Evaluating Innovation in European Rural Development Programmes: Application of the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Re-Framing Social Innovation in a Rural Development Context

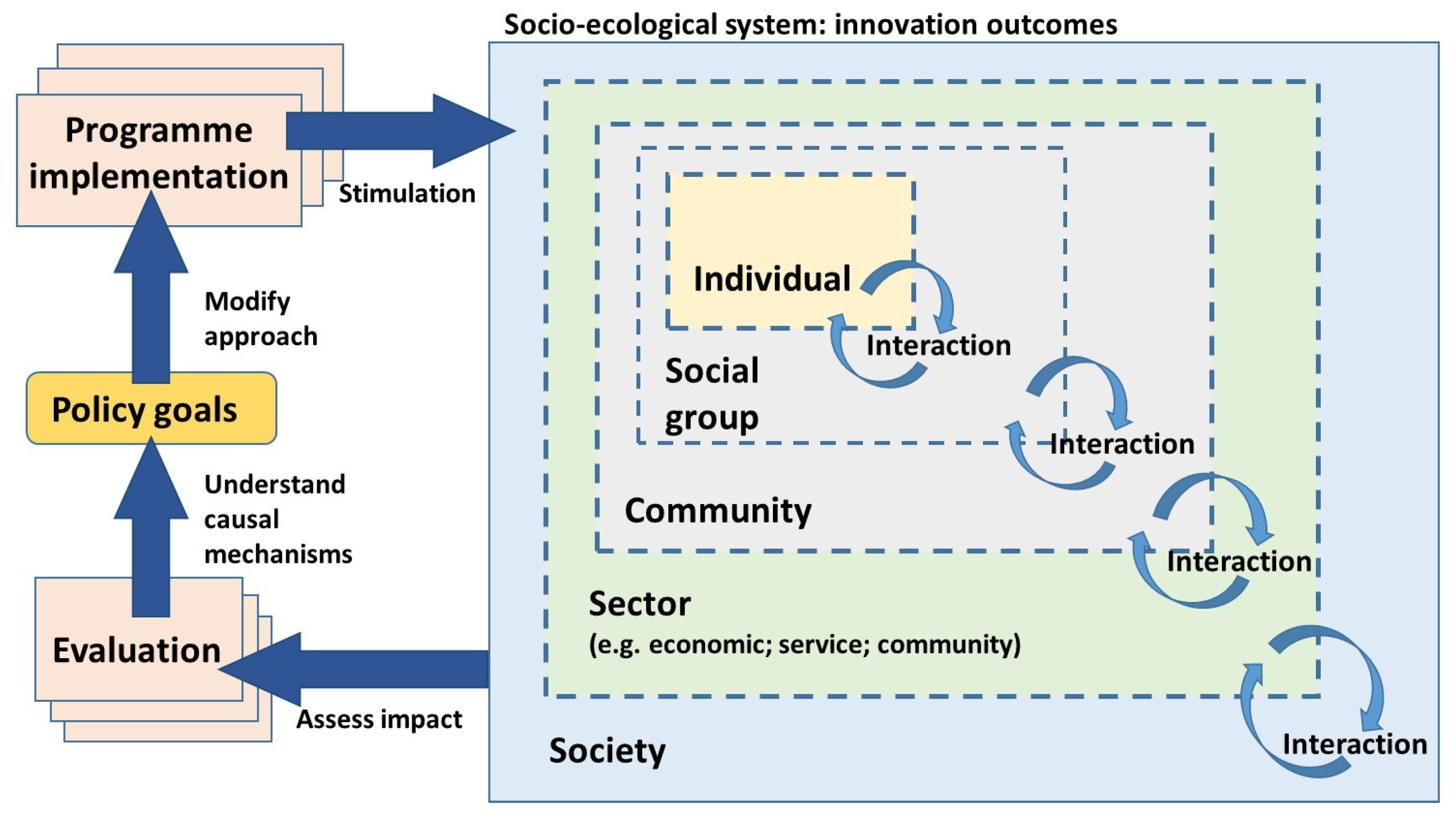

2.2. Evaluating ‘Social Innovation’ Processes within Rural Development

- Enterprise support: through improving the capacity of individuals in business and operational management to the point where they will be more receptive to change, and more comfortable with initiating change within their organisations;

- Technological change: through technological improvements that open up new business opportunities; capacity building through skills training;

- Service delivery: establishing new ways of organising (individuals, organisations, communities, society) or undertaking familiar activities; developing alternative approaches to making decisions and problem solving;

- Operational processes: initiating new ways of thinking about the relationship with the environment (for example, through concepts of sustainability and resilience) that cause systemic (or system-wide) change in attitudes, behaviour, and processes.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Programme Theory and Outcome Selection

3.2. Data Collection and Sampling

- Year project ended

- Project size (based on size of grant award)

- Location (geographic spread)

- Type of project (selected from the range within each Measure).

4. Results

4.1. Social Innovation Benefit Estimates from the SROI Model

- the ‘change score’, or indicator, used to assess the magnitude of impact of the programme on the outcome, modified by deadweight and attribution estimates that were determined through beneficiary and wider stakeholder interviews;

- financial approximations (or proxies) used to determine the value of change in the outcome;

- the present value of the outcome over the 5-year time horizon, informed by the financial proxy and the number of programme beneficiaries relevant to that outcome.

Social Innovation Outcomes

4.2. SROI Model Outputs

- Attribution of outcomes to the grant award

- Deadweight (what would have occurred without the programme grant award)

- Displacement (depending on the type of outcome)

- Annual drop-off in value (based on type of outcome)

- Careful selection of financial proxy values.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Axis | Measure Code | Measure Description | Scheme in England |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | 111 | Training | Vocational Training Scheme |

| 114 | Use of advisory services by farmers and forest holders | ||

| 115 | Setting up farm management, farm relief and farm/forest advisory services | Rural Enterprise Scheme (1. Setting up farm relief and farm management services) | |

| 121 | Investments in agricultural holdings | Energy Crops Scheme. Rural Enterprise Scheme (5i. Diversification into alternative-agricultural activities) | |

| 122 | Improving the economic value of forests | Woodland Grant Scheme | |

| 123 | Adding value to agricultural and forestry products | Processing and marketing grant | |

| 123 | Marketing of quality products | Rural Enterprise Scheme (2. Marketing of quality agricultural products) | |

| 124 | Cooperation for development of new products, processes and technologies | ||

| 125 | Agricultural water resources management | Rural Enterprise Scheme (6. Agricultural water resources management) | |

| 125 | Infrastructure related to the development and adaptation of agriculture and forestry | Rural Enterprise Scheme (7. Development and improvement of infrastructure connected with agricultural development) | |

| Axis 3 | 311 | Diversification of agricultural activities | Rural Enterprise Scheme (5ii. Diversification into non-agricultural activities) |

| 312 | Support for the creation and development of micro-enterprises | Rural Enterprise Scheme (8. Encouragement for tourist and craft activities) | |

| 313 | Encouragement for Tourism activities | Rural Enterprise Scheme (8. Encouragement for tourist and craft activities) | |

| 321 | Basic services for the rural economy and rural population | Rural Enterprise Scheme (3. Basic services for the rural economy and population) | |

| 322 | Renovation and development of villages | Rural Enterprise Scheme (4. Renovation and development of villages and protection and conservation of the rural heritage) | |

| 323 | Protection and conservation of rural heritage | Rural Enterprise Scheme (4. Renovation and development of villages and protection and conservation of the rural heritage) | |

| 331 | Training and information for economic actors in the fields covered by Axis 3 | ||

| 341 | Skills acquisition and animation with a view to preparing and implementing a local development strategy |

References

- Gifford, E.; McKelvey, M. Knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship and S3: Conceptualizing strategies for sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weresa, M.A. Strengthening the Knowledge Base for Innovation in the European Union; Polish Scientific Publishers PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Support to SMEs—Increasing Research and Innovation in SMEs and SME Development; Final Report Workpackage 2: Ex-post evaluation of Cohesion Policy Programmes 2007–2013, focussing on the ERDF and CF; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Evaluation of Innovation Activities: Guidance on Methods and Practices; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maye, D. Examining innovation from the bottom-up: An analysis of the permaculture community in England. Sociol. Rural. 2018, 58, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Common on Monitoring and Evaluation Framework for the Common Agricultural Policy; CAP Indicators European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, I.; Midmore, P. Models of rural development and approaches to analysis evaluation and decision-making. Économie Rural. Agric. Aliment. Territ. 2008, 307, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pelkmans, J.; Renda, A. Does EU Regulation Hinder or Stimulate Innovation? CEPS Special Report, No. 96; Centre for European Policy Studies: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. A Guide to Social Return on Investment; Cabinet Office: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Nicholls, K.; Racher, F. Investigating the health of rural communities: Toward framework development. Rural Remote Health 2004, 4, 244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harlock, J. Impact Measurement Practice in the UK Third Sector: A Review of Emerging Evidence; Working Paper 106; Third Sector Research Centre, University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.; Lawlor, E.; Neitzert, E.; Goodspeed, T. A Guide to Social Return on Investment: Update; The SROI Network: Liverpool, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo, R.; Rostagno, A.; Bonadonna, A. Land consolidation associations and the management of territories in harsh Italian environments: A review. Resources 2018, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Wittmayer, J.; Pel, B.; Weaver, P.; Dumitru, A.; Haxeltine, A.; Kemp, R.; Jørgensen, M.; Bauler, T.; Ruijsink, S.; et al. Transformative social innovation and (dis)empowerment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccarozzi, M. Does social innovation contribute to sustainability? The case of Italian innovative start-ups. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, R.; Kuhlmann, S. The rise of systemic instruments in innovation policy. Int. J. Foresight Innov. Policy IJFIP 2004, 1, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, P.; Boschma, R.; Crespo, J.; Rigby, D. Smart specialization policy in the European Union: Relatedness, knowledge complexity and regional diversification. Reg. Stud. 2019, 53, 1252–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foray, D. Smart specialisation strategies and industrial modernisation in European regions—Theory and practice. Camb. J. Econ. 2018, 42, 1505–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S. Why do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural development research?—Proposal for a stronger focus on social innovations in rural development research. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Making things happen: Social innovation and design. Design Issues 2014, 30, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preskill, H.; Beer, T. Evaluating Social Innovation. Center for Evaluation Innovation, 2012. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-preskill-beer.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2019).

- Moulaert, F.; Martinelli, F.; Swyngedouw, E.; Gonzalez, S. Towards alternative model(s) of local innovation. Urb. Stud. 2005, 42, 1969–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atterton, J.; Ward, N. Diversification and innovation in traditional land-based industries. In Rural Innovation; Mahroum, S., Atterton, J., Ward, N., Williams, A.M., Naylor, R., Hindle, R., Rowe, F., Eds.; NESTA: London, UK, 2007; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis, J. The myth of social capital in community development. Hous. Policy Debate 2001, 12, 781–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.; Burkett, I.; Braithwaite, K. Appreciating Assets; Carnegie UK Trust: Dunfermline, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, S.; Mehmood, A. Social innovation and the governance of sustainable places. Local Environ. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2015, 20, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, J.; Ilbery, B.; Maye, D.; Carey, J. Grassroots social innovation and food localisation: An investigation of the local food programme in England. Global Environ. Change 2013, 23, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, C.; Eren, H.; Halac, D.S. Social innovation and psychometric analysis. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 82, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Young Foundation. Social Innovation Overview: A Deliverable of the Project: “The Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Foundations for Building Social Innovation in Europe” (TEPSIE); 7th Framework Programme; DG Research, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pot, F.; Vaas, F. Social innovation, the new challenge for Europe. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2014, 57, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Have, R.P.; Rubalcaba, L. Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1925–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogburn, W. On Culture and Social Change: Selected Papers; Duncan, O.D., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn, J. Innovation and entrepreneurship: Schumpeter revisited. Ind. Corp. Change 1996, 5, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Aarts, N.; Leeuwis, C. Adaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: The interactions between innovation networks and their environment. Agric. Syst. 2010, 103, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, C.B.; Bregendahl, C. Collaborative community-supported agriculture: Balancing community capitals for producers and consumers. Int. J. Sociol. Agric. Food 2012, 19, 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Cajaba-Santana, G. Social innovation: Moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 82, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S. Social innovation in rural development: Identifying the key factors of success. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R. Rural social enterprises as embedded intermediaries: The innovative power of connecting rural communities with supra-regional networks. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Sanders, B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated; The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed.; New York Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Smart Specialisation Platform. Available online: https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Department for Business Innovation and Skills. Smart Specialisation in England. Submission to the European Commission, April 2015. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/436242/bis-15–310-smart-specialisation-in-england-submission-to-european-commission.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2020).

- Defra. Information on the axes and measures proposed for each axis, and their description. In The Rural Development Programme for England 2007–2013; Defra: London, UK, 2014; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, P.H.; Lipsey, M.W.; Freeman, H.E. Evaluation: A systematic Approach, 7th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Flockhart, A. Raising the profile of social enterprises: The use of social return on investment (SROI) and investment ready tools (IRT) to bridge the financial credibility gap. Soc. Enterp. J. 2005, 1, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Technical Handbook on the Monitoring and Evaluation Framework of the Common Agricultural Policy 2014–2020; Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, P.; Dattani, P. Social return on investment: Three technical challenges. Soc. Enterp. J. 2014, 10, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, R.; Hall, K. Social return on investment (SROI) and performance measurement. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Shifting the grounds: Constructivist grounded theory methods. In Grounded Theory: The Second Generation; Morse, J.M., Stern, P.N., Corbin, J., Bowers, B., Charmaz, K., Clarke, A.E., Eds.; Left Coast Press Inc.: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, A.J.; Johnston, L.H.; BrecFkon, J.D. Using QSR-NVivo to facilitate the development of a grounded theory project: An account of a worked example. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2010, 13, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.; Courtney, P. Conceptualising the wider societal outcomes of a community health programme and developing indicators for their measurement. Res. All 2018, 2, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Arcea, K.; Vanclaya, F. Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.; Bradley, D.; Hill, B. Towards an enhanced evaluation of European rural development policy reflections on United Kingdom experience. Économie Rural. Agric. Aliment. Territ. 2008; 307, 53–79. [Google Scholar]

| Programme Focus | Description of Social Innovation Outcomes at Various Scales | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual and Operational | Relational | System | |

| Enterprise support Technical and advisory support for operation and management Improving business skills Support for new products, services and adding value Support for financial services | Improvements in business confidence • Improved financial security • Efficiencies in management • Enhanced capacity to invest and take risks • Alter ‘traditional’ ways of doing | • Increased collaboration Catalytic—‘knock-on’ effects on other community activities Organisational learning Enhanced capacity to invest and take risks | • Increased collaboration Catalytic effects across area/region More efficient value chains Management efficiencies Enhanced capacity to invest Enhanced entrepreneurial skills |

| Technological change Supporting investment in production techniques Increasing technical skills Increasing environmental awareness to achieve resource efficiencies and reduced emissions | • Improved knowledge and skills • Efficiencies in energy and materials resource use • Cost reduction and higher productivity • New product development • Alter ‘traditional’ ways of doing | • Access to new technologies creates new opportunities Alter ‘traditional’ ways of doing Catalytic—‘knock-on’ effects across sector/community Improved environmental quality | • More highly skilled/productive workforce Efficiency improvements Catalytic effects across area/region Improved environmental quality |

| Service delivery Improving service delivery Targeting hard to reach sectors of society Addressing gaps in service delivery Increasing collaborative action Changing attitudes and behavior | • Enhanced confidence and well-being • New relationships and/or networks of activity • Increased levels of trust • Enhanced capacity to invest and take risks • Alter ‘traditional’ ways of doing | • Enhanced confidence and well-being Improved quality of life Organisational learning catalytic—‘knock-on’ effects across sector/community New relationships/networks of activity Increased levels of trust | • New relationships/networks Increased levels of trust More comprehensive service delivery Catalytic effects across area/region Community cohesion and increased participation |

| Operational processes Improving decision-making capabilities Improving delivery mechanisms Reducing implementation costs Enhancing adaptability and resilience | • Application of new techniques Enhanced capacity to take risks Increased levels of trust Wider utilisation of new technology Alter ‘traditional’ ways of doing | • Increased confidence in government support • Improved project selection (lower deadweight/displacement) Lower project failure rate Organisational learning (how to do things) | • Improved project selection (lower deadweight/displacement) Lower project failure rate Organisational learning Enhanced local and regional outcomes Reduced delivery costs |

| Innovation Category | Outcome | Change Score (after Accounting for Deadweight and Attribution) | Financial Proxy | Proxy Value (£) per Unit/Year | Present Value (PV) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Increased confidence to apply for grants | 0.0758 | Percentage change in income required to enter/exit dairy industry (per person) | 1325 | £8,900,589 |

| Increased business confidence | 0.0678 | Cost of self-esteem course (per person) | 215 | £535,949 | |

| Enhanced capacity to resolve issues | 0.1019 | Cost of training course to improve business performance (per business) | 545 | £19,747,605 | |

| Generation of new business ideas | 0.1078 | Earnings differential realised by completing an HND/HNC qualification (per person) | 1950 | £10,603,391 | |

| Changes to soil and land management practices | 0.0342 | Estimated cost of soil erosion (per ha) | 2250 | £5,664,808 | |

| Operational | Improved competitiveness (livestock) | 0.0395 | Average agricultural gross margin for livestock farms (per farm) | 4617 | £7,354,250 |

| Improved wood product value | 0.0704 | Cost of agricultural consultant advice on business management (per business) | 1800 | £2,181,109 | |

| Improved business efficiency (woodland) | 0.0352 | Annual value of wood fuel from 1 ha of woodland (+30% premium for quality biomass) | 878.336 | £476,961 | |

| More effective woodland management | 0.0363 | Annual value of wood fuel from 1 ha of woodland (+30% premium for quality biomass) (per business) | 878.336 | £1,005,373 | |

| Improved viability of farm/business through increased scale and/or capacity | 0.0926 | Value of increased and safeguarded sales for agriculture/forestry through LEADER (per business) | 1243 | £4,129,867 | |

| More efficient management of on-farm resources | 0.0793 | Total input (variable) costs per farm in England (per business) | 9494 | £17,355,741 | |

| Improvement of farm product quality | 0.1113 | Added value from investing in precision agriculture (per business) | 1100 | £9,053,799 | |

| Reduced disease costs and improved animal performance | 0.0298 | Average cost of a Bovine Tuberculosis (bTB) breakdown borne by the farm (per business) | 14,000 | £5,198,123 | |

| Increase in farm action to reduce water pollution | 0.0481 | Average grant for tackling diffuse pollution on farms (per business) | 7300 | £6,962,889 | |

| Relational | Farm benefits from partnership building | 0.0184 | DfT estimation of business time savings (per business) | 7352.64 | £26,333,184 |

| Increased level of engagement across farming community | 0.0303 | Improvement in knowledge and skills from taking a part-time course (per person) | 847 | £1,736,779 | |

| Improved wood fuel supply chain capacity | 0.0234 | Annual value of wood fuel from 1 ha of woodland (per business) | 777.004 | £119,183 | |

| Opening up of new markets | 0.1038 | Cost of membership to CLA (per business) | 437 | £5,263,580 | |

| System | Woodland owners better informed | 0.0513 | Cost of agricultural consultant advice on farm management (per woodland owner) | 1800 | £3,398,616 |

| Improved biodiversity and management | 0.0469 | Household WTP for biodiversity value of woodland (per ha improved management) | 45 | £34,004,952 | |

| Total | £170,026,748 |

| Innovation Category | Outcome | Change Score (after Accounting for Deadweight and Attribution) | Financial Proxy | Proxy Value (£) per Unit/Year | Present Value (PV) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Creation/growth of new micro-enterprises | 0.1539 | Average cost of young person not in education, employment or training (per business) | 561.62 | £7,074,836.80 |

| Improved business capacity to resolve issues | 0.1557 | Cost of training course to improve business performance (per person) | 545 | £10,703,487.02 | |

| Improved well-being through development of cultural and recreational facilities | 0.1092 | WTP for keeping the body and mind active from taking a part-time course (per person) | 693 | £50,459,131.57 | |

| Increased skills and confidence of local leaders | 0.0541 | Cost of leadership management training course (per person) | 780 | £1,416,838.86 | |

| Operational | Improved viability of farm/business | 0.1189 | Value of increased sales (agriculture + forestry) through LEADER (per business) | 1243 | £8,629,471.90 |

| Increase in farm incomes through diversification | 0.1518 | Value of increased sales from diversification (per business) | 1099 | £4,529,684.62 | |

| Improvement in tourism service provision | 0.0821 | DfT estimation of business time savings (per tourism provider) | 7352.64 | £40,873,587.88 | |

| Improved performance of business including resource efficiency | 0.0803 | Utility bill savings through increased resource efficiency (per business) | 138 | £861,337.31 | |

| Relational | Increased collaboration between tourism providers | 0.1192 | Value of increased sales arising from tourism development through LEADER (per tourism provider) | 17,274 | £56,506,314.21 |

| Increase in collaborative and networking enterprises | 0.0949 | Improvement in knowledge and skills from taking a part-time course (per business) | 847 | £4,315,204.53 | |

| Increase in the creation and development of rural social enterprises | 0.1447 | Cost of leadership management training course (per social enterprise) | 780 | £3,728,856.17 | |

| Improved social capital, community ties and strengthened civic engagement | 0.1816 | Average volunteer hourly rate for England (per person) | 2891.2 | £29,324,584.51 | |

| Increased cross-community development and regeneration through integrated village initiatives | 0.0912 | Average spend on social activities (per person) | 167 | £16,150,834.97 | |

| System | Improved capacity for local solutions to local problems | 0.1293 | Cost of leadership management training course (per person) | 780 | £3,049,790.77 |

| Improved links between tourism businesses and local environmental and cultural assets (including food and drink) | 0.1433 | Tourism value of heritage | 34.8 | £450,072.74 | |

| Total | £238,074,034 |

| Category | Axis 1 | Axis 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Total programme benefits (Years 1–5) | £368,078,857 | £426,257,211 |

| Total social innovation benefits (Years 1–5) | £170,026,748 | £238,074,034 |

| Title of SROI Study | Scope/Type of Project | SROI Ratio | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Return on Investment: a new way to measure FLAG results. Cornwall and Isles of Scilly FLAG. 2016 https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/fpfis/cms/farnet/social-return-investment-new-way-measure-flag-results | To measure the impact of animation activities of a Fisheries LAG in Cornwall 2012 - 15 | 1: 5.45 euro (1: £4.87) | Limited information available on methodology. |

| Solway Borders and Eden LAG, Cumbria (Rose Regeneration evaluation) | Application across all SBE LAG Axis 3 projects | 1: 5.34 | No information on how SROI was applied; benefits appear to be measured over 5 years. Mostly focused on jobs and use of community centre. Application of project. SROI across all Axis 3 of the SBE Programme. 15% ‘leakage’ applied to overall benefits. |

| North York Moors Coasts and Hills LAG (Rose Regeneration, 2014) | SROI of 3 capital projects | Capital projects average across the LAG: 1: 9.86 | SROI analysis of three projects; also ‘suggests’ the average return rate for capital projects is estimated to be around £6.00. |

| Social Return on Investment (SROI) Analysis of the Greenlink. Central Scotland Forest Trust (CSFT) (Ea O’Neill, greenspace, Scotland, 2009) | The Greenlink - a 7 km cycle path creating a direct route from Strathclyde Country Park to Motherwell Town Centre. | SROI ratio based on total investment: 1: 7.63 | Programme of woodland management, conservation and community events are part of the project, developed in partnership with the communities along the route. Variable deadweight/attribution measures applied. NPV over 5 years; standard rate of drop-off = 15%, and discounted at 3.5%. |

| Evaluation of the impact and economic and social return on investment of Axis 1 and Axis 3 activities, RDPE 2007-13 (Ekos Final Report June 2015) | A partial (‘cut-down’) SROI model developed based on 32 projects from three Axis 3 measures: (M321), village renewal (M322), and conservation of rural heritage (M323). 28 of the projects delivered through LEADER. SROI values presented in 8 thematic groups. | Thematic group ratios range from 1: 1.21 (Cultural and heritage improvements) to 1: 15.01 (Broadband) Community halls 1: 3.40 Natural asset improvements 1: 8.13 Overall Axis 3 SROI ratios: 1: 5.85 for RDPE investment 1: 6.65 for total public + private investment. | Based on data collected from beneficiaries in workshop settings (153 beneficiaries attended, approx. 5 people from each project) where benefits, attribution, deadweight, and displacement were all agreed by participants. Each beneficiary limited to 2 outcomes. NPV values calculated over 2–3 years. (n + 2). |

| Category of Social Innovation Outcome | Social Innovation Outcome Categories as a Proportion of Social Innovation Benefits (%) | Social Innovation Outcomes as a Proportion of Total Benefits (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis 1 | Axis 3 | Axis 1 | Axis 3 | |

| Individual | 0.267 | 0.293 | 0.123 | 0.163 |

| Operational | 0.316 | 0.231 | 0.146 | 0.129 |

| Relational | 0.197 | 0.462 | 0.091 | 0.258 |

| System | 0.220 | 0.015 | 0.102 | 0.008 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.461 | 0.558 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Courtney, P.; Powell, J. Evaluating Innovation in European Rural Development Programmes: Application of the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Method. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072657

Courtney P, Powell J. Evaluating Innovation in European Rural Development Programmes: Application of the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Method. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072657

Chicago/Turabian StyleCourtney, Paul, and John Powell. 2020. "Evaluating Innovation in European Rural Development Programmes: Application of the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Method" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072657

APA StyleCourtney, P., & Powell, J. (2020). Evaluating Innovation in European Rural Development Programmes: Application of the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Method. Sustainability, 12(7), 2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072657