An Investigation of the Influencing Factors of Chinese WeChat Users’ Environmental Information-Sharing Behavior Based on an Integrated Model of UGT, NAM, and TPB

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What factors of gratification motivate WeChat users’ environmental information-sharing behavior?

- (2)

- What altruistic factors impact Chinese WeChat users’ environmental information-sharing behavior?

- (3)

- How do the motivational factors impact the decision-making process of Chinese WeChat users’ environmental information-sharing behavior?

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. The Uses and Gratification Theory

2.2. Theory of Planned Behaviour and Norm Activation Model

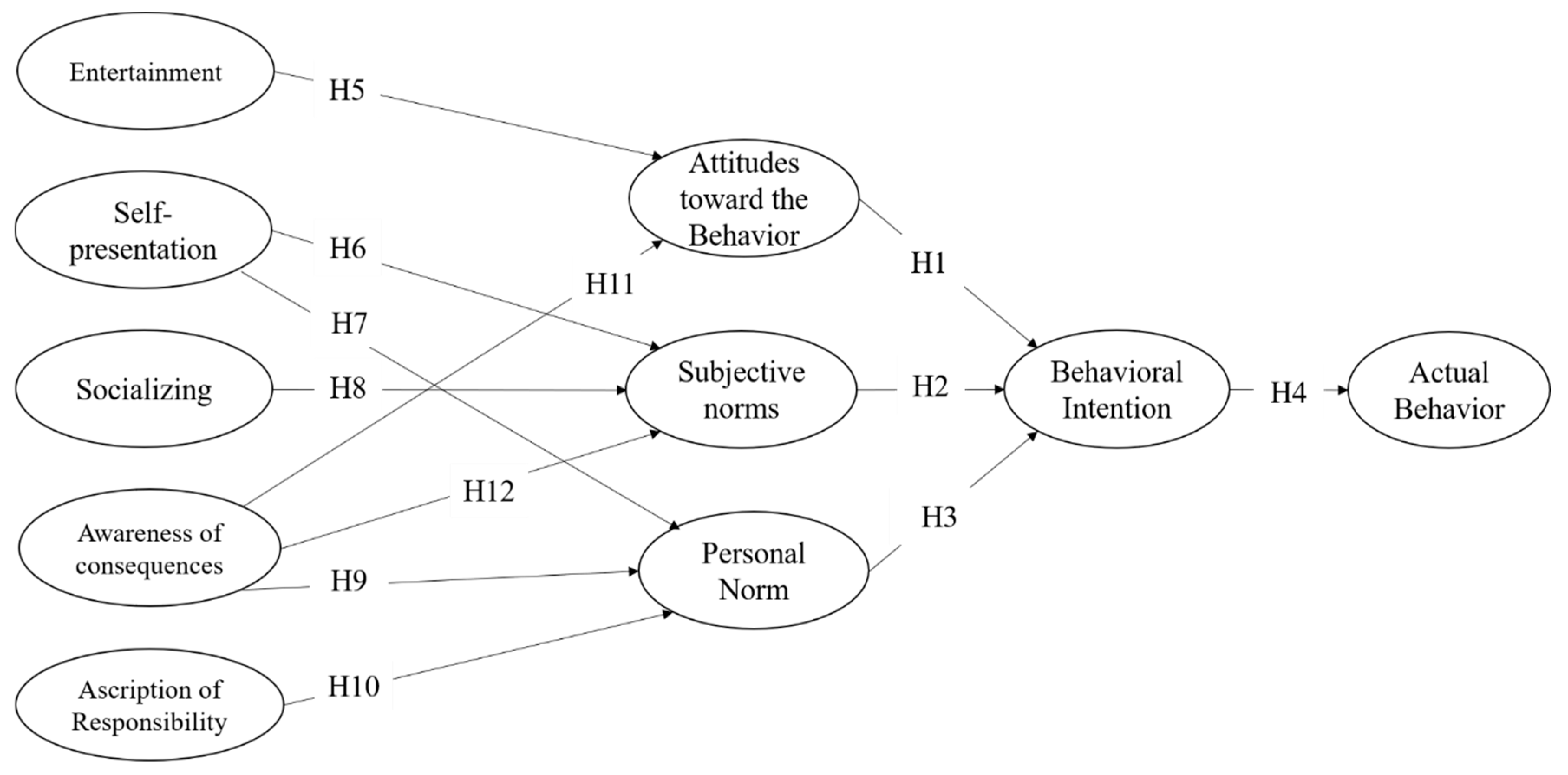

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Research Hypotheses

3.2.1. Formation of the Behavior

3.2.2. Egoistic Motivations

3.2.3. Altruistic Motivations

4. Research Methods

4.1. Measurement Instruments

4.2. Data Collection

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

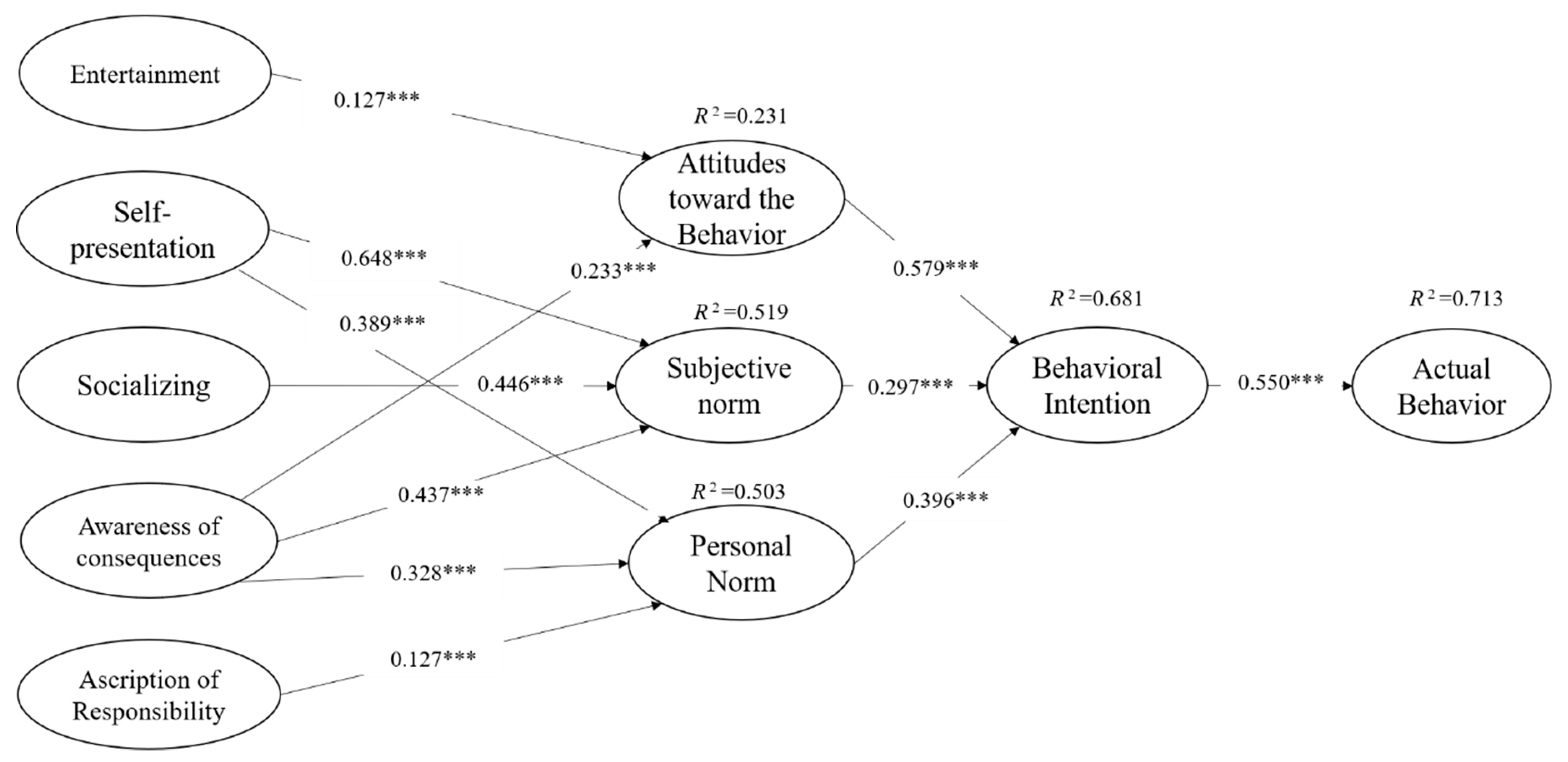

5.2. Structure Model Examination

5.3. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limiations and Future Work

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Measurement Items

- Entertainment (EN)Sharing environmental information on WeChatEN1: Is entertaining for me.EN2: Is funny for me.EN3: Is a pleasure for me.

- Self-presentation (SP)Sharing environmental information on WeChat, I want others to perceive me asSP1: Environmentally friendly.SP2: A pro-environmental person.SP3: An environment protector.

- Socializing (SO)Sharing environmental information on WeChat, I want toSO1: Get peer support from others.SO2: Feel like I belong to a community.SO3: Talk about something with others

- Awareness of ConsequencesSharing environmental information on WeChat is beneficial toAC1: Remind the public of environmental issues.AC2: Awaken people’s awareness of environmental protection.AC3: Promote pro-environmental behavior among the public.

- Ascription of ResponsibilityEvery one of usAR1: Is responsible for helping spread environment-related news.AR2: Has the responsibility to help promote pro-environmental ideas.AR3: Should make efforts to participate in environmental information dissemination.

- Attitudes Toward the BehaviorFor me, sharing environmental information on WeChat isAT1: Bad (1)–Good (5).AT2: Foolish (1)–Wise (5).AT4: Harmful (1)–Beneficial (5).

- Subjective NormSN1: My friends think I should share environmental information on WeChat.SN2: My family would want me to share environmental information on WeChat.SN3: People who are important to me expect me to share environmental information on WeChat.

- Personal normPN1: I feel morally obliged to share environmental news on WeChat.PN2: I feel personally obliged to share my pro-environmental behavior on WeChat.PN3: I feel that I have the responsibility to share my environmentally friendly lifestyle on WeChat.

- Behavioral IntentionBI1: I am willing to post environment-related information on my Moment of WeChat.BI2: I will share environmentally friendly suggestions with others on WeChat.BI3: I would like to let others know about my pro-environmental behavior through WeChat.

- Actual BehaviorBI1: I have posted environmental related information on my Moment of WeChat.BI2: I have shared environment-friendly suggestions with others on WeChat.BI3: I have let others know about my pro-environmental behavior through WeChat.

References

- Byrum, K. “Hey Friend, Buy Green”: Social Media Use to Influence Eco-Purchasing Involvement. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.; Lee, C.; Orth, U.; Kim, C.-H.; Kahle, L. Sustainable marketing and social media: A cross-country analysis of motives for sustainable behaviors. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K.; Yao, X. Air pollution in mega cities in China. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-P.; Cheng, X.-M. Energy consumption, carbon emissions, and economic growth in China. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2706–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozov, E. The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom by Evgeny Morozov; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fatkin, J.-M.; Lansdown, T.C. Prosocial media in action. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W. City clusters in China: Air and surface water pollution. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 4, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Yang, L. A review of heavy metal contaminations in urban soils, urban road dusts and agricultural soils from China. Microchem. J. 2010, 94, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.W.-H.; Fryxell, G.E. Governmental and societal support for environmental enforcement in China: An empirical study in Guangzhou. J. Dev. Stud. 2005, 41, 558–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencent. WeChat Annual Data Report; Tencent: Shenzhen, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, C.-H.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, X. Service quality, satisfaction, stickiness, and usage intentions: An exploratory evaluation in the context of WeChat services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yang, Y. An experimental study of Chinese tourists using a company-hosted WeChat official account. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 27, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Ge, S.; Kong, H.; Ning, H. An improved clustering algorithm and its application in Wechat sports users analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 129, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-H.S.; Men, R.L. Social messengers as the new frontier of organization-public engagement: A WeChat study. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Chai, S.; Lei, M.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lopez, V. Effects of using WeChat-assisted perioperative care instructions for parents of pediatric patients undergoing day surgery for herniorrhaphy. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan-Haase, A.; Young, A.L. Uses and gratifications of social media: A comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2010, 30, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQarni, Z.A.; Yunus, F.; Househ, M.S. Health information sharing on Facebook: An exploratory study on diabetes mellitus. J. Infect. Public Health 2016, 9, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talwar, S.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Zafar, N.; Alrasheedy, M. Why do people share fake news? Associations between the dark side of social media use and fake news sharing behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.K.; Ranzini, G. Click here to look clever: Self-presentation via selective sharing of music and film on social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 82, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Ahmad, N.; Zakaria, N.H. Social media for knowledge-sharing: A systematic literature review. Telemat. Inf. 2019, 37, 72–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yin, J.; Song, Y. An exploration of rumor combating behavior on social media in the context of social crises. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.A.; Maqbool, O.; Mushtaq, M.; Aljohani, N.R.; Daud, A.; Alowibdi, J.S.; Shahzad, B. Saving lives using social media: Analysis of the role of twitter for personal blood donation requests and dissemination. Telemat. Inf. 2018, 35, 892–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkitipong, L.; Chen, C.C.; Ractham, P. A community-based approach to sharing knowledge before, during, and after crisis events: A case study from Thailand. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibchurn, J.; Yan, X. Information disclosure on social networking sites: An intrinsic–extrinsic motivation perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Chen, G.M. College students’ disclosure of location-related information on Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, A.; Vitrano, J.; Gengo, N.J. Rationality-based beliefs affecting individual’s attitude and intention to use privacy controls on Facebook: An empirical investigation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 38, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; McCabe, S.; Wang, Y.; Chong, A.Y.L. Evaluating user-generated content in social media: An effective approach to encourage greater pro-environmental behavior in tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Utilization of mass communication by the individual. Uses Mass Commun. Curr. Perspect. Gratif. Res. 1974, 7, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, W.R.; Rosenberg, W.L. The 1985 Philadelphia newspaper strike: A uses and gratifications study. J. Q. 1987, 64, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, O.W.-Y.; Leung, L. Effects of gratification-opportunities and gratifications-obtained on preferences of instant messaging and e-mail among college students. Telemat. Inf. 2009, 26, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, L. The Gratification Niches of Personal E-mail and the Telephone. Commun. Res. 2000, 27, 227–248. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R.; Schkade, L.L. Determining uses and gratifications for the Internet. Decis. Sci. 2004, 35, 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phua, J.; Jin, S.V.; Kim, J.J. Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social capital: A comparison of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, Y. Facebook versus Instagram: How perceived gratifications and technological attributes are related to the change in social media usage. Soc. Sci. J. 2019, 56, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Wang, W. Uses and gratifications of social media: A comparison of microblog and WeChat. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2015, 17, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Li, H. Understanding the effects of gratifications on the continuance intention to use WeChat in China: A perspective on uses and gratifications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Heikkilä, J.; Van Der Heijden, H. Modeling hedonic is continuance through the uses and gratifications theory: An empirical study in online games. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Ma, L. News sharing in social media: The effect of gratifications and prior experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J.; Jang, J.-W. Profiling good Samaritans in online knowledge forums: Effects of affiliative tendency, self-esteem, and public individuation on knowledge sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1336–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; Masood, A.; Ali, A. An SDT and TPB-based integrated approach to explore the role of autonomous and controlled motivations in “SNS discontinuance intention”. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Lee, J.-A.; Sung, Y.; Choi, S.M. Predicting selfie-posting behavior on social networking sites: An extension of theory of planned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.; Kitching, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The IT way of loafing in class: Extending the theory of planned behavior (TPB) to understand students’ cyberslacking intentions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng-Peprah, M.; de Vries, N.; Acheampong, M. Households’ willingness to adopt greywater treatment technologies in a developing country—Exploring a modified theory of planned behaviour (TPB) model including personal norm. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 254, 109807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sujata, M.; Khor, K.-S.; Ramayah, T.; Teoh, A.P. The role of social media on recycling behaviour. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. Explanations of the moderating effect of responsibility denial on the personal norm-behavior relationship. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1980, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A. Altruism and market-like behavior: An analysis of willingness to pay for recycled paper products. Popul. Environ. 2001, 22, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Antecedents of employee electricity saving behavior in organizations: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolekofski, K.E., Jr.; Heminger, A.R. Beliefs and attitudes affecting intentions to share information in an organizational setting. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daems, K.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Moons, I. The effect of ad integration and interactivity on young teenagers’ memory, brand attitude and personal data sharing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 99, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiddett, R.; Hunter, I.; Engelbrecht, J.; Handy, J. Patients’ attitudes towards sharing their health information. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2006, 75, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izuagbe, R.; Ifijeh, G.; Izuagbe-Roland, E.I.; Olawoyin, O.R.; Ogiamien, L.O. Determinants of perceived usefulness of social media in university libraries: Subjective norm, image and voluntariness as indicators. J. Acad. Libr. 2019, 45, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.-C.; Liu, C.-C.; Chen, K. The effects of hedonic/utilitarian expectations and social influence on continuance intention to play online games. Internet Res. 2014, 24, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.-K. The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Lee, K.-H.; Van Loo, M.F. Decisions to donate bone marrow: The role of attitudes and subjective norms across cultures. Psychol. Health 2001, 16, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Manstead, A.S.; Stradling, S.G. Extending the theory of planned behaviour: The role of personal norm. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 34, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanes, T. Personal norms in a globalized world: Norm-activation processes and reduced clothing consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhao, W.; Sun, X.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, R.; Qu, W. The effects of the self and social identity on the intention to microblog: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 754–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, F.; Hansstein, F.V. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, M.A.; Moula, M.M.E.; Seppälä, U. Results of intention-behaviour gap for solar energy in regular residential buildings in Finland. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Dhir, A.; Nieminen, M. Uses and gratifications of digital photo sharing on Facebook. Telemat. Inf. 2016, 33, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nov, O.; Naaman, M.; Ye, C. Analysis of participation in an online photo-sharing community: A multidimensional perspective. JASIS 2010, 61, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Anchor: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R.; Allen, A.B.; Terry, M.L. Managing social images in naturalistic versus laboratory settings: Implications for understanding and studying self-presentation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Mosquera, P.M.; Uskul, A.K.; Cross, S.E. The centrality of social image in social psychology. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Marcus, J. Students’ self-presentation on Facebook: An examination of personality and self-construal factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Nguyen, T.; Thorpe, A.; Ishizaka, A.; Chakhar, S.; Meech, L. Being seen to care: The relationship between self-presentation and contributions to online pro-social crowdfunding campaigns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 83, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.M. Perspect. Media Eff. 1986, 15, 281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. A normative decision-making model of altruism. Altruism Help. Behav. 1981, 6, 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, morality, or habit? Predicting students’ car use for university routes with the models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, K. Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Han, H. Intention to pay conventional-hotel prices at a green hotel–a modification of the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.; Kee, K.F.; Valenzuela, S. Being immersed in social networking environment: Facebook groups, uses and gratifications, and social outcomes. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Y.-C.; Chu, T.-H.; Tseng, C.-H. Gratifications for using CMC technologies: A comparison among SNS, IM, and e-mail. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, C.; Cai, D. Understanding WeChat users’ behavior of sharing social crisis information. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 34, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring instrument. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.E. The measurement of information systems effectiveness: Evaluating a measuring instrument. ACM SIGMIS Database Adv. Inf. Syst. 1995, 26, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.W.; Stone, R.W. A structural equation model of end-user satisfaction with a computer-based medical information system. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 1994, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Chai, L. What drives electronic commerce across cultures? Across-cultural empirical investigation of the theory of planned behavior. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2002, 3, 240–253. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.-R.; Ebesu Hubbard, A.S.; O’Riordan, C.K.; Kim, M.-S. Incorporating culture into the theory of planned behavior: Predicting smoking cessation intentions among college students. Asian J. Commun. 2006, 16, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, T.; Gold, T.B.; Guthrie, D.; Wank, D. Social Connections in China: Institutions, Culture, and the Changing Nature of Guanxi; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, M.; Meade, A.W.; Allred, C.M.; Pappalardo, G.; Stoughton, J.W. Careless response and attrition as sources of bias in online survey assessments of personality traits and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Items | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 241 | 45.82 |

| Female | 285 | 54.18 | |

| Age | <18 years | 2 | 0.38 |

| 18~25 years | 68 | 12.93 | |

| 26~30 years | 165 | 31.37 | |

| 31~40 years | 230 | 43.73 | |

| 41~50 years | 50 | 9.51 | |

| 51~60 years | 10 | 1.90 | |

| >60 years | 1 | 0.19 | |

| Education | Middle school or below | 35 | 6.65 |

| High school | 59 | 11.22 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 395 | 75.10 | |

| Master’s degree or above | 37 | 7.03 | |

| Time spent on WeChat | <1 h/day | 25 | 4.75 |

| 1~21 h/day | 164 | 31.18 | |

| 3~4 1 h/day | 212 | 40.30 | |

| 5~6 1 h/day | 47 | 8.94 | |

| >61 h/day | 78 | 14.83 |

| Construct | EN | SP | SO | AC | AR | AT | SN | PN | BI | CR | AVE | √AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.719 | 0.848 | 0.656 | 0.810 |

| SP | 0.545 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.732 | 0.748 | 0.714 | 0.845 |

| SO | 0.415 | 0.578 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.794 | 0.776 | 0.705 | 0.840 |

| AC | 0.589 | 0.603 | 0.612 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.706 | 0.816 | 0.537 | 0.733 |

| AR | 0.458 | 0.637 | 0.645 | 0.670 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.819 | 0.827 | 0.658 | 0.811 |

| AT | 0.347 | 0.648 | 0.624 | 0.549 | 0.681 | - | - | - | - | 0.722 | 0.862 | 0.604 | 0.777 |

| SN | 0.369 | 0.614 | 0.579 | 0.534 | 0.666 | 0.649 | - | - | - | 0.751 | 0.916 | 0.581 | 0.762 |

| PN | 0.457 | 0.634 | 0.657 | 0.698 | 0.634 | 0.641 | 0.623 | - | - | 0.827 | 0.874 | 0.618 | 0.786 |

| BI | 0.301 | 0.541 | 0.678 | 0.528 | 0.637 | 0.619 | 0.628 | 0.617 | - | 0.768 | 0.797 | 0.567 | 0.753 |

| AB | 0.397 | 0.628 | 0.649 | 0.617 | 0.684 | 0.572 | 0.662 | 0.675 | 0.697 | 0.815 | 0.838 | 0.735 | 0.857 |

| Dependent Variables | EN | SP | SO | AC | AR | AT | SN | PN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | 0.093 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.204 *** | 0.048 *** | - | - | - |

| AB | 0.030 *** | 0.421 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.301 *** | 0.057 *** | 0.319 *** | 0.107 *** | 0.201 *** |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y. An Investigation of the Influencing Factors of Chinese WeChat Users’ Environmental Information-Sharing Behavior Based on an Integrated Model of UGT, NAM, and TPB. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2710. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072710

Chen Y. An Investigation of the Influencing Factors of Chinese WeChat Users’ Environmental Information-Sharing Behavior Based on an Integrated Model of UGT, NAM, and TPB. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2710. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072710

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yang. 2020. "An Investigation of the Influencing Factors of Chinese WeChat Users’ Environmental Information-Sharing Behavior Based on an Integrated Model of UGT, NAM, and TPB" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2710. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072710

APA StyleChen, Y. (2020). An Investigation of the Influencing Factors of Chinese WeChat Users’ Environmental Information-Sharing Behavior Based on an Integrated Model of UGT, NAM, and TPB. Sustainability, 12(7), 2710. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072710