Applying the Theory of Access to Food Security among Smallholder Family Farmers around North-West Mount Kenya

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Access to Productive Resources and Food Security

1.2. Theory of Access, Bundles of Rights and Powers, and the Link to Food Security

2. Materials and Methods

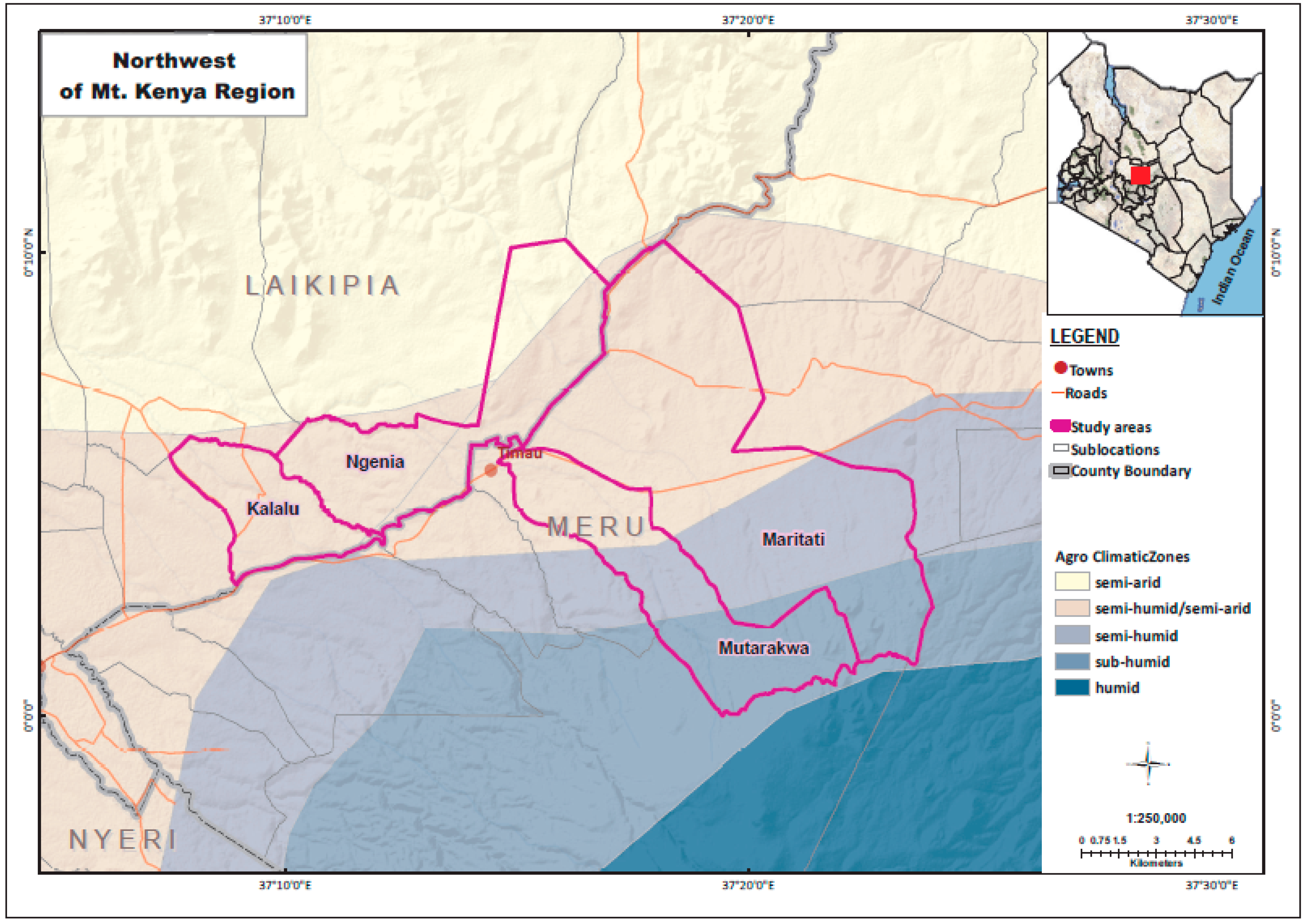

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Characteristics of Studied Population

3. Results

3.1. Access Mechanisms by Food Secure and Insecure Households

3.2. Correlation Between Household Food Security and the Bundle of Rights and Powers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

References

- African Smallholder Farmers Group. Supporting Smallholder Farmers in Africa: A Framework for an Enabling Environment; African Smallholder Farmers Group: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Food Security Information Network. Global Report on Food Crisis 2018. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000069227/download/?_ga=2.244174085.1862504590.1582542458-1500710275.1566571088 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Samberg, L.H.; Gerber, J.S.; Ramankutty, N.; Herrero, M.; West, P.C. Subnational Distribution of Average Farm Size and Smallholder Contributions to Global Food Production. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Mehrabi, Z.; Jarvis, L.; Chookolingo, B. How Much of the World’s Food Do Smallholders Produce? Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeub, B.E.; Chappell, M.J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R.B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The State of Family Farms in the World. World Dev. 2016, 87, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Gĩthĩnji, M.W. Small Farms, Smaller Plots: Land Size, Fragmentation, and Productivity in Ethiopia. J. Peasant Stud. 2018, 45, 757–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakawuka, P.; Simon, L.; Petra, S.; Jennie, B. A Review of Trends, Constraints and Opportunities of Smallholder Irrigation in East Africa. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, J.Y.T.; Gordon, M.H. Local Institutions and Smallholder Women’s Access to Land Resources in Semi-Arid Kenya. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 252–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Xia, F. Smallholders’ Land Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: A New Landscape? Food Policy 2017, 67, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, T.S.; Muyanga, M. Land Constraints in Kenya’s Densely Populated Rural Areas: Implications for Food Policy and Institutional Reform. Food Sec. 2012, 4, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maxwell, D.; Wiebe, K. Land Tenure and Food Security. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenaw, S.; Islam, K.M.Z.; Parviainen, T. Effects of Land Tenure and Property Rights on Agricultural Productivity in Ethiopia, Namibia and Bangladesh; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bugri, J.T.; Yeboah, E. Understanding Changing Land Access and Use by the Rural Poor in Ghana; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba, G.I. Land Property Rights and Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from Panama. In Responsible Land Governance: Towards an Evidence Based Approach. Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty; Center for Data Science and Service Research: Sendai, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, J.C.; Peluso, N.L. A Theory of Access. Rural Sociol. 2003, 68, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, L.; Rist, S. Seeing Land Deals through the Lens of the ‘Land–Water Nexus’: The Case of Biofuel Production in Piura, Peru. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasselle, A.-S.; Gaspart, F.; Platteau, J.-P. Land Tenure Security and Investment Incentives: Puzzling Evidence from Burkina Faso. J. Dev. Econ. 2002, 67, 373–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, B.; Colque, G. Bolivia’s Soy Complex: The Development of ‘Productive Exclusion’. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 43, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.L. Progress in Physical Geography Power, Knowledge and Political Ecology in the Third World: A Review. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1998, 1, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liniger, H.; Studer, R.M.; Hauert, C.; Gurtner, M. Sustainable Land Management in Practice Guidelines and Best Practices for Sub-Saharan Africa; TerrAfrica, World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2011. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i1861e/i1861e00.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Zaehringer, J.G.; Wambugu, G.; Kiteme, B.; Eckert, S. How Do Large-Scale Agricultural Investments Affect Land Use and the Environment on the Western Slopes of Mount Kenya? Empirical Evidence Based on Small-Scale Farmers’ Perceptions and Remote Sensing. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 213, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejika Speranza, C. Buffer Capacity: Capturing a Dimension of Resilience to Climate Change in African Smallholder Agriculture. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiteme, B.P.; Gikonyo, J. Preventing and Resolving Water Use Conflicts in the Mount Kenya Highland–Lowland System through Water Users’ Associations. Mt. Res. Dev. 2002, 22, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, S.; Kiteme, B.; Njuguna, E.; Zaehringer, J.G. Agricultural Expansion and Intensification in the Foothills of Mount Kenya: A Landscape Perspective. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, A.; Ifejika Speranza, C.; Roden, P.; Kiteme, B.; Wiesmann, U.; Nüsser, M. Small-Scale Farming in Semi-Arid Areas: Livelihood Dynamics between 1997 and 2010 in Laikipia, Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutea, E.; Bottazzi, P.; Jacobi, J.; Kiteme, B.; Speranza, C.I.; Rist, S. Livelihoods and Food Security Among Rural Households in the North-Western Mount Kenya Region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Kenya. National Land Use Policy; Government of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017.

- Muraoka, R.; Jin, S.; Jayne, T.S. Land Access, Land Rental and Food Security: Evidence from Kenya. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Kenya. The Water Act; Government of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016.

- Ifejika Speranza, C.; Kiteme, B.; Wiesmann, U.; Jörin, J. Community-Based Water Development Projects, Their Effectiveness, and Options for Improvement: Lessons from Laikipia, Kenya. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2018, 37, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizimana, J.-C.; Richardson, J.W. Agricultural Technology Assessment for Smallholder Farms: An Analysis Using a Farm Simulation Model (FARMSIM). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejika Speranza, C.; Kiteme, B.; Wiesmann, U. Droughts and Famines: The Underlying Factors and the Causal Links among Agro-Pastoral Households in Semi-Arid Makueni District, Kenya. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduol, J.B.A.; Kyushu, U.; Hotta, K.; Shinkai, S.; Tsuji, M. Farm Size and Productive Efficiency: Lessons from Smallholder Farms in Embu District, Kenya. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 2006, 51, 449–58. [Google Scholar]

- Okech, S.H.O.; Gaidashova, S.V.; Gold, C.S.; Nyagahungu, I.; Musumbu, J.T. The Influence of Socio-Economic and Marketing Factors on Banana Production in Rwanda: Results from a Participatory Rural Appraisal. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2005, 12, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, J.R.; Kohler, H.-P.; Watkins, S.C. Social Networks and Changes in Contraceptive Use over Time: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study in Rural Kenya. Demography 2002, 39, 713–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A. The Power of Reciprocity: Fairness, Reciprocity, and Stakes in Variants of the Dictator Game. J. Confl. Resolut. 2004, 48, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiba, M.; Collinson, M.; Hunter, L.; Twine, W. Social Capital Is Subordinate to Natural Capital in Buffering Rural Livelihoods from Negative Shocks: Insights from Rural South Africa. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, S.S.; Catacutan, D.; Ajayi, O.C.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nieuwenhuis, M. The Role of Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions in the Uptake of Agricultural and Agroforestry Innovations among Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2015, 13, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeni, L.; Moeletsi, M.; Thavhana, M.; Randela, M.; Mokoena, L. Barriers Affecting Sustainable Agricultural Productivity of Smallholder Farmers in the Eastern Free State of South Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide; FHI 360/FANTA Version 2; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Food programme. Food Consumption Score Nutritional Quality Analysis Guidelines (FCS-N); United Nations World Food Programme, Food Security Analysis (VAM): Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D.; Caldwell, R. The Coping Strategies Index. In A Tool for Rapid Measurement of Household Food Security and the Impact of Food Aid Programs in Humanitarian Emergencies, 2nd ed.; Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc. (CARE): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide; FHI 360/FANTA Version 3; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bilinsky, P.; Swindale, A. Months of Adequate Household Food Provisioning (MAHFP) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide; FHI 360/FANTA Version 4; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2000, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Göb, R.; McCollin, C.; Ramalhoto, M.F. Ordinal Methodology in the Analysis of Likert Scales. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 2nd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kiriti-Nganga, T.; Mugo, M.; Bonanomi, E.B.; Kiteme, B. Impact of Economic Regimes on Food Systems in Kenya; Discussion Paper; Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, A. Equipment and Tools for Small-Scale Intensive Crop Production. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Landscape and Urban Planning. Natl. Cent. Appropr. Technol. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitonga, S.; Mukoya, W.S.M. An Evaluation of the Influence of Information Sources on Adoption of Agroforestry Practices in Kajiado Central Sub-County, Kenya. Univers. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 4, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwololo, H.M.; Nzuma, J.M.; Ritho, C.N.; Aseta, A. Is the Type of Agricultural Extension Services a Determinant of Farm Diversity? Evidence from Kenya. Dev. Stud. Res. 2019, 6, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis-Hansen, E. Concepts and Experiences with Demand Driven Advisory Services: Review of Recent Literature with Examples from Tanzania; DIIS Working Paper No. 2004/7; Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Okoba, B.O.; Graaff, J.D. Farmers’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Soil Erosion and Conservation Measures in the Central Highlands, Kenya. Land Degrad. Dev. 2005, 16, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hulst, F.J.; Posthumus, H. Understanding (Non-) Adoption of Conservation Agriculture in Kenya Using the Reasoned Action Approach. Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Jayne, T.S. Land Rental Markets in Kenya: Implications for Efficiency, Equity, Household Income, and Poverty. Land Econ. 2013, 89, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.A.; Argote, L.; Levine, J.M. Knowledge Transfer between Groups via Personnel Rotation: Effects of Social Identity and Knowledge Quality. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 96, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczberski, G.; Curry, G.N.; Bue, V.; Germis, E.; Nake, S.; Tilden, G.M. Diffusing Risk and Building Resilience through Innovation: Reciprocal Exchange Relationships, Livelihood Vulnerability and Food Security amongst Smallholder Farmers in Papua New Guinea. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bundle of Rights and Powers | Empirical Research on the Role of These Factors in Enabling Access to Productive Resources |

|---|---|

| Rights-based access | In Kenya, land use and access rights for individuals, corporations, or collective trusts is either through lease or freehold title [27]. Access to land rights can also be obtained via rental agreement, either formal (with a written contract) or informal (with a verbal agreement) [28]. |

| Rights-based access to irrigation water | Every water resource in Kenya is vested in the government, which holds it in trust for its citizens [29]. Thus, access to water rights can only be obtained through an application for a permit to abstract groundwater (borehole) or river water (weir) or by enrolling in a Community Water Project (CWP) [30]. |

| Access to capital | As rural household incomes may fluctuate due to shocks, access to capital in the form of credit is a way of stabilizing access to financial resources [12]. |

| Access to technology | Access to technology such as farm tools help farmers extract the resource they need access to. Productive hand tools are essential to farming, from production to harvesting. Tools and implements critically determine farm activities and facilitate increased agricultural production that can restore food security [31,32]. |

| Access to labour and labour opportunities | In Kenya, small-scale agriculture is labour intensive and farmers rarely use machinery or draught power. Family labour is the main source of labour, often complemented with wage labour and unpaid reciprocal exchange of labour [33]. Maintaining access to labour is vital in managing the peaks of agricultural work in every crop production stage to ensure maximum production yields. One way of maintaining access to labour is by generating capital through off-farm job opportunities. |

| Access to authority | Access to authority places a household at a more advantageous position within the local to regional power structures. For instance, in the study area, some members were able to maintain access to water for irrigation through community water projects without paying the monthly charges due to favours from the project leaders [30]. |

| Access to markets | In general, market access is seen as the ability of individuals to gain, control, or maintain entry into exchange relations. Access to markets is essential to obtain key inputs (e.g., tools, fertilizers, better seeds) and to sell farm produce. Areas close to the market tend to enjoy high farm gate prices of produce and these prices decline with increasing distance to the market [34]. Proximity to the market also makes access convenient and less costly. |

| Access through social identity | Aspects of social identity influence the preferences and needs required to access social networks of organizations and community groupings. Individuals regularly make decisions not in social isolation, but in interaction with others; in turn, social groupings reinforce or alter norms by providing examples of behaviour that others may copy [35]. Such social groupings promote social learning and collaboration by providing new information and facilitate evaluation of the information, thus reducing the uncertainty associated with innovations, such as new farm technologies. |

| Access via social relations | Access via negotiation of other social relations is based on how households give and/or receive help from external sources such as neighbours, friends, or relatives. It is often believed that the more a household gives, the more it possibly receives, in the principle of reciprocity [36]. Reciprocity has the effect of cushioning households from shocks and usually poorer households depend on this social capital [37]. |

| Access to knowledge | The information farmers have form the basis of their perceptions and attitudes towards issues such as technology adoption [38]. New sustainable agricultural practices are more likely to be adopted by households with access to a higher education level [39]. |

| Variable | Indicator | Definition of the Indicator | Ranking Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land rights | Total surface of land used under various formal rights-based access | Total land used that is under title deed, leasehold, allotment letter, and/or written contractual document, either via rental or government programme | 3 = All land used under formal agreement, 2 = Over half of the land under formal agreement, 1 = Less than half of the land under formal agreement, 0 = No formal rights |

| Total surface of land under various informal rights | Total land that is under any verbal agreement, squatting, or theft | 3 = All land used under informal agreement, 2 = Over half of the land under informal agreement, 1 = Less than half of the land under informal agreement, 0 = No informal rights | |

| Water rights | Ability to access water for irrigation | Household ability to access water for irrigation through membership in WRUA, community water projects, borehole, or river intake | 3 = Access to all sources, 2 = Access to two or more sources, 1 = Access to fewer than two sources, 0 = No access to water for irrigation |

| Access to capital | Membership in organizations that facilitate access to credit | Household membership in facilities that enable access to credit. Facilities considered: Banks, Savings and Credit Cooperative Societies (SACCO), Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCA) | 3 = Membership in the three facilities, 2 = Membership in two facilities, 1 = Membership in one facility, 0 = No membership |

| Access to technology | Ownership of different types of tools | Ownership of different types of farm tools: shallow weeder, spade, rake, mattock, sprinkler, hosepipe, machete, knapsack, slasher, hoe, fork jembe, wheelbarrow | 3 = Owns all the selected hand tools, 2 = Owns six and over of the selected hand tools, 1 = Owns fewer than six of the selected hand tools, 0 = No tools |

| Access to labour and labour opportunities | Existence of access to family-external and off-farm labour | Household ability to access labour from outside the farm and access to off-farm labour. Types of labour sources considered: Extra-family labour sourced from reciprocal labour exchange, permanent contracted wage labour, temporal hiring; or off-farm work of family members | 3 = Accesses labour additional to family work force and secured off-farm employment, 2 = Accesses labour additional to family farm work force, but no off-farm employment, 1 = Accesses only off-farm employment, 0 = No labour beyond family labour and no off-farm employment |

| Access to authority | Opportunity to be part of authorities or to interact with authorities for accessing land and water | Socio-political relations that enable access to land and water. Types of relations considered: Local, county and national government, Community water project, Water Resources Associations, farmer groups, women groups, religious groups | 3 = A household being a member of authorities, 2 = Opportunity to benefit through interacting with members of authority, 1 = Opportunity to interact with authorities with no direct benefit, 0 = No opportunity to interact with authorities |

| Access to markets | Distance to the market in kilometres | The distance in km a household has to cover in order to reach the desired market | 3 = <2 kms, 2 = 2–4 kms, 1 = >4 kms, 0 = No market |

| Access via social network/relations | Opportunity to receive help from external sources | A household that receives help from external sources. Type of help considered: Help related to Land, water, farming, market, financial, food | 3 = Receives all types of help, 2 = Receives three and above different types of help, 1 = Receives less than three different types of help, 0 = No help received |

| Access through social identity | Membership in socio-cultural groups meeting or not meeting own expectations | A household that is a member of any socio-cultural group and its perceptions on whether it meets own expectations or not. Types of socio-cultural groups considered: Religious groups, women groups, farmer groups, community groups, working groups | 3 = Membership in more than one socio-cultural group that meets expectations, 2 = Membership in only one socio-cultural group that meets expectations, 1 = Membership in socio-cultural group that does not meet expectations, 0 = A household that is not a member of any social group |

| Access to knowledge | Level of formal education attained among the household members | The levels of formal education among the household members. Types of education considered: University or college education, secondary or post primary vocational training, primary education | 3 = University degree/college, 2 = Secondary education or post primary vocational training, 1 = Primary education, 0 = No education |

| Characteristics of the Overall Sample Size (N = 76) | No. of Households (%) | Characteristics of the Two Subsets (n = 38) | Food Secure (%) | Food Insecure (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food security status | Sample size | 38 (100) | 38 (100) | |

| Food secure | 38 (50) | |||

| Food insecure | 38 (50) | |||

| Respondent gender | Respondent gender | |||

| Female | 48 (63) | Female | 20 (53) | 28 (74) |

| Male | 28 (37) | Male | 18 (47) | 10 (26) |

| Respondent age | Respondent age | |||

| 18–28 | 6 (8) | 18–28 | 2 (5) | 4 (11) |

| 29–39 | 22 (29) | 29–39 | 8 (21) | 14 (37) |

| 40–50 | 22 (29) | 40–50 | 13 (34) | 9 (24) |

| >50 | 26 (34) | >50 | 15 (39) | 11 (29) |

| Factors of Bundle of Rights and Power | Food Secure Households | Food Insecure Households | Fisher’s Exact Test P-Value (Test for Statistically Significant Differences) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal rights-based access to land | Medium to high | Medium to high | 0.073 |

| Informal rights-based access to land | Inexistence to Low | Inexistence to Low | 0.115 |

| Rights-based access to irrigation water | Low to medium | Low to medium | 0.278 |

| Access to capital | Low to medium | Low to medium | 0.867 |

| Access to technology | Medium to high | Low to medium | 0.001* |

| Access to labour and labour opportunities | Low to medium | Inexistence to Low | 0.481 |

| Access to authority | Low to medium | Low to medium | 0.322 |

| Access to markets | Low to medium | Low to medium | 0.494 |

| Access through social identity | Low to medium | Low to medium | 0.954 |

| Access via social relations | Medium to high | Medium to high | 0.311 |

| Access to knowledge | Medium | Medium to high | 0.835 |

| Type of Farm Tools Owned | Number of Food Secure Households | Number of Food Insecure Households | Type of Tools and Implements Owned | Number of Food Secure Households | Number of Food Insecure Households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axe | 5 | 1 | Chaff cutter | 7 | 0 |

| Fork jembe | 38 | 37 | Cold chisel | 1 | 0 |

| Hoe | 36 | 28 | Drip kit | 5 | 0 |

| Hosepipe | 35 | 30 | Hacksaw | 1 | 0 |

| Knapsack sprayer | 37 | 33 | Harrow | 1 | 0 |

| Machete | 38 | 37 | Ox-drawn cart | 1 | 0 |

| Mattock | 17 | 9 | Plough | 2 | 0 |

| Rake | 24 | 8 | Shallow weeder | 1 | 1 |

| Slasher | 34 | 19 | Thresher | 1 | 0 |

| Spade | 36 | 34 | Tractor | 1 | 0 |

| Sprinkler | 31 | 28 | Water pump | 3 | 0 |

| Wheelbarrow | 28 | 24 |

| Mechanism of Access | Household Food Security | Formal Rights-Based Access to Land | Informal Rights-Based Access to Land | Access to Water | Access to Capital | Access to Technology | Access to Labour and Labour Opportunities | Access to Authority | Access to Market | Access to Knowledge | Access through Social Identity | Access via Social Network |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household food security | 1 | |||||||||||

| Formal land rights | 0.40 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Informal land rights | −0.41 | −0.99 * | 1 | |||||||||

| Access to water | 0.41 | 0.42 | −0.43 | 1 | ||||||||

| Access to capital | 0.38 | 0.13 | −0.08 | 0.62 * | 1 | |||||||

| Access to technology | 0.83 * | 0.60 * | −0.59* | 0.69 * | 0.59 * | 1 | ||||||

| Access to labour and labour opportunities | −0.16 | −0.63 * | 0.66* | 0.10 | 0.47 | −0.17 | 1 | |||||

| Access to authority | 0.48 | 0.24 | −0.25 | 0.85 * | 0.60 * | 0.62 * | 0.06 | 1 | ||||

| Access to market | 0.08 | 0.27 | −0.29 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.13 | −0.15 | 0.55 | 1 | |||

| Access to knowledge | 0.12 | 0.28 | −0.24 | 0.66 * | 0.79 * | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 1 | ||

| Access through social identity | 0.22 | −0.34 | 0.36 | −0.47 | 0.84* | 0.33 | 0.69 * | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.64 * | 1 | |

| Access via social relations | −0.47 | −0.43 | 0.43 | −0.43 | −0.34 | −0.57* | −0.0.8 | −0.28 | −0.18 | −0.51 | −0.11 | 1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mutea, E.; Rist, S.; Jacobi, J. Applying the Theory of Access to Food Security among Smallholder Family Farmers around North-West Mount Kenya. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051751

Mutea E, Rist S, Jacobi J. Applying the Theory of Access to Food Security among Smallholder Family Farmers around North-West Mount Kenya. Sustainability. 2020; 12(5):1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051751

Chicago/Turabian StyleMutea, Emily, Stephan Rist, and Johanna Jacobi. 2020. "Applying the Theory of Access to Food Security among Smallholder Family Farmers around North-West Mount Kenya" Sustainability 12, no. 5: 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051751

APA StyleMutea, E., Rist, S., & Jacobi, J. (2020). Applying the Theory of Access to Food Security among Smallholder Family Farmers around North-West Mount Kenya. Sustainability, 12(5), 1751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051751