Is Human Capital Ready for Change? A Strategic Approach Adapting Porter’s Five Forces to Human Resources

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

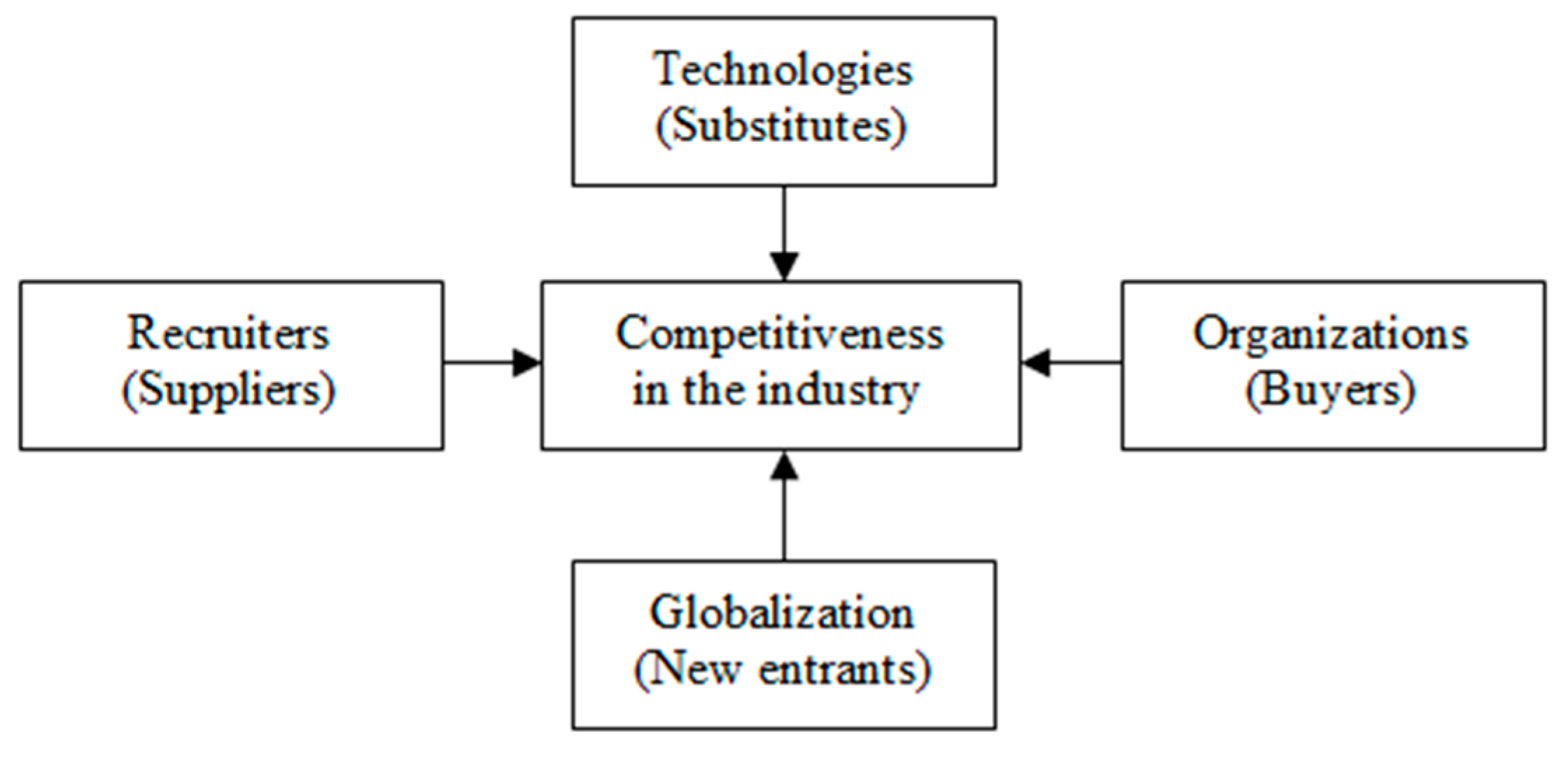

3. Porter’s Five Forces Model adapted to Human Capital

- The rivalry between competitors: The attractiveness of an industry depends on the level of competitors’ rivalry. The competitiveness in the area is high if: There are many companies with similar size and profits; the barriers to exit the business are high, because of the degree of specialization or the emotional involvement of the management; the sector is moving slowly and the customers are not aware of the advantages of the products/services delivered. Usually, the competitors use price wars as methods to win the market, but this is just a short-term strategy. Eliminating the competitors is a weak tactic, because in a globalized competitive environment, new entrants may arise from all over the world.

- The buyers’ power of negotiation: The clients’ influence may be strong if their number is low in the industry and they buy a large volume, so they can bargain on the price of the products/services. They may represent a threat if they can easily switch to another supplier or may decide to manufacture the suppliers’ products. The same analysis may be developed for intermediate customers.

- The suppliers’ power of negotiation: A small number of suppliers may generate monopoly or oligopoly, which can give them uncontrolled power. The same situation may occur if the clients’ costs for switching to other suppliers are high, or if their incomes come from more industries (diversification).

- The threat of new entrants: New entrants can be obstructed by economies of scale, or other methods to reduce the costs. If the barriers for new entrants are high, their presence in new markets is difficult. However, when the strategy of strong companies is differentiation, they may plan initial losses, until their position in the market becomes consolidated.

- According to Porter, the entry barriers may be: Economies of scale (existing companies may use economies of scale, because they can control costs along the value chain: Manufacture, research, or marketing for many units), network effects (branded companies may give discounts or other advantages for loyal clients, which act like barriers to new entrants), clients switching costs (clients find it hard to switch to other suppliers because they depend on the products, e.g. software for PC, mobile data), or supremacy of incumbents (intellectual property, discounts from suppliers, geographic advantage, or other things).

- The threat of substitutes: The substitutes may be a threat to the products in a specific market if their prices are competitive, or if they incorporate modern materials or technologies. The barriers that can block the substitutes may be the differentiation of products or the decrease of costs.

3.1. Competitiveness in the Economic Sector

- Age and gender:There are some biases coming from individuals’ stereotypes that may obstruct a person in their decision to find a better job. The regulations all over the world try to protect the workforce against discrimination, like age, gender, disabilities, religion, or others [46,47].The researchers in the field argue that the employers prefer men in leadership positions because of their native features: Power, agressiveness, competitive spirit, or resistance to stress [48,49]. Even if women have the same level of education and experience as men, and they represent 45% of the total human capital in Europe, only 35% of them have managerial roles in organizations [50]. However, the number of manager women is increasing [51].Statistics show that women are paid lower salaries than men [52]. Moreover, there is an increase of single parent families headed by women, so their expectations are related to flexible jobs, childcare, or working from home. According to the US Census Bureau 2017, around 12 million American families are single parenting, and 84% are headed by single moms. In terms of incomes, the annual average is 35,400 USD, compared to the income of a married couple (85,300 USD).Age is another bias in switching jobs. Studies show that, beginning with job advertisements and continuing with the methods of recruitment, older persons are affected by age discrimination [53,54].The number of employees aged 65+ is expected to grow from 19% in 2018 to 29% by 2060, which will represent a major problem in finding talents [55].Even if regulations forbid, the employers try to find ways to restrict the hiring of older people [56,57] because of their difficulties in adapting to new organizational culture, the decrease in productivity, and the level of compensations they require. However, these stereotypes are false, because this category of employees have skills developed in time, are devoted to the organization, and are exposed to less accidents in work [58].

- Psychological barriers:Most of these are subjective and are closely related to the personality and employment background of the individual. The person may think that he/she is too old to find a better job, based on what happened on the previous job search.Another problem might be the lack of self-confidence in the actual skills, compared to other employees in similar positions, so the individuals do not act because of a fear of failing [59].A major problem in the age of modern technologies represents the disappearance of some specializations. People find it hard to develop new competencies and to start an unpredictable journey, especially when they have an age handicap [60].

- Lack of updated skills:The last years brought an odd situation: There are a lot of vacant jobs in each country, but people are still unemployed and looking for jobs. Statistics show that in 2018, 43% of people in USA were hired for non-tech jobs, and 57% for tech-jobs [26].Today, most of the specialized jobs require a graduation diploma. However, the real skills are not there, even if graduating is equal to career success. Considering that the tuitions represent a big effort for the students (9000–30,000 USD per year in USA, 4000 USD yearly in Canada), the decision in choosing vocational or university studies is an important one, because statistics show that two thirds of the students graduate with an average of 29,000 USD debt [61].The number of graduates reached 70% of the active population, in contrast with the number of white-collar jobs, which is around 25%. According to their level of education, the companies will hire them for specific jobs. According to a study developed by International Policy Digest in 2019, the jobs suffered some important changes in time: management jobs represented 31% in 1990 compared to 40% in 2018; sales office jobs were 28% in 1990 and 22% in 2018; blue collar jobs decreased from 26% in 1990 to 21% in 2018; low payed services jobs increased from 15% in 1990 to 17% in 2018.Because blue-collar jobs are considered dirty jobs (they require manual competencies), the younger generation goes for white-collar jobs, which are more creative, elegant, and better paid. However, the evolution presented above shows that the number of blue-collar jobs is decreasing, maybe because they are replaced with robots.Another important fact is the training for jobs. The managers expect the employees to be trained when they hire them, so few of them want to pay for developing skills.

3.2. The Power of Recruiters

- The companies specialized in recruiting workforce:In a competitive business environment, a qualified workforce is difficult to find. Companies may use precious time to recruit persons to fit a job. Therefore, they often hire them via recruiting agencies, which have many candidates, some of them already tested and selected.In fact, recruiters play a double role: Experts for companies that seek suitable candidates for vacant jobs, and facilitators for people who are in the process of finding jobs or changing existing ones.

- The universities and vocational schools:Schools should represent the nursery for future best employees or business owners. Information flows freely, so the younger generation have the opportunity to check the statistics concerning the employability index, which is one of the reasons for choosing a certain high-school or university. Therefore, the educational institutions should update their curricula in order to be in trend with the skills required by the organizations [64].The Top 10 Graduate Employability universities are: Five from the USA (MIT, Stanford, UCLA, Harvard, UCB), two from Australia (University of Sydney and University of Melbourne), two from the UK (Cambridge and Oxford), and one from China (Tsinghua University) [65].

- Headhunters hired by companies to attract talent from the competition:There is a huge difference between headhunters and recruiters: While the recruiting companies select candidates from a list of existing persons who fit the requirements, the headhunters represent the company willing to hire and act like advocates for attracting talent.

- Personal development:Organizations are constantly targeting the performance of their employees, so in order to improve it they provide training for updating the skills needed for their jobs. However, some of the employees feel that they are able to develop more skills that may be useful in time, especially when competition is harsh. They will take e-courses or pay for extra training.

- Internships:Internships are methods to acquire or improve people’s knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs). No matter if they are paid or for free, after working hours or on holidays, the purpose is a practical one, and it strengthen the employee’s position in the organization, because he/she is supposed to perform better.

- Volunteering:Volunteering provides both knowledge and experience. It may be performed inside or outside the organization. These actions will allow the individuals to learn new things and practice them, without leaving a safe job. It adds value to existing skills, or may be the start of a new journey. After volunteering, employees may find they are comfortable in jobs related to marketing, sales, human resources, or others.

3.3. The Power of Organizations

- In a niche industrial sector;

- When the organization has devoted clients and long-term contracts;

- If the company is a brand and has a good image, so the jobs are stable;

- The jobs are not threatened by substitutes.

- Costs for firing and hiring the workforce:These are an organization’s direct costs that may affect the profit, so this is a tough decision.According to the Society of Human Resource Management and the American National Standards Institute, the cost for hiring (CPH) is calculated with the formula:CPH =Based on Porter’s theory, if the labor market in a specific specialization is crowded, the companies find it easy to replace the workers because there is a large pool of people. On the other hand, if the required skills are hard to find, the management is forced to keep the employees, even if they are not performant.Surveys done by some researchers [69] show that almost half of the employers have difficulties in finding talented employees.

- Industry dynamics:The organizations perform in a constantly changing environment and they have to adapt to market demands. The barriers to change will help companies in predicting the number of jobs and specializations that will have a crescent trend or a downsizing one [70].There is also a change in the age of the world workforce population. Some segmentation may be identified and evaluated: Veterans (born 1939–1947), baby boomers (born 1948–1963), Generation X (born 1964–1978), Generation Y (born 1980–1990), and Millennial (born 1990–2000) [71].The skilled employees may have the power to persuade the company’s management to keep them: A creative and innovative person is a valuable asset.

- Scarcity of talents:The organizations face some real problems: The presence of unemployment in the labor market and the lack of updated skills. Baby Boomers have retired, Generation X is rather mature, and the next generations are determined to make fast and easy money. Therefore, a strong specialized company is forced to keep actual employees and train them for updating their skills.

- Emotional barriers:Emotion is manifested when the organization is loyal to its employees and has assumed responsibilities that are not stipulated in the employment contract, and some affective connections have been established between managers and subordinates. Especially in small companies, a workforce is like a family; they know everybody’s personal problems, and these aspects influence, most of the time in a negative manner, the decisions concerning firing employees with bad performances.However, this approach has effects on costs, quality, and delivery of the products or services. In the long run, the image of the company is in danger.

- Legislation:The labor legislation is specific for each country, and it aims to protect employees against the organizations’ abuses regarding firing: Discrimination of any type, like disabilities, pregnancy, age, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or other civil rights.

3.4. The Threat of Globalization

- Diversification: Both for individuals and teams, acquired through lifelong learning, for new skills related or not to the existing ones, or for any competencies that are hard to replicate. Multi-task teams benefit from synergy, so they will be difficult to replace with individuals who cannot compete as separate entities;

- Product differentiation: In niche sectors, loyal costumers may force the negotiation for manufacturing of specific products by some employees who proved their skills and behavior in previous projects;

- Experience as teams: The existing organizations in the market have employees with theoretical and practical backgrounds, experience in teamwork, and organizational behavior, which may represent a solid advantage, because new entrants will need time to reach the same level of competencies and adaptability.

3.5. The Threat of Modern Technologies

- They are suitable for the organization’s goals;

- They do not generate excessive expenses for the company;

- They follow aggressive politics.

4. Discussions

- People and products may travel freely in countries all over the world, which may affect competitiveness in a good way;

- Communication allows the exchange of information, but it is an advantage only if the users (consumers, suppliers, or workforce) are able to filter and rank it;

- The cultural bias is diluted, because individuals (or groups) may adopt organizational behavior from others, if they are comfortable with them, and learn to be more tolerant;

- People coming from crowded societies (such as China or India) to developed countries may be a threat to locals because they accept low wages for skilled jobs, which can generate unemployment for native employees;

- Multi-national companies may expand their businesses (especially manufacturing) in poor countries, so they may generate incomes, and in the long term, the increase of GDP for the whole society;

- The relocation of business in poor countries may be seen as a source of threat for the environment, as well as for workers (low wages, poor working conditions, lack of health and security care, and other things).

- Competitiveness in the industry: If the competitivity is harsh, the employees should update their skills to continue their activity in the present workplace and/or acquire transferable skills which will allow them to switch between employers. Recent studies show that the industrial sectors where people have the most transferable skills are: Construction and engineering (80%), energy and environment (70%), technology (60%), automotive and healthcare (50%), retail, business and finance (30%), and transportation and storage (20%) [87]. In the case of graduates, they should apply for jobs that allow them to express their adaptability, creativity, or teamwork.

- The power of recruiters: Both internal or external, recruiters choose the right candidates for the available jobs. The applicants should highlight their skills because, especially for obsolete jobs, only the experience is not relevant. So, in order to succeed, the candidates have to find those soft skills that may make the difference. They can also go for temporary jobs, in order to increase their incomes, while learning new things. Universities and high schools may be seen as recruiters, because they prepare the graduates for the workforce market. These educational institutions will be chosen by candidates only if they deliver updated information, connected to practice in the field.

- The power of organizations: The employees’ skills are performance drivers for organizations. Therefore, the companies will hire only talents for key jobs in order to gain competitive advantage. Another important aspect is the flexibility and adaptability of the workforce in the business environment. These requests should be acknowledged by actual and future employees as well because, by being prepared, they may face the challenges. Even changing career or choosing a first entry job are decisions that depend on market demands.

- The threat of globalization: The exodus of human capital migrating from less developed to highly developed countries is a phenomenon which can no longer be ignored. The main challenge for the locals is to keep their actual jobs based on competitive skills. Globalization is an opportunity for companies to attract talent and replace the employees who do not possess enough competencies. When a person is in the process of switching job, or wants to prepare for a new one, the threat of new entrants has to be considered and evaluated in a specific industrial sector.

- The threat of modern technologies: Automation and artificial intelligence are affecting the number and structure of jobs. Due to robots and software, a lot of specializations will disappear, both for operational and managerial jobs. These aspects should be analyzed when a person is in the process of planning their career. In the case of pilots, for example, by 2030 the number per flight will be cut from three to two because of AI. On the other hand, a study developed by Dell shows that 85% of the jobs in 2030 have not been created yet.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Armstrong, M.; Taylor, S. Armstrong’s Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, 14th ed.; Kogan Page: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J. Strategy and Human Resource Management, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, G.; Smith, P.E. Strategic Human Resources Management: An International Perspective, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 80–101. [Google Scholar]

- HR Daily Advisor. The Future of Workforce Planning. Available online: https://hrdailyadvisor.blr.com/2017/01/17/future-workforce-planning/ (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Bayraktar, O.; Sencan, H. Employees’ Approaches to Human Resources from the Asset-Resource Concepts Perspectives. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 116–127. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, P.J.; Simpson, E. Resource-Based Theory, Competition and Staff Differentiation in Africa: Leveraging Employees as a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage. Am. J. Manag. 2017, 17, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bostjancic, E.; Slana, Z. The Role of Talent Management Comparing Medium-Sized and Large Companies—Major Challenges in Attracting and Retaining Talented Employees. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, L.S.; Faley, R.H.; Faley, S.G. Human Resource Management: Managerial Tool for Competitive Advantage, 6th ed.; Kendall Hunt: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2012; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- PwC Annual Report 2017–2018. Available online: https://www.pwc.nl/nl/assets/documents/pwc-annual-report-2017–2018.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Kenny, V.S. Employee Productivity and Organizational Performance: A Theoretical Perspective. MPRA 2019. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/93294/ (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Verburg, R.M.; Nienaber, A.; Searle, R.H.; Weibel, A.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Rupp, D.E. The Role of Organizational Control Systems in Employees’ Organizational Trust and Performance Outcomes. SAGE J. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitao, J.; Pereira, D.; Goncalves, A. Quality of Work Life and Organizational Performance: Workers’ Feelings of Contributing, or Not, to the Organization Productivity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motyka, B. Employee Engagement and Performance: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Manag. Econ. 2018, 54, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabieh, L.E. Processes and Mechanisms of Creating and Maintaining Sustainable Competitive Advantage. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2014, 21, 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Al Adresi, A.; Darun, M.R. Determining Relationship between Strategic Human Resource Management Practices and Organizational Commitment. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, J. The Practice of Human Resource Management. Inst. Public Adm. 2017. Available online: https://www.ipa.ie/_fileUpload/Documents/THE_PRACTICE_OF_HRM.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2019).

- Hamadamin, H.H.; Atan, T. The Impact of Strategic Human Resource Management Practices on Competitive Advantage Sustainability: The Mediation of Human Capital Development and Employee Commitment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totterdill, P.; Exton, T.; Exton, R.; Gold, M. High-performance Work Practices in Europe: Challenges of Diffusion. Eur. J. Workplace Innov. 2016, 2, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy. Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, 1st ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik, P. Shortage of Talents—A Challenge for Modern Organizations. Int. J. Synerg. Res. 2017, 6, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends. Rewriting the Rules for the Digital Age. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/HumanCapital/hc-2017-global-human-capital-trends-gx.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Noor, U.H.; Shahjehan, A. Role of Employer Branding Dimensions on Employee Retention: Evidence from Education Sector. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goessling, M. Attraction and Retention of Generations X, Y and Z in the Workplace. Integr. Stud. 2017. Available online: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/bis437/66 (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- CPWR. The Center for Construction Research and Training. Development of a Workforce Sustainability Model for Constructions. Available online: https://bit.ly/2WrRKet (accessed on 12 December 2018).

- Hill, C.W.L.; Jones, G.R.; Schilling, M.A. Strategic Management Theory, 11th ed.; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2015; pp. 82–108. [Google Scholar]

- Glassdoor Research Report. Job Market Trends: Five Hiring Disruptions to Watch in 2019. Available online: https://www.glassdoor.com/research/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/12/FINALGlassdoor2019JobTrends.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.; Pfeffer, J. Hidden Value: How Great Companies Achieve Extraordinary Results with Ordinary People; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rennie, W.H. The Role of Human Resource Management and the Human Resource Professional in the New Economy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Khandekar, A.; Sharma, A. Organizational Learning in Indian Organizations: A Strategic HRM Perspective. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2005, 12, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K.; Whittington, R. Exploring Corporate Strategy, 8th ed.; Prentice Hall, Financial Times: Essex, UK, 2008; pp. 473–515. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, P.M.; Snell, S.A.; Jacobsen, H.H. Current Approaches to HR Strategies: Inside-Out versus Outside-In. Hum. Resour. Plan. 2004, 27, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable Human Resource Management: A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Physica: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Available online: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783790821871 (accessed on 7 December 2019).

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A. The Central Role of Human Resource Management in the Search for Sustainable Organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 2133–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Dunford, B.B.; Snell, S.A. Human Resources and the Resource Based View of the Firm. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, J.W.; Hilton, M.L. Education for Life and Work. Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, R.; Turner, R. Leadership Competency Profiles of Successful Project Managers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, D. Assessment in Organizations. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2004, 53, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, K.; Rahim, E. Application of Multi Criteria Decision Approaches for Personnel Selection Problem: A Survey. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2015, 5, 14–29. [Google Scholar]

- Onalenna, S.; Robin, G.; Philip, C.H.; Pauline, B. Understanding Human Resource Management Practices in Botswana’s Public Health Sector. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1284–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Laprade, N. The Competitive Edge: Creating a Human Capital Advantage for Kentucky. Foresight 2006, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Analoui, F.; Cusworth, J. Strategic Human Resource Management and Resource-Based Approach: The Evidence from the British Manufacturing Industry. Manag. Res. News 2004, 27, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucke, M. Is Competition Always Good? J. Antitrust Enforc. 2013, 1, 162–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Switching Costs and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invent. 2013, 2, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R. The Globotics Upheaval: Globalization, Robotics, and the Future of Work, 1st ed.; Weidenfeld & Nicolson: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 185–210. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Occupational Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap: A Job Half Done. Available online: https://iwpr.org/publications/occupational-segregation-and-the-gender-wage-gap-a-job-half-done/ (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- Davis, P.J.; Frolova, Y.; Callahan, W. Workplace Diversity Management in Australia: What Do Managers Think and What are Organizations Doing? Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2016, 35, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crites, S.N.; Dickson, K.E.; Lorenz, A. Nurturing Gender Stereotypes in the Face of Experience: A Study of Leader Gender, Leadership Style, and Satisfaction. J. Organ. Cult. Commun. Confl. 2015, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff, N.J.; Vescio, T.K.; Dahl, J.L. (Still) Waiting in the Wings: Group based Biases in Leaders’ Decisions About to Whom Power is Relinquished. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 57, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. Only 1 Manager Out of 3 in the EU Is a Female. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/7896990/3-06032017-AP-EN.pdf/ba0b2ea3-f9ee-4561-8bb8-e6c803c24081 (accessed on 5 January 2019).

- Razavi, S. The 2030 Agenda: Challenges of Implementation to Attain Gender Equality and Women’s Rights. Gend. Dev. 2016, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAUW American Association of University Women. The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap. 2018. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596219.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Carral, P.; Alcover, C.M. Measuring Age Discrimination at Work: Spanish Adaptation and Preliminary Validation of the Nordic Age Discrimination Scale (NADS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, P.; Bodner, E.; Rothermund, K. Ageism: The Relationship between Age Stereotypes and Age Discrimination. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism; Ayalon, L., Tesch-Römer, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society of Human Resource Management. Hiring in the Age of Ageism. 2018. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0218/pages/hiring-in-the-age-of-ageism.aspx (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Stypinska, J.; Turek, K. Hard and Soft Age Discrimination: The Dual Nature of Workplace Discrimination. Eur. J. Ageing 2017, 14, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IZA Institute of Labor Economics. Population Ageing, Age Discrimination, and Age Discrimination Protections at the 50th Anniversary of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act. 2019. Available online: http://ftp.iza.org/dp12265.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Aaltio, I.; Salminen, H.; Koponen, S. Ageing Employees and Human Resource Management—Evidence of Gender-Sensitivity? Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2014, 33, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.L.; Newman, D.N.; McDaniel, J.R.; Buboltz, W.C. Gender Differences in Fear of Failure amongst Engineering Students. Int. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Axelrad, H.; Malul, M.; Luski, I. Unemployment Among Younger and Older Individuals: Does Conventional Data About Unemployment Tell Us the Whole Story? J. Labor Market. Res. 2018, 52, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TICAS The Institute for College Access&Success. 13th Annual Report Student Debt and the Class of 2017. 2018. Available online: https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy-files/pub_files/classof2017.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2019).

- Forbes. How to Use Employer Branding to Recruit Potential Employees. 2018. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescommunicationscouncil/2018/08/28/how-to-use-employer-branding-to-recruit-potential-employees/#62f953ad7548 (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Suen, H.Y.; Chang, H.L. Toward Multi-Stakeholder Value: Virtual Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISE (Institute of Student Employers). The Global Skill Gaps in the 21st Century. 2018. Available online: http://info.qs.com/rs/335-VIN-535/images/The%20Global%20Skills%20Gap%2021st%20Century.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- World Universities Ranking. Graduate Employability Ranking. 2019. Available online: https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings/employability-rankings/2019 (accessed on 15 February 2019).

- Coverdill, J.E.; Finlay, W. High Tech and High Touch: Headhunting, Technology, and Economic Transformation; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/books/140 (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. International Migration. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/wallchart/docs/MigrationStock2019_Wallchart.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Society of Human Resource Management. Average Cost-per-Hire for Companies Is $4,129, SHRM Finds. 2016. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/about-shrm/press-room/press-releases/pages/human-capital-benchmarking-report.aspx (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- TalentNow. Recruit Smarter. Faster. Recruitment Statistics. Trends and Insights in Hiring Talented Candidates. 2018. Available online: https://www.talentnow.com/recruitment-statistics-2018-trends-insights-hiring-talented-candidates/ (accessed on 4 January 2019).

- Gino, F.; Staats, B. Why Organizations Don’t Learn. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 110–118. Available online: https://hbr.org/2015/11/why-organizations-dont-learn (accessed on 6 January 2020).

- Center for Ageing Better. Becoming an Age-Friendly Employer. 2018. Available online: https://www.ageing-better.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/Becoming-age-friendly-employer.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Nottingham Trent University. New Migrants in the North East Workforce. Final Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.vonne.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/New%20Migrants%20in%20the%20NE%20Workforce%20Project%20Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Citigroup. Migration and the Economy. Economic Realities, Social Impacts and Political Choices, Citi GPS: Global Perspectives and Solutions. 2018. Available online: https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/reports/2018_OMS_Citi_Migration_GPS.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2019).

- Ghosh, K. Creative leadership for workplace innovation: An applied SAP-LAP framework. Dev. Learn. Organ. An. Int. J. 2016, 30, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, G.M.; Gallipoli, G. The Costs of Occupational Mobility: An Aggregate Analysis. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2018, 16, 275–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ERM European Restructuring Monitor Annual Report. Globalization Slowdown? Recent Evidence of Offshoring and Reshoring in Europe. 2017. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/ro/publications/executive-summary/2017/erm-annual-report-2016-globalisation-slowdown-recent-evidence-of-offshoring-and-reshoring-in-europe (accessed on 23 January 2019).

- IFR Robotics. Robots and the Workforce of the Future. 2019. Available online: https://ifr.org/downloads/papers/IFR_Robots_and_the_Workplace_of_the_Future_Positioning_Paper.pdf (accessed on 6 January 2020).

- Gartner Reports Fourth Quarter. Financial Results. 2018. Available online: https://investor.gartner.com/press-releases/press-release-details/2019/Gartner-Reports-Fourth-Quarter-2018-Financial-Results/default.aspx (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Latham, S.; Humberd, B. Four Ways Jobs Will Respond to Automation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 11–14. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/four-ways-jobs-will-respond-to-automation/ (accessed on 3 March 2019).

- Davenport, T.; Kirby, J. Only Humans Need Apply: Winners and Losers in the Age of Smart Machines, 1st ed.; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. 2016. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Foundation for Young Australians. The New Work Order. Report Series. 2017. Available online: https://www.fya.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/NWO_ReportSeriesSummary.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Mohem-Alizadeh, H.; Handfield, R.B. Developing Talent from a Supply-Demand Perspective: An Optimization Model for Managers. Logistics 2017, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte Insights. Accessing Talent: It’s More Than Acquisition. 2017. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/human-capital-trends/2019/talent-acquisition-trends-strategies.html (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- McKinsey&Company. Attracting and Retaining the Right Talent. 2017. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/attracting-and-retaining-the-right-talent (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- World Economic Forum. Migration Can Support Economic Development If We Let It. Here’s How. 2019. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/migration-myths-vs-economic-facts/ (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- ZipRecruiter. Even If Their Jobs Disappear, Manufacturing Workers Will Still Thrive. 2018. Available online: https://www.ziprecruiter.com/blog/manufacturing-workers-will-thrive/ (accessed on 28 February 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anastasiu, L.; Gavriş, O.; Maier, D. Is Human Capital Ready for Change? A Strategic Approach Adapting Porter’s Five Forces to Human Resources. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062300

Anastasiu L, Gavriş O, Maier D. Is Human Capital Ready for Change? A Strategic Approach Adapting Porter’s Five Forces to Human Resources. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062300

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnastasiu, Livia, Ovidiu Gavriş, and Dorin Maier. 2020. "Is Human Capital Ready for Change? A Strategic Approach Adapting Porter’s Five Forces to Human Resources" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062300

APA StyleAnastasiu, L., Gavriş, O., & Maier, D. (2020). Is Human Capital Ready for Change? A Strategic Approach Adapting Porter’s Five Forces to Human Resources. Sustainability, 12(6), 2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062300