1. Introduction

There is a growing interest and demand for sustainable food production [

1] due to a growing concern of environmental pollution and climate change. In this vein, the topic of sustainability in agriculture is the subject of debate not only for the experts in the industry but also for government officials and researchers [

2,

3]. Sustainable agriculture refers to the way in which natural resources are used efficiently without depleting or damaging them in the short term [

4]. It also refers to a production method that reduces the effects of pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions that can occur when producing crops or raising livestock [

5]. Sustainability in agriculture in the early 1990s was aimed at protecting land for permanent agricultural production [

6]. However, as the population grew and the economy developed in the early 2000s, research focused on the efficient use of finite natural resources on Earth [

7]. In recent years, studies on the sustainability of agriculture considered ways to cope with population growth, changes in consumption patterns, and ways to reduce the impact of agriculture on the environment, such as climate change. Sustainable intensification in agriculture, which refers to a process or system where agricultural yields are increased without adverse environmental impact or the conversion of additional nonagricultural land [

8], has been highlighted too.

The livestock industry, including dairy farming, has a relatively greater environmental impact compared to other agricultural sectors, such as crop production [

3,

9,

10]. As income increases and urbanization progresses, the demand for meat and dairy products increases [

11], and the increase in livestock production resulting from increased demand causes environmental problems, such as pollutants from raising livestock and waste from the slaughtering and distribution process [

12]. Problems that may arise from livestock production include both direct problems, such as soil pollution from livestock manure, water pollution, air pollution from ammonia, and the effects of climate change from methane and nitrogen emissions, and indirect problems, such as disease risk due to pathogenic viruses from the bacteria remaining in the manure [

13].

Based on the consensus regarding the importance and necessity of sustainable livestock farming, many countries have established plans for promoting sustainable livestock farming in various ways, and policies and researches are also underway to support the plans [

3,

10]. In recent years, the agricultural and livestock industries have developed with a focus on efficiency, such as by increasing the production of agricultural and livestock products. However, as concerns about environmental pollution have increased, interest is increasing in food safety and sustainability, as well as efficiency in the production side. In the case of Korea, mountainous livestock and dairy farming are being promoted as examples of sustainable farming. Unlike the traditional cage farming in Korea, mountainous livestock and dairy farming are a natural breeding system in which cattle are grazed in mountainous areas, and their excrements are used as a natural organic fertilizer for the production of forage. Also, natural purification through large mountain ranges minimizes the impact on the environment caused by greenhouse gases. In the case of conventional cage breeding, it is not possible to naturally purify the greenhouse gas emitted by large numbers of livestock raised in a limited space, but it is possible for farming that uses a large space in the mountainous area. In the case of dairy farming that incarnates animal welfare, which has been introduced in recent years, the living space of livestock is being expanded by utilizing a relatively larger space than conventional cage breeding, however, it does not solve the fundamental problem of the emission of greenhouse gases and their purification [

14]. Therefore, mountain farming is classified as a representative type of sustainable livestock and dairy farming in Korea [

15]. Sustainable farming is not only considering the efficient use of natural resources and their environmental impact, but it is also expected to meet consumer needs related to safe and clean livestock and dairy products and animal welfare, which are increasing of interest to consumer in recent years [

16].

A number of studies have been conducted on the necessity and requirements for sustainable livestock and dairy farming [

17,

18], such as researches on the production, processing, and distribution efficiency of livestock products [

19,

20]; problems raised during the production of livestock products [

21]; livestock and milk-consumption patterns; and consumer preferences [

22,

23,

24]. However, it is hard to find a study that analyzed consumers’ perceptions of sustainable farming and the preference for livestock and dairy products produced through sustainable farming. Consumers’ behavior purchasing products produced through sustainable farming is intrinsically connected with sustainable consumption, which is defined as the consumption that results in minimal environmental impacts in spite of satisfying basic human needs. In this sense, the present study is a good reference for the future study of sustainable consumption.

The present study focused on white milk, one of the representative dairy products, with general attributes such as type of milk, brand, price, and remaining shelf life, as well as being produced through mountainous dairy farming. The analysis was conducted with the assumption that white milk was the basic product. There are various processed milks besides white milk, but white milk, which has the highest consumption and the lowest processing level, was selected for the study. In this study, we examined consumers’ preferences for the aspect of sustainability in the milk and the change in the consumers’ preferences according to the awareness of sustainable dairy farming. Using scenario analysis for product attributes, we estimated the preference share that corresponded to the change of each attribute.

2. Methodology

Choice Experiment (CE) was one of the stated preference methods for evaluating the monetary value. It is most commonly used to analyze consumer’s willingness to pay, along with contingent valuation and experimental auctions [

25,

26]. CE is based on the random utility model, which combines the attributes of a certain product to create a hypothetical product and to analyze consumer choices. In other words, in this approach, the consumer’s choice is based on the selection of the best alternatives that maximizes utility. CE can be used to estimate the willingness to pay for each attribute, and probability calculations can be used to estimate preference share [

27]. This study estimated the willingness to pay for the attributes of milk by using the random utility model and by applying the conditional logit model for its estimation.

The utility (

) that a consumer

obtains from a choice alternative

in the alternative set (

) can be expressed as Equation (1):

where the utility (

) of the consumer

can be divided into the observable deterministic part

and the unobservable stochastic part

, with

being the attribute vector of the alternative

j. The observable utility (

) is expressed by the multiplication of the attribute vector (

) and the coefficient vector (

) for each alternative

j. If the consumer

selects the alternative

between the specific choice alternative

and other option

, the utility relationship of the consumer

is established as

. In this case, the probability of the consumer

choosing an alternative

is shown in Equation (2):

If we assume that the error terms are independently as well as identically distributed and we follow the extreme value distribution, the probability

that the consumer

will choose

among the total of the alternatives

can be expressed as shown in Equation (3) [

28]:

Assuming that the observable part of the utility function

is a linear function, it can be expressed as Equation (4), where

is

th attribute in the attribute vector

:

We can derive the consumers’ willingness to pay standards (

) and the partial value of each attribute by applying empirical regression, such as the conditional logit model. In this case, the willingness to pay standards and the marginal willingness to pay (

) for each attribute can be derived using Equations (5) and (6):

where

is the dummy variable for the selected alternative,

is the mth attribute variable, and

is the price attribute variable. In the empirical estimation, no choice option can be allowed as one of the presented choice alternatives, which is called the alternative specific constant (ASC). The ASC variable equals to 0 when any of the choice alternative is chosen, and it equals to 1 when none is chosen.

4. Estimation Results

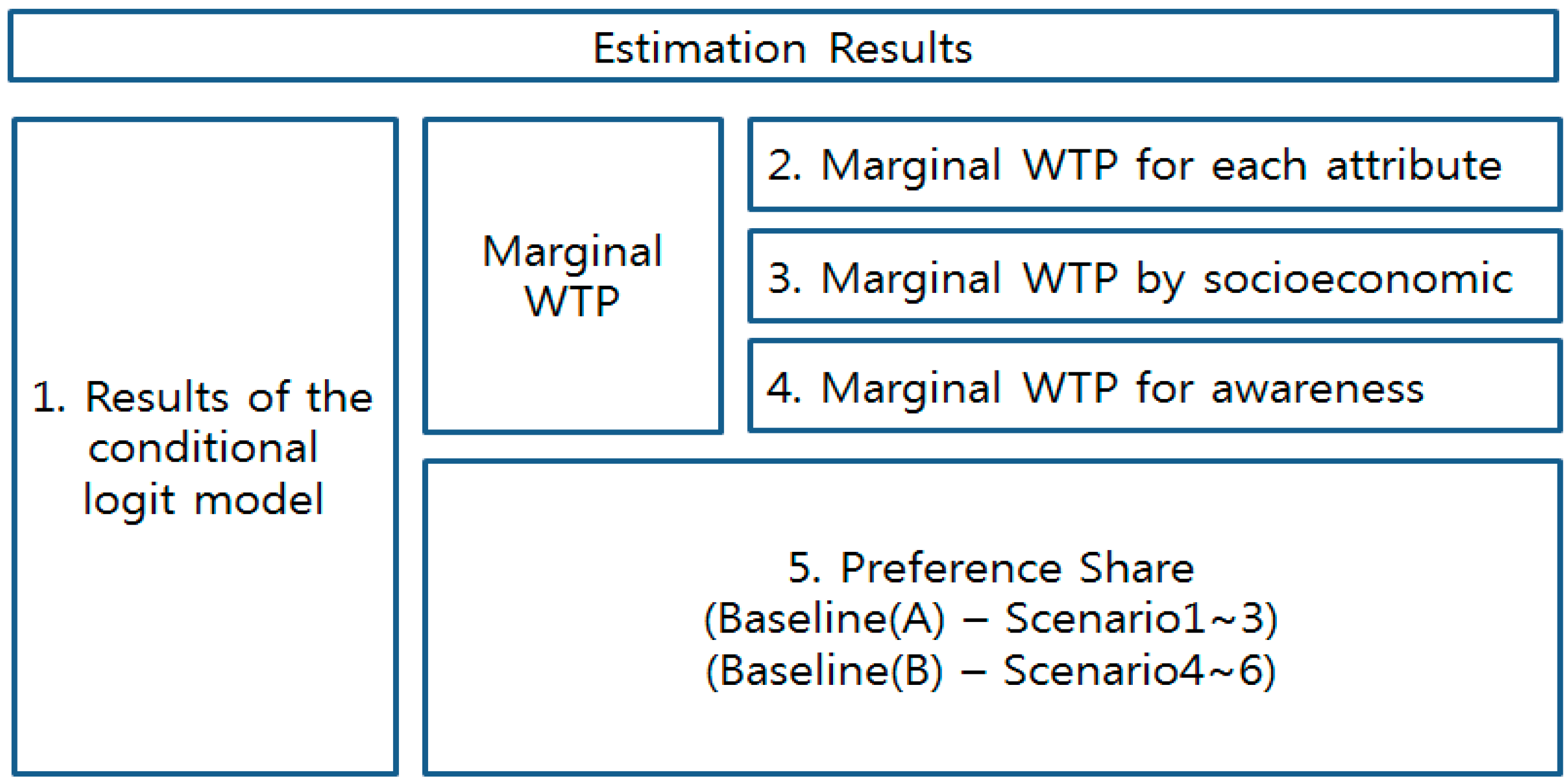

As indicated by

Figure 1, the results of this study are divided into two categories: the estimation of marginal willingness to pay (WTP) and the estimation of the share of preference of consumers based on the conditional logit model estimates. The following three steps illustrate how marginal WTP and the change in the preference share of consumers, according to changes in milk type and production methods, were estimated. First, three different marginal WTPs were estimated and compared according to the attributes of milk, the socioeconomic characteristics of consumers, and the level of awareness of mountainous dairy farming. Second, consumers’ preference shares for 16 hypothetical alternative milk products presented in this study were estimated. Third, based on the estimated preference shares, scenarios were set and analyzed for investigating the changes in the preference share of milk if different level of attributes were realized and if the production method was changed to mountainous dairy farming.

4.1. Results of the Conditional Logit Model

Using the consumer survey data, the results of the conditional logit model were estimated by using the maximum likelihood method. The goodness-of-fit test result of the model was 2373.5, which was greater than the threshold of 1% significance level 21.67 (degree of freedom 9), therefore, we rejected the null hypothesis that all estimated coefficients (

) were zero (

Table 4). Of the variables applied in the estimation, “remaining shelf life” and “price” were included as continuous variables, while other variables were included as dummy variables [

31]. In the case of “milk type”, regular milk was excluded as a reference, and for “production method” and “brand”, traditional cage dairy farming and other brands were excluded.

According to the estimation results, most coefficients except low-fat milk of the “milk type” attribute and the Namyang Dairy of the “brand” attribute were estimated to be significant at the 1% level. In the case of “price” variables, the partial value of the property (

) decreased as the estimated coefficient turned out to be −0.002, which was consistent with the general economic theory [

32]. As for the result of analyzing the “remaining shelf life” attribute, the value of milk increased by 0.167 as the remaining shelf life increased by one day. The value of high-calcium milk was estimated to be 0.274 higher than the value of regular milk, and the value of milk produced through mountainous dairy farming was 1.282 higher than that produced through traditional cage farming. Lastly, the value of Seoul milk, the top milk brand in Korea, was estimated to be 0.539 higher, and the value of Maeil Dairy, the second biggest milk company in Korea, was 0.316 higher than that of other brands’ milk.

4.2. Marginal Willingness to Pay for Each Attribute

Utilizing the estimation results of the model, marginal willingness to pay is calculated in

Table 5. Based on the alternative specific constant captured by the “no-choice” dummy variable, the milk with the attributes of regular milk, traditional cage farming, other brands, and the remaining shelf life of two days was estimated to be

$1.88 per liter. According to the results of willingness to pay by attribute level, consumers were willing to pay

$0.14/L,

$0.28/L, and

$0.16/L more for high-calcium milk, Seoul milk, and Maeil milk compared to regular milk and other brands, respectively. In addition, consumers were more likely to pay

$0.06/L for low-fat milk, but it was not statistically significant at the 10% level. Consumers were willing to pay

$0.67/L and

$0.09/L more for the milk produced by mountainous dairy farming than by traditional cage farming and when the remaining shelf life increased by one day.

In this study, the increase in the willingness to pay for the production method of mountainous dairy farming (sustainable way of production) was about 31.0% to 41.3% higher compared to that of conventional cage farming depending on the suggested price. This increasing rate was well within the range of WTPs estimated in previous studies for investigating the attribute of sustainability of food production. For example, the estimated increasing rate for WTP of the attribute of mountainous dairy farming in this study was higher than that of 12.9% from the result of a previous study for wine [

33]. In the result of previous studies on the same product, white milk, it was analyzed that consumers are willing to pay a 90.6% higher price for organic milk than that of conventional milk [

34]. The difference in WTP between the previous and present studies can be interpreted as a result of the differences in considered product characteristics (such as degree of processing, maturation, variety, etc.), surveys, and estimation methods. However, the present and previous studies consistently yielded the same results, where a higher WTP for the food product, in which sustainability is embedded, was revealed. Comparing the result of marginal willingness to pay for each attribute of milk, consumers showed a higher willingness to pay for high-calcium and low-fat milk than regular milk, and Seoul milk was revealed to be the most preferred milk brand. Among the estimation results, it was remarkable that the marginal willingness to pay was the highest for the attribute of mountainous dairy farming. It implies that consumers very much care about sustainability in milk production. These results show that the considerations of consumers’ recent food choices are not limited to nutrients or brands, but they place a greater emphasis on food safety, environmental conservation, and sustainability.

4.3. Marginal Willingness to Pay by Socioeconomic Characteristics

The amount of marginal willingness to pay was estimated by classifying consumers according to demographic characteristics (

Table 6). First, the results of categorizing consumers by gender showed that women were willing to pay more for high-calcium milk, milk produced through mountainous farming, and well-known brands. For example, women were willing to pay

$0.16/L more and men were willing to pay

$0.13/L more for high-calcium milk than regular milk. It was estimated that women were willing to pay

$0.82/L more for the milk produced by mountainous farming than traditional cage one, which was

$0.27/L higher than that of men (

$0.55/L).

The WTP for high-calcium, low-fat, mountainous farming, and well-known brands (Seoul and Maeil) were higher as the age got younger. This result is linked to a change in the pattern of food consumption. Dairy products are not traditional food in Korea. However, as food habit becomes westernized as income grows, more younger people are consuming milk. Therefore, younger consumers care more about the issue of health and food safety of milk, compared with older generatiosn. In families with children under the age of eight, the WTP for attributes related to the environment and food safety was higher than those without children. Families with children under the age of eight were estimated to pay $0.77/L more for the milk through mountainous dairy farming, which was about $0.13/L more than the one for families without children ($0.64/L). As the remaining shelf life increased by one day, the marginal WTP of families with children under the age of eight amounted to $0.13/L, which was about $0.05/L higher than those without children ($0.08/L).

Analyzing by the income level, households with higher incomes had higher marginal WTP for high-calcium, low-fat, and mountainous farming than those with low incomes. Comparing the amount of marginal WTP by the number of household members, no special pattern was found in most of the attributes. However, WTP for the remaining shelf life decreased as the number of households got larger. This can be interpreted as households with a large number of people tend not to consider the remaining shelf life due to the high milk consumption, which is likely to lead to no remaining milk by the expiration date.

In summary, the marginal WTP for the presented attributes were higher for women with lower ages and higher household incomes. Families with children under the age of eight were found to place more value on safety-related attributes such as production and remaining shelf life. The fact that consumers with lower ages have a greater willingness to pay for sustainable production methods can be seen as a result reflecting the recent trends in food choices such as food safety and the environment as well as animal welfare.

4.4. Marginal Willingness to Pay for Awareness of Mountainous Dairy Farming

Unlike other attributes, “performing mountainous dairy farming” is not a physical characteristic of milk that can be felt or experienced by consumers through consuming milk. Therefore, this attribute should be informed to consumers via the labeling attached to the package of milk, which suggests that there are consumers who are well acquainted with this information and, at the same time, consumers who do not know or do not care about this. To address this issue in estimating marginal WTP, we classified the consumers by the awareness level for mountainous dairy farming. In other words, a survey question was asked regarding the awareness of mountainous dairy farming. As shown in

Table 7, survey results indicated that consumers who answered “heard of it”, “knows little”, “don’t know”, and “knows well” comprised 45.6%, 38.8%, 12%, and 4.7%, respectively.

The marginal WTP was estimated by dividing the consumers into two groups with low awareness (“don’t know” and “heard of it”) and those with high awareness (“knows little” and “knows well”), as shown in

Table 8. According to the estimation results, the group with high awareness was more willing to pay by

$0.71/L for milk produced via mountainous dairy farming than cage dairy farming, which was

$0.07/L higher than the one from the group with less awareness (

$0.64/L). In other words, the WTP for milk produced through sustainable farming increased as the awareness of it rose. Comparing the marginal WTP for different attributes by awareness level, the WTP for milk type (high-calcium and low–fat) was higher in the group with high awareness than those with low awareness. On the other hand, for brands (Seoul, Maeil, etc.), a group with low awareness tended to pay more than those of high-awareness groups.

This implies that consumers with a high awareness of mountainous dairy farming consider the health aspect of milk and sustainability when purchasing it, while the consumers with low awareness focus more on milk brands. On the presumption that the consumers who have a higher awareness of mountainous dairy farming are the people who have a higher interest in environment and sustainability, this estimation result is very reasonable.

5. Estimation Results of Preference Share

Using the above estimation results, the share of consumer preference by the attribute level of milk can be calculated. In this study, the change of preference share following the change in the specific attribute level was analyzed for several different scenarios. The preference share, which is based on Equation (3) (

), of the 16 alternatives derived from the orthogonal design is calculated as shown in

Table 9. The alternative with the highest preference share is option 3 (high-calcium, mountainous dairy farming, a brand of Maeil, four days of remaining shelf life, and

$1.61/L), and the preference share, in this case, was estimated to be 15.1%. The preference shares of option 15 (regular, mountainous dairy farming, the brand of Seoul, two days of remaining shelf life, and

$1.61/L) and option 5 (regular, mountainous dairy farming, the brand of Namyang, eight days of remaining shelf life, and

$1.79/L) were estimated to be 14.2% and 12%, respectively. On the other hand, the preference share of option 10 (high-calcium, traditional cage dairy farming, Namyang, two days of remaining shelf life, and

$1.97/L) was estimated to be the lowest at 1.1%, and the preference share of option 9 (regular, traditional cage dairy farming, other brands, four days of remaining self life, and

$1.97/L) was estimated to be 1.2%, which also shows relatively low preference share.

Any options with the attribute of traditional cage farming did not yield the preference share which is greater than 5%. And, among eight options where the attribute “mountainous dairy farming” was included, preference share became greater than 10%, except for two cases. This suggests that the property of sustainability would be effective in setting the marketing strategy of milk for expanding market share.

We investigated a hypothetical change in the preference share according to the change of milk type. The change in preference share for the scenarios that allow different milk types is estimated in

Table 10. For this analysis, the baseline (A) was set by assuming that the remaining shelf life and brand were the same. The other attribute levels for this baseline (production method, milk type, and price) were selected and combined so that corresponding preference shares would not be substantially different one from another.

While Scenario 1 changed the attribute from regular milk to high-calcium milk, Scenarios 2 and 3 were based on changing the attribute level from low-fat milk to high-calcium milk. As a result of the scenario analysis, when converting from regular milk to high-calcium milk, as in Scenario 1C, the share of preference rose 6.4% points from 34.2% to 40.6%. Switching from low-fat milk to high-calcium milk, as in Scenarios 2B and Scenario 3D, the share of preference rose by approximately 2.9% to 3.4% points.

Using the same process, the change in the preference share according to the production method is estimated in

Table 11. In the baseline (B), the remaining shelf life and brand were assumed to be the same and other attribute levels for this baseline were selected in such a way that the difference among corresponding preference shares was not big. If we change the production method from traditional cage dairy farming to mountainous dairy farming, as in Scenario 4A, Scenario 5B, and Scenario 6C, the share of preference was expected rise within the range of 24.9% and 30.4% points.

A comparison of the results across

Table 10 and

Table 11 provides important insight. The physical properties of milk, such as low-fat and high-calcium, does matter in increasing market share by appealing to the consumers’ preference. However, changing the production method from cage farming to mountainous farming is much more appealing to the consumers, as confirmed by drastic changes in preference share, as in shown in

Table 11, which are far greater than the changes made in

Table 10. As we can see from the result of estimating marginal willingness to pay, the scenario-based analysis of the preference share shows that consumers’ interests and preferences for sustainability are higher than that of other attributes. This result is expected to be used as basic data to predict changes in consumer consumption trends and preferences in connection with production policies toward sustainability.

6. Conclusions

Consumption of meat and dairy products increases as income rises and urbanization progresses in developing countries, and in response, the production of these products increases. However, the increase in meat and dairy products due to the change in consumption patterns leads to challenges that need to be solved, such as environmental pollution and climate change. On this ground, the need for sustainable farming to effectively utilize natural resources and protect the environment is increasing. While we agree that the necessity and importance of performing sustainable production in terms of preventing environmental pollution and semi-permanent use of natural resources are sufficient, the consumer’s preference and WTP that may cover the cost for performing the sustainable food production still needs to be investigated further.

We analyzed the consumer’s preference and WTP for milk, one of the representative dairy products, by focusing on whether or not it was produced in a sustainable way. The results of the choice experiment indicate that marginal WTP for the aspect of sustainable production is the highest compared to the value of other attributes of milk. Consumers are willing to pay $0.67/L more for the milk produced by mountainous dairy farming than the one by cage dairy farming. It can be seen that the willingness to pay for milk produced by mountainous dairy farming is greater than that of other attributes.

The consumers with a high awareness of sustainability were estimated to be willing to pay $0.71/L for the milk produced by mountainous dairy farming while WTP of the milk in the low-awareness consumers was estimated to be $0.64/L. This shows that consumers’ preference and WTP for sustainable food production is influenced by the pre-existing knowledge, thus informing the importance of sustainability to consumers is worthwhile to be pursued by the government, if the policy is intended to increase the consumption of environmental-friendly food products. The results of preference-share estimations show that the change in consumer preference due to the change from cage dairy farming to sustainable farming is much greater than the one due to the change in physical properties such as fat and calcium.

The consumer’s choice for sustainability identified through the change in marginal WTP and preference share can be attributed to the results perceiving the importance of the environment and long-term economics, along with the needs of consumers who want to consume safe food. Considering that consumers’ awareness of sustainable agriculture is not yet high and that consumer groups with higher awareness are more willing to pay, the consumer’s choice for sustainability may have a greater value than that of the present, and thus the production system will gradually change. However, the current government-supported policies related to livestock production focus on subsidizing production costs from the producer side, not from the consumer side, thus, it is difficult to fill the gap between the production cost of conventional cage breeding and mountainous dairy farming. Therefore, referring to the results of this study, if we raise awareness on sustainable livestock and devise a policy to differentiate livestock products produced in a sustainable way from conventional cage farming, the price of milk produced in a sustainable way can be made higher than the price of milk produced through conventional cage breeding. However, on the other hand, there is a limit to promote sustainable dairy farming since the emphasis placed on the need and importance of sustainable farming cannot unilaterally force producers to engage in less-profitable production. Therefore, the products from sustainable farming must be differentiated through labeling so that consumers can pay a higher price.

This paper confirmed that consumers’ WTP for the milk produced in a sustainable way is substantially high, but whether this WTP is large enough to offset the additional cost for pursuing sustainable production of milk was not investigated. This is a topic that is worthwhile to be analyzed in further research. Nevertheless, the contribution of this study could be evaluated in that an example of the grounds for pursuing sustainable agriculture is identified with the case of milk.