1. Introduction

The gender gap in political knowledge is a classical problem of Western democracies. Extensive research has documented sizeable and persistent gender differences in political knowledge, finding that men tend to be more politically knowledgeable than women. Historically, the focus has been on the analysis of sociological variables [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. In recent years, research has revolved around the way in which such knowledge is measured, the formulation of the questions and the topics introduced; in other words, the methodology of the surveys [

8,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The role of context [

14,

16,

17] and the relationship of the gap with theories of risk aversion [

18] has also been a matter of study. In this paper, we aim to explore the subject from another perspective: the modernization of Spain.

“Modernization brings systematic, ‘predictable’ changes in gender roles” [

19]. This paper therefore fits in with recent literature that seeks to study whether differences in political interest by gender change over time [

20,

21,

22].

The changes that took place in Spain after the death of the dictator General Francisco Franco in 1975—its transformation into a democracy with a market economy and its inclusion in 1986 as a member state of the European Union—opened the doors of the political system to women. This scenario leads to formulate the following hypothesis: ‘The gender gap in political knowledge is reduced as progress is made on the road towards equality between men and women. This happens with the support of the State through the public policies it implements, not just as a consequence of an increase in individual resources (mainly, education and employment) of the female population’. A normative and political framework that defends gender equality changes cultural attitudes, driving women‘s access to political knowledge and diminishing the gender gap, one of the first steps to go towards a sustainable society in all its dimensions—economic, political and social. The issue, therefore, is to understand how women’s political knowledge has evolved over time.

Sociological panel or longitudinal studies are uncommon in Spain and rarely cover long periods of time, in terms of years. Likewise, it is difficult to find specific opinion surveys that are carried out regularly and are comparable over time. Fortunately, the monthly barometers of the Centre for Sociological Research (CIS) have maintained regular questions related to the political field, one of which will help us in the process of finding answers to the question and hypothesis raised in this paper. Specifically, we use the microdata of the 242 monthly CIS barometers from 1996 to 2017 to reinforce or reject our hypothesis.

The adoption of the methodological approach to modernization and gender equality of Inglehart and Norris [

19,

23] involves combining the sociological perspective with the political perspective. The modernization process in Spain includes the development of a public education system, the incorporation of women into the labour market and the construction of the welfare state in a legislative framework that respects fundamental rights and freedoms. Therefore, this paper considers sociological variables as well as public policies and laws adopted by the government to influence women’s access to political knowledge. These variables modulate classical gender roles and encourage female access to political knowledge, as Fraile and Gomez point out in their study of Latin America [

24].

The role of the State refers to the ability of the government to change the legal, political and social system through public policies, laws or even the reform of the Constitution. A distinction should be drawn between the direct and indirect effects of the State. In the former, the action of the State concerns public policies aimed at increasing resources associated with political knowledge: education, income and employment [

5]. Labour policies can encourage women to work outside the home, education policies can open state universities to women, increasing their level of education, and social policies can reduce the time women invest in care at home by offering care through social services. These three variables may explain the higher level of political knowledge of women at the same time that a reduction in the political knowledge gender gap is seen. In the latter case, that of indirect effects, the focus is on the ability of the State to change political behaviour through the progressive implementation of its policies. As we will see, after controlling for levels of education and/or socio-economic status, the gap in political knowledge between men and women is further reduced as a by-product of the modernization process.

Political knowledge is a fundamental tool for the full political participation of citizens, reinforcing democracy. Conversely, lacking cognitive skills such as the ability to analyse is an obstacle to understanding the complexity of the political system [

5]. As [

25] points out, less political knowledge leads to less interest in politics, which results in less political participation and less sustainable societies. If this phenomenon characterizes women as a group in a constant way, it would mean that women’s political representation would be diminished as well as the defence of their interests. This would negatively affect the functioning of democracy because not all citizens would participate on equal terms. There would be first-class citizens and second-class citizens, in this case women who are left behind. Any intention of building an inclusive and sustainable society requires the introduction of gender perspective starting from equal gender access to political knowledge. According to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number five, in particular target 5.5, ensuring women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities at all levels of decision–making in political, economic and public life is a key element for empowering all women and girls [

26]. SDG incorporates the social dimension into the concept of sustainable development [

27], placing gender equality as a central objective with cross-cutting effects. Sustainable development cannot be achieved without women.

Since the end of the nineties, with Spain continuing to develop as a modern country, both democratically and economically, what has been the evolution of the gender gap in political knowledge? Has inequality remained unchanged in this field? The longitudinal analysis of the opinion surveys of the CIS and the crossing with the variables of level of education and occupation may provide the evidence necessary to answer these questions. The study of the legislative changes in the matter of equality between men and women, as well as the public policies implemented, will highlight the role assumed by the State.

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, the role of the state in the process of modernization of Spain towards a gender inclusive sustainable society is discussed. The contribution of the state in reducing the gender gap in political knowledge is addressed from two perspectives, laws and public policies and the construction and consolidation of the contemporary Spanish welfare state. In the third section, the data and the variables used, as well as their limitations, are described. The fourth section is devoted to the analysis of the sociological change observed, through the variables level of education and occupation and also after controlling for them. Finally, the conclusions are presented.

2. The Role of the State: Driving Force for Change

After the death of General Francisco Franco, the dictator who governed for almost four decades (1939–1975), Spain began a path of modernization with the establishment of a social and democratic state of law in an open economy, modifying the institutional and political framework. Firstly, the Francoist regime of national-Catholic nature was replaced by a liberal democracy. The Spanish Constitution (SC) of 1978 introduced a new legal framework that must be governed by equality between men and women, as set out in articles 1.1 and 14. Secondly, as the democratic and social State was consolidated, a series of laws and public policies were approved to establish the principle of equality without gender discrimination (art. 9.2 SC). Thirdly, the welfare state was built, transferring resources and services from the family to the State while creating jobs in feminized sectors such as care and education [

28].

This section outlines the role of the State in the elimination of the formal and real gender gap, one of the explanatory factors for the path towards equality between men and women, according to [

19]. First, the main laws adopted by the government to guarantee equality between men and women are reviewed. Second, the construction of the welfare state in democratic Spain and its effects on women are addressed, facilitating their incorporation into the education system as well as the labour market through the political action of the government. These two processes provide the female population with basic resources to increase their level of political knowledge—cognitive skills and money [

25]—which in turn directly affect the socialization process and thus modify their patterns of political behaviour and make them more interested in politics [

29]. It is a way of reaching those people, specifically women, who had been previously excluded from developing their role because of the implementation of policies and laws with a gender-biased approach [

30].

2.1. Laws and Public Policies

With the arrival of democracy, Spain began to develop the principle of equality between men and women within the new legislative framework. With a sequence of laws and public policies, whose main milestones are presented below, the State took an active role in the construction of an egalitarian society. Of special relevance are the laws of 1981 that reformed the Civil Code in relation to marriage. Law 11/1981 places the woman in legal equality with her husband in the administration and disposition of the matrimonial assets. For example, prior to this, a man could cite his wife’s infidelity as a cause of separation but a woman could not.

The approval in 1983 of the Women’s Institute of Spain (WI) was aimed at eliminating the obstacles that prevent effective equality between men and women. It introduced state feminism similar to other European countries, albeit ten years later due to the presence of a dictatorship in Spain, until the mid-seventies. The WI is responsible for coordinating and promoting public equality policies and has continued to develop in the different Spanish regions (autonomies) in line with the autonomic territorial organization of the State [

31]. Law 9/1985 followed the same objective with the approval of the decriminalization of abortion, broadening the possibilities for women to decide for themselves about motherhood.

Spain joining the European Union in 1986 was a turning point. In fact, the EU becomes a key factor for understanding how the modernization process of Spain moves towards a gender inclusive sustainable society. The legislative framework has to be reformed to introduce European parameters in terms of gender equality. The nineties were characterized by the transposition of important European directives in this regard: the Europeanization of Spain [

32,

33,

34].

This European influence can be seen in the I Plan for Equality of Opportunities for Men and Women in Spain (PEOW), which dates back to 1988 and aimed to improve the social situation of women. The measures covered six different areas, from equality in the legal system to family and social protection, education and culture, employment and labour relations, health, and international cooperation and associationalism. The II PEOW (1993–1995) set out that positive action measures be a priority to undertake structural changes in order to achieve real equality. In this case, the actions were mainly focused on three areas: education, training and employment. The III PEOW (1997–2000) pursued the co-participation of women in society as a whole. To this end, Spain introduced the principle of equality in all public policies in accordance with the Fourth World Conference of Women in Beijing and the IV EU Program of Community Action. Once again, both the European and International framework play their part in the design of Spanish public policies [

35]. The subsequent Plan (2001–2005) was based on the guidelines of the Community Framework Strategy on Equality between Men and Women. It introduced the principle of gender mainstreaming, and it also required the implementation of specific equal opportunity policies.

However, inequality based on gender continues to be deep-rooted, despite the legislative changes and the public policies adopted. Its most cruel manifestation is gender violence. Thus, in 2004, the Organic Law 1/2004 on Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence was approved. However, significant gaps remain. In 2007, the sanction of the Equality Act 3/2007 for the Effective Equality of Men and Women represented a leap forward. It introduced the principle of gender mainstreaming, which requires that laws, public policies and any political action must incorporate the objective of equality as a fundamental principle. It addresses the problem of inequality from an integral perspective that goes beyond the formal dimension. One new approach is based on the forecast of active policies to meet the objectives of the law. As its title indicates, the ultimate goal is effective equality, conceiving the principle of equality as a transversal principle that affects the set of public policies and actions implemented by public authorities. Law 3/2007 involves the adoption or modification of other laws. Such is the case of the Electoral Law, in which Article 44 is modified to introduce the principle of gender-balanced representation to achieve gender parity in candidacies.

Another basic law on gender equality is Law 39/2006 on the Promotion of Personal Autonomy and Care for people in situations of dependency. The so-called Dependency Law aims to establish a care system for individuals without personal autonomy, externalizing the care functions that the patriarchal system assigns to women as "household obligations". However, the lack of political will and resources, especially with the onset of the global financial crisis in 2009, meant a downswing in its implementation. For example, the approval of a wage equality law to eliminate the gender wage gap is pending. Similarly, the presence of women on the Board of Directors of companies was barely 15% in 2016 [

36]. This law addresses neither the unresolved problem of gender violence nor the conciliation of work and family life for a working mother.

The 2008-2011 PEOW is structured around the Law of Equality, emphasizing the empowerment of women, gender mainstreaming or the redefinition of the concept of citizenship so that women are not excluded. The following Equality Plan (2014-2016) continues adopting the dual approach that combines specific equality policies with mainstreaming for structural changes.

All these laws and policies, despite their limitations, pave the way for the incorporation of women into the public sphere, forming part of the process of modernization of Spain, promoting the empowerment of women, recognizing their rights and facilitating access to the labour market, for example, through maternity leave. In addition, they imply the incorporation of the problem of gender inequality in the political agenda, highlighting the gender gap. This new normative and political framework is inseparable from the social transformation of women in Spain at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century as will be seen later. These structural changes help women gain a greater knowledge of the political sphere, by breaking free of the limitations of the home environment and playing a bigger part in the public sphere. When working outside the home—even if in the domestic sphere of other homes—there is the possibility of interacting with other actors beyond the members of the family unit, making social connections and receiving remuneration, having new life experiences (lifelong learning) and developing other skills [

37].

2.2. The Welfare State

The process of modernization of Spain cannot be understood without considering the construction of the welfare state. The incorporation of the social dimension into the concept of citizenship modifies relations between the State, the market and the family, with a direct impact on women [

38]. The development of a universal social protection system involves the outsourcing of a part of the caretaker function that a patriarchal system assigns to women rather than men. The welfare regime promotes the liberalization of women by redistributing the classic feminine tasks (

caregiver) between the State, the market and the family [

39]. The pension system, for example, allows some economic autonomy for retired people, increasing the social fabric and reducing the care function traditionally assigned to women in the family. This change links to the incorporation of women into the labour market and the redefinition of their role in the family and the workplace, which erodes the traditional family model of the male as sole breadwinner.

However, the democratic welfare state in Spain has been built

“conditioned by [...] its specific historical path or path dependency (centrality of Social Security, the importance of the sphere of family support and a third social development action plan)” [

40]. The family —in particular, women— is perceived as a fundamental axis, the same way as other member countries of the so-called Mediterranean welfare regime [

41]. The State builds a social protection network, where the family and, in particular, women are the main providers of care [

42].

The first step towards the current welfare regime occurs with the adoption of the Moncloa Pacts in 1978. It establishes a universal pension system, which is the flagship policy of the Spanish welfare state. The universalization of the public health system is achieved with the General Health Law of 1986, becoming the second pillar of the welfare state. A few years later, the reform of the educational system established the foundations of universal education. The extension of social protection in these areas is a milestone in itself. On the one hand, it reduces the domestic responsibilities traditionally assumed by women thereby increasing their disposable time. On the other hand, it promotes the level of education of women by opening the doors to secondary and higher education. If we add to this the massive entry of women into the labour market [

43], it is clear that this new form of social and economic organization favours female participation in the public sphere. However, the provision of services for children and the elderly is not channelled through the State but is located in the private sphere, the family, as in the rest of the Mediterranean countries outside the framework of public administration [

44].

At the beginning of the 21st century, the Spanish government reformed its family welfare system, planning to free women from their domestic obligations. Such is the case of the Law of Dependency of 2006 (LO 39/2006) that aims to create a system of care for individuals without personal autonomy. Other measures include, for example, the universalization of pre-school education [

45]. The welfare state, as an explanatory factor of the liberalization of women in Spain, acts by providing social welfare at the same time as creating employment, although its process of implementation comes with limitations, as it is explained later regarding the labour market.

The onset of the global financial crisis in 2009, however, paralized the reform and expansion of the Spanish welfare state. The result is, for example, that Spain continues to rely on women as carers [

46]. Since 2009, because of the financial crisis, the implementation of a restrictive economic policy of public spending with large cuts in social services has shaken the existing social protection system that had facilitated women’s access to the public sphere. As a result, the role of the welfare state as the driving force for the liberalization of women and, in particular, the reduction of the gender gap in political knowledge is diminished. Given this scenario, the family resurfaces as a provider of well-being, bringing with it

“a certain refeminization of personal care” [

40] motivated by the obligation of family solidarity. This represents a retrograde step on the path towards a sustainable society in economic, social and political terms.

3. Data and Selected Variables

Having described the role of the State in the emancipation of women in Spain, we turn to the analysis of the data and the variables used to assess our hypothesis. The issue is to understand how women’s political knowledge has evolved during this period. Surveys appear to be an appropriate instrument for collecting this information. Sociological longitudinal studies are uncommon in Spain and rarely cover long periods of time, in terms of years. Likewise, it is difficult to find specific opinion surveys that are carried out regularly and are comparable over time. Fortunately, the monthly barometers of the CIS have maintained regular questions related to the political field, one of which will help us in the process of finding answers to the questions and hypotheses raised in this research. The 242 monthly barometers analysed in this document cover the period 1996–2017.

The CIS surveys are a reference in the Spanish public opinion sector [

47], and they provide an adequate representation of the universe (Spaniards over 18 years of age) with respect to other variables of interest (education, occupation) that we consider in our study [

48,

49]. The CIS barometers are personal surveys conducted in homes, with a sample size of 2500 individuals. CIS chooses households through a complex sampling procedure in which stratified sampling, cluster sampling, random routes and age and gender quotas are applied. This guarantees national representativeness of CIS surveys. CIS barometers are conducted monthly (except in August). Each month, the survey is devoted to a specific topic, which varies from one survey to another, although they can be revisited from time to time. In addition to the thematic blocks, the survey maintains some permanent blocks and repeated questions, which enables their analysis over time.

The thematic block of interest for this study is the block A.3, Political Culture, which contains the question “And referring now to the general political situation in Spain, how would you rate it: very good, good, fair, bad or very bad?”. This question has been asked repeatedly throughout the period under study. We use this question as reference to measure the political knowledge of respondents. Specifically, if an individual answers ‘Do not know’, we will assume that s/he has no knowledge about politics. The question includes among its response options also the ‘No Answer’ option. The percentage of respondents who chose this alternative is, so small that it has not been considered.

Obviously, although there are many reasons not related to the level of political knowledge for a person to choose ‘Do not know’ (among them, to hide an actual opinion, or because they do not care enough to answer or because they are bored with the survey), in our view, this limitation does not invalidate our analysis. On the one hand, the wording of the question (which is direct, simple and quite general) has remained unchanged over the years, meaning the respondents are always faced with the same question. On the other hand, we have no reasons to believe that as the years go by women are less likely to choose the option ‘Do not know’ for reasons not related to political knowledge. Hence, as our study simply sets out to review whether the gender gap has been reduced over the years even after controlling for education level and occupation status, we consider that, despite this potential limitation of the data, the answers to this question can properly capture the trends of political knowledge by gender.

The limitations of the data not only refer to the different meanings/motivations of these

‘Do not know’ answers, but also are related to whether they may really capture in full people’s political knowledge. The concept of political knowledge is broad: it has many dimensions and no single question can measure it in full [

16]. Indeed, according to [

4] it comprises elements related to the institutions and processes of the political system, its leaders and players, and about issues linked to domestic and foreign politics and policies. Unfortunately, in Spain a longitudinal dataset containing such a detailed information is not available, not even a homogeneous corpus of cross-sectional datasets collecting information about these topics, so our measure provides a simple, synthetic indicator to measure political knowledge over the years.

In addition to the above variable, other sociological variables of interest repeatedly observed in CIS barometers include

level of education (studies) and

socio-economic status (occupation), two individual level variables repeatedly found in the literature as relevant predictors of political knowledge and also two main goals of a sustainable society—number 4 and number 8, respectively—according to [

30]. We take advantage of these variables to conditionally study the temporal evolution of political knowledge by gender in order to analyse the indirect effects of the modernization process.

Regarding the level of education, CIS first asks if the individual has gone to school or has studied some type of course and, if so, what the highest official level of studies is that s/he has undertaken (regardless of whether the studies were finished or not). Based on these two questions we develop a variable called studies which has been homogenized, due to the different criteria followed by CIS during the more than two decades of barometers analysed, into the following groups:

Without studies: no studies or studies of less than 5 years of schooling.

Primary and lower secondary education: primary education not finished; primary and secondary education; primary vocational training and technical-vocational training or similar.

Upper secondary education: upper secondary education and intermediate level vocational training.

Higher studies: secondary vocational training or similar upper level vocational training and university studies.

After discarding surveys in which the answer about level of studies is: do not know, do not answer, others or simply the field is left blank, the total number of respondents who provided information about their studies in the period analysed is 597,067.

The socio-economic status of an individual is another of the variables identified in the literature as predictor. Such a variable can be approximated using the variable occupation. This is collected in detail in the CIS barometers and enables us to distinguish traditionally feminine and masculine work typologies. Throughout this paper, the CIS considers specific categories that enable important differences to be highlighted between the occupations of men and women.

In each barometer, each interviewee is first asked about their employment situation and whether s/he is: currently working; a student; retired or pensioner (previously worked); unemployed and seeking a first job; unemployed but worked before; a pensioner (previously did not work), in another situation; or carrying out unpaid domestic work. Then, if the interviewee is or has been in paid work, the next question is:

What is the current / was the last occupation or trade? In other words, what does the job entail? This double question enables us to identify if the individual works and, where appropriate, determine her/his occupation. Military occupations have been ruled out. Among the respondents who are outside the labour market, we have highlighted the group who declare themselves as belonging to the item of unpaid domestic work, given their relevance. Thus, this last group, together with those who have a paid occupation, represent a total of 237,162 occupations of the corresponding respondents. The items of this variable are shown in

Section 4.2.

4. Political Knowledge and Sociological Change

During the 1980s and 1990s, Spain underwent a huge sociological change. After 40 years of a Catholic dictatorship under Franco, a process of modernization began that encompassed the social sphere. The consolidation of a democratic and social state with a capitalist economy, membership in the European Union, and the construction of a welfare state are milestones, which transformed the role of Spanish women. A move was thus made from the patriarchal concept of the role of the woman as wife-mother confined to the home to the concept of a modern woman who works, studies at university and consigns motherhood to second place. The fertility rate dropped from 2.8 in 1976 to 1.33 in 2016 and the average age of women to motherhood rose from 28.5 to 32.0 years, in that same period [

50]. The country developed from an agrarian economy with an incipient industry to a services economy with a strong tourism industry. This has important consequences of a sociological and politico-juridical nature in the field of gender equality, as shown by the works of Inglehart and Norris [

19,

51] as well as the Global SDG Indicators Database [

52].

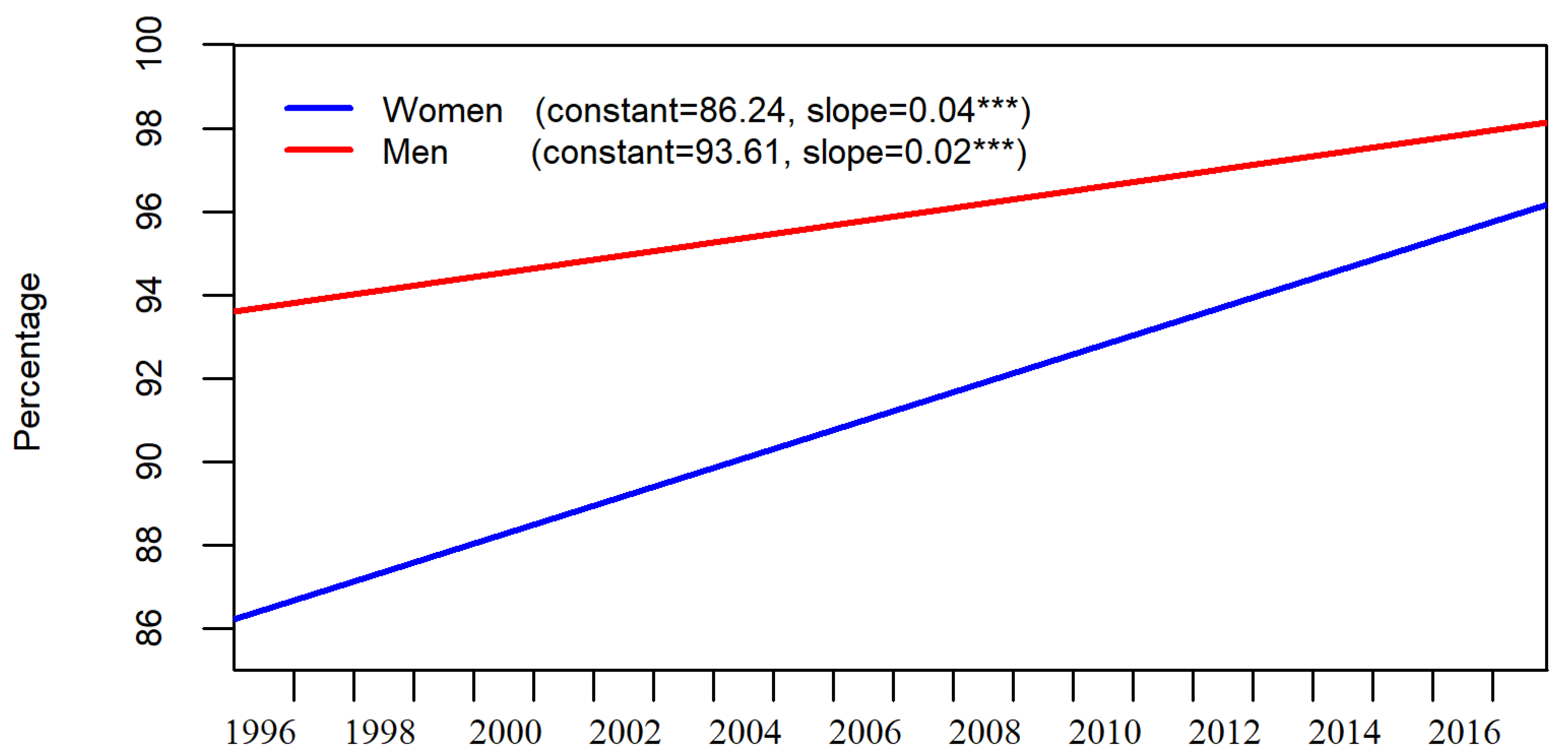

In what follows, we analyse gender gap in political knowledge attending to and also after controlling for two of the fundamental sociological variables that affect it: level of education and socio-economic status. The starting outcome is that the higher the level of education and the higher the socio-economic status of women, the less inequality in political knowledge between men and women. The sociological change resulting from modernization partly explains the decreasing trend of this gender gap, as

Figure 1 shows aggregated. The subsequent outcome is that the gap in political knowledge between men and women is further reduced as a by-product of the modernization process. The reduction that we observe in the gender gap in political knowledge after controlling for levels of education and/or socio-economic status reinforce this effect of modernization.

Figure 1 presents an overview of the evolution of gender gap in political knowledge in Spain. We have experienced a convergence in the levels of political knowledge of both sexes, without doubt (in part) as a consequence of the cumulative increases in levels of education and occupation of the female population (see

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2).

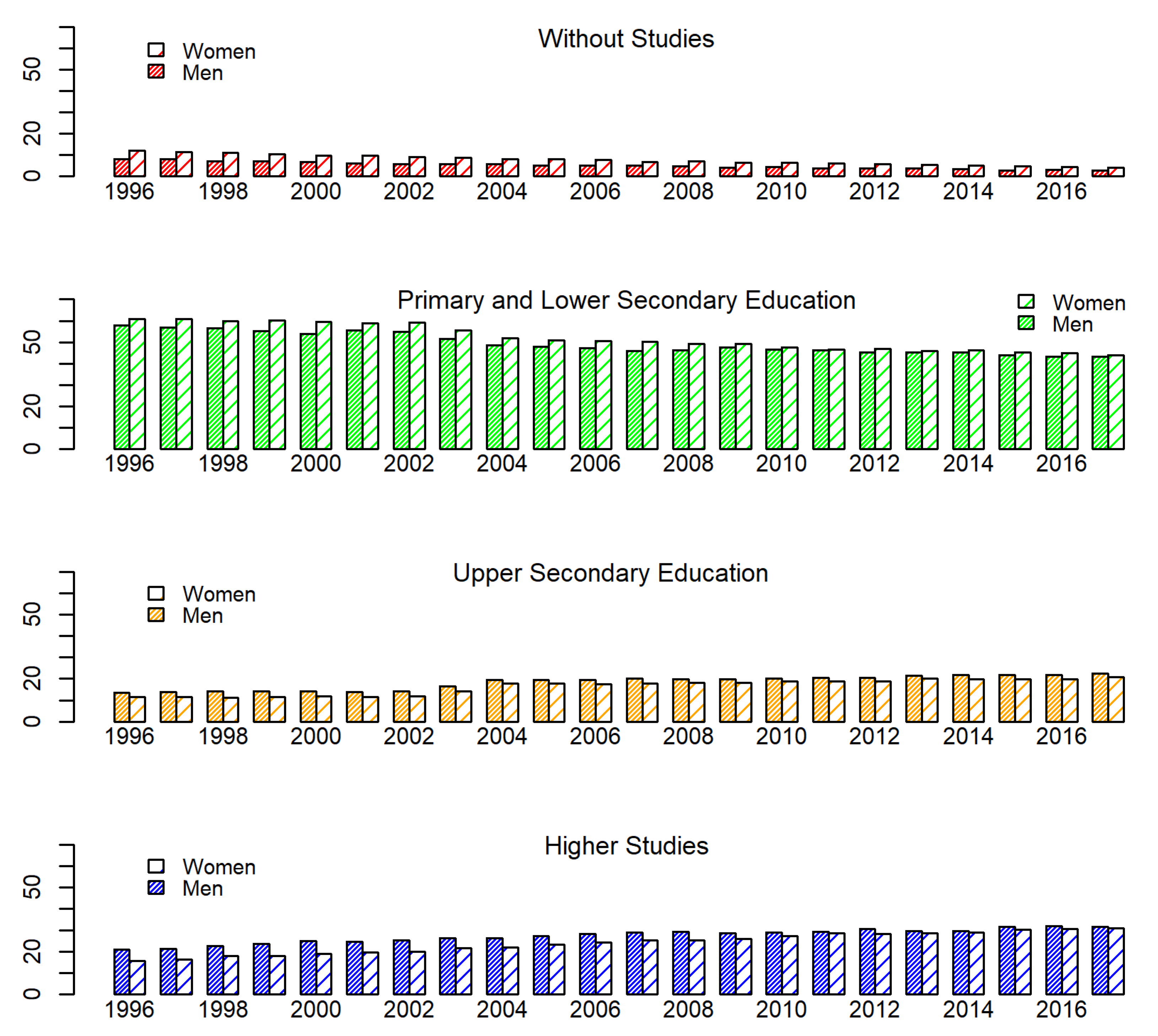

4.1. Education

The analysis of the percentage distributions by level of education of men and women (

Figure 2) leads us to conclude that the greatest presence in both genders is of people with primary and lower secondary education, followed by people with higher education. Upper secondary education occupies third place and, finally, people without studies represent a very small proportion of the total spectrum, albeit reducing over time.

In a comparison of studies by gender, we observe that although women still represent a higher proportion in the category without studies, they are closing the gap. In primary and lower secondary education, the percentage of women is higher than that of men, the gap nevertheless almost disappears at the end of the period. Regarding upper secondary education, men maintain their presence over that of women. Men started with a greater presence in higher studies than women but, latterly, women’s representation at this level has been growing, reaching the percentage level of that of men with higher studies. In short, the gaps have been reduced at all levels of education.

Education equips people with cognitive skills such as the ability to analyse and communicate, increasing their knowledge of the political system. Education is a source of intangible resources. It provides the person with the ability to read, collect and process information, communicate and, in short, understand the dynamics of the political game [

53,

54,

55]. The causal relationship between education and political participation has already been demonstrated in the work of Almond and Verba [

1], who showed that the most educated have the most resources to participate in politics.

As UNESCO itself proclaims, education is a tool for the empowerment of women. It opens the door to the public sphere, expanding the delimited space of the private sphere and the confines of the family. It breaks with the traditional division of gender that assigns men the role of breadwinners (paid work outside the home) and women the role of housekeepers, who deal with education and care of children and home (unpaid work). Women move in other environments beyond the home, gaining knowledge, contacts and sources of information. It is not by chance that education is number 4 of the Sustainable Development Goals that replace the so-called Millennium Goals of the United Nations.

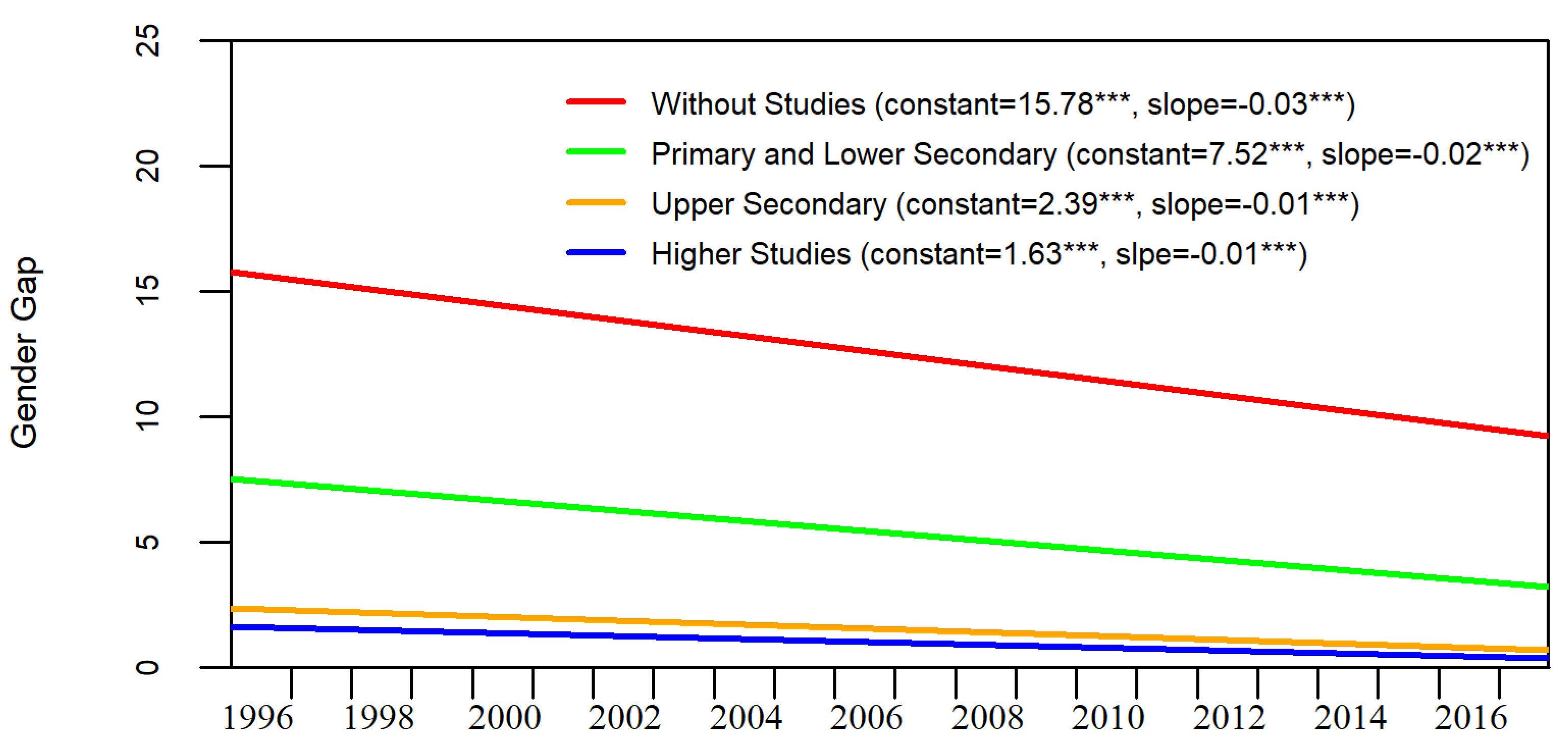

Crossing the variable education with the variable political knowledge supports the argument that the improvement of female human capital directly affects the gender gap in political knowledge, reducing the distance between both genders (

Figure 3). The higher the level of studies, the lower gender gap is in political knowledge. However, the most relevant information for this research provided by the data in

Figure 3 concerns the evolution of the gender gap. According to our thesis, the figure shows that the gender gap in political knowledge has been reduced over these years, as the negative statistically significant slopes corroborate. Despite women having less political knowledge at all educational levels, the gaps have tended to reduce over time. What is more, all groups, whether men or women, academically educated or not, have presented growing trends towards political knowledge. Notably, the most intense trend has been recorded by women without studies.

These data should also be framed in the context of the economic and political crisis that Spain suffered from 2009 onwards. The global financial crisis meant that, over a period of five years, unemployment went from 10% at the beginning of 2008 to 26% in 2013. In this particular framework, with an economic policy of austerity producing great social consequences such as the impoverishment of the middle class [

56], interest in the public agenda intensified. This led to an increase in political knowledge for men and even more so for women. Throughout this period is when both men and women least chose the option “Do not know/No answer”.

The improvement of the educational level of women is equivalent to an increase in female human capital. The labour market is not immune to these changes in education. In the next section, we look closer at the labour market.

4.2. Socioeconomic Status

The massive entry of women into the labour market since the end of the 1980s is another turning point in the sociological transformation of Spain. This was a constant trend up until the years of the financial crisis from 2009 onwards. According to the Survey of Active Population (EPA) of the INE, female presence in the workplace went from less than 40% in 1996 to more than 50% in 2017.

When doing paid work outside the home, women achieve economic independence, a change which has significant social impact [

57]. The life of women is no longer confined to the home but is incorporated into the public space. Their tasks go beyond family obligations. This exposure forces them to be better informed, especially concerning issues related to work, and better understand the functioning of the political system. Contacts are established in the workplace, other interests related to paid work outside the home are incorporated and economic income is obtained. Therefore, entry into the labour market provides women with tangible and intangible resources, fundamental resources for the acquisition of political information.

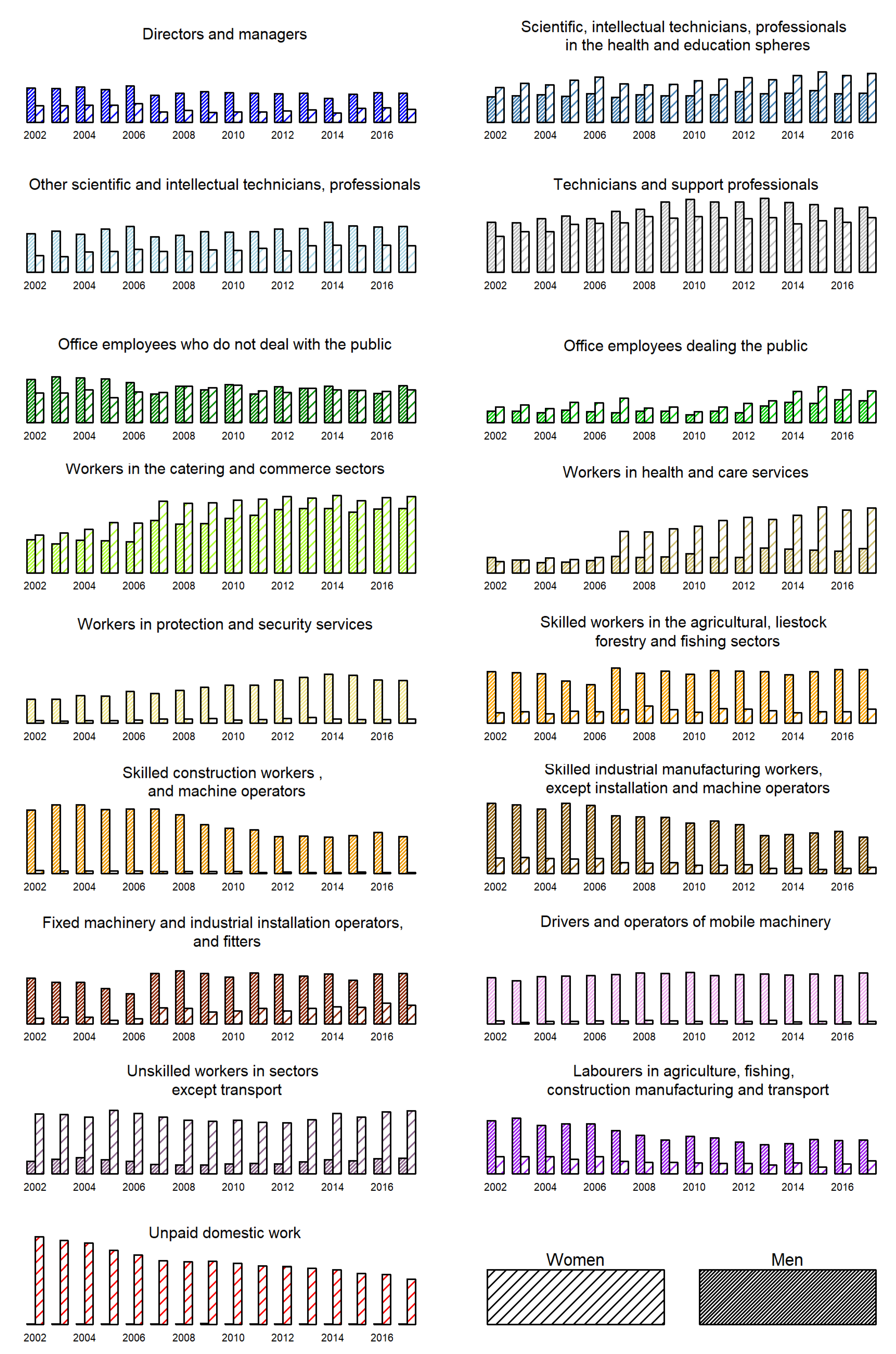

However, this female entry into the labour market offers a constrained economic independence as a result of gender segregation at work (see

Figure 4). Access to cognitive resources in certain labour activities becomes limited due to gender separation in the labour market, either horizontally or vertically [

58,

59,

60].

Firstly, among the four categories requiring higher levels of education (directors and managers, scientific and intellectual technicians and professionals in the health and education spheres, other scientific and intellectual technicians, and professionals and technicians and support professionals), a clear feminization is observed in the health and education spheres. It should be remembered that health and education are two areas where the traditional care functions assigned to the female gender are exercised. Secondly, despite the level of training of women being more or less equal to the preparation of men in recent years, this is not reflected in female presence in the category of directors and managers.

Figure 4 also shows that the majority of workers in the public sector as well as in catering and commerce are women, where high social skills are required to deal with and take care of clients. Similarly, there is a predominance of women in health services and the care of people in general terms. All these are activities directly linked to the gender role of the woman as mother-wife-carer.

Conversely, the female presence in activities related to protection and security services is minimal as well as in the categories of qualified construction workers and machine operators and mobile machinery operators, to mention just two examples. In contrast, in the category of unpaid domestic work, women have a resounding predominance over men.

For the study of the relationship between political knowledge and occupation, some of the occupations have been grouped (see

Figure 5), with a view to making the graphical representations clearer. The criteria used for the grouping are related to the level of qualification of the job and the predominance of male or female workers in the corresponding group.

Figure 5 shows that there is a relationship between the type of occupation and the gender gap in political knowledge. Although historically women are seen to always have a lower rate of political knowledge than men, there is a growing convergent tendency between both genders. According to our thesis, the gender gap is considerably reduced during the analysed period, and this reduction is of higher intensity for less qualified workers, where policies for the empowerment of women have had a stronger impact given the lower levels of political knowledge from which they started. As pointed out by [

61], the gender difference that exists in political knowledge can be reduced.

5. Conclusions

There are many studies analysing the gender gap from different perspectives, with a focus on tangible resources, including wages and labour issues (see, e.g., [

62,

63,

64]). In this paper we adopt a more holistic approach and, by understanding political knowledge as a precursor of women’s empowerment, we study the role of modernization processes.

The process of modernization in Spain has entailed the empowerment of women through intangible resources (education, contacts, information) and tangible ones (economic) with a direct impact on women’s political knowledge, diminishing this gender gap and achieving progress towards a sustainable society. As noted by [

19,

51], the political, economic and socio-cultural modernization of a country is fundamental in achieving equality between men and women. Increasing the level of female education and female participation in the labour market within a legal-political framework attentive to gender equality brings about changes in cultural attitudes towards gender equality that translate into an increase in female political knowledge, reducing the gender gap.

The Spanish modernization means all the socio-economic, political and cultural changes that transformed Spain into a post-industrial country at the end of the 20th century. This includes women’s access to the labour market, legal reforms and gender policy initiatives to secure gender equality and a culture of egalitarian gender roles that transforms the traditional values within the household and family of men as breadwinners and women as caregivers. Indeed, in addition to the effect of individual variables, in our analysis, we also find an effect of contextual variables: the cultural and regulatory change that entails the modernization process. These two contextual variables—egalitarian gender roles and gender equality laws and policies—are two pillars of any inclusive and sustainable society.

This research provides evidence, using longitudinal data, that even when educational level or the occupational status is kept constant, a reduction in the gender gap is seen as a consequence of the process of modernization and the progress towards an inclusive and sustainable society. An inclusive and sustainable society refers to a society that is able to ensure gender-equal access to political participation, economic resources and quality education as well as gender-equal opportunities for employment, leadership and decision-making. This implies gender-equal political participation, where political knowledge is a key resource.

Our results, however, should not be overstated. The measure of political knowledge used shows some limitations related to the meaning of the

‘Do not know’ answers, the multidimensionality of the concept and the fact that different people were surveyed at different times, which may undermine the strength of the conclusions. A better scenario to provide stronger evidence would have been to have a long-term panel study, such as in [

22]. The significance of our study is that we provide evidence that, in the case of Spain, the observed behaviour of the political gender gap, as measured in this research, is compatible with the development theory of Inglehart and Norris and with our subsequent hypothesis. These are also in line with other recent studies in the literature which conclude that

“while gender equality policies are successful in tearing down some of the obstacles that hinder women’s contact with the political world, they are still insufficient to completely bridge the gender gap in political knowledge” [

16]. There is therefore room for improvement and still some way to go.