The Contours of State Retreat from Collaborative Environmental Governance under Austerity

Abstract

1. Introduction

“How has collaborative environmental governance been effected by state retreat under austerity?”

Conceptualising the Impact of Austerity

2. Materials and Methods

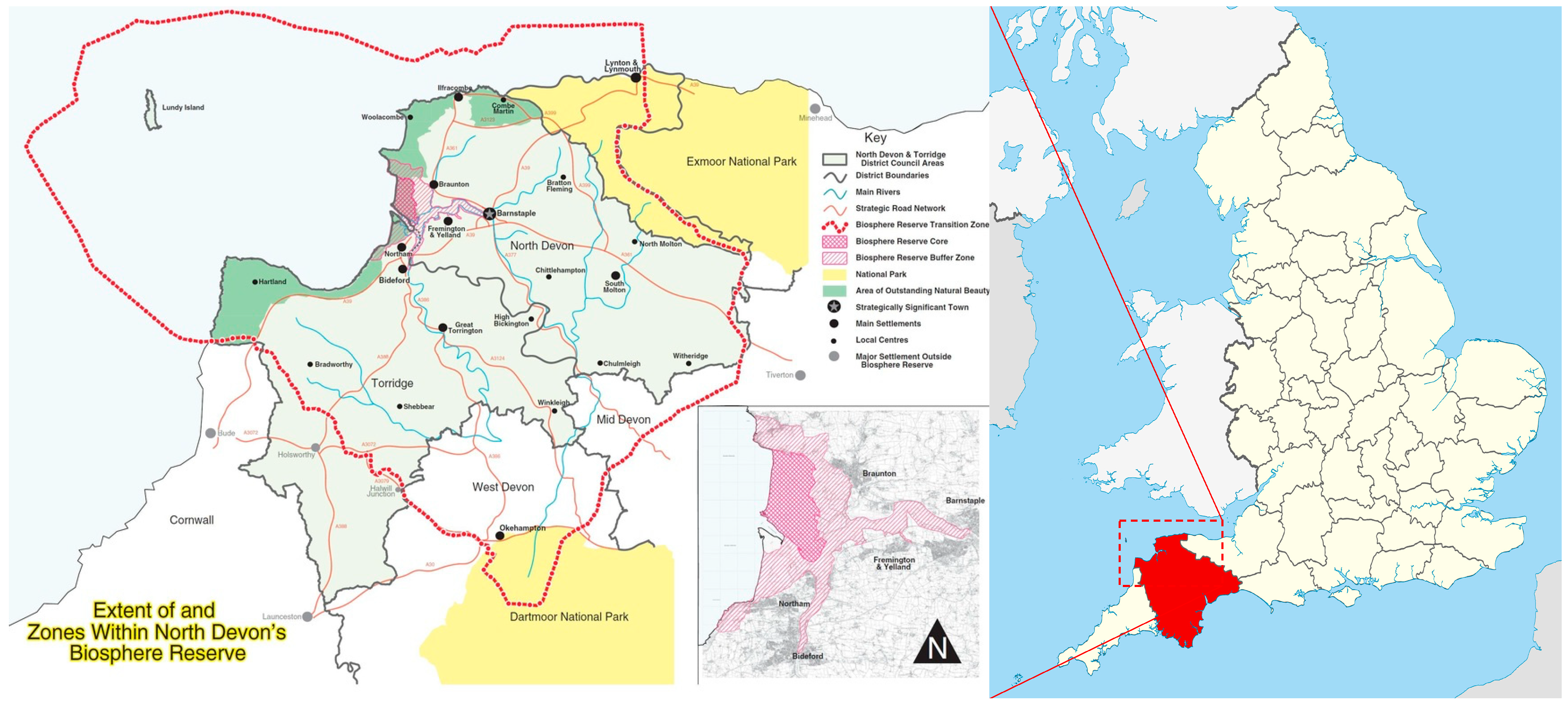

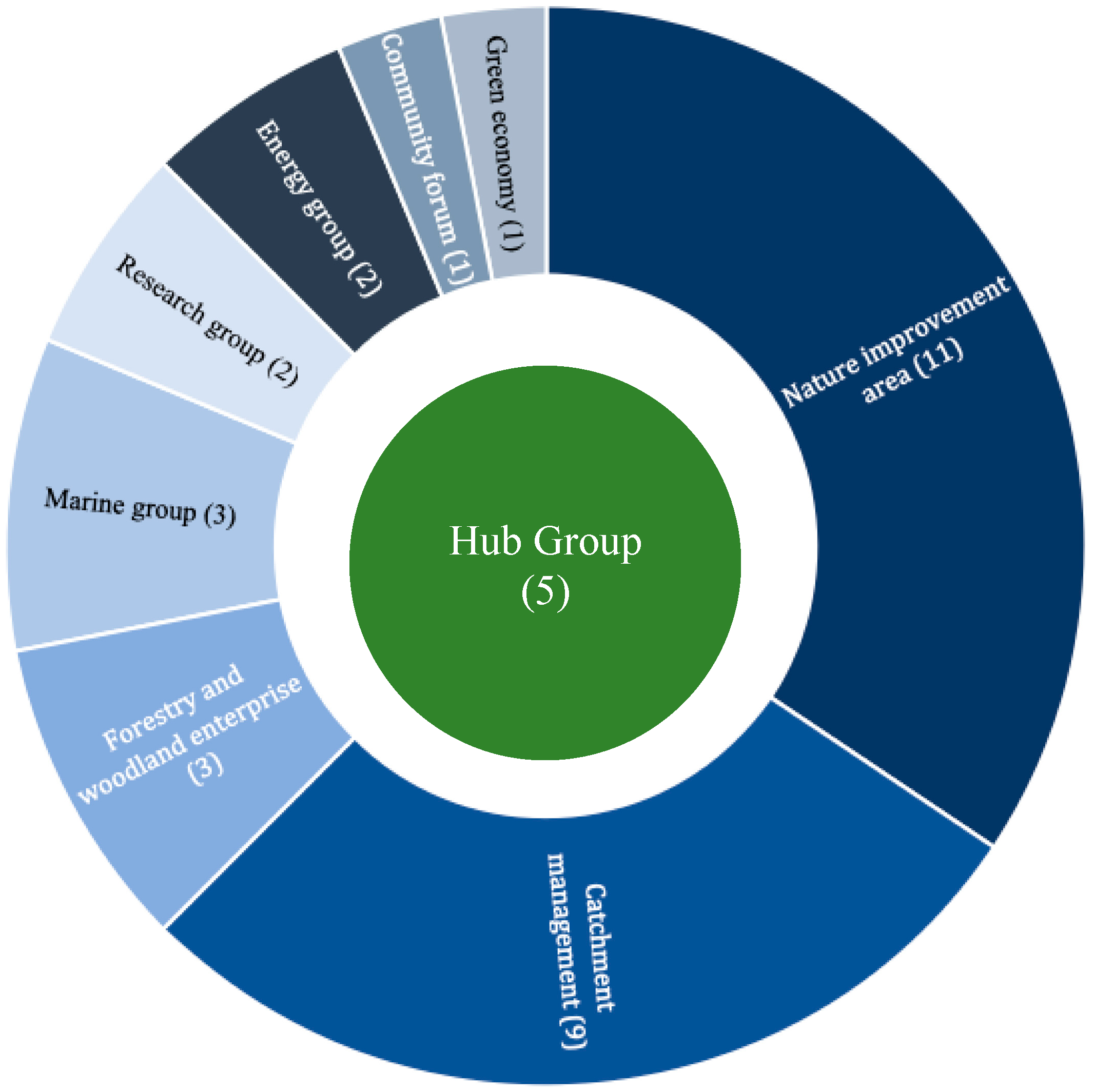

Case Selection and Description

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Austerity

3.2. Funding

“well… once we could count on getting X every year, but now we only really get Y or less than that”.

“funding always reflected Defra priorities, we’ve just noticed that this has become more of a thing, with fewer opportunities for us to have a say”.

“so much of the policy we see now, such as the natural capital approach we’ve already discussed, are led by political interests”.

“as Defra get cut, so do we, and that all rolls downhill to the projects we used to support”.

“if management decisions in the biosphere are going to continue to try and represent all the people that live here then we need to keep being at the heart of this”.

“we’re never going to get to real sustainability unless some public funds are put up”.

“There are impacts – XXXXX and his team can’t keep doing what they do … with funding continually reducing year on year”.

“Torridge district council kept trying to offer support where they could, even when they were being cut back to the bone themselves”.

3.3. Governance Structure

“I don’t really spend much biosphere time doing project work anymore …. it’s pretty much all taken up with responding to funding calls and the like”.

3.4. Relationships

“we aren’t really as close as pre-2010. Once they (unnamed organisation) came to meetings, they contributed, now it’s different”.

“no one wants to stop attending the biosphere reserve meetings or spending less energy on the nitty gritty of working in north Devon, but the drum beat for doing more with less is remorseless”.

“Every new funding call seems to go further and further away from what we want to do, and what we know is right for here”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Collaborative Governance

4.2. State Retreat

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Ident. | Field | Sector | Grade | Org. Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Ecology | Independent | Senior | na |

| P2 | Planning | Public | Middle | Large |

| P3 | Ecology | Voluntary | Middle | Micro |

| P4 | Farming | Voluntary | Middle | Micro |

| P5 | Planning | Public | Senior | Large |

| P6 | Ecology | Voluntary | Middle | Micro |

| P7 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Medium |

| P8 | Landscape/heritage | Independent | Senior | na |

| P9 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Micro |

| P10 | Ecology | Public | Middle | Small |

| P11 | Ecology | Public | Senior | Medium |

| P12 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Micro |

| P13 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Medium |

| P14 | Ecology | Public | Middle | Large |

| P15 | Landscape/heritage | Voluntary | Middle | Micro Micro |

| P16 | Landscape/heritage | Voluntary | Senior | Micro |

| P17 | Arts | Voluntary | Middle | Micro |

| P18 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Medium |

| P19 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Micro |

| P20 | Landscape/heritage | Voluntary | Middle | Large |

| P21 | Government | Voluntary | Senior | Micro |

| P22 | Government | Voluntary | Junior | Micro |

| P23 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Micro |

| P24 | Planning | Voluntary | Senior | Small |

| P25 | Landscape/heritage | Voluntary | Middle | Large |

| P26 | Marine | Voluntary | Senior | Micro |

| P27 | Marine | Public | Senior | Medium |

| P28 | Ecology | Public | Middle | Medium |

| P29 | Landscape/heritage | Voluntary | Senior | Large |

| P30 | Planning | Public | Senior | Large |

| P31 | Ecology | Voluntary | Middle | Large |

| P32 | Ecology | Voluntary | Senior | Medium |

References

- Gribel, T.; Sturm, R.; Winklemann, T. Austerity: A Journey to Unknown Territory: Discourses, Economics and Politics, 1st ed.; Nomos: Baded-Baden, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McGahey, R. The political economy of austerity in the United States. Soc. Res. 2013, 80, 717–748. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K.; O’Boyle, B. Austerity Ireland: The Failure of Irish Capitalism, 1st ed.; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pavolini, E.; Margarita, L.; Guillen, A.-M.; Ascoli, U. From austerity to permanent strain? The EU and welfare state reform in Italy and Spain. Comp. Eur. Polit. 2015, 13, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M. The politics of austerity: A recent history. In The Politics of Austerity, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fourton, C. Political and discursive characteristics of the austerity consensus in the UK and in France since 1975. Obs. Soc. B. 2017, 19, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.; Henderson, T. The Consequences of Fiscal Austerity on Western Australia; Centre for Future Work at the Australia Institute: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schwiter, K.; Berndt, C.; Truong, J. Neoliberal austerity and the marketisation of elderly care. Social Cult. Geogr. 2018, 19, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, E.; Penn, H. Childcare markets in an age of austerity. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2014, 22, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, R.; Spencer, J. Understanding the marketisation of the probation service through an interpretative policy framework. In The Management of Change in Criminal Justice; Wasik, M., Santatzoglou, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Goobey, P.; Stoker, G. The coalition programme: A new vision for britain or politics as usual? Polit. Q. 2011, 82, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramall, R. The Cultural Politics of Austerity: Past and Present in Austere Times, 1st ed.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, C. Austerity Politics and UK Economic Policy; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dowler, E.; Lambie-Mumford, H. How can households eat in austerity? Challenges for social policy in the UK. Soc. Policy Soc. 2015, 14, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loopstra, R.; Reeves, A.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Barr, B.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Austerity, sanctions, and the rise of food banks in the UK. Br. Med. J. 2015, 350, h1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Halsall, J.P. Living in the age of austerity and migration: The complexities of elderly health and care. Illn. Crisis Loss 2017, 25, 340–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.; Donovan, C.; Merchant, J. Distancing and limited resourcefulness: Third sector service provision under austerity localism in the north east of England. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russel, D.; Benson, D. Green budgeting in an age of austerity: A transatlantic comparative perspective. Environ. Polit. 2014, 23, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, P.; Burns, C. Measuring the impact of austerity on European environmental policy. In Proceedings of the Paper presented at the Political Studies Association Conference, Sheffield, UK, 30 March–1 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, B.G. Governance as political theory. In Oxford Handbook of Governance, 1st ed.; Levi-Fleur, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A. The governance of sustainable development: Taking stock and looking forwards. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Sp. 2008, 26, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.A.W. The Theory and Practice of Governance: The Next Steps. 2016. Available online: http://www.raw-rhodes.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/TheoryPractice-Governancedocx.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2019).

- Keping, Y. Governance and good governance: A new framework for political analysis. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Steurer, R. Multi-level governance of climate change adaptation through regional partnerships in Canada and England. Geoforum 2014, 51, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobao, L.; Gray, M.; Cox, K.; Kitson, M. The shrinking state? Understanding the assault on the public sector. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Uyl, R.; Russel, D. Climate adaptation in fragmented governance settings: The consequences of reform in public administration. Environ. Polit. 2017, 27, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; de Loë, R.; Plummer, R. Environmental governance and its implications for conservation practice. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Mol, A.P.J. Participation and environmental governance: Consensus, ambivalence and debate. Environ. Values 2003, 12, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, M.; Tin, N.; Lockwood, M.; Sinnasone, S.; Phommasane, S. Collaborative governance of protected areas: Success factors and prospects for hin nam no national protected area, central Laos. Conserv. Soc. 2017, 15, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macura, B.; Secco, L.; Pullin, A.S. What evidence exists on the impact of governance type on the conservation effectiveness of forest protected areas? Knowledge base and evidence gaps. Environ. Evid. 2015, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavola, J. Protected areas governance and justice: Theory and the european union’s habitats directive. Environ. Sci. 2004, 1, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lockwood, M. Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K. Creating public value through collaborative environmental governance. Adm. Publica 2010, 18, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Manzor Rashid, A.Z.M.; Craig, D.; Mukul, S.A.; Khan, N.A. A journey towards shared governance: Status and prospects for collaborative management in the protected areas of Bangladesh. J. For. Res. 2013, 24, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koontz, T.M.; Steelman, T.A.; Carmin, J.; Korfmacher, K.S.; Mosely, C.; Thomas, C. Collaborative Environmental Management: What Roles for Government? 1st ed.; Earthscan: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Headlam, N.; Hepburn, P. ‘The old is dying and the new cannot be born, in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.’ how can local government survive this interregnum and meet the challenge of devolution? Representation 2015, 51, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, J. Between coercion and consent: The politics of “Cooperative Governance” at a time of “Austerity Localism” in London. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 1352–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, V.; Gazzola, P.; Wood, G. The effects of recent austerity on environmental protection decisions: Evidence and perspectives from Scotland. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2019, 30, 1218–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R. The Green State: Rethinking Democracy and Soveringty; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Backstrand, K.; Kronsell, A. Rethinking the Green State: Environmental Governance Towards Climate and Sustainability Transitions; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duit, A. State and Environment: The Comparative Study If Environmental Governance; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Armondi, S. State rescaling and new metropolitan space in the age of austerity. Evidence from Italy. Geoforum 2017, 81, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Barford, A. The depths of the cuts: The uneven geography of local government austerity. Cam. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 541–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.S.; Blanco, I.M. Austerity urbanism: Patterns of neo-liberalisation and resistance in six cities of Spain and the UK. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Sp. 2017, 49, 1517–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.W.; Strange, S. The retreat of the state: The diffusion of power in the world economy. Int. J. 1997, 52, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, S. The Retreat of the State: The Diffusion of Power in the World Economy, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, S.; Kippin, H. Public services after austerity: Zombies, suez or collaboration? Polit. Q. 2017, 88, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headlam, N.; Rowe, M. The end of the affair: Abusive partnerships in austerity. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2013, 7, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chorianopoulos, I.; Tselepi, N. Austerity urbanism: Rescaling and collaborative governance policies in Athens. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2019, 26, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsop-Taylor, N. Surviving tough times: An investigation into environmental voluntary sector organisations under austerity. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2019, 10, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, G. The Transformation of the State: Beyond the Myth of Retreat, 2nd ed.; Red Globe Press: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Humphris, R. Mutating faces of the state? Austerity, migration and faith-based volunteers in a UK downscaled urban context. Sociol. Rev. 2018, 67, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.; Hopwood, N. A practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods: Applied Social Research and Methods Series, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Price, M.F. The world network of biosphere reserves: A flexible structure for understanding and responding to global change. Adv. Glob. Chang. Res. 2003, 9, 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer, K.; Witkowski, E.; Erasmus, B. Reviewing biosphere reserves globally: Effective conservation action or bureaucratic label? Biol. Rev. Cam. Philos. Soc. 2014, 89, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vester, H.F.M.; Lawrence, D.; Eastman, J.R.; Turner, B.L., II; Calme, S.; Dickson, R.; Pozo, C.; Sangermano, F. Land change in the southern yucatán and calakmul biosphere reserve: Effects on habitat and biodiversity. Ecol Appl. 2007, 17, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEldowney, J. Delivering Public Services in the United Kingdom in a Period of Austerity. In Public and Social Services in Europe from Public and Municipal to Private Sector Provision, 1st ed.; Wollmann, H., Kopric, I., Gerard, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bassel, L.; Emejulu, A. Solidarity under austerity: Intersectionality in France and the United Kingdom. Polit. Gend. 2014, 10, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- North Devon UNESCO biosphere reserve. 2016. Available online: http://www.unesco-mab.org.uk/north-devon-biosphere-reserve.html (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Voß, J.P.; Kemp, R. Sustainability and reflexive governance. In Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Voß, J.P., Bauknecht, D., Kemp, R., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Pickering, J. Deliberation as a catalyst for reflexive environmental governance. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, M. The art of survival: Community-based arts organisations in times of austerity. Community Dev. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kirsop-Taylor, N.; Russel, D.; Winter, M. The Contours of State Retreat from Collaborative Environmental Governance under Austerity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072761

Kirsop-Taylor N, Russel D, Winter M. The Contours of State Retreat from Collaborative Environmental Governance under Austerity. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072761

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirsop-Taylor, Nick, Duncan Russel, and Michael Winter. 2020. "The Contours of State Retreat from Collaborative Environmental Governance under Austerity" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072761

APA StyleKirsop-Taylor, N., Russel, D., & Winter, M. (2020). The Contours of State Retreat from Collaborative Environmental Governance under Austerity. Sustainability, 12(7), 2761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072761