Abstract

In Pakistan, as in other developing countries, rural women make ample contributions to the economy through vital productive and reproductive roles. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of women’s traditional economic activities that supplement their household economy directly through earning income and indirectly through savings expenditure and to assess the factors that influence their productivity performance. For this purpose, six rural areas from Khyber, which is located in the Pukhtoonkhwah province, were chosen to represent the south, north, and the central plain regions. About 480 women responded out of 600, which were selected using a snowball sampling technique from the entire three regions. The data was collected by conducting face-to-face interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs). About 68.33% respondents were illiterate, 47.71% were 31 to 40 years old, and 47.92% lived in a joint family system. Due to the strict Purdah (veil) culture, about 71.88% of the women’s economic activities were confined indoors, such as stitching; embroidery; basket and candle making; preparing pickles, jams, and squash; dairy products; apiculture; sericulture; livestock; poultry; nursery raising; and some agriculture-related off-farm activities. It was reported that the major decisions in the household are made by the male members due to the strong patriarchal norms and values. Development projects by the NGOs and the government have played a significant role to provide credit, training, and awareness that has arisen specifically in the north and the south regions. All of the women were aware of the positive effects of economic independence, but some of them also revealed the negative effects on their physical and psychological health as well as the social ties within the households and communities due to the extensive workload and time issues. The study concluded that many demographic social, cultural, religious, and economic factors negatively influence the women’s productive potential.

1. Introduction

Childcare is considered as the primary concern of women [1]. A mother spends significantly more time with child-related tasks than with any other family member. Child-related tasks include holding, cleaning, and feeding their children [2], which makes women the prime caretaker of the children [3,4]. Maternal responsibilities and caregiving persistently clash with opportunities, and it is time for women to participate in economic activities [4,5,6,7]. As a result, women are often deprived of employment, education, health, and justice.

The Beijing Platform for Action and Millennium Development Goals for gender equality and women’s empowerment also signifies the need to promote the economic independence of women, which include decent jobs, the sharing of non-agricultural employment, productive possessions, public services/facilities, and opportunities [8]. Gender inequities need to be addressed in order to enhance women’s potentials and their freedom of choice [9] to ensure a social and personal change in mutually interlinked socio-economic [10], political, and psychological domains that reinforce freedom for the lives of women [11].

The Pukhtoon caste is one of the most dominant castes in Pakistan that are represented by a strict patriarchy and religious-based norms and customs. The Pukhtoon culture has been highlighted since the time of Herodotus (484–425 BC). Also, Alexander the Great explored this culture in Pakistan and Afghanistan in 330 BC. The Pukhtoon cultural is strongly patriarchal. and women normally wear a veil, but they can be seen in fields helping men. However, urban women from well-off families stay at home, raise their children, and take care of family matters [12]. Similarly, the status of rural women in Pakistan is defined by their community, traditions, cultures, household incomes, living patterns, casts, and many other aspects [13].

Women often face seclusion and exclusion based on the socio-cultural norms of patriarchy that ultimately limit their access to development and empowerment [14]. Being deprived of the basic legal rights of participation in economic activities, restriction on work outside the home, a lack of education and skills, wrong interpretations and implementations of purdah, and the honor associated with the women’s sexuality, domestic workloads, and the lack of awareness about the market make them dependent on their male counterparts, and they are ignored in the nation’s mainstream development process [15]. As a result, the males get attention in every domain of life for better opportunities that include food, education, ownership, decision making, and the power of the resources [16]. Pakistan’s GDI (Gender-related Development Index) is ranked at 120th out of the 146 countries, and its gender empowerment measurement (GEM) is ranked 92 out of the 94 countries [17]. Pakistani women are mostly engaged in unpaid and unacknowledged activities that lead them to be the most underprivileged with no compensation or recognition [18]. Hence, the exclusion of these women from development plans has resulted in the loss of large productive potential [19].

Generally, the rural women that were expelled had no specific entrepreneurial skills, but they were attempting to establish livelihoods and self-sufficiency. Under strict patriarchy, only men are considered responsible to fulfill all the basic needs for their family, and women are supposed to stay inside the houses as primary caretakers for the family’s health and nutrition, bearing and raising children, household management, fetching water and fodder, and fuel wood collection. These women were also engaged in some economic activities to provide income for their sustenance and to contribute to the household economy. Some government and non-government development interventions assist women in their economic efforts. For example, women can perform a significant part to uplift the social and economic standards of their families through microcredit services [20]. Other supporting roles are provided by the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) and non-governmental organizations, such as Barani Area Development Project (BADP), the Saiban International organization, and the Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP). The main purpose of these programs is to strengthen both the income-generating capacities and the national policies to enhance women’s income-generating opportunities to mitigate rural poverty. These women’s organizations assisted with traditional activities through the provision of microcredit, improving health facilities, water supply schemes, and capacity-building skills training, such as leadership and accounting, skill-based training like carpet weaving, crop production, poultry raising, and footwear production to assist rural women’s decision-making power through awareness and economic independence. A similar explanation is given by Hoque and Itohara [21] regarding the development organization’s role influencing the decision making of the rural women to participate in economic activities.

The economic empowerment of women requires a thrust and a willingness for change of the women themselves, which involves their abilities, awareness, and self-respect, reforming the institutions and the communities following modification in norms and behavior, and enabling economic environment with conducive value chains and markets and supportive legal and political environments [22]. However, the working conditions for women are very challenging almost everywhere. If participation in productive activities makes them economically independent on one hand, it increases work burdens, exploitation, and social violence on the other [23]. Whether engaged in wage work or running their enterprises, they are challenged by discriminations and hindrances regarding the division of labor, customary laws, working conditions, wages, decent jobs, freedom of expressions in major decisions, political rights, access to information and technology, and law enforcing agencies. Under the strict patriarchal system, they have to face restricted mobility under the obligations of family honor, religion and customs, humiliating attitudes toward their development, social insecurity, society’s stereotypes, and they also face restrictions that affect their social and economic growth, which is even worse, and it often lead to adverse effects on their mental, physical, and psychological health. These factors are the consequences of gender disparity and misinterpretation of cultures and religions, making them unhappy and dissatisfied with their lives and sometimes even more unhappy and miserable than non-working women.

It is believed that rural women’s access to different resources has a major influence on the wellbeing of the households and expands their livelihood options [24], but most of these livelihood activities are not considered to be active employment. Their domestic activities are not valued and are seldom considered productive activities because they are not paid. Hence, they are not recorded in the national accounting systems [25,26]. Much of their work goes without remuneration and acknowledgment because it is confined to the domestic realm again and again. Caring for children and older family members, fetching water, and collecting fuel for cooking and heat are mostly assigned to women and girls as socio-cultural obligations [27]. Besides performing valuable agricultural tasks, these women are largely kept engaged in unpaid domestic obligations, and women’s efforts remain neglected and invisible in development policies [28]. These women are ignored, unseen, unvoiced, and unappreciated in the development plans, which results in a potentially large untapped economic contribution [19]. As a result, women’s ample input is overlooked in conservative agricultural and economic studies, and men’s input is the exclusive focus of attention [29,30]. The root cause for no acknowledgment of the women’s domestic activities is because these activities are seldom considered as generating income and are valued in terms of non-economic criteria, such as sex that poses serious questions on gender equity and human justice [31].

Being traditional societies, it was also hypothesized that demographic, social, economic, and cultural factors would interfere with the women’s economic activities. One of the barriers to translating women’s issues into development plans is the lack of an adequate database on what women do and why. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of women’s traditional economic activities on their household economy directly through supplementing the household income, indirectly through the savings expenditure, and to assess the factors that influence their productivity performance. In order to achieve the aim of the study, the following hypotheses are presented.

Hypothesis 1. (H1)

Pakistan’s rural women make significant and positive contributions to their household economies.

Hypothesis 2. (H2)

Rural women’s traditional economic activities have a significant and positive impact on their socio-economic empowerment.

Hypothesis 3. (H3)

Socio-cultural, and economic factors influence women’s productive potential differently.

Hypothesis 4. (H4)

Development interventions by governmental and non-governmental organizations significantly promote women’s traditional economic activities.

The Proposed Model

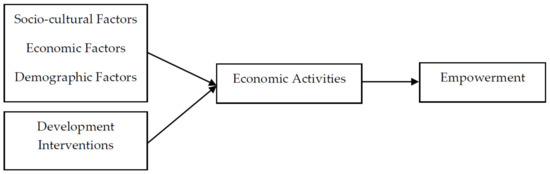

The conceptual model is proposed to grasp the relative influence of the different types of factors and the development interventions on women economic activities, which are involved in the women’s empowerment enhancement (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

2. Methodology

The province was theoretically divided in three regions, which included the Central Region with seven districts and 45% of the entire province’s population, the Southern Region with seven districts and 20% of the entire province’s population, and the Northern Region with 10 districts with 35% of the entire province’s population [32]. In the second stage, one district in each of the regions and two rural areas in each district were selected, which included District Peshawar in region 1, District Karak in region 2, and District Abbottabad in region 3. It was assumed that all of the three regions were more or less the same regarding socio-economic conditions, and the women were actively involved in different economic activities. Before the collection of the primary data, personal visits were made to these areas, and the houses were identified where the women were actively engaged in various economic activities through the snowball sampling technique.

Personal Parameters of the Respondents

The data was collected from February to April 2019. Out of a total of 600 women contacted, around 480 women, which was 80% of the respondents, willingly provided information through interviews and focus group discussion techniques. These women were apprised of the study’s purpose beforehand in order to gather relevant and correct information. In addition to this, careful personal observations and keen examinations of the ground realities also supplemented the primary data. The data was then analyzed to discuss the results and to formulate the recommendations. The characteristics of the respondents are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

The research study area, the sample selection, and the respondents.

In the present study, a greater proportion of the respondents were in the 31 to 40 years old age bracket (47.71%), about half were married (50.63%), over 2/3 were illiterate (68.33%), and most of them belonged to the Pukhtoon caste (82.29%) (see Table 2). One of the possible quoted reasons for the higher illiteracy rate is that these women were at the age where girls’ education was not very much acknowledged in the past. All the respondents could read the Holy Quran as part of their religious education.

Table 2.

Personal parameters of respondents.

3. Results

3.1. Status of the Household Economy

It was found that the majority of the households fell within the poverty class at a low-income level. Agriculture was the major family occupation, which is based on the culture, for most of the respondents (34.38%), which was followed by livestock as the second major occupation (29.79%). About 45.83% of the respondents reported a monthly household income between 21,000–30,000 PKR. The monthly household expenditure was 21,000–30,000 PKR, which was reported by 45.42% of the respondents with monthly savings of 11,000–20,000 PKR, which was reported by 66.25% of the women. The reason for this hand to mouth economic status was that the majority of the respondents belonged to the joint family system (47.92%), with lesser earning members compared to the dependent non-earning members. It was discovered that most women respondents (54.79%) on average had 4–6 children that were dependent on them. In Pakistan, early age marriages of females under the notion of religion and customs influence their tendency to work and ultimately affect their productive capacity particularly in the rural areas (more details can be seen in Table 3). Moreover, early age marriages exert an additional burden on the household economy, which leads to larger families with illiteracy, poverty, dependency, child labor, and many other socio-economic complications. As stated by Gondal [33], the nuclear family set-up, the number of children, the age and the literacy of the husband, and annual household income have a stronger influence on the participation of married females in the economic endeavors in Pakistan.

Table 3.

Status of the household economy.

3.2. Participation in Traditional Economic Activities

As previously mentioned, our respondents performed different tasks that were assigned to them and also some significant economic activities according to their skills, the availability of raw materials, the demand of the community and the market, acquired training, and the availability of time and money. It is worth mentioning that women were engaged in more than one economic activity except for those who were specialized in some specific activities through some training, market demand, or as a major household occupation. The probable reason for women working in more than one economic activity was found the household’s low-income level, a large number of dependents, and a large size family. It was also found that some development organizations were active for women’s capacity building, empowerment, and poverty reduction. Women’s different economic activities are broadly classified as agriculture and horticulture, livestock and poultry, food processing and preservation, making handicrafts, apiculture, and sericulture. Naser et al. [34] explained in their study that women’s individual and external factors could influence the women’s decisions and choices to start their own businesses.

All the women were quite aware of the fact that they could either earn income or save household expenditure through their direct or indirect involvement in economic activities. Table 4 and Table 5 reveal the participation of the rural women’s participation in traditional economic activities. In poor households, about 26.04% of the women stated that they started these economic activities in order to contribute to the household economy by sharing some of the expenditures, while others, which included 20.63% and 18.33%, started these activities for economic independence and to better educate their children, respectively. Another relatively small proportion of women, which included 13.75%, 12.29%, and 2.29%, also reported that they started their own businesses due to the motivation from the development organizations, for better health facilities/better living standards, and as a sole source of income, respectively.

Table 4.

Types of rural women’s traditional economic activities.

Table 5.

Socio-economic status of rural women engaged in traditional economic activities.

Our respondents in the selected study area were found to be actively involved in many skill-based activities in order to support their families directly through the growing and preservation of fruits and vegetables and keeping poultry and other animals, which included indirect small-scale trading, such as selling milk, eggs, dung cakes, and hand-made products. The majority of the women were carrying out these activities as part of their routine domestic work. Only the activities through which the women respondents were earning remunerations directly were recorded. These activities included preparing pickles, jam, squashes, dry fruits, and dairy products such as cream, butter, lassi, desi ghee, and yogurt. Some women also stitched clothes, embroidered clothes, and knit sweaters, caps, and shawls. Also, candles, honey, silk, carpets, baskets, dyed clothes, fresh fruits, vegetables, seeds, dung cakes, eggs, and chickens are items that the women provide in the market in order to get a handsome profit for their domestic expenditures. These results are consistent with those of Butt, Hassan, Khalid, and Sher [15] and Jamali [17].

The respondents in the entire study area were engaged mostly in the activities that they could perform inside their houses (71.88%), except for a small proportion, which included 14.17% that worked outdoors and 13.96% that worked both indoors and outdoors. The women either worked with the males on the family farms, or they did not have a male family member to earn income. The results are consistent with those of Halim and McCarthy [35], and these activities were mostly confined inside the homes, such as managing food, health, and other basic needs of the children and the other family members, so they were mostly engaged in agricultural and non-agricultural activities within their homesteads.

The results depict that the personal monthly income of most of the respondents (57.29%) was between 11,000–20,000 PKR, which included monthly savings reported by 87.08% of women that were below 10,000 PKR. The personal income, savings, and expenditures of a respondent also depend on the total income of the household, the ratio of the dependents and the earning family members, and the extent of poverty. Generally, rural women have fewer rights to resources in order to run their own businesses. Even if they started their businesses, the earned income eventually goes to their husbands. In this study, the reasons for zero or less savings was mostly because the earned money is either utilized in the household or invested again in the economic activities. Other possible reasons were a household’s poor economic conditions, the lack of a nearby market, the inappropriate market price of the products, and no fair price earned for the products that are mostly sold to customers in the community. The responses for zero or less saving varied, such as high household expenses (49.17% women), male dominancy (27.92%), and investment in raw materials (16.04% women). Here, 6.88% of the women reported that their savings are mostly invested in uncertain events, such the marriage of children or relatives, the treatment of ill family members, and sometimes as a result of disasters.

With regard to the husband’s education status, almost equal responses were returned by the majority of the educated men in the Central Region, which is Region 1 and the District Peshawar. As far as the attitude of these males toward women working is concerned, 34.79% of the women reported that the males were slightly satisfied with their earnings, which were due to reasons that involved these activities being inside the houses and contributed to fulfilling the basic needs of the household. There were some respondents (16.25%) who reported that the male members of the household were highly dissatisfied or annoyed with the women’s economic activities, which was due to traditional patriarchal thinking. This type of male dominance was most obvious in the southern region, which was Region 2 and the District Karak, with a great influence of the Pukhtoon culture.

Among the various economic activities, the greatest number of responses was collected for livestock and poultry care, which included 213 out of 480 or 44.38% of the total respondents. The respondents of the all three regions were actively involved in this work both as their routine work as well as for commercial purposes. Women’s perceived kind nature and patience in rearing and treating animals make them the sole caretaker in many cases. The major of the activities carried out by these women included making sheds for the animals, fodder collection and cutting, milking, dairy products making, poultry care, preparation of fuel and manure from animal waste, breeding animals, bathing of animals, hatching of eggs, treatment of sick animals, and the feeding and grazing of animals. The other activities involved making handicrafts, which included 193 out of 480 women or 40.21% of the total respondents. The major activities in this category included stitching, embroidery, knitting, basket making, carpet weaving, and candle making. The same results were included by Bishop and Scoones [36], García [37], Kamdem [38], and Samanta [31].

Food processing and preservation, which was reported by 176 of the 480 women or 36.67% of total respondents, was also a significant activity that was conducted by our respondents. The reported activities in this category involved preparing fruit jams, marmalades, squash, vegetable pickles, ketchup, and the drying and dehydration of vegetables and crops, such as spinach and turnips. The reason for these activities was to preserve additional fruits and vegetables for domestic purposes, reduce expenditures, and sell goods in the community and the marketplace.

Similarly, women were also engaged in honey beekeeping and silkworm rearing for domestic and commercial purposes. Out of the 480 respondents, 129 women (26.88%) indicated that apiculture or sericulture was part of their economic activities. The responses for agricultural activities are quite low because it is considered to be purely men’s responsibility to work in the fields outside the houses. Even then, women were seen in many activities that were agriculturally based, such as weeding, winnowing and cleaning, kitchen gardening, seed sowing, harvesting, threshing, nursery growing, vegetable fruits picking, and fodder cutting for the animals. Most of these economically significant activities were carried out as routine domestic work in order to assist their male counterparts with no rewards or remunerations. However, there were few cases where the women were being rewarded, such as with kitchen gardening, nursery raising, weeding, seed sowing, and fodder cutting by older age women, widows, or poor women who mostly did not have male members in their households. The women working in this category included 120 women out of 480 respondents or 25.00% of the total respondents.

The women’s role in livestock is very significant from an economic and environmental sustainability point of view. It is a fact that the waste material from animals has several benefits for human beings if it is properly processed to be used as fuel and heating purposes. Also, it is useful for agricultural purposes in the form of manure in order to increase soil fertility and the production of crops and fruits/vegetables. The reported activities of the respondents consistent with those from Alsop and Heinsohn [39], Ibraz [40], and Sarwar et al. [41], which illustrate that, in rural areas, looking after livestock is considered the prime concern of rural women. Among the various significant activities is the collection of fodder, the cleaning of animal structures, and the processing of food products. Likewise, rural women contribute significantly to agriculture, includes seeding and land preparation; farmyard manure collection and preparation; weeding and hoeing; pickling and harvesting; cleaning, drying and preserving grains; and other activities after the harvesting has been completed. Besides agricultural activities and livestock rending operations, they are also involved in handicrafts.

3.3. Management of Paid and Unpaid Activities

A woman in any society contributes significantly to building a strong and healthy nation. These women are actively involved in both domestic and productive activities, and they bear double responsibility for the family’s nutrition, health, and education inside and outside the household, which is mostly on family farms. They are the first to wake up and begin the domestic chores, and they are the last to go to sleep. Their working hours range from 9–13 h a day. They are always craving to be successful in their multiple responsibilities as mothers, even though these responsibilities are frequently disrupted from the perspective of the household’s poverty [42,43,44,45].

Like other rural women, our study respondents whether educated or uneducated, married, unmarried, or widowed are involved in various domestic activities from dawn to dusk, and 43.47% of the women reported that they spent 6–10 h a day on domestic tasks, such as cooking, fetching water, cleaning, and washing as unpaid productive activities. This means that every woman spends more than half of the day on average working and taking care of children and old age dependents. A majority (45.42%) of them were managing their household activities themselves, and 41.04% of the women were managing their household activities with the assistance of other family members if they lived in joint and extended family systems (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Management of paid and unpaid activities by women.

In the present study, it was an appreciable fact that, besides managing their domestic chores, rural women were keenly involved in varied traditional economic activities. Being cognizant of the productive capacities of the contribution to some extent in the household economy, 69.79% of them were engaged in economic activities, and they sacrificed their leisure time, rest time, and other social activities. They spent an average of 4–6 h on these activities. Almost 47.71% of the women reported that the available time for rest is less than their health requirement. Most of their time is spent on domestic activities, and almost the same proportion (41.88%) reported satisfaction with the available rest time. These women mostly belonged to a joint or an extended family system, which have other family members to help with the domestic activities. As stated by Gondal [33], married women’s participation in economic activities has a stronger association with the nuclear family structure, children’s ages and numbers, the husband’s age and literacy level, and the annual household income in Pakistan. Similarly, the leisure time of the women is defined by Dixon-Mueller [46]. The result is also in line with that of Ali [47]; Biswas, Bryce, and Bryce [2]; Chaudhry et al. [48]; Gondal [33]; Grace [49]; Halim and McCarthy [35]; Mason [4]; McIntyre, Glanville, Raine, Dayle, Anderson, and Battaglia [3]; McPhee and Bronstein [6]; Niamir-Fuller [50]; Roy, Kulkarni, and Vaidehi [45]; Shaleesha and Stanley [1]; and Tyyska [7].

3.4. Source and Value of Traditional Economic Activities

In the previous discussion, it was quite evident that almost all the respondents belonged to low-income families with little savings and liquidity available for investment. In this scenario, the availability and the purchase of raw materials and the market for final products also affects the choice and the extent of the women’s motivation and zeal to participate in traditional economic activities. In the present study, it was discovered that most women (42.92%) rely on their household produce, such as crops, vegetables, fruits, milk, and dung, and there were few exceptions who purchased the raw material from the market (26.25%). Also, roughly 1/5 of the women (19.58%) received assistance from the development organizations that work for poverty reduction and women empowerment, and only 10.21% of the women received assistance from the community to start and run their traditional ventures (See Table 7).

Table 7.

Source and value of traditional economic activities.

The satisfaction of the respondents was also dependent on the total household income, living standards, expenses, number of family members (ratio of dependents and earning members), personal savings, and the attitudes of the family members (especially males). Regarding the price value of their produce, it was noted that the women were not very happy with the price and the reward they obtained for their products. Almost all of them stated that they could fetch higher prices for their products if they were facilitated with proper marketing services. Almost 34.17% of the women reported very slight satisfaction with the price value of their products, and only 6.88% were extremely satisfied with the income. Moreover, more than half of the products, such as poultry, eggs, milk, preserved food, honey, and clothes, were either consumed within the household (32.29%) or sold in the nearby community (26.46%) at lower prices. The remaining 41.25% of the women declared that they sell their products at the market. The probable reasons for selling the products at cheaper prices in the community were the lack of a nearby market, restricted mobility of the women to the market, restriction on sale or purchase of raw materials themselves, and high transportation costs. These findings are consistent with Cavalcanti and Tavares [51], who stated that women’s labor market output, wages, capacity for choices, and agencies are affected by gender inequalities, discrimination, and a range of factors that include social norms that may vary across regions and the country.

3.5. Effects of Traditional Economic Activities on Rural Women’s Lives

Empowerment plays an important role in most of the aspects of the peoples’ lives [52,53]. The concept of empowerment implies woman’s consciousness of self-esteem, self-identity, eagerness, and the potential to resist a subordinate position and identity her ability to observe strategic control over her life and to negotiate associations with those who are inevitably superior to her. Women’s ability to contribute on equality basis to restructure societies that they reside in for democratic and the fair distribution of power and development potentials are necessary [54]. Women’s participation in economic activities has effects on their lives in terms of their decision-making power [55] and empowerment in terms of expanding human rights, resources, and the ability to act independently in different social, political, and economic spheres [56].

To assess the effects of women’s traditional economic activities on their lives, they were asked questions regarding their lives before and after starting economic activities inside and outside the household with the other community members, on their family member’s lives, on their living standards, the socialization of their children, their social linkages, and their decision making power.

Almost all of the respondents agreed that their economic participation has a good effect on their lives, which enables them to be economically independent and fulfill their basic needs themselves (70.42%). Moreover, 56.88% of the women also reported that these economic activities were very helpful to make good linkages with the community members through the selling of their products, while 45.21% stated that their living standards were uplifted as a result of their participation in economic activities. Some of them (51.88%) were convinced that by contributing to the household economy, these women were also assisting with providing better education for their children and other young dependents. A significant proportion of the respondents also highlighted the positive effects of the economic activities with improving their living standards (45.21%) (See Table 8 and Table 9). The results are in line with Dixon [57], which stated that organizing self-reliant economic activities make women not only economically independent, but they also lead to positive outcomes in a range of women’s decision-making power to lower fertility rates to produce less children.

Table 8.

Positive effects of economic activities on women’s lives.

Table 9.

Positive effects of traditional economic activities on women’s access and control over resources.

Almost all of the respondents belonged to conservative families with mostly negative attitudes regarding women’s mobility and socio-economic freedom. Being convinced by women’s positive contributions to the household economy and assisting in reducing household expenditures, the male members of the family, such as the husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons, also changed their attitudes toward women working in some cases. This was a very positive indicator of women’s empowerment through reforming the existing gender division of labor (reported by 32.71%). Moreover, it was observed that these respondents felt honored and encouraged compared to others, while they narrated the positive attitudes of their men toward their work. Various studies on the impacts of the men’s support or resistance toward women’s work and empowerment have revealed that approval or support from the male family members, specifically husbands and fathers, have greater positive effects on women’s psychological, social, and economic wellbeing. A similar fact is stated by Hast [58], which mentions that a family is the main unit that employs a greater proportion of gender interactions. Men as fathers and husbands have a greater contribution to the physical wellbeing and the socio-economic outcomes of women, and they bring about gender equality both in developed and developing countries. It is generally believed that men in almost every society have dominance and superiority in many spheres of life. Specifically, in developing countries, which includes Pakistan, men are in full charge of the economic resources, and they have full control of women’s health and socio-economic matters in some cases. This unequal allocation of family care and domestic chores in the developed world is considered a barrier to the productive potential of women.

Only 22.92% of the women respondents stated positive effects in the decision-making area, which only a few of them were able to exercise their decisions for their family members who were mostly dependents (children, elders), and almost all of them were deprived of decision-making power for themselves. This was a very depressing fact, because even though they were economically independent, their major life-related decisions were handled by others. The reason behind this depressing finding is rigid culture and a lack of awareness regarding women’s rights. Most of them consider it a part of modesty, and they are obliged to hand over their major life-related decisions to their male counterparts, always trying to remain silent and humble and be content with their subordinate position. As previously stated, gender inequality is the difference in the status and power of women and men, so power is gendered. Specifically, men (relative to women) enjoy greater control of resources, have less social compulsions to uphold, and culturally dominate ideologies in the various domains of life [59,60,61]. This is very common in rural areas because women utilize their children, other females, and the males of the family to some extent for assistance with domestic and economic activities or for assistance with day to day life.

As these respondents belonged to a traditional rigid patriarchal culture, most of the decision making was made by the men, which was either the father, husbands, brothers, and even sons. Cain et al. [62] explained that, traditionally, under patriarchy, the decision-making power within families is in the hands of the men, which makes women powerless and dependent on men.

While mentioning the positive effects, almost half of the respondents also narrated the negative effects of economic activities on their physical health (22% due to extensive work), mental health (19% due to restlessness and financial pressure), and social ties and harmony (18% due to time, money, and expectations), which is same as reported by Dunn [63] and Terjesen and Elam [64]. These results are provided in Table 10.

Table 10.

Negative effects of traditional economic activities on women’s lives.

3.6. Factors Influencing Rural Women’s Traditional Economic Activities

Even though drastic development changes have taken place over the past 20 years, these changes have not alleviated poverty or women’s vulnerability [65]. The socio-cultural factors that affect female participation and their labor input and income activities are the age of the women, the education of the adult males, the husband’s occupation, and the socio-economic status of the family [66]. Despite various rural development initiatives, the ratio of the working women to the men is still quite small. The reason for women’s decreased interest and contribution to the economic activities is genuinely very basic, such as no or little access to education, skill development, decent paid work, property, assets, financial services, leadership, and social protection. Moreover, voluntary care and domestic workloads, inappropriate and discriminatory policies, lack of political will, and lack of gender sensitized actors in policymaking, all of which exacerbate the situation.

It has been revealed that all the above-stated factors significantly interfere with women’s performance in economic endeavors (Table 11). The most devastating factor reported by the majority of the respondents (79.79%) is the restriction on mobility to work outside the household or deal with the community or the market due cultural restrictions, because younger women are not allowed to work outside the household or go to the market without permission from their male counterparts. The results are in line with that of Irfan [67]. The other factor reported by 61.67% of the women was illiteracy, because they believe that they cannot use many technologies without assistance from men. These women mostly lack the available benefits of mass media communication and marketing techniques.

Table 11.

Factors influencing rural women’s traditional economic activities.

As women respondents were engaged almost all day long in domestic and economic activities side by side with their men and with economic activities for additional income contributions to the household economy, they reported that time scarcity was one of the major factors that affected their economic activities. Because the majority of the respondents were living in a joint family system, had illiterate and less educated husbands, had low household incomes, and little or zero savings, almost 47.08% reported a financial barrier. As a result, 46.25% of the respondents reported the domestic workload, 45.21% reported the time scarcity, and 42.08% women reported the responsibilities of the dependents, which included children and elderly household members, as the major factors that influenced their productive potential. A similar fact was studied by Hast [58], who illustrated that the women’s time allocation to an income-generating activity is influenced by the division of the labor in the household, the women’s time use pattern, the decision-making power, and some demographic factors. Women within a smaller family system can better deliver and allocate more hours to economic activities. Similarly, women with cooperative husbands who assist in household maintenance could provide more time for their projects.

These results coincide with our study findings that state that the majority of the women respondents in our study that conduct these activities belong to joint family systems. In Pakistan, the likelihood of rural women’s participation in economic activities is higher in large families because of the greater availability of human resources to share responsibility for both domestic and economic activities. Gondal [33] stated that the participation of women in economic activities is negatively correlated with the existence of a nuclear family structure and small children, because they interfere with the women’s time allocation to the economic activities. Similarly, the husbands’ age, literacy level, and annual household income are expected to negatively effect the involvement of married women in economic activities. Other sequentially influencing factors were the lack of skills/training, the lack of access to information and modern technology, religious and political stakeholders, high transportation costs, low market price of the products, and lack of nearby market, which was reported by 41.25%, 40.63%, 40.21%, 38.33%, 38.13%, and 36.46% of women, respectively. Few of them [68] reported that the cost of production and the social conflicts with the family members and the community might also hinder their economic performance and productivity, which was reported by 26.25% and 21.88% of the women, respectively. The same facts were reported by Lovell [69] for the significance of microfinance and credit facilities for women’s economic activities.

Similarly, Islam et al. [70] stated that rural women’s participation in economic activities is also influenced by the access to education facilities, mass media, extension workers, and the husbands’ attitude. Irfan [67] concluded that the women’s age, education, the age of the youngest children, the number of children, the availability of the mother, the husband’s education, the husband’s occupation, the income status, the availability of land, the tenure status, and the use of tractors are the significant factors that influence their participation in various economic activities. The same results were stated by Francis [71], Lin [72], Thakor and Patel [73], Twenge [74], and Van Vuuren et al. [75]. Also, Stevens [76] explained that a woman’s life is affected by socio-economic factors, such as her marital status, employment, income, position in the household, education outcomes, health condition, family structure, access and control over resources, the husband’s unemployment, loans available to the household, urban locality, number of children born (up to eight), the education and religion of the parents, and the region affect women’s lives.

The study revealed that, due to limited mobility and contacts, the limited scale of production, the lack of awareness of the market, the lack of information, and little or no education are the salient factors that affect women’s productivity in terms of disappointment and receiving a lower price than expected, which leaves little profit for savings and investment. This results in the consumption of a significant proportion of the products either in the respondents’ household or sold in the near community just for the sake of earning a few rupees. Others were selling off their products to markets through their male family members because they had no permission to deal with the market themselves. Their products were not valued and rewarded appropriately, so they were mostly unsatisfied with their earned income. As mentioned above, these factors are considered responsible for the quality and the price of the raw material purchased indirectly through their male counterparts who have the least interest. They know little about the women’s productive activities’ requirements and mostly perform it as a liability.

Kabeer [77] stated that women’s work is influenced by gender-based constraints in the domain of family and kinship. Some of these restrictions are the imposition of the men’s dominance over the women’s use of time, their obligation to assist with only the male’s family farms and economic activities, their primary responsibility for the domestic care work, the women’s compulsion to work only in those activities that are socially approved for them, the mobility restrictions in the public domain, and the customary laws with little or no rights over economic resources and property.

Class, caste, and regional differences also have great effects on the women’s economic participation and status [78]. There is some variation in the above-stated findings because the respondents of the three regions belong to different castes and backgrounds, vocational facilities, male education, religious and political influences, social interaction of the area with urban areas, and mostly because of the efforts carried out by women organizations to create awareness regarding women’s development, which provide credit and training. According to Jamil [79], Paul and Saadullah [80], and Younis [81], almost everywhere, which includes educated and uneducated women, women are alike and involved in domestic, productive, reproductive, and community management activities.

3.7. Suggestions by Women Respondents

One thing observed during this study, which was quite appreciable and noteworthy, was that women of the area were quite sensible and aware of their rights and responsibilities in society. Even though they were illiterate, they were not contented with their subordinate position, and they wanted to break these discriminatory locks and were also desperate to quit the vicious circle of poverty. They were trapped by conservative norms and customs, but they did not stop contributing to development though through indoor economic activities. Their contributions to the household economy were small, but they were successful to some extent in changing the mindsets of the society stakeholders toward women’s potential and responsibilities. Their contributions were considered small in regard to monetary value as compared to the past, but this could be counted as a bold step toward the mega goals of poverty reduction and women’s empowerment. This fact was highly supported by the suggestions given by the women respondents for community development through women’s economic activities.

Most of the women respondents (56.04%) suggested training and skills development opportunities to assist women’s productive potential to contribute to the household economy, and an almost equal proportion (52.04%) stated that there was a need to modify the societal norms and values towards women’s rights and socio-economic responsibilities. The other 48.54% and 37.29% of the total women respondents suggested providing micro-credit facilities and appropriate marketing facilities to value their productive potential in monetary terms so that they could convince their families about the advantages of them working through greater contributions to the household to uplift their living standards (see Table 12).

Table 12.

Suggestions by women respondents.

4. Discussion

In almost every society, rural women participate in productive utilities of some type. These economic activities are both income-earning and expenditure saving in nature [40]. It is believed that the primary concern of a woman is the wellbeing of her family. Most women have little time for rest or recreation, work between nine and thirteen hours a day, and have to carry on the essential domestic chores, such as family nutrition, food security, childcare, cleaning, fetching water, and collecting firewood. Outside tasks (such as farm activities, paid or unpaid labor for sowing, weeding, harvesting, animal husbandry, fodder cutting, applying fertilizers and pesticides, threshing, food processing, transport, and marketing) and off-farm economic activities (such as sewing and hand knitting) contribute to the household economy and reinforce livelihood strategies [1,2,42,44,68,82,83,84]. By acknowledging these vital roles in formulating the structures, decisions, and the rules that control their lives, long-term sustainable development can be ensured [43,85,86]. However, women’s significant input has continued to be underestimated in the traditional agricultural practices, economic studies, and policy formulation, and men’s input has remained as the central and sole focus of attention [29,30].

In Pakistan, women account for almost half of the population, contribute substantially to productive labor, and even sometimes exceed men in agricultural activities in addition to performing significant domestic responsibilities, but the socio-cultural set up in Pakistan with gender inequality in the labor force creates a lot of constraints for women’s participation in productive activities. The government of Pakistan has implemented many policies for poverty alleviation through the development of both agriculture and non-farm income opportunities to ensure food security and social justice. Unfortunately, these policies mostly ignore addressing the equity issues that hinder women’s potential to be fully harnessed. Similarly, non-governmental organizations have also devised many policies and implemented interventions to enhance their productivity, but they did not come up with any noteworthy outcomes, mostly because of the traditions and cultures that exist in Pakistan’s rural areas. In rural areas in particular, women are mostly illiterate and are unaware of their rights to development, their lack of access and control over assets, their lack of decision power, their being deprived of decent job training and capacity building opportunities, and their low health standards. Various demographic, social, cultural, political, and religious factors influence women’s lives and productivity potentials in every domain of their lives in the household, community, workplace, labor market, and the overall national level. Most women are restricted to stay inside their houses, or they are confined to family farms and perform domestic and economic activities.

The present study concluded that the majority of our respondents were providing a very crucial role in supporting their families through productive and reproductive roles. Among these various activities, the most important were agricultural, livestock (which includes poultry, milking, feeding, grazing, cleaning the animals’ lodgings), vegetable and fruit preservation, and making handicrafts. The study area respondents mostly belonged to a background with strict cultural norms and customs, so they were not allowed to work outside the home, but these women had not stopped supporting their families even then through the traditional abilities, skills, and talents, which proved that they are as an asset rather than a liability. Younger women were not allowed to go outside with male members, but widows or those women with no earning male members or the elderly were allowed to go and work outside. The majority of our respondents believed that economic activities are supported to raise the household economy and develop good social linkages with the community and the developing world. Factors, such as the lack of a market, the high cost of transportation, the low prices due to a lack of market information, and the dependency on males for raw materials and the sale of their products, affect the women’s work negatively. They also pointed out some other challenges, such as culture and restrictions from political and religious clerics. They also mentioned that if they are provided with technical training, credit, fair market, technologies, and equipment, their income and family prosperity would increase.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Based on the results, it is quite evident that almost all the women in the research area are actively involved in supporting their families by performing productive and reproductive activities to supplement their own needs and to contribute to the household economy. Due to rigid customs and strict societal norms, which exist throughout the entire province, most women stay inside their houses and are not allowed to move freely in the community. For this reason, they are limited by these attributes and develop few skills from the very beginning of their childhood as a result of adjusting with their norms and customs. Various demographic, social, cultural, political, and religious factors influence women’s lives and their economic activities, productivity potentials, and capacities.

From the findings of this study, it is concluded that academic institutions and researchers should highlight the on-the-ground realities and put forth suggestions to develop fairer policies for the empowerment and the development in a true sense, which is not to just merely increased job opportunities and income. More importantly, the nature and the extent of factors that hinder women vary according to women’s age, education, type of family, household income level, caste, ethnicity, rural–urban settlement, and marital status. Therefore, each factor could either be a constraint or an enabler. In this context, a gender sensitized analysis is considered necessary to understand women’s capacities to exercise choices related to their economic, social, and political lives. It also requires a careful analysis and a stronger commitment from all the stakeholders of the society, especially a thrust for change by women themselves to improve their passive condition. There is a need to be realistic about what can be achieved and what can bring additional value and how such a message can be effectively conveyed and understood. It also requires a careful modification of the social norms, legal frameworks, and the policies that lead to gender equality to ensure women’s equal control over resources and their futures, which lead them to development in its true sense with fairness, empowerment, peace, and happiness. Based on this study and the respondents’ opinions, the following suggestions are made.

- i.

- Some need assessment training and surveys should be conducted to identify the women’s direct needs, desires, abilities, and contributions as well as to accurately record the true data with the consultation of the women themselves before conducting any capacity-building training and other development interventions in order to ensure the efficiency and the effectiveness.

- ii.

- Soft credit facilities should be provided for females to enhance their productive potential and to break the deadlock of the vicious circle of poverty in the area and to increase the incomes, the savings, and the investment of the study area.

- iii.

- Advanced, safe, and hygienic techniques should be introduced, and that information should be delivered through easy language and communication channels to the poor and illiterate women regarding the methods of processing and the preservation of various fruits, vegetables, and livestock products.

- iv.

- Adult education programs, education, and skill development training are required in the study area with the inclusion of elder women for valuable information and experience sharing regarding the various aspects that directly or indirectly affect women’s lives.

- v.

- Awareness-raising campaigns are required to support the remunerative working activities of the rural women by interventions and awareness-raising campaigns.

- vi.

- Resource mobilization is required to increase women’s access to savings, credit, and investment schemes and programs to equip them with capital, knowledge, and tools that assist their productive potentials. Access to and the use of critical rural infrastructure, such as energy and transport and public goods, which include water and communal resources, are required.

- vii.

- Policies are needed to address the lack of leisure time, rest hours, and recreational and soothing activities and practices for working women to help them recover from health fatigues and psychological pressures.

- viii.

- Last but not least, fair markets and fair price control mechanisms are required to encourage rural women in their economic activities.

6. Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Future Research

As with all research, the findings of the present research need to be viewed in terms of its limitations. First, the present study was a micro-survey conducted in a few randomly selected parts of the provinces of Pakistan. Therefore, these findings cannot be generalized for the entire population that resides in other parts of the provinces. In order to make accurate policies and more generalized observations, there is a need for more longitudinal studies on the subject matter instead of the micro and the cross-sectional studies.

Second, the sample size and the areas selected for this study were also justified by the limited resources of time, finances, and the societal barriers involved to approach all of the women. For more accuracy, there is a need to ensure a more parallel and meaningful analysis.

Third, the rural women in this study were involved in economic activities, which involved income earnings or expenditure savings. Therefore, it was difficult to differentiate the type and the extent of activities that the women render for their income earnings beyond meeting household needs. In the future, this differentiation should be studied separately in a more focused way. Women can also be studied who are involved in economic activities solely for household expenditure savings as well as for a more comprehensive understanding of the comparison with non-earning.

Fourth, there were some questions where the respondents’ self-perceptions were important to consider as well as the perceptions of other family members, such as their male counterparts with respect to decision making and contributions to the household economy. There might be some differences in opinions with women’s monetary and non-monetary activities and the value of their contributions, especially in the rural areas as compared to the urban areas. In the future, this comparison should be kept in mind.

Fifth, due to the strict patriarchal structure and cultural barriers, some of the respondents were reluctant to provide accurate information because of some previous unpleasant experiences. Therefore, it took more time to gain these respondents’ confidences and make the purpose of the research clearer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.J.; Methodology: S.J., S.H., A.J., A.H., M.A., and A.J.; Validation: J.H. and M.A.; Formal Analysis: S.J. and S.H.; Investigation: S.J.; Resources: A.J., J.H. and A.H.; Data Curation: S.J. and M.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: S.J.; Writing—Review and Editing: S.J., S.H., A.J., A.H., M.A., A.J., and J.H; Funding Acquisition: J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

The study receives no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shaleesha, A.; Stanley, V. Involvement of rural women in aquaculture: An innovative approach. Naga Iclarm Q. 2000, 23, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, W.; Bryce, D.; Bryce, P. Technology in Context for Rural Bangladesh: The Options from an Improved Cooking Stove for Women; International Solar Energy Society: Freiburg, Germany, 2001; p. 1442. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, L.; Glanville, N.T.; Raine, K.D.; Dayle, J.B.; Anderson, B.; Battaglia, N. Do low-income lone mothers compromise their nutrition to feed their children? Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 168, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mason, A. Population change and economic development: What have we learned from the East Asia experience? Appl. Popul. Policy 2003, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, M. Women and their work on Australian farms. Rural Sociol. 1995, 60, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, D.M.; Bronstein, L.R. The journey from welfare to work: Learning from women living in poverty. Affilia 2003, 18, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyyska, V. Women, Citizenship and Canadian Child Care Policy in the 1990s; Occasional Paper No. 13; ERIC: Toronto, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. The Conditions and Consequences of Choice: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment; UNRISD Geneva: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999; Volume 108. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.; Pereznieto, P. Review of Evaluation Approaches and Methods Used by Interventions on Women and Girls’ Economic Empowerment; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, T.; Domingo, P.; Valters, C. Progress on Women’s Empowerment: From Technical Fixes to Political Action; Development Progress Working Paper 6; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gohar, M.; Rauf, A.; Abrar, A. Making of household entrepreneurs: Lived experiences of Pukhtoon women entrepreneurs from Peshawar, Pakistan. In Proceedings of the ICSB World Conference, Stockholm, Sweden, 15–18 June 2011; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yunis, M.S.; Hashim, H.; Anderson, A.R. Enablers and Constraints of Female Entrepreneurship in Khyber Pukhtunkhawa, Pakistan: Institutional and Feminist Perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isran, S.; Isran, M.A. Patriarchy and women in Pakistan: A critical analysis. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2012, 4, 835–859. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, T.M.; Hassan, Z.Y.; Khalid, M.; Sher, M. Role of rural women in agricultural development and their constraints. J. Agric. Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pudup, M.B. Women’s work in the West Virginia economy. W. Va. Hist. 1990, 49, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jamali, D. Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries: A relational perspective. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2009, 24, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, Z.; Khanum, A.; Ali, A.; Saeed, T. The Economic Contribution of Pakistani Women through Their Unpaid Labour; Society for Alternative Media and Research and Health Bridge: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, H.; Nuhu, K.; Shuaibu, H.; Yusuf, H.; Yusuf, O. Factors affecting the involvement of women in income generating activities in Sabon-Gari Local Government Area of Kaduna State, Nigeria. Am. J. Exp. Agric. 2015, 5, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flintan, F. Sitting at the table: Securing benefits for pastoral women from land tenure reform in Ethiopia. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2010, 4, 153–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.; Itohara, Y. Participation and decision making role of rural women in economic activities: A comparative study for members and non-members of the micro-credit organizations in Bangladesh. J. Soc. Sci. 2008, 4, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Golla, A.M.; Malhotra, A.; Nanda, P.; Mehra, R.; Kes, A.; Jacobs, K.; Namy, S. Understanding and Measuring Women’s Economic Empowerment; ICRW: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, A.; Hossain, M.I.; Reaz, M.; Bagum, T.; Tabash, M.; Karim, A.M. Impact of Demographics, Social Capital and Participation in Income Generating Activities (IGAs) on Economic Empowerment of Rural Women in Bangladesh. Test Eng. Manag. 2020, 82, 1911–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Israr, M.; Khan, H. Availability and access to capitals of rural households in northern Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric 2010, 26, 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food Insecurity in the World: Addressing Food Insecurity in Protracted Crises; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, R.K. Empowering Rural Women: Issues, Opportunities and Approaches; Women Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, M.; Paciello, C. Gender dimensions of rural and agricultural and public works programmes. Experience from South Africa. Differentiated pathways out of poverty: A global perspective. In Gender Dimensions of Rural and Agricultural Employment: Differentiated Pathways out of Poverty, Status, Trends, and Gaps; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; The International Fund for Agricultural Development: Rome, Italy; The International Labour Office: Rome, Italy, 2010; pp. 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, D.P.; Minnotte, K.L.; Mannon, S.E.; Kiger, G. Examining the “neglected side of the work-family interface” Antecedents of positive and negative family-to-work spillover. J. Fam. Issues 2007, 28, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiggins, J.; Samanta, K.; Olawoye, J.E. Improving women farmers’ access to extension services. In Improving Agricultural Extension a Reference Manual; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1997; pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiyi, E.; Danladi, B.; Akande, K.; Mahmood, Y. Role of women in agricultural development and their constraints: A case study of Biliri Local Government Area, Gombe State, Nigeria. Pak. J. Nutr. 2007, 6, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malhotra, M. Empowerment of Women: Women in Rural Development; Isha Books: Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Hayat, Y.; Habib, Z.; Iqbal, J. Rural-Urban Disparities in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric. 2011, 27, 477–483. [Google Scholar]

- Gondal, A.H. Women’s involvement in earning activities: Evidence from rural Pakistan. Lahore J. Econ. 2003, 8, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, K.; Nuseibeh, R.; Al-Hussaini, A. Personal and external factors effect on women entrepreneurs: Evidence from Kuwait. J. Dev. Entrep. 2012, 17, 1250008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, A.; McCarthy, F.E. 14 Women laborers in rice producing villages of Bangladesh. In Women in Rice Farming, Proceedings of the Conference on Women in Rice Farming Systems, Manila, Philippines, 26–30 September 1983; Gower Publishing Company Limited: Aldershot, UK, 1985; p. 243. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J.; Scoones, I. Beer and Baskets: The Economics of Women’s Livelihoods in Ngamiland, Botswana; IIED Research Series; IIED: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- García, V.V. “Respecting your home”: Economic change and gender ideology in a native community in Southern Veracruz, Mexico. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 1996, 17, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdem, M.S. Basket-Making, a Rural Microenterprise in Africa (North-Cameroon). Frankf. Wirtsch. Soz. Schr. 1993, 63, 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Alsop, R.; Heinsohn, N. Measuring Empowerment in Practice: Structuring Analysis and Framing Indicators; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ibraz, T.S. The cultural context of women’s productive invisibility: A case study of a Pakistani village. Pak. Dev. Rev. 1993, 32, 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, M.; Saleem, M.A.; Khan, M.J. Baseline Study of Punjab Small Holders Dairy Development Project, Gujranwala; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.; Gupta, B.K. Role of women in economic development. Yojana 1987, 31, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Akhter, S.; Banu, S.; Sarker, N.; Joarder, R.; Saha, R. Women in farming and income earning: Study of a Gazipur village. J. Rural Dev. Bangladesh 1995, 25, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Oladeji, J.; Olujide, M.; Oyesola, O. Income generating activities of Fulani women in Iseyin Local Government area of Oyo State. Stud. Tribes Tribals 2006, 4, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, T.; Kulkarni, S.; Vaidehi, Y. Social inequalities in health and nutrition in selected states. Econ. Political Wkly. 2004, 39, 677–683. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Mueller, R. Women’s Work in Third World Agriculture: Concepts and Indicators; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. The impact of micro credit on livestock enterprise development in district Abbottabad (A case of SRSP micro credit programme). Sarhad J. Agric. 2007, 23, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, M.G.; Khan, Z.; Abella, M. Female Labour Force Participation Rates in Rural Pakistan: Some Fundamental Explanations and Policy Implications [with Comments]. Pak. Dev. Rev. 1987, 26, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J. Gender Roles in Agriculture: Case Studies of Five Villages in Northern Afghanistan; AREU: Kabul, Afghanistan, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Niamir-Fuller, M. Women Livestock Managers in the Third World: A Focus on Technical Issues Related to Gender Roles in Livestock Production; Staff Working Paper Series 18; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti, T.; Tavares, J. The Output Cost of Gender Discrimination: A Model-based Macroeconomics Estimate. Econ. J. 2016, 126, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Hwang, J.; Sahito, N. Linking Transformational Leadership with Nurse-Assessed Adverse Patient Outcomes and the Quality of Care: Assessing the Role of Job Satisfaction and Structural Empowerment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Mainstreaming Gender in Social Protection for the Informal Economy; Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mizan, A.N. In Quest of Empowerment: The Grameen Bank Impact on Women’s Power and Status; University Press Ltd.: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, P.; Onofa, M.; Ponce, J. Information Technology and Student Achievement: Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Ecuador; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R.B. The Roles of Rural Women: Female Seclusion Economic Production and Reproductive Choice; Population and Development, Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hast, M. Time Supply Behaviour of Women in Income-Generating Project: A Case Study of Women in the Seed Multiplication Project, Mkushi, Zambia; Nationalekonomiska Institutionen: Lund, Sweden, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, A. Sex, Gender and Society; Maurice Temple Smith Ltd.: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto, F.; Walker, A. The Bases of Gendered Power. In The Psychology of Gender; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pratto, F.; Lee, I.; Tan, J.; Pitpitan, E. Power basis theory: A psycho-ecological approach to power. In Social Motivation; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2011; pp. 191–222. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, M.; Khanam, S.R.; Nahar, S. Class, patriarchy, and women’s work in Bangladesh. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1979, 5, 405–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, K. [The busiest people in the world]. [French]. Ceres. Rev. FAO 1995, 27, 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Terjesen, S.; Elam, A. Women entrepreneurship: A force for growth. Int. Trade Forum 2012, 48, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Onyebu, C. Assessment of income generating activities among rural women in Enugu state, Nigeria. Eur. J. Bus. Econ. Account. 2016, 4, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bahar, S. Women in Crop Production and Management Decisions in Barani Punjab: Implications for Extension; PARC: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, M. The determinations of female labor force participation in Pakistan. In Studies in Population, Labour Force and Migration; Project Report No. 5; Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE): Islamabad, Pakistan, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, S. Women labour-unrealized potential. Dawn, 27 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, C.H. Breaking the Cycle of Poverty: The BRAC Strategy; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.; Bhuiyan, A.; Karim, A. Women participation in agricultural income generating activities. J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh Sci. 1996, 22, 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, E. Gender, migration and multiple livelihoods: Cases from Eastern and Southern Africa. J. Dev. Stud. 2002, 38, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Women and rural development in China. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 1995, 16, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, R.; Patel, K. Influence of socio-psychological correlates on farm women’s contribution in mixed farming. Gujarat Agric. Univ. Res. J. 1997, 23, 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge, J.M. The age of anxiety? The birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952–1993. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, J.; Nieman, G.; Botha, M. Measuring the effectiveness of the Women Entrepreneurship Programme on potential, start-up and established women entrepreneurs in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2007, 10, 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, C. Are women the key to sustainable development? Sustain. Dev. Insights 2010, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Women’s Economic Empowerment and Inclusive Growth: Labour Markets and Enterprise Development; International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012; Volume 44, pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz, M. Determinants of female labor force participation in Pakistan an empirical analysis of PSLM (2004–05) micro data. Lahore J. Econ. 2007, 12, 203–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, K. The Determinants of Women Labor Force Participation in Pakistan. Master’s Thesis, Department of Economics, Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, D.; Saadullah, M. Role of women in homestead of small farm category in an area of Jessore, Bangladesh. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 1991, 3, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, M. Providing encouragement and skills. The Nation, 20 August 2000; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, Y. Human development and women in development. Res. Bull. Obihiro Univ. Nat. Sci. 1996, 19, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marilee, K. Crucial role of women in food security in Oyun local government area of Kwara State, Nigeria. World J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 9, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, H.; Ali, T.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.I. Capabilities and competencies of Pakistani rural women in performing house hold and agricultural tasks: A case study in tehsil Faisalabad. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 46, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.L. From Unheard Screams to Powerful Voices: A Case Study of Women’s Political Empowerment in the Philippines. In Proceedings of the 12th National Convention on Statistics (NCS) EDSA, Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 1–2 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hunger, A.A. Feeding Hunger and Insecurity: The Global Food Crisis; Briefing Paper, Action against Hunger; ACF International Network: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).