Does Board Gender Diversity Bring Better Financial and Governance Performances? An Empirical Investigation of Cases in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Female Directors and Firms’ Financial Performance

2.2. Female Directors and Corporate Governance

3. Materials and Methods

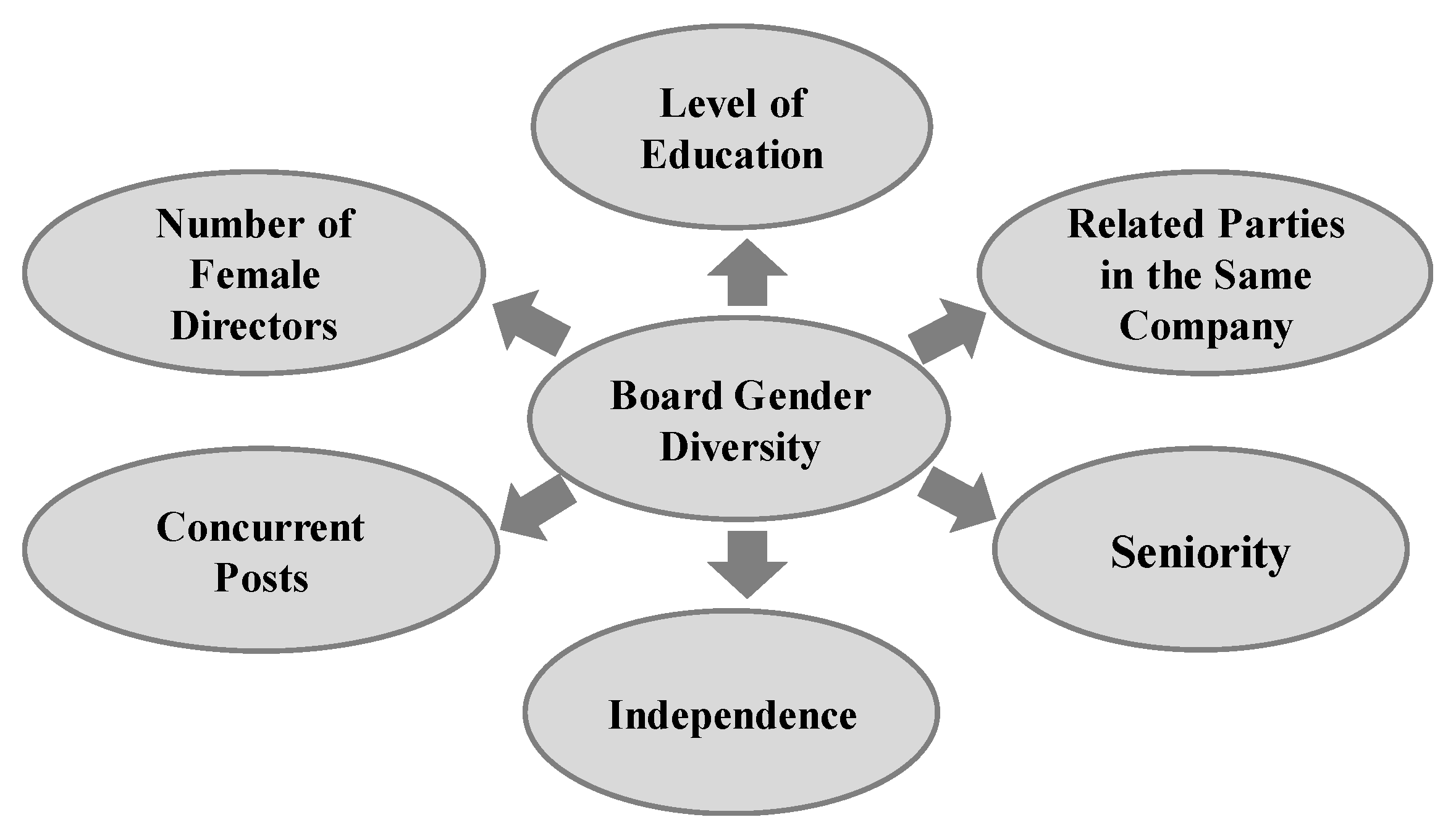

3.1. Main Explanatory Variable—Gender Diversity

3.2. Interpreted Variable—Performance

3.3. Measurement Model

- The relationship between board gender diversity and the firm’s Tobin’s Q:Tobin’s Q = β0 + β1 FMBNUM + β2 FMBEDU + β3 FMBSNY+ β4

FMBNET + β5 FMBIND + β6 FMBCUR + e - The relationship between board gender diversity and the firm’s ROA:ROA = β0 + β1 FMBNUM + β2 FMBEDU + β3 FMBSNY+ β4

FMBNET + β5 FMBIND + β6 FMBCUR + e

3.4. Data and Sample

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

4.2. Effects of Board Gender Diversity on a Firm’s Governance and Performance

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.-H. The Impact of Gender Diversity of Corporate Boards on Corporate Governance: An Empirical Investigation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Management and Information Technology (ICMIT), Auckland, UK, 16–17 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Annette, E. Quotas Get More Women on Boards and Stir Change from Within Horizon: The EU Research & Innovation Magazine. 2018. Available online: https://horizon-magazine.eu/article/quotas-get-more-women-boards-and-stir-change-within.html (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Nielsen, S.; Huse, M. Women directors and board strategic decision making: The moderating role of equality perception. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 7, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Salloum, C.C.; Azoury, N.M.; Azzi, T.M. Board of directors’ effects on financial distress evidence of family owned businesses in Lebanon. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2013, 9, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.; Jamali, D. Looking inside the black box: The effect of corporate governance on corporate social responsibility. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2016, 24, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C. Board composition and corporate social responsibility: The role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, K.; Post, C. Women on boards of directors and corporate social performance: A meta-analysis. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2016, 5, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranchuk, N.; Dybvig, P.H. Consensus in Diverse Corporate Boards. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 715–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lückerath-Rovers, M. Women on boards and firm performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2013, 17, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, A.A.; Ntim, C.G.; Al-Najjar, B. Board diversity, corporate governance, corporate performance and executive pay. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 24, 761–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, N.L.; Werbel, J.D.; Shrader, C.B. Board of director diversity and firm financial performance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2003, 11, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A.; Northcraft, G.B.; Neale, M.A. Why Differences Make a Difference: A Field Study of Diversity, Conflict, and Performance in Workgroups. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.D.; Milton, L.P. How Experience and Network Ties Affect the Influence of Demographic Minorities on Corporate Boards. Adm. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 366–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.M.; Kramer, V.W. How many women doboards need? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hafsi, T.; Turgut, G. Boardroom Diversity and its Effect on Social Performance: Conceptualization and Empirical Evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, R.A.; Bosco, S.M.; Vassill, K.M. Does female representation of boards of directors associate with Fortune’s “100 best companies to work for” list? Bus. Soc. 2006, 45, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, R.A.; Guptill, S.T. Social desirability response bias, gender and factors influencing organizational commitment: An international study. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; Mattis, M.C. Women on Corporate Boards of Directors: International Challenges and Opportunities; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, C.M.; Certo, S.T.; Dalton, D.R. A decade of corporate women: Some progress in the boardroom, none in the executive suite. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Vinnicombe, S. Why So Few Women Directors in Top UK Boards? Evidence and Theoretical Explanations. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2004, 12, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Sphropshire, C.; Cannella, A.A. Organizational Predictors of Women on Corporate Boards. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huse, M.; Solberg, A.G. Gender related boardroom dynamics: How women make and can make contributions on corporate boards. Women Manag. Rev. 2006, 21, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Nicolas, C.M.; Martín-Ugedo, J.F.; Mínguez-Vera, A. The influence of gender on financial decisions: Evidence from small start-up firms in Spain. E+M Ekon. Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, P.B.; Lam, K.C.K.; Vieito, J.P. Gender and other major board characteristics in China: Explaining corporate dividend policy and governance. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.A.; D’Souza, F.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. The Gender and Ethnic Diversity of US Boards and Board Committees and Firm Financial Performance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2010, 18, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Xie, F. Do women directors improve firm performance in China? J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 28, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalyst. The Bottom Line. Connecting Corporate Performance and Gender Diversity; Catalyst: 2004. Available online: https://www.catalyst.org/research/the-bottom-line-connecting-corporate-performance-and-gender-diversity/ (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Campbell, K.; Mínguez-Vera, A. Gender Diversity in the Boardroom and Firm Financial Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Credit Suisse. Women on Boards. Gender Diversity and Corporate Performance; Credit Suisse: Zürich, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.B.; Ferreira, D. Women in the Boardroom and Their Impact on Governance and Performance. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 94, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, C. Does female board representation influence firm performance? Dan. Evid. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2007, 15, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, K.; Hersch, P. Additions to corporate boards: The effect of gender. J. Corp. Financ. 2005, 11, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadbury, S.A. The corporate governance agenda. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2000, 8, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Z.; Kouser, R.; Ali, W.; Ahmad, Z.; Salman, T. Does Corporate Governance Affect Sustainability Disclosure? A Mixed Methods Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.A.; Angelidis, J.P. Effect of board members’ gender on corporate social responsiveness orientation. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 1994, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Bel-Oms, I.; Olcina-Sempere, G. Is Board Gender Diversity a Driver of CEO Compensation? Examining the Leadership Style of Institutional Women Directors. Asian Women 2017, 33, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harakeh, M.; El-Gammal, W.; Matar, G. Female directors, earnings management, and CEO incentive compensation: UK evidence. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 50, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Zaman, R.; Saleem, I. Boardroom gender diversity and corporate sustainability practices: Evidence from Australian Securities Exchange listed firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, S.; Sealy, R.; Singh, V. Women Directors on Corporate Boards: A Review and Research Agenda. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2009, 17, 320–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondas, N.; Sassalos, S. A different voice in the boardroom: How the presence of women directors affects board influence over management. Glob. Focus 2000, 12, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Demsetz, H.; Villalonga, B. Ownership structure and corporate performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2001, 7, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TWSE. 2020. Available online: https://cgc.twse.com.tw/frontEN/evaluationOverview (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Armstrong, B.G.; Sloan, M. Ordinal regression models for epidemiological data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989, 129, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłoński, A.; Jabłoński, M. Business & Economics; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; p. 366. [Google Scholar]

| Companies’ TCGI Relative Rank | TCGI Rank | Codes Used in Model |

|---|---|---|

| Top 5% | A+ | 7 |

| 6–20% | A | 6 |

| 21–35% | B | 5 |

| 36–50% | C | 4 |

| 51–65% | C- | 3 |

| 66–80% | D | 2 |

| 81–100% | D- | 1 |

| Unsuitable or data unavailable | NA | - |

| Variable | Means | Standard Deviation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FMBNUM | 0.9315 | 1.013 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | FMBEDU | 0.0506 | 0.08681 | 0.573 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3 | FMBSNY | 7.3429 | 8.90 | 0.490 ** | 0.193 ** | 1 | |||

| 4 | FMBNET | 0.3942 | 0.58911 | 0.598 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.569 ** | 1 | ||

| 5 | FMBIND | 0.0306 | 0.06781 | 0.490 ** | 0.510 ** | 0.037 | 0.017 | 1 | |

| 6 | FMBCUR | 2.8822 | 4.2084 | 0.402 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.389 ** | 0.345 ** | 0.176 ** | 1 |

| Regression | Multiple Regression | Ordinal Regression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Tobin’s Q | ROA | TCGI |

| Coefficient (p-Value) | Estimate (p-Value) | ||

| FMBNUM | 0.39 (0.265) | −0.006 (0.863) | 0.132 (0.168) |

| FMBEDU | 0.007 (0.841) | −0.037 (0.304) | −0.904 (0.297) |

| FMBSNY | −0.43 (0.157) | −0.041 (0.177) | −0.018 * (0.027) |

| FMBNET | 0.03 (0.330) | −0.025 (0.412) | −0.165 (0.236) |

| FMBIND | 0.065 * (0.033) | 0.072 * (0.019) | 0.623 (0.57) |

| FMBCUR | 0.017 (0.596) | −0.014 (0.65) | 0.093 *** (0.000) |

| Intercept | 1.113 *** (0.000) | 7.993 *** (0.000) | - |

| Adjusted R² | 0.003 | 0.004 | - |

| Pseudo R-Square | - | - | Cox & Snell 0.042 Nagelkerke 0.043 McFadden 0.011 |

| F_Value | 4.546 * | 5.549 * | - |

| χ² (df) | - | - | 41.246 (6 df) *** |

| Test of Parallel Lines | - | - | 0.297 |

| # of obs. | 1065 | 1063 | 964 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.-H. Does Board Gender Diversity Bring Better Financial and Governance Performances? An Empirical Investigation of Cases in Taiwan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083205

Wang Y-H. Does Board Gender Diversity Bring Better Financial and Governance Performances? An Empirical Investigation of Cases in Taiwan. Sustainability. 2020; 12(8):3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083205

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yu-Hui. 2020. "Does Board Gender Diversity Bring Better Financial and Governance Performances? An Empirical Investigation of Cases in Taiwan" Sustainability 12, no. 8: 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083205

APA StyleWang, Y.-H. (2020). Does Board Gender Diversity Bring Better Financial and Governance Performances? An Empirical Investigation of Cases in Taiwan. Sustainability, 12(8), 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083205