The Drivers of Sustainable Apparel and Sportswear Consumption: A Segmented Kano Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background: Sustainable Clothing and Footwear Consumption

2.1. Drivers of Sustainable Clothing and Footwear Consumption

2.1.1. Drivers in the Pre-Purchase and Purchase Phase

2.1.2. Drivers in the Post-Purchase Phase

2.2. Barriers of Sustainable Clothing and Footwear Consumption and How to Avoid Them

2.2.1. Internal Barriers and Remedies

2.2.2. External Barriers and Remedies

3. Research Design: A Segmented Kano Perspective for the Apparel and Sportswear Industry

3.1. Kano Model and the Segmented Kano Perspective

- Offerings categorized as must-be (M) are assumed to be taken for granted by the customer. Existence does not lead to customer satisfaction, but, in contrast, absence leads to customer dissatisfaction.

- Offerings categorized as one-dimensional (O) is proportional to customer satisfaction: existence leads to customer satisfaction, absence to dissatisfaction.

- Offerings categorized as attractive (A) are assumed to be not expected by customers. Their existence leads to customer satisfaction and, in contrast, their absence does not lead to customer dissatisfaction. The popularity of these offerings is assumed to be rather short-term and thus, they disappear or turn into must-be offerings.

- Offerings categorized as indifferent (I) are assumed not to affect customer satisfaction. Hence, neither their existence nor their absence impacts customer satisfaction or dissatisfaction, respectively.

- The presence of reverse (R) offerings leads to customer dissatisfaction, and their absence leads to customer satisfaction.

- If none of the above categories can be assumed or assessed, the offerings are categorized as questionable (Q).

3.2. Apparel and Sportswear Industry Use Case Selection, Concretization of the Offerings, Questionnaire

3.3. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample of Typical Apparel and Sportswear Consumers

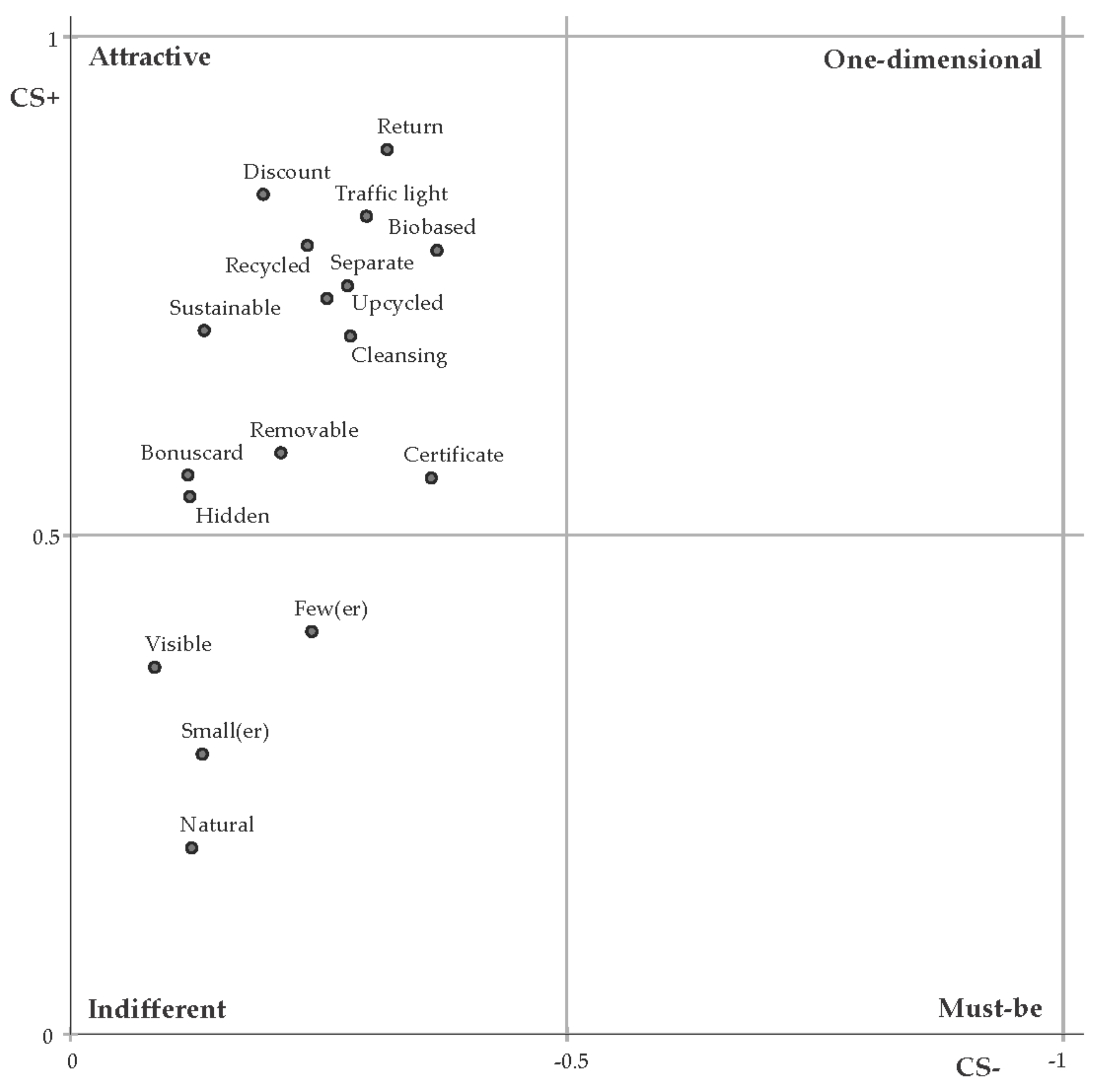

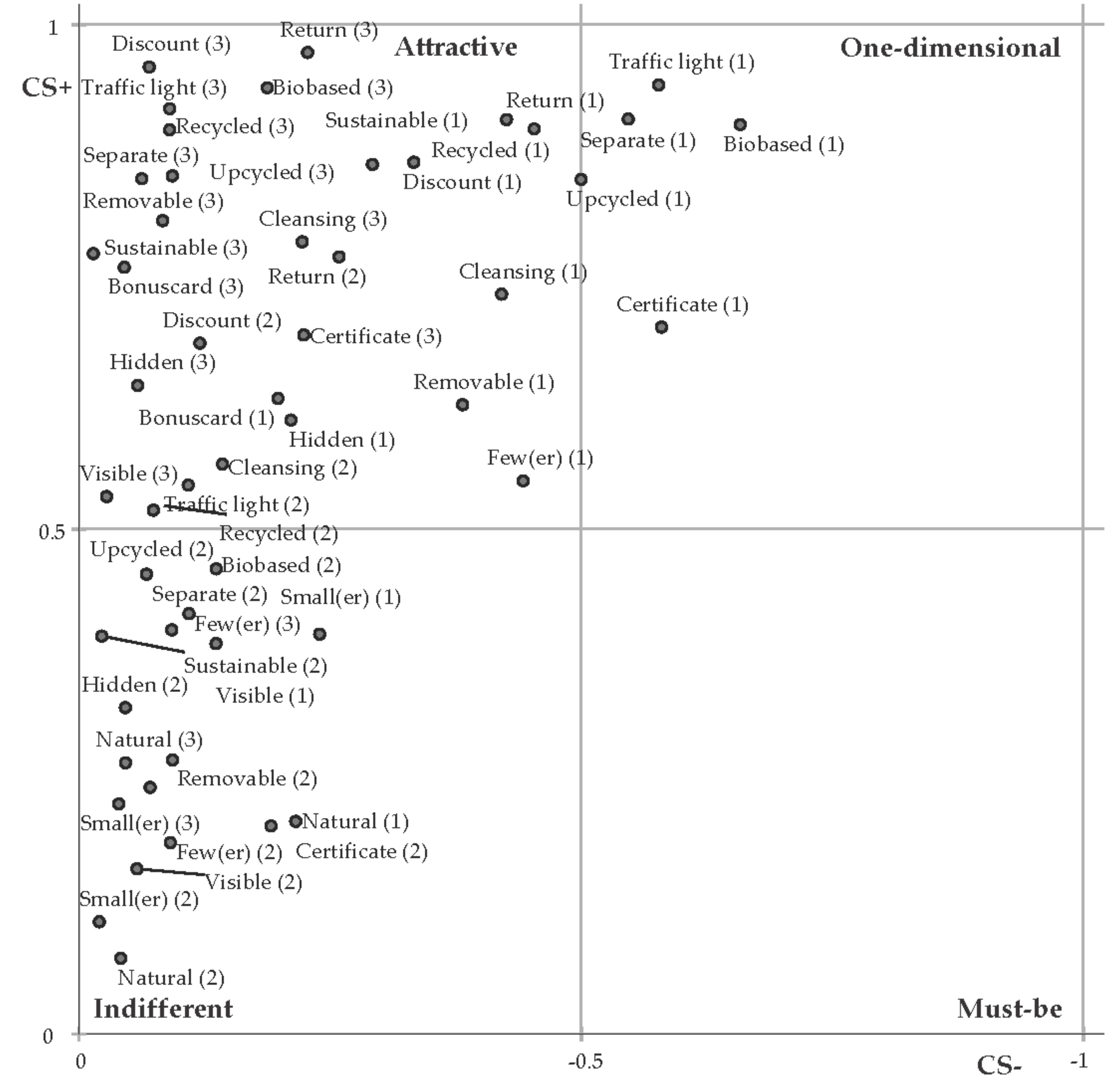

4. Results: A Segmented Kano Perspective for the Apparel and Sportswear Industry

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. The costs and benefits of consuming. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Hassi, L. Emerging design strategies in sustainable production and consumption of textiles and clothing. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1876–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goworek, H.; Fisher, T.; Cooper, T.; Woodward, S.; Hiller, A. The sustainable clothing market: An evaluation of potential strategies for UK retailers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 935–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, L.; Lea-Greenwood, G. Fast fashion in the retail store environment. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2010, 38, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achabou, M.A.; Dekhili, S. Luxury and sustainable development: Is there a match? J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagurney, A.; Yu, M. Sustainable fashion supply chain management under oligopolistic competition and brand differentiation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goworek, H.; Oxborrow, L.; Claxton, S.; McLaren, A.; Cooper, T.; Hill, H. Managing sustainability in the fashion business: Challenges in product development for clothing longevity in the UK. J. Bus. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Trudel, R. The effect of recycling versus trashing on consumption: Theory and experimental evidence. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R.; Argo, J.J.; Meng, M.D. The recycled self: Consumers’ disposal decisions of identity-linked products. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Patrick, V.M. Getting consumers to recycle NOW! When and why cuteness appeals influence prosocial and sustainable behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 2017, 36, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Nenkov, G.Y.; Gonzales, G.E. Knowing what It makes: How product transformation salience increases recycling. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, A.K.; Naderer, G. Quantitative and qualitative insights into consumers’ sustainable purchasing behaviour: A segmentation approach based on motives and heuristic cues. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Boks, C. Sustainable clothing design: Use matters. J. Des. Res. 2012, 10, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Consumer clothing disposal behaviour: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K. Consumers’ clothing disposal behavior—A synthesis of research results. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldini, I.; Stappers, P.J.; Gimeno-Martinez, J.C.; Daanen, H.A.M. Assessing the impact of design strategies on clothing lifetimes, usage and volumes: The case of product personalisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1414–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, B.; Sandin, G.; Peters, G.M. Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: Can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, R.; Cotte, J. Does it pay to be good? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2009, 50, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, P.; Devinney, T.M. Do what consumers say matter? The misalignment of preferences with unconstrained ethical intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 76, 361–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughner, R.S.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A.; Shultz, C.J.; Stanton, J. Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S. Attractive quality and must-be quality. J. Jpn. Soc. Qual. Control 1984, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, D.; Rese, A.; Röglinger, M. Conversational user interfaces for online shops: A Segmented Kano perspective. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, D.; Rese, A. How to increase multichannel shopping satisfaction? A Segmented Kano perspective for the selection of new technologies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020. (In Press)

- Rese, A.; Schlee, T.; Baier, D. The need for services and technologies in physical fast fashion stores: Generation Y’s opinion. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 1437–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Stoney Creek, CT, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Joergens, C. Ethical fashion: Myth or future trend? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2006, 10, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundblad, L.; Davies, I.A. The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J. Consum. Behav. 2016, 15, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gam, H.J. Are fashion-conscious consumers more likely to adopt eco-friendly clothing? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2011, 15, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller Connell, K.Y. Internal and external barriers to eco-conscious apparel acquisition. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 34, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Eco-clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.; Moore, R. Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wang, Y.; Lo, C.K.Y.; Shum, M. The impact of ethical fashion on consumer purchase behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Lamb, P.; Peretiatko, R. Green decisions: Demographics and consumer understanding of environmental labels. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C.; Dong, H.; Lee, Y.-A. Factors influencing consumers’ purchase intention of green sportswear. Fash. Text. 2017, 4, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustvedt, G.; Dickson, M.A. Consumer likelihood of purchasing organic cotton apparel. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2009, 13, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pookulangara, S.; Shephard, A. Slow fashion movement: Understanding consumer perceptions—An exploratory study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Boks, C.; Klepp, I.G. Potential for environmental improvements in laundering. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Berning, C.K.; Dietvorst, T.F. What about disposition? J. Mark. 1977, 41, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Sell, give away, or donate: An exploratory study of fashion clothing disposal behaviour in two countries. Int. Rev. Retail. Consum. Res. 2010, 20, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtwistle, G.; Moore, C.M. Fashion clothing—Where does it all end up? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M.; Laursen, S.E.; Russell, S.N.; de Rodríguez, C.M.; Bocken, N.M.P. An approach to scenario analysis of the sustainability of an industrial sector applied to clothing and textiles in the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimäki, K.; Lang, C.; Kujala, S. A Use-Oriented Clothing Economy? Preliminary affirmation for sustainable clothing consumption alternatives. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirscher, A.-L.; Niinimäki, K.; Joyner Armstrong, C.M. Social manufacturing in the fashion sector: New value creation through alternative design strategies? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4544–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, S.; Lee, K.H. How social capital impacts the purchase intention of sustainable fashion products. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G.; Boks, C. Changing laundry habits in Norway. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Armstrong, C.M.; Brannon, L.A. Drivers of clothing disposal in the US: An exploration of the role of personal attributes and behaviours in frequent disposal. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddi, S.; Yan, R.-N.; Bloodhart, B.; Bajtelsmit, V.; McShane, K. Exploring young adult consumers’ sustainable clothing consumption intention-behavior gap: A Behavioral Reasoning Theory perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.-H.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.-J.; Wang, Y.-F. Sustainable rent-based closed-loop supply chain for fashion products. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7063–7088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Oskamp, S. Managing scarce environmental resources. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Stokols, D., Altman, I., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 1044–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude-behavior relationships. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, J.L.; Malkus, A.J. Adolescent environmental behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schahn, J.; Holzer, E. Studies of individual environmental concern. Environ. Behav. 1990, 22, 767–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, F.; Roby, H.; Dibb, S. Sustainable clothing: Challenges, barriers and interventions for encouraging more sustainable consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Damhorst, M.L. Environmental concern and apparel consumption. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1998, 16, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Lee, H.-H. Young Generation Y consumers’ perceptions of sustainability in the apparel industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Hogg, G.; Wilson, E.; Shiu, E.; Hassan, L. Fashion victim: The impact of fair trade concerns on clothing choice. J. Strat. Mark. 2006, 14, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanow, H.; McEachern, M.G.; Jeffrey, A. The influence of ethical trading policies on consumer apparel purchase decisions. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2005, 33, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bly, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Reisch, L.A. Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S. Environmentalism and consumers’ clothing disposal patterns: An exploratory study. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1995, 13, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Ko, E. Perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward sustainable fashion: Application of Q and Q-R methodologies. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.E. Contextual effects on environmental attitudes and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S. Do We Know what we need to know? Objective and subjective knowledge effects on pro-ecological behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Geiger, S.M.; Schrader, U. Collaborative fashion consumption—A cross-cultural study between Tehran and Berlin. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, M. Collaborative consumption practices in Southeast Asian cities: Prospects for growth and sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Mooradian, T.A. Sex, personality, and sustainable consumer behaviour: Elucidating the gender effect. J. Consum. Policy 2012, 35, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Ma, J.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisler, A.D.; Eisler, H. Subjective time scaling: Influence of age, gender, and type A and type B behavior. Chronobiologia 1994, 21, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.A.; Holden, S.J.S. Understanding the determinants of environmentally conscious behavior. Psychol. Mark. 1999, 16, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J.; Freudenburg, W.R. Gender and environmental risk concerns. A review and analysis of available research. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 302–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, N.D. The branding of ethical fashion and the consumer: A luxury niche or mass-market Reality? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for Advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Öberg, C.; Sandström, C. How sustainable is the sharing economy? On the sustainability connotations of sharing economy platforms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingaldi, M.; Ulewicz, R. How to make e-commerce more successful by use of Kano’s model to assess customer satisfaction in terms of sustainable development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzler, K.; Hinterhuber, H.H.; Bailom, F.; Sauerwein, E. How to delight your customers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 1996, 5, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulić, J.; Prebežac, D. Which products and services can be used to obtain a high level of customer satisfaction. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2011, 21, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson-Witell, L.; Fundin, A. Dynamics of service attributes: A test of Kano’s theory of attractive quality. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2005, 16, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, J.R.; Clausing, D. The House of Quality. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1988, 66, 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, C.; Blauth, R.; Boger, D.; Bolster, C.; Burchill, G.; DuMouchel, W.; Pouliot, F.; Richter, R.; Rubinoff, A.; Shen, D.; et al. Kano’s methods for understanding customer-defined quality. Cent. Qual. Manag. J. 1993, 2, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, A.; Zairi, M. Kano model: A dynamic approach for classifying and prioritising requirements of airline travellers with three case studies on international airlines. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2009, 20, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Pourhamidi, M.; Antony, J.; Hyun Park, S. Typology of Kano models: A critical review of literature and proposition of a revised model. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2013, 30, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.; Fang, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Jeris, C. A robust and scalable clustering algorithm for mixed type attributes in large database environment. In Proceedings of the Seventh ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–29 August 2001; pp. 263–268. [Google Scholar]

| Dysfunctional Question | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Like | (2) Must be | (3) Neutral | (4) Live with | (5) Dislike | ||

| Functional question | (1) Like | Q | A | A | A | O |

| (2) Must be | R | I | I | I | M | |

| (3) Neutral | R | I | I | I | M | |

| (4) Live with | R | I | I | I | M | |

| (5) Dislike | R | R | R | R | Q | |

| Aspect | Offering | Detailed Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Sustainable | Only sustainable products are offered. | [30,67] |

| Natural | Only products in natural colors are offered. | [30] | |

| Separate | A separate section with sustainable products is offered. | [30,67] | |

| Small(er) | A small(er) range is offered (e.g., 1000 instead of 3000 sneakers). | [32] | |

| Few(er) | Few(er) fashion cycles are launched (e.g., a specific collection is sold for two months instead of two weeks). | [32] | |

| Labeling | Traffic light | Products are classified with a traffic light to indicate the sustainability level (e.g., red: minimum, yellow: re/upcycled, green: biobased). | [32,36,59] |

| Removable | Products are tagged with a removable seal to indicate a high sustainability level. | [32,36,59] | |

| Hidden | Products are tagged with a hidden seal to indicate a high sustainability level (e.g., on the sneaker sole). | [32,36,59] | |

| Visible | Products are tagged with a visible seal to indicate a high sustainability level. | [32,36,59] | |

| Certificate | Products are officially certified by an ecolabel to indicate a high sustainability level (e.g., Blauer Engel, Organic Textile, Fair Trade). | [32,36,59] | |

| Processes | Return | A discount on the purchase of the next sustainable product is offered when products are returned to be recycled. | [32,38,46,76] |

| Discount | A discount on the purchase of the next sustainable product is offered when a sustainable product is bought. | [32,38,46,76] | |

| Bonus card | Bonus points are collected when buying products. The more sustainable, the more points. Points can be redeemed when buying sustainnable products. Further, when reaching a minimum number of points, customers get early access to new sustainable products. | [32,38,46,76] | |

| Materials | Upcycled | Products are made of upcycled materials (e.g., ocean plastic). | [42,45] |

| Biobased | Products are made of biobased and -degradable materials (e.g., biosteel). | [42,45] | |

| Recycled | Products are made of components derived from returned products. | [42,45] | |

| Cleaning | A repair and/or cleaning service is offered to prolong the product life cycle. | [2,15] |

| Demographics | Specification | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–24 | 54.49% |

| 25–34 | 39.59% | |

| 35–64 | 5.92% | |

| Gender | Female | 56.53% |

| Male | 43.27% | |

| Employment status | Students | 77.35% |

| Employed | 14.49% | |

| Freelancer | 2.65% | |

| Other | 5.51% |

| Offering | Overall Category Frequencies (n = 490) | TS | CS+ | CS− | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #A | #I | #M | #O | #Q | #R | |||||

| Range | Sustainable | 286 | 125 | 15 | 49 | 1 | 14 | 64 | 0.7053 | −0.1347 |

| Natural | 62 | 305 | 35 | 16 | 9 | 63 | 26 | 0.1866 | −0.1220 | |

| Separate | 249 | 100 | 21 | 114 | 1 | 5 | 58% | 0.7500 | −0.2789 | |

| Small(er) | 83 | 257 | 25 | 27 | 2 | 96 | 26% | 0.2806 | −0.1327 | |

| Few(er) | 104 | 245 | 30 | 82 | 2 | 27 | 33% | 0.4035 | −0.2430 | |

| Labeling | Traffic light | 263 | 76 | 11 | 133 | 2 | 5 | 57% | 0.8199 | −0.2981 |

| Removable | 202 | 170 | 27 | 73 | 2 | 16 | 50% | 0.5826 | −0.2119 | |

| Hidden | 205 | 205 | 10 | 46 | 2 | 22 | 45% | 0.5386 | −0.1202 | |

| Visible | 115 | 241 | 5 | 28 | 1 | 100 | 25% | 0.3676 | −0.0848 | |

| Certificate | 159 | 146 | 66 | 108 | 1 | 10 | 53% | 0.5574 | −0.3633 | |

| Processes | Return | 285 | 46 | 9 | 146 | 2 | 2 | 61% | 0.8868 | −0.3189 |

| Discount | 313 | 69 | 6 | 86 | 2 | 14 | 66% | 0.8418 | −0.1941 | |

| Bonuscard | 207 | 196 | 5 | 49 | 1 | 32 | 44% | 0.5602 | −0.1182 | |

| Materials | Upcycled | 245 | 108 | 17 | 106 | 2 | 12 | 57% | 0.7374 | −0.2584 |

| Biobased | 228 | 78 | 26 | 153 | 2 | 3 | 55% | 0.7856 | −0.3691 | |

| Recycled | 283 | 84 | 17 | 98 | 3 | 5 | 64% | 0.7905 | −0.2386 | |

| Cleansing | 224 | 125 | 21 | 116 | 2 | 2 | 53% | 0.6996 | −0.2819 | |

| Offering | Segment-Specific Category Frequencies (Segment 1: n = 203 / Segment 2: n = 142 / Segment 3: n = 145) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #A | #I | #M | #O | #Q | #R | ||

| Range | Sustainable *** | 126 / 51 / 109 | 17 / 78 / 30 | 11 / 2 / 2 | 48 / 1 / 0 | 0 / 1 / 0 | 1 / 9 / 4 |

| Natural *** | 29 / 6 / 27 | 120 / 109 / 76 | 30 / 2 / 3 | 11 / 3 / 2 | 3 / 6 / 0 | 10 / 16 / 37 | |

| Separate *** | 87 / 49 / 113 | 5 / 73 / 22 | 14 / 7 / 0 | 97 / 8 / 9 | 0 / 1 / 0 | 0 / 4 / 1 | |

| Small(er) *** | 51 / 10 / 22 | 95 / 87 / 75 | 21 / 1 / 3 | 25 / 1 / 1 | 0 / 2 / 0 | 11 / 41 / 44 | |

| Few(er) *** | 47 / 16 / 41 | 64 / 104 / 77 | 26 / 3 / 1 | 62 / 9 / 11 | 1 / 1 / 0 | 3 / 3 / 1 | |

| Labeling | Traffic light *** | 79 / 63 / 121 | 6 / 60 / 10 | 6 / 3 / 2 | 110 / 12 / 11 | 1 / 1 / 0 | 1 / 3 / 1 |

| Removable *** | 66 / 27 / 109 | 57 / 90 / 23 | 18 / 4 / 5 | 58 / 8 / 7 | 0 / 2 / 0 | 4 / 11 / 1 | |

| Hidden *** | 86 / 39 / 80 | 71 / 85 / 49 | 7 / 3 / 0 | 35 / 3 / 8 | 0 / 2 / 0 | 4 / 10 / 8 | |

| Visible *** | 47 / 13 / 55 | 105 / 85 / 51 | 3 / 2 / 0 | 21 / 4 / 3 | 0 / 1 / 0 | 27 / 37 / 36 | |

| Certificate *** | 57 / 21 / 81 | 27 / 89 / 30 | 33 / 19 / 14 | 83 / 7 / 18 | 0 / 1 / 0 | 3 / 5 / 2 | |

| Processes | Return *** | 102 / 75 / 108 | 14 / 28 / 4 | 5 / 4 / 0 | 81 / 32 / 33 | 0 / 2 / 0 | 1 / 1 / 0 |

| Sustainable *** | 109 / 77 / 127 | 23 / 40 / 6 | 4 / 2 / 0 | 62 / 14 / 10 | 0 / 2 / 0 | 5 / 7 / 2 | |

| Bonuscard *** | 87 / 25 / 95 | 71 / 93 / 32 | 2 / 3 / 0 | 37 / 6 / 6 | 0 / 1 / 0 | 6 / 14 / 12 | |

| Materials | Upcycled *** | 86 / 52 / 107 | 15 / 73 / 20 | 16 / 0 / 1 | 85 / 9 / 12 | 0 / 2 / 0 | 1 / 6 / 5 |

| Biobased *** | 64 / 50 / 114 | 5 / 70 / 3 | 15 / 5 / 6 | 118 / 14 / 21 | 0 / 2 / 0 | 1 / 1 / 1 | |

| Recycled *** | 102 / 62 / 119 | 9 / 63 / 12 | 12 / 2 / 3 | 80 / 8 / 10 | 0 / 3 / 0 | 0 / 4 / 1 | |

| Cleansing *** | 78 / 65 / 81 | 39 / 63 / 12 | 15 / 2 / 3 | 70 / 8 / 10 | 1 / 3 / 0 | 0 / 4 / 1 | |

| Aspect | Specifications | Overall | Segment 1 | Segment 2 | Segment 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–24 | 54.5% | 56.6% | 53.5% | 52.5% |

| 25–34 | 39.6% | 34.4% | 45.1% | 41.4% | |

| 35–64 | 5.92% | 9.0% | 1.4% | 6.1% | |

| Gender *** | Female | 56.5% | 65.5% | 46.5% | 46.2% |

| Male | 43.3% | 34.5% | 52.8% | 53.8% | |

| Employment status | Students | 77.4% | 72.0% | 83.8% | 78.6% |

| Employed | 14.5% | 16.3% | 11.3% | 15.2% | |

| Freelancer | 2.7% | 5.4% | 0.0% | 1.4% | |

| Other | 5.5% | 6.3% | 5.9% | 14.8% | |

| Sneakers bought per year | <1 | 8.4% | 11.8% | 7.7% | 4.1% |

| 1 | 34.1% | 36.0% | 31.7% | 33.6% | |

| 2–3 | 41.8% | 38.4% | 44.4% | 44.1% | |

| >3 | 9.4% | 13.8% | 16.2% | 18.2% | |

| Sustainable consumption attitude in general | I’m informed *** | 3.17 (0.911) | 3.35 (0.833) | 2.89 (0.939) | 3.21 (0.927) |

| Important for me *** | 3.45 (0.954) | 3.81 (0.876) | 3.01 (0.956) | 3.39 (0.859) | |

| I would pay more *** | 3.69 (1.008) | 4.07 (0.847) | 3.15 (1.106) | 3.68 (0.872) | |

| Labels are helpful *** | 4.40 (0.908) | 4.74 (0.559) | 3.79 (1.166) | 4.52 (0.698) | |

| Sneakers buying motives | I buy when needed | 3.48 (1.297) | 3.48 (1.291) | 3.57 (1.318) | 3.37 (1.289) |

| I buy when inspired | 3.25 (1.321) | 3.16 (1.316) | 3.25 (1.274) | 3.36 (1.372) | |

| Importance when buying sneakers | Price ** | 4.26 (1.214) | 4.43 (1.130) | 4.20 (1.216) | 4.08 (1.299) |

| Quality | 4.99 (0.942) | 5.06 (0.960) | 4.91 (0.929) | 4.97 (0.928) | |

| Appearance | 5.63 (0.701) | 5.59 (0.714) | 5.58 (0.707) | 5.73 (0.669) | |

| Brand *** | 3.95 (1.478) | 3.66 (1.538) | 4.18 (1.462) | 4.14 (1.342) | |

| Sustainability *** | 3.14 (1.295) | 3.46 (1.290) | 2.80 (1.297) | 3.02 (1.199) | |

| Comfort | 5.16 (0.951) | 5.26 (0.915) | 5.06 (0.921) | 5.12 (1.020) | |

| Longevity *** | 4.35 (1.213) | 4.46 (1.213) | 4.07 (1.224) | 4.47 (1.173) | |

| Willingness to pay for sustainable sneakers compared to conventional ones for € 100.00 *** | € 116.53 (€15.32) | € 120.61 (€ 14.52) | € 110.66 (€ 16.30) | € 116.58 (€ 13.57) | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baier, D.; Rausch, T.M.; Wagner, T.F. The Drivers of Sustainable Apparel and Sportswear Consumption: A Segmented Kano Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072788

Baier D, Rausch TM, Wagner TF. The Drivers of Sustainable Apparel and Sportswear Consumption: A Segmented Kano Perspective. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072788

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaier, Daniel, Theresa Maria Rausch, and Timm F. Wagner. 2020. "The Drivers of Sustainable Apparel and Sportswear Consumption: A Segmented Kano Perspective" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072788

APA StyleBaier, D., Rausch, T. M., & Wagner, T. F. (2020). The Drivers of Sustainable Apparel and Sportswear Consumption: A Segmented Kano Perspective. Sustainability, 12(7), 2788. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072788