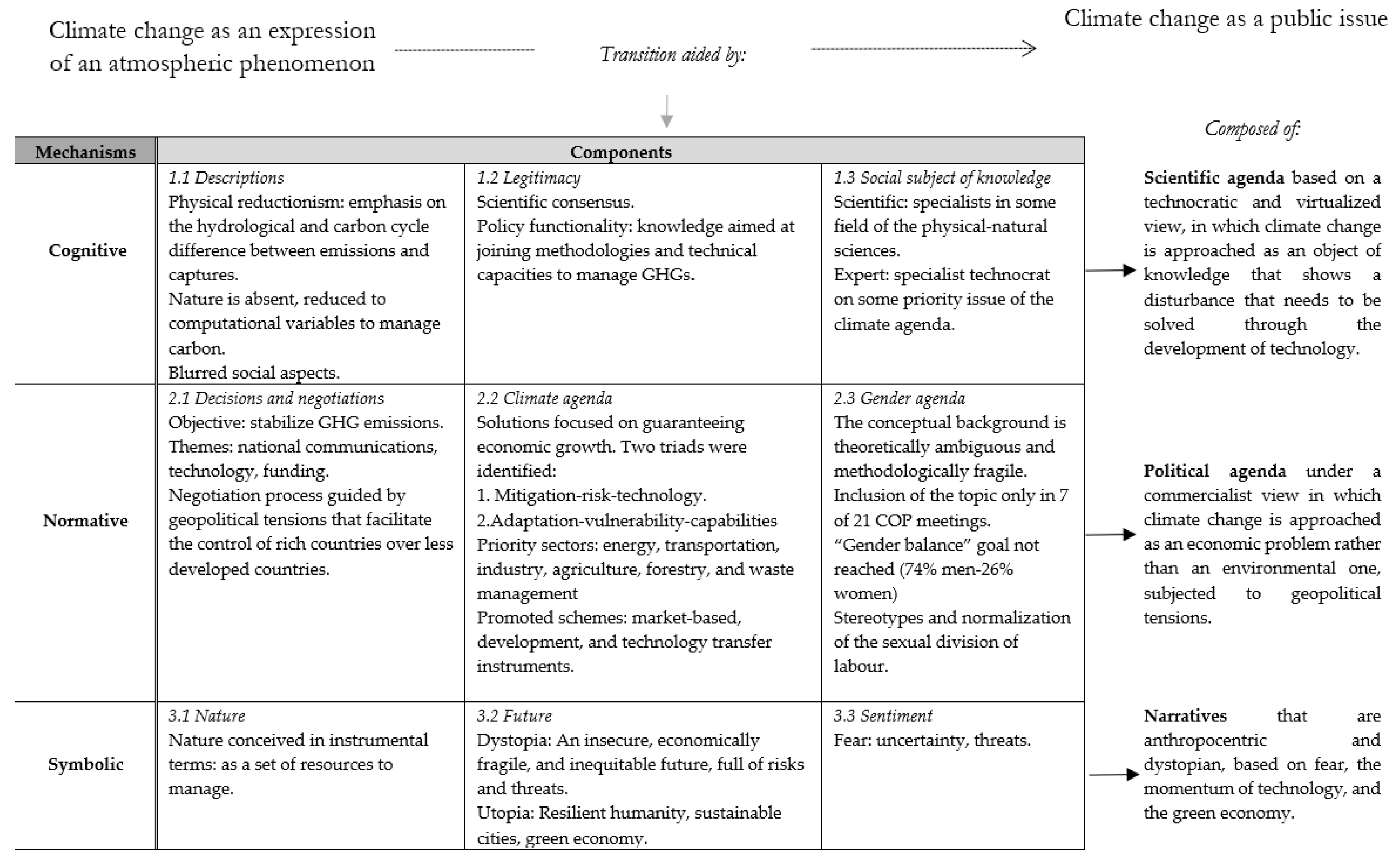

To answer these questions, the discourse from the main international organizations in charge of producing knowledge and agreements regarding climate change was studied. When identifying the cognitive, political, and cultural components of this discourse, a transition between the climate phenomenon and its construction as a public agenda issue was found. This transition was mediated by cognitive operations and the creation of regulations and codes of meaning in which a catalog of explanations and solutions in line with the current socio-economic and political system was developed.

This lays down the conditions for the reproduction of inequality at all levels, as observed when introducing a gender perspective to analyze the terms in which the role of women is conceived, finding stereotyped formulations that help entrench sexual division of labor.

In brief, this analysis empirically supports the importance of including in the debate and reflection on climate change, specific criteria allowing for the operation of public policy within a framework of justice, in particular: knowledge and interests not aligned with a utilitarian view of nature, proposals for alternative development, the generation of methodologies to assess the connection between climate change and the exercise of rights, and inclusion mechanisms that guarantee equal participation.

2. Materials and Methods

This research used a qualitative approach to meet the criteria ensuring the validity of its results. This section displays the epistemological position from which the analysis was performed, the method on which it was based, the instrument used, and the corpus studied.

2.1. Epistemological Approach: The Social Construction of Nature

It is widely recognized that climate change has anthropogenic causes; it is a phenomenon produced by human activities associated with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It has also been pointed out that climate impacts put at risk the possibility of achieving Sustainable Development Goals, which requires articulating adaptation and mitigation policies within a human rights framework. However, it has rarely been approached as a social construct, that is, as an object of knowledge crossed by tensions between various actors, interests, and perspectives.

To design an analysis route with this focus, classic works showing the components—political, cultural, social, and emotional—involved in the social construction of nature, which give meaning to, and legitimize environmental management practices, were reviewed [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

It is important to note that referring to the social construction of nature does not imply ignoring its biophysical elements or denying its operating dynamics. The point is that nature is not comprehended in a transparent and direct manner, but rather, as a result of contingent social practices that, to make the experience intelligible, invariably give it some meaning [

6]. In this epistemological approach, the social aspect constitutes a filter—made up by norms, symbols, and rules of knowledge—through which certain ecological conditions surface as socio-political problems.

In this context, this work started by recognizing that climate change is an ongoing phenomenon, but it did not look to study its causes, effects, or the efficacy of climate policy. The interest lay in showing the process through which it was defined as a problem and the logic that underlies the strategies promoted as a solution. In summary, it studies the construction of climate change as a political and knowledge object, and the way parameters for action were established during this process.

2.2. Methodological Approach and Corpus

The methodological strategy consisted of a discourse analysis, which was also used in the research line proposed by Hajer: “Discourse is here defined as specific ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categorizations that are produced, reproduced, and transformed in a particular set of practices and through which meaning is given to physical and social realities” [

8] (p. 44).

The discourse from international institutions responsible for producing knowledge and agreements regarding climate change—specifically, documents prepared in the context of the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—was taken as an analysis unit. These reports were selected because they condense the decisions impacting the design of climate policies, and because they make it possible to identify the topics prioritized in the debate and the agents taking part in the discussion. On the other hand, the Fifth Assessment Report from the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) was studied because it is the official source of knowledge that feeds climate policy. Additionally, legal instruments with climate change as the main object were also selected, given that they establish rules to understand and address climate change. In summary, the selection criteria were documents including information that expresses the political, cognitive, and regulatory mechanisms shaping the official climate agenda at the international level. Therefore, the institutional discourse emerges as a key field to analyze the way in which climate change is constructed as a public issue and how, in responding to the ecological problem, new social challenges appear. (In addition, to expand the understanding of the social-political construction process of climate change, it would be important to analyze different actors and agendas offering alternative or complementary responses to the hegemonic vision of climate policy, including discourses of other organizations of the United Nations System -for example: International Union for Conservation of Nature, United Nations Development Programme-, as well as other social organizations like Global Alliance Against REDD, Friends of Earth, Greenpeace, just to mention some. Although this is a task I intend to focus on in future, it is beyond the scope of this study, which aims to analyze the institutional perspective that shape the official agenda.).

Specifically, the first 20 years of climate policy were studied as they laid the foundations for the agenda. This period represents an antecedent—or, it could be said, a first phase—that culminated in the Paris Agreement (2015) from which a greater commitment from the Parties involved is expected to carry out actions limiting global warming to 1.5 °C (above pre-industrial levels), in order to achieve sustainable development with low carbon emissions. A study of the period prior to the Paris Agreement is important because it offers an empirical analysis that will allow us to observe, through subsequent comparative studies, whether there is indeed a change in the logic with which the climate agenda is being constructed.

The studied corpus is entirely composed of gray literature produced by these institutions, including documents that initially appear to be neutral, as their contents tend to be developed in technical, scientific, and administrative terms. However, when approaching them from a constructionist perspective, it is possible to show clearly what is usually implicit in these discourses: values, political projects, and conceptions about nature. Specifically, 47 documents were analyzed as follows (

Table 1):

Altogether, this discourse forms a proper empirical basis to account for the process of constructing climate change as a political problem, and to analyze how, in its current form, conditions for the reproduction of inequality are established in the climate agenda.

2.3. Instrument: Axes and Codes for the Analysis

To identify the components influencing the socio-political construction of climate change, the three axes of analysis proposed by Eder [

9] were taken as the basis of this study and specific codes were designed to identify the socio-political and cultural mechanisms that shape the discourse as shown in

Table 2. (Based on this analytical approach, climate policy in Mexico was also analyzed in another work [

11].).

Each document was reviewed using these codes as a filter for analytical systematization. The NVivo program, designed to work with unstructured qualitative data, fulfilled this purpose. The use of this instrument allowed us to identify the patterns that underlie the discourse contained in the documents.

3. Results: Analysis of Climate Discourse

It was found that the socio-political construction of climate change went through discursive processes through which a political and scientific agenda was institutionalized. The terms in which the phenomenon is described, the kind of knowledge favored, the people invited to participate, the type of actions promoted, the positions that emerged during the decision-making process, the inclusion strategies for vulnerable groups, and the narratives and representations feeding the discourse, work as mechanisms through which the climate phenomenon is translated into a public issue. In their interaction, these components shape the conception of the problem and the answers considered appropriate, establishing conditions for action through the design of rules, the legitimization of practices, and the use of benchmarks of meaning.

In this process, climate policy is formulated following an anthropocentric, technocratic, market-based, and virtualized vision of socio-ecological relations, consolidating an agenda aimed at protecting the current socio-economic system. Concerning gender, it was found that the inclusion of women is associated with the domestic field, carrying out stereotypical roles, and that equal participation in spaces where climate policy is developed is far from being achieved.

The results obtained are outlined below in

Figure 1, and further on, the analysis is broken down by each of the studied axes.

3.1. Cognitive Axis

The elements used to describe climate change, the criteria by which the produced knowledge is legitimized, and the type of social subjects called to participate in this process were analyzed in this axis. The results are displayed in detail.

3.1.1. Descriptions

It was observed that climate change, as an object of knowledge, is supported in a cognitive scaffolding to manage the carbon cycle and account for the effectiveness of the actions. This scaffolding was structured in the following stages: an explanation of climate dynamics, statement of causes, inventory of effects, projection of scenarios, and design of actions to avoid them.

A large part of the knowledge generated is expressed in concepts such as models, trajectories, emission scenarios, baseline, carbon cycle, mitigation, and adaptation. The cognitive scaffolding was established in such a way as to allow for the promotion of a specific action agenda, formulating a technocratic approach to the problem.

It is worth noting that an anthropocentric and utilitarian view was present in the analyzed corpus. This is so because nature or the conservation of natural resources is of interest in the sense that it fulfills a function in the satisfaction of human needs or in capturing GHGs. Nature is being reduced to indicators and variables entered into computational models to explain and anticipate climate dynamics, thereby moving from an analog conception of socio-environmental relations to a more virtual one, in which carbon management is the basis for thought and action.

There is a kind of “physical reductionism” [

6] in the way of understanding the climate phenomenon, as explanations revolve around the carbon cycle and gas properties, and how these are produced, the methods used for measuring them, the ways to capture them, and the instruments verifying the effectiveness of actions. Despite recognizing the anthropogenic origin of climate change, the social aspect is frequently approached in an overly simplistic manner, usually associated with vulnerability, adaptation, risk, and uncertainty. These concepts give way to a narrative inviting us to build capacities and issue national communications that include data on macroeconomic indicators, demographic profiles, infrastructure profiles, and productive sector profiles.

Thus, a cognitive basis is established which, by defining the causes in physicochemical terms (disassociating practices with a high carbon footprint from the socio-political and economic contexts that produce them), finds in technological development the ideal route to address the problem. From this perspective, it is not necessary to promote changes in the socio-economical order or in the production, distribution, and consumption practices this order is based on. Nor has a political analysis of the agents (countries or companies) that influence the construction of the climate agenda according to their interests been performed. This knowledge, of a more sociological nature, is as relevant as that generated by natural sciences to build a climate policy with the potential to mitigate the causes of the phenomenon and advance towards a horizon of sustainability.

3.1.2. Legitimacy

It was found that knowledge can be legitimized in two ways: from inside the scientific field through consensus, and through the role given to that knowledge in the political field for intervention. Regarding the first point, mathematical modeling is one of the most frequently used methods for generating knowledge and projections. Its results are validated through a consensus process in which knowledge is legitimized, creating a core of hypotheses and scenarios expressed in terms of confidence, agreement, and probability.

Thus, in the face of the uncertainty posed by a phenomenon that cannot be fully captured using the instruments currently available, a collective construction of knowledge emerged as a strategy to build trust. Such a mechanism was institutionalized through the creation of the IPCC.

The second way of legitimizing knowledge is through the practical utility it provides. In this way, specific functions in the political field are assigned to the knowledge generated; the following were identified:

Action justification: in the analyzed discourse, science promotes actions that are bold, immediate, courageous, and determined. A codependent relationship between science and politics was observed in which the latter constantly relies on the former to legitimize a specific agenda. Science, in turn, is promoted—i.e., funded and instituted—by political decisions which may influence the selection of the themes or methods prioritized. (This result is in agreement with the work of Demeritt [

6], in which he analyzes scientific practices in climate modeling.).

Standardization: this function forms a uniform body of data worldwide. To achieve this, the development of national communications, reports, GHG emission inventories, and guidelines for adaptation and mitigation is promoted. These tools shape a perspective to understand and deal with the phenomenon, establishing a base to elaborate diagnoses and guide actions. Many issues are left out, with social inequality being chief among them. There is no information on how inequality is included in reproduction, production, distribution, and consumption practices, nor on how it can be affected by adaptation or mitigation strategies.

Environmental management: this type of knowledge encourages or controls environmental practices through instruments used for measuring, reporting, verifying, monitoring, and evaluating. Even though assessments are carried out with a “nonintrusive, nonpunitive, and respectful of national sovereignty” approach, they exercise a certain degree of control, given that certain ways of relating to the natural system are encouraged by granting resources for activities deemed appropriate to fight global warming.

Training: Personnel are trained in the methodologies to carry out assessments and technical training in different countries, encouraging national policies to meet the criteria established at the international level. Training serves to spread information and create expert groups that reproduce a perspective on the understanding of climate change and the appropriate responses to address it.

This analytical exercise does not intend to assert that the knowledge produced about climate change is invalid. However, it does stress that the ways of legitimizing it are not based on a sterile scientific method, but that consensus and politics are embedded in scientific practice and in how results are legitimized.

3.1.3. Social Subject of Knowledge

Knowledge is produced by social subjects, that is, individuals placed in the social structure based on their gender, class, nationality, ethnicity, age, etc., qualities that shape their worldview, in accordance with a belief system from which they produce knowledge of all kinds. In the case of climate knowledge, it was found there are two types of social subjects recognized as possessing agency within this process: the scientist, particularly those with specialized training in the field of natural sciences, and the experts, with specialized training on the development of technologies, development planning, or the application of methodologies designed in the context of climate policy. This has two effects: only certain topics are valid, and only some people can participate in a debate framed in these terms.

Scientific productions go through a process of selection and peer-evaluation before being integrated into the institutional debate, a process managed by the IPCC, which invites the Parties to send candidates who stand out for their publications on a subject related to climate change. And, although the need to broaden the spectrum of participants is recognized, no mechanisms to include people without scientific credentials were identified, leaving out knowledge that is not formulated in terms of the conventional scientific paradigm.

Contributions from those who practice physicochemical sciences are undoubtedly essential for understanding climate system dynamics. However, prioritizing this type of approach establishes conditions for the exclusion of other knowledge not formulated in terms of the conventional scientific paradigm, but that shapes perspectives and exposes interests and visions that might well enrich the climate agenda.

On the other hand, this process is not gender neutral. There are sociocultural constraints that result in low participation of women in the scientific fields which are given the most voice. Thus, although there is no open position against their participation, there are no affirmative action mechanisms to promote parity in the construction of climate knowledge, as has been pointed out in other works [

12].

3.2. Normative Axis

The elements used to design the institutional agenda against climate change were analyzed in this axis, particularly the decisions taken within the framework of the COP, the proposed actions, and how gender is approached.

3.2.1. Decisions and Negotiations

Among the central themes present in the COP body of decisions, the following stand out: encourage the development of mitigation policies, request for national communications to be sent to inform on the progress of countries regarding the commitments assumed, promote the development of risk management policies in extreme weather events, and boost financing for the development and transfer of technology.

These technical-administrative measures are usually stated in such general terms that they appear to be neutral. However, they are the result of negotiations by national agents who operate in the field of climate policy from unequal positions, determined on the basis of economic criteria that classify countries according to their degree of development. Specifically, the economic position of the countries stands out as the factor that modulates who can define the type of solutions and who should implement them: “rich countries” recognize their responsibility in atmospheric warming, so they offer to finance “less developed countries” to implement a climate policy, which must meet the criteria and requirements stipulated in the negotiations, a field in which “rich countries” have greater decision-making power. (This work used adjectives that qualify countries as: rich, poor, developed, underdeveloped, and so on. This follows how they are enunciated in the analyzed discourse. These definitions in themselves have a symbolic significance, which cannot be fully discussed at this time.)

Thereby, a vertical formula surfaces, which can be translated into a control mechanism over peripheral countries in at least two ways: conditions to regulate socio-environmental policies and practices in the local sphere are created in the international sphere, while the financing received is often granted in the form of credit, adding to the national debts of the “least developed countries.” In this way, conditions to maintain gaps in political and economic inequality between countries are established, undermining the autonomy of the less privileged. This situation does not contribute to decreasing social or ecological vulnerability.

3.2.2. Action Agenda

Regarding the set of promoted solutions, it was observed that these are organized in two triads: mitigation is associated with risk, and addressed through technological development, while adaptation is associated with vulnerability, for which the development of institutional capabilities is proposed. The first triad has been developed with greater clarity and range, while the second has been worked on with a more relaxed and ambiguous approach. Following this logic, the sectors that get a greater degree of attention in climate policy are energy, transportation, industry, agriculture, forestry, and waste management.

The actions proposed in the framework of mitigation can be grouped into the following items: transition to clean and renewable energies, conservation of natural carbon sinks, and economic instruments and mechanisms for clean development. As such, mitigation is conducted in two big areas: technological and commercial. Accordingly, nature is once again reduced to its function as a means to capture carbon or as a less carbon intensive source of energy. (On this point, I would like to thank one of the reviewers of this article for highlighting that “utilitarian views of nature tend not to make economies less energy intensive, but rather make energy less carbon intensive”.).

The establishment of mechanisms, legal instruments, or actions guaranteeing that responses to climate change do not contradict economic growth and that free market is not impeded has recurrently been justified. An example of this kind of position is found in the COP-18, during which it was argued that “measures taken to combat climate change, including unilateral ones, should not constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade.” However, GHG emissions are highly linked to productive activities using fossil fuels or impacting ecosystems that capture carbon. Reducing emissions of these gases involves transforming production and consumption practices, which are invariably linked to the public and private interests of those who profit from them. This question is unavoidable when designing actions against the phenomenon.

Nevertheless, the above was not proposed as a contradiction because technology and market strategies are considered ideal ways to resolve the tension between climate change and economic growth.

Regarding the second triad, the adaptation agenda is so broad that the direction of the strategy is not distinguished clearly, yet certain recurring themes can be identified: national adaptation plans, capacity building, extreme climate events, sustainable management of natural resources, and healthThis agenda is more focused on developing countries.

Even though the importance of promoting “low-carbon lifestyles” is mentioned, there are no specific proposals that suggest what such livelihoods would consist of. In this context, the issue of consumption is poorly addressed. No specific actions, methodologies, or strategies treating this as a central element were identified. Additionally, no paradigms that could help build these models, such as those consistent with the Degrowth theory or “Buen vivir” (Good Living) perspective, have been reconsidered. (These proposals can be found in works such [

13,

14,

15].).

There is no consistency between the severity of the scenarios that arise in the trajectories to climate change adaptation and the actions to respond to them. As the IPCC recognizes in the Fifth Report, there is an imbalance between mitigation and adaptation strategies. It should be noted that the IPCC has pointed out the importance of including in the adaptation strategies issues that have been poorly attended, such as recovering indigenous, local, and traditional knowledge. It is also proposed that governance be established as an institutional framework for adaptation, and not just to rely on a cost-benefit assessment. It is underlined that to achieve these objectives, critical changes will be necessary. It will be important to monitor the progress made in this direction in post-Paris Agreement policies.

But given how the agenda has been constructed in this period, it can be assumed that climate change is being addressed from an economistic perspective. The solutions are aimed at managing emissions through market instruments and at fixing production practices through technological innovations, but without transforming extractive practices which generate both environmental and social problems. Additionally, the objective of economic growth as a guarantee for welfare was not questioned, and no alternatives for conventional ways of thinking and promoting development were proposed; not even sustainability as a model was taken into account.

3.2.3. Gender Agenda

This article started with the interest in distinguishing the sociocultural and political mechanisms involved in the construction of climate change as a public problem. This interest is justified by the need for more information on how conditions under which inequality is maintained—or disrupted—are established during this process. To contribute to this type of study, analyzing how gender is being included in the discourse was useful, given that this is one of the factors that shape large inequality gaps.

First, it was identified that the participation of women in the climate agenda is conceived in stereotypical terms, given that women are shown in two different ways: as vulnerable and virtuous (coinciding with Arora-Jonson results [

16]). The image of vulnerability is associated with a maternal role, and it is said that climate change affects their ability to care for family needs. Concerning their virtuousness, it is said that women are allies in the fight against climate change, considering that, at home, they are usually the ones to commit to activities such as recycling and using green technologies. Examples of their participation, including the use of energy-efficient stoves, the construction of solar panels, the collection of rainwater, reforestation activities, and care for biodiversity, were also listed. Even though there are cases that demonstrate the above, the interpretation of these actions reinforces gender typologies and ignores the socio-economic conditions that sustain these practices, reproducing “ecomaternalist” arguments [

17] used to justify the participation of women in climate policy as long as they fulfill a role for the service of other people. In this sense, it can be argued that women are not only vulnerable to the effects of climate change, but to the way they are inscribed in the climate agenda.

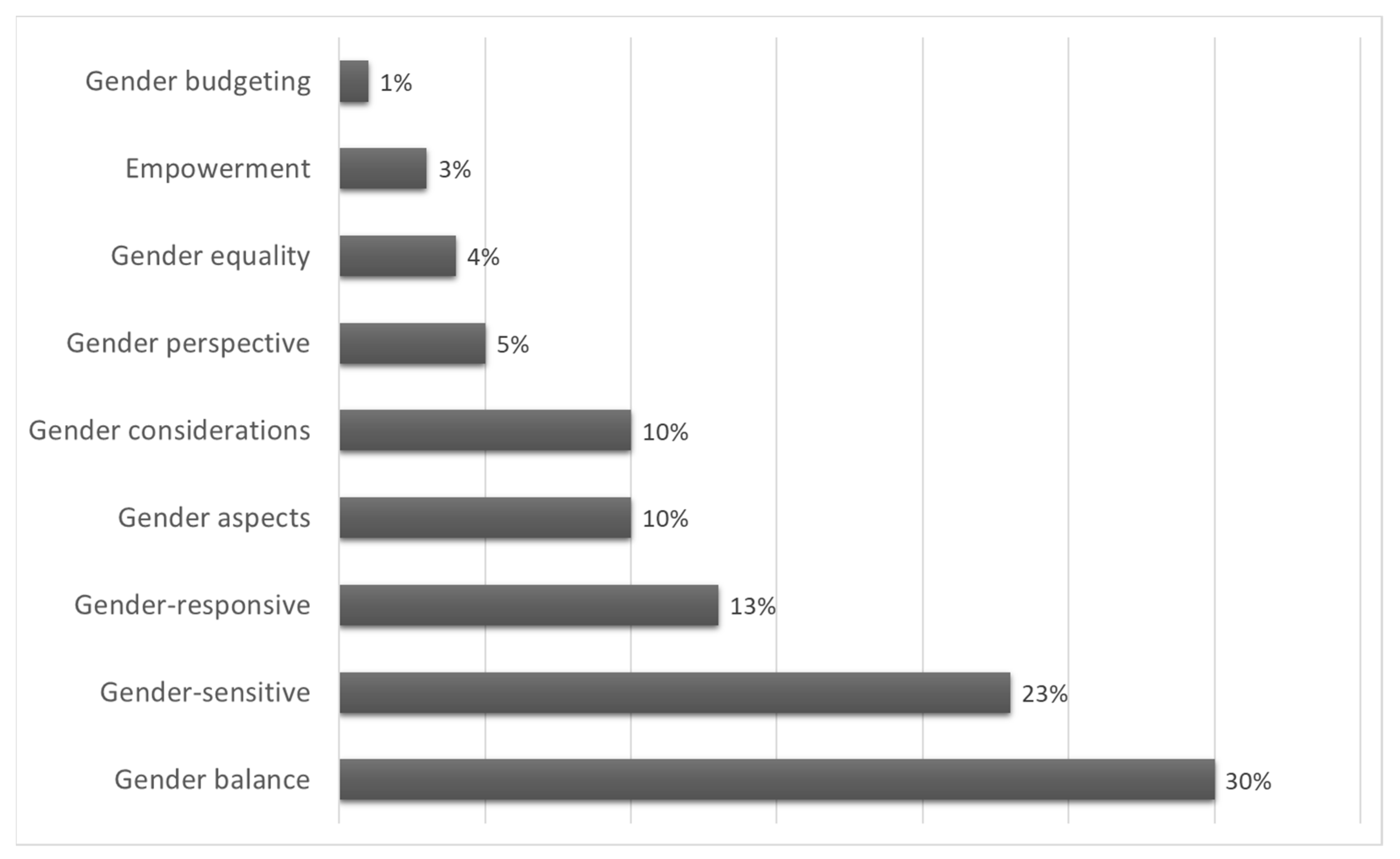

Secondly, to broaden the exploration of this issue, the way the gender concept is incorporated into COP decisions was analyzed by accounting the citations and identifying their content. In an overview, it was found that agreements looking to meet the obligations stipulated in international instruments regarding women’s human rights were reached for only 7 of the 21 COP meetings held until 2015. After reviewing this point in greater detail (

Figure 2), the results showed that attention was focused on increasing the participation of women in climate policy (“gender balance”). This is an important goal, but a greater presence of women does not guarantee a gender perspective in climate policy.

On the other hand, under the designation “gender-sensitive”, the importance of identifying the needs and interests of men and women is pointed out for these to be integrated into climate policy. Measures such as these help to identify gender-differentiated environmental management patterns and form an empirical basis for action. However, this approach has been widely used to incorporate gender in environmental policy for some decades, and it has been insufficient to close inequality gaps.

In this context, the incorporation of the “gender-responsive” approach becomes relevant, which seeks to mainstream gender perspective in climate policy, in order to advance gender equality and attention to women’s rights. Unfortunately, this is not the central strategy in COP decisions, which would imply giving resources for actions in this direction, and the results show that gender budgeting action is hardly incorporated.

It can be argued that in the analyzed period, a lax conceptual baggage was used; at least a fifth of the mentions refer to “gender considerations” or “gender aspects”, words of such generality that they are open to interpretation, and are not usually accompanied of concrete actions. Social objectives such as equality or empowerment are hardly mentioned. In sum, the treatment of this concept is often superficial and does not aim at recognizing structural power relations. It has more of a technocratic function, in the sense that it is useful to justify that a problem calling for attention from the international sphere is being addressed, as shown in other studies [

18,

19].

Even though the goal to reach a “gender balance” has received special attention in those bodies where climate policy is defined, equal participation is not guaranteed. There continues to be a vast participation gap in these spaces: the average for the analyzed period shows that male representation reached 74%, while female representation was 26%. (To obtain this fact, the available information for the studied period, taken from the Gender Composition Reports put together within the framework of the COP, was analyzed.) Over the period studied, women’s participation increased by the years 2013 and 2014, since “Gender Day” events are held, and the Lima Work Programme on Gender was established.

It is noted that incorporating a gender perspective into any public policy is a process; it involves time and effort, and is commonly promoted by organized women. (In this case, the gender incorporation in climate policy was possible thanks to the efforts of various organizations in favor of women’s rights that began working since 1995, and which, in the COP-13 in 2007, joined together to form the Global Alliance on Gender and Climate Change (GGCA). Another important network is Women and Gender Constituency.) In this sense, it can be pointed out that there is a trend both in the increase of women’s participation and gender inclusion in climate policy, but it is important to continue with the efforts so this actually translates into a strengthening of women’s rights, or at least to ensure that climate policy does not contribute to increasing their social vulnerability.

3.3. Symbolic Axis

On this axis, the codes that dynamize sense and meanings in climate discourse were analyzed, highlighting those that refer to the natural system, the future, and the emotional charge.

3.3.1. Nature

As previously mentioned, the concept of nature does not appear very frequently in the analyzed corpus, although it is suggested, exchanged, rationalized, or sublimated. The planet, environment, ecosystems, natural resources, and occasionally Mother Earth were all mentioned in the documents. These documents are dominated by a merely anthropocentric view, assigning a value to nature based on the services it provides to humanity. This logic explains favoring economic interests before ecological ones in responses to fight climate change.

When the “environment” is mentioned, it is accompanied by the concept of sustainability, the frame that has been the basis of the environmental debate for at least the last four decades, a project claiming to articulate social, economic, and environmental goals to achieve development. However, sustainability as a project has very little presence in the climate discourse, as this is not the story used to imagine the future; it is being replaced for narratives of green economy and technological innovation, where the social dimension is blurred.

Conversely, despite recognizing the anthropogenic origin of this phenomenon, the references given to imagine it do not have a human face; instead, the Planet or the Earth is presented as the image of the impact. These formulations are usually associated with the great “human family” that must bridge its differences to take care of its home, appealing to political will and individual commitment.

Another image that refers to nature is that of “Mother Earth.” This is associated with indigenous peoples and climate justice, but it is not usually accompanied by arguments that allow for some rethinking of socio-environmental practices or of the criteria that should be considered to build fair agreements.

3.3.2. Future

The climate narrative is shaped by a commitment to the future, presenting two alternatives: dystopia and utopia. The first one is a lot more prevalent, and invites us to imagine an unsafe and chaotic future, full of risks and threats. In this scenario are “developing countries,” which would face all kinds of catastrophes. Solutions are offered together with the alarmist tone: first, guarantee economic growth, meet mitigation commitments, develop risk management tools, and rely on science and technology. If this agenda is fulfilled, the possibility for a utopian, resilient future, sustained by a green economy and with healthy ecosystems, is unlocked.

In any of these scenarios, the future does not belong to us; it is a place for the next generations, which will be in charge of judging our role in the fight against climate change. This is our great heritage as humanity. As such, although the dystopian and utopian scenarios would seem opposite, they reinforce each other in the argumentative logic of the discourse: in the face of a catastrophic possibility, actions to get a second chance are strongly encouraged, warning that if the provided solutions are not adopted, the climate crisis will ensue and future generations will judge us.

3.3.3. Affective

The analyzed discourse is loaded with an emotional charge in which emotions associated with uncertainty, worry, and threat prevail. These all have fear as their common denominator. Accordingly, Altheide [

20] has indicated that this emotional environment provides the conditions for people to support state policies that promote agendas not necessarily related with the needs of the population, but that manage to resonate because they are paired with deep cultural anxieties.

A discourse that uses these terms may open the way to accepting any solution offered as a safeguard. These can range from those committed to market instruments to more extreme ones, which in themselves are potentially dangerous, including the proposals put forward by geoengineering, which become “hypermasculinized” responses to climate change [

17,

21].

As pointed out by Hajer [

8], a narrative works as a framework; it provides people with a set of symbolic references that delimit the understanding of a phenomenon. In this sense, identifying the narrative thread in climate discourse does not mean ruling the scenarios established by the IPCC as fiction, nor dismissing their usefulness. The idea is rather to consider that since climate change is such a complex phenomenon, dominated almost exclusively by scientists and politicians, it is relevant that the narrative accompanying it is apocalyptic. Fear is not the most adequate place to generate alternatives. Indeed, a discourse given in these terms does not offer conditions for collective and organized action, but can lead to stupefaction, leaving the power to decide in the hands of those who say they know where to lead us to save us from threats.

4. Discussion: Paths towards Sustainability and Gender Justice

This section shows the implications, contributions, and scope of this study. Additionally, it presents a series of proposals to guide the agenda towards a justice framework.

Regarding the first point, this study shows the importance of incorporating sociological approaches and qualitative methods into the study of climate change. The idea is not only to account for risks or adaptation—issues where the said approaches are generally included—but to show how the meanings, values, interests, and visions that shape the understanding of and response to the phenomenon are settled. What was shown here is that climate change is a social construct insomuch that, to turn it into a public issue, it goes through cognitive, normative, and symbolic operations that present the problem in such a way that the current socio-economic order is reproduced, power relations are reinforced at various levels, and socio-environmental relations are legitimized in instrumental terms.

This conclusion does not propose that there is conscious intentionality behind the logic underlying the discourse. Even though the methodological approach used does not allow for causal relations, it does help to note that the terms used to present climate change as a public problem also lay down conditions for the reproduction of inequality at all levels.

Specifically, regarding gender incorporation in climate policy, while the focus is on increasing the presence of women at the COP without questioning the content of the agenda, associating women with the domestic sphere, or typifying them as vulnerable subjects, makes it highly likely that climate policies will reproduce gender inequality, even if this is not the intention. Another type of approach is required which takes into consideration the power exercise in relationships between men and women, and which addresses tensions between the domestic and the productive spheres, placing the ethics of care as a line of reflection. Likewise, when the issue of population growth is treated as a factor affecting climate change, it would be necessary to address it within a sexual and reproductive health rights framework.

In other words, it is necessary to move from a technocratic approach to a sociopolitical one, in which the structures that reproduce women’s subordination are questioned: gender violence, women’s exclusion in decision-making, economic inequality gaps, and the division of labor according to gender.

If not, women’s participation will occur in instrumental terms: they will be considered insofar as they can contribute to adaptation or mitigation strategies, but in a framework that does not treat them as equal human rights holders. Likewise, the climate agenda could benefit from establishing dialogues with critical ecofeminism, opening up to a set of topics that are of interest to women in both the south and the global north: food sovereignty, water rights, pollution, seed management, human security, ethical consumption, and sustainable lifestyles.

Recognizing that climate change is not a phenomenon isolated from other socio-ecological problems, and that, in today’s world, it is not the only source of risks threatening the dignity of life, it could be argued that it is important to not only integrate response capacities, but to do so within a framework of justice and sustainability. To advance this task, the following dimensions—which were initially proposed by some justice theorists [

22,

23], and which can serve as a basis for identifying specific actions so that the climate agenda contributes to expanding the exercise of rights—are reconsidered. Some of those identified are shown in

Table 3:

An agenda like the one presented here can only start from a broad understanding of climate change, i.e., one that recognizes that, if the origin of the phenomenon is anthropogenic, its solution is to build new social agreements. Therefore, it would also be important to increase the presence of social sciences in the generation of knowledge, as well as of participation methodologies that can support this process.

Finally, it is recognized that these results apply to a specific period of climate policy (1995–2015), but studying these first 20 years is important because they established the basis of the agenda. In this sense, the study offers a useful empirical analysis to carry out a comparative analysis to distinguish changes after the Paris Agreement.

5. Conclusions

In brief, in line with the purpose stated at the beginning of this work, a transition between the climate change phenomenon and its construction as a public problem was evidenced. This transition was facilitated by cognitive operations and normative productions associated with symbolic referents, which together function as mechanisms for producing meaning that shape the action framework.

The analyzed discourse showed that climate change, as an object of politics and knowledge, is being constructed in technological, technocratic, and virtualized terms with an anthropocentric and market-based perspective, expressed in a utilitarian conception of nature.

In light of all this, there are conditions favoring the reproduction of the current socio-economic order, the maintenance of inequality gaps, and the promotion of environmental practices in instrumental terms. Accordingly, the pattern used for introducing the subject as a public issue is established, leaving little room to include knowledge and interests that deviate from the established parameters.

Simultaneously, what emerges from this analysis is that the agenda reproduces gender stereotypes and normalizes the sexual division of labour by associating female participation with the domestic space. While there has been progress in incorporating women in the debate, there is still a wide gap in the spaces where climate policy is designed. Likewise, it was demonstrated that gender perspectives in climate agenda are still very fragile, and the importance of moving from a technocratic management to a sociopolitical analysis to guide the climate agenda towards principles such as equality and justice was argued.

Failing to know the sociocultural factors that underlie the design of a political agenda renders invisible the effects it can have on social life, particularly among those groups excluded from the agenda formulating process. In this specific case, the analysis allowed us to show that, even though it is necessary to reach mitigation goals and design adaptation strategies, these need to be integrated with more extensive social objects that guarantee equality, dignity, and inclusion, under narratives that do not displace sustainability for the green economy.

This is why it is necessary to address climate change from a justice approach, taking the framework of rights as the parameter of action and incorporating voices that help to imagine other common paths and projects, and models to relate to nature by recognizing its worth. These issues are as relevant as the stabilization of GHG emissions and, ultimately, represent the most pressing challenges we face due to climate change.