Abstract

Business incubators create value by combining the entrepreneurial spirit of start-ups with the resources that are typically available to new businesses. It is widely recognized that knowledge-based entrepreneurial companies are the main creators of economic growth, and such enterprises require special business development services. Therefore, the study aims to examine the role of business incubators in providing greater services (networking services, capital support, and training programs) in entrepreneurship development. Secondly, it also examines the mediating and moderating role of business start-up and government regulations for entrepreneurship. Using a quantitative methodology, we examine 567 samples through structural equation modeling. We find that the business incubators are playing an effective mediating role in providing networking services, capital support, and training programs to individuals and entrepreneurs, which are significant for entrepreneurship development, whereas business start-up positively mediates the relationship between networking services, capital support, training programs, and entrepreneurship development. Government regulations for entrepreneurship have a direct effect on entrepreneurship development. More importantly, government regulations for entrepreneurship have a positive moderating effect between business start-up and entrepreneurship development. Our study identifies the critical resources needed to improve the quality of business incubators and to ensure the availability of such resources to improve entrepreneurship development.

1. Introduction

The present study is being carried out in Pakistan, which is a developing country and the sixth-largest country in terms of population, with 2.55% of the world’s overall population. It is worth noting that Pakistan’s population is important because its core parts are still young [1]. According to the total population report, in Pakistan, 60% of young people are under 30 years. However, the majority of the population in the country is poor and unemployed, as the country’s daily income is less than USD 1.25, indicating that poverty in Pakistan is increasing. An economic survey shows that 24.3% of Pakistanis live below the poverty line [1]. Most repugnant about this situation, which worsens every year, is that in the long run it will prove a threat to Pakistan’s economy [2]. Unemployment is one of the most common obstacles to sustained and viable economic growth. The increasing rate of unemployment is the same among professional degree holders and other labor force. The Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 2018 shows that Pakistan’s labor force input rate is 54.4%. According to these statistics, 3.7 million people were unemployed from 2017 to 2018 [3,4]. A large amount of the labor force steadily increases, and also the increase in joblessness continues; therefore, new employment opportunities should also be created. [5].

The Economic Survey of Pakistan shows a 5.6% unemployment rate in Pakistan, which encourages street crime, unemployment, and corruption. One of the reasons why entrepreneurial activities are not progressing is due to the lack of participatory conditions. It can be avoided if students acquire business training that will enhance their business skills, attitude, and knowledge. Such skills and knowledge increase not only self-employment but also employers’ work [6]

To maintain a stable economy, the government needs to promote entrepreneurship because of entrepreneurship’s contribution to developing and developed countries and advanced economies. The literature suggests that substantial economic growth should be linked to entrepreneurs who use state investment for knowledge creation. Entrepreneurship is a key source of economic revolution, job creation, and business development; hence, it is pivotal to attract the young and educated to become entrepreneurs. According to Schumpeter, entrepreneurs are willing and able to turn new ideas or inventions into successful innovations. The idea that entrepreneurship leads to economic growth is one explanation of the remaining parts of the theory of endogenous growth, so it continues to be debated in academic economics [7]. Nowiński and Haddoud [8] reported that in the field of entrepreneurship, a key attribute that needs to take root in every new venture is the intention to start a business. Thus, entrepreneurial intention concerns the individual’s attitude towards starting a new business. They further explored that entrepreneurship is even more suitable once there are fewer jobs in the labor market. Storey [9] found that knowledge of entrepreneurship will be beneficial when new graduates cannot find their ideal jobs or fall back when the economy slows, forcing some new graduates to turn to entrepreneurship. Also, Akinbola, et al. [10] claim that students’ propensity for entrepreneurship is an essential framework for forming a business start-up. Students’ attitudes, behavior, and entrepreneurial compassion may encourage the intention and desire to launch new business activities in the future. Students trained in educational institutions or in incubators are on the way to becoming initiators of successful entrepreneurs. Therefore, the concept of the business start-up among students is a vibrant field that has to be further discovered in order to understand and appreciate the practice of starting new businesses [11].

Another educational program recognized by various higher educational institutions to promote entrepreneurship is the business incubation program. Business incubation can provide resources for start-ups such as networking services, office space, training programs, consultancy, and other essential services, but it also aims to promote intranets and knowledge transfer between start-ups. The tendency towards entrepreneurial behavior can be positively influenced by several aspects such as business incubators and internships [12]. The existence of a business incubator in a higher education institution is vital to support and assist primarily students who have a business to be able to expand and advance their business activities. In addition, business incubators also help motivate new entrepreneurs to turn their business ideas into real businesses. In order to assess the possible benefits of a business incubator (BI), it is essential to explore the effects of services provided by the business incubators on entrepreneurship development [13].

In Pakistan, there are many universities, including public and private universities, that offer courses in different specialties. Some of these institutions help provide inventive business ideas and reduce unemployment. Graduates of limited universities in Pakistan are less competitive than foreigners. Still, start-ups are in full supply; nevertheless, Pakistan even now suffers from the shortage of capital, and the value of getting capital from nongovernmental sources is very high because of their grasping nature. In addition, entrepreneurs here lack the entrepreneurial skills and financial support needed to successfully conduct business in this globally competitive business environment [14]. As a way of guiding strong economic growth, the number of incubators around the world is increasing, so governments and other agencies that support these incubators are paying more attention to assessing their performance [15].

There are a large number of university students in various fields of expertise in Pakistan. Some of them have excellent, innovative, and appropriate ideas, which can serve as development tools to support a weak economy and reduce unemployment. These business ideas show high potential for success if they are provided with logistics and financial support. The majority of Pakistani business people cannot market their ideas or get the funding they need. They do not even have the required set of business skills, though they have the required information [16].

Over time, it was gradually recognized that innovations and entrepreneurship are most important to boosting Pakistan’s economic growth. Therefore, measures are being taken to extend science and technology initiatives to improve the economy. The efforts to establish the environment of venture creations and their success gave birth to business incubators in Pakistan [17]. There is a considerable research gap in this research area, especially in Pakistan. This study attempts to contribute to the incubation literature by examining the role of business incubators and the mediating and moderating role of business start-up and government regulations for entrepreneurship in entrepreneurship development.

The following sections of this article discuss the development of hypotheses, followed by the research methods section, which provides detailed information about the research design, sampling, data collection tools, measurement scales, and analysis process and concludes with a description of the data analysis and results. This section shows a discussion of the theoretical and practical implications of the research. In the section, the limitations of the study and future research direction are highlighted. Finally, in the conclusion section, the overall conclusions of the study are discussed.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Role of Business Incubators in Entrepreneurship Development

Researchers have proposed various entrepreneurial theories. For example, Schumpeter, in 1949, defined the entrepreneur as a person who initiates and helps sustain the development process through the circular flow of the economy. In contrast, the economic theory of entrepreneurship says that entrepreneurship can be successful only when the economic environment is favorable, and some studies have proposed an exposure theory of entrepreneurship, that is, exposure to new opportunities and ideas will lead to the creation of entrepreneurial activities in the economy [18].

Mahmood, Jamil and Yasir [17] report that business incubation provides one of the most effective strategies to promote community entrepreneurship, to support job creation by supporting new business schemes and by promoting diversification of business opportunities. It stimulates growth and acts as an agent, revitalizes rural or impoverished areas and promotes the transition to business ownership for students and workers seeking new career paths. Business incubators can focus on business space with low-cost and multiple business services to assist entrepreneurs in the early stages of business development [19]. Campbell [20] believes that business incubators also provide opportunities to integrate education and training, focusing on entrepreneurship, business, management, new skills needed at work, and training of small company employees involved in business incubation or community. While measuring the performance of business incubators, it is revealed in the literature that evaluating BI performance is a complicated procedure because there is no single standard for doing this. Second, most studies in the above literature relate to the performance of incubators in developed countries and very less in developing countries [21]. Eshun [22] has suggested that government efforts should also be incorporated to assess the business incubator’s performance.

Kwapisz [23] point out that Government policy related to entrepreneurial practices is aimed at encouraging entrepreneurship by creating an environment that is profitable for entrepreneurs. This is possible through the implementation of guidelines that would regulate entrepreneurial activities in general because entrepreneurship is the foundation of the state path to industrial development. Saberi and Hamdan [24] argue that there is a need for government regulation because entrepreneurship should be successfully implemented, regardless of the administration in power, in order to achieve the guiding objectives which are often continuously lacking.

Therefore, we proposed an innovative conceptual model to explore the role of business incubators as a tool for entrepreneurship development: the mediating and moderating role of business start-up and government regulations in entrepreneurship development.

2.2. Network Services

Exposure to entrepreneurial development opportunities is a form of integrating the work of preparing entrepreneurs to build successful businesses. This experience can be facilitated through formal or informal connections with key players and institutions in the community. This process requires more active participation in strategic planning, broad community partnerships, and support for network activities [25]. Networking services consist of a set of relationships with various agents or organizations. These can provide critical resources for a critical company [26]. The ability to access online resources is critical for start-ups [27]. Mort and Weerawardena [28] define the company’s capabilities, such as the ability to initiate, maintain, and leverage associations with various external allies. According to Mort and Weerawardena [28], relationships are also crucial sources of understanding customer needs so that companies can develop marketable products. They found that the performance of institute affiliates was significantly affected by their network abilities. Torkkeli, et al. [29] found that networking capabilities help develop knowledge-intensive products that enable companies to identify and take advantage of performance opportunities in global markets.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Business incubators providenetwork services that have a positive effect on entrepreneurship development.

2.3. Capital Support

In the 1990s, capital support became a new source of financing for technological innovation in the private sector. Especially in the U.S., many small high-tech start-ups outside Silicon Valley and Boston get money from venture capital funds. In recent years, capital support has begun to play a progressively vital role in Europe and Asian countries [30]. Capital support is seen as a key source of innovation, employment, and economic growth, so policymakers need to pay attention to entrepreneurship and capital support [31]. Bonini and Capizzi [32] define capital support as the synonym of innovation, venture capital, and financing for start-ups and start-ups seeking rapid growth in the 20th century. Data from the 2016 Entrepreneur’s Annual Survey shows that only 5% to 10% of paid employees do not need to raise capital when starting a business. So, 90% to 95% of entrepreneurs need a certain amount of financing to start a business. These hurdles and the lack of capital suitable for various new businesses mean that there is a large number of unmet needs among entrepreneurs who need capital, and entrepreneurs often cannot choose the financing services that best suit their business [33]. Khan, et al. [34] points out that entrepreneurs and researchers often quote a lack of access to capital as a significant hindrance facing many entrepreneurs. To understand the role of access to capital in entrepreneurship, further research should be conducted.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Business incubators provide capital support that has a positive effect on entrepreneurship development.

2.4. Training Programs

Business incubators play a crucial role in creating and promoting some technology-intensive enterprises. These organizations often lack the required skills for business survival, so second-generation incubators begin to offer knowledge-based services and long-term use of physical infrastructure [35]. Alpenidze and Sanyal [36] found that providing training and mentoring services is an essential service for business incubators. These services are considered necessary for continuous learning and skill development and, ultimately, excellence. A previous study conducted [37] to assess the performance of business incubators concluded that they provide business support services to clients, which may include training, mentoring, access to funding, etc. The best thing for them is that they provide tailor-made services according to the requirements of each entrepreneur. According to Hernandez-Gantes, Sorensen and Nieri [25], consulting services are classified in the third rank, while education and training is generally the least significant attention. On the other hand, once entrepreneurs realize the intricacy of leading a business, the importance and need for consulting, training and education opportunities increase significantly.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Business incubators provide training programs that have a positive effect on entrepreneurship development.

2.5. Business Start-Up

The term “start-up” is created for business models that use technology. A start-up is a technology-based company that uses the added value of combined technologies to provide new products or services. This is defined as “innovation through technology.” Start-ups use a scalable business model, that is, a start-up invests in improving the technology on which its project is based, and once the technology is improved, it creates a product or service [25]. Business startup is crucial in order to create new jobs and bring competitive dynamics into the business environment. Start-up companies are thus those that have ambition and potential to become gazelles that can, with fast growth, create a large number of new jobs. They also contribute to promote entrepreneurship and introduce values of proactivity into society [38]. Arafat, et al. [39] proclaimed that the intention to start a new business usually depends on three perspectives: personal perspective (understanding existing entrepreneurial skills), economic opportunity perspective and networking services. However, an environment in which firms get the support of facilities and assistance related to opportunities and threats in the early stage of the venture falls in a range of business incubators. According to Khan, Arafat, Raushan, Saleem, Khan, Khan and Entrepreneurship [34], new companies that aim to gain a competitive advantage and create value are bound to cultivate their intellectual capital, which can be in the form of knowledge, brands, patents and trademarks, customer relationships, human capital, and research and development. Most entrepreneurs have acquired diverse network resources through education or work experience, which is very valuable for their enterprises in the critical start-up stage. It is often difficult to obtain financial resources from private investors because early-stages venture capital is generally considered a high-risk project [40].

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Business start-up has a positive effect on entrepreneurship development.

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Government regulations for entrepreneurship have a positive effect on entrepreneurship development.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Business start-up mediates the relationship between networking services and entrepreneurship development.

Hypothesis 7 (H7):

Business start-up mediates the relationship between capital support and entrepreneurship development.

Hypothesis 8 (H8):

Business start-up mediates the relationship between training programs and entrepreneurship development.

2.6. Government Regulations for Entrepreneurship

A study based on 39 countries [41] investigates the relationship between entrepreneurship and regulations. The study found that the minimum capital required to establish a business decreases the entrepreneurship rate across the countries, likewise the labor market regulations. Moreover, the administrative concerns of establishing a business, such as cost, time, and a number of processes required, are irrelevant to the creation rate of new business. The government policies and actions related to businesses are essential factors to the heterogeneity of the outside environment in which entrepreneurship activities reside and are part of social embeddedness [42]. Michael and Pearce [43] point out that the aims of government vary in countries, as some countries’ governments support entrepreneurship to generate jobs, others to create competition in the market and innovation. To boost the innovation process, the government should improve the policies that support the creation of new business and concentration of residuals claims. They cite inconsistent government policies as one of the challenges facing entrepreneurs. In addition, [44] finds that the main barriers towards entrepreneurship development are lack of infrastructure development such as transport, innovative, financial, managerial and logistical. Hence, it is recommended that government regulations have to be improved for significant effects on small businesses.

Hypothesis 9 (H9):

Government regulations for entrepreneurship positively moderate the relationship between the business start-up and entrepreneurship development.

3. Research Methodology

The research methodology that was used in this study is quantitative. This method is used to measure the problem statement by generating numerical data or data that can be converted into useful statistics. It is used to measure views, opinions, and other defined variables and to generalize results from a larger sample population. To a lesser extent, the quantitative method examines and analyzes in order to clarify the research objects and questions they are appropriate to or not.

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

In this research, the technique of purposive sampling was employed to collect information to achieve the objective of the research. Our research sample consists of men and women living in five provinces of Pakistan. While considering the importance of the present study, data were collected from four major provinces of Pakistan, namely: Punjab, Sindh, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, and Baluchistan. The reason behind this was that their respondents had relevant information. We believe that they are the group that best represents the entrepreneurial characteristics of the present Pakistani society. For the following reasons, we had no specific concerns in choosing these four cities. The appropriate respondents were individuals from undergraduate and graduate schools who have studied in entrepreneurship training programs, and are currently participating in entrepreneurial activities and working with small and medium enterprises. The purposive sampling is also called judgmental sampling; it involves only those respondents who provide accurate and relevant information. The study used a survey method to gather data from the respondents, and the survey questionnaires were circulated with the help of field assistants [45]. All provinces were selected given the fact that all respondents have similar characteristics [46]. The selected respondents were considered as the most appropriate key informants because they are well informed about entrepreneurial activities, therefore, would respond to the survey accurately [47]. To ensure that nonresponse bias was not a major concern in this study, an independent sample t-test was performed following [48] suggestion. Specifically, respondents were divided into two groups based on those who responded to the first follow-up (early responders) and those who responded after the third follow-up (late responders). We assumed that those who responded after the third follow-up were most similar to non-respondents [48]. The reliability and validity analysis was done on all scales to assess the degree of internal consistency among variables, which was interpreted as Cronbach’s alpha, as presented in table 2, in the results section. The analysis was done using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling. The response rate of the study was 567/630 = 0.9 * 100 = 90.0%.

Table 1 indicates the demographical information of respondents. It specifies that 494 (87.1%) of the population involved male respondents, while 73 (12.8%) were females. Furthermore, 267 (47.0%) of the population fell into the age range of 31–40 years. Middle management comprised 386 (68.0%) of the respondents having jobs that come under the middle management level. Similarly, 300 (52.9%) of respondents had work experience of 6–10 years.

Table 1.

Respondents information.

3.2. Measurement Scales

This section briefly defines the items used in the study and discusses the development of measures employed in survey instruments. The present study adopted a well-established and widely used scale. However, the items were modified as per the objective of the study. All of the scale was based on the five-point Likert scale, where 1 represents strongly disagree, and 5 represents strongly agree as shown in Appendix A.

3.2.1. Entrepreneurship Development

To measure entrepreneurship development, we adopted four items from the study of [49], and one item from the past study [50].

3.2.2. Networking Services

In order to measure networking services, three items were borrowed from the study [17], whereas two were adopted from [50]. These items were employed for assessing the access to network services provided by business incubators to incubates.

3.2.3. Capital Support

In order to measure capital support, this study borrowed five measurement scales used in the previous study. The scale for capital support borrowed from the study [51].

3.2.4. Training Programs

We adopted five items related to training programs used in the previous study [17]. This scale was used to assess the effects of training programs provided by business incubators

3.2.5. Business Start-Up

In this study, we define business start-up as the actual start-up of a new business. In order to measure business start-up, two items obtained from the past study [50], and five items obtained from the previous studies [52].

3.2.6. Government Regulations for Entrepreneurship

To measure the government regulations for the entrepreneurship 5 items were adapted from the work of [53]. Hence, all of the items taken were more popular and widely used by other scholars.

3.3. Data Analysis

The most widely accepted and newest techniques nowadays are partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) and the techniques used in it [54,55]. The results of this study are based on PLS-SEM 3.2.7. The preference for using this software involved the overall attractiveness and suitability of its application [56]. Furthermore, it involves comprehensive information about variables, per Hair, et al. [57]. Also, the PLS method is considered a well-recognized approach of SEM, per McDonald [58].

The present study used PLS path modeling for the data analysis because of its widespread application in academic research [59]. Before testing the individual items and internal consistency, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and structure paths, various assumptions of normality and multicollinearity, common method bias were assessed [60]. The present study used a two-step process, which was (1) an assessment of the measurement model; and (2) an assessment of the structural model for evaluating and reporting PLS-SEM results [61,62], besides an assessment of the structural model witnessed by R2 and Q2.

4. Results

For analysis of the results, partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized. Several tests related mainly to reliability, validity, and path coefficients, as well as to ensure that the data were free from multicollinearity and other data-related bias were measured [63]. This analysis section used a two-way approach to assess the results.

(1) Assessment of measurement model, and (2) Structural model [63,64].

4.1. An Assessment of the Measurement Model

As per [64] suggestions in order to measure the model of study, scholars are required to assess the “individual item reliability, internal consistency, content validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.”

4.1.1. Individual Item Reliability

Measured by taking into account the outer loadings of items related to particular constructs [65]. [66] recommended that it should be retained between 0.40 and 0.70, while [67] proposed that it should exceed 0.5. Hence, as demonstrated in Table 2, all the values of items of six constructs adequately satisfied and met the standard, item values noted in the range of 0.525 to 0.915.

Table 2.

Measurement of Model.

As per the rule of thumb set by (Nunnally 1978), the value of Cronbach’s Alpha should be greater than 0.7. As displayed in Table 2, the values of Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) fell in the range of 0.728 to 0.939. Hence, as per the results found in Table 2, Cronbach’s Alpha of capital support was 0.91, and composite reliability was 0.933. Entrepreneurship development yielded Cronbach’s Alpha range of 0.939 to 0.954 for composite reliability. Whereas, Cronbach’s Alpha range for government regulations for entrepreneurship was 0.728 to 0.811. Meanwhile, networking services had a 0.878 Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability 0.913. Also, a business start-up found with 0.91 Cronbach’s Alpha and 0.933 composite reliability. The training programs had a 0.906 Cronbach’s Alpha and composite reliability of 0.93. Thus, all variables in the study were found within a range of 0.7 to 0.9, categorized by Hinton [68]. About the average value extracted, it should be greater than 0.5 [69].

4.1.2. Internal Consistency Reliability

Rule of thumb states that the value of composite reliability should be equivalent to or higher than 0.7. Table 2 reflects the coefficient value of composite reliability (CR) of the constructs, as displayed in the table, its value falls in the range of 0.811 to 0.954, suggesting the adequate reliability of the measures.

4.1.3. Convergent Validity

As per the rule of thumb, the value of average value extracted (AVE) should be equivalent to 0.5 or above. The value of AVE of the present study, as reflected in Table 2, falls in the range of 0.569 to 0.805. Henceforth, it was concluded that this study demonstrated a satisfactory level of convergent validity.

4.1.4. Discriminant Validity

Two methods were used to evaluate the “discriminant validity” of the variables. (1) It was ensured that the cross-loadings of indicators should be higher than any other opposing constructs [56]. (2) According to the criterion, the square root of AVE for each construct should exceed the inter-correlations of the construct with other model constructs. Hence, as reflected in Table 3, both approaches ensured the satisfaction of the results and validity. Therefore, it could be concluded that all the constructs utilized in the current study had a sufficient level of discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Latent variable correlation and the square root of average variance extracted.

4.2. An Assessment of the Structural Model

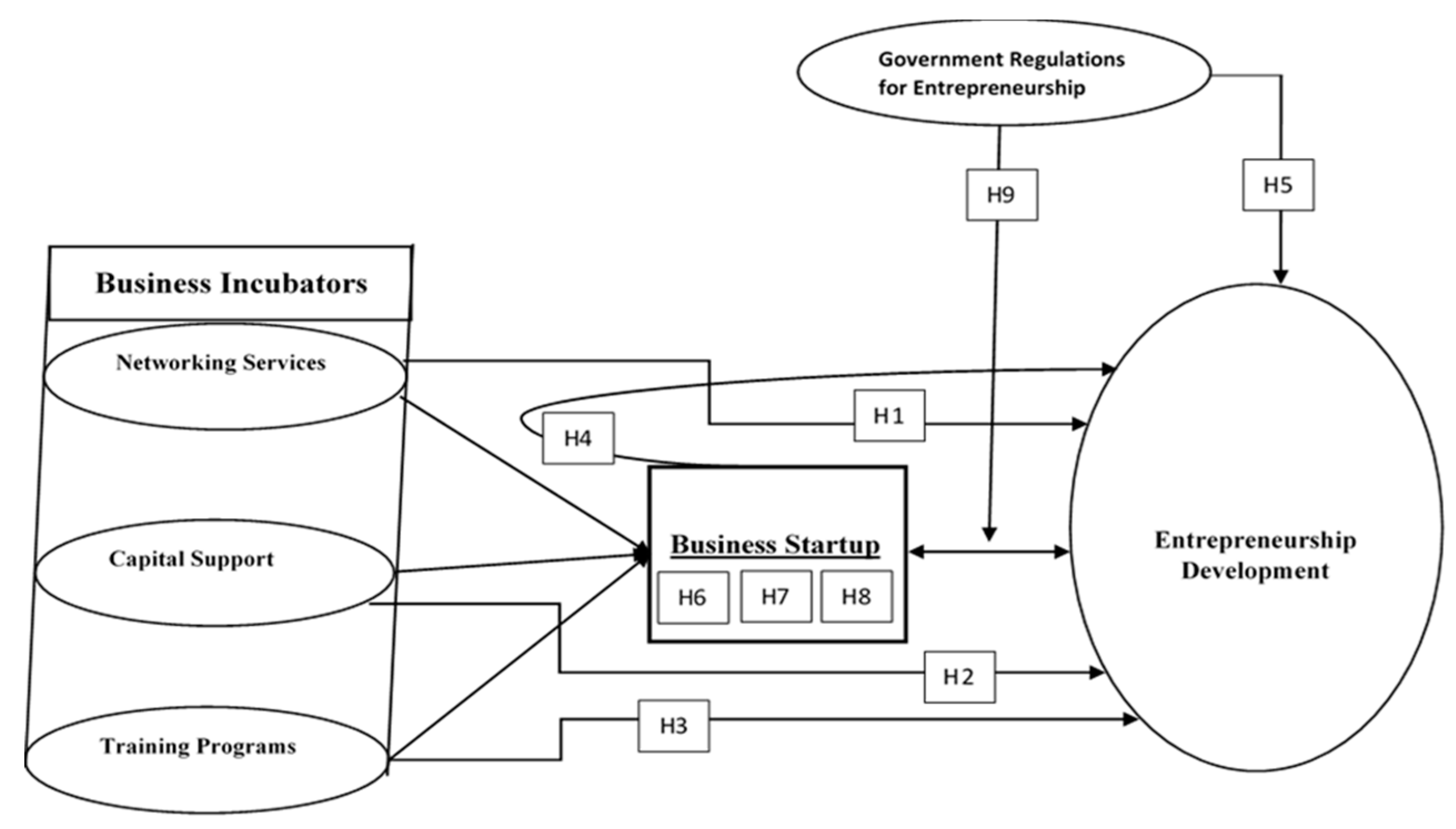

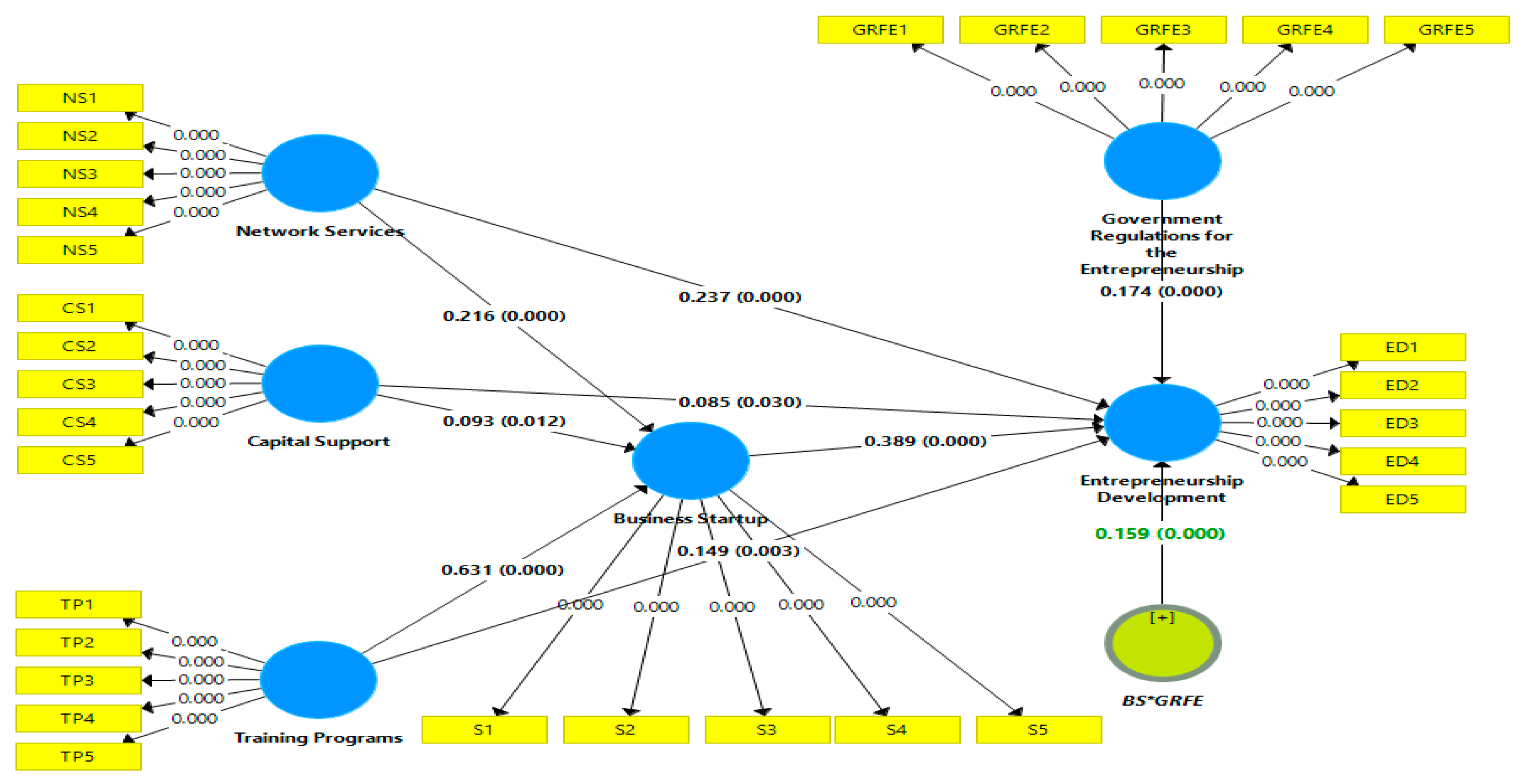

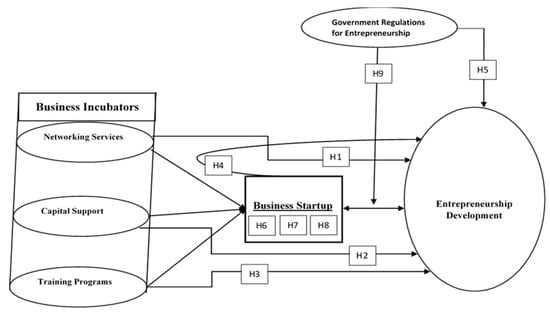

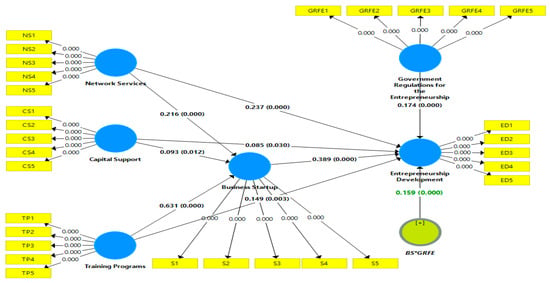

This article utilized PLS bootstrapping with 600 bootstraps and 567 cases with the motive to enlighten the path coefficients and their significance [64]. Figure 1, Figure 2 and table 6 demonstrate the comprehensive depiction of evaluations of the structural model alongside statistics related to moderation of government regulations for entrepreneurship.

Figure 1.

Joo Model of entrepreneurship development.

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Modelling (Path coefficient and p-value).

In order to evaluate the variance of the measures, PLS-SEM suggests evaluating the R2 coefficient, which also called the coefficient of determination [57]. According to [70], the values of R2 were 0.60, 0.33, and 0.19, respectively, set as a rule of thumb, and these values were described as substantial, moderate and weak. In contrast, the values of 0.75, 0.5, and 0.25, respectively, were set as a rule of thumb [64]. [63], proposed that the R2 coefficient is subject to the situation where a specific study is conducted. However, as per [71], the recommendation of an R2 coefficient of 0.10 was also acceptable. Meanwhile, as reflected in Table 4, the present study R2 noted was 0.588. This proposes that network services, capital support, training programs, business start-up and government regulations for entrepreneurship define 58.8% of the variance in entrepreneurship development. According to [67], the suggestion of the obtained value of R2 is moderate.

Table 4.

Strength of model.

4.2.1. Predictive Relevance of the Model

Keeping in view the reflective nature of measures, this study employed cross-validated redundancy measure Q2 for evaluating the model as per suggestions of [72]. It is an indicator of the model’s out-of-sample predictive power or predictive relevance given by [73,74] Q2 value. In the structural equation model, Q2 values larger than zero for a specific reflective endogenous latent variable indicate the path model’s predictive relevance for a particular dependent construct. Hence, as reflected in Table 5, the results of the study show that the model has predictive relevance.

Table 5.

Cross-validated redundancy.

4.2.2. Testing Hypotheses

Table 6 shows the analysis of construct hypotheses, including their beta value, mean, standard deviation as well as t and p-value. Hence, the decision was taken based on p-value 0.05.

Table 6.

Path coefficients and hypotheses testing.

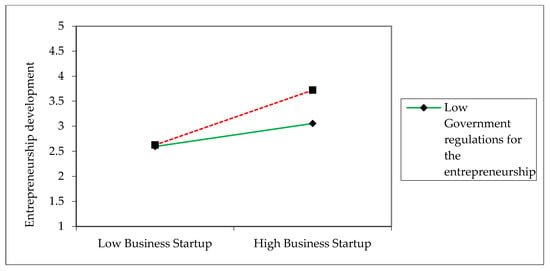

The product indicator techniques utilizing PLS-SEM were administered in the present study for identifying and assessing the power of the moderating effect of government regulations for entrepreneurship on the business start-up and entrepreneurship development relationship [75]. This study employed a product indicator method because the suggested moderating construct was continuous [76]. Furthermore, rules were used for assessing the moderating effects.

4.2.3. Determining the Strength of the Moderating Effects

The power of moderating effects can be evaluated by matching the R2 value of the main and R2 full model [77], and the strength of moderating effects can be assessed by employing the formula given below [70]:

The values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively, represent as weak, moderate and robust moderating effects sizes [70]. As per the rule of [70], the power of the moderating effect of leadership was assessed and is reported in Table 6.

[78], stated that a small effect size does not necessarily mean that the causal moderating effect is irrelevant. “Even a small interaction effect can be meaningful under extreme moderating conditions; if the resulting beta changes are meaningful, then it is important to take these conditions into account” [78]. This recommended that the moderating role of government regulations for the entrepreneurship in the relationship between a business start-up and entrepreneurship development can be significant.

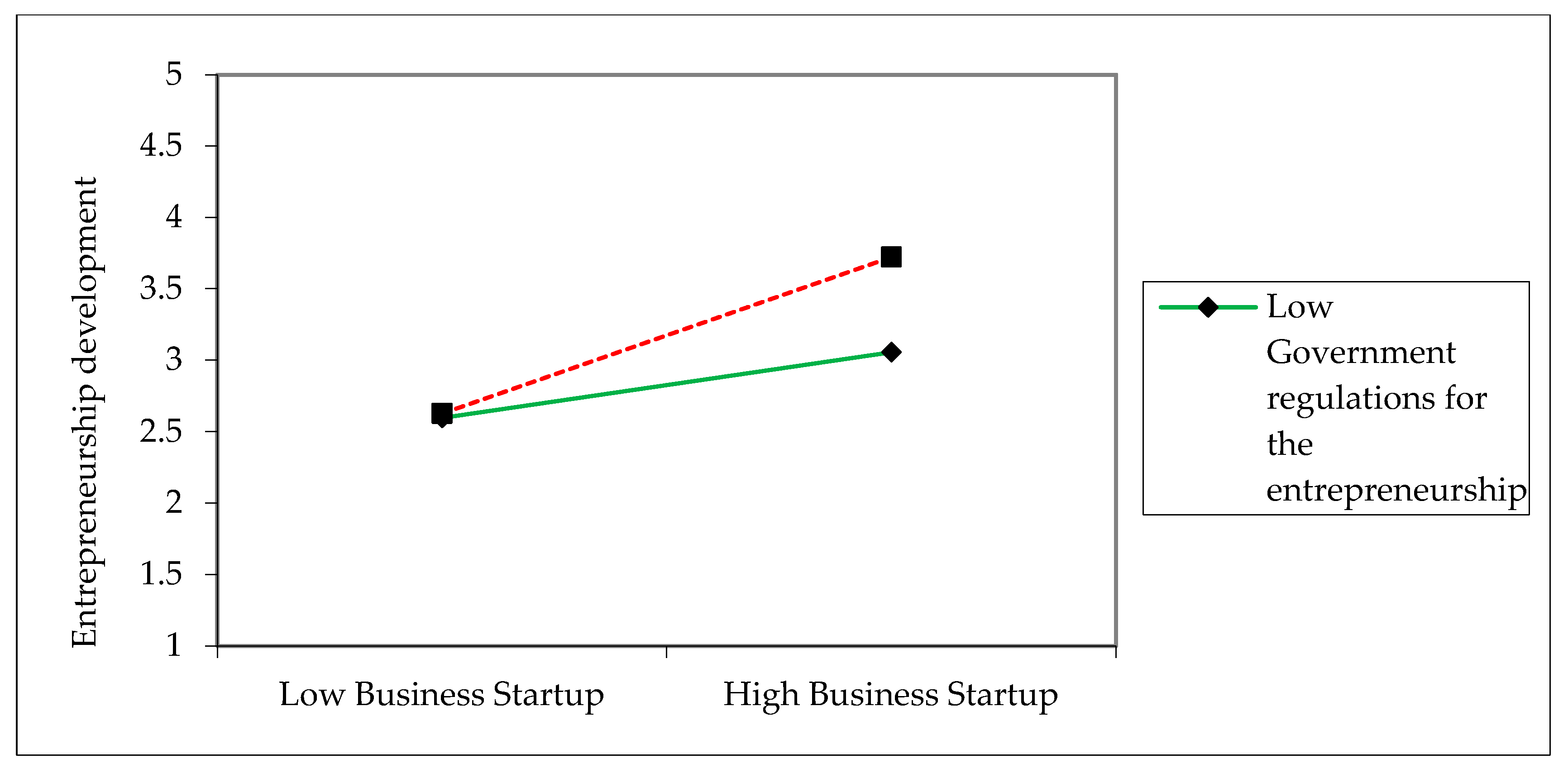

Government regulations for entrepreneurship moderated the slope for the association between business start-up and entrepreneurship development, reflected by the fact that the association became stronger when government regulations for entrepreneurship are high. The slope is given in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The slope for the interactive effect of business start-up and government regulations for entrepreneurship on entrepreneurship development.

5. Discussion

The focus of this paper was to examine the effects of the services provided by business incubators (i.e., network services, capital support, and training programs) on entrepreneurship development. It also examined the mediating and moderating role of business start-up and government regulations in entrepreneurship development. Thus, the results of this study indicate that the reliability and validity of scales measured for networking services 0.878, capital support 0.91, training programs 0.906, business start-up 0.91, government regulations for entrepreneurship 0.728, and entrepreneurship development 0.939. Since this technique is suitable for testing multiple levels of a theoretical framework, and can simultaneously evaluate several relationships between observed and latent variables [79,80]. The suggested path coefficients of the model provide empirical support for all nine hypotheses used in this study. These hypotheses were found positive and significant with t-value > 2 and p-value < 0.05 [17,54,81,82].

The results of this study illustrate that networking services have a positive effect on entrepreneurship development. The results related to hypothesis involve coefficient beta 0.237, standard error 0.04, t-value 6.043 > 2, and p-value 0.000 < 0.05, supported by the previous study [34]. Mahmood, Jamil and Yasir [17] found similar results in which involvement in networking activities is an essential role for business incubators because it links entrepreneurs in and out of business incubation with key investors in the community. These learning opportunities are important because communities with a wider network of peers tend to enjoy higher levels of entrepreneurship and economic growth. These results are in agreement with Khan, Arafat, Raushan, Saleem, Khan, Khan and Entrepreneurship [34], who found that networking services can help entrepreneurs attract more customers, knowledge and ultimately achieve business growth and increase profits.

The results of the present study indicate that capital support has a positive effect on entrepreneurship development. The results include the beta coefficient 0.085, standard error 0.04, t-value 2.18 > 2, and p-value 0.030 < 0.05. Hence, the hypothesis is supported. The same findings were found in the previous study [51,83], in which he reported that after World War II, venture capital became a source of financing in the United States and was subsequently used around the world. He further added that new and untried ideas are highly uncertain, making it impossible to use funds from traditional financial sources, such as debt and equity. In line with the previous study [33], access to capital plays a key role in supporting business and entrepreneurship development, in both direct and indirect ways.

Results from the statistical analysis of this study present that training programs have a positive effect on entrepreneurship development. The significant results were found with positive coefficient value 0.149, standard error 0.05, t-value 2.972 > 2 and p-value 0.003 < 0.05. Meanwhile, the hypothesis was supported based on a significant level. These results are in line with a previous study [14]. These findings indicate that training programs can play an important role in taking advantage of new business opportunities and inspiring potential candidates to set new business plans or to help improve the capabilities of existing entrepreneurs or solve specific business problems.

The results of the present study specify that business start-up has a positive effect on entrepreneurship development. The significant results were found with positive coefficient value 0.389, standard error 0.06, t-value 6.817 > 2 and p-value 0.000 < 0.05. Correspondingly, these results are in line with past studies [84,85]. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South Africa (2012) states that one-third of the country’s economic growth momentum can be attributed to the dynamics of business start-up. They also contribute to promoting research and innovation systems and bring proactive values into society. Rafiq [86] states that a business start-up has multiple impacts on the economy, such as turning an idea into something practical, realizing product market adaptability, and creating long-term value for the company. Alibaba, a start-up in the past, triggered the development of S small and medium enterprises in China, and a large number of Google employees have more than USD 5 million in value. The start-up Finja popularized the use of mobile wallets by injecting USD 1 million from Bridge Round. Karlo Compare provides services for consumers of personal finance products. Karlo compares the USD 20,000 angel capital raised. Repair Desk operates a mobile repair shop and provides related available inventory. This operating software maximizes productivity. It started with USD 40,000 in seed funding. Zameen is the well-funded start-up in Pakistan, with venture capital of USD 31.1 million. Zameen has become Pakistan’s largest real estate market.

Our results also illustrate that government regulations for entrepreneurship have a positive effect on entrepreneurship development and found a positive beta coefficient of 0.174 standard error 0.05, t-value 3.6 > 2, and p-value 0.000 < 0.05. Thus, this hypothesis was supported by the previous study [87]. Pereira and Maia [88] argued that government policy is any course of action aimed at regulating and improving the situation of small and medium-sized enterprises, i.e., conditions for government support, implementation, and funding policies. According to this definition, government policies on entrepreneurship practices are designed to encourage entrepreneurship by creating an enabling environment for entrepreneurs.

Our results also indicate that business start-up positively mediated the relationship among networking services, (positive value of beta coefficient 0.084, standard error 0.02, t-value 4.536 > 2, and p-value 0.000 < 0.05), capital support (positive value of beta coefficient 0.036, standard error 0.02, t-value 2.365 > 2, and p-value 0.018 < 0.05), training programs (positive value of beta coefficient 0.246, standard error 0.04, t-value 6.199 > 2, and p-value 0.000 < 0.05) and entrepreneurship development. The mediating role of the start-up was also found by the previous study [52]. It was concluded that after a period of recession, entrepreneurial activity has begun to pick up and take root in various regions of the world, but incubation services remain a challenge for young, high-growth potential companies in most states. According to Martínez, et al. [89], the business incubators provide a real platform for young entrepreneurs, from where they start their journey to create new businesses, and further, it contributes to the survival of firms and entrepreneurship development.

The findings of this study indicate that government regulations for entrepreneurship moderate the relationship between a business start-up and entrepreneurship development with the positive beta coefficient 0.159, standard error 0.03, t-value 5.292 > 2, and p-value 0.000 < 0.05. These results are supported by Shu, et al. [90], Peng and Liu [91,92]. Findings from the literature argue that legislators had better discontinue subsidies to build generic start-ups, reacting to companies with growth potential. This argument relates to how these regulations guide people in starting limited companies that may be unsuccessful or have minor economic impacts, as well as small-scale employment. Previous studies suggest that the government policies related to entrepreneurial practices aim to encourage entrepreneurship development by creating an enabling environment for entrepreneurs. Thus, government continues to promote the establishment of most of the support programs, sponsorship, and management; especially in developing countries, the government’s proclamation on entrepreneurship will go a long step towards sustainability and positivity. [24,90,93].

6. Conclusions

This study expands the existing knowledge by exploring the importance of business incubators, business start-up, and government regulations to promote entrepreneurship. This study aims to develop a concept to examine the role of business incubators in providing grater services (networking services, capital support, and training programs) to support entrepreneurship development. Secondly, it also examines the mediating and moderating role of business start-up and government regulations for entrepreneurship. Thus, the results of the present study specify that promoting entrepreneurship development is essential to improving a weak economy, and to improve entrepreneurship development. Government regulations and services of business incubators including training programs, capital support, and networking services play a crucial role in supporting entrepreneurship development.

Given the fact that there are many challenges facing entrepreneurs, including a lack of technical and educational skills, inadequate infrastructure and facilities, and support systems, it is hardly surprising that most small businesses do not survive more than a few years. In this situation, business incubators can play an essential role in ensuring the growth and development of small businesses. Several studies conducted throughout the world clearly show the critical role played by business incubators in economic growth and entrepreneurship development. The government of Pakistan has taken several initiatives to support entrepreneurs by establishing institutions such as the National Incubation Centre and the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority-SMEDA for Entrepreneurship, which does a great job in incubating and handling start-ups. However, much needs to be done to develop a sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystem. Private organizations must advance and actively act as incubators for start-ups. There is also an urgent need for public–private initiatives in this sector.

Our findings suggest that the government must look at setting a single window to manage business incubators throughout the country and to coordinate the activities of all institutions and companies that are in the process of incubating new business. Also, there is a need to establish an industry incubator to improve manufacturing because most start-ups now have a service-based business model. Industries like tourism, dry fruit processing, dairy and poultry farming, and fisheries provide excellent opportunities for small entrepreneurs in the country, and there must be an incubator who specializes in these areas.

The present study suggests that in order to promote an entrepreneurial culture, governments in developed and developing countries should focus on business incubation and government regulations for entrepreneurship because, without government regulations, business incubators alone are not enough to understand the entire entrepreneurship ecosystem.

7. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This research provides some contributions to the literature in the field of entrepreneurship. First, it improves understanding of the role or importance of business incubators, government regulations to entrepreneurship development, and the importance of government regulations to business start-up. Thus, government and non-governmental institutions that apply the recommended approach derived from the results of this study will also contribute to training entrepreneurs better to reduce the level of failure. The legislators/policymakers will be supported and guided on what needs to be highlighted in the policy to improve the quality and sustainability of entrepreneurship. It also helps future researchers in a similar field by expounding areas of interest, which will need further study and more in-depth analysis. The study can help fresh graduates and give them the opportunity for new directions for doing business and clarify the importance of specialized training in fostering entrepreneurship. Another contribution of this paper is the conceptual exploration of the vital essential elements for entrepreneurship development. Again, this helps to bring the fragmented literature on business incubators and entrepreneurship development into the broader perspective of the entrepreneurial process. It also serves as a rough roadmap for future theoretical building and testing, inviting more vigorous and complete testing of determinants of entrepreneurship development performance. This paper also helps the government to take an exclusive set-up for extending grants to the individuals and companies who research a new idea or test or develop a novel product or service. The findings of this study help the federal government to take a necessary step to establish new commercial companies with key functions to draw external investors to lend a helping hand the local venture capital market with tax aids. Finally, our study has practical relevance in two ways. First, the findings could aid public policy makers to identify institutional support and programs that best foster entrepreneurial growth and internationalization. Second, it furthers strengthening institutional structures and providing regulatory support to entrepreneurs.

8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study was limited to the country of Pakistan. Although the questionnaires were distributed throughout the country, responses have been received from major cities. Due to time and financial constraints, only the field survey was used as a data collecting tool. It can be spread via social media, emails, or other useful methods.

This study is more suitable for other developed and under-developing countries. This study needs to be more comprehensive by using social capital as a moderator on both sides of the conceptual model used in the study. Future research is recommended to further refine the theoretical bases of each of the variables and to improve the measurement of specific elements and factors in order to clarify the conceptual model for better empirical examining.

Author Contributions

The first author’s contribution share is 50%, and the remaining authors’ contributions are equal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is financed by: [1] Self -organized cluster entrepreneurship behavior reform, evolution, and promotion strategies study (No.16BGL028), China National Social Science Foundation; [2] Study on Bottleneck and Innovation of Post-industrial Intellectual capital development in Jiangsu Province (No. 14JD009), Jiangsu Province Social Science Foundation Project; [3] Perception of fairness in self-organized mass Entrepreneurship (No. 4061160023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this work.

Appendix A

Questionnaire

We are Ph.D. scholars conducting research on An Opportunity Structure for Entrepreneurship Development: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Business Start-up and Government Regulations for Entrepreneurship Development. In this regard, your valuable comments and views are important to gather information for this research. Please spare a few minutes of your precious time and help us to fill this survey.

Please mark √ your choice in the given boxes (please choose only one option in each question).

Demographics:

Province: Sindh Sindh  Punjab Punjab Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Baluchistan Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Baluchistan | Age:  21–30 21–30  31–40 31–40  41–50 41–50  51–60 51–60 |

Gender:  Male Male  Female Female | Education:  Bachelors Bachelors  Masters Masters PhD PhD |

Experience:  1–5 1–5  6–10 6–10 11–15 11–15  16–20 16–20 | Managerial Level:  Top Management Top Management middle management middle management  Lower Management Lower Management |

PART-1: Entrepreneurship Development.

5-point rating scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree. 3= neutral, 4= agree, 5= strongly agree).

| S.N | Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | Business incubators provide a wonderful professional environment that boosts the motivation and productivity of entrepreneurs. | |||||

| 2 | Business incubators provide an opportunity to create innovative business ideas | |||||

| 3 | Business incubators help in enhancing a professional goal to become an entrepreneur | |||||

| 4 | Business incubators help in providing quality of entrepreneurs. | |||||

| 5 | Business incubators help entrepreneurs for survival and entrepreneurship development |

PART-2: Role of Capital Networking Services in Entrepreneurship Development.

5-point rating scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree. 3= neutral, 4= agree, 5= strongly agree).

| S.N | Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | Business incubators provide the latest information on exhibition regulations and specific sectors | |||||

| 2 | Business incubators help in networking with the business community, chambers, and associations | |||||

| 3 | Business incubators provide the latest information on technological updates | |||||

| 4 | Networking service give opportunities to the entrepreneurs to meet with the different parties that involved in the entrepreneurship ecosystem | |||||

| 5 | To work at a commonplace with similar professionals help to solve the common problems, and to share each other’s networks and resources |

PART-3: Role of Capital Support in Entrepreneurship Development.

5-point rating scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree. 3= neutral, 4= agree, 5= strongly agree).

| S.N | Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | Insufficient cheap and long-term capital is a major factor affecting the emergence and development of entrepreneurship in Pakistan | |||||

| 2 | Venture capital is not easily available to SMEs in Pakistan due ignorance | |||||

| 3 | Availability of capital support leads to the existence of new indigenous entrepreneurship in Pakistan | |||||

| 4 | Government has made enough effort to ensure that funds are available for entrepreneurial activities in Pakistan | |||||

| 5 | Unemployment and poverty in Pakistan are due to inadequate entrepreneurship emergence and development. |

PART-4: Role of Training Programs Innovative ideas without setting up capital to convert them into project reality die without implementation.

5-point rating scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree. 3= neutral, 4= agree, 5= strongly agree).

| S.N | Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | Business incubators help in improving the capacity building skills | |||||

| 2 | Business incubators help in improving product development skills | |||||

| 3 | Business incubators help in improving business management skills | |||||

| 4 | Business incubators help in improving marketing skills | |||||

| 5 | Business incubators help in providing customized training skills |

PART-5: Business Start-up.

5-point rating scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree. 3= neutral, 4= agree, 5= strongly agree).

| S.N | Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | Business incubators provide mentoring and coaching sessions to help the incubates to get quickly and follow the right track to start a new business | |||||

| 2 | Overall, the business incubator is a good platform to start a new business by entrepreneurs/individuals and to promote entrepreneurship | |||||

| 3 | Business incubators support the development of start-ups by providing advisory and administrative support services | |||||

| 4 | Business incubators provide networking services has a positive impact on the opportunity to business start-up | |||||

| 5 | A business start-up is the finest tool to build a mediating relation between business incubation and entrepreneurship development |

PART-6: Government Regulations for Entrepreneurship.

5-point rating scale (1= strongly disagree, 2= disagree. 3= neutral, 4= agree, 5= strongly agree).

| S.N | Statements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | The exchange rate policy in Pakistan supports the competitiveness of enterprises | |||||

| 2 | The state of diplomatic relations of your country with neighboring countries facilitates business activity | |||||

| 3 | The lack of legal protection is not an important obstacle to starting a new business | |||||

| 4 | The police effectively safeguard personnel security so that it is not an important consideration in business activity | |||||

| 5 | Unemployment legislation provides an incentive to look for work |

THANK YOU

References

- National Institute of Population Studies-NIPS/Pakistan; ICF. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18; NIPS/Pakistan and ICF: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, A.; Zaman, K.; Khan, M.; Ahmad, M.J.J.A.S. Measuring unemployment costs on socio economic life of urban Pakistan. J. Am. Sci. 2012, 8, 703–714. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics, P.B.O. Pakistan Employment Trends 2018; Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Statistics Division M/o Statistics Government of Pakistan Islamabad: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2018.

- Shah, S.A.A. Determinants of Public-Private-Partnership Performance: The Case of Pakistan. Ph.D. Thesis, James Cook University, Douglas, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ShuHong, Y.; Zia-ud-Din, M.J.L.; Issues, L. Questioni di diritto del lavoro in Pakistan: Il fondamento storico della legislazione lavoristica e delle associazioni sindacali. Labour Law Issues 2017, 3, 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Pakistan, Finance Division. Economic Survey of Pakistan, 2009-10; Government of Pakistan, Finance Division: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2010.

- Eroglu, O.; Piçak, M. Entrepreneurship, national culture and Turkey. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y. The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, D.J. Entrepreneurship and New Firm: Theory and Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akinbola, O.A.; Ogunnaike, O.O.; Amaihian, A.B. The influence of contextual factors on entrepreneurial intention of university students in Nigeria. Creat. Glob. Compet. Econ. 2020, 1–3, 2297–2309. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Sung, S. The Effect of Entrepreneurship on Start-Up Open Innovation: Innovative Behavior of University Students. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudana, I.M.; Apriyani, D.; Supraptono, E.; Kamis, A. Business incubator training management model to increase graduate competency. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, B.; Singh, M. Business incubation to support entrepreneurship education in Amhara National Regional State Public Universities. ZENITH Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Res. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zreen, A.; Farrukh, M.; Nazar, N.; Khalid, R. The Role of Internship and Business Incubation Programs in Forming Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Empirical Analysis from Pakistan. J. Manag. Bus. Adm. Cent. Eur. 2019, 27, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalkaka, R. Technology Business Incubation: a Toolkit on Innovation in Engineering, Science and Technology; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Waqas, M.; Rehman, M.; Rehman, A. The Barriers and Challenges Faced by Private Sector Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in Promoting Sustainable Development: A Qualitative Inquiry in Pakistan. Pak. J. Educ. 2019, 36, 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, N.; Jamil, F.; Yasir, N. Role of business incubators in entrepreneurship development in Pakistan. City Univ. Res. J. 2016, 37–44. Available online: http://www.cusit.edu.pk/curj/Journals/Journal/special_aic_16/5.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Mahmood, N.; Jianfeng, C.; Munir, H.; Yasir, N. Impact of Factors that Inhibit the Drive of Entrepreneurship in Pakistan: Empirical Evidence from Young Entrepreneurs and Students. Int. J. U-E-Serv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, D. National Business Incubation Association 10th Anniversary Survey of Business Incubators, 1985-1995: A Decade of Success; National Business Incubation Association: Athens, OH, USA, 1996; Available online: https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=o2bhsoNRKU8C&pg=PA149&lpg=PA149&dq=D+Adkins+-+1996+-+%E2%80%A6+Business+Incubation+Association&source=bl&ots=5IxfSWy8yh&sig=ACfU3U3-5m2WW7uGj7Xk6Hv6Yu-a-BHO1A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiDyZXI_e_nAhXVD2MBHRy1D2gQ6AEwAXoECAwQAQ#v=onepage&q=D%20Adkins%20-%201996%20-%20%E2%80%A6%20Business%20Incubation%20Association&f=false (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Campbell, C. Change Agents In The New Economy: Business Incubators And E. Econ. Dev. Rev. 1989, 7, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Wolniak, R.; Grebski, M.E.; Skotnicka-Zasadzień, B. Comparative Analysis of the Level of Satisfaction with the Services Received at the Business Incubators (Hazleton, PA, USA and Gliwice, Poland). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshun, J.P. Business incubation as strategy. Bus. Strategy Ser. 2009, 3, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapisz, A. Do government and legal barriers impede entrepreneurship in the US? An exploratory study of perceived vs. actual barriers. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, M.; Hamdan, A. The moderating role of governmental support in the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth: A study on the GCC countries. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 11, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Gantes, V.M.; Sorensen, R.P.; Nieri, A.H. Fostering Entrepreneurship through Business Incubation: The Role and Prospects of Postsecondary Vocational-Technical Education; National Center for Research in Vocational Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED399396 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Pearce, J.; Grafman, L.; Colledge, T.; Legg, R. Leveraging Information Technology, Social Entrepreneurship, and Global Collaboration for just Sustainable Development; Hyper Articles en Ligne (HAL): Lyon, France, 2019; Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02120513/document (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Abbas, J.; Raza, S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Minai, M.S.; Bano, S. The Impact of Entrepreneurial Business Networks on Firms’ Performance Through a Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mort, G.S.; Weerawardena, J. Networking capability and international entrepreneurship: How networks function in Australian born global firms. Int. Mark. Rev. 2006, 23, 549–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkkeli, L.; Kuivalainen, O.; Saarenketo, S.; Puumalainen, K. Institutional environment and network competence in successful SME internationalisation. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeil, A. Venture Capital: New Ways of Financing Technology Innovation; Human Development Report Office (HDRO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 2001.

- Mittelstädt, A.; Cerri, F. Fostering entrepreneurship for innovation. OECD Sci. Technol. Ind. Work. Papers 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.; Capizzi, V. The role of venture capital in the emerging entrepreneurial finance ecosystem: Future threats and opportunities. Ventur. Cap. 2019, 21, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, V.; Desai, S.; Baird, R. Access to Capital for Entrepreneurs: Removing Barriers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.M.; Arafat, M.Y.; Raushan, M.A.; Saleem, I.; Khan, N.A.; Khan, M. Does intellectual capital affect the venture creation decision in India? J. Innov. Entrep. 2019, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, F.; Ismail, K.; Mahmood, N. University Incubators: A gateway to an entrepreneurial society. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 6, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Alpenidze, O.; Sanyal, S. Key success factors for business incubators in Europe: An empirical study. Acad. Entrep. J. 2019, 25, 9–10. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/business-incubators-in-europe-an-empirical-study-7964.html (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Yusubova, A.; Andries, P.; Clarysse, B. The role of incubators in overcoming technology ventures’ resource gaps at different development stages. RD Manag. 2019, 49, 803–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.M.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Parallel play: Startups, nascent markets, and effective business-model design. Adm. Sci. Q. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Saleem, I.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Khan, A. Determinants of agricultural entrepreneurship: A GEM data based study. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, D.; Reimer, T. Startup founders and their LinkedIn connections: Are well-connected entrepreneurs more successful? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stel, A.; Storey, D.J.; Thurik, A.R. The effect of business regulations on nascent and young business entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 28, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallbone, D.; Welter, F. Entrepreneurship and government policy in former Soviet republics: Belarus and Estonia compared. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, S.C.; Pearce, J.A. The need for innovation as a rationale for government involvement in entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2009, 21, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetshin, R.; Shafigullina, A. Government regulation of small and medium entrepreneurship under the influence of value-time benchmarks. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Etikan, I.; Bala, K. Sampling and sampling methods. Biom. Biostat. Int. J. 2017, 5, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, O. Process tracing and elite interviewing: A case for non-probability sampling. PS Political Sci. Politics 2007, 40, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Covin, J.G. Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramar, R.; Muthukumaran, C.K. Role of business incubation centers in promoting entrepreneurship in Tamilnadu. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Ur Rehman, H.; Asim, S. Induction of business incubation centers in educational institutions: An effective approach to foster entrepreneurship. J. Entrep. Educ. 2019, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Okpala, K.E. Venture capital and the emergence and development of entrepreneurship: A focus on employment generation and poverty alleviation in Lagos State. Int. Bus. Manag. 2012, 5, 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- El Shoubaki, A.; Laguir, I.; den Besten, M. Human capital and SME growth: The mediating role of reasons to start a business. Small Bus. Econ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, F.L. Quantitative notes on the extent of governmental regulations in various OECD nations. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2002, 20, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozali, L.; Masrom, M.; Zagloel, T.Y.M.; Haron, H.N.; Dahlan, D.; Daywin, F.J.; Saryatmo, M.A.; Saraswati, D.; Fitri, A.; Syamas, E.H.S. Critical Success And Moderating Factors Effect In Indonesian Public Universities’business Incubators. Int. J. Technol. 2018, 9, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.; Yuan, L.; Iqbal, S.; Hussain, R.; Ali, S. Impact of Price on Customer Satisfaction; mediating role of Consumer Buying Behaviour in Telecom Sector. Int. J. Res. 2019, 6, 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares: The better approach to structural equation modeling? Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P. Path analysis with composite variables. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1996, 31, 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate data analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Global Edition; Pearson Higher Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Pieper, T.M.; Ringle, C.M. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: A review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, P.R. Statistics Explained; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, XXI; L Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D. A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in MIS Quarterly. Inf. Syst. Q. 2012, 36, 10. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2176426 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Geisser, S. A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Schumacker, R.E.; Wothke, W. A comparative review of interaction and nonlinear modeling. In Interaction Nonlinear Effects in Structural Equation Modeling; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Fassott, G. Testing moderating effects in PLS path models: An illustration of available procedures. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 713–735. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliem, J.A.; Gliem, R.R. Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for Likert-type scales. In Proceedings of the Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, Columbus, OH, USA, 8–10 October 2003; Available online: http://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/344 (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Njau, J.M.; Mwenda, L.M.K.; Wachira, A.W. Effect Of Infrastructural Facilities Support Provided By Business Incubators On Technology Based New Venture Creation In Kenya. Int. J. Entrep. Proj. Manag. 2019, 4, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Redondo, M.; Camarero, C. Social Capital in University Business Incubators: Dimensions, antecedents and outcomes. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, V.; Uddin, M. Role of Venture Capital in Spurring Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2009, 5, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saripah, I.; Abduhak, I.; Heryanto, N.; Lestari, R.D.; Putra, A. Study On Evaluation Of Startup Business Training Models In The Entrepreneurship Skills Education Program At West Java Course And Training Institute, Indonesia. Int. E-J. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, A.; Ghezzi, A.; Dell’Era, C.; Pellizzoni, E. Fostering digital entrepreneurship from startup to scaleup: The role of venture capital funds and angel groups. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 145, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M. Significance of Financing Start-Up Entrepreneurs in Pakistan; Daily Times: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hechavarría, D.M.; Ingram, A.E. Entrepreneurial ecosystem conditions and gendered national-level entrepreneurial activity: A 14-year panel study of GEM. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Maia, R. The role of politics and institutional environment on entrepreneurship: Empirical evidence from Mozambique. J. Int. Relat. 2019, 10, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, K.R.G.; Fernández-Laviada, A.; Crespo, Á.H. Influence of business incubators performance on entrepreneurial intentions and its antecedents during the pre-incubation stage. Entrep. Res. J. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; De Clercq, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C. Government institutional support, entrepreneurial orientation, strategic renewal, and firm performance in transitional China. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Liu, Y. How government subsidies promote the growth of entrepreneurial companies in clean energy industry: An empirical study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asim, S.; Li, C.; Makhdoom, H.U.R.; Zafar, Z. Entrepreneurial Technology Opportunism and Its Impact on Business Sustainability with the Moderation of Government Regulations. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 7, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.D.; Kim, N.; Buisson, B.; Phillips, F. A cross-national study of knowledge, government intervention, and innovative nascent entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 84, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).