Microfinance Institutions Fostering Sustainable Development by Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Which are the main aspects related to MFI sustainability, researched by region?

- Which are the main Sustainability Indicators (SIs) reported by the MFIs worldwide?

- Which are the differences between regions on SI reporting?

- Which are the most important links and gaps between the main aspects reported by MFIs, and the main aspects studied by region?

2. Literature Review

- (1)

- When considering the individualistic-collectivistic dimension, microfinance research establishes a positive relationship in those societies more collectivist [40,41] and with higher levels of trust [41,42]. These circumstances are directly related to financial facts like considering self-help groups when granting funding, and in turn derived from social issues such as possible access to health services [43,44] or the consequences of this kind of repayment model, especially in the case of women [45,46]. This statement is contrasted to some extent with the individualism required for the entrepreneurship that seeks to promote microfinance. Thus, some authors suggest a change of policies to attend to this profile that incentivizes the involvement of the husband in the microenterprises run by women [47], tailor-made financing products and services according to the specific target, and investment in training and technical assistance that facilitates entrepreneurship [48].

- (2)

- The masculinity-femininity cultural dimension is also relevant; in this case, financial and social aspects emerge in studies that conclude that the cultural factors that influence the women’s experience should be analyzed and understood to establish the link between microfinance and gender inequality [45,49,50], intimate partner violence prevention [51] or access to health care [44].

- (3)

- The uncertainty avoidance dimension—that is, the regulation, controls and laws society needs to mitigate insecurity and ambiguity—in microfinance, become economic and governance consequences. Microfinance scholarly literature notes a reduction of the loan loss interest rates in countries where the MFIs’ financial performance is reported, where the institution is registered and follows regulations or laws [10], and where microfinance is an agricultural supporter [12] through products such as weather index-based insurance associated with agricultural lending to mitigate credit risk due to adverse situations [13].

- (4)

- The power distance cultural dimension indicates to what extent particular societies question or accept authority, and how strong the social hierarchy is. These will have financial and governance consequences and determine how microfinance activity should be managed. As shown in [52], it indicates that in rural Bangladesh, strict supervision over customers is needed to ensure that the funding received goes to productive programs [12], and that it should be considered how the hierarchical structure of an MFI should be designed to prevent it from being prone to corruption [13]. Cultures that value severe hierarchy are unlikely to have an entrepreneurial spirit [14]; therefore, it will have an adverse effect on the demand for financing products.

- (5)

- Time perspective orientation considers how inclined a society is to plan the future, or whether or not it tends to be present-oriented. Sustainability has a long-term orientation [8], while microfinance products tend to be designed for the short term. This means that microfinance, as is, cannot meet the needs of self-employed businesses seeking stable financing [12], and thus weakens longer-term adaptive capacity [13,14]. An important aspect connecting this cultural dimension with the FESG framework is the environment. Authors encouraging environmental behaviors link microfinance to long-term development, for its relation to gender equality [15] and to prevent the paradox of financing activities that endanger the health and livelihood of the receivers [16].

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

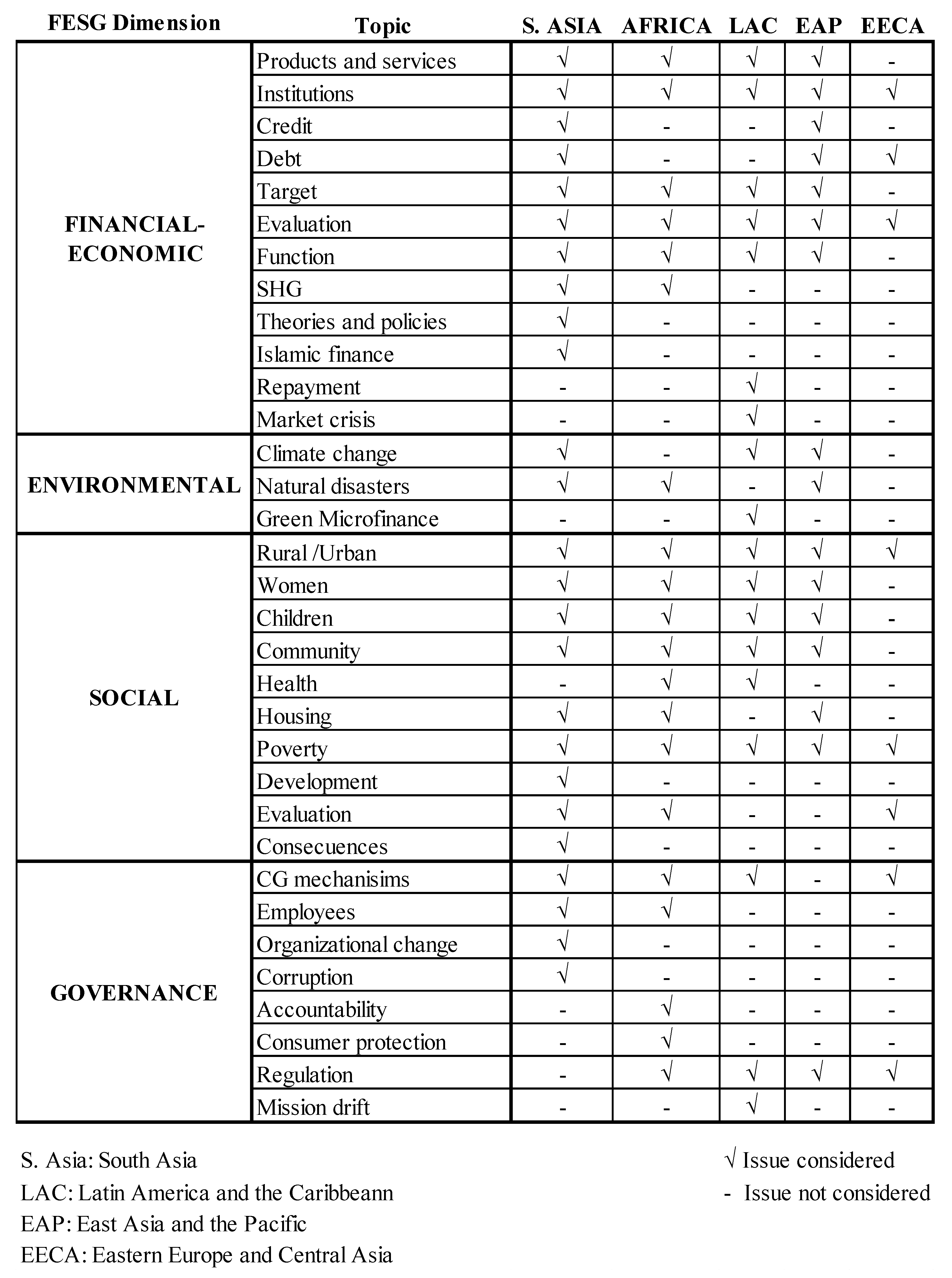

3.2.1. Paper Data Collection and Analysis of Keywords

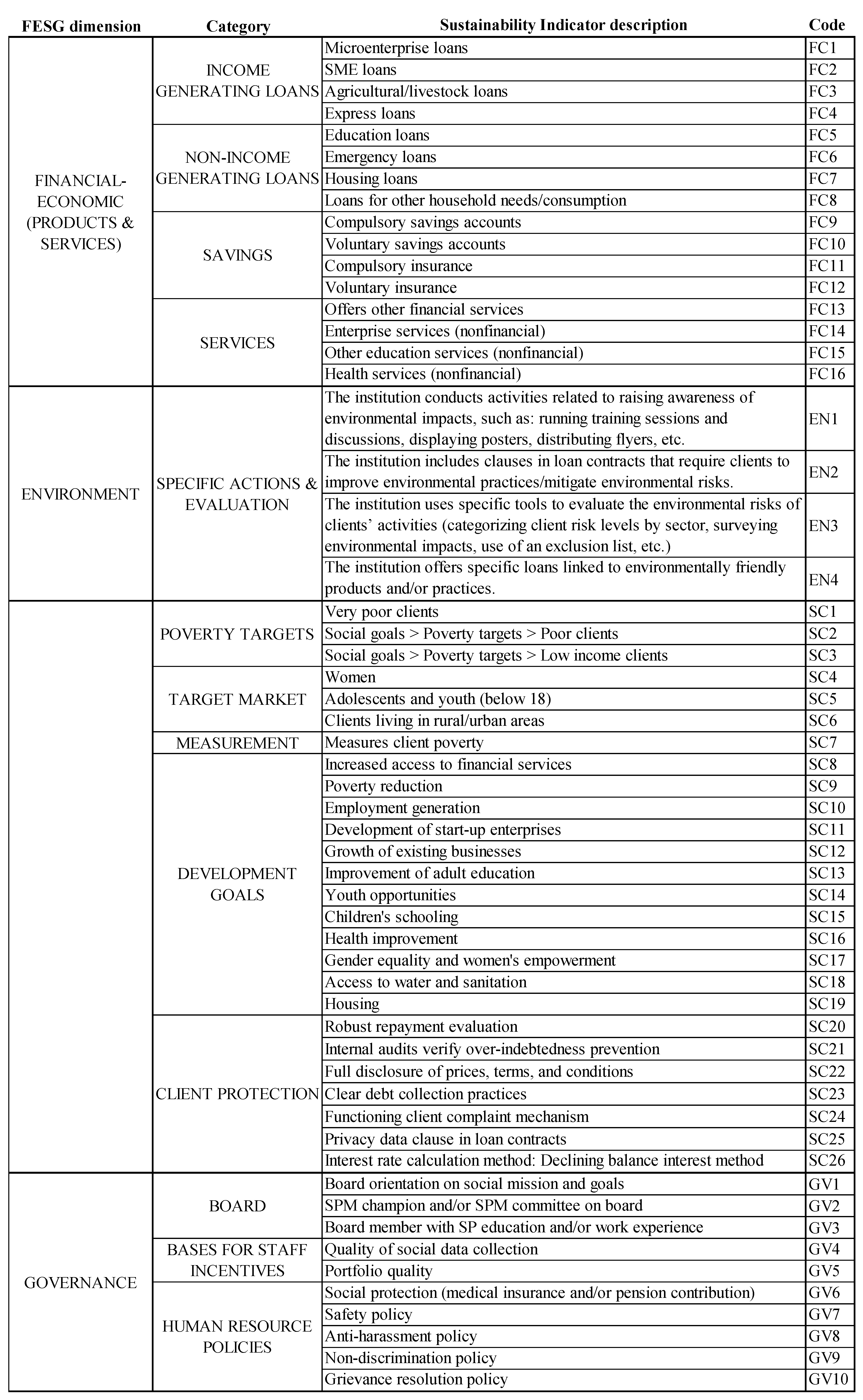

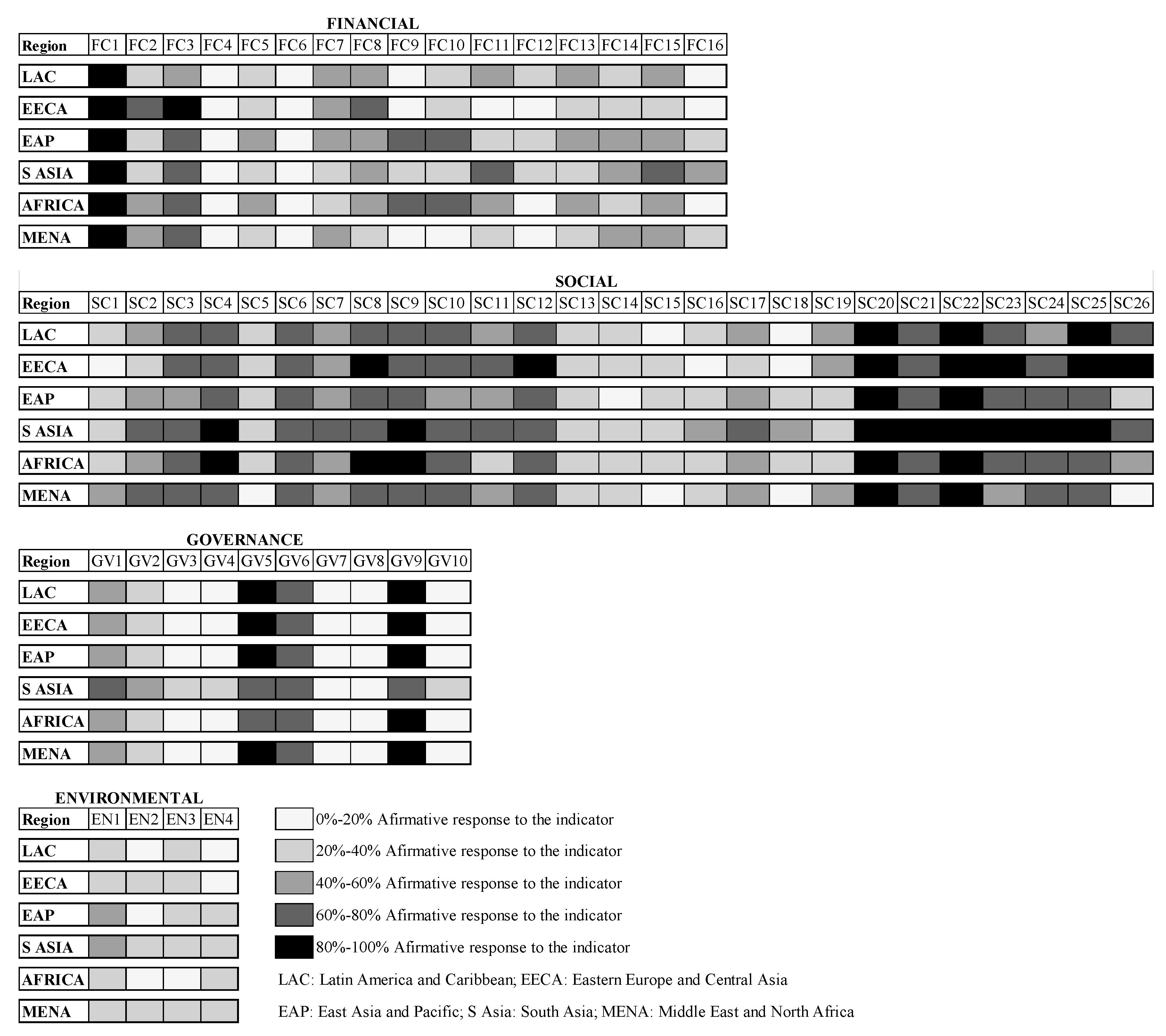

3.2.2. MIX Market Data Collection and Analysis of SIs

3.2.3. Combined Resources Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Findings From the Papers

4.2. Findings From the MIX Market

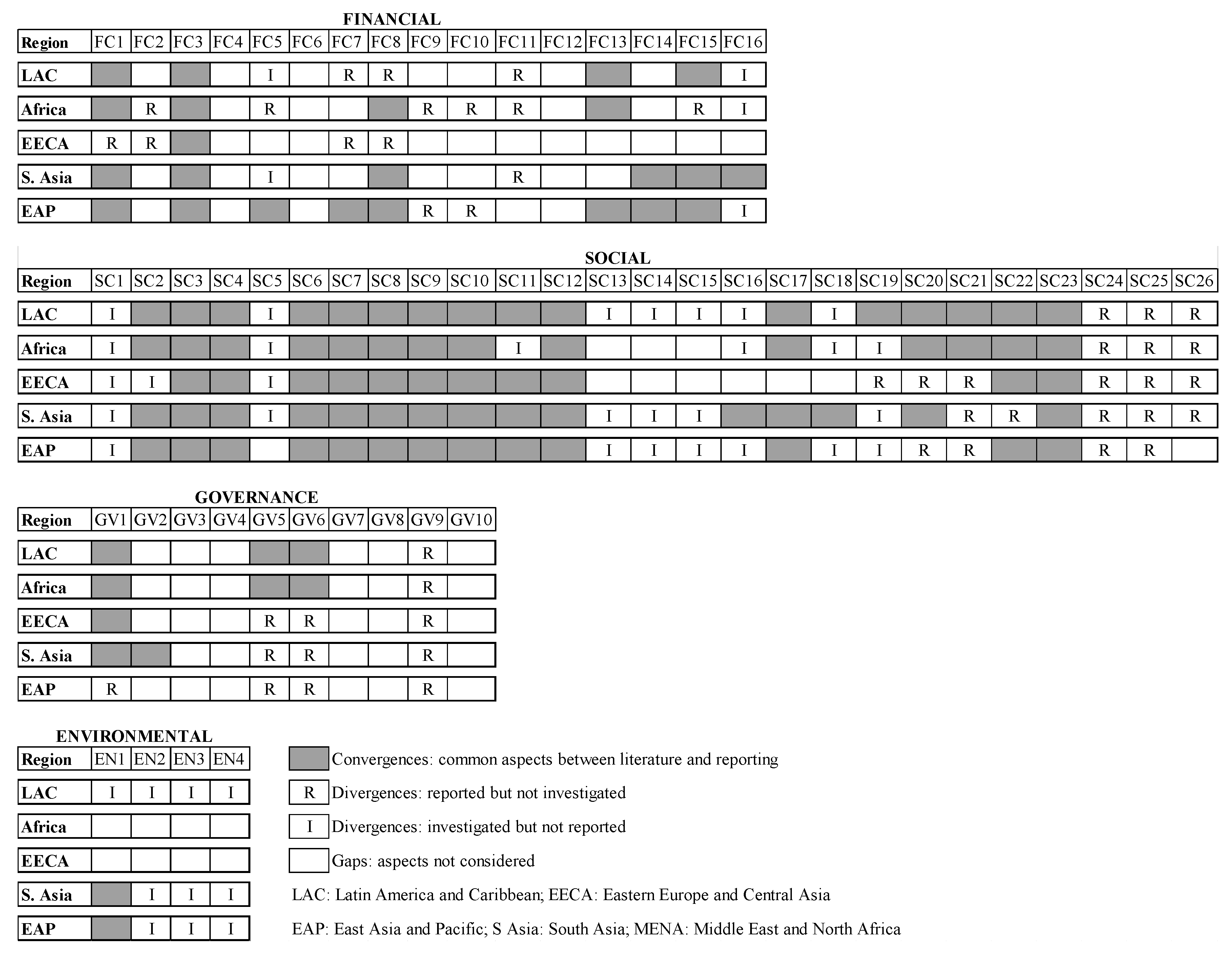

4.3. Findings Combining the Two Sources of Information

4.3.1. Convergences: Reported and Researched

4.3.2. Divergences

4.3.3. Gaps: Not Reported and Not Researched

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Convergences Barometers. Microfinance Barometer 2018; Convergences: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.K.; Sanchez, B.; Yu, J.S. Financial development and economic growth: New evidence from panel data. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2011, 51, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudon, M. Should access to credit be a right? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, I.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á. Microfinance institutions fostering sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H.; Khalid, S.; Agnelli, M.; Al-Athel, S.; Chidzero, B. Our common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable for Implications Development: And Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starik, M.; Kanashiro, P. Toward a Theory of Sustainability Management: Uncovering and Integrating the Nearly Obvious. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D. Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez, I.; Muñoz-Torres, M.-J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.-Á. Microfinance literature: A sustainability level perspective survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3382–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooyen, C.; Stewart, R.; de Wet, T. The Impact of Microfinance in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2249–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J.; Morduch, J. The Microfinance Promise. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1569–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S.R. Microfinance and poverty: Evidence using panel data from Bangladesh. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2005, 19, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamar, M. Global Outreach & Financial Performance Benchmark Report—2017–2018; Report prepared for MIX.; Microfinance Information Exchange: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: www.themix.org (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK; New Delhi, India, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Armendariz, B.; Szafarz, A. On mission drift in microfinance institutions. In The Handbook of Microfinance; World Scientific Publishing Co Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2011; pp. 341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Nieto, B.; Serrano-Cinca, C.; Molinero, C. Social efficiency in microfinance institutions. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2009, 60, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, G.R.; Jones-Christensen, L. Entrepreneurial value creation through green microfinance: Evidence from Asian microfinance lending criteria. Asian Bus. Manag. 2011, 10, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgerwood, J. Microfinance Handbook: An. Institutional and Financial Perspective; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Widiarto, I.; Emrouznejad, A.; Anastasakis, L. Observing choice of loan methods in not-for-profit microfinance using data envelopment analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 82, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, A.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Nykvist, B.; Lenton, T.M.; Crutzen, P.; Svedin, U.; et al. A safe operation space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Folke, C.; Gerten, D.; Reyers, B.; Persson, L.M.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission of Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke, T. ‘Greening’ gender equity: Microfinance and the sustainable development agenda. J. Econ. Issues 2015, 49, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersland, R.; Øystein Strøm, R. Performance and governance in microfinance institutions. J. Bank. Financ. 2009, 33, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartarska, V.; Nadolnyak, D. Do regulated microfinance institutions achieve better sustainability and outreach? Cross-country evidence. Appl. Econ. 2007, 39, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartarska, V. Governance and performance of microfinance institutions in Central and Eastern Europe and the newly independent states. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, A.; Krishnamoorthy, A. The Nexus Between Microfinance & Sustainable Development: Examining The Regulatory Changes Needed For Its Efficient Implementation. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 6, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarty, S.; Bass, A.E. Comparing Virtue, Consequentialist, and Deontological Ethics-Based Corporate Social Responsibility: Mitigating Microfinance Risk in Institutional Voids. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 487–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copestake, J.; Johnson, S.; Wright, K. Impact Assessment of Microfinance: Towards a New Protocol for Collection and Analysis of Qualitative Data. Work. Pap. 2002, 44, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rogaly, B. Micro-finance evangelism, ‘destitute women’, and the hard selling of a new anti-poverty formula. Dev. Pract. 1996, 6, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J. Microenterprise Occupation and Poverty Reduction in Microfinance Programs: Evidence from Sri Lanka. World Dev. 2004, 32, 1247–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, D.B. Beyond microfinance the VMSS way Beyond Microfinance. Indian J. Soc. Work 2015, 71, 551–576. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, A.K. Income Smoothing, Capital Management and Provisioning Behaviour of Microfinance Institutions: A Study Using Global Panel Data. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2017, 29, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, K.H.; Leatherman, S. Providing primary health care through integrated microfinance and health services in Latin America. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 132, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwale, J. Why Did I Not Prepare for This? The Politics of Negotiating Fieldwork Access, Identity, and Methodology in Researching Microfinance Institutions. Sage Open 2015, 5, 2158244015587560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Espallier, B.; Hudon, M.; Szafarz, A. Unsubsidized microfinance institutions. Econ. Lett. 2013, 120, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, A.U.; Tulla, A.F. Geography of rural enterprise banking and microfinance institutions in bangladesh. Doc. d’Analisi Geogr. 2015, 61, 325–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, P.; Kassim, S.; Adhi Kasari Sulung, L.; Iwani Surya Putri, N. Unique aspects of the Islamic microfinance financing process: Experience of Baitul Maal Wa Tamwil in Indonesia. Humanomics 2016, 32, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzynska, K.; Berggren, O. The Impact of Social Beliefs on Microfinance Performance. J. Int. Dev. 2015, 27, 1074–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. Borrowing Money, Exchanging Relationships: Making Microfinance Fit into Local Lives in Kumaon, India. World Dev. 2017, 93, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S. Expanding health coverage in India: Role of microfinance-based self-help groups. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1321272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Szatkowski, L.; Sinha, R.; Yaron, G.; Fogarty, A.; Allen, S.; Smyth, A.R.; Choudhary, S. Feasibility and pilot study of the effects of microfinance on mortality and nutrition in children under five amongst the very poor in india: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniello, P. Banking the Unbanked: Women and Microfinance in India. Urbanities 2015, 5, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, G.B. How Effective is a Self-Help Group Led Microfinance Programme in Empowering Women? Evidence from Rural India. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2015, 50, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmadja, A.S.; Su, J.J.; Sharma, P. Examining the impact of microfinance on microenterprise performance (implications for women-owned microenterprises in Indonesia). Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2016, 43, 962–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J.A.G.; Ramalho, J.J.S.; Vidigal da Silva, J. Understanding the microenterprise sector to design a tailor-made microfinance policy for Cape Verde. Port. Econ. J. 2006, 5, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Posso, A. Microfinance and gender inequality: Cross-country evidence. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 24, 1494–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Jo, H. Microfinance Interest Rate Puzzle: Price Rationing or Panic Pricing? Asia-Pac. J. Financ. Stud. 2017, 46, 185–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.; Ferrari, G.; Watts, C.H.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Phetla, G.; Pronyk, P.M. Economic evaluation of a combined microfinance and gender training intervention for the prevention of intimate partner violence in rural South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2011, 26, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazumder, M.S.U. Role of Microfinance in Sustainable Development in Rural Bangladesh. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minani, I. Impact of Microfinance and Entrepreneurship on Poverty Alleviation: Does National Culture Matter? Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 5, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, O.R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities; Addison-Wesley (content analysis): Reading, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communication Research; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An. Introduction to its Methodology; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cull, R.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Does Regulatory Supervision Curtail Microfinance Profitability and Outreach? World Dev. 2011, 39, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakoute-Tchuigoua, H. Is there a difference in performance by the legal status of microfinance institutions? Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2010, 50, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, P.; Levine, D.I.; Moretti, E. Do microfinance programs help families insure consumption against illness? Health Econ. 2009, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashta, A.; Khan, S.; Otto, P. Does Microfinance cause or reduce suicides? Policy recommedations for reducing borrowers stress. Strateg. Chang. 2015, 24, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruskal, W.H.; Wallis, W.A. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1952, 47, 583–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holvoet, N. The Impact of Microfinance on Decision-Making. Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A. Indian Microfinance Institutions: Performance of Young and Old Institutions. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2015, 19, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Towards better embedding sustainability into companies’ systems: An analysis of voluntary corporate initiatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 25, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amersdorffer, F.; Buchenrieder, G.; Bokusheva, R.; Wolz, A. Efficiency in microfinance: Financial and social performance of agricultural credit cooperatives in Bulgaria. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2015, 66, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelka, N.; Musshoff, O.; Weber, R. Does weather matter? How rainfall affects credit risk in agricultural microfinance. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2015, 75, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.; Ahmed, A.D. The demand for credit, credit rationing and the role of microfinance: Evidence from poor rural counties of China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2014, 6, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, H.A.; Berhanu, W. How efficient are the ethiopian microfinance institutions in extending financial services to the poor? A comparison with the commercial Banks. Qual. Quant. 2015, 51, 112–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, R.; Wahyudin, U.; Ardiwinata, J.S.; Abdu, W.J. Education and microfinance: An alternative approach to the empowerment of the poor people in Indonesia. Springerplus 2015, 4, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, M.A.J.; Masood, S.; Nasir, M. Impact of microfinance on the non-monetary aspects of poverty: Evidence from Pakistan. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lønborg, J.H.; Rasmussen, O.D. Can. Microfinance Reach the Poorest: Evidence from a Community-Managed Microfinance Intervention. World Dev. 2014, 64, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrin, S.; Baskaran, A.; Rasiah, R. Microfinance and savings among the poor: Evidence from Bangladesh microfinance sector. Qual. Quant. 2017, 51, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voola, A. Gendered poverty and education: Moving beyond access to expanding freedoms through microfinance policy in India and Australia. Int. Educ. J. 2016, 15, 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, F. Microfinance, Financial Literacy, and Household Power Configuration in Rural Bangladesh: An Empirical Study on Some Credit Borrowers. Voluntas 2015, 26, 1100–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S.J. Microfinance services, poverty and artisanial mineworkers in Africa: In search of measures for empowering vulnerable groups. J. Int. Dev. 2012, 24, 485–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpalu, W.; Alnaa, S.E.; Aglobitse, P.B. Access to microfinance and intra household business decision making: Implication for efficiency of female owned enterprises in Ghana. J. Socio. Econ. 2012, 41, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, G. Does Microfinance Enhance Gender Equity in Access to Finance? Evidence from Pakistan. Fem. Econ. 2017, 23, 160–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbola, F.W.; Acupan, A.; Mahmood, A. Does microfinance reduce poverty? New evidence from Northeastern Mindanao, the Philippines. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 50, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meador, J.; Fritz, A. Food security in rural Uganda: Assessing latent effects of microfinance on pre-participation. Dev. Pract. 2017, 27, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrove, M. A tale of three cities. Am. City Cty. 2017, 132, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Xiang, C.; Huang, J. Microfinance, self-employment, and entrepreneurs in less developed areas of rural china. China Econ. Rev. 2013, 27, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. Freedom from poverty is not for free’: Rural development and the microfinance crisis in Andhra Pradesh, India. J. Agrar. Chang. 2011, 11, 484–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. The antinomies of ‘financial inclusion’: Debt, distress and the workings of indian microfinance. J. Agrar. Chang. 2012, 12, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P. Debt, Uneven Development and Capitalist Crisis in South Africa. Backgr. Pap. Rosa Luxembg. Stift. Work. 2012, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Thrikawala, S.; Locke, S.; Reddy, K. Board structure-performance relationship in microfinance institutions (MFIs) in an emerging economy. Corp. Gov. 2016, 16, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassem, B.S. Governance and performance of microfinance institutions in Mediterranean countries. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2009, 10, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoach, S.B.; Lamanna, E. Measuring the Impact of Microfinance on Child Health Outcomes in Indonesia. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1808–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.; Wang, L. Avoiding the perils and fulfilling the promises of microfinance: A closer examination of the educational outcomes of clients’ children in Nicaragua. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2011, 31, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.H.; Khan, M.A. Where do the poorest go to seek outpatient care in Bangladesh: Hospitals run by government or microfinance institutions? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalib, A.K. How effective is microfinance in reaching the poorest? Empirical evidence on programme outreach in rural Pakistan. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2013, 14, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, R.; Yang, F. The impact of microfinance on factors empowering women: Regional and Delivery Mechanisms in India’s SHG Programme. J. Dev. Studies 2016, 53, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissler, K.H.; Goldberg, J.; Leatherman, S. Using microfinance to facilitate household investment in sanitation in rural Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2016, 31, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.; Moser, R.M.B.; Gonzalez, L. Microfinance and climate change impacts: The case of agroamigo in Brazil. RAE Rev. Adm. Empres. 2015, 55, 397–407. [Google Scholar]

- Mobin, M.A.; Masih, M.; Alhabshi, S.O. Religion of Islam and Microfinance: Does It Make Any Difference? Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2017, 53, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; AAjija, S.R. The effectiveness of baitul maal wat tamwil in reducing poverty the case of indonesian islamic microfinance institution. Humanomics 2015, 31, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalan, G.R.E.; Srnec, K. The scenario of microfinance in Latin America against the international financial crisis. Agric. Econ. 2018, 56, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelgesang, U. Microfinance in times of crisis: The effects of competition, rising indebtedness, and economic crisis on repayment behavior. World Dev. 2003, 31, 2085–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; De Janvry, A.; McIntosh, C.; Sadoulet, E. Prompting microfinance borrowers to save: A field experiment from Guatemala. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2013, 62, 21–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, I.; Takama, T.; Pratiwi, L.; Soeprastowo, E. Role of microfinance to support agricultural climate change adaptations in Indonesia: Encouraging private sector participation in climate finance. Futur. Food J. Food Agric. Soc. 2016, 4, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, A.; Paavola, J.; Tallontire, A. The Role of Microfinance in Household Livelihood Adaptation in Satkhira District, Southwest Bangladesh. World Dev. 2017, 92, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M. Evaluation of contingent repayments in microfinance: Evidence from a natural disaster in bangladesh. Dev. Econ. 2012, 50, 116–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, L.; Kassim, N.; Sparling, T.; Buscher, D.; Yu, G.; Boothby, N. Assessing the impact of microfinance programming on children: An evaluation from post-tsunami Aceh. Disasters 2015, 39, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becchetti, L.; Castriota, S. Does Microfinance Work as a Recovery Tool After Disasters? Evidence from the 2004 Tsunami. World Dev. 2011, 39, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poston, A. Lessons from a microfinance recapitalisation programme. Disasters 2010, 34, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azim, M.I.; Sheng, K.; Barut, M. Combating corruption in a microfinance institution. Manag. Audit. J. 2017, 32, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanga, F.K. Microfinance accountability in Cameroon: A cure or a curse for poverty alleviation? J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2017, 13, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, L.; Andrew, J.; van der Laan, S. Tools of accountability: Protecting microfinance clients in South Africa? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 1344–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, N.; Siwale, J. Microfinance regulation and effective corporate governance in Nigeria and Zambia. Int. J. Law Manag. 2017, 59, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayayi, A.G. Credit risk assessment in the microfinance industry: An application to a selected group of Vietnamese microfinance institutions and an extension to East Asian and Pacific microfinance institutions Ayayi Credit Risk Assessment. Econ. Transit. 2012, 20, 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes, G.C.I.; Gonzalez, L.K.G. The financial vs. the social approach of microfinance. A comparative global analysis/El enfoque financiero vs. el enfoque social del microcredito. Un analisis comparativo mundial. REVESCO. Revista de Estudi. REVESCO. Rev. Estud. Coop. 2015, 118, 31–60. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Pérez, I.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J. Microfinance Institutions Fostering Sustainable Development by Region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072682

García-Pérez I, Fernández-Izquierdo MÁ, Muñoz-Torres MJ. Microfinance Institutions Fostering Sustainable Development by Region. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072682

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Pérez, Icíar, María Ángeles Fernández-Izquierdo, and María Jesús Muñoz-Torres. 2020. "Microfinance Institutions Fostering Sustainable Development by Region" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072682

APA StyleGarcía-Pérez, I., Fernández-Izquierdo, M. Á., & Muñoz-Torres, M. J. (2020). Microfinance Institutions Fostering Sustainable Development by Region. Sustainability, 12(7), 2682. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072682