Organizational Citizenship Behavior Motives and Thriving at Work: The Mediating Role of Citizenship Fatigue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) Motives and Citizenship Fatigue

2.2. The Mediating Role of Citizenship Fatigue

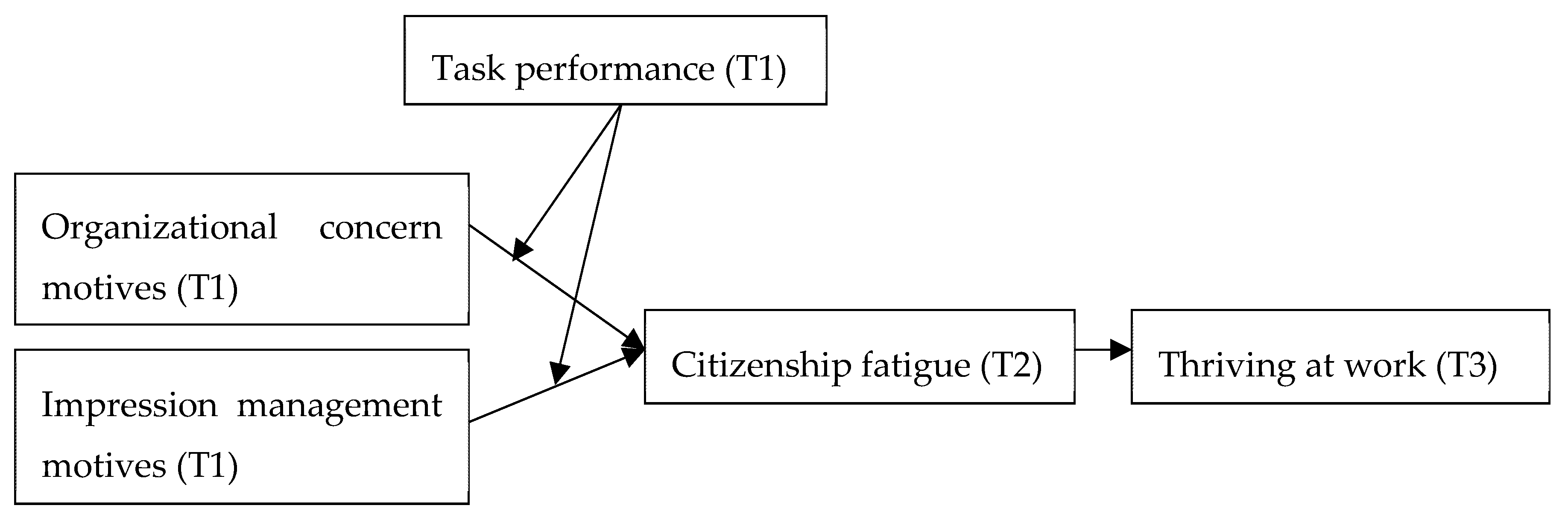

2.3. The Moderating Role of Task Performance

3. Research Method

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

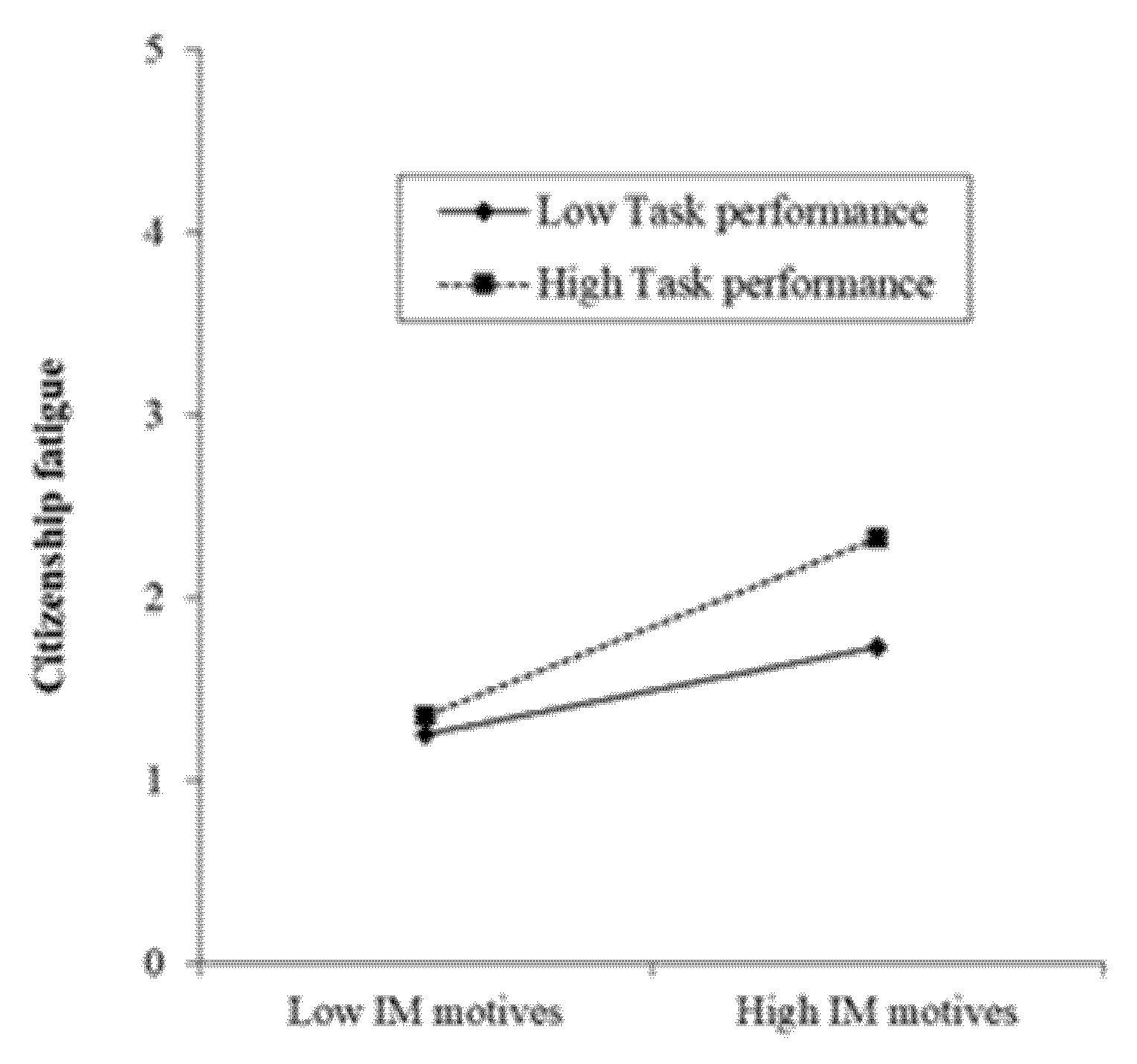

4.2. Tests of the Hypotheses

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paterson, T.A.; Luthans, F.; Jeung, W. Thriving at work: Impact of psychological capital and supervisor support. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Porath, C.L.; Gibson, C.B. Toward human sustainability: How to enable more thriving at work. Organ. Dyn. 2012, 41, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Porath, C. Creating sustainable performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 90, 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Elahi, N.S.; Abid, G.; Arya, B.; Farooqi, S. Workplace behavioral antecedents of job performance: Mediating role of thriving. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C.; Garnett, F.G. Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bal, P.M.; Akhtar, M.N.; Long, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z. High-performance work system and employee performance: The mediating roles of social exchange and thriving and the moderating effect of employee proactive personality. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resou. 2019, 57, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, B.; Ali, M.; Ahmed, S.; Moueed, A. Impact of managerial coaching on employee performance and organizational citizenship behavior: Intervening role of thriving at work. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2017, 11, 790–813. [Google Scholar]

- Trougakos, J.P.; Beal, D.J.; Cheng, B.H.; Hideg, I.; Zweig, D. Too drained to help: A resource depletion perspective on daily interpersonal citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: Recent trends and developments. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psycho. Organ. Behav. 2018, 80, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books/DC Heath and Company: Lexington, KY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, X.; Ni, J. The impact of transformational leadership on employee sustainable performance: The mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R. The roles of OCB and automation in the relationship between job autonomy and organizational performance: A moderated mediation model. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 1139–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Mishra, P. Effects of organizational citizenship behaviors on selection decisions in employment interviews. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koopman, J.; Lanaj, K.; Scott, B.A. Integrating the bright and dark sides of OCB: A daily investigation of the benefits and costs of helping others. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Skouloudis, A. Revisiting the relationship between corporate social responsibility and national culture. Manag. Decis. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G.; Skouloudis, A. National CSR and institutional conditions: An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudis, A.; Isaac, D.; Evaggelinos, K. Revisiting the national corporate social responsibility index. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World 2016, 23, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudis, A.; Evangelinos, K. A research design for mapping national CSR terrains. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 2012, 19, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudis, A.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Malesios, C.; Evangelinos, K. Priorities and perceptions of corporate social responsibility. Manag. Decis. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, E.Y.; Jung, H.; Park, I.-J. Psychological factors linking perceived CSR to OCB: The role of organizational pride, collectivism, and person–organization fit. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J.J. What motivates OCB? Insights from the volunteerism literature. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, S.W.; Meglino, B.M.; Korsgaard, M.A. The role of other orientation in organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, E.G.; Snyder, M.; Ridge, R.D.; Copeland, J.; Stukas, A.A.; Haugen, J.; Miene, P. Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Midili, A.R.; Kegelmeyer, J. Beyond job attitudes: A personality and social psychology perspective on the causes of organizational citizenship behavior. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X. How Responsible Leadership Motivates Employees to Engage in Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Double-Mediation Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, S.M.; Penner, L.A. The causes of organizational citizenship behavior: A motivational analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Bowler, W.M.; Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H. Organizational concern, prosocial values, or impression management? How supervisors attribute motives to organizational citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 1450–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, R.; Bolino, M.C.; Lin, C.-C. Too many motives? The interactive effects of multiple motives on organizational citizenship behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2002, 6, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Klotz, A.C.; Turnley, W.H.; Harvey, J. Exploring the dark side of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Hsiung, H.-H.; Harvey, J.; LePine, J.A. “Well, I’m tired of tryin”! Organizational citizenship behavior and citizenship fatigue. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. J. Pers. 1995, 63, 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nix, G.A.; Ryan, R.M.; Manly, J.B.; Deci, E.L. Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 35, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, A.C.; Bolino, M.C.; Song, H.; Stornelli, J. Examining the nature, causes, and consequences of profiles of organizational citizenship behavior. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C. Citizenship and impression management: Good soldiers or good actors? Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F.; Ciarocco, N.J. Self-regulation and self-presentation: Regulatory resource depletion impairs impression management and effortful self-presentation depletes regulatory resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Kacmar, K.M.; Turnley, W.H.; Gilstrap, J.B. A multi-level review of impression management motives and behaviors. J. Manage. 2008, 34, 1080–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Porath, C. Self-Determination as Nutriment for Thriving: Building an Integrative Model of Human Growth at Work; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Building sustainable organizations: The human factor. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Neveu, J.-P.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Westman, M. Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Klotz, A.C.; Turnley, W.H. The unintended consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors for employees, teams, and organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior; Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Podsakoff, N.P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, P.V.; Kleinmann, M.; König, C.J.; Melchers, K.G. Transparency of Assessment Centers: Lower Criterion-related Validity but Greater Opportunity to Perform? Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 467–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Koch, S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L. The effect of causality orientations and positive competence-enhancing feedback on intrinsic motivation: A test of additive and interactive effects. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2015, 72, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.; Hyatt, D.; Benson, J. Consequences of the performance appraisal experience. Pers. Rev. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Pierce, J.R. Effects of task performance, helping, voice, and organizational loyalty on performance appraisal ratings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.-H.; Rosen, C.C. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, H.K.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Lee, C. Workplace ostracism and employee creativity: An integrative approach incorporating pragmatic and engagement roles. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonner, W.J.; Berry, J.W. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.M.; Mayer, D.M. Good soldiers and good actors: Prosocial and impression management motives as interactive predictors of affiliative citizenship behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.M.; Berg, J.M.; Cable, D.M. Job titles as identity badges: How self-reflective titles can reduce emotional exhaustion. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1201–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Cunningham, W.A.; Shahar, G.; Widaman, K.F. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D.; Rhemtulla, M.; Gibson, K.; Schoemann, A.M. Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Methods 2013, 18, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D.J.; Preacher, K.J.; Gil, K.M. Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2006, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selig, J.P.; Preacher, K.J. Monte Carlo Method for Assessing Mediation: An Interactive Tool for Creating Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects. Available online: http://quantpsy.org/medmc/medmc111.htm (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Lin, C.-C.T.; Peng, T.-K.T. From organizational citizenship behaviour to team performance: The mediation of group cohesion and collective efficacy. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2010, 6, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Ter Hoeven, C.L.; Bakker, A.B.; Peper, B. Breaking through the loss cycle of burnout: The role of motivation. J. Occu. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Shi, J. Linking ethical leadership to employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: Testing the multilevel mediation role of organizational concern. J. Bus. Ethics. 2017, 141, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Larson, R. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.J.; Savani, K.; Ilies, R. Doing good, feeling good? The roles of helping motivation and citizenship pressure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kwantes, C.T.; Karam, C.M.; Kuo, B.C.; Towson, S. Culture’s influence on the perception of OCB as in-role or extra-role. Int. J. Int. Rela. 2008, 32, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euwema, M.C.; Wendt, H.; Van Emmerik, H. Leadership styles and group organizational citizenship behavior across cultures. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 1035–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequencies | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 162 | 46.42 |

| Female | 187 | 53.58 |

| Age | ||

| < 25 | 99 | 28.37 |

| 25–35 | 176 | 50.42 |

| 36–45 | 58 | 16.62 |

| 46–55 | 15 | 4.30 |

| > 55 | 1 | 0.29 |

| Education | ||

| Under bachelor’s degree | 203 | 58.17 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 110 | 31.52 |

| Master’s degree and above | 36 | 10.32 |

| Tenure | ||

| Under 3 years | 225 | 64.47 |

| 4–10 years | 105 | 30.09 |

| Over 10 years | 19 | 5.44 |

| Model | Variables | χ2 | df | Δχ2/Δdf | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five factors | OCM, IMM, TP, CF, WT | 386.96 | 160 | — | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.96 |

| Four factors | OCM+IMM, TP, CF, WT | 876.50 | 164 | 489.54/4 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.86 |

| Three factors | OCM+IMM+TP, CF, WT | 1494.08 | 167 | 1107.12/7 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.74 |

| Two factors | OCM+IMM+TP+CF, WT | 2497.15 | 169 | 2110.19/9 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.55 |

| One factor | OCM+IMM+TP+CF+WT | 2769.70 | 170 | 2382.74/10 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.50 |

| Variables | M | s.d. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender b | 0.54 | 0.50 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2. Education c | 1.52 | 0.68 | 0.13* | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3. OC motives (T1) | 4.34 | 0.66 | −0.02 | −0.08 | (0.92) | - | - | - | - |

| 4. IM motives (T1) | 3.24 | 0.98 | −0.06 | −0.14** | 0.15** | (0.91) | - | - | - |

| 5. Task performance (T1) | 3.87 | 0.81 | −0.09 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.11* | (0.92) | - | - |

| 6. Citizenship fatigue (T2) | 2.46 | 1.00 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.11* | 0.38** | 0.21** | (0.95) | - |

| 7. Thriving at work (T3) | 4.12 | 0.62 | −0.05 | −0.05 | 0.35** | 0.08 | −0.01 | −0.22** | (0.84) |

| Variables | Citizenship fatigue (T2) | Thriving at work (T3) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.66***(0.46) | 4.62***(0.12) |

| Gender b | −0.12(0.10) | −0.08(0.07) |

| Education c | −0.06(0.07) | −0.06(0.05) |

| OC motives (T1) | −0.25***(0.07) | |

| IM motives (T1) | 0.37***(0.05) | |

| Task performance (T1) | 0.22**(0.07) | |

| OC motives X Task performance | −0.04(0.07) | |

| IM motives X Task performance | 0.16*(0.08) | |

| Citizenship fatigue (T2) | −0.14***(0.03) |

| Independent Variables | Moderator: Task Performance | Path a | Path b | Effect | 95% CI a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effects | |||||

| OC motives | −0.25***(0.07) | −0.14***(0.03) | 0.04**(0.01) | [0.02, 0.06] | |

| IM motives | 0.37***(0.05) | −0.14***(0.03) | −0.05***(0.01) | [−0.08, −0.03] | |

| Conditional indirect effects | |||||

| IM motives | Low (−1 SD) | 0.24**(0.08) | −0.14***(0.03) | −0.04*(0.01) | [−0.06, −0.02] |

| High (+1 SD) | 0.50***(0.08) | −0.14***(0.03) | −0.07***(0.02) | [−0.11, −0.04] | |

| Difference | −0.04*(0.02) | [−0.07, −0.00] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, Y.; Lou, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Motives and Thriving at Work: The Mediating Role of Citizenship Fatigue. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062231

Qiu Y, Lou M, Zhang L, Wang Y. Organizational Citizenship Behavior Motives and Thriving at Work: The Mediating Role of Citizenship Fatigue. Sustainability. 2020; 12(6):2231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062231

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Yang, Ming Lou, Li Zhang, and Yiqin Wang. 2020. "Organizational Citizenship Behavior Motives and Thriving at Work: The Mediating Role of Citizenship Fatigue" Sustainability 12, no. 6: 2231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062231

APA StyleQiu, Y., Lou, M., Zhang, L., & Wang, Y. (2020). Organizational Citizenship Behavior Motives and Thriving at Work: The Mediating Role of Citizenship Fatigue. Sustainability, 12(6), 2231. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062231