Abstract

This study explores the relationship between corporate performance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives in the Ecuadorian banking environment. The first model employs both return on assets and return on equity as proxy for the financial performance while the second model includes the non-financial corporate performance constructs collected by a self-designed online questionnaire. We found a statistically positive relationship among CSR initiates and the financial and non-financial indicators in corporate performance. Our findings revealed that economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibility initiatives positively affect the non-financial corporate performance of the Ecuadorian banking environment. Similarly, the non-financial corporate performance is significantly positively influenced by the customer’s brand trust, customer’s brand loyalty, customer’s perception of quality, and customer satisfaction. Study results are mostly consistent with the banking environment of other countries, especially in Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Lebanon. Customers of the Ecuadorian banking environment perceived banks as socially responsible entities and Ecuadorian banks invest resources in CSR activities as a corporate governance policy to increase their financial and non-financial performance. Future research should include a corporate governance index with a CSR component as an independent variable to increase statistical models’ power.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) faces a pivotal management phenomenon in the business literature, combining the notion of customer-based and corporate-level management [1], while CSR activities have been used to address consumers’ social concerns, create a favorable image, and develop a positive relationship with consumers and stakeholders [2]. CSR has primarily been treated as a corporate issue using CSR initiatives to enhance corporate performance. Nowadays, the degree of CSR level is driven by ideological thinking and multi-faced business, increasing the power and positive force of corporations.

In previous studies, only social attention is focused on the financial sector, given that the failure of commercial banks in the financial crisis, which provokes macroeconomic disasters, reduction of consumption, and increased unemployment in the real economy [3]. Some banks were considered “too big to fail” during the global financial crisis in 2008, since the financial system suggests that, as a last resort in deposit insurance and lending, the integration of more management tools, as well as the guarantee of the banking industry, through the intervention of the federal bank. Several public and private institutions recognized that CSR plays an important role in the moral failure of the financial system, which affects directly the banking system’s reputation and the effective and efficient communication with their stakeholders, classified into three basic groups: Customers, employees, and community [4]. All these factors positively influence earnings, faith, trust, and customer retention of the banking industry [3,5,6]. Specifically, firms with CSR initiatives are more likely to show positive earnings surprises, affecting their returns and equity performance in the short-term by factor-adjusted abnormal returns, which also show a positive effect on CSR reputation [7]. Therefore, banks and financial organizations adopt CSR practices to be beneficial for society and sustainable economic development.

Similarly, CSR can be considered as an important determinant in the progress of the Ecuadorian economic market, especially, in the banking industry. Ecuador reached economic growth and oil bonanza during the period of 2000–2017. Barriga-Yumiguano et al. [8] examined the relationship between financial development and economic growth in Ecuador for the period 2000–2017. They show that the Ecuadorian financial development using the deepening of deposits and credits increased from 20.3% and 19.2% (2000) to 40.4% and 35.1% (2017), respectively. Furthermore, the level of bank usage, called “bankization” presents a growing trend over time, rising from 39.0% (2005) to 96.9% (2017), meaning that less than 4% of the Ecuadorians do not access this basic financial instrument. Moreover, the coverage of Ecuadorian financial institutions between the period of 2000–2017, presents an equal growing trend, increasing from 1966 attention points (2000) to 13,598 attention points (2017), suggesting that there are 16.2 attention points for every 20 thousand Ecuadorians. Unfortunately, CSR has not been investigated enough in Ecuador, specifically in the banking industry. Freire et al. [9] investigated the relationship between CSR and the economic profitability through an analysis of variance using a sample of 25 companies registered in the Ecuadorian Consortium for Social Responsibility during the period of 2013–2015. They presented a positive effect between CSR and the net profit, concluding that the CSR investment maximizes the economic revenue in the Ecuadorian firms.

In this context, the purpose of this study is to identify and explore the relationship between corporate performance and CSR in the Ecuadorian banking industry, employing four criteria for social responsibility practices: Economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic. Our paper provides several implications for bank managers and researchers. First, our models of financial and non-financial performance offer a way of highlighting potential gaps between what customers expect and perceive toward a social-responsible bank, identifying social activities promoted by bank managers, and recognizing social issues in the Ecuadorian banking industry. Second, consumers tend to reward those companies with CSR activities by being more loyal and satisfied with them, suggesting that managers should invest more in social and environmental activities. CSR initiatives have a strong effect on the customer perception of service quality, which is also an important attribute for building customer satisfaction. Thus, managerial plans might strategically allocate the company’s financial resources in CSR activities and investments in service quality. We suggest potential sources of improvements of actual CSR strategies to fit CSR activities with customer’s ideas, desires, and needs, given that, CSR is considered a key tool to create, develop, and sustain differentiated brand names.

We research this topic because the banking market in Ecuador requires an innovative range of products for new customer segments, including groups that are not yet fully integrated into society, such as low-income families and micro-businesses in poor areas. This situation represents for the Ecuadorian banks a design challenge for suitable products and provides the opportunity to develop business strategies for microfinance, including the increase of financial education. Furthermore, the incorporation of CSR strategies into the Ecuadorian banking industry might offer the following advantages: Support the development of separate business models for various segments, create higher employee motivation and superior performance levels, generate positive publicity and/or increased brand recognition, encourage sustainable behavior by customers, and increase real benefits for the society as a whole.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR

Bowen [10] is considered the father of CSR. He believes that large corporations have certain obligations to society, due to their economic performance and their effect on peoples’ livelihoods. Therefore, CSR is defined as the set of obligations and policies executed by businessmen to make decisions using actions according to the objectives and values of our society. Similarly, Carroll [11] emphasizes that firms should have responsibilities to society, which are aligned with the principles of ethics, sustainability/triple bottom line, stakeholder management, and corporate citizenship. In the business context, the Committee for Economic Development includes the satisfaction and needs of society as necessary factors to be called responsible corporations with employees, customers, and community.

Sethi [12] classifies the corporate behavior into (i) social obligation or corporate action, which is provoked by market forces and legal constraints, (ii) social responsibility or corporate behavior by social norms, values, and expectations, and (iii) social responsiveness or corporate ability to adapt itself to changes in the market and society. This classification is clearly defined by Carroll [11]. He introduces the CSR pyramid using four areas: Economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic initiatives. In addition, Porter and Kramer [13] divide CSR into four categories, such as a license to operate, moral obligation, reputation, and sustainability. Other authors incorporate and expand the concept and dimensions of CSR, such as community’s and employee’s relations, conscious capitalism, corporate sustainability, social entrepreneurship, and sustainable business development [14,15]. CSR is considered as the key to business strategy through its competitive advantage effect on stakeholder groups, employees, and customers. Therefore, several authors examine the relationship between CSR activities and the organizational effectiveness measured by job satisfaction improvement [16], organizational trust [17,18], customer satisfaction [19,20], and loyalty [21,22,23]. Finally, a recent study conducted by Dunbar et al. (2019) shows that CSR initiatives have a positive effect on CEO pay-risk sensitivity, meaning that compensation contracts are designed using future idiosyncratic’ and firm’ risk information and financial incentives for CEOs [24].

2.2. Corporate Performance Measurement

The firm’s performance measurement systems play a key role in developing strategy by evaluating the achievement of organizational objectives and the methodology to compensate managers. The performance of a firm can be evaluated using financial and non-financial indicators. Both measures include quantitative and qualitative information. Financial metrics are expressed in monetary units, including earnings, profit margin, average order value, return on assets, and others, while non-financial metrics cannot be formulated in monetary units, such as customer satisfaction, market share, category ownership, new product adoption rate, and others. In this study, we focus on the impact of CSR strategies on the corporate performance of the Ecuadorian banking industry, employing financial and non-financial variables to understand financial results and analyze the board of members’ and executives’ policies to improve the financial metrics [25,26].

2.3. CSR and Corporate Performance in the Banking Industry

CSR in the banking industry has been studied deeply. The banking industry is considered one of the most highly regulated economic sectors with standardized services provided by a relatively small number of the market players, which symbolizes the most important reason why banks must be customer-oriented [27,28,29]. The banking sector decisions affect an outsized number and various individuals due to the complex information asymmetry among the economic agents. Banks are considered to have key influence on sustainability, and their efforts to build a better society are currently communicated to society to maintain and reinforce their reputation and customer relationship [30,31]. The most important social function of the financial institutions is their intermediary role, which channels savings into investments, protecting the interests of depositors and owners. CSR practices in the banking sector emphasizes responsibility in the areas of loan, investment, and asset management, combined with key elements of anti-corruption and money laundering. Applying Carroll’s CSR model in the financial sector, Decker and Sale [32] summarize the following aspects: firstly, economic responsibility is that the main goal for banks is to improve the stakeholders’ welfare, profitability, and growth. Banks employ financial innovation to cover individual requirements and corporate financial interests, which are constantly changing factors. The banking sector creates new opportunities for risk management and develops fresh products through interaction with stakeholders; secondly, legal responsibility is that the banking industry is one of the safest economic sectors with high regulation level, which minimizes risk and increases confidence in the financial system for the parties. Therefore, statutes, supervisory bodies, controlling public and private entities provide guidelines on internal and external governance at the national and international levels; thirdly, ethical responsibility is that ethical standards might be understood through individual integrity and the stakeholder’s expectations. Each bank promotes basic ethical principles to increase its customer’s trust, represented by the code of ethics that represents controlled restrictions and fundamental principles such as integrity, fair conduct, respect, and transparency in the market; fourthly, discretionary (philanthropic) responsibility is that Bank’s business activities and clientele increase the reputation of the financial sector, including secure products and appropriate information provision. The direct environmental impact of the bank’s operations and bank’s lending activities are important factors for the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), promoting the “inclusive finance” for vulnerable classes.

Based on the theoretical background and previous studies, we develop our first set of hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Corporate performance is positively affected by CSR initiatives.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Corporate performance is positively affected by economic responsibility initiatives.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Corporate performance is positively affected by legal responsibility initiatives.

Hypothesis 1d (H1d).

Corporate performance is positively affected by ethical responsibility initiatives.

Hypothesis 1e (H1e).

Corporate performance is positively affected by discretionary (philanthropic) responsibility initiatives.

2.4. CSR and Customer’s Brand Trust

Customers’ brand trust is defined as joint beliefs, goals, and policies, which are significant and appropriated for both customers and firms, while a company can gain benefits and increase its profits through customer loyalty, positive brand attitude, and customer trust. Existing values are shared by customers and companies, creating goals in common between these two parties. The welfare of customers is the result of the effort of a company as its signal of trustworthiness. Customer’s trust might be positively influenced by CSR programs, given that, these activities reduce the inherent uncertainty in transactions. CSR activities increase repurchase intention, customer loyalty, and trust [33,34]. Therefore, our second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Customer’s brand trust is positively affected by CSR initiatives.

2.5. CSR and Customer’s Brand Loyalty

Customer’s brand loyalty is described as the commitment to re-purchase or re-use a desired product or service consistently in the future, so that it causes re-purchase of the same brand or the same brand-set [2]. Customer loyalty is the relationship between the relative attitude towards a brand and patronage behavior for developing a sustainable competitive advantage. Furthermore, it is the degree of customers’ preference between one company and its rivals, expressed by repeated purchasing behavior, which is one of the most important challenges for firms. A consumer re-purchases a company’s product when the customer is convinced of and identified with the company’s CSR performance [35]. Furthermore, loyalty retention is treated as a key factor in conveying long-term business profitability because profits might be affected over the lifetime of a customer through his/her retention [36,37]. Empirical studies show that brand loyalty (i) has a positive effect on profit [38], (ii) reduces the marketing costs [39], (iii) decreases the cost of customer retention [40], and (iv) positively affects by word-of-mouth recommendation [41]. Thus, our third hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Customer’s brand loyalty is positively affected by CSR initiatives.

2.6. CSR and Customer’s Perception of Service Quality

Quality of service represents the difference between expectations about a product or service and a perception of how the product or service works [42]. Empirical studies found a positive relationship between service quality and CSR initiatives because customers recommend the company to others when their perceptions of service quality are increased by the introduction of CSR practices on a firm [17]. Furthermore, service quality is more positively related with the willingness to pay for a particular product or service, which affects the price elasticity [43]. Therefore, our fourth hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Customer’s perception of service quality is positively affected by CSR initiatives.

2.7. CSR and Customer Satisfaction

Satisfaction summarizes the consumers’ experience when they buy a product or service. A positive image of a company generates an optimistic effect on the costumer satisfaction level. CSR is considered as the major determinant in the corporate image increase, which leads to higher consumer satisfaction [22,44]. Empirical studies indicate a direct positive correlation between CSR and customer satisfaction because customers are potential stakeholders, who evaluate the economic and social performance of the company. Moreover, customer satisfaction is recognized as a necessary input in the corporate strategy and a key factor for long-term corporate profitability [6]. Satisfaction is associated with perceptions of the features of a product or service. Different consumers might express different levels of satisfaction for the same experience [45,46]. Therefore, our fifth hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Customer satisfaction is positively affected by CSR initiatives.

3. Research Model

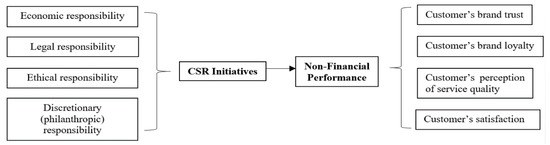

We analyzed the effect of CSR factors on the performance of the Ecuadorian baking industry, using financial and non-financial variables. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the research models for financial and non-financial corporate performance, respectively.

Figure 1.

Model A: Financial corporate performance model.

Figure 2.

Model B: Non-financial corporate performance model.

Measurement of Constructs

We introduced two financial corporate performance models (Equations (1) and (2)). For the financial corporate performance model, we use return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) as the dependent variable, while CSR initiatives are the independent variable.

where is the financial performance for firm i in year t. It is composed of and . for firm i in year t, for firm i in year t, for firm i in year t,

- for firm i in year t, for firm i in year t,

- for firm i in year t, for firm i in year t, is a dummy that represents the year of information of firm i, and is the error term for firm i in year t.

For the non-financial corporate performance model, we designed a survey to identify the effect of CSR factors on the non-financial performance in the Ecuadorian banking industry. Eight constructs were measured in our study: Economic responsibility, legal responsibility, ethical responsibility, discretionary (philanthropic) responsibility, customer’s brand trust, customer’s brand loyalty, customer’s perception of service quality, and customer satisfaction. All constructs were measured using multiple items, and each item employs a five-point Likert scale: 1 for strongly agree and 5 for strongly disagree. Items are adapted from prior literature to ensure content validity. The operational definition of each item is grounded in the CSR orientation aligned with the Carroll’s four-part CSR model. The majority of Ecuadorian private enterprises, including banks, are family-owned businesses, and the conservative owners of these businesses would not easily reveal their actual financial data, especially if these data contain sensitive and classified information. Powell (1992) suggests using subjunctive measures instead of financial metrics because private enterprises would not provide confidential information on their financial statements [6,44]. Thus, we select and design special items of each construct to achieve our research objective. The final list of items for each construct is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Scale items for constructs.

In the literature on corporate finance and accounting, there is concern about the endogenous relationship among variables, which arises when the explanatory variables are correlated with the error term in a regression model and increases the bias and inconsistency in the parameter estimates. Li (2016) shows that the endogeneity problem can be mitigated partially by the generalized method of moments, fixed effects models, lagged independent variables, and control variables [54]. To diminish the endogeneity problem, we include year-fixed effects and size as the control variable in our financial corporate performance model. Furthermore, our dependent variable’s error terms are not normally distributed, because the Pearson correlation matrix between the main variables and the residuals for each model, does not reveal high and significant (at the 5% level) coefficients between variables and residuals [55].

4. Empirical Results

4.1. CSR and Financial Performance

The sources of information are the (i) Ecuadorian Superintendence of Banks, (ii) Association of Ecuadorian Banks, (iii) Ecuadorian Consortium for Social Responsibility, (iv) Ecuadorian Social Responsibility Institute, and (v) a collection of publicly available information and documents on banks’ websites. We collected data from 24 Ecuadorian private banks, using financial measures from the “Managerial Report from Monthly Financial Newsletters—Period 2013–2018” [56]. Extreme observations, missing variables, and incomplete information were excluded [57] from the dataset, resulting in 19 Ecuadorian private banks with 304 firm-year observations.

Table 2 shows the results of four multiple linear regressions using CSR factors that affect the financial firms’ performance measured by ROA and ROE in the Ecuadorian banking industry. ROE models reflect an adjusted R-Square of 0.367 and 0.356 for model 1 and model 2, respectively. ROA models indicate lower values than ROE models with an adjustment of 14.8% and 14.0% for models 1 and 2, respectively. Predictor variables of investment in educational programs, plans of public interest housing, and microenterprise programs do not completely explain ROA and ROE. Therefore, the remaining adjustment percentage can be explained by other independent variables, which are not included in this study.

Table 2.

Regression results: Financial corporate performance—research model A.

The regression coefficient of CSR initiatives indicates that when CSR investment increases by one unit, with the assumption that other variables remain constant, the financial performance of Ecuadorian banks will rise by 0.0001 (ROA model) and 0.0005 (ROE model). In both models, the t-value of CSR initiatives is significant, at least at the 5% level. Furthermore, the regression coefficients of investment in educational programs, housing of public interest programs, and microenterprise programs show a significant positive effect on ROA, while only investment in educational and microenterprise programs evidence a significant positive relationship with ROE. Therefore, hypothesis 1a is accepted for ROA and ROE models, meaning that the financial corporate performance is positively affected by CSR initiatives in the Ecuadorian banking industry. These findings are consistent with Wu and Shen’s (2013) study using data from 162 banks in 22 countries. They suggest that banks with higher CSR investment would show higher financial earnings, better asset quality, and higher financial intermediary’s reputation [47,58]. Furthermore, Djalilov et al. (2015) found a significant positive relationship between CSR practices and bank performance measured by ROA and ROE in 16 transition countries of the former Soviet Union and Central and Eastern Europe. They mention that CSR is primarily a business strategy and banks of transition economies engage in social activities to increase their profits by improving their image by participating in CSR activities [59]. Ashraf et al. (2017) show a positive relationship between CSR and banks’ financial performance in Bangladesh and Pakistan. They found that banks invest in CSR activities as strategic planning for increasing goodwill and reducing promotional costs [60]. Fayad et al. (2017) investigated the effect of CSR on the financial performance of Lebanese banks. Their results reveal that economic, community and human developments have a significant positive impact on ROA, meaning that Lebanese banks attempt to adopt volunteer actions that promote social responsibilities to increase their legitimacy [61].

4.2. CSR and Non-Financial Performance

The questionnaire was distributed and collected using Google Forms, while SPSS 20.0 was employed to identify extreme values or missing data and process all data. A total of 245 questionnaires were recorded. Initial data cleaning found that some responses were duplicated because the web-link was sent for work associates and other professional networks and some respondents might have misunderstood the questions or they completed the questionnaire two times. Those duplicated data and invalid responses were deleted from the database. Hence, a total of 228 records was used for our analysis.

4.2.1. Demographical Analysis

In the statistical characteristics of this study, 51.8% of men and 48.2% of women responded. Their percentage age was distributed as 26–35 years old at 44.7%, 36–45 years old at 25.9%, 18–25 years old at 15.8%, 46–55 years old at 8.8%, and higher than 56 years old at 4.8%. College graduates occupied the highest percentage of respondents (53.9%), 39.9% were masters and doctorate degrees, and 6.2% were junior college graduates. Private employees represented 59.2% of the total respondents, while 29.4% worked in the public sector, and the remaining percentage (11.4%) worked by themselves (own job). Most of the surveyed (82.5%) saved and invested money in an Ecuadorian private bank, and 17.5% had a bank account in an Ecuadorian public financial institution. The 55.5 percent of the respondents indicated that they had never heard CSR definition while 44.5 percent knew this concept.

4.2.2. Descriptive Statistics and Exploratory Factor Analysis

To extract the factors, all variables were subject to the test method of construct validity using principal components analysis while the rotation method was Oblimin, whose representing component correlation matrix reveals values higher than 0.3. Factor loading values were determined based on 0.5. Items Tru4, Eco1, Eco4, Leg1, Eth1, Eth3, and Phi3 were removed and omitted in subsequence analysis, they presented lower internal consistency and discriminant validity. Therefore, the initial number of items was 32, and we reduced them to 25 items. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) provided the correlation between measured variables and the underlying factors. In EFA, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkim (KMO) must be higher than 0.5 (KMO>0.5), and Bartlett’s test performs a significance at the 5% level or smaller (Sig. <0.05). In our study, the KMO was 0.928 and Bartlett’s sphericity test significance was 0.000. Table 3 presents descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics and exploratory factor analysis.

On a five-point Likert scale, LEG shows a composite score of 4.026, which is the highest perceived value compared to the remaining CSR initiatives (µ = 3.165–3.803). This result reflects that the Ecuadorian banks focus on CSR legal initiatives and their perception by the customers. However, respondents indicate a reduced sensitivity for PHI (µ = 3.165). Customers did not see ethical and economic responsibilities in CSR of their banks because its composite score is 3.803 and 3.537, respectively.

The LOY composite score is 3.962, showing a high level of customer’s bank loyalty. This finding is fundamentally aligned by the fact that clients believe that “they will continue doing more business with their bank in the future” (µ = 4.276), and they are identified as “loyal customers with their bank” (µ = 4.000). The composite score for QUA is 3.885, suggesting that respondents perceive high service quality in their banks. Courtesy and individualized attention are statements more agreed by clients (µ = 4.149 and µ = 3.860, respectively). The composite score for TRU is 3.825. Clients “trusted their bank” (µ = 3.912) and “trusted in the financial and service information provided by their bank” (µ = 3.825). The composite score for SAT is 3.798, which is reinforced by the satisfactory customers feeling of their bank (µ = 3.974).

4.2.3. Reliability Analysis

Cronbach’s alpha scores are between 0.715 to 0.859, which is above the recommended level of 0.6 [62]. All measures meet the suggested level of 0.7 for composite reliability ranging from 0.701 to 0.865. The average variance extracted (AVE) values fluctuate from 0.526 to 0.682, which is greater than the proposed level of 0.5. All the correlation coefficients do not exceed the value of 0.7, showing multicollinearity between variables. To assess the discriminant validity, the square root of the AVE should be larger than the correlations among the constructs in the model [63]. The diagonal entries with values in parenthesis in Table 4 represent the square root of the AVE for each construct. The other values indicate the correlation coefficient values among the constructs. All constructs show adequate discriminant validity.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

4.2.4. Regression Analysis

Table 5 shows the results of individual linear regressions to test the effect of CSR initiatives on non-financial corporate performance in the Ecuadorian banking industry. The lowest adjusted R-Square is 0.323 (H1e result), and the highest value is 0.657 (H1a result).

Table 5.

Individual regression results: Non-financial corporate performance (NFCP)—research model B.

Hypothesis 1a is accepted, showing that non-financial corporate performance is positively affected by CSR initiatives in the Ecuadorian banking industry. These findings are consistent with the customer-oriented perspective of banks and their efforts to build, maintain, and reinforce their reputation and customer relationship [28,30,31]. Furthermore, we found that economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities initiatives present an individual significant positive relationship with non-financial corporate performance in the Ecuadorian banking industry. The perception of Ecuadorian customers is that banks develop fresh financial products, employ high regulatory levels, promote corporate governance, practice ethical norms, and stimulate inclusive finance for vulnerable groups. Thus, hypotheses from H1b to H1e are accepted at the 1% level of significance. Moreover, hypotheses from 2 to 5 are accepted, indicating that the non-financial corporate performance is positively affected by customer’s band trust, customer’s brand loyalty, customer’s perception of quality, and customer satisfaction, respectively. CSR programs reduce the inherent uncertainty in bank transactions perceived by clients, who recognize CSR activities as positive brand initiatives, which provoke an increase in their repurchase intention [34]. The repeated purchasing behavior is caused when the customer is convinced of and identifies with the company’s CSR performance [35], which generates long-term corporate profitability by the word-of-mouth recommendation, decreasing the customer retention and marketing costs. Furthermore, customers recommend the company to others when their perceptions of service quality are increased by the introduction of CSR practices on a firm [17], and clients might increase their willingness to pay more for a particular product or service from a socially responsible company [43]. Prior studies indicate a direct positive correlation between CSR and customer satisfaction levels because the company’s customers are potential stakeholders [2,64,65]. CSR is one of the most important factors in the creation of a positive corporate image, including customer satisfaction, which is a necessary input of the corporate strategy.

Table 6 presents the results of the multiple linear regression using all CSR initiatives that affect the non-financial performance in the Ecuadorian banking industry. The model reflects an adjusted R-Square of 0.701. Hypotheses from H1b to H1e are accepted. Non-corporate performance is positively affected by economic (β = 0.310, p < 0.01), legal (β = 0.240, p < 0.01), ethical (β = 0.211, p < 0.01), and philanthropic (β = 0.103, p < 0.01) responsibilities initiatives. The high significance of regression coefficients suggests that customers regard economic responsibility initiatives as the transcendental determinant while the least important CSR initiative is philanthropic responsibility initiatives.

Table 6.

Multiple regression results: Non-financial corporate performance (NFCP)—research model B.

5. Conclusions

We analyzed the relationship between corporate performance and CSR initiatives in the Ecuadorian banking industry. We introduced two statistical models. The first model is for financial corporate performance, using a sample of 304 firm-year observations during the 2013–2018 period. Using both ROA and ROE as proxy for financial performance, we found that the financial corporate performance is positively affected by CSR initiatives. The positive relationship between CSR initiatives and the financial corporate performance is aligned with prior study’s findings in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Lebanon, and countries of the former Soviet Union and Central and Eastern Europe [59,60,61]. Financial intermediary’s reputation reinforces our results, given that, banks with higher CSR would own higher financial earnings and asset quality. Furthermore, CSR might be used as a primary business strategy to increase the bank’s profits by improving their image by participating in social initiatives via CSR activities. Therefore, these activities are considered in the strategic plan to increase goodwill and reduce promotional costs.

The second model includes the non-financial corporate performance as a dependent variable while CSR initiatives are considered as explanatory variables using a sample of 228 records from a self-designed online questionnaire. We found that non-financial corporate performance is positively affected by CSR initiatives. We show that economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibility initiatives in CSR have a significantly positive relationship with the non-financial corporate performance. Moreover, the non-financial corporate performance is positively affected by customer’s brand trust, customer’s brand loyalty, customer’s perception of quality, and customer satisfaction. These results are aligned with the study of Yoon et al. [34] because clients recognize CSR activities as positive brand initiatives. Customers increase their purchase intention and their willingness to pay more for a particular product or service upgrade, which is considered a necessary input of effective corporative strategy and has a direct positive effect on long-term corporate profitability.

We are able to conclude that customers of the Ecuadorian banking industry perceive banks as socially responsible entities and the Ecuadorian banks invest economic resources in CSR activities as a corporate governance policy to increase their financial and non-financial performance. We found that the Ecuadorian banks follow their CSR bottom line and build trust with consumers to increase their financial benefit. Furthermore, the perception of consumers is that the more socially responsible the bank is, the more supportive the community becomes. Especially, Ecuadorian consumers associate CSR activities with legal initiatives, because they feel that their savings are protected by the Ecuadorian banking regulations. Using our demographic analysis, we distinguished that the Ecuadorian millennials and Generation Z emphasize the importance of CSR initiatives because they show enough knowledge about CSR activities, and they mention that CSR activities begin on their own, showing their activism in CSR components. We suggest that it is urgent and necessary to invest in CSR activities because it (i) supports the development of the financial and business models for various segments, (ii) creates higher employee motivation, which increases the firm performance level, (iii) generates positive publicity by brand recognition, and (iv) offers real benefits for the society as a whole. Furthermore, our study pinpoints bank consumers’ perceptions of CSR initiatives in Ecuador. We recommend that bank executives review and adjust their business strategic plan and their corporate governance strategy according to the customer’s perceptions and needs to increase the banks’ trust and consumer satisfaction.

We propose to the Ecuadorian banking industry to (i) introduce innovation in their business process and promote 3R programs which reduce, reuse, and recycle resources, (ii) include environmentally friendly initiatives focused on energy saving by the use of electronic sources instead of physical instruments, and (iii) offer special bank’s benefits to citizens in precarious conditions, providing them specific credit linen to solve their economic problems, accompanied by the academic and financial education. CSR initiatives that focus on education programs and training show the highest effect by increasing the social benefit. Therefore, we strongly recommend bank executives to include hiring initiative as part of their socially responsible efforts, allowing hiring younger people by jump-start careers by giving them their first job. Finally, the Ecuadorian government needs to be involved in CSR regulation to improve its standards by the development of CSR legislation to control employee-firm relationships, maintain health and safety standards in workplaces, prevent discrimination, and promote equal pay. Governments are in a position to build capacities for CSR between companies, stakeholders, and consumers. In Ecuador, there is no public CSR report available for the Ecuadorian firms because companies manage their own CSR sphere. Therefore, the Ecuadorian Government needs to (i) provide guidelines of CSR report and codes of conduct, (ii) collect and analyze CSR data to improve the public policy, (iii) introduce standard-setting through the provision of CSR policy frameworks, (iv) include corporate governance indicators in the annual reports presented by companies, and (v) increase the disclosure and transparency of social responsibility practices by the regulation of monitoring and reporting. Our paper contributes to prior literature by providing two models of corporate performance using financial and non-financial variables, offering the possibility to measure the potential gaps between what customers expect and perceive toward a socially responsible bank, identifying the importance of investing in economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibility initiatives. Second, CSR initiatives in the Ecuadorian context have not been deeply analyzed. We are able to conclude that CSR activities have a strong effect on customers because CSR initiatives positively influence the client’s trust, loyalty, perception of quality, and satisfaction. Therefore, managerial plans might strategically allocate the company’s financial resources in CSR investment. Furthermore, we suggest potential sources of improvements of actual CSR strategies to fit CSR activities with customer’s ideas, desires, and needs.

The main limitation of our study is the direct access to CSR data because Ecuador does not calculate the CSR index, due to the medium degree of development of CSR activities in the Ecuadorian economic sector. For future research, the authors suggest including a variable to measure the motivation of banks to engage in CSR activities because previous studies ignore if this mechanism is strategic or altruistic. It is necessary to analyze the stage of adoption of CSR practices in the Ecuadorian context. We recommend including the corporate governance index with a CSR component and compare our results with cross-cultural investigations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.T.-P. and H.S.; methodology, A.B.T.-P., H.S. and Y.L.; software, A.B.T.-P. and H.S.; validation, A.B.T.-P. and H.S.; formal analysis, A.B.T.-P.; investigation, A.B.T.-P.; resources, A.B.T.-P., H.S., Y.L. and C.W.L.; data curation, A.B.T.-P. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.T.-P.; writing—review and editing, A.B.T.-P., H.S. and C.W.L.; visualization, A.B.T.-P.; supervision, H.S. and Y.L.; project administration, H.S. and C.W.L.; funding acquisition, H.S. and C.W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Maignan, I.; Ferrer, O. Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Kasliwal, N.; Joshi, M. Corporate social responsibility and consumer behavior: A review to establish a conceptual model. Int. J. Emerg. Res. Manag. Technol. 2017, 6, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.; Le, T.; Huynh, L. Perception of bank customers towards banking corporate social responsibility in Vietnam. Int. Res. J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 161, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, C.; Lefcovitch, A. Corporate social responsibility and banks. Amic. Curiae. 2009, 78, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Dacin, P. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Minor, D.; Wang, J.; Yu, C. A learning curve of the market: Chasing alpha of socially responsible firms. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga Yumiguano, G.E.; González, M.G.; Torres, Y.A.; Zurita, E.G.; Pinilla Rodríguez, D.E. Desarrollo financiero y crecimiento económico en el Ecuador: 2000–2017. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, C.; Govea, K.; Hurtado, G. Incidencia de la responsabilidad social empresarial en la rentabilidad económica de empresas ecuatorianas. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H. Social responsibilities of the businessmen; Harper Brother: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S. Dimensions of corporate social performance: An analytical framework. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1975, 17, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.; Kramer, M. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Melo, T.; Garrido-Morgado, A. Corporate reputation: A combination of social responsibility and industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, J. Entrepreneurs: The world needs you. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2012, 54, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.; Dunford, B.; Boss, A.; Angermerier, I. Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. J. Bus. Ethics. 2011, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, E.; Güner, S. The impact of corporate social responsibility, service quality and customer-company identification on customers. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics. 2008, 77, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.; Sen, S.; Mota, M.R.L. Consumer reactions to CSR: A Brazilian perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y. CSR and service brand: The mediating effect of brand identification and moderating effect of service quality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Park, S.; Rapert, M.; Newman, C. Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identify salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Stanaland, A.; Lwin, M.; Murphy, P. Consumer perceptions of the antecedents and consequences of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, Y. Corporate social responsibility and CEO risk-taking incentives. J. Corp. Financ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searcy, C. Corporate sustainability performance measurement systems: A review and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G. Measuring corporate sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2000, 43, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrubaiee, L. Exploring the relationship between ethical sales behavior, relationship quality, and customer loyalty. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2012, 4, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, T.; Wu, L. Customer retention and cross-buying in the banking industry: An integration of service attributes, satisfaction, and trust. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2007, 12, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Shekhar, V. Dimensional hierarchy of trustworthiness of financial service providers. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2010, 28, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matute-Vallejo, J.; Bravo, R.; Pina, J. The influence of corporate social responsibility and price fairness on customer behavior: Evidence from the financial sector. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Corporate social responsibility and bank customer satisfaction: A research agenda. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2008, 26, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S.; Sale, C. An analysis of corporate social responsibility, trust and reputation in the banking profession. In Professionals’ Perspectives of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, A. Competitive and optimal responses to signals: An analysis of efficiency and distribution. J. Econ. Theory 1974, 7, 296–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gurhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.; Massy, W.; Lodahl, T. Purchasing behavior and personal attributes. J. Advert. Res. 1969, 9, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bartol, K.; Martin, D. Management; McGraw-Hill Company: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, J.; Droge, C. Service quality, trust, specific asset investment, and expertise: Direct and indirect effects in satisfaction-loyalty framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F. The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force behind Growth, Profits, and Lasting Value; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing in the Value of a Brand Name; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Wernerfelt, B. Defensive marketing strategy by customer complaInt. management: A theoretical analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.; Basu, K. Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.; Berry, L. SERVQUAL: A multi-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.; Berry, L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.; Webb, D. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshoff, C.; Gray, B. The relationship between service quality, customer satisfaction and buying intentions in the private hospital industry. South Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2004, 35, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.-H.; Yu, J.-E.; Choi, M.-G.; Shin, J.-I. The effects of CSR on customer satisfaction and loyalty in China: The moderating role of corporate image. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Shabana, K. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.; Srinivasan, S. E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: A contingency framework. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowart, K.; Fox, G.; Wilson, A. A structural look at consumer innovativeness and self-congruence in new product purchase. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 1111–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M. Perceived value, service quality, corporate image and customer loyalty: Empirical assessment from Pakistan. Serbian J. Manag. 2012, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Soch, H. Validating antecedents of customer loyalty for Indian cell phone users. Vikalpa. 2012, 37, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, C.; Lee, S.; Babin, B. Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. Webcasting adoption: Technology fluidity, user innovativeness, and media substitution. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 2004, 48, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Endogeneity in CEO power: A survey and experiment. Investig. Anal. J. 2016, 45, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulcanaza-Prieto, A.; Koo, J.; Lee, Y. Does cost stickiness affect capital structure? Evidence from Korea. Korean J. Manag. Account. Res. 2019, 19, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecuadorian Superintendence of Banks. Managerial Report from Monthly Financial Newsletters. Available online: http://estadisticas.superbancos.gob.ec/portalestadistico/portalestudios/?page_id=415 (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Chen, E.; Dixon, W. Estimates of Parameters of a Censored Regression Sample. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1972, 67, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.W.; Shen, C.H. Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance. J. Bank Financ. 2013, 37, 3529–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalilov, K.; Vasylieva, T.; Lyeonov, S.; Lasukova, A. Corporate social responsibility and bank performance in transition countries. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2015, 13, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Khan, B.; Tariq, R. Corporate social responsibility impact on financial performance of bank’s: Evidence from Asian countries. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 618–632. [Google Scholar]

- Fayad, A.; Ayoub, R.; Ayoub, M. Causal relationship between CSR and FB in banks. Arab. Econ. Bus. J. 2017, 12, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W. The partial least squares. approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.; Kenny, D. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daub, C.; Ergenzinger, R. Enabling sustainable management through a new multi-disciplinary concept of customer satisfaction. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).