A Study on Bandwagon Consumption Behavior Based on Fear of Missing Out and Product Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Bandwagon Consumption Behavior

2.2. The Role of FoMO on Excessive Bandwagon Consumption Behavior

2.2.1. The FoMO Phenomenon

2.2.2. FoMO and Excessive Bandwagon Consumption Behavior

2.3. Bandwagon Consumption on FoMO Level and Product Category

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. FoMO and Bandwagon Consumption Behavior

3.2. Bandwagon Consumption Depending on FoMO Level and Product Category

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants and Procedure

4.2. Sampling

4.3. Measures

5. Findings

5.1. Sample Characteristics

5.2. Data Analysis

5.3. Empirical Results

5.4. Discussion

- ①

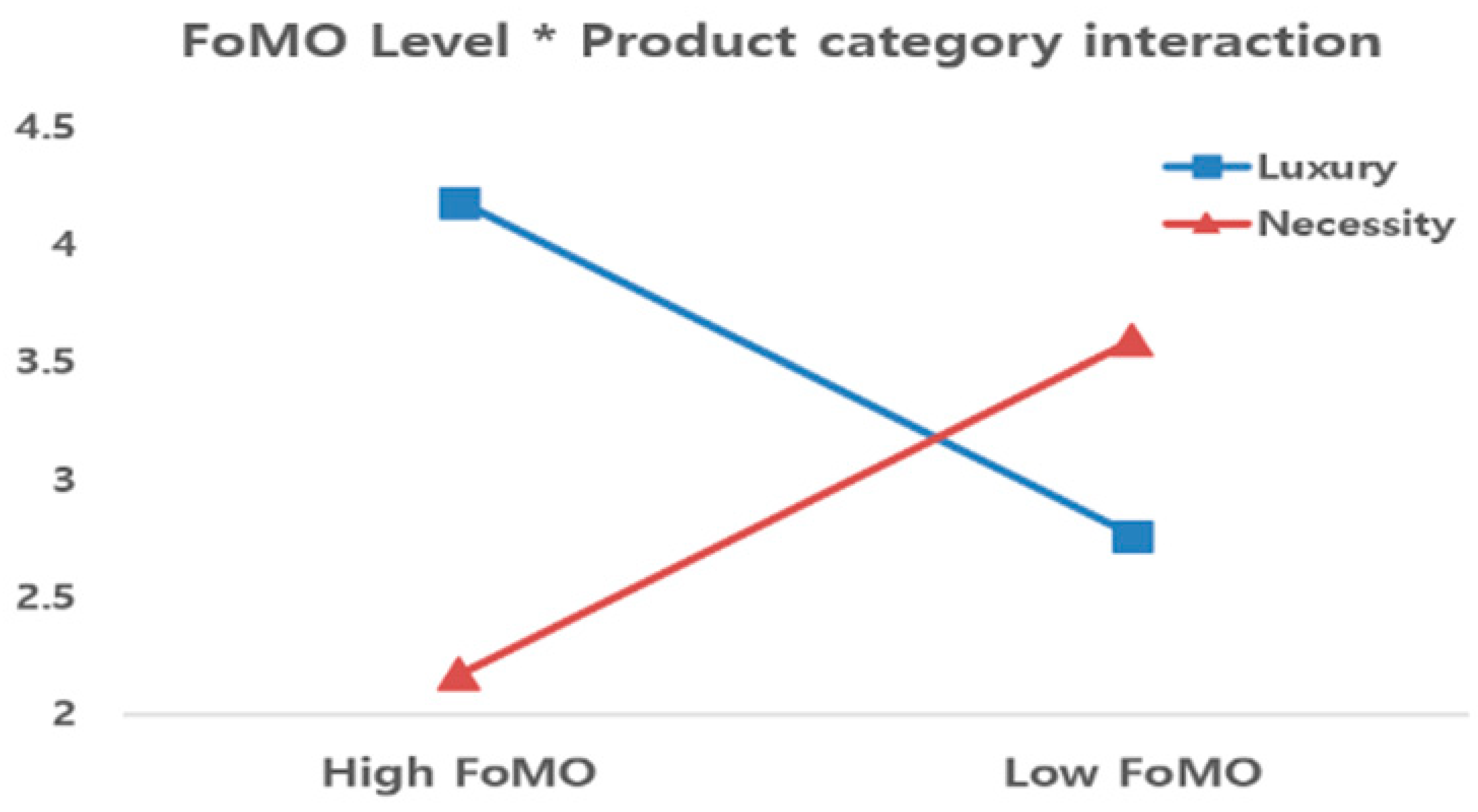

- High FoMO and Luxury: Mean and estimated marginal means for high FoMO and luxury are the highest results and indicate a significant influence on bandwagon consumption compared to other consumption behaviors. Higher levels of FoMO would stimulate bandwagon consumption through increased aspirations to join ‘the mainstream in-group’ and purchasing luxury brands representing exclusiveness and a status symbol makes it possible to feel a sense of belonging to a reference group with similar goods [19]. Also, Asian international students, especially from China and Vietnam, have mostly grown up in a relatively wealthy environment, so they have enough resources to enjoy life and purchase popular products with the financial support of their parents [19]. Based on the above consumers characteristics, Asian international students have exhibited the strongest bandwagon consumption behavior compared to other groups.

- ②

- High FoMO and Necessity: Mean and estimated marginal means for this group were the third-highest results. In spite of a higher level of FoMO, necessity brands did not show strong bandwagon consumption behavior. This means that Asian international students would not be induced to purchase necessity brands since necessity brands do not stimulate one’s psychological stability to stay connected with peers or persons of the main group they want to be associated with. Necessity brands are considered as functional, utilitarian products. In order for Asian international students with a higher level of FoMO to satisfy their needs for belonging to aspirational groups, they prove themselves by purchasing symbolic brands or exhibiting luxury brands. That is why people in this group shows weaker bandwagon consumption behavior than those who are in the group with high FoMO and luxury brands.

- ③

- Low FoMO and Luxury: The mean and estimated marginal means were the lowest for the results of this group. Those with a low FoMO are less willing to belong to a desired and aspired group. Under this psychological state, they do not need to show their status symbol, follow others blindly, or consume goods conspicuously. These people cannot stimulate luxury consumption behavior, since they need to pay more attention to the price, quality, and functional demands of products. Consumers in this group tend to show less conformity consumption behavior. Hence, the needs of purchasing luxury brands would be relatively weaker and lead to the lowest mean of bandwagon consumption behavior compared to all the other consumption behaviors examined in this research.

- ④

- Low FoMO and Necessity: The mean and estimated marginal means were the second-highest and this had a significant influence on bandwagon consumption for this group. Contrasted with the normal assumption that the tendency towards bandwagon consumption is the lowest for this group, Asian international students in this group show the second-highest bandwagon consumption behavioral trend. This indicates those who have a low FoMO are very practical, price-sensitive, and have a risk-free disposition in order to reduce failure probability [68]. Regardless of psychological traits such as belonging to a main group and anxiety of deviation, they, as foreigners and students, seek to be reasonable, risk-aversive consumers within an unfamiliar environment [55,68].

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kang, I.; Cui, H.; Son, J. Conformity Consumption Behavior and FoMO. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.E.R. The Soybean Paste Girl: The Cultural and Gender Politics of Coffee Consumption in Contemporary South Korea. J. Korean Stud. 2014, 19, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, M.Y. “It’s not just a Winter Parka”: The Meaning of Branded Outdoor Jackets among Korean Adolescents. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaikobad, N.K.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.A.; Sultana, F.; Rahman, M. Fast Fashion: Marketing, Recycling and Environmental Issues. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Invent. 2015, 4, 2319–7714. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, C.J.; Ahluwalia, R. Extending Culturally Symbolic Brands: A Blessing or a Curse? J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, C.; McKechnie, S.; Chhuon, C. Co-Creating Value for Luxury Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Malik, A.; Akram, M.S.; Chakrabarti, R. Do luxury brands successfully entice consumers? The role of bandwagon effect. Int. Mark. Rev. 2017, 34, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akturan, U.; Bozbay, Z. Attractiveness, Purchase Intention, and Willingness to Pay More for Global Brands: Evidence from Turkish Market. J. Promot. Manag. 2018, 24, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Y.; Simmons, G.; McColl, R.; Kitchen, P.J. Status and Conspicuousness–are they Related? Strategic Marketing Implications for Luxury Brands. J. Strateg. Mark. 2008, 16, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascu, D.; Zinkhan, G. Consumer Conformity: Review and Applications for Marketing Theory and Practice. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1999, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco, P.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Galinsky, A.D.; Anderson, E.T. Direct and Vicarious Conspicuous Consumption: Identification with Low-status Groups Increases the Desire for High-status Goods. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatulli, C.; Guido, G.; Nataraajan, R. Luxury Purchasing among Older Consumers: Exploring Inferences about Cognitive Age, Status, and Style Motivations. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jang, S.S. Motivational Drivers for Status Consumption: A Study of Generation Y Consumers. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 38, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Rose, R.L. Attention to Social Comparison Information: An Individual Difference Factor Affecting Consumer Conformity. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 16, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastanakis, M.N.; Balabanis, G. Between the Mass and the Class: Antecedents of the “bandwagon” Luxury Consumption Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Park, J. The Mediating Role of Consumer Conformity in E-Compulsive Buying. ACR N. Am. Adv. 2008, 35, 387–392. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Feinberg, R. E-formity: Consumer conformity behaviour in virtual communities. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2010, 4, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Cultural Technology: A Framework for Marketing Cultural Exports–analysis of Hallyu (the Korean Wave). Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.S.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y. Young Chinese Consumers’ Snob and Bandwagon Luxury Consumption Preferences. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2013, 25, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Kelly, K.M.; Cottrell, C.A.; Schreindorfer, L.S. Construct Validity of the Need to Belong Scale: Mapping the Nomological Network. J. Pers. Assess. 2013, 95, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, Emotional, and Behavioral Correlates of Fear of Missing Out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegmann, E.; Oberst, U.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M. Online-Specific Fear of Missing Out and Internet-use Expectancies Contribute to Symptoms of Internet-Communication Disorder. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2017, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. You are what they eat: The Influence of Reference Groups on Consumers’ Connections to Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Mattila, A.S. Why do we buy luxury experiences? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1848–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzgoren, E.; Guney, T. The Snop Effect in the Consumption of Luxury Goods. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. A Review and a Conceptual Framework of Prestige-Seeking Consumer Behavior. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Niesiobędzka, M. An Experimental Study of the Bandwagon Effect in Conspicuous Consumption. Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2018, 6, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastanakis, M.N.; Balabanis, G. Explaining Variation in Conspicuous Luxury Consumption: An Individual Differences’ Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2147–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.J.; Nunes, J.C.; Drèze, X. Signaling Status with Luxury Goods: The Role of Brand Prominence. J. Market. 2010, 74, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Shapiro, C. Foreign Counterfeiting of Status Goods. Q. J. Econ. 1988, 103, 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parilti, N.; Tunç, T. The Effect of Self-Esteem and Trait Anxiety on Bandwagon Luxury Consumption Behavior: Sample of a State and Private University. Abasyn Univ. J. Soc. Sci. (AJSS) 2018, 11, 254–279. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, I. Consumption as cultural interpretation: Taste, performativity, and navigating the forest of objects. In The Oxford Handbook of Cultural Sociology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, R.; Smith, P.B. Culture and Conformity: A Meta-Analysis of Studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) Line Judgment Task. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 119, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Markus, H.R. Deviance or Uniqueness, Harmony or Conformity? A Cultural Analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; He, Y. Understanding Luxury Consumption in China: Consumer Perceptions of Best-Known Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D.; Hall, B.J. Fear of Missing Out, Need for Touch, Anxiety and Depression are Related to Problematic Smartphone Use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D. College Students’ Academic Motivation, Media Engagement and Fear of Missing Out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyens, I.; Frison, E.; Eggermont, S. “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing”: Adolescents’ Fear of Missing Out and its Relationship to Adolescents’ Social Needs, Facebook use, and Facebook Related Stress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Fioravanti, G. Satisfying Needs through Social Networking Sites: A Pathway towards Problematic Internet use for Socially Anxious People? Addict. Behav. Rep. 2015, 1, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotpitayasunondh, V.; Douglas, K.M. How “phubbing” Becomes the Norm: The Antecedents and Consequences of Snubbing via Smartphone. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, B.C.; Flett, J.A.; Hunter, J.A.; Scarf, D.; Conner, T.S. Fear of Missing Out (FoMO): The Relationship between FoMO, Alcohol use, and Alcohol-Related Consequences in College Students. Ann. Neurosci. Psychol. 2015, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Nie, J.; Zeng, P.; Liu, K.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Lei, L. Envy and Problematic Smartphone use: The Mediating Role of FOMO and the Moderating Role of Student-Student Relationship. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 146, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xie, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, F.; Chu, X.; Nie, J.; Lei, L. The Need to Belong and Adolescent Authentic Self-Presentation on SNSs: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving FoMO and Perceived Social Support. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 128, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberst, U.; Wegmann, E.; Stodt, B.; Brand, M.; Chamarro, A. Negative Consequences from Heavy Social Networking in Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Fear of Missing Out. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, S.; Emirtekin, E.; Kircaburun, K.; Griffiths, M.D. Neuroticism, Trait Fear of Missing Out, and Phubbing: The Mediating Role of State Fear of Missing Out and Problematic Instagram Use. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, H.; Ozkara, B.Y. The Impact of Social Identity on Online Game Addiction: The Mediating Role of the Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) and the Moderating Role of the Need to Belong. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjarlais, M.; Willoughby, T. A Longitudinal Study of the Relation between Adolescent Boys and Girls’ Computer use with Friends and Friendship Quality: Support for the Social Compensation or the Rich-Get-Richer Hypothesis? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, B.C.; Flett, J.A.; Cody, L.M.; Conner, T.S.; Scarf, D. The Fear of Missing out (FoMO) and Event-Specific Drinking: The Relationship between FoMO and Alcohol use, Harm, and Breath Alcohol Concentration during Orientation Week. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, D.; Boniel-Nissim, M. Parent–adolescent Communication and Problematic Internet use: The Mediating Role of Fear of Missing Out (FoMO). J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 3391–3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, J.P.; Buff, C.L.; Burr, S.A. Social Media and the Fear of Missing Out: Scale Development and Assessment. J. Bus. Econ. Res. (JBER) 2016, 14, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, S.; Joseph, M. Product characteristics and Internet commerce benefit among small businesses. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2000, 9, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Purani, K. Comparing the Importance of Luxury Value Perceptions in Cross-National Contexts. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Etzel, M.J. Reference Group Influence on Product and Brand Purchase Decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Bochner, S. Culture Shock. Psychological Reactions to Unfamiliar Environments; Methuen: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Trilokekar, R.D.; Kukar, P. Disorienting Experiences during Study Abroad: Reflections of Pre-Service Teacher Candidates. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, J.; Cho, E. The young luxury consumers in China. Young- Consum. 2012, 13, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Z.G.; Krieger, H.; LeRoy, A.S. Fear of Missing Out: Relationships with Depression, Mindfulness, and Physical Symptoms. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2016, 2, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, E. Psychological Effects of Facebook Use: Links between Intensity of Facebook Use, Envy, Loneliness and FoMO; Dublin Business School: Dublin, Ireland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, V. Why do People Experience the Fear of Missing Out (FoMO)? Exposing the Link between the Self and the FoMO through Self-Construal. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2019, 50, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuksov, D.; Xie, Y. Competition in a Status Goods Market. J. Market. Res. 2012, 49, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, K.; Phan, M. Trading-Up Mass-Market Goods to Luxury Products. Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2011, 19, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maha, Z.; Oweis, S. Korea Growth Boosted by Vietnamese Boon. The Pie News, 9 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T. How Splurging Chinese Students Spell Big Bucks for Luxury Brands. Jing Daily, 27 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. Amorepacific’s Painful Dilemma. The Korea Herald, 26 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S. Sulwhasoo Takes Global Beauty Market by Storm. The Korea Times, 28 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Le, A.T.; LaCost, B.Y.; Wismer, M. International Female Graduate Students’ Experience at a Midwestern University: Sense of Belonging and Identity Development. J. Int. Stud. 2016, 6, 128–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.U.; Park, S.C. The Effects of Perceived Value, Website Trust and Hotel Trust on Online Hotel Booking Intention. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstude, K.; Mussweiler, T. What you feel is how you compare: How comparisons influence the social induction of affect. Emotion 2009, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Areas | Role of FoMO | Author(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online | SNS | Whether FoMO mediates motivation for learning and social media engagement in classes. | Alt [38] |

| How people with high FoMO act on internet platforms such as SNSs to increase their connections with other people | Wang et al. [44] | ||

| The relation between FOMO and increased stress associated with Facebook use among adolescents. | Beyens et al. [39] | ||

| The relationship between FOMO and problematic social network use. | Oberst et al. [45] | ||

| How FoMO influences individuals with a low/high level of basic need satisfaction when engaging with social media. | Casale and Fioravanti [40] | ||

| Phubbing | The relation between FoMO and phubbing during problematic Instagram use. | Balta et al. [46] | |

| smartphone addiction | The role of FoMO on smartphone addiction. | Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas [41] | |

| The research tried to reveal the role of FoMO as a mediator between envy and adolescent problematic smartphone use. | Wang et al. [43] | ||

| Game addiction | How FoMO influences the relationship between social identity and online game addiction. | Duman and Ozkara [47] | |

| Offline | Need to belong | The research looks for FoMO tendencies in adolescents with anxiety and depression. | Desjarlais and Willoughby [48] |

| Poor life satisfaction | The research examine the relationship between FoMO and low levels of life satisfaction and general moods. | Przbylski et al. [21] | |

| Negative life impact | This research tries to look for a relation between FoMO and alcohol intake along with distracted learning/driving. | Riordan et al. [42,49] | |

| Positive social bond | How to influence FoMO regarding social interaction and social approval. | Alt and Boniel-Nissim [50] | |

| Item | Characteristics | Frequency | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 106 | 48.6 |

| Female | 112 | 51.4 | |

| Total | 218 | 100.0 | |

| Nationality | China | 141 | 64.7 |

| Vietnam | 42 | 19.3 | |

| Japan | 9 | 4.1 | |

| Mongolia | 7 | 3.2 | |

| Others | 19 | 8.7 | |

| Total | 218 | 100.0 |

| Luxury | Necessity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoMO Level | Mean(SD) | Difference | t-Value | FoMO Level | Mean(SD) | Difference | t-Value |

| High (N = 118) | 4.18 (0.43) | 1.427 | 22.456 *** | High (N = 118) | 2.17 (0.38) | −1.421 | −26.586 *** |

| Low (N = 100) | 2.76 (0.51) | Low (N = 100) | 3.59 (0.41) | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Bandwagon Consumption | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoMO Level | Product Category | ||||

| Luxury | Necessity | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | Sig. | |

| High FoMO | 4.18(0.43) | 2.17(0.38) | 2.011 | 0.056 | 0.000 |

| Low FoMO | 2.76(0.51) | 3.59(0.41) | −0.837 | 0.066 | 0.000 |

| Test of Between-subject effects | Source | Type III sum of squares | Mean square | F | Sig. |

| FoMO level (A) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.943 | |

| Product category (B) | 37.342 | 37.342 | 200.111 | 0.000 | |

| A * B | 219.515 | 219.515 | 1176.347 | 0.000 | |

| Dependent Variable: Bandwagon Consumption | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoMO | Product Category |  | ||

| Luxury | Necessity | |||

| High | Mean | 4.18 | 2.17 | |

| (SD) | 0.040 | 0.040 | ||

| Low | Mean | 2.76 | 3.59 | |

| (SD) | 0.043 | 0.043 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, I.; Ma, I. A Study on Bandwagon Consumption Behavior Based on Fear of Missing Out and Product Characteristics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062441

Kang I, Ma I. A Study on Bandwagon Consumption Behavior Based on Fear of Missing Out and Product Characteristics. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062441

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Inwon, and Ilhwan Ma. 2020. "A Study on Bandwagon Consumption Behavior Based on Fear of Missing Out and Product Characteristics" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062441

APA StyleKang, I., & Ma, I. (2020). A Study on Bandwagon Consumption Behavior Based on Fear of Missing Out and Product Characteristics. Sustainability, 12(6), 2441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062441