Abstract

As overtourism has become a serious threat to the tourism industry in recent years, this study attempts to extend the theoretical framework of organization-public relationship (OPR) developed in the public relations scholarship to the context of overtourism. To that end, the concept of place–visitor relationship (PVR) is theoretically suggested and empirically tested in a structural equation model. Also, statistical reliability and validity of PVR are put under investigation. The findings helped confirm the roles and functions of PVR as a potential solution to overtourism in the social media era. As an antecedent, visitors’ affective tour experiences stemming from exposure to social media information significantly influenced PVR. PVR, on the other hand, significantly affected attitudes toward a place and, further, behavioral intentions toward measures against overtourism. In addition, the findings revealed that PVR consists of two sub-factors: Loyalty and relational attachment. Relationship strategies as a solution to the issue of overtourism are discussed in light of PVR.

1. Introduction

Tourism as a pollution-free and never-ending industry is considered simply a myth now. Tourism, more precisely, mass-tourism, has been accused of severe damage to the nature as well as human societies [1]. With the increasing awareness of and concern about tourism’s negative impact to places and communities, several measures have been discussed and implemented worldwide. For instance, the government of Philippines banned tourists’ visits to Boracay for six months due to deteriorating environmental pollution. Venice of Italy, Bali of Indonesia, Edinburgh of Scotland, Dubrovnik of Croatia, along with other famous tour sites are already imposing or planning to impose a visiting tax on tourists [2]. Places such as Salzburg of Austria and Komodo Island of Indonesia are limiting the number of visitors per day [2]. All of the cases point to the side effects of overtourism, which refers to negative impact of tourism occurring from excessive inflow of tourists into a certain place [3].

In such a context, the concept of sustainable tourism has drawn growing interest and attention both from the academia and the industry in recent years. Sustainable tourism, which is derived and evolved from the notion of sustainable development, can be defined as a tourism marketing process in which a balance between visitors’ high-quality tour experiences and the host community’s high quality of life is sought and valued [1,4]. Thus, sustainable tourism “would involve a coordinated attempt to manage the tourism in such a way that the long-term integrity of a region’s natural and human resources will be preserved” [5]. In that sense, sustainable tourism products should be not only environment-friendly and community-respectful, but also economically viable and profitable [6]. To be successful, sustainable tourism requires active engagement and participation of stakeholders [7]. That is, sustainable tourism business models are feasible only when marketers, tourists, and the surrounding community strategically collaborate and build mutually beneficial relationships with one another [8]. In particular, promoting tourists’ eco-friendly, culturally sensitive, and socially desirable behaviors in tour sites is one of the key factors determining success or failure of sustainable tourism [8,9].

As a theoretical framework to understand how to promote tourists’ good behaviors for sustainable tourism, this study looks into the concept of organization-public relationship (OPR) from the public relations scholarship and extends the theoretical concept to the context where visitors and places build and maintain emotional bonding and mutually beneficial relationships. To that end, this study aims to empirically demonstrate the roles and functions of the place–visitor relationship (PVR) in explaining and predicting visitors’ behavioral intentions, such as willingness to pay a visiting tax or voluntary tourist behaviors for environmental protection, to prevent numerous side effects stemming from overtourism. Along this analytic process, construct reliability and validity of place–visitor relationship (PVR), which is assumed to consist of visitors’ relational perceptions about a specific tourism place, is statistically examined as well.

The main purpose of this study, therefore, is to corroborate the theoretical as well as practical utility of PVR in a structural equation model. As potential antecedents of PVR, this study focuses on exposure to place information via social network sites (SNS) and affective tour experiences. Certainly, tourists must visit a specific place in order to develop emotional bonding and PVR. Further, one of the driving forces for tourists to have curiosity and desire to visit a certain place in recent years is tourism information shared, diffused, and consumed through social media platforms [10]. As a sequential process, this study hypothesizes that social media exposure to place information significantly leads to affective tour experiences, and affective tour experiences, in turn, are associated with PVR. It is asserted in this study that PVR as a relational outcome between visitors and a tourism place should result from affective tour experiences facilitated by social media use for tourism information. This study also suggests that PVR as a determinant should influence tourists’ attitudes toward a place and their behavioral intentions for countermeasures against overtourism. By demonstrating such relationships between PVR, attitudes, and behavioral intentions, this study aims to highlight the roles and functions of PVR that can help enhance tourists’ voluntarily eco-friendly behaviors in line with the core philosophy of sustainable tourism. In addition, with a series of factor analyses, the construct validity of PVR and its structural components are identified.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing Place-Visitor Relationship (PVR)

With the growing volume and increasingly intense competition in the tourism industry, building and maintaining mutually beneficial relationships between places and visitors in the long-term have garnered much attention in recent years [11]. When it comes to tourism marketing, the first purchase by consumers (visitors) often occur without a clear understanding of the products (places), while visitors always have many travel destinations to choose from. Places, on the other hand, should compete against other places to attract as many visitors as possible, while too many visitors or visitors with malicious behaviors have increasingly been recognized as uninvited and unwelcoming guests, as in the cases of overtourism [6,12]. For such reasons, relationships between places and visitors have considered a key factor for not only economic viability, but also ecological sustainability [13].

The concept of organization–public relationship (OPR) stemming from the public relations scholarship offers a theoretical framework for place–visitor relationship (PVR). OPR can be defined as a state that exists between an organization and its relevant publics when one’s actions affect the other’s economic, social, and cultural wellbeing [14]. Based the conceptual definition, numerous studies have explored sub-dimensions that constitute OPR. Sub-dimensions of OPR identified so far include trust, satisfaction, control mutuality, and commitment among others [15,16]. Moreover, many scholars have attempted to develop measures to evaluate relationships between an organization and its publics [17,18].

This study attempts to apply the principles of OPR to the context where places and visitors build and maintain mutually beneficial relationships for sustainable tourism. As mentioned earlier, managing relationships between places and visitors has been of important scholarly as well as practical issue, but little discussion has been made to explicate OPR in the context of sustainable tourism. Furthermore, previous literature has paid scant attention to the fact that PVR can be a critical indicator in relation to the issue of overtourism. Taking into consideration that PVR conceptually shows the extent to which visitors care for a certain place, PVR appears to provide a noteworthy starting point for strategic actions against overtourism and sustainable tourism. Based on the previously explored OPR dimensions and measures, this study aims to statistically test reliability and validity of PVR. Thus, the following research questions are to be addressed.

Research Question 1 (RQ1).

Is PVR statistically reliable and valid as a construct meaningful in the context of sustainable tourism?

Research Question 2 (RQ2).

If so, which factors are consisting of PVR to help explain and predict positive consequences in relation to sustainable tourism?

2.2. The Impact of Social Media on Overtourism

The scale of tourism industry has dramatically increased in recent years, thanks to a number of factors [19]. Among such factors, the emergence of social media and consequent overflow of tourism information created, shared, and disseminated online require both scholarly and practical attention, due to its huge impact on the landscape of tourism industry [10,20]. More people gravitate toward, as well as take advantage of, social media, searching for relevant information and expressing their opinions. For example, Facebook, one of the leading social media, had over 1.9 billion users worldwide as of 2017 [21].

Tourism information circulated and sought in such social media has exerted significant influence on tourists’ decision-making and consumer behaviors [20]. Social media have allowed tourists not only to search for information about travel destinations, but also to evaluate online content (i.e., reviews, photos, and videos) related to such places [22,23]. Social media also provides a public sphere where tourists can interact with each other and share their thoughts and feelings. From the perspective of tourism, social media offers a channel as well as platform of interaction and communication where tourists’ opinions and ideas about certain places are actively generated and exchanged. Such an interactive communication process has a significant influence on tourists’ consumer behaviors, specifically in choosing which destination they will visit and spend their leisure time [24,25].

The dark side of social media regarding tourism, however, is that tourists are likely to be exposed to a very limited amount of popular information—due to the power law distribution tendency of social media—so only a handful of places are even more highlighted in such a channel [26]. Such an asymmetry of tourism information exposure, in turn, may help instigate the ‘the rich get richer and the poor get poorer’ phenomenon among places, which is likely to worsen overtourism with more tourists coming into a few limited places. Moreover, social media sometimes expose relatively underexplored and unknown places to a number of users, which may result in business exploitation on such environmentally sensitive places [27]. On one hand, social media may aggravate overtourism by asymmetrical information circulation and exposure, which is likely to attract more visitors to only a handful of already famous and popular destinations [28]. Social media, on the other hand, could be a serious threat to sustainable tourism in general with its widespread and powerful influence [27].

Based on the abovementioned theoretical premise, this study empirically examines the relationship between social media exposure to a certain place and visitors’ travel experiences in the place, particularly focusing on emotional outcomes. Previous studies showed that tourists seek relevant information and upload their postings in social media for emotional purposes [29,30]. A study by Hudson and colleagues [31] demonstrated that tourists’ interaction through social media has a positive effect on their emotional attachment to a tour experience as well as a positive effect on word-of-mouth (WOM) intent. In view of social identity theory, it is also likely that visitors sharing the same information about a certain place may have emotional bonding not only with each other, but also with the place for which they are searching information [32,33]. Thus, this study looks into the effect of social media exposure on affective tour experiences, defined in this study as tourists’ emotional outcomes and evaluation based on actual tour experiences. For such an analytic purpose, the following research hypothesis is suggested.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The degree of visitors’ social media information exposure to a place is positively related to their affective tour experiences in the place.

2.3. The Relationship Between Affective Tour Experiences and PVR

It is important in this study to verify whether PVR is a useful variable by establishing its relationships with potential antecedents and descendants in a theoretical model. By doing so, it can be more strongly argued that PVR is a theoretically meaningful concept in the context of sustainable tourism.

According to the theoretical framework of OPR from which PVR is both conceptually and operationally derived, PVR should be made of visitors’ perceived relationship quality and satisfaction with a certain place [16,34]. In view of such a characteristic of PVR, visitors’ affective tour experiences in a certain place should account for their perceived relationship with the place. Prior research adds theoretical support to such an argument. Actual experiences should determine one’s perceptions and feelings about the relationship counterpart, and such psychologies influence one’s perceived relationship quality as well as satisfaction [35].

Several studies have empirically demonstrated that affective tour experiences are substantial factors for tourists’ psychologies. Pine and Gillmore [36] highlighted the role of tourists’ affective experiences in forming attitudes toward places. Lasalle and Britton [37] argued that positive emotions resulting from tour experiences can elicit tourists’ attachment and loyalty to the places they were traveling. Along the same vein of such findings, many scholars have argued that affective tour experiences can enhance favorable memories of as well as positive attitudes and behaviors toward the place [38,39,40]. Taking into account such literature, it is expected that affective tour experiences are likely to influence the ways in which visitors are forming their perceived relationships with a place they are traveling. This study presumes the following hypothesis accordingly.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Affective tour experiences are positively related to PVR.

2.4. The Consequences of PVR

As OPR has been tested and proved as a reliable and valid concept to evaluate and understand publics’ perceived relationship status and quality with an organization, many scholars have tried to extend the scope of research to exploring the consequences of OPR [41]. Studies along such a research stream have revealed that OPR significantly affects publics’ perceptions, attitudes, and behavioral intentions across a variety of different levels and circumstances [14,42,43].

Considering the main purpose of this study, which aims to demonstrate the utility of PVR as a concept and variable, especially in the context of sustainable tourism, this study puts its analytic focus on visitors’ attitudes toward a place and their behavioral intentions toward protective measures against overtourism as potential consequences of PVR. As mentioned above, visitors’ sustainable and responsible behaviors are one of the key factors essential for the effective implementation of measures against overtourism and, consequently, the success of sustainable tourism. It has been reported that visitors’ environmentally irresponsible and culturally insensitive attitudes and behaviors are the most serious factors aggravating side effects of overtourism [44]. Such an issue was also addressed in recent research by Shen and colleagues [45] looking at the strategic use of SNS to promote visitors’ sustainable and responsible behaviors in a place as a potential means to decrease the problems of overtourism.

In the public relations scholarship, Ki and Hon [43] empirically investigated the impact of OPR on attitudes and behavioral intentions. What is noteworthy in this study is that they designed a research model as a sequential one where OPR affects publics’ attitudes toward an organization, and attitudes, in turn, affect their behavioral intentions toward the organization. In other words, attitude was regarded as a mediator between OPR and behavioral intentions in the study, based on the classic theoretical framework of hierarchy of effects model [46]. Such a hierarchy with attitude as an antecedent of behavioral intentions was advocated in the theory of planned behavior as well [47]. Empirical studies based on such a theoretical assumption have demonstrated that OPR’s influence on publics’ behavioral intentions was mediated by attitudes [48,49].

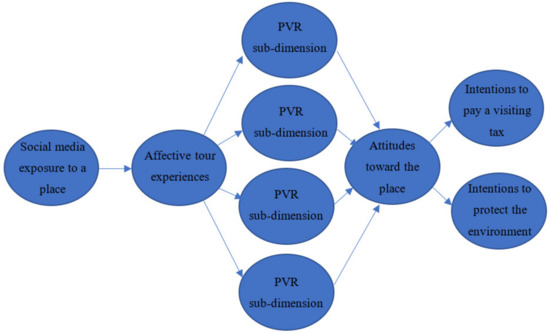

Following the previous literature, this study attempts to empirically confirm the explanatory as well as predictive power of PVR for the variance in visitors’ attitudes toward a place and behavioral intentions toward protective measures against overtourism. Thus, it is hypothesized that PVR should account for visitors’ attitudes toward a place, and visitors’ attitudes toward a place, in turn, should influence their behavioral intentions toward protective measures against overtourism, more specifically, intentions toward paying a visiting tax and behaving in an environmentally friendly manner while traveling. Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized relationships between the variables.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized research model. PVR: Place-Visitor Relationship.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Sub-dimensions of PVR are positively related to visitors’ attitudes toward a place.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Visitors’ attitudes toward a place are positively related to their behavioral intentions toward protective measures against overtourism.

Hypothesis 4-1 (H4-1).

Visitors’ attitudes toward a place positively influence their willingness to pay a visiting tax when entering the place.

Hypothesis 4-2 (H4-2).

Visitors’ attitudes toward a place positively influence their willingness to behave in an environmentally friendly manner when traveling in the place.

3. Research Design and Methods

3.1. Survey Overview

A national survey was designed and conducted in South Korea to empirically collect data and statistically verify the hypothesized relationships among the variables. The survey was executed online through a research company with a country-wide panel. Survey respondents were recruited based on a random quota sampling. During a one-week period of October 2019, a total of 389 respondents completed and submitted reliable and analyzable questionnaires. Table 1 shows the demographics of the research sample.

Table 1.

Sample demographics.

Jeju Island of South Korea was selected as the tourism place for analysis. Jeju Island was chosen for several reasons. First, Jeju Island has been one of the most popular destinations for South Korean tourists for a long time [50]. Hence, Jeju Island has been familiar to most of South Korean tourists as a tourism place. Further, Jeju Island has suffered from overtourism in recent years due to overflow of both domestic and foreign travelers [51]. Through a screening question, it was confirmed that all the survey respondents had visited Jeju Island in person at least once.

3.2. Measurements and Instruments

Referring to previous studies [24,29,52], the degree of respondents’ social media information exposure to Jeju Island was measured by three items using 7-point Likert scales. The items included ‘I get a lot of Jeju Island’s tourist information through social media,’ ‘I frequently get tourist information about Jeju Island through social media,’ and ‘I actively use social media to obtain tourist information about Jeju Island.’

Items to measure affective tour experiences were developed with reference to prior research as well [53,54,55]. Nine items measuring respondents’ affective tour experiences in Jeju Island were ‘I was able to escape from my ordinary life while traveling in Jeju Island,’ ‘I was able to have a good time with my family and friends while traveling in Jeju Isalnd,’ ‘I was able to relieve stress while traveling in Jeju Island,’ ‘While traveling in Jeju Island, I could enjoy various natural landscapes,’ ‘I was able to recharge my life while traveling in Jeju Island,’ ‘I was able to relax my mind and body while traveling in Jeju Island,’ ‘While traveling in Jeju Island, I could enjoy outstanding natural scenery,’ ‘I was able to realize the joy of sightseeing while traveling in Jeju Island,’ and ‘While traveling in Jeju Island, I was able to get closer with my family and friends.’

Meanwhile, items to measure PVR were adopted from previous OPR measures and tourism studies [16,55,56,57]. Items were slightly adjusted in consideration of the context where visitors build and maintain relationships with places. A total of 24 items were used to measure PVR in this study, and the items asked visitors’ perceived loyalty, commitment, attachment, trust, and satisfaction for Jeju Island. Statistical reliability and validity of the items are to be assessed.

For the consequences of PVR, attitudes toward Jeju Island and behavioral intentions toward protective measures against overtourism were evaluated by three seven-point semantic differential scales, respectively. As for attitudes toward Jeju Island, three semantic differential scales (unfavorable–favorable; bad–good; negative–positive) were asked to be marked to measure respondents’ attitudinal responses to Jeju Island [58,59]. In addition, behavioral intentions to pay a visiting tax were measured by three semantic differential scales (unlikely–likely; improbable–probable; impossible–possible), following the statement: ‘To make a better environment, I am willing to pay a visiting tax when traveling Jeju Island.’ Likewise, behavioral intentions to behave in an environmentally friendly manner were measured by three semantic differential scales (unlikely–likely; improbable–probable; impossible–possible), following the statement: ‘I am willing to behave in an environmentally friendly manner when traveling Jeju Island’ [58,59].

4. Research findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Reliability Check

Descriptive statistics indicated that the mean score of social media information exposure regarding Jeju Island was 4.62 (SD = 1.33). The mean score of affective tour experiences was 5.64 (SD = 0.84). On the other hand, the mean score of attitudes toward Jeju Isalnd was 5.47 (SD = 1.08). The mean score of behavioral intentions to pay a visiting tax was 3.82 (SD = 1.52), whereas that of behavioral intentions to behave in an environmentally friendly manner was 5.21 (SD = 1.29).

In addition, three criteria were employed to check statistical reliability of the measurements. Internal consistency reliability, which can be evaluated by Cronbach’s α, was checked for each measurement. Construct reliability (CR) was also verified for each measurement. Further, average variance extracted (AVE) analyses were performed to confirm the degree of variance each measurement can explain. Table 2 shows the results of such reliability analyses. All the coefficients were above the statistical baselines, pointing to each measurement’s satisfactory reliability [60,61].

Table 2.

Reliability test results.

4.2. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses: PVR

A series of factor analyses were executed to demonstrate reliability and validity of PVR as a construct as well as to identify structural components of PVR. First, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted to verify factor loadings of each measurement item, and to identify sub-factors that may constitute the PVR construct. Second, a confirmatory factor analysis was performed to reaffirm statistical validity of each sub-factor and measuring items.

For the exploratory factor analysis, a maximum likelihood method was chosen for factor extraction [62]. As to rotation method, varimax rotation was employed as one of the most commonly available orthogonal methods [63]. The analysis showed that two sub-factors statistically stood out among the 24 items used to measure the PVR construct. The first factor of PVR consisted of 13 items. The first factor (M = 4.56, SD = 0.96) was named ‘loyalty’ in this study, since most of the 13 items were used to measure loyalty to a tourism destination in previous studies. The second factor (M = 5.28, SD = 1.00) consisted of seven items. As items used to measure trust, satisfaction, and commitment were mingled in this factor, this study named the factor ‘relational attachment.’ Internal consistency reliability of each factor, measured by Cronbach’s α, was statistically satisfactory as well. Among 24 items employed to measure PVR in the first place, 4 items were finally excluded, due to their low factor loadings and lack of communality. Table 3 summarizes the results of the factor analysis.

Table 3.

Exploratory factor analysis.

Convergent and discriminant validity of the two sub-factors of PVR were examined. The average variance extracted (AVE) value of ‘loyalty’ was 0.61, which was over 0.5, and its construct reliability (CR) value was 0.95, which was over 0.7, all of which met statistical standards to assure convergent validity [64]. Likewise, convergent validity of ‘relational attachment’ was confirmed (AVE = 0.64; CR = 0.92). Discriminant validity was also checked by demonstrating whether the AVEs of the sub-factors are greater than the square of correlation coefficient between the two (0.60). With such a criterion, discriminant validity of the two sub-factors was confirmed as well [65].

In addition, statistical validity of the two sub-factors of PVR was demonstrated by a confirmatory factor analysis. The first factor (loyalty) model with 13 items and the second factor (relational attachment) model with 7 items were under scrutiny. The results of goodness-of-fit analyses for each model are described in Table 4.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

As described in Table 4, goodness-of-fit for each model was statistically satisfactory. For each model, the values of root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were below 0.06, and other indices, including goodness-of-fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), and Turker-Lewis index (TLI) were over 0.9, which signaled statistically significant construct validity of PVR [66,67]. Overall, PVR was reliable and valid as a theoretical construct, according to a series of statistical tests, and it appeared to consist of two sub-factors, which were loyalty and relational attachment.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling and Path Analyses

Apart from statistical reliability and validity of the PVR construct, scholarly as well as practical utility of PVR was inspected by establishing its relationships with other theoretically relatable variables in a structural equation model. More specifically, the hypothesized model attempts to demonstrate whether loyalty and relational attachment, which were identified as two sub-factors composing PVR, are influenced by visitors’ affective tour experiences stemming from exposure to social media information about Jeju Island. In addition, loyalty and relational attachment are expected to positively influence attitudes toward Jeju Island, and attitudes toward Jeju Island, in turn, are hypothesized to facilitate counter-overtourism behavioral intentions.

As the first step to demonstrate the utility of PVR, statistical appropriateness of the structural equation model was estimated. Goodness-of-fit was estimated with several statistical coefficients. χ2 was 1452.81 (p < 0.01), and degree of freedom was 743 (χ2/df = 1.96). RMSEA (0.050), which was less than 0.06, signified statistical appropriateness of the model [66]. Furthermore, NFI (0.914), IFI (0.956), TLI (0.951), and CFI (0.956) were all over 0.90, which also confirmed statistical appropriateness of the model [68]. Overall, statistical appropriateness of the model was verified.

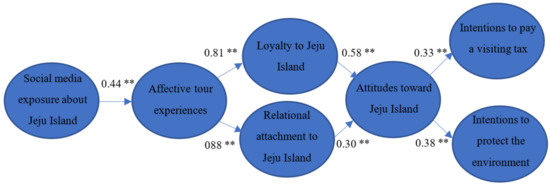

In addition, path analyses were performed to test statistical significance of the relationships between the variables. As shown in Figure 2, all the regression weights for the paths were statistically significant at the 0.01 level, which supported all the hypotheses suggested by the study. As theoretically assumed, the degree of exposure to social media information about Jeju Island had significantly positive influence on visitors’ affective tour experiences. Affective tour experiences, on the other hand, were significantly as well as positively associated with the two sub-factors of PVR, loyalty and relational attachment to Jeju Island. In other words, the more visitors were affectively satisfied with their tour experiences in Jeju Island, the stronger they felt loyalty and relational attachment to Jeju Island. Meanwhile, PVR elicited more positive attitudes toward Jeju Island, and positive attitudes toward Jeju Island, in turn, led to visitors’ favorable behavioral intentions to curb side effects of overtourism, such as willingness to pay a visiting tax and to behave in an environmentally friendly manner.

Figure 2.

Structural equation modeling. ** Path significance: p < 0.01.

Table 5 shows the direct and indirect effects of independent variables on dependent variables in the model. As demonstrated from the path analyses, both social media exposure and affective tour experiences directly as well as indirectly affected the two sub-factors of PVR, loyalty and relational attachment to Jeju Island. Also, attitudes toward Jeju Isalnd were directly as well as indirectly influenced by social media exposure, affective tour experiences, and PVR. By the same token, willingness to pay a visiting tax and to behave in an environmentally friendly manner were influenced by the preceding variables both directly and indirectly.

Table 5.

Direct and indirect effects.

5. Discussion

A series of factor analyses helped confirm statistical reliability and validity of the construct of PVR as a theoretical extension of OPR to the context where a place and visitors build and maintain mutually beneficial relationships. Further, the analyses helped shed light on the structural components of PVR, which are loyalty and relational attachment to a place. According to the findings, visitors perceive their relationships with a place particularly in association with their loyalty and relational attachment to a place. To the extent the concept of OPR has contributed to the public relations scholarship, it appears that PVR could help advance the body of knowledge for the tourism scholarship by helping explain and evaluate the dynamics of relationships built and retained between a place and visitors.

Also, scholarly and practical utility of PVR was demonstrated by establishing its connections to theoretically meaningful antecedents and descendants. Specifically, PVR in this study was considered one of the sustainable solutions to overtourism, for PVR is conceptualized as a state in which visitors value their relationships with a place and care about the place’s wellbeing [14,16]. In other words, PVR is considered an influential motive for visitors to behave in accordance with the principles of sustainable development in a certain place. Moreover, the roles and functions of PVR were theorized and articulated in consideration of the impact of social media on the tourism industry in recent years.

As demonstrated by numerous previous studies [28,69,70], it turned out in this study that social media has a substantial effect on visitors’ perceived tour experiences. More specifically, this study empirically found that the degree of exposure to social media information about a certain place could positively influence visitors’ emotional outcomes associated with their actual tour experiences. A statistically significant influence of social media exposure on affective tour experiences indicated that information posted, shared, and spread in social media about a place can not only attract more visitors to the place, but also enhance visitors’ affectively satisfying tour experiences and emotional outcomes. In fact, exposure to social media information about a certain tourism place can offer diverse ways of social or parasocial interaction where emotions and experiences are exchanged and amplified between the place and visitors even before arrival [28]. Such social interaction between a place and visitors can lead to more satisfactory perceptions and responses with regard to tour experiences [71].

Visitors’ affective tour experiences, on the other hand, were positively associated with the two sub-dimensions of PVR, loyalty and relational attachment. The more satisfactory were visitors’ affective tour experiences in Jeju Island, the stronger they perceived loyalty and relational attachment toward the place. Not only do such findings intuitively make sense, but they are in parallel with prior literature highlighting the role of actual interaction and experience between two parties in the making of a relationship [72,73]. Certainly, a relationship requires actual interaction between two parties. Perceptions of such a relationship are subject to actual experiences of each other’s interactive behaviors. Also, it is noteworthy that such firsthand tour experiences are more powerful and influential than simple information exposure in social media in explaining the variances in PVR. The findings shed light on the possibility that visitors are likely to form and develop PVR, such as loyalty and relational attachment to Jeju Island, as they have quality tour experiences at an emotional level.

Loyalty and relational attachment to Jeju Island, in turn, had a significantly positive influence on visitors’ attitudes toward Jeju Island. Referring to previous studies [17,41,43], this study theorized attitudes toward a place as a dependent variable of PVR, and, as hypothesized, visitors’ attitudes toward Jeju Island, which conceptually reflect visitors’ emotional judgment for the place, were significantly affected by the level of loyalty and relational attachment. Visitors’ attitudes toward Jeju Island tend to get better as a result of their stronger loyalty and relational attachment to the place. This study empirically demonstrated the role and function of PVR in explaining and predicting visitors’ attitudes toward a place.

In addition, visitors’ attitudes toward Jeju Island were significantly related to visitors’ behavioral intentions to alleviate side effects of overtourism. Based on the hierarchy of effects model and theory of planned behavior, this study hypothesized that attitudes toward Jeju Island will lead to visitors’ willingness to support countermovement against overtourism. The findings showed that visitors are more likely to pay a visiting tax as well as to voluntarily protect the environment of Jeju Island if they maintain more positive and favorable attitudes toward the place. Moreover, according to the structural equation model, PVR indirectly affected such behavioral intentions through attitudes. Thus, the relationships between the two sub-dimensions of PVR and behavioral intentions were mediated by attitudes toward Jeju Island. In sum, PVR can elevate attitudes toward a place, which, in turn, positively encourage visitors to behave against overtourism.

Such a result demonstrated the roles and functions of PVR as a sustainable solution to overtourism. It has been well-documented that quality OPR helps establish a sustainable and mutually beneficial environment both for an organization and its publics [14,16,34]. Likewise, this study showed that PVR can be an effective indicator for such a sustainable relationship built and maintained between a place and its visitors. Scholars and practitioners alike have discussed numerous approaches and strategies to deal with problems arising from overtourism. No such measures can be successful, however, unless visitors take the problem of overtourism seriously and act responsibly and voluntarily to solve such problems from the perspective of a relationship partner. PVR can be understood as an indicator to gauge visitors’ willingness to protect the environment of a certain place and, further, to safeguard the longevity of mutually beneficial relationships with the place. The more so visitors value and cherish their relationships with a place, the more likely they act in favor of protecting and supporting the place and its community.

From a strategic and practical viewpoint, therefore, places need to enhance and strengthen visitors’ perceived relationships. Public relations strategies and tactics could be useful not only for measures against overtourism, but also for place marketing and tourism in general. When a place is recognized as unique, special, and irreplaceable, visitors are likely to cherish their relationships with such a place. An emotional appeal is important for PVR as demonstrated in this study. Personification of a place could be an effective approach to promote visitors’ perceived relationships as well. According to the findings, sustainable tourism with economic viability as well as environmental preservation calls for visitors’ loyalty and relational attachment to a place.

6. Conclusions

The problems and conflicts caused by overtourism have become a serious threat to the tourism industry. Such problems and conflicts are of particular significance, because they can possibly destroy mutually beneficial relationships between visitors and residents living in the local community [74]. As seen from various cases, local residents do not welcome too many visitors into their territory and do not appreciate any potential depletion or pollution caused by excessive tourist traffic. Some extremists have protested against tourism and have even manifested acts of vandalism [75]. Visitors, on the other hand, are likely to feel intimidated and insulted from such reactions from the locals. Certainly, such experiences may prevent visitors from considering revisit or posting positive word-of-mouth on social media. Within such a process, overtourism hampers sustainable tourism.

What is ideally critical to solve such problems and conflicts, therefore, is mutual understanding and respect between visitors and a local community. PVR suggested in this study came from such a recognition. Based on the theoretical framework of OPR, PVR helps indicate and evaluate visitors’ perceived relationship quality with a certain place. It also helps understand visitors’ psychological structures regarding their perceived relationships with a place. According to the empirical findings of this study, visitors of Jeju Island perceive their relationships with the place in terms of loyalty and relational attachment. As long as visitors possess loyalty and relational attachment to Jeju Island, it is not likely that they cause too much damage to the local community. The local community, on the other hand, is likely to welcome and appreciate visitors’ goodwill and responsible behaviors while traveling. Theoretically speaking, such mutually beneficial relationships built and maintained between visitors and a place should be an effective solution to problems and conflicts caused by overtourism.

Although this study presents a relatively new and fresh perspective looking at the issue of overtourism, it should be mentioned that this study has several methodological limitations as well. Despite the nation-wide survey based on random quota sampling, generalizability is still an issue, since survey respondents were recruited from a pool constructed and managed by a research company. External validity, therefore, should be tested again elsewhere with a more representative sample. An analysis in a different cultural context, with different units of observation could strengthen external validity of the findings. Additionally, the utility of PVR can be tested and demonstrated within a different theoretical model, taking into account PVR’s relationships with other meaningful variables, such as word-of-mouth, donation to a community, or other eco-friendly behaviors. Future studies could be designed and implemented along such a line of research.

Author Contributions

H.M.L. held the leading position in writing, while Y.N. and J.P. supported writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Conceptualization, H.M.L. and Y.N.; methodology, H.M.L., Y.N., and J.P.; data curation, H.M.L. and J.P.; formal analysis, Y.N. and J.P.; investigation, H.M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.N. and J.P. funding acquisition, H.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Sungshin Women’s University Research Grant of 2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Choi, H.C.; Sirakaya, E. Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism: Development of sustainable tourism attitude scale. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Overtourism? Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, G. Sustainable Tourism Development: Guide for Local Planners; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dinan, C.; Sargeant, A. Social marketing and sustainable tourism: Is there a match? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso, S. Adoption of voluntary environmental tools for sustainable tourism: Analyzing the experience of Spanish hotels. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V.M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J. A framework of approaches to sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 1997, 5, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F. A new approach to sustainable tourism development: Moving beyond environmental protection. Nat. Resour. Forum. 2003, 27, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Adapting to the mobile world: A model of smartphone use. Anna. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conze, O.; Bieger, T.; Laesser, C.; Riklin, T. Relationship intention as a mediator between relational benefits and customer loyalty in the tour operator industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S. Determinants of market competitiveness in an environmentally sustainable tourism industry. J. Travel Res. 2000, 38, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.A. Customer relationship management in tourism: Management needs and research applications. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruning, S.D.; Ledingham, J.A. Relationships between organizations and publics: Development of a multidimensional organization-public relationship scale. Public Relat. Rev. 1999, 25, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, L.C.; Brunner, B. Measuring public relationships among students and administrators at the University of Florida. J. Commun. Manag. 2002, 6, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H. OPRA: A cross-cultural, multiple-item scale for measuring organization-public relationships. J. Public Relat. Res. 2001, 13, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, E.J.; Hon, L.C. Reliability and validity of organization-public relationship measurement and linkages among relationship indicators in a membership organization. J. Mass. Commun. Q. 2007, 84, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruning, S.D.; Galloway, T. Expanding the organization-public relationship scale: Exploring the role that structural and personal commitment play in organization-public relationship. Public Relat. Rev. 2003, 29, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Thal, K. The impact of social media on the consumer decision process: Implications for tourism marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallas, P. Top 15 Most Popular Social Networking Sites (and 10 apps!). Available online: https://www.dreamgrow.com/top-15-most-popular-social-networking-sites/ (accessed on 23 November 2019).

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M.; Christou, E.; Gretzel, U. Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality: Theory, Practice and Cases; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, N.; Koo, C. The use of social media in travel information search. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, E.; Kim, J.K. Comparing the attributes of online tourism information sources. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.C.; Wang, Y.; Vestal, A. Power asymmetries in tourism distribution networks. Anna. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 755–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkono, M. Sustainability and indigenous tourism insights from social media: Worldview differences, cultural friction and negotiation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.; Borrajo-Millan, F.; Yi, L. Are social media data pushing overtourism? The case of Barcelona and Chinese tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Lopez, E.; Bulchand-Gidumal, J.; Gutierrez-Tano, D.; Diaz-Armas, R. Intentions to use social media in organizing and taking vacation trips. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Roth, M.S.; Madden, T.J.; Hudson, R. The effects of social media on emotions, brand relationship quality, and word of mouth: An empirical study of music festival attendees. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.J.; McQuitty, S. Attitudes and emotions as determinants of nostalgia purchases: An application of social identity theory. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2007, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, G.M.; Casey, S.; Ritchey, J. Toward a concept and theory of organization-public relationships. J. Public Relat. Res. 1997, 9, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorvoreanu, M. Online organization-public relationship: An experience-centered approach. Public Relat. Rev. 2006, 32, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, J.; Gillmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lasalle, D.; Britton, T.A. Priceless: Turning Ordinary Products into Extraordinary Experiences; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G.; Baloglu, S.; Brewer, P.; Qu, H. Consumer e-loyalty to online travel intermediaries. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2009, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Witham, M. Dimensions of cruisers’ experience, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruning, S.D.; Lambe, K. Relationship building and behavioral outcomes: Exploring the connection between relationship attitudes and key constituent behavior. Commun. Res. Rep. 2002, 19, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruning, S.D.; Ledingham, J.A. Organizatioanl-public relationships and consumer satisfaction: The role of relationships in the satisfaction mix. Commun. Res. Rep. 1998, 15, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, E.; Hon, L.C. Causal linkages among relationship quality perception, attitude, and behavior intention in a membership organization. Corp. Commun. 2012, 17, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The attitude-behavior gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Sotiriadis, M.; Zhou, Q. Could smart tourists be sustainable and responsible as well? The contribution of social networking sites to improving their sustainable and responsible behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidge, R.; Steiner, G.A. A model for predictive measurement of advertising effectiveness. J. Mark. 1961, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruning, S.D.; Ralston, M. The role of relationships in public relations: Examining the influence of key public member relational attitudes on behavioral intent. Commun. Res. Rep. 2000, 17, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, E.; Hon, L.C. Testing the linkages among the organization-public relationship and attitude and behavioral intentions. J. Public Relat. Res. 2007, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Thapa, B.; Kim, H. International tourists’ perceived sustainability of Jeju Island, South Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Kim, M.; Chang, M.; Koo, B. Evaluation on overtourism in Jeju Island. J. Tour. Ind. Res. 2019, 39, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkmans, C.; Kerkkhof, P.; Beukeboom, C.J. A stage to engage: Social media and corporate reputation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Cia, L.A. Travel motivations and destination choice: A study of British outbound market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 13, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Lee, C.; Klenosky, D.B. The influence of push and pull factors at Korean national parks. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.A.; Sohail, M.S. Festival tourism in the United Arab Emirates: First-time versus repeat visitor perceptions. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressgrove, G.N.; McKeever, B.W. Nonprofit relationship management: Extending the organization-public relationship to loyalty and behaviors. J. Public Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E.; Suci, G.J.; Tannenbaum, P.H. The Measurement of Meaning; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Asplund, K.; Norberg, A. Caregivers’ reactions to the physical appearance of a person in the final stage of dementia as measured by semantic differentials. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1993, 37, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Method. 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Reidy, J.; Keogh, E. Testing the discriminant and convergent validity of the mood and anxiety symptoms questionnaire using a British sample. Person. Individ. Diff. 1997, 23, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zait, A.; Bertea, P.E. Methods for testing discriminant validity. Manag. Mark. 2011, 9, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.Z.; Bentler, P.M. Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginners’ Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tham, A.; Croy, G.; Mair, J. Social media in destination choice: Distinctive electronic word-of-mouth dimensions. Soc. Med. Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B.; Chen, W. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Chung, Y.; Weaver, P.A. The impact of social media on destination branding: Consumer-generated videos versus destination marketer-generated videos. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, V.S. Understanding the donor experience: Applying stewardship theory to higher education donors. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.U. An integrated model for organization: Public relational outcomes, organizational reputation, and their antecedents. J. Public Relat. Res. 2007, 19, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyslony, P.; Kowalczyk-Aniol, J.; Dembinska, M. Deconstructing the overtourism-related social conflicts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.M.M.; Martinez, J.M.G.; Fernandez, J.A.S. An analysis of the factors behind the citizen’s attitude of rejection towards tourism in a context of overtourism and economic dependence on this activity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).