Female Entrepreneurship: Can Cooperatives Contribute to Overcoming the Gender Gap? A Spanish First Step to Equality

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What factors influence women’s engagement in cooperatives?

- (2)

- What exogenous factors favour women’s cooperative entrepreneurship?

- (3)

- What are the links between women’s engagement in cooperatives and their (a) social and economic expectations and (b) individual needs?

- (4)

- What is the perceived value of cooperatives, in relation to female associates’ perceptions of (a) equality and (b) work-life reconciliation practices?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Cooperatives as Drivers of Entrepreneurship and Equality

2.2. Contextualization of the Research

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

3.2. Study 1

3.3. Study 2

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carrasco, I. Corporate social responsibility, values and cooperation. IAER 2007, 13, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Monzón, J.L. The social economy facing emerging economic concepts: Social innovation, social responsibility, collaborative economy, social enterprises and solidary economy. CIRIEC Esp. Rev. Econ. Públ. Soc. Coop. 2018, 93, 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, M.; Torres, T.; Farré, M. Demografía de las cooperativas en tiempos de crisis. CIRIEC Esp. Rev. Econ. Públ. Soc. Coop. 2018, 93, 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bastida, M.; Olveira, A. Emprendimiento cooperativo femenino. Factores de atracción en Senent, M.J. Equidad de género en la economía social y solidaria. Una propuesta pluridisciplinar y transnacional. Sustainability 2020, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, M.L.E. ¿Son las cooperativas más favorables a la presencia de mujeres en los consejos que otras entidades? REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2013, 110, 96–128. [Google Scholar]

- Levie, J. Immigration, in-migration, ethnicity and entrepreneurship in the United Kingdom. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 28, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levie, J.; Hart, M. Business and social entrepreneurs in the UK: Gender, context and commitment. IJGE 2011, 3, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markussen, S.; Røed, K. The gender gap in entrepreneurship–The role of peer effects. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 134, 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iffländer, V.; Sinell, A.; Schraudner, M. Does Gender Make a Difference? Gender Differences in the Motivations and Strategies of Female and Male Academic Entrepreneurs; Women’s Entrepreneurship in Europe: Multidimensional Research and Case Study Insights; Birkner, S., Ettl, K., Welter, F., Ebbers, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, V.; Van Praag, M. Mind the gap: The role of gender in entrepreneurial career choice and social influence by founders. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkiran, G.B. The support of women-work within cooperative enterprises: Sample of Turkey. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anthopoulou, T. Rural women in local agro-food production: Between entrepreneurial initiatives and family strategies: A case study in Greece. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D.; Earle, J.S.; Lup, D. What makes small firms grow? Finance, human capital, technical assistance, and the business environment in Romania. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2005, 54, 33–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Savall, T. The social economy in a context of austerity policies: The tension between political discourse and implemented policies in Spain. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2019, 30, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Foncea, M.; Marcuello, C. Las empresas sociales en España: Concepto y características. Gizarte Ekonomiaren Euskal. Aldizkaria Rev. Vasca Econ. Soc. 2014, 8, 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Lejarriaga, G.; Bel, P.; Martín, S. El emprendimiento colectivo como salida laboral de los jóvenes: Análisis del caso de las empresas de trabajo asociado. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2013, 112, 36–65. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Carrasco, M.; López, J.A.; Marín, L. Estrategias, estilos de dirección, compromiso de los trabajadores, responsabilidad social y desempeño de las pequeñas y medianas empresas de economía social de la región de Murcia. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2013, 111, 108–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, I. Las cooperativas de mujeres en España: ¿empoderamiento o perpetuación de roles de género? REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2019, 131, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.; Foss, L.; Ahl, H. Gender and entrepreneurship research: A review of methodological approaches. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICA (International Co-operative Alliance). Guidance Notes to the Co-operative Principles; ICA: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://www.ica.coop/en/cooperatives/cooperative-identity (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Monzón, J.L.; Chaves, R. Recent Evolution of the Social Economy in the European Union; European Economic and Social Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/publications-other-work/publications/recent-evolutions-social-economy-study (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Jaén García, M. Crisis económica y economía social. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2017, 126, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Melgarejo, Z.; Arcelus, F.J.; Simon, K. Measuring performance: Differences between capitalist and labour-owned enterprises. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2007, 34, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R. Las Políticas de Apoyo a Las Cooperativas de Trabajo Asociado y a Las Sociedades Laborales en España. In Las Empresas de Trabajo Asociado en España. Evolución Reciente y Perspectivas; Monzon, J.L., Ed.; Ciriec-España: Valencia, Spain, 2010; pp. 161–224. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón, J.L.; Chaves, R. The Social Economy in the European Union, European Economic and Social Committee; EESC: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/presentation-by-dr-mr-monzon.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. Duke University, Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship; CASE: Durham, NC, USA, 1998; Available online: http://www.redalmarza.cl/ing/pdf/TheMeaningofsocialEntrepreneurship.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Bornstein, D.S. How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Light, P. Reshaping Social Entrepreneurship. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2006, 4, 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Barnir, A. Starting technologically innovative ventures: Reasons, human capital, and gender. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnir, A.; Watson, W.; Hutchins, M. Mediation and moderated mediation in the relationship among role models, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial career intention, and gender. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 41, 270–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, A.; Gherardi, S.; Poggio, B. Doing gender, doing entrepreneurship: An ethnographic account of intertwined practices. Gend. Work Organ. 2004, 11, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, D.; Jennings, J. Gender and entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A learning perspective. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2014, 6, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkler, J.E.; Whittington, K.B.; Ku, M.C.; Davies, A.R. Gender and venture capital decision-making: The effects of technical background and social capital on entrepreneurial evaluations. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Ledoux, M.J.; Magnan, M. The informational contribution of social and environmental disclosures for investors. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1276–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F.; Smallbone, D. Institutional perspectives on entrepreneurial behaviour in challenging environments. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Dodd, S.D.; Jack, S.L. Entrepreneurship as connecting: Some implications for theorising and practice. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheadon, M.; Duval-Couetil, N. Token entrepreneurs: A review of gender, capital, and context in technology entrepreneurship. Entrep. Region. Dev. 2019, 31, 308–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koellinger, P.; Minniti, M.; Schade, C. Gender Differences in Entrepreneurial Propensity. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2013, 75, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langowitz, N.; Minniti, M. The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.; Sandner, P.; Spiegel, F. How do risk attitudes differ within the group of entrepreneurs? the role of motivation and procedural utility. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, M.L.E.; Castel, A.F.G.; Sanz, F.J.P. ¿Presentan las cooperativas contextos favorables para la igualdad de género? especial referencia a la provincia de Teruel. CIRIEC Esp. Rev. Econ. Públ. Soc. Coop. 2016, 88, 60–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas Bonet, M.A. Desigualdades de Género en el Mercado Laboral: Un Problema Actual; Departament d’Economia Aplicada, Universitat de les Illes Balears: Palma, Spain, 2004; Available online: http://dea.uib.es/digitalAssets/136/136587_w6.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2019).

- Ribas Bonet, M.A. Mujer y Trabajo en la Economía Social; Consejo Económico y Social: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Senent, M.J. Principios Cooperativos, Equidad de Género y Gobierno Corporativo. In Actas del 27 Congreso Internacional CIRIEC; Septiembre de: Sevilla, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Senent, M.J. ¿Cómo pueden aprovechar las cooperativas el talento de las mujeres? responsabilidad social empresarial e igualdad real. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2011, 105, 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Senent, M.J. Introducción a la Perspectiva de Género en la Economía Social. In Economía Social: Identidad, Desafíos y Estrategias; Fajardo, G., Senent, M.J., Eds.; CIRIEC-España: Valencia, Spain, 2014; pp. 424–440. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, I.V. Principios y valores cooperativos, igualdad de género e interés social en las cooperativas. CIRIEC Esp. Rev. Juríd. Econ. Soc. Coop. 2017, 30, 47–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, B.B. Fitting in and multi-tasking: Dutch farm women’s strategies in rural entrepreneurship. Soc. Rural 2004, 44, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, E.O.; Agbodike, F.C. Strategy for women development in Anambra state, Nigeria: Co-operative societies’ option. Rev. Public Adm. Manag. 2016, 5, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cabo, R.M.; Del Campo, J.L.; Nogués, R.G. La participación financiera y el papel de la mujer en la toma de decisiones de las sociedades cooperativas: Los consejos de administración. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2009, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P.A. Perfil de la situación de la mujer en las cooperativas de trabajo en España. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2011, 105, 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- Arcas Lario, N.; Briones Peñalver, A.J. Responsabilidad social empresarial de las organizaciones de la economía social. Valoración de la misma en las empresas de la Región de Murcia. CIRIEC Esp. Rev. Econ. Públ. Soc. Coop. 2009, 65, 134–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ribas Bonet, M.A.; Sajardo Moreno, A. La Diferente participación laboral de las mujeres entre las cooperativas y las sociedades laborales. CIRIEC Esp. Rev. Econ. Públ. Soc. Coop. 2005, 52, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez, M.E. El papel de la ACI en el progreso de la mujer en las cooperativas. Rev. Coop. Int. 1996, 1, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Borgkvist, A.; Moore, V.; Eliott, J.; Crabb, S. I might be a bit of a front runner’: An analysis of men’s uptake of flexible work arrangements and masculine identity. Gend. Work Organ. 2018, 25, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafnsdóttir, G.L.; Heijstra, T.M. Balancing work–family life in academia: The power of time. Gend. Work Organ. 2013, 20, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoletti, K.; Starr, K. Women academics and work–life balance: Gendered discourses of work and care. Gend. Work Organ. 2016, 23, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.W.; Padavic, I. Hours, scheduling and flexibility for women in the us low-wage labour force. Gend. Work Organ. 2015, 22, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, H.J. The Making of the Female Entrepreneur: A Discourse Analysis of Research Texts on Women’s Entrepreneurship; Jonkoping International Business School: Jonkoping, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, C.G.; De Bruin, A.; Welter, F. A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2009, 1, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferman, T.; Frenkel, M. The gendered state of business: Gender, enterprises and state in Israeli society. Gend. Work Organ. 2015, 22, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodeiro Pazos, D.; Calvo Babío, N.; Fernández López, S. La Gestión empresarial como factor clave de desarrollo de las spin-offs universitarias. Análisis organizativo y financier. Cuad. Gest. 2012, 12, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashi, I.; Krasniqi, B.A. Entrepreneurship and SME growth: Evidence from advanced and laggard transition economies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2011, 17, 456–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, C.; Santos, F.J.; Barroso, M.D.L.O. Cooperative essence and entrepreneurial quality: A comparative contextual analysis. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2019, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melián Navarro, A.; Campos Climent, V. Emprendedurismo y economía social como mecanismos de inserción sociolaboral en tiempos de crisis. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2010, 100, 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Foncea, M.; Marcuello, C. Spatial patterns in new firm formation: Are cooperatives different? Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 44, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Zimmer, A. The Third Sector in Spain and in Europe; Fundació General de la Unversitat València: València, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xunta de Galicia. Available online: https://www.xunta.gal/tema/c/Economia (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Cabaleiro-Casal, M.J.; Iglesias-Malvido, C.; Martinez-Fontaina, R. Co-op open membership: Economic and financial effects. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2019, 90, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; NIemand, T.; Halberstadt, J.; Shaw, E.; Syrjä, P. Social entrepreneurship orientation: Development of a measurement scale. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 977–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeta, J. Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 2006, 73, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, V.; Chaves, R. El papel de las cooperativas en la crisis agraria. Estudio empírico aplicado a la agricultura mediterránea Española. Cuadernos Desarrollo Rural 2012, 9, 175–194. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, M.; Pleite, F.M.C. El año internacional de las cooperativas. una aproximación a los desafíos del sector mediante el método Delphi. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2014, 116, 103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley-Duff, R.; Bull, M. Understanding Social Enterprise: Theory and Practice; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, L.P.; Juliá, J.F. Principios cooperativos y eficacia económica. Un análisis Delphi en el contexto normativo Español. CIRIEC Esp. Rev. Econ. Públ. Soc. Coop. 2003, 44, 231–259. [Google Scholar]

- Seguí-Mas, E.; Server Izquierdo, R.J. El capital relacional de las cooperativas de crédito en españa: Un estudio cualitativo de sus intangibles sociales mediante el análisis Delphi. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2010, 101, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Seguí-Mas, E.; Server Izquierdo, R.J. Caracterización del business capital de las cooperativas de crédito a través del análisis Delphi. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2010, 103, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Climent, V.; Apetrei, A.; Chaves-Ávila, R. Delphi method applied to horticultural cooperatives. Delphi method applied to horticultural cooperatives. MANAGE Decis. 2012, 50, 1266–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N.C.; Rourke, D.L. Experimental assessment of Delphi procedures with group value judgments. Rand Corp. Rep. Ser. 1971, 189, 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, U.; Clarke, R. Theory and applications of the Delphi technique: A bibliography (1975–1994). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1996, 53, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Wright, G. Expert Opinions in Forecasting: The Role of the Delphi Technique. In Principles of Forecasting. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science; Armstrong, J.S., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 124–144. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Mackenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J.M.; Lynch, J.G. Self-generated validity and other effects of measurement on belief, attitude, intention, and behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhoit, E.D. Opting out (without kids): Understanding non-mothers’ workplace exit in popular autobiographies. Gend. Work Organ. 2014, 21, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancheva, M.; Lynch, K.; Keating, K. Precarity, gender and care in the neoliberal academy. Gend. Work Organ. 2019, 26, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

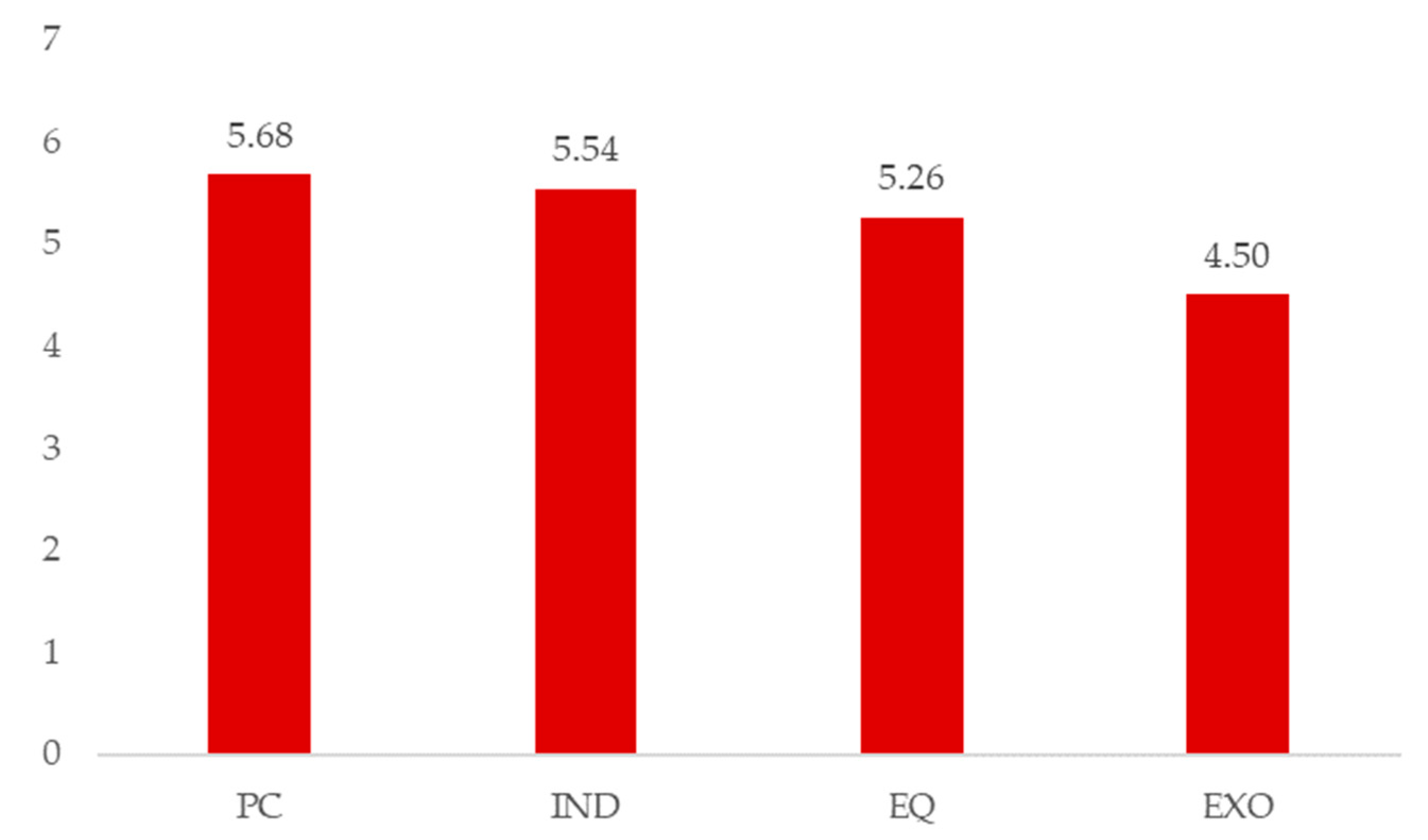

| PC Alignment to cooperative principles |

|

| IND Individual perception |

|

| EQ Equality |

|

| EXO Exogenous Factors |

|

| Type of Cooperative | Workers (Mean) | % Women |

|---|---|---|

| Agrarian | 18 | 48% |

| Consumer and users | 102 | 51% |

| Work-associated | 5 | 65% |

| Housing | 8 | 53% |

| No answer/do not know | 7 | 8% |

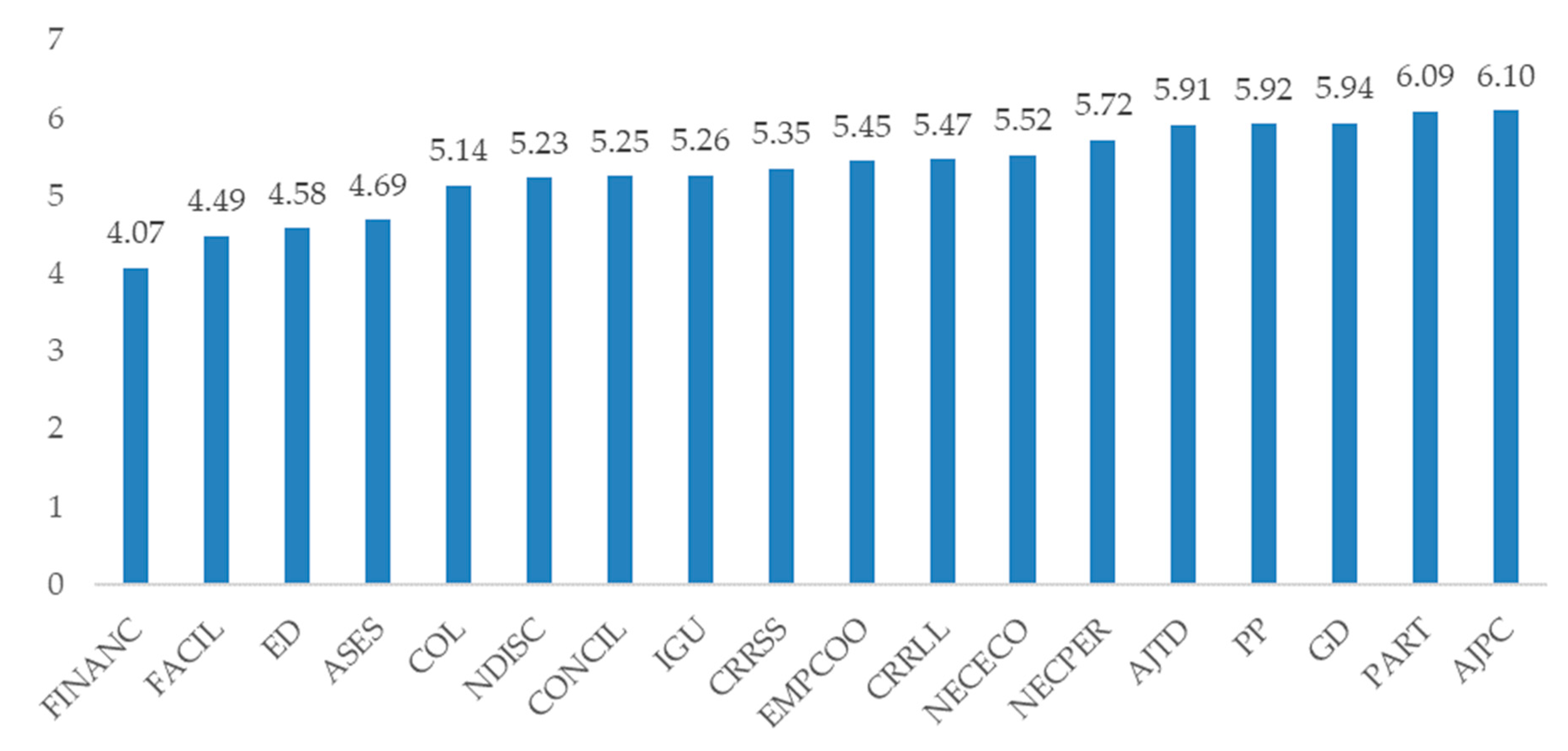

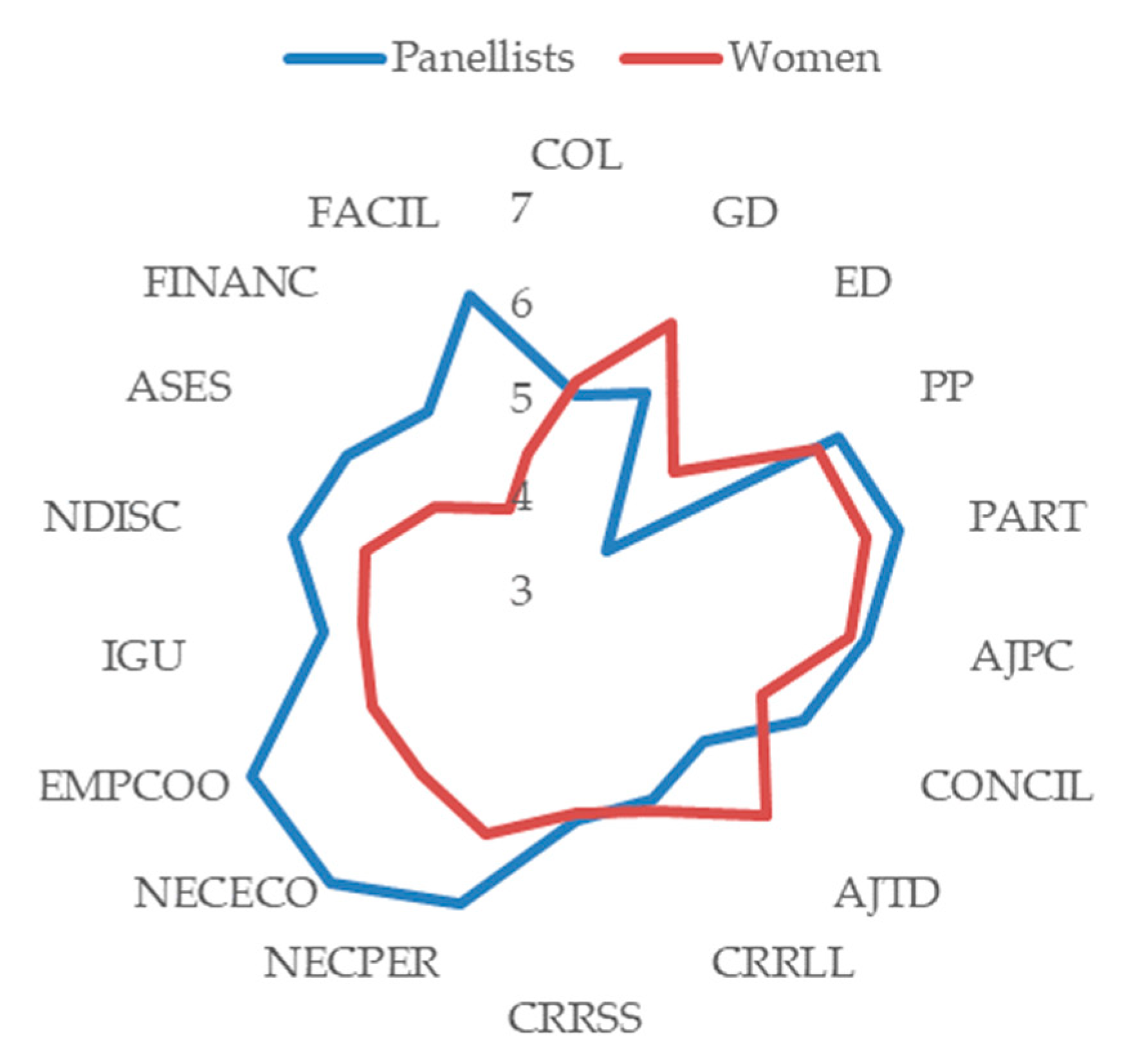

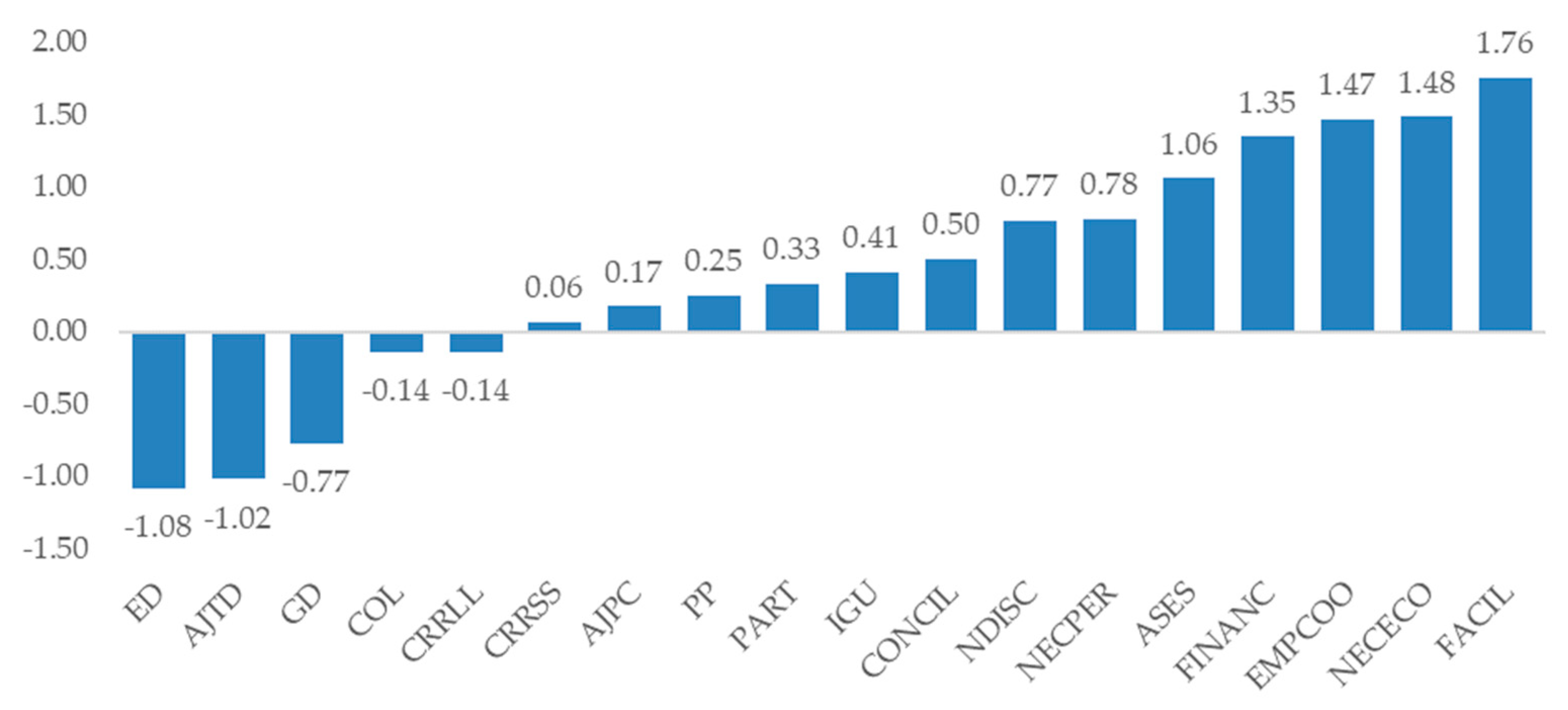

| N | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL | 99 | 5.14 | 1.76 |

| GD | 99 | 5.94 | 1.67 |

| ED | 99 | 4.58 | 1.78 |

| PP | 99 | 5.92 | 1.48 |

| PART | 99 | 6.09 | 1.35 |

| AJPC | 99 | 5.91 | 1.20 |

| CONCIL | 99 | 5.25 | 1.93 |

| AJTD | 99 | 6.10 | 1.40 |

| CRRLL | 99 | 5.47 | 1.47 |

| CRRSS | 99 | 5.35 | 1.58 |

| NECPER | 99 | 5.72 | 1.67 |

| NECECO | 99 | 5.52 | 1.55 |

| EMPCOO | 99 | 5.45 | 1.66 |

| IGU | 99 | 5.26 | 1.81 |

| NDISC | 99 | 5.23 | 1.74 |

| ASES | 99 | 4.69 | 1.85 |

| FINANC | 99 | 4.07 | 1.91 |

| FACIL | 99 | 4.49 | 1.97 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bastida, M.; Pinto, L.H.; Olveira Blanco, A.; Cancelo, M. Female Entrepreneurship: Can Cooperatives Contribute to Overcoming the Gender Gap? A Spanish First Step to Equality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062478

Bastida M, Pinto LH, Olveira Blanco A, Cancelo M. Female Entrepreneurship: Can Cooperatives Contribute to Overcoming the Gender Gap? A Spanish First Step to Equality. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062478

Chicago/Turabian StyleBastida, Maria, Luisa Helena Pinto, Ana Olveira Blanco, and Maite Cancelo. 2020. "Female Entrepreneurship: Can Cooperatives Contribute to Overcoming the Gender Gap? A Spanish First Step to Equality" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062478

APA StyleBastida, M., Pinto, L. H., Olveira Blanco, A., & Cancelo, M. (2020). Female Entrepreneurship: Can Cooperatives Contribute to Overcoming the Gender Gap? A Spanish First Step to Equality. Sustainability, 12(6), 2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062478