Key Aspects of Leisure Experiences in Protected Wilderness Areas: Notions of Nature, Senses of Place and Perceived Benefits

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nature: History of the Concept and Relationship with Wilderness Protected Areas (WPA)

1.2. The Benefits of Leisure in Protected Wilderness Areas (WPA)

1.3. Sense of Place and Leisure Experience in WPA

2. Materials and Methods

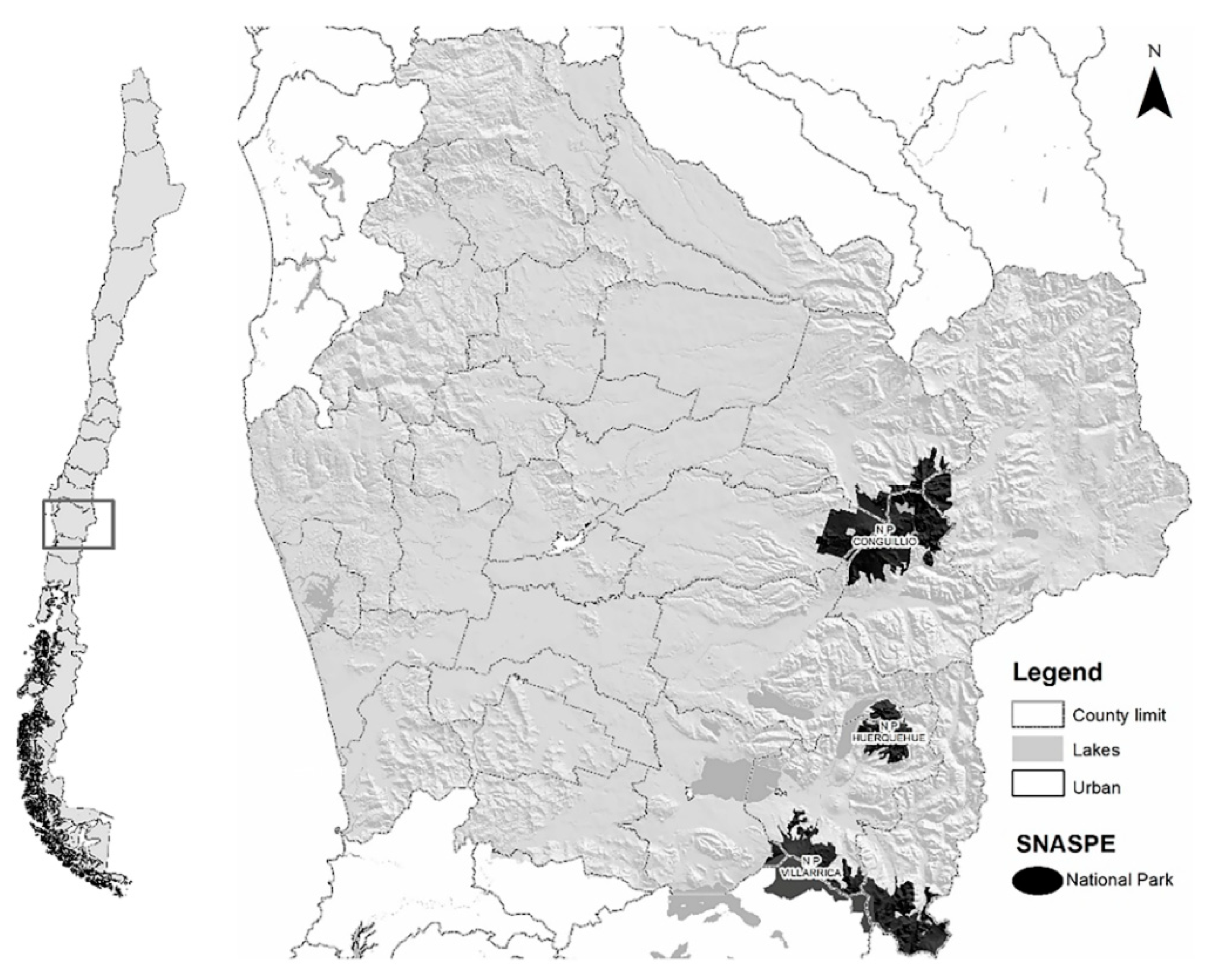

2.1. Area of Study

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Sample

2.4. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Meanings of the Notion of Nature

3.2. Perceived Benefits from Leisure Experiences in WPA

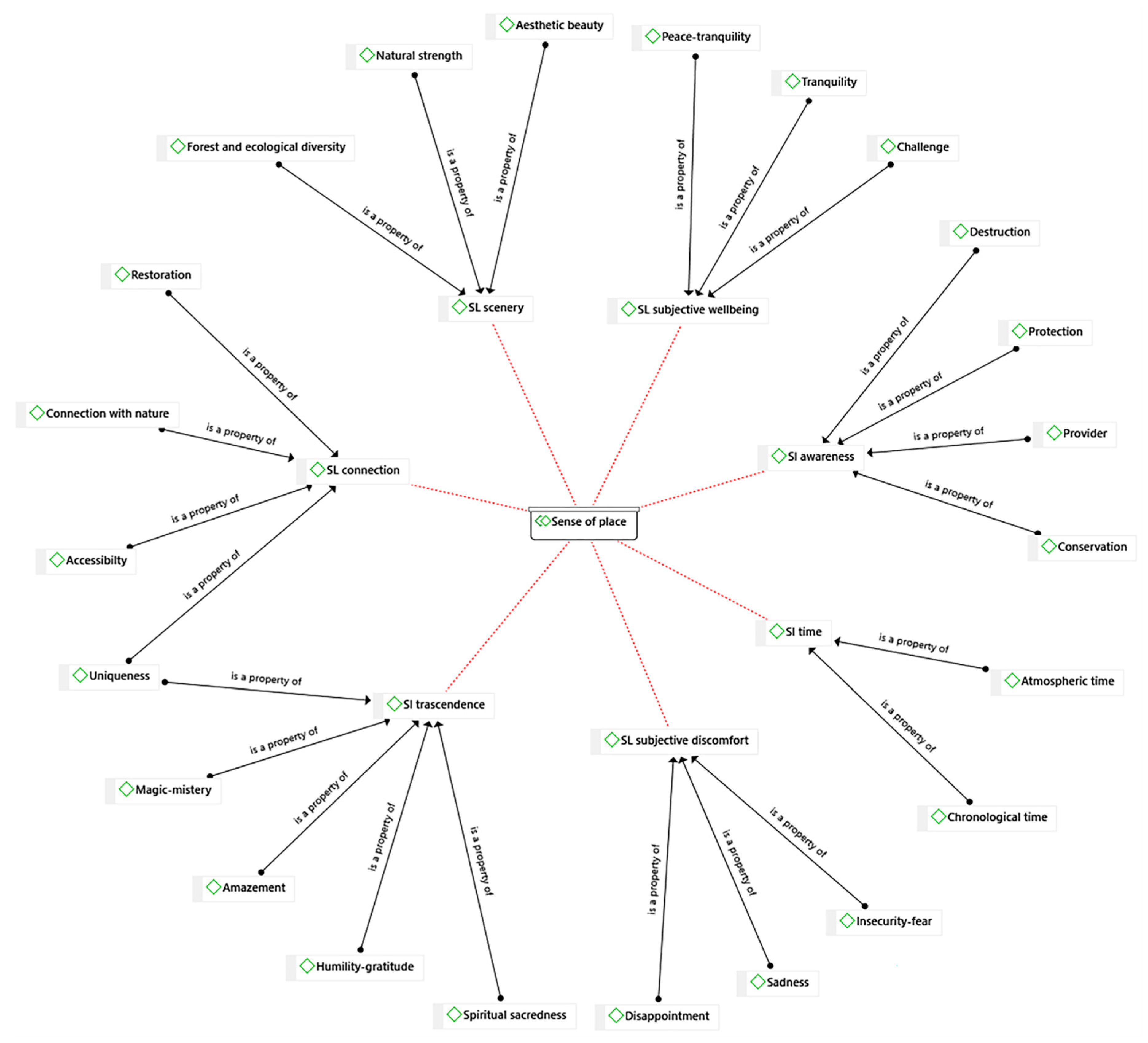

3.3. Sense of Place/Special Places

4. Discussion

- (1)

- The first is what we called “Transcendence” and considers the meaning of “Nature Sanctuary”, the benefit “transcendent emotions”, and the sense of place “Transcendence”. These three families are associated with the quality of transcendence that emerges from the LEWPA. It emerges from participants’ narratives of experiences in non-tangible spiritual planes and in some cases of connection with the divine, a creative force, and full integration with the natural world.

- (2)

- The second super-family is “Perception of Well-being”, constituted by the meaning of Nature “benefits”—physical and psychological benefits—and the sense of place “subjective well-being”. This category reflects the centrality of the perception of well-being associated with the LEWPA, which in principle has a psychological emphasis and to a lesser extent relates the quality of restoration and physical toning attributed to the LEWPA. The predominant discourses of sensation of peace, tranquility, and perception of well-being emphasize the value assigned to the LEWPA as a provider of benefits that are not perceived in the everyday urban world.

- (3)

- The third super-family is denominated as “Connection” and comprises the Meaning of Nature “connection”, and the Sense of place “connection”, and although in the case of the variable Benefits it did not emerge as a family of its own, it is present as a code in virtually all families of that variable. This super-family refers to the quality attributed to the LEWPA of generating, in the first place, a connection with Nature and, to a lesser extent, a connection with oneself and other people. It is considered as a central category and one of the most distinctive of the LEWPA, since it reveals the notion that the WPA embodies Nature in its purest state or in its essence. One of the most relevant aspects of the notion of “connection” is the idea of uniqueness or integration, that is, to feel part of Nature, to be one with the natural world, a feeling that seems only possible to perceive with this intensity in WPA. This could account for both the expectations regarding the experiences that one can have in places already defined as Nature reservoirs, as well as the type of disposition and activities carried out to maintain coherence with the former.

- (4)

- Finally, the super-family “Environmental Awareness” is made up by the meaning of Nature “environmental awareness”, the benefit “educational”, and the sense of place “awareness”. This category highlights the educational property of the LEWPA reflecting the generation of pro-environmental behavior and attitudes in the subjects of the study. Based on the experiences in WPA and their notions of Nature, people become aware of the deterioration that human beings have generated on the planet. It should be noted that the concrete structuring of WPA is already impregnated with an educational and prescriptive sense of taking “care of Nature”. Thus, the mediation of various signs (e.g., “No campfires allowed”, “Dispose of trash at recycling points”, “Do not feed wild animals”) and the presence of environmental education centers, as well as intentional verbal exchanges with Park Rangers, configure a kind of “moral geography” [72] (p. 130) of the place, which determines the visitors’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral aspects. This family also highlights the double dimension of the educational experience, which is valued not only for the learning that is generated on a personal level, but also for the possibility of teaching others and making them aware of planetary deterioration.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Deepening Question | Variable to Analyze |

|---|---|---|

| Your age? | Sociodemographic | |

| Where do you live? | Sociodemographic | |

| Where were you born? | Sociodemographic | |

| Where did you grow up? | Sociodemographic | |

| Do you know the limits of the XXXX National Park? | Sense of place | |

| Could you tell me what kind of practical activities you usually do in the park / in your free time? | Leisure activities | |

| Is there anything that you find rewarding as a result of these activities? | Leisure benefits | |

| Would you recommend this type of experience to your friends or family? | Why? | Leisure benefits |

| Do you share or have you shared this hobby with others? With whom? | Benefits of leisure / place bonding | |

| Tell me how would you describe your relationship with nature. | Could you talk about what that means nature to you? | Notion of Nature |

| In relation to your visit or visits to XXXX National Park. | ||

| Please describe three special places in this park (the description can be made in relation to; the sights, smells, sounds, animals, plants, ruins, buildings, etc.). | Sense of place |

Appendix B

| Profile | Villarrica | Huerquehue | Conguillio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resident who camps in the park | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Resident who does not camp in the park | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| Non-resident who camps in the park | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| Non-resident who does not camp in the park | 2 | 3 | 4 |

References

- Ried, A. La experiencia de ocio al aire libre en contacto con la naturaleza, como vivencia restauradora de la relación ser humano-naturaleza. Polis 2015, 41, 11128. [Google Scholar]

- Bahia, M. “Uma análise crítica das Atividades de Aventura: Possibilidades de uma Prática Consciente e Sustentável”. In Dia a Dia Educacao; 2010. Available online: http://www.educadores.diaadia.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File/2010/artigos_teses/EDUCACAO_FISICA/artigos/Bahia2.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Milton, K. Nature and the environment in indigenous and traditional cultures. In Spirit of the Environment. Religion, Value and Environmental Concern; Cooper, D., Palmer, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; pp. 86–99. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, P. Beyond Nature and Culture; The University of Chicago Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pálsson, G. Human-environmental relations: Orientalism, paternalism and communalism. In Nature and Society, Anthropological Perspectives; Descola, P., Pálsson, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. Dreaming of dragons: On the imagination of real life. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. (N.S.) 2013, 19, 734–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, R. Introduction. In Redefining nature. Ecology, Culture and Domestication; Ellen, R., Fukui, K., Eds.; BERG: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, A. The invention of nature. In The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, the Lost Hero of Science; John Murray: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and peoples: The social impact of protected areas. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, D.; Duffy, R.; Igoe, J. Nature Unbound, Conservation, Capitalism and the Future of Protected Areas; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Strathern, M. No nature, no culture: The Hagen case. In Nature, Culture and Gender; MacCormack, C., Strathern, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; pp. 174–222. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, S.; Pretty, J. Nature and culture: An introduction. In Nature and Culture; Pilgrim, S., Pretty, J., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, W. The trouble with wilderness; or, getting back to the wrong nature. In Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature; Cronon, W., Ed.; W. W. Norton; Co.: London, UK, 1996; pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, B.L.; Brown, P.J.; Peterson, G.L. Benefits of Leisure, State College; Venture Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, R.; Kistemann, T. Blue space geographies: Enabling health in place. Health Place 2015, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and human well-being. Ecosystems 2005, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. Is physical activity in natural environments better for mental health than physical activity in other environments? Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 92, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Brink, P.; Mutafoglu, K.; Schweitzer, J.P.; Kettunen, M.; Twigger-Ross, C.; Kuipers, Y.; Emonts, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Hujala, T.; Ojala, A. The Health and Social Benefits of Nature and Biodiversity protection, EXECUTIVE Summary. A Report of European Commission. (ENV.B.3/ETU/2014/0039); Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley, H.E.A.; Tinsley, D.J. A theory of attributes, benefits and causes of leisure experience. Leis. Sci. 1996, 1, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, B.L.; Bruns, D.H. Concepts and uses of benefits approach to leisure. In Leisure Studies: Prospects for the 21st Century State College; Jackson, E.L., Burton, T.L., Eds.; Venture Publishing: Champaign, IL, USA, 1999; pp. 349–369. [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi, M.; Endo, J.; Takayama, N.; Murase, N.; Nishiyama, N.; Saito, H.; Fujiwara, A. Impact of Viewing vs. Not Viewing a Real Forest on Physiological and Psychological Responses in the Same Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 10883–10901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Corraliza, J.A. Conciencia ecológica y bienestar en la infancia. In Efectos de la Relación con la Naturaleza; CCS: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Ojala, A.; Korpela, K.; Lanki, T. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: A field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.; Simons, R.; Losito, B. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Piff, P.K.; Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Keltner, D. An occasion for unselfing: Beautiful nature leads to prosociality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzman, P. The spiritual benefits of leisure. Leisure/Loisir 2009, 33, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Benefits of Nature Contact for Children. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, M.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Van Poppel, M.; Kemper, H.; Van Mechelen, W.; Maas, J. Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bell, S.; Graham, H.; Jarvis, S.; White, P. The importance of nature in mediating social and psychological benefits associated with visits to freshwater blue space. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schebella, M.F.; Weber, D.; Lindsey, K.; Daniels, C.B. For the Love of Nature: Exploring the Importance of Species Diversity and Micro-Variables Associated with Favorite Outdoor Places. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Harvey, D. Transcendent experience in forest environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallimer, M.; Irvine, K.N.; Skinner, A.M.; Davies, Z.G.; Rouquette, J.R.; Maltby, L.L.; Warren, P.H.; Armsworth, P.R.; Gaston, K.J. Gaston, Biodiversity and the Feel-Good Factor: Understanding Associations between Self-Reported Human Well-being and Species Richness. BioScience 2012, 62, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B.W.; Lovell, R.; Higgins, S.L.; White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Osborne, N.J. Beyond greenspace: An ecological study of population general health and indicators of natural environment type and quality. Int. J. Health Geographic’s 2015, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, S.; Have, M.; van Dorsselaer, S.; van Wezep, M.; Hermans, T.; de Graaf, R. Local availability of green and blue space and prevalence of common mental disorders in the Netherlands. Br. J. Psychiatry Open 2016, 2, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triguero-Mas, M.; Dadvand, P.; Cirach, M.; Martínez, D.; Medina, A.; Mompart, A. Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: Relationships and mechanisms. Environ. Int. 2015, 77, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. Place Attachment: A Conceptual Inquiry. Place Attach. 1992, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.; Devine-Wright, P. Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ried, A.; Le Bon, A.; Carmody, S.; Santos, R. Sentidos del lugar desde la experiencia de ocio y turismo en áreas silvestres protegidas: Una metasíntesis. PASOS. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2018, 16, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. Place Attachment; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer, B.; Krannich, R.; Blahna, D. Attachments to Special Places on Public Lands: An Analysis of Activities, Reason for Attachments, and Community Connections Society. Nat. Resour. Int. J. 2000, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Chick, G. The Social Construction of a Sense of Place. Leis. Sci. 2007, 29, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budruk, M.; Stanis, S.A.W. Place attachment and recreation experience preference: A further exploration of the relationship. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2013, 1–2, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campelo, A.; Aitken, R.; Thyne, M.; Gnoth, J. Sense of Place: The Importance for Destination Branding. J. Travel Res. 2013, 53, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynveen, C.J.; Kyle, G.T.; Absher, J.D.; Theodori, G.L. The Meanings Associated with Varying Degrees of Attachment to a Natural Landscape. J. Leis. Res. 2011, 43, 290–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokowski, P.A. Languages of place and discourses of power: Constructing new senses of place. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynveen, C.J.; Kyle, G.T.; Sutton, S.G. Place Meanings Ascribed to Marine Settings: The Case of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Leis. Sci. 2010, 32, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. The Social Construction of Tourist Places. Aust. Geogr. 1999, 30, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D.; Sowers, J. Place and Placelessness, Edward Relph. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y. Topofilia (1a); Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Space and Place (1977): Yi-Fu Tuan. In Key Texts in Human Geography; Hubbard, P., Kitchin, R., Valentine, G., Eds.; 2008; pp. 53–61. Available online: http://0-knowledge.sagepub.com.oasis.unisa.ac.za/view/key-texts-in-human-geography/SAGE.xml (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Davenport, M.; Anderson, D. Getting From Sense of Place to Place-Based Management: An Interpretive Investigation of Place Meanings and Perceptions of Landscape Change. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianicka, S.; Buchecker, M.; Hunziker, M.; Müller-Böker, U. Locals’ and Tourists’ Sense of Place. Mt. Res. Dev. 2006, 26, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.; Borodulin, K.; Neuvonen, M.; Paronen, O.; Tyrväinen, L. Analyzing the mediators between nature-based outdoor recreation and emotional well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.B. A Cross-Cultural Examination of Favorite Places. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggenbuck, J.W.; Driver, B.L. Benefits of non-facilitated uses of wilderness. Scientist 2000, 3, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising cultural ecosystem services: A novel framework for research and critical engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, N.; Munday, M.; Durance, I. The challenge of valuing ecosystem services that have no material benefits. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 44, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.A. Dimensions of Choice: Qualitative Approaches to Parks, Recreation, Tourism, Sport, and Leisure Research, 2nd ed.; Palo Alto: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, M.E.; Watson, A.E.; Williams, D.R.; Roggenbuck, J.R. An Hermeneutic Approach to Studying the Nature of Wilderness Experiences. J. Leis. Res. 1998, 30, 423–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H.W. Ecology of the heart: Understanding how people experience natural environments. Nat. Resour. Manag. Hum. Dimens. 1996, 13, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Amsden, B.L.; Stedman, R.C.; Kruger, L.E.; Anderson, D.H.; Fulton, D.C.; Approaches, G.; Theodori, G.L. The Meanings Associated with Varying Degrees of Attachment to a Natural Landscape. Leis. Sci. 2013, 28, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Williams, D. Collecting and Analyzing Qualitative Data: Hermeneutic Principles, Methods, and Case Examples; Venture: Champaign, IL, USA, 2002; pp. 1–129. [Google Scholar]

- Champ, J.G.; Williams, D.R.; Knotek, K. Wildland Fire and Organic Discourse: Negotiating Place and Leisure Identity in a Changing Wildland Urban Interface. Leis. Sci. 2009, 31, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The discovery of grounded theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods 1967, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introducción a los Métodos Cualitativos; Paidos, Ed.; 2000; Available online: https://asodea.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/taylor-s-j-bogdan-r-metodologia-cualitativa.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Matless, D. Moral geography in Broadland. Ecumene 1994, 1, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S. Theorizing Outdoor Recreation and Ecology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ried, A.; Monteagudo, M.J.; Benavides, P.; Le Bon, A.; Carmody, S.; Santos, R. Key Aspects of Leisure Experiences in Protected Wilderness Areas: Notions of Nature, Senses of Place and Perceived Benefits. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083211

Ried A, Monteagudo MJ, Benavides P, Le Bon A, Carmody S, Santos R. Key Aspects of Leisure Experiences in Protected Wilderness Areas: Notions of Nature, Senses of Place and Perceived Benefits. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083211

Chicago/Turabian StyleRied, Andrés, María Jesús Monteagudo, Pelayo Benavides, Anne Le Bon, Stephanie Carmody, and Rodrigo Santos. 2020. "Key Aspects of Leisure Experiences in Protected Wilderness Areas: Notions of Nature, Senses of Place and Perceived Benefits" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083211

APA StyleRied, A., Monteagudo, M. J., Benavides, P., Le Bon, A., Carmody, S., & Santos, R. (2020). Key Aspects of Leisure Experiences in Protected Wilderness Areas: Notions of Nature, Senses of Place and Perceived Benefits. Sustainability, 12(8), 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083211