The Post-Anthropocene Diet: Navigating Future Diets for Sustainable Food Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Pre-Anthropocene Diet: Indigenous Ontologies

2.1. What Is Pre-Anthropocene?

2.2. What Are Pre-Anthropocene Ontologies?

2.3. How Do Pre-Anthropocene Ontologies Consider Temporality?

2.4. What Are Examples of Pre-Anthropocene Diets?

3. The Anthropocene Diet: Anthropocentric Ontologies

3.1. What Is the Anthropocene?

3.2. What Are Anthropocene Ontologies?

3.3. How Do Anthropocene Ontologies Consider Temporality?

3.4. What Are Examples of Anthropocene Diets?

4. The Post-Anthropocene Diet: Ecosophical Ontologies

4.1. What Post-Anthropocene Is Possible?

4.2. What Are Possible Post-Anthropocene Ontologies?

4.3. How Would Post-Anthropocene Ontologies Consider Temporality?

4.4. What Would Be Examples of Post-Anthropocene Diets?

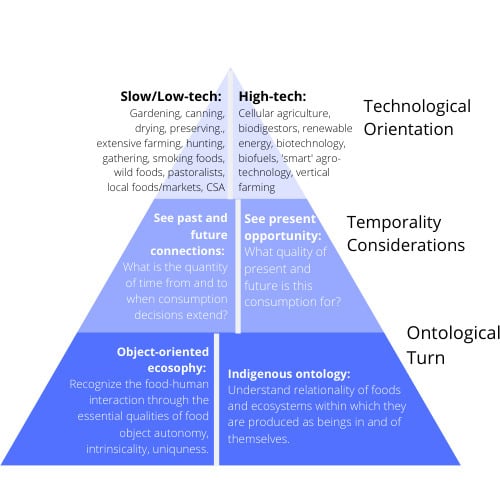

5. Ontologically-Based Dietary Guidelines

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.M.; Beare, D.J.; Bennett, E.M.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Ingram, J.S.; Jaramillo, F.; Ortiz, R.; Ramankutty, N.; Sayer, J.A.; Shindell, D. Agriculture production as a major driver of the earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN FAO. FAOSTAT Land Use; UN FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UN FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture; UN FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M.; Williams, D.R.; Kimmel, K.; Polasky, S.; Packer, C. Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention. Nature 2017, 546, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, R.J.; Rosenberg, R. Spreading dead zones and consequences for marine ecosystems. Science 2008, 321, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molden, D. Water for Food Water for Life: A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tubiello, F.N.; Salvatore, M.; Cóndor Golec, R.D.; Ferrara, A.; Rossi, S.; Biancalani, R.; Federici, S.; Jacobs, H.; Flammini, A. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land use Emissions by Sources and Removals by Sinks; Statistics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S. Climate change and food systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, L.; Hawkes, C.; Waage, J.; Webb, P.; Godfray, C.; Toulmin, C. Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition: Food Systems and Diets: Facing the Challenges of the 21st Century; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nyström, M.; Jouffray, J.; Norström, A.V.; Crona, B.; Jørgensen, P.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Bodin, Ö.; Galaz, V.; Folke, C. Anatomy and resilience of the global production ecosystem. Nature 2019, 575, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Nisbett, N.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Toulmin, C.; Whiteley, R. The future of the global food system. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2769–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.J. Geology of mankind. In A Pioneer on Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Change in the Anthropocene; Crutzen, P.J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J. The “anthropocene”. In Earth System Science in the Anthropocene; Crutzen, P.J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.; Zalasiewicz, J.; Waters, C. The Anthropocene: A geological perspective. In Sustainability and Peaceful Coexistence for the Anthropocene; Heikkurinen, P., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A. Food in the anthropocene: The EAT–lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Williams, M.; Smith, A.; Barry, T.L.; Coe, A.L.; Bown, P.R.; Brenchley, P.; Cantrill, D.; Gale, A.; Gibbard, P. Are we now living in the anthropocene? Gsa Today 2008, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.L.; Maslin, M.A. Defining the anthropocene. Nature 2015, 519, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P.; Ruuska, T.; Wilén, K.; Ulvila, M. The anthropocene exit: Reconciling discursive tensions on the new geological epoch. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 164, 106369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P.; Rinkinen, J.; Järvensivu, T.; Wilén, K.; Ruuska, T. Organising in the anthropocene: An ontological outline for ecocentric theorising. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4146–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummu, M.; Fader, M.; Gerten, D.; Guillaume, J.H.; Jalava, M.; Jägermeyr, J.; Pfister, S.; Porkka, M.; Siebert, S.; Varis, O. Bringing it all together: Linking measures to secure nations’ food supply. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 29, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, D.R.; Bartolini, F.; Kugelberg, S.; Leip, A.; Oenema, O.; Uwizeye, A. Nitrogen pollution policy beyond the farm. Nat. Food 2019, 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnlein, H.; Eme, P.; de Larrinoa, Y.F. 7 indigenous food systems: Contributions to sustainable food systems and sustainable diets. In Sustainable Diets: Linking Nutrition and Food Systems; CAB International: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 64. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, A.E. Eating for the post-Anthropocene: Alternative proteins and the biopolitics of edibility. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2018, 43, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B. Gendered biopolitics of public health: Regulation and discipline in seafood consumption advisories. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2012, 30, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, L.; Green, R.; Joy, E.J.; Smith, P.; Haines, A. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans; Dietary Guidelines: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- UN FAO. International Scientific Symposium: Biodiversity and Sustainable Diets United Against Hunger: 3–5 November; UN FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eker, S.; Reese, G.; Obersteiner, M. Modelling the drivers of a widespread shift to sustainable diets. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T. Food control or food democracy? Re-engaging nutrition with society and the environment. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, S. Ontologies of indigeneity: The politics of embodying a concept. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 21, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Wolf, C.; Newsome, T.M.; Barnard, P.; Moomaw, W.R. World scientists’ warning of a climate emergency. Bioscience 2019, 70, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, K. Our Ancestors’ Dystopia Now: Indigenous Conservation and the Anthropocene. In The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities; Heise, U., Christensen, J., Niemann, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, G. Prince of Networks: Bruno Latour and Metaphysics; re. Press: Prahran, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, G. Tool-Being: Heidegger and the Metaphysics of Objects; Open Court: Peru, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ulvila, M.; Wilén, K. Engaging with Plutocene: Moving Towards Degrowth and Post-Capitalistic Futures. In Sustainability and Peaceful Coexistence for the Anthropocene; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkurinen, P. On the emergence of peaceful coexistence. In Sustainability and Peaceful Coexistence for the Anthropocene; Heikkurinen, P., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- NATIFS. The Souix Chef. Foundations of an Indigenous Food Systems Model. Available online: https://www.natifs.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Hunter, D.; Özkan, I.; Moura de Oliveira Beltrame, D.; Samarasinghe, W.L.G.; Wasike, V.W.; Charrondière, U.R.; Borelli, T.; Sokolow, J. Enabled or disabled: Is the environment right for using biodiversity to improve nutrition? Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnlein, H.V.; Receveur, O. Dietary change and traditional food systems of indigenous peoples. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1996, 16, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Future of Food and Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2017.

- McGregor, D. Honouring our Relations: An Anishnaabe Perspective. Speak. Environ. Justice Can. 2009, 27, 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, N. Indigenous Poetics in Canada; Wilfrid Laurier University Press: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson, L.; Morrissette, V.; Régallet, G. Our Responsibility to the Seventh Generation: Indigenous Peoples and Sustainable Development; International Institute for Sustainable Development Winnipeg: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, T.D. Chronos and Kairos: Multiple futures and damaged consumption meaning. Consum. Cult. Theory 2015, 17, 129–154. [Google Scholar]

- NASA/GISS (National Aeronautics and Space Administration/Goddard Institute for Space Studies). Climate Data; NASA/GISS: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Barnosky, A.D.; Hadly, E.A.; Bascompte, J.; Berlow, E.L.; Brown, J.H.; Fortelius, M.; Getz, W.M.; Harte, J.; Hastings, A.; Marquet, P.A. Approaching a state shift in Earth’s Biosphere. Nature 2012, 486, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purser, R.E.; Montuori, A. Ecocentrism is in the eye of the beholder. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 611–613. [Google Scholar]

- Purser, R.E.; Park, C.; Montuori, A. Limits to anthropocentrism: Toward an ecocentric organization paradigm? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 1053–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, B.; Mellor, M.; O’Brien, G. Sustainable development: Mapping different approaches. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M. Global nutrition dynamics: The world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L.; Benton, T.; Herrero, M.; Krishnapillai, M.; Liwenga, E.; Pradhan, P.; Rivera-Ferre, M.; Sapkota, T.; et al. Food Security. In Climate Change and Land; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomisto, H.L. The complexity of sustainable diets. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 720–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi, A.; Leip, A.; De Boer, I.; Slegers, P.M.; Ziegler, F.; Temme, E.H.; Herrero, M.; Tuomisto, H.; Valin, H.; Van Middelaar, C.E. The potential of future foods for sustainable and healthy diets. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J. A food systems approach to researching food security and its interactions with global environmental change. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J.; Tubiello, F.N. Global food security under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19703–19708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A summary. Inquiry 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, A. Ecology, Community and Lifestyle: Outline of an Ecosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T.; Palsson, G. Biosocial Becomings: Integrating Social and Biological Anthropology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomisto, H.L.; Teixeira de Mattos, M.J. Environmental impacts of cultured meat production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6117–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattick, C.S.; Landis, A.E.; Allenby, B.R.; Genovese, N.J. Anticipatory life cycle analysis of in vitro biomass cultivation for cultured meat production in the united states. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11941–11949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusk, J.L.; McCluskey, J. Understanding the impacts of food consumer choice and food policy outcomes. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Epoch | Pre-Anthropocene | Anthropocene | Post-Anthropocene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ontologies/Worldviews | Indigenous wisdom (histories, stories, languages, artistry, spirituality), relational, connected to the land and all beings, all beings have rights in and of themselves, humans should not interfere with the duties of other beings to each other, protecting natural resources | Human-centered, perpetuated human-nature dualism, agential anthropocentrism, neoliberal, colonial, productivist, efficiency | Object-oriented ecosophy, systemic, complex and adaptive, all objects have intrinsicality, autonomy, and uniqueness, equitable ecocentrism, de-/post-colonial, sufficiency |

| Consideration of Temporality | Connected to ancestors and to progenitors, decisions are made for the seventh generation | Shallow, immediate gratification, efficient, future generations supplanted for present consumption | Present consumption regards the needs of/possible impacts on the future, is cognizant of historical context |

| Examples of Diets in practice | Wild food, hunting, gathering, food preservation (drying, salting, smoking, etc.), pastoralists, nomadic, identification, soil maintenance, ancestral seeds, medicinals, cultural cooking techniques | Highly processed, energy-dense, nutrient-deplete, sugar-sweetened, globalized, heavy carbonization, contributing to/leading the environmental crisis, cheap, fast foods, convenience, high food wastage | Local, seasonal, foraging, reduce food waste, ‘sustainable’, plant-based, within planetary boundaries, growing own food/permaculture, slow food, return to traditional/culturally appropriate, affordable, soil regenerative, technologically-produced ecological diets |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazac, R.; Tuomisto, H.L. The Post-Anthropocene Diet: Navigating Future Diets for Sustainable Food Systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062355

Mazac R, Tuomisto HL. The Post-Anthropocene Diet: Navigating Future Diets for Sustainable Food Systems. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062355

Chicago/Turabian StyleMazac, Rachel, and Hanna L. Tuomisto. 2020. "The Post-Anthropocene Diet: Navigating Future Diets for Sustainable Food Systems" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062355

APA StyleMazac, R., & Tuomisto, H. L. (2020). The Post-Anthropocene Diet: Navigating Future Diets for Sustainable Food Systems. Sustainability, 12(6), 2355. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062355