Knowledge Management and Performance Measurement Systems for SMEs’ Economic Sustainability

Abstract

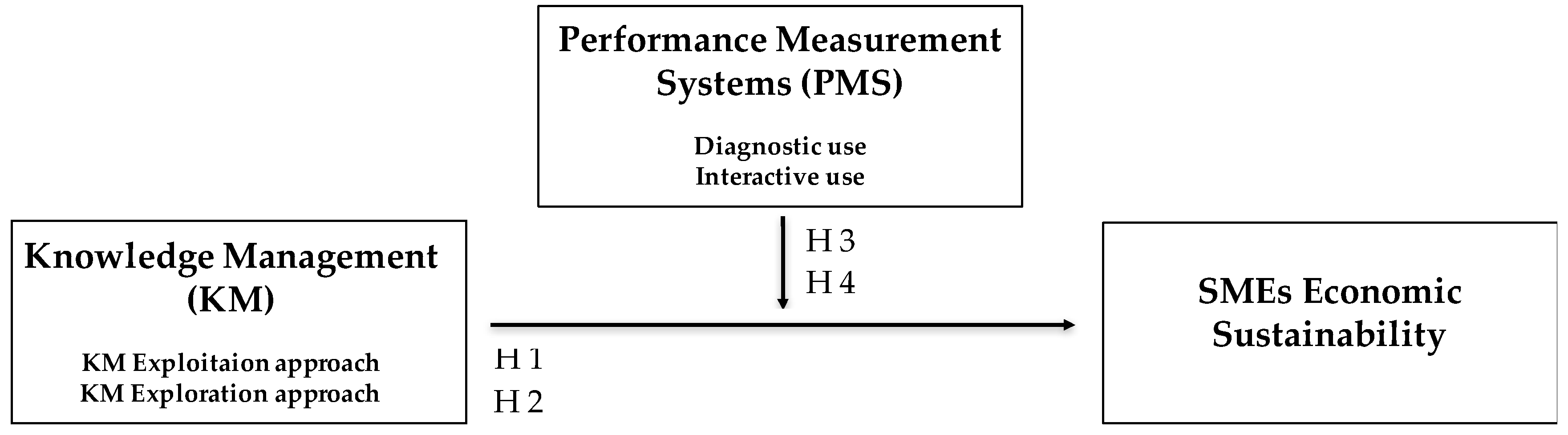

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Economic Sustainability in SMEs

- guarantee at any time cash-flow sufficient to ensure liquidity while producing a persistent above-average return to their shareholders (economic);

- add value to the communities within which they operate by increasing the human capital of individual partners as well as furthering the societal capital of these communities (social);

- use only natural resources that are consumed at a rate below the natural reproduction, or at a rate below the development of substitutes (environmental).

- small size of markets served;

- personal ownership and/or family management;

- financial and resources limitation;

- prevalence of personal relationships and informal business practices.

- owners and managers are more sensitive to financial and marketing issues and more focused on internal and business-related stakeholders (employees, customers, and suppliers) than external;

- for sustainability practices, the strategic processes maintain a strong dependence on personal values of the owner/manager and are influenced by profit maximization and family succession.

2.2. Knowledge Management (KM) for Economic Sustainability in SMEs

- business is not able to reach or maintain a sustainable level of economic profitability;

- strategic management and governance are interrupted by the death or retirement of the entrepreneur/owner; and

- operations efficiency and effectiveness suffer due to changes in personal motivation and aspirations of the key players.

- Exploitation strategies are related to knowledge storage, transfer, and application. They refer to the firms’ ability to enhance or refine exiting products or services exploiting existing knowledge to hone and extend the existing routines guaranteeing a greater efficiency within the organization supporting an increase of average performances [29]. Therefore, exploitation involves refinement, implementation, efficiency, production, and selection [27] pointing to more conservatism through stable revenues, maintaining key customers and efficiency for increasing the average performances [28].

- Exploration strategies are related to knowledge creation and are concerned with the development of new knowledge and experimentation, in order to foster changes and variations to support radical innovations. Therefore, it involves new breakthroughs, a “loose coupling” approach toward clients to explore new markets and products, and a lower strictness in relation to employees [29], seeking innovative opportunities which foster higher variations of performance [28]. In other words, exploration fits with research, breakthrough, experiments, risk-taking, and innovation [27].

2.2.1. KM Exploitation Approach in SMEs

2.2.2. KM Exploration Approach in SMEs

2.3. The Mediating Role of Performance Management Systems (PMSs) for KM and Economic Sustainability in SMEs

- Diagnostic use—the PMS is used to set standards, monitor organizational outcomes and correct deviations. In this case, the systems provide “the traditional feedback role as MCSs are used on an exception basis to monitor and reward the achievement of pre-established goals” [46];

- Interactive use—the PMS is able to promote adaptability and strategic dynamic relying on informal and continuous dialogue at different levels of organization. In this case, the process of measurement is able to “focus organizational attention, stimulate dialogue and support the emergence of new strategies” [46].

2.3.1. Diagnostic Use of PMS in KM Exploitation Approach

2.3.2. Interactive Use of PMS in KM Exploitation Approach

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Strategy

3.2. Variables Description

3.2.1. Dependent Variable—Firm Performance

3.2.2. Independent Variable—Knowledge Strategies

3.2.3. Moderating Variable—Performance Measurement Systems Adoption

3.2.4. Control Variable

3.3. Statistical Analysis and Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- -

- Water transport (50);

- -

- Air transport (51);

- -

- Publishing activities (58);

- -

- Motion picture, video and television programme production, sound recording, and music publishing activities (59);

- -

- Programming and broadcasting activities (60);

- -

- Telecommunications (61);

- -

- Computer programming, consultancy, and related activities (62);

- -

- Information service activities (63);

- -

- Financial service activities, except insurance and pension funding (64);

- -

- Insurance, reinsurance, and pension funding, except compulsory social security (65);

- -

- Activities auxiliary to financial services and insurance activities (66);

- -

- Legal and accounting activities (69);

- -

- Activities of head offices; management consultancy activities (70);

- -

- Architectural and engineering activities; technical testing and analysis (71);

- -

- Scientific research and development (72);

- -

- Advertising and market research (73);

- -

- Other professional, scientific, and technical activities (74);

- -

- Veterinary activities (75);

- -

- Employment activities (78);

- -

- Security and investigation activities (80);

- -

- Public administration and defense; compulsory social security (84);

- -

- Education (85);

- -

- Human health activities (86); Residential care activities (87);

- -

- Social work activities without accommodation (88);

- -

- Creative, arts, and entertainment activities (90);

- -

- Libraries, archives, museums and other cultural activities (91);

- -

- Gambling and betting activities (92);

- -

- Sports activities and amusement and recreation activities (93).

References

- Isobe, T.; Makino, S.; Montgomery, D.B. Exploitation, Exploration, and Firm Performance: The Case of Small Manufacturing Firms in Japan; Research Collection Lee Kong Chian School Of Business: Singapore, 2014; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, S.; Dunphy, D.C.; Griffiths, A. Organizational Change for Corporate Sustainability, Understanding Organizational Change, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, H.S.; Anumba, C.J.; Carrillo, P.M.; Al-Ghassani, A.M. STEPS: A knowledge management maturity roadmap for corporate sustainability. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2006, 12, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Galpin, T.; Whittington, J.L. Sustainability leadership: From strategy to results. J. Bus. Strat. 2012, 33, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. How Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement Strategy Moderates the CSR–Financial Performance Relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1274–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizano, M.; Alfaro-Cortés, E.; Priego de la Cruz, A.M. Stakeholders and Long-Term Sustainability of SMEs. Who Really Matters in Crisis Contexts, and When. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torugsa, N.A.; O’Donohue, W.; Hecker, R. Proactive CSR: An Empirical Analysis of the Role of its Economic, Social and Environmental Dimensions on the Association between Capabilities and Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, R.J. Social and Environmental Performance at SMEs: Considering Motivations, Capabilities, and Instrumentalism. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Meeting of the OECD Council at Ministerial Level; OECD: Paris, French, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Egbu, C.O.; Hari, S.; Renukappa, S.H. Knowledge management for sustainable competitiveness in small and medium surveying practices. Struct. Surv. 2005, 23, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, J.C.; Chua, A. The peculiarities of knowledge management processes in SMEs: The case of Singapore. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pmi, quanto conta in Italia il 92% delle aziende attive sul territorio? Available online: Https://www.infodata.ilsole24ore.com/2019/07/10/40229/?refresh_ce=1 (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Rapporto sulla competitività dei settori produttivi, Istat, Roma, Edizione: 2018. Available online: https://www.istat.it/storage/settori-produttivi/2018/Rapporto-competitivita-2018.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Beijerse, R.P. Knowledge management in small and medium-sized companies: Knowledge management for entrepreneurs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2000, 4, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiola, I. Organizational Learning, Innovativeness and Financial Performance of Small And Medium Enterprises (Smes) In Nigeria. Eur. J. Business Manag. 2013, 5, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoni, A.; Dumay, J.; Palmaccio, M.; Celenza, D. Knowledge transfer in a start-up craft brewery. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 25, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, D.; Fassio, C. From new imported inputs to new exported products. Firm-level evidence from Sweden. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm: Knowledge-based Theory of the Firm. Manag. J Strat. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Sengupta, K.; Lapiedra, R. Knowledge management and innovation performance in a high-tech SMEs industry. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 31, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, M.J.; Sànchez de Pablo, J.D. The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.P.; Noel, T.W. The Impact of Knowledge Resources on New Venture Performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2009, 47, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulous, K.; Moorman, C. Tradeoffs in marketing exploitation and exploration strategies: The overlooked role of market orientation. Intern. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severgnini, E.; Vieira, V.A.; Cardoza Galdamez, E.V. The indirect effects of performance measurement system and organizational ambidexterity on performance. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1176–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Probst, G.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploitation and Exploration for Sustained Performance. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W. Exploitation-Exploration Tensions and Organizational Ambidexterity: Managing Paradoxes of Innovation. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Handley, K.; Bagnoli, C.; Dumay, J. Knowledge management in small and medium. Enterprises: A structured literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 258–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. How to deal with knowledge management misalignment: A taxonomy based on a 3D fuzzy methodology. J. Knowl. Manag 2018, 22, 538–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaei, K.; Jusoh, R.; Bontis, N. Intellectual capital and performance measurement systems in Iran. J. Intellect. Cap. 2018, 19, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, S.R. Knowledge Management: Tools and Techniques. J. Libr. Inf. Technol. 2009, 29, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, J. Knowledge Management in Small Firms. Knowl. Process Manag. 2001, 8, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speziale, M.-T.; Klovienė, L. The Relationship between Performance Measurement and Sustainability Reporting: A Literature Review. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 156, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Otley, D.T. The contingency theory of management accounting: Achievement and prognosis. In Readings in Accounting for Management Control; Emmanuel, C., Otley, D., Merchant, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Garengo, P.; Bititci, U. Towards a contingency approach to performance measurement: An empirical study in Scottish SMEs. Organ. Soc. 2007, 27, 802–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.Y.; Tan, L.P.; Lee, C.S.; Wong, W.P. Knowledge Management performance measurement: Measures, approaches, trends and future directions. Inf. Dev. 2015, 31, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavia López, O.; Hiebl, M.R.W. Management Accounting in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Current Knowledge and Avenues for Further Research. J. Manag. Acc. Res. 2015, 27, 81–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, M.; Mills, J.; Wilcox, M.; Neely, A.; Platts, K. Designing, implementing and updating performance measurement systems. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 20, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Otley, D. The design and use of performance management systems: An extended framework for analysis. Manag. Acc. Res. 2009, 20, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A.; Mills, J.; Platts, K.; Richards, H.; Gregory, M.; Bourne, M. Performance measurement system design: Developing and testing a process-based approach. Syst. Des. 2000, 27, 81–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R. Levers of Control: How Managers Use Innovative Control Systems to Drive Strategic Renewal; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, R. Performance Measurement and Control Systems for Implementing Strategies; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mårtensson, M. A critical review of knowledge management as a management tool. J. Knowl. Manag. 2000, 4, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F. Management control systems and strategy: A resource-based perspective. Acc. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 529–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aureli, S.; Cardoni, A.; Del Baldo, M.; Lombardi, R. Traditional management accounting tools in SMEs’ network. Do they foster partner dialogue and business innovation? Manag. Control 2019, 1, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, K.K. Are PMS meeting the measurement needs of BPM? A literature review. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2013, 19, 535–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Stettner, U.; Tushman, M.L. Exploration and Exploitation Within and Across Organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 109–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubatkin, M.H.; Simsek, Z.; Ling, Y.; Veiga, J.F. Ambidexterity and Performance in Small-to Medium-Sized Firms: The Pivotal Role of Top Management Team Behavioral Integration. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 646–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Gedajlovic, E.; Zhang, H. Unpacking Organizational Ambidexterity: Dimensions, Contingencies, and Synergistic Effects. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Smith, K.G.; Shalley, C.E. The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Thongpapanl, N.; Dimov, D. Contextual ambidexterity in SMEs: The roles of internal and external rivalry. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 42, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebode, D.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J. Managing innovation for sustainability. R&D Manag. 2012, 42, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.M.; Scavarda, A.; Hofmeister, L.F.; Thomé, A.M.T.; Vaccaro, G.L.R. An analysis of the interplay between organizational sustainability, knowledge management, and open innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.H.P.; Carpinetti, L.C.R. Analysis of the interplay between knowledge and performance management in industrial clusters. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2012, 10, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditillo, A. Ordine e Creatività nelle Imprese ad alta Intensità di Conoscenza; Pearson: Milano, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, D.S. Management control systems across different modes of innovation: Implications for firm performance. Manag. Acc. Res. 2015, 28, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiaei, K.; Bontis, N. Translating knowledge management into performance: The role of performance measurement systems. MRR Ahead Print 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bititci, U.; Garengo, P.; Dörfler, V.; Nudurupati, S. Performance Measurement: Challenges for Tomorrow: Performance Measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strat. Env. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, L.; Duffy, A.; Whitfield, R.I. The Sustainability Cycle and Loop: Models for a more unified understanding of sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 133, 232–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WWF. Sustainability in the Construction Business – A Case study. Corp. Environ. Strategy 2003, 8, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S. Sustainability as a driver for corporate economic success: Consequences for the development of sustainability management control. Soc. Econ. 2010, 33, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, S.; Yang, D.-H. Small and Medium Enterprises and the Relation between Social Performance and Financial Performance: Empirical Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.R.; Collins, E.; Pavlovich, K.; Arunachalam, M. Sustainability practices of SMEs: The case of NZ. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2006, 15, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourlakis, M.; Maglaras, G.; Aktas, E.; Gallear, D.; Fotopoulos, C. Firm size and sustainable performance in food supply chains: Insights from Greek SMEs. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 152, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günerergin, M.; Penbek, Ş.; Zaptçıoğlu, D. Exploring the Problems and Advantages of Turkish SMEs for Sustainability. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikelenboom, M.; de Jong, G. The impact of dynamic capabilities on the sustainability performance of SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Cosenz, F.; Marinković, M. Designing dynamic performance management systems to foster SME competitiveness according to a sustainable development perspective: Empirical evidences from a case-study. IJBPM 2015, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, H.; Chawan, A. Demystifying Knowledge Management in Indian Manufacturing SMEs. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 1724–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.K. A knowledge management model for SMEs in the knowledge-based economy. In Proceedings of the Entrepreneurship and Innovation in the Knowledge-based Economy: Challenges and Strategies, Taipei, China, 23–26 July 2002; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Matlay, H. Organisational learning in small learning organizations: An empirical overview. Educ. Train. 2000, 4, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, D.W.; Ang’wa, W.; Forster, R.; Heydon, G.; Richardson, J.S. Learning in smaller organizations. Learn. Organ. 1998, 5, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salojärvi, S.; Furu, P.; Sveiby, K. Knowledge management and growth in Finnish SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag 2005, 9, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Efficiency and effectiveness of knowledge management systems in SMEs. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornjak, M. Knowledge Management and Management Accounting. In Proceedings of the Conference Paper, Portorož, Slovenia, 25–27 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Runar Edvardsson, I. Knowledge management in SMEs: A literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 16, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwantner, S.; Hiebl, M.R.W. Management control systems and organizational ambidexterity. J. Manag. Control 2016, 27, 371–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E.; Sha, S. Exploration and exploitation in the development of more entrepreneurial universities: A twisting learning path model of ambidexterity. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 141, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, B.M.; Annansingh, F.; Eaglestone, B.; Wakefield, R. Knowledge management issues in knowledge-intensive SMEs. J. Doc. 2006, 62, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgidou, L.P.; Petridou, E. The effect of competence exploration and competence exploitation on strategic entrepreneurship. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2011, 23, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M. Knowledge management enablers and outcomes in the small-and-medium sized enterprises. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 840–858. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.; Carrasco, C.E.; Elguezabal, I.Z.; Bilbao, Z.E. Knowledge Management Practices in SME. Case study In Basque Country SME. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Industrial Management. XVI Congreso de Ingeniería de Organización, Vigo, Spain, 18–20 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shirokova, G.; Vega, G.; Sokolova, L. Performance of Russian SMEs: Exploration, exploitation and strategic entrepreneurship. Crit. Perspect Bus 2013, 9, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, R.; Güttel, W.H.; Nosella, A. Dynamic capabilities and the evolution of knowledge management projects in SMEs. IJTM 2012, 60, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starbuck, W.H. Learning by knowledge-intensive firms. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 713–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, A. Organizational learning: A road map to evaluate learning outcomes in knowledge intensive firms. Dev. Learn. Organ. 2015, 29, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Weir, M. Intellectual assets and small knowledge-intensive business service firms. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2012, 19, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.; Wales, W.; Shirokova, G. Entrepreneurial orientation in the emerging Russian regulatory context: The criticality of interpersonal relationships. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2016, 10, 359–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. Researching Entrepreneurship; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen, J.I.; Aasheim, K. Organizational innovation promoters and performance effects in small, knowledge-intensive firms. Entrep. Innov. 2010, 11, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Crick, D.; Young, S. Small Firm Internalization and Business Strategy. Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, C. Performance Management Systems. In Design, Diagnosis and Use; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall Robert, H. Management control systems design within its organizational context: Findings from contingency-based and research directions for the future. Acc. Organ. Soc. 2003, 28, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otley, D. The contingency theory of management accounting and control: 1980–2014. Manag. Acc. Res. 2016, 31, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, P.M.; Hartmann, F.G.H. Aligning performance measurement systems with strategy: The case of environmental strategy. Abacus 2009, 45, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R. Integrative strategic performance measurement systems, strategic alignment of manufacturing, learning and strategic outcomes: An exploratory study. Acc. Organ Soc. 2005, 30, 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfield-Smith, K. Strategic management accounting: How far have we come in 25 years? Acc. Audit Acc. J. 2008, 21, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brignall, S.; Ballantine, J. Strategic enterprise management systems: New directions from research. Manag. Account. Res. 2004, 15, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klovienė, L.; Speziale, M.-T. Is Performance Measurement System Going Towards Sustainability in SMEs? Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Aligning enterprise knowledge and knowledge management systems to improve efficiency and effectiveness performance: A three-dimensional Fuzzy-based decision support system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 91, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditillo, A. Dealing with uncertainty in knowledge-intensive firms: The role of management control systems as knowledge integration mechanisms. Account. Organ. Soc. 2004, 29, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, M.; Li, Y.; Sawabe, N.; Horii, S. Performance Measurement Systems for Managing Exploration/Exploitation Tensions within and between Organizational Levels. SSRN J. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, I.P.; Gordon, B.R. Achieving contextual ambidexterity in R&D organizations: A management control system approach. R&D Manag. 2011, 41, 240–258. [Google Scholar]

- Miraglia, R.A. Nuove tendenze nei sistemi di controllo e di misurazione delle performance. Manag. Control 2012, 2, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, C.Z.M.; Mohamed, R. The Effect of Management Control System on Performance Measurement System at Small Medium Hotel in Malaysia. IJTEF 2013, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Groen, B.A.C.; Van de Belt, M.; Wilderom, C.P.M. Enabling performance measurement in a small professional service firm. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2012, 61, 839–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddara, M.; Zach, O. ERP Systems in SMEs: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2011 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2011), Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2011; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, K.; Ploder, C. Balanced system for knowledge process management in SMEs. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2009, 22, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxiotis, K. Exploring the rationales for ERP and knowledge management integration in SMEs. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2009, 22, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gresty, M. What role do information systems play in the knowledge management activities of SMEs? Bus. Inf. Rev. 2013, 30, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, R.; Watson, J.; Woodliff, D. SME survey methodology: Response rates, data quality, and cost effectiveness. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 28, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, R. The validity of ROI as a measure of business performance. Am. Econ. Rev. 1987, 77, 470–478. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Dodd, J.L. Economic value added (EVA (TM)): An empirical examination of a new. Corporate performance measure. J. Manag. Issues 1997, 9, 318. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, G.L. Reward structure as a moderator of the relationship between extraversion and sales per performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T. Is green and profitable sustainable? Assessing the trade-off between economic and environmental aspects. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, V.H.; Efroymson, R.A.; Kline, K.L.; Langholtz, M.H.; Leiby, P.N.; Oladosu, G.A.; Davis, M.R.; Downing, M.E.; Hilliard, M.R. Indicators for assessing socioeconomic sustainability of bioenergy systems: A short list of practical measures. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 26, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sitkin, S.B.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Schroeder, R.G. Distinguishing control form learning in total quality management a contingency perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 537–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. Knowledge exploitation, knowledge exploration, and competency trap. Knowl. Process Manag. 2006, 13, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. The Pursuit of Organizational Intelligence; Blackwell Business: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marengo, L. Knowledge distribution and coordination in organizations: On some social aspects of the Exploitation vs. exploration trade-off. Revue Int. Systémique 1993, 7, 553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Marengo, L. Knowledge, Communication and Coordination in an Adaptive Model of the Firm; Mimeo: Rome, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, A.; Jaworski, B.J.; Ajith, K. MARKOR: A measure of market orientation. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wong, P. Exploration vs. exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Essentials of Psychological Testing, 3rd ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Bisbe, J.; Otley, D. The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2004, 29, 709–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisbe, J.; Malagueño, R. The choice of interactive control systems under different innovation management modes. Eur. Account. Rev. 2009, 18, 371–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenbosch, B. An empirical analysis of the association between the use of executive support systems and perceived organizational competitiveness. Account. Organ. Soc. 1999, 24, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Discarding variables in a principal component analysis. I: Artificial data. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C 1972, 21, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, D.R. Separating reliability and stability in test-retest correlation. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1969, 34, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.H.; Perreault, W.D., Jr. Collinearity, power, and interpretation of multiple regression analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.H.; Zailani, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Foroughi, B. Impacts of Environmental Factors on Waste, Energy, and Resource Management and Sustainable Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alda, M. Corporate sustainability and institutional shareholders: The pressure of social responsible pension funds on environmental firm practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Ando, N.; Nishikawa, H. Recruitment of local human resources and its effect on foreign subsidiaries in Japan. Manag. Res. Rev. 2019, 42, 1014–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, W.; Adebe, M.; Dadanlar, H. The effect of CEO civic engagement on corporate social and environmental performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 1054–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Audretsch, D.B.; Carlsson, B. The knowledge spill-over theory of entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2009, 32, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, D. The Process of Entrepreneurial Learning: A Conceptual Framework. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcìa-Àlvarez, M.T. Analysis of the effects of ICTs in knowledge management and innovation: The case of Zara Group. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaziulusoy, A.İ.; Boyle, C.; McDowall, R. System innovation for sustainability: A systemic double-flow scenario method for companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders Jones, L.J.; Linderman, K. Process management, innovation and efficiency performance: The moderating effect of competitive intensity. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2014, 20, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. AC: A Review, Reconceptualization, and Extension. AMR 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, R.D.; Larkey, P. Performance measurement–emerging issues and trends. In Business Performance Measurement-Theory and Practice–Cambridge; Neely, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstedt, E. Knowledge renewal and knowledge companies. In Uppsala papers in Economic History, Research Report No. 22; Uppsala Universitet: Uppsala, Sweden, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Widener, S.K. An empirical analysis of the levers of control framework. Acc. Organ. Soc. 2007, 32, 757–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Using the Balanced Scorecard as a Strategic Management System. Harvard Bus. Rev. 1996, 14, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Schlierer, H.-J.; Werner, A.; Signori, S.; Garriga, E.; von Weltzien Hoivik, H.; Van Rossem, A.; Fassin, Y. How Do European SME Owner–Managers Make Sense of ‘Stakeholder Management’?: Insights from a Cross-National Study. J. Bus Ethics 2012, 109, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A. Le sfide evolutive del Management Control tra relazioni strategiche, innovazione e discontinuità: A knowledge transfer matter? Manag. Control 2018, 1, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövstål, E.; Jontoft, A.-M. Tensions at the intersection of management control and innovation: A literature review. J. Manag. Control 2017, 28, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.W.; Tiessen, P. Performance measurement and managerial teams. Account. Organ. Soc. 1999, 24, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Steps | Criteria | Number of Identified Firms |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Medium companies in Italy | 50 < number of employees < 250; 10 million < annual value of turnover < 50 million or 10 million < annual value of total assets < 43 million | 11,293 |

| 2. Italian Firms | Firms headquartered in Italy | 1,239,971 |

| 3. Knowledge Intensive Firms | NACE Rev. 2 codes: 50; 51; 58; 59; 60; 61; 62; 63; 64; 65; 66; 69; 70; 71; 72; 73; 74; 75; 78; 80; 84; 85; 86; 87; 88; 90; 91; 92; 93 | 207,509 |

| Total | 1603 |

| Variables | Items | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| KM Exploitation Approach | ET_1 | 0.78 |

| ET_2 | ||

| ET_3 | ||

| ET_4 | ||

| ET_5 | ||

| ET_6 | ||

| ET_7 | ||

| ET_8 | ||

| KM Exploration Approach | EX_1 | 0.75 |

| EX_2 | ||

| EX_3 | ||

| EX_4 | ||

| EX_5 | ||

| EX_6 | ||

| EX_7 | ||

| EX_8 |

| Variables | Items | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic PMS | DIA_1 | 0.85 |

| DIA_2 | ||

| DIA_3 | ||

| DIA_4 | ||

| DIA_5 | ||

| DIA_6 | ||

| DIA_7 | ||

| DIA_8 | ||

| Interactive PMS | INT_1 | 0.88 |

| INT_2 | ||

| INT_3 | ||

| INT_4 | ||

| INT_5 | ||

| INT_6 | ||

| INT_7 | ||

| INT_8 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ROI | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2 ET | 0.22 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3 EX | 0.34 | 0.34 | 1.00 | |||||

| 4 DIA | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 1.00 | ||||

| 5 INT | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.77 | 1.00 | |||

| 6 DIA*ET | 0.39 | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 1.00 | ||

| 7 INT*EX | 0.60 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.32 | 1.00 | |

| 8 Sales | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.11 | −0.03 | 1.00 |

| Independent Variable | Model 1 (1) | Model 2 (2) | Model 3 (3) | Model 4 (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET | 0.2272 *** (0.0664) | 0.1553 * (0.0649) | ||

| EX | 0.3444 *** (0.0643) | 0.2638 *** (0.0541) | ||

| DIA | 0.0192 (0.0636) | |||

| INT | 0.0855 (0.0535) | |||

| DIA*ET | 0.3653 *** (0.0634) | |||

| INT*EX | 0.5849 *** (0.0507) | |||

| Cons | −0.0247 | −0.0331 | −0.0274 | −0.0288 |

| (0.0661) | (0.0637) | (0.0618) | (0.0502) | |

| Sales | 0.0361 | −0.0200 | 0.0721 | 0.0043 |

| (0.0664) | (0.0643) | (0.0624) | (0.0508) | |

| Observation | 219 | 219 | 219 | 219 |

| R2 | 0.0517 ** | 0.1174 *** | 0.1793 *** | 0.4569 *** |

| F | 5.89 | 14.37 | 11.69 | 45.01 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardoni, A.; Zanin, F.; Corazza, G.; Paradisi, A. Knowledge Management and Performance Measurement Systems for SMEs’ Economic Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072594

Cardoni A, Zanin F, Corazza G, Paradisi A. Knowledge Management and Performance Measurement Systems for SMEs’ Economic Sustainability. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072594

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardoni, Andrea, Filippo Zanin, Giulio Corazza, and Alessio Paradisi. 2020. "Knowledge Management and Performance Measurement Systems for SMEs’ Economic Sustainability" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072594

APA StyleCardoni, A., Zanin, F., Corazza, G., & Paradisi, A. (2020). Knowledge Management and Performance Measurement Systems for SMEs’ Economic Sustainability. Sustainability, 12(7), 2594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072594