Abstract

Access to productive resources such as land and water is fundamental for households that rely on crop and livestock production for their livelihoods. Research often assumes that agricultural production—and thus, food security—are favoured by tenure security of resources (as represented by a “bundle of property rights”). However, research has not yet elucidated how food security is influenced by additional factors, represented within a “bundle of powers”. Guided by the Theory of Access developed by Ribot and Peluso, we explore the main factors in the respective bundles of rights and powers that influence household food security around north-west Mount Kenya. We interviewed 76 households—38 food secure and 38 food insecure—who were subsampled from a previous food security survey of 380 households. Results show that household food insecurity was not exclusively the result of a lack of private property rights as many farmers had retained their property rights. Instead, a major factor preventing access to productive resources was the difficulty faced by food insecure households in accessing farm technology (i.e. hand tools and implements). Access to authority and via social relations were significantly correlated with access to technology, so improving the latter must take into account the former.

Keywords:

access; food security; smallholders; Kenya; Mount Kenya; farm technology; theory of access 1. Introduction

1.1. Access to Productive Resources and Food Security

Concern for food security has put agriculture back in the spotlight, following three successive food price crises in 2007, 2011, and 2018 [1,2]. Globally, smallholder farming supports many of the most vulnerable people and is crucial to producing most of the world’s food [3,4,5,6]. This is no different in Kenya: Over 80% of Kenya’s population derive their livelihoods from agriculture; the majority farm on plots that are smaller than 2 ha [7].

Productive resources such as land and water are fundamental to households that rely on crop and livestock production for their livelihoods [8]. However, access to land and water is becoming more tenuous for many poor households in rural areas of developing countries [9], particularly in Kenya [10]. Small-scale farmers face many challenges such as inadequate access to financial resources, quality inputs, high transaction costs due to poor infrastructure, and land and water tenure insecurity. All of this limits their access to productive resources and prevents them from scaling up their market participation, plunging them into poverty and making them food insecure.

Initial conceptualizations of the relation of tenure security with productive resources and food security put the two within a linear framework that begins with access to resources and proceeds causally from production through consumption and finally to a food security status [11]. Such studies argue that enhanced tenure security enables efficient, profitable, and sustainable agricultural production, leading to greater income and food security. However, there is little evidence on how resource owners’ access to productive resources is also dependent on aspects beyond land tenure security. There is also the matter of the definition of “access”.

Access to natural resources is often viewed mainly as a function of private property rights [12,13,14,15]. It is often assumed that being in possession of private property rights enhances agricultural productivity as it incentivizes farmers to invest in, and make efficient use of, their land [12]. It also allows them to transfer or use private property rights as collateral in the formal credit market [13,14]. However, empirical studies have shown that access to land, water, or other natural resources is not just a matter of assured (private) property rights [8,16,17,18]. Political ecology points out that institutions, power, and diversity in natural resource governance largely determine access to, and use of, land and other resources. Hence, access to natural resources and the degree to which it can be translated into economic benefits largely depends on the position of rural households within the reigning power relations at household to international levels [19].

In such a perspective, “access” must go beyond the classical definition of “the right to benefit from things” to also incorporate “the ability to derive benefits from things” [15]. This involves differentiating “access” from “property”. “Access” is dependent on a broad set of factors (a “bundle of powers”) involving constellations of means, relations, and processes which, together with a “bundle of rights” (formal and informal property rights to productive resources such as land and water), enable various actors to derive benefits from resources. Thus, while a farmer may be a landowner with a title deed, he or she may fail to benefit from the land due to a lack of knowledge, labour, or networks to sell the produce.

The Theory of Access conceptualizes how configurations of bundles of private property rights and bundles of powers shape access to resources and how this access is gained, maintained, and controlled [15]. We chose this theory because it offers a comprehensive framework for examining the role of access in understanding household food security—which represents one livelihood outcome—through interactions between the bundle of (private property) rights and bundle of powers. Sustainable livelihood outcomes are achievable through the ability to gain, maintain, control, and enhance resources on which livelihoods depend. Guided by the Theory of Access, we aim at identifying the main factors in the respective bundles of rights and powers that enable rural households to derive benefits from their productive resources and thus, to achieve household food security.

1.2. Theory of Access, Bundles of Rights and Powers, and the Link to Food Security

The Theory of Access differentiates between one’s right to access resources and one’s ability to benefit from these. Ribot and Peluso [15] argue that people may hold the right to access a certain resource, but may not necessarily have the ability to use the resource in a productive way to benefit from it due to a lack of structural and relational mechanisms such as capital, technology, labour, knowledge, authority, market mechanisms, social relations, and identity. McKay and Colque [18] point out that having the ability to benefit from resources involves access mechanisms that go beyond legal rules or titles and that lacking such mechanisms results in exclusion. So, for example, a farmer may have the right to use the land but lack access to labour or capital to hire labour.

Ribot and Peluso [15] analyse access along the two variables of “bundle of rights” and “bundle of powers”. While the former embraces all types of formal and informal rules or norms, the latter denotes the structural and relational mechanisms of access that influence whoever gains, maintains, and controls benefits from resources. Thus, according to the theory, bundles of powers mediate or operate in parallel to rights-based access mechanisms to shape how resource users gain control and maintain benefits.

This broad definition of access helps us differentiate in this study the importance of property rights and to acknowledge the role of structural and relational access mechanisms that enable households to gain, maintain, and control access to productive resources. For smallholder farmers, access to land is the most important resource for agricultural production, followed by water for irrigation. Irrigation water helps agricultural crop growth and reduces the effects of inadequate rainfall. Gaining access to productive resources can enable smallholder farmers to adopt sustainable land management approaches such as water-saving strategies and nutrient management, which are needed to achieve sustainable livelihoods by increasing productivity and adapting to and mitigating climate change [20]. A livelihood is a means of securing the necessities of life and one necessity or outcome is the achievement of food security. Limited access to productive resources makes smallholder farmers vulnerable to food insecurity and results in unsustainable livelihoods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

We chose the north-western slopes of Mount Kenya as a study area for two reasons: First, we sought an area that represents smallholder family farmers whose main livelihoods depend on crop and livestock production. The majority of the households in this area are small-scale farmers practising mixed farming on less than 1 ha of land [21]. Crop failure and lack of pasture are common in the area due to frequent droughts and erratic rainfall [22].

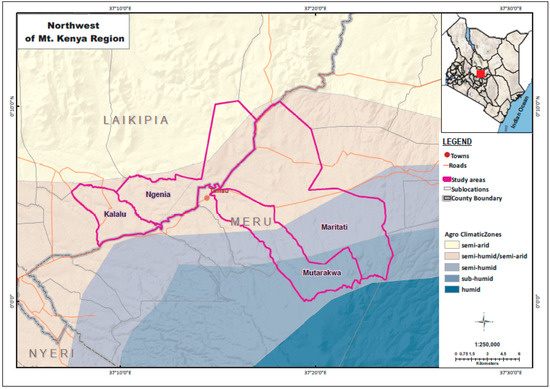

Second, we sought an area of which its agro-ecological conditions led to the use of water for irrigation. We conducted the study on the north-western slopes of Mount Kenya, covering parts of Laikipia and Meru counties, within the upper Ewaso Ng’iro basin (Figure 1) from June to November 2018. The study area is characterized by a steep ecological gradient marked by distinct altitudinal belts that drop from an imposing height of 5200 m in the alpine zone through the Laikipia plateau at 1500 m to below 1000 m in the Samburu lowlands [23]. The climate changes from semi-humid (1000–1500 mm annual rainfall) in the highlands of Meru County to semi-arid (400–700 mm annual rainfall) and to arid (about 350 mm annual rainfall) northwards over the Laikipia Plateau [24].

Figure 1.

Study area: north-west of Mt Kenya (Centre for Training and Integrated Research in ASALs Development, 2019).

The study sampled two adjoining areas to capture the ecological gradient: humid to semi-humid conditions with an average annual precipitation of 900 mm–1200 mm, with Kalalu and Ngenia receiving slightly less than the upper parts of Maritati and Mutarakwa (Figure 1). This gradient represents declining precipitation and water resources. Coupled with population increase, this decline greatly impacts access to water for irrigation due to high demand [25]. The area experiences two rainy seasons, March to May and October to November rains. Rains are irregular and erratic in terms of onset, period, and end due to climate variability [25].

2.2. Data Collection

We collected data through 76 semi-structured household surveys and eight key informant interviews. The households that were studied comprised 38 food secure and 38 food insecure households, which were a sub-sample from a database of 380 households developed by the authors of a food security survey in the region [26]. This survey included households in three ecological zones: humid, semi-humid, and semi-arid. To capture water use for irrigation, we selected 380 households in the humid and semi-humid region. From these households, 183 were food secure and 197 were food insecure. The study sampled 20% of all the households, resulting in 76 households for in-depth qualitative analysis of strategies of land and water access. For equal representation, we systematically selected every fifth food secure and insecure household. Finally, we interviewed the sampled households about the factors of bundle of rights and powers, guided by the Theory of Access on Table 1.

Table 1.

State of the art for the variables forming the bundle of rights and powers.

Five common food security indicators were used to determine the food security status of the sampled households: Household Dietary Diversity Score [40], Food Consumption Score [41], Coping Strategy Index [42], Household Food Insecurity Access Scale [43], and Months of Inadequate Food Provisioning [44]. To capture the overall food security status of each household, the authors checked whether the household met the food security thresholds for each of the five indicators. Mutea et al [26] used the food security thresholds of respective indices to group food secure and insecure households.

2.3. Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed and coded before undergoing content analysis [45,46]. Second, we rated each mechanism of access represented by the bundles of powers and rights according to Ribot and Peluso [15], see Table 2. The rating used an ordinal Likert scale from 0 to 3, defined and determined individually for each variable displaying inexistence, low, medium, and high matching with the variables as found at the household level [47]. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to test how well the mechanisms of access correlate, see Equation (1). Fischer’s exact test was carried out to test the statistical significance of any observed difference, see Equation (2) [48].

where is Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, n is the number of observations of the two groups of households and is the difference in the ranks of the ith household of each random variable considered. The Spearman correlation coefficient, p, can take values from +1 to −1.

where a, b, c, d, e, and f are the number of households in each cell and n is the total number of households. The Fisher Exact test uses this formula to obtain the probability of the combination of the frequencies.

Table 2.

Indicators and weighting criteria for rights and power-based access to productive resources.

2.4. Characteristics of Studied Population

Table 3 shows the characteristics of the sampled 76 households split into two subsets. Food secure and insecure households are equally represented, allowing comparison between these two groups.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studied population.

3. Results

3.1. Access Mechanisms by Food Secure and Insecure Households

From the overview on Table 4, access to technology was the only factor among the bundle of powers that showed a statistically significant difference between the two types of households. Access to technology had a moderately high score among the food secure households and a low to medium score among the food insecure households.

Table 4.

Scores for food secure and insecure households with Fisher’s exact test showing the statistical significance between food security status and factors of bundle of rights and power.

Food secure households had an average of 10 different small hand tools and food insecure households had 7. Food secure and insecure households needed the small hand tools for most of their labour-intensive farm work such as planting, weeding, spraying, slashing, and harvesting. Food secure households had the ability to purchase more hand farm tools, and some were able to buy additional farm implements (farm implements are bigger than hand tools and are animal or power driven) such as a harrow, thresher, or plough (Table 5). Food secure and insecure households reported that small hand tools such as spades, hosepipes, fork jembes, machetes, hoes, and slashers were cheaper (hence owned, on average, by 85% of the food secure households and 69% of the food insecure households) than farm implements (owned by a few food secure households). Additionally, small hand tools require low maintenance and make farm work easier, faster, and more efficient. It is worth mentioning that despite small hand tools being cheaper than farm implements, both food secure and insecure households still struggled to afford the tools. This meant that some households from both groups had to acquire tools on credit or rely on renting and borrowing.

Table 5.

Type of tools and implements owned by food secure and insecure households.

In addition to owning small hand tools, some food secure households had managed to purchase power driven or animal driven farm implements. These implements cost more, need a higher level of servicing and maintenance, and are mostly used for land preparation. In addition to food secure households using some of these implements on their farms, they earned additional income by renting them out to other food secure and insecure households. Renting of farm implements such as tractors, ox-drawn ploughs, and chaff cutters was preferred by most of the households in both groups because it was more affordable than buying. Food secure households were timely in carrying out their agricultural work, as they owned a variety of farm tools and implements. Households that needed to borrow or rent tools and implements experienced delays in carrying out their agricultural works if a particular tool or implement was in use by the owner or rented out to other farmers.

3.2. Correlation Between Household Food Security and the Bundle of Rights and Powers

Table 6 provides more detail on how access to technology is related with other aspects of bundles of rights and powers. The access to technology of food secure households had a significant positive correlation with access to authority. Social–political relations with the authorities in the local and county government, mainly through extension services, facilitated access to technologies by creating awareness of these technologies and in demonstrating and providing training on their use. For every improved or new farm technology introduced to households, e.g., conservation agriculture, mulching, or irrigation, the households were also educated on the appropriate farm tools and implements.

Table 6.

Correlation coefficients and the statistical significance of the interaction between bundle of rights and bundle of power (values with * indicate statistically significant correlations. P-values are shown on Supplementary Material Table S1).

According to the extension officers, a household wanting to adopt conservation agriculture must have access to tools for minimum tillage, direct seeding, and weed management. Minimum tillage tools include rippers, subsoilers, and chisel ploughs to break the hard pan and confine the tillage to where the crop is planted. Jab or animal drawn planters, hoes, and planting sticks are necessary for direct seeding, while weed management requires shallow weeders and sprayers. In another example, a household wanting to practice mulching needs access to a garden fork to lift mulch, a wheelbarrow to transport the mulch, and a rake for even application. A simple overhead irrigation system requires hosepipes, sprinklers, and sometimes water pumps.

In an interview, a Ministry of Agriculture representative pointed out that government extension services were demand driven and took a group approach. Therefore, food secure and insecure households are usually encouraged to form groups, decide on the type of training they wish to receive, and then invite the extension officers to give the training. However, many of the households struggle to afford the required tools and implements, and the government of Kenya currently has no subsidy programme to support them in accessing these.

Access to technology was significantly negatively correlated with social relations: having fewer tools and implements makes it even more important to have a good social network. We observed three main ways in which food secure households put to use social relations to access farm tools and implements: purchasing (sometimes on credit), renting, and borrowing. Therefore, cultivating good social relations with business owners, fellow farmers, and neighbours was a strategy that enabled them to access tools and implements.

In addition, we identified other significant relationships that enabled food secure households to access their productive resources. Formal rights-based access to land is negatively correlated with informal rights-based access and labour and labour opportunities. Both food secure and food insecure households’ preferred formal rights-based access as it offered greater tenure security than informal rights-based access. There is a significant negative correlation between informal rights-based access and access to technology. Our in-depth interviews revealed that both groups preferred to adopt farming technologies with long-term impacts (e.g., mulching, conservation agriculture) on land to which they had formal rights-based access in the form of a freehold title deed. Having a freehold title deed gave them an incentive to invest for the future, in contrast to a rental contract, which offered only short-term tenure security.

Access to water among the food secure households was significantly positively correlated with access to capital, technology, authority, and knowledge. A majority of both groups (87% of food secure and 76% of food insecure households) accessed water for irrigation through membership in community water projects (CWPs). CWP committees control membership and water access. Access to water officials thus played an important role in gaining and maintaining access to the CWPs, especially when joining the CWP or during water disputes such as unauthorized disconnection. Another factor influencing access to water is capital, which enabled households to pay water installation fees and water bills. Moreover, in efforts to maximize the availability of water and use of water efficiently, some food secure households adopted water conservation technologies such as drip irrigation. Knowledge of such technologies was in some cases gained through extension services or off-farm employment, mainly on the horticulture farms.

Access to capital is significantly influenced by access to technology, authority, and knowledge, and through social identity. The most common strategy used to stabilize access to financial resources among the food secure households was through social identity, in groupings such as rotation savings and credit associations (ROSCAs), using systems such as “merry-go-round” or table banking. Food secure households whose members had the necessary skills and knowledge were able to secure off-farm employment. Most employers, such as horticulture farms and government jobs, required employees to open bank or Sacco accounts, through which such households were able to secure their capital in the form of savings and credit. Food secure households had more capital, which enabled them to purchase more tools and implements. Access to capital enabled households to access authorities, especially those who needed inducement, especially for land and water dispute resolution.

Access to labour and labour opportunities is positively influenced by access through social identity. Besides family labour, 89% and 47% of the food secure households had additional farm workforce and off-farm jobs, respectively. From our interviews, we found that households had formed groups for exchanging labour. During routine meetings in various social groupings, households had an opportunity to share their farm labour concerns and met people with similar experiences. From such encounters, they formed support groups for reciprocal labour exchanges. Social groupings also acted as venues for getting information on new job opportunities or creating networks for information sharing. Hence, the positive significant correlation between access through social identity and access to knowledge.

4. Discussion

Guided by the Theory of Access by Ribot and Peluso [15], and understanding “access” as spanning the property rights to benefit from resources on the one hand to the ability to benefit on the other, we explored how bundles of rights and powers relate to food secure and food insecure households. According to our findings, the only statistically significant difference between the two types of household, in terms of rights or powers held, was access to technology in the form of productive farm tools and implements. Moreover, access to technology was significantly positively correlated with access to authority and negatively correlated with access through social relations. Access via social identity has a significant influence on access to capital, labour and labour opportunities, and knowledge. Access to knowledge and authority enable food secure households to access capital and water. Access to water was significantly positively correlated with access to capital.

In Kenya, many households are trapped into food insecurity due to low productivity resulting from the inability to afford modern technologies; an overreliance on red-fed agriculture, in particular, is a major contributor to food insecurity [49]. Not only do farm tools and implements enhance production efficiency and make farm work easier [50], they are crucial in semi-subsistence agriculture to access productive resources, especially land and water. Smallholders can quickly adopt farm technologies such as irrigation if tools for implementation are readily available and accessible [31].

Government extension services play a key role in creating awareness and in disseminating new farming technologies [51,52]. Access to extension services encourages farmers to adopt technologies, such as farm diversity, by raising awareness of new and existing technologies and improving knowledge on how to manage them [52]. Social groupings can enhance farmer organizational empowerment, enabling farmers to express informed demands for agricultural extension and research services [53]; government extension services in Kenya are now adopting the approach of encouraging social groupings. There are also private extension services offered by commercial companies for profit; these often target farmers with relatively high income because they can afford to pay them [52].

In Kenya, a lack of money has often prevented households from adopting farm technologies such as soil erosion and conservation measure [49,54]. Our study confirmed the importance of social relations (as in Okoba and Graaf [54]) in maintaining access to technology, either on credit or through renting or borrowing.

Another factor that influences the adoption of technologies such as conservation agriculture in Kenya is land tenure security [55]. While the households in our study rarely made use of their private property rights as collateral for credit, they benefitted from this tenure security to make investments on their land. However, not every formal rights-based access gives an incentive to make long-term investments. For example, in Kenya, farmers who use plots temporarily are not motivated to make long-term investments (e.g., application of organic fertilizer, conservation agriculture) because they cannot fully recoup the investment [28,55,56]. Muraoka et al. [28] also found that rented plots are less productive than owned plots, but they still contribute to household food security.

Social identity is another important factor that enables food secure households to improve access to productive resources. Joining social groupings such as ROSCAs allows households to access information and credit during periods of low capital flow. They can thus continue to pay their water bills, for example, maintaining access to this resource. Ulrich et al. [25] highlights that households prefer to access financial assistance and credit through ROSCAs rather than through commercial banks as there are fewer hurdles such as the need for collateral or the high interest rate. Moreover, individuals feel more comfortable sharing knowledge and information with people of a similar social identity than with people with whom they do not share a social identity [57]. Social identity is often used by households as a means of maintaining access to productive resources, such as through labour sharing arrangements [58].

5. Conclusions

This study explored household food security through the lens of the Theory of Access, an application that was not yet covered in depth in the literature. We found that a lack of tenure security is not the only reason for food insecurity of households. Most of the farmers in this study were in possession of and were able to benefit from the property rights to their productive resources. Instead, the main problem appeared to be difficulties in accessing the technology needed to unlock further benefits from households’ productive resources, making these households vulnerable to food insecurity. Access to authority and social relations play a key role in enabling access to technology.

Thus, there is a need to improve access to technology—especially among farmers with no access to authority or social relations—to enable rural households to maximize labour productivity and adopt the farm technologies they need for, for example, drip irrigation, conservation agriculture, mulching, and overhead irrigation. Small hand tools that are required include sprayers, shallow weeders, and sprinklers; larger farm implements needed include rippers, drip kits, water pumps, and chisel ploughs. Moreover, farmers should be encouraged to form groups to increase their chances of accessing government extension services.

The present study only investigated factors that shape access according to the Theory of Access. The data we obtained could not fully explain how some factors in the bundle of rights and powers influence each other or correlate. We therefore propose that further research explores the proximate and underlying factors that influence the mechanisms of access to productive resources. For instance, how does access to labour, and to labour opportunities, influence rights-based access to land? Or, how does the gender of the head of household influence the mechanisms used to access resources and, ultimately, food security?

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/5/1751/s1, Table S1: Statistical significant levels at P = 0.05 threshold of the correlation coefficients between mechanisms of access to land and water.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design, E.M. and S.R.; Methodology, E.M. and S.R.; Formal Analysis, E.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.M.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.J. and S.R.; Supervision, S.R.; Project Coordination, J.J.; Funding Acquisition, E.M.; S.R.; and J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The main author received support from the Swiss Government Excellence Scholarships for Foreign Scholars and Artists: ESKAS 2017.0930 and the co-authors received support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through the Swiss r4d programme, grant number: SNSF 400540-152033. We also benefited from the Bern University Research Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the households in the Mount Kenya region that took part in this study and the Centre for Training and Integrated research in ASALs Development (CETRAD) for facilitating the research. We thank Boniface Kiteme and Chinwe Ifejika Speranza for their constructive inputs to the manuscript and we thank Tina Hirschbuehl for editing the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all the sampled population before the study. The participants were informed that their contribution was anonymized and only used for research purposes. Ethical approval was not sought for the present study because it is not required as per the University of Bern guidelines and applicable national regulations.

References

- African Smallholder Farmers Group. Supporting Smallholder Farmers in Africa: A Framework for an Enabling Environment; African Smallholder Farmers Group: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Food Security Information Network. Global Report on Food Crisis 2018. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000069227/download/?_ga=2.244174085.1862504590.1582542458-1500710275.1566571088 (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Samberg, L.H.; Gerber, J.S.; Ramankutty, N.; Herrero, M.; West, P.C. Subnational Distribution of Average Farm Size and Smallholder Contributions to Global Food Production. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Mehrabi, Z.; Jarvis, L.; Chookolingo, B. How Much of the World’s Food Do Smallholders Produce? Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeub, B.E.; Chappell, M.J.; Wittman, H.; Ledermann, S.; Kerr, R.B.; Gemmill-Herren, B. The State of Family Farms in the World. World Dev. 2016, 87, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Gĩthĩnji, M.W. Small Farms, Smaller Plots: Land Size, Fragmentation, and Productivity in Ethiopia. J. Peasant Stud. 2018, 45, 757–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakawuka, P.; Simon, L.; Petra, S.; Jennie, B. A Review of Trends, Constraints and Opportunities of Smallholder Irrigation in East Africa. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 17, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Po, J.Y.T.; Gordon, M.H. Local Institutions and Smallholder Women’s Access to Land Resources in Semi-Arid Kenya. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 252–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Savastano, S.; Xia, F. Smallholders’ Land Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: A New Landscape? Food Policy 2017, 67, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, T.S.; Muyanga, M. Land Constraints in Kenya’s Densely Populated Rural Areas: Implications for Food Policy and Institutional Reform. Food Sec. 2012, 4, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maxwell, D.; Wiebe, K. Land Tenure and Food Security. Dev. Chang. 1999, 30, 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenaw, S.; Islam, K.M.Z.; Parviainen, T. Effects of Land Tenure and Property Rights on Agricultural Productivity in Ethiopia, Namibia and Bangladesh; University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bugri, J.T.; Yeboah, E. Understanding Changing Land Access and Use by the Rural Poor in Ghana; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cordoba, G.I. Land Property Rights and Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from Panama. In Responsible Land Governance: Towards an Evidence Based Approach. Annual World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty; Center for Data Science and Service Research: Sendai, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ribot, J.C.; Peluso, N.L. A Theory of Access. Rural Sociol. 2003, 68, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, L.; Rist, S. Seeing Land Deals through the Lens of the ‘Land–Water Nexus’: The Case of Biofuel Production in Piura, Peru. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasselle, A.-S.; Gaspart, F.; Platteau, J.-P. Land Tenure Security and Investment Incentives: Puzzling Evidence from Burkina Faso. J. Dev. Econ. 2002, 67, 373–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, B.; Colque, G. Bolivia’s Soy Complex: The Development of ‘Productive Exclusion’. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 43, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.L. Progress in Physical Geography Power, Knowledge and Political Ecology in the Third World: A Review. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1998, 1, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liniger, H.; Studer, R.M.; Hauert, C.; Gurtner, M. Sustainable Land Management in Practice Guidelines and Best Practices for Sub-Saharan Africa; TerrAfrica, World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2011. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i1861e/i1861e00.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Zaehringer, J.G.; Wambugu, G.; Kiteme, B.; Eckert, S. How Do Large-Scale Agricultural Investments Affect Land Use and the Environment on the Western Slopes of Mount Kenya? Empirical Evidence Based on Small-Scale Farmers’ Perceptions and Remote Sensing. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 213, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejika Speranza, C. Buffer Capacity: Capturing a Dimension of Resilience to Climate Change in African Smallholder Agriculture. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiteme, B.P.; Gikonyo, J. Preventing and Resolving Water Use Conflicts in the Mount Kenya Highland–Lowland System through Water Users’ Associations. Mt. Res. Dev. 2002, 22, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, S.; Kiteme, B.; Njuguna, E.; Zaehringer, J.G. Agricultural Expansion and Intensification in the Foothills of Mount Kenya: A Landscape Perspective. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, A.; Ifejika Speranza, C.; Roden, P.; Kiteme, B.; Wiesmann, U.; Nüsser, M. Small-Scale Farming in Semi-Arid Areas: Livelihood Dynamics between 1997 and 2010 in Laikipia, Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutea, E.; Bottazzi, P.; Jacobi, J.; Kiteme, B.; Speranza, C.I.; Rist, S. Livelihoods and Food Security Among Rural Households in the North-Western Mount Kenya Region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Kenya. National Land Use Policy; Government of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017.

- Muraoka, R.; Jin, S.; Jayne, T.S. Land Access, Land Rental and Food Security: Evidence from Kenya. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Kenya. The Water Act; Government of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016.

- Ifejika Speranza, C.; Kiteme, B.; Wiesmann, U.; Jörin, J. Community-Based Water Development Projects, Their Effectiveness, and Options for Improvement: Lessons from Laikipia, Kenya. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2018, 37, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizimana, J.-C.; Richardson, J.W. Agricultural Technology Assessment for Smallholder Farms: An Analysis Using a Farm Simulation Model (FARMSIM). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejika Speranza, C.; Kiteme, B.; Wiesmann, U. Droughts and Famines: The Underlying Factors and the Causal Links among Agro-Pastoral Households in Semi-Arid Makueni District, Kenya. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduol, J.B.A.; Kyushu, U.; Hotta, K.; Shinkai, S.; Tsuji, M. Farm Size and Productive Efficiency: Lessons from Smallholder Farms in Embu District, Kenya. J. Fac. Agric. Kyushu Univ. 2006, 51, 449–58. [Google Scholar]

- Okech, S.H.O.; Gaidashova, S.V.; Gold, C.S.; Nyagahungu, I.; Musumbu, J.T. The Influence of Socio-Economic and Marketing Factors on Banana Production in Rwanda: Results from a Participatory Rural Appraisal. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2005, 12, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, J.R.; Kohler, H.-P.; Watkins, S.C. Social Networks and Changes in Contraceptive Use over Time: Evidence from a Longitudinal Study in Rural Kenya. Demography 2002, 39, 713–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A. The Power of Reciprocity: Fairness, Reciprocity, and Stakes in Variants of the Dictator Game. J. Confl. Resolut. 2004, 48, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiba, M.; Collinson, M.; Hunter, L.; Twine, W. Social Capital Is Subordinate to Natural Capital in Buffering Rural Livelihoods from Negative Shocks: Insights from Rural South Africa. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 65, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, S.S.; Catacutan, D.; Ajayi, O.C.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nieuwenhuis, M. The Role of Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions in the Uptake of Agricultural and Agroforestry Innovations among Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2015, 13, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeni, L.; Moeletsi, M.; Thavhana, M.; Randela, M.; Mokoena, L. Barriers Affecting Sustainable Agricultural Productivity of Smallholder Farmers in the Eastern Free State of South Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide; FHI 360/FANTA Version 2; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Food programme. Food Consumption Score Nutritional Quality Analysis Guidelines (FCS-N); United Nations World Food Programme, Food Security Analysis (VAM): Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D.; Caldwell, R. The Coping Strategies Index. In A Tool for Rapid Measurement of Household Food Security and the Impact of Food Aid Programs in Humanitarian Emergencies, 2nd ed.; Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere, Inc. (CARE): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide; FHI 360/FANTA Version 3; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bilinsky, P.; Swindale, A. Months of Adequate Household Food Provisioning (MAHFP) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide; FHI 360/FANTA Version 4; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2000, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Göb, R.; McCollin, C.; Ramalhoto, M.F. Ordinal Methodology in the Analysis of Likert Scales. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.H. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 2nd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kiriti-Nganga, T.; Mugo, M.; Bonanomi, E.B.; Kiteme, B. Impact of Economic Regimes on Food Systems in Kenya; Discussion Paper; Centre for Development and Environment (CDE), University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, A. Equipment and Tools for Small-Scale Intensive Crop Production. Encyclopedic Dictionary of Landscape and Urban Planning. Natl. Cent. Appropr. Technol. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitonga, S.; Mukoya, W.S.M. An Evaluation of the Influence of Information Sources on Adoption of Agroforestry Practices in Kajiado Central Sub-County, Kenya. Univers. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 4, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwololo, H.M.; Nzuma, J.M.; Ritho, C.N.; Aseta, A. Is the Type of Agricultural Extension Services a Determinant of Farm Diversity? Evidence from Kenya. Dev. Stud. Res. 2019, 6, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis-Hansen, E. Concepts and Experiences with Demand Driven Advisory Services: Review of Recent Literature with Examples from Tanzania; DIIS Working Paper No. 2004/7; Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Okoba, B.O.; Graaff, J.D. Farmers’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Soil Erosion and Conservation Measures in the Central Highlands, Kenya. Land Degrad. Dev. 2005, 16, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hulst, F.J.; Posthumus, H. Understanding (Non-) Adoption of Conservation Agriculture in Kenya Using the Reasoned Action Approach. Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Jayne, T.S. Land Rental Markets in Kenya: Implications for Efficiency, Equity, Household Income, and Poverty. Land Econ. 2013, 89, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.A.; Argote, L.; Levine, J.M. Knowledge Transfer between Groups via Personnel Rotation: Effects of Social Identity and Knowledge Quality. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 96, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczberski, G.; Curry, G.N.; Bue, V.; Germis, E.; Nake, S.; Tilden, G.M. Diffusing Risk and Building Resilience through Innovation: Reciprocal Exchange Relationships, Livelihood Vulnerability and Food Security amongst Smallholder Farmers in Papua New Guinea. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).