1. Introduction

School is important for children’s learning, but also for basic human rights and wellbeing. In emergency situations such as conflict, natural disasters, poverty, and large-scale migration, children’s access to quality education is limited [

1]. However, recent years have seen an increased emphasis on the provision of education in emergency settings. This is mainly due to the serious consequences of children missing out on learning. However, it is also a result of the commonly held views that education is good for children’s wellbeing and that education can mitigate the negative effects of conflicts and disasters. Education can protect children from some of the negative consequences of war and conflict. Regular schooling has long been seen as important in providing stability, structure, and routine, which will help to establish predictability and help children cope with stress [

2]. Schools are often recommended as the setting of choice for more targeted psychosocial support, as it offers contact with many children (and parents), and is a familiar and non-stigmatising setting [

1]. Studies from different settings have shown that both children and parents in emergency situations greatly value participation in education [

2,

3].

1.1. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

“Education in emergencies” has been promoted since the early 1990s, and education is now included in the humanitarian response paradigm [

4]. Education for children in emergencies refers to opportunities for structured learning for children and youth during crises or following crises. Education can involve early childhood development, primary, secondary, non-formal, technical, vocational, and higher education. Education in emergencies is believed to provide physical, psychosocial, and cognitive support and protection, which contributes to children’s healthy development. Emergencies include conflicts, situations of violence, forced displacement, disasters, and public health emergencies, which are characteristics that apply to many areas of Sudan and South Sudan. A number of studies and reports on education are available, for example, on blended learning [

5] and aspects of education and peace (especially in South Sudan) [

6,

7]. There are interesting studies on how to reach marginalized children, for example, by the use of games to provide learning opportunities for hard-to-reach children [

8].

In this study, we use the terms mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Mental health is not only the absence of symptoms or distress, but also the presence of wellbeing and the ability to cope with stressors, to be part of a community, and to be able to learn and develop. Therefore, as used here, the concept of mental health is similar to psychosocial wellbeing, which refers to the dynamic relationship between social experiences, culture, and psychological functioning [

9].

We use the term “psychosocial support” in line with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee [

10] to describe any type of intervention or support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial wellbeing or to prevent or treat mental disorders, often focusing on human capacity and an enabling environment. One type of psychosocial support is social emotional learning (SEL), which usually refers to school-based activities to strengthen children’s social and emotional skills, as well as self-management and decision-making.

The psychosocial approach, as we use it in this study, considers many aspects of functioning and wellbeing. An individual is part of a social context where the environment cannot be completely separated from the individual, as people are always influenced by, and influence, their surroundings. Children are part of a complex social, economic, and historical context. If we are to understand any aspect of children’s lives such as psychosocial wellbeing and education, this context must be considered. This emphasis on context is in line with current guidelines for psychosocial interventions. We use the framework of the “developmental niche” [

11] as a way to structure the environment in which the children live. In the niche concept, it is emphasized that children are influenced by, and exert an influence on, their niche. The wider political, geographical, and economic context will affect a child’s particular niche. The niche is divided into three parts—the settings where children live their lives, the practices that affect them, and the ideas and beliefs of their caregivers. The developmental niche framework has been used in a number of settings and has also been shown to help identify promising intervention strategies [

12]. Using this framework, we considered (1) physical and social settings, (2) childcare customs and practices, and (3) ideas and beliefs about psychosocial support and education of teachers and other adults who may influence children’s lives.

1.2. Sudan and South Sudan

The informants in this study work with children and young people in South Sudan and Sudan. Although the situations in South Sudan and Sudan are different in many respects, the circumstances are difficult in both contexts. The situation is particularly dire in South Sudan, where the civil war, which started in 2013, is still ongoing. The consequences of the war for the civilian population have been devastating, in the form of violence, human rights violations, and widespread attacks on infrastructure.

The death toll since the outbreak of the civil war in 2013 has been high. More than 1.6 million people have been internally displaced, and 215,000 are living in UN Protection of Civilians sites (OCHA, September 2017). In addition, the total number of South Sudanese refugees living in neighbouring countries such as Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, DR Congo, CAR, and Uganda is 2.1 million (OCHA, September 2017). A particular cause of concern in an educational context is that 63% of the refugees are under the age of 18, and education is insufficiently prioritized in the humanitarian response. The situation in Sudan for the refugees from South Sudan and Eritrea is also challenging, but, apart from the areas in Darfur (South Sudan), South Kordofan, and Blue Nile (Sudan), the refugee pupils living in and around Khartoum Sudan are not plagued by war like the children in South Sudan. On the other hand, refugees from South Sudan who came to Khartoum were not granted the same legal status as refugees from other places, such as Eritrea. This has led to a serious lack of protection and education for children and young people, especially for the many unaccompanied children. Moreover, unlike many of the camps, Khartoum is not within the areas that receive funding for aid activities. These factors add to vulnerabilities, and many displaced children and young people are exposed to abuse and both domestic violence and violence outside the family.

1.3. Psychosocial Consequences of Disasters and Conflict

Many pupils in both Sudan and South Sudan are faced with a diverse range of adverse experiences caused by poverty, domestic violence, abuse, neglect, and experiences of war, which are often made more complex by the interplay of all these factors. Such experiences may cause severe trauma reactions, depression, anxiety, and reduced concentration and motivation for schoolwork [

13,

14]. There is a substantial body of knowledge on the mental health and psychosocial consequences of disasters and conflict on children, including many good reviews [

15,

16]. Documented effects of loss and trauma on academic functioning are fairly strong [

17,

18]. Children in such adverse situations may react with fear, social withdrawal, a lack of concentration, sadness, depression, sleep problems, aggression, lost motivation for education, and dropping out of school. Adverse experiences and major sources of stress that affect mental health and learning among children in humanitarian situations and war have sometimes been divided into what is labelled “potentially traumatizing events” (PTEs) versus “daily stressors” [

19]. PTEs include direct exposure to war related violence, while daily stressors include social and material conditions such as lack of food, unsafe and crowded living conditions, lack of work and income, and shame and marginalization related to poverty or displacement. Another group of adversities that might be classified as both PTEs and serious daily stressors are abuse, neglect, and witnessing violence between parents or other members of the household. Several authors have pointed to the need for an integrated perspective on how all these groups of adversities cause stress and affect mental health in children and how they might interplay and mutually increase negative impact. In this study, we have this integrated perspective as a background for gathering information.

1.4. Resilience

Numerous studies have documented that people of all ages are resilient in the face of adversities [

20,

21,

22]. Current research indicates that focusing on resilience and protective factors is an important long-term goal for positive mental health and psychological functioning of refugee children. Protective factors for children include age, levels of self-esteem/efficacy, maintenance of cultural identity, social support from peers and family, a sense of belonging and safety in school and community, and innovative social care services [

23]. Studies focusing on resilience among Sudanese refugees in high-income countries highlight factors such as reliance on religious beliefs, cognitive strategies such as reframing the situation, relying on their inner resources, and focusing on future wishes and aspirations. Social support is an important resilience factor and a coping strategy [

24]. Focusing on the resilience factors of both individuals and in the community is central to understand how the impact of adversities might be reduced or overcome and will therefore also be a central focus for information gathering.

Resilience is increasingly used as a frame for understanding how people experience and cope with stress, and understanding communities’ and agencies’ potential to mitigate harmful effects of adverse situations [

25]. Thus, resilience is a description of characteristics that are associated with less psychopathology, and of the interactions and processes that help mobilize resources to support protection, coping, and recovery [

25,

26].

1.5. Education as a Means to Reduce the Negative Aspects of Aversive Factors and Lacking Resources

The United Nations in general, and UNHCR, UNICEF, and UNESCO in particular, have emphasized the necessity of education in emergencies to support sustainable development. In 2016, Education Cannot Wait was launched as the world’s first dedicated fund for education in emergencies. The fund seeks to generate greater shared political, operational, and financial commitment to fulfil the educational needs of children in emergencies, and UNICEF is currently hosting the secretariat [

27]. In the UNHCR 2030 strategy for refugee education, the focus is on how to give all children access to inclusive and equitable quality education that enables them to learn, thrive, and develop their potential [

28]. Education has increasingly been seen as a way to create physical and psychological safe spaces and to provide a sense of normalcy [

2].

Both education in itself and psychosocial support in the school context are widely used strategies to reach out to children who have been exposed to adverse experiences in areas with poor or non-existing systems for mental health services and psychosocial support. Education aims to promote both academic performance and wellbeing.

Some (although limited) research on psychosocial wellbeing and education in the context of Sudan and South Sudan has been conducted. A large-scale study of children with disabilities in Darfur found that access to school was limited for all children, whether they were disabled or not. The study found that schooling did not provide effective protection against anxiety and distress [

29]. Another study of the education of children with complex disabilities confirmed that school attendance was lacking [

30]. The study also showed efforts to develop services and concluded that the children in the project developed better social and self-acceptance. A study from Quran schools near Khartoum revealed severe health problems [

31]. Harsh discipline and physical punishment were thought to be common and are linked to a negative classroom environment. One study examined the relationships between Sudanese secondary science teachers’ pupil control ideology and their students’ perceptions of the psychosocial classroom environment. The findings revealed no significant relationship between students’ perceptions of the classroom environment and teachers’ harsh discipline practices. However, the ideology of teachers favouring harsh discipline was linked to low psychosocial support [

32].

An increasing amount of literature focuses on the importance of building interventions for traumatized populations on local culture and society [

33] and especially focus on local resources, and local ownership to secure sustainability [

34]. In an article describing what is called the “Rwanda experience,” a serious gap between biomedical MHPSS programs and local needs and reality is shown. The author concludes that mental health and psychosocial support programs are unlikely to be successful when local perceptions of suffering and healing are not sufficiently respected based on culture and society [

33].

In light of the toll of adverse life conditions on children’s education and wellbeing, it is important to investigate how children can be supported and what interventions teachers, parents, NGOs, and scientific staff think are needed and acceptable, in particular in a school setting. To minimize the negative aspects of the shortage of resources and harmful practices, there is a need for assistance and programs that build on existing resources and strengthening resilience. To achieve this, development of any intervention in schools must build on local knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding what assistance children need and what the schools can do to meet these needs. Thus, the focus of the current article is to explore stakeholders’ views on the role of school education in the psychosocial support and wellbeing of children in the context of Sudan and South Sudan.

2. Method

This is a qualitative explorative study. The data consisted of oral interviews and open-ended written questionnaires. Data were collected between February 2018 and May 2019. In Sudan, the data were collected as part of an NGO project on the relationship between psychosocial consequences of adverse experiences and children’s participation in education in LMIC. The data collection, including the interviews and group discussions, was performed by the first two authors with support from the third author, all of whom are clinical psychologists. The data collection from the South Sudanese teachers was performed by the fourth author in the context of longer-term capacity-building and cooperation.

2.1. Informants and Interviews

We used a purposive convenience sample. The informants were teachers and other stakeholders, and the majority were Sudanese or South Sudanese (see

Table 1 for an overview). Originally, the plan had been to interview a larger group of parents (both mothers and fathers) about the same issues, but, due to travel restrictions between Khartoum and the surrounding camps for refugees, this was not possible.

The pupils to whom the South Sudanese informants refer were all South Sudanese, although some were internally displaced. The pupils the informants in the North refer to were refugees or internally displaced, primarily from South Sudan or Eritrea.

The purpose of the oral interviews was explained, and participants signed a written consent for participation. No personal information was gathered from the informants, except their relationship to children in general (for example, teachers or parents). In total, interviews and discussions involved 60 people.

Before conducting interviews with teachers and parents, a group discussion was conducted with 10 university teachers and researchers at a university in Khartoum. This group had extensive contact with both the refugee population and teachers as counsellors working with refugee children, both in Khartoum and in the camps for South Sudanese outside Khartoum. The group discussion yielded information on the context and system level. It also provided opportunities for input to the research questions. Examples included: “is this issue relevant?”; “should we approach the topic differently?”; and “are there other issues we ought to investigate?” They also provided general input, for example, with regard to our preliminary observations (“if guidelines for emergency education have not been mentioned, why do you think that is so?” and “how do you describe the needs of the children in this school compared to those in the camps”?). Individual in-depth interviews were conducted with two of the counsellors.

To gain better background information, a group discussion with five NGO representatives in Khartoum was also conducted. These representatives worked with refugees from South Sudan and elsewhere in Sudan. This discussion gave information about the broader context of the teachers’, children’s, and parents’ situations with regard to cultural, economic, and political factors.

After this, 26 Eritrean teachers (24 men) at a refugee school in Khartoum were interviewed as a group. The teachers were themselves refugees living in Khartoum, teaching Eritrean refugee children. Even though these teachers have different experiences and live and work in a different context than the South Sudanese teachers, their perception and evaluation of the challenges of delivering psychosocial support to refugee children could serve as supplementary information to the information gathered by the questionnaire answered by the South Sudanese teachers. The questions in the interview were open-ended and covered the following themes:

In your experience, what are the signs that a child has problems with frightening experiences from their past? (for example, scary memories)?

What are children in your area afraid of?

What are the biggest obstacles that prevent children from attending school?

Do these experiences have any impact on them/their functioning today?

Do scary experiences affect their attention, motivation or accomplishment at school?

As a teacher, can you do anything to help the children?

Is there anything that could be done by the school as a system to help?

The questions were formulated in English by the first and second author, and translated into Arabic by a Sudanese psychologist (the third author).

Two fathers from South Sudan, who were living in a refugee camp outside Khartoum, were individually interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide addressing the following questions:

In your experience what are the signs that a child has problems with frightening experiences from their past? (for example, scary memories)?

What are children in your area afraid of?

What are the biggest obstacles that prevent children from attending school?

Do these experiences have any impact on them/their functioning today?

Do scary experiences affect their attention, motivation or accomplishment at school?

The data from the interviews were supplemented by a questionnaire that was completed by 17 South Sudanese Master’s students who were all teachers and who described their experiences of teaching children in South Sudan. The questionnaire consisted of the following questions:

To what extent have you witnessed school children experience any aversive events, and what type of events did this involve?

How/to what extent are the children distressed by these events, and how do the children react?

Have you observed any problems or troubling behaviour in the children?

How often would children attend school during one month? For what reasons were the children absent?

If you have seen distress in children, how do you think the school could help?

What can or should the teachers do?

The questionnaire and answers were in English.

The first and second authors also visited some classrooms in a school for refugees in Khartoum, which helped to understand the school setting and education context. Interviews with children could not be conducted due to ethical concerns, such as uncertainty as to whether it would be possible to obtain genuine informed consent.

2.2. Data Analysis

Interview data were transcribed, systematized, and summarized by the first author. The questionnaires from the South Sudanese teachers were computed, and open questions were systematized and condensed. Thus, the oral and written information were treated similarly and analyzed together.

We tried to identify patterns and themes by analyzing the data thematically, using a pragmatic approach emphasizing the context. The thematic analysis followed six phases in line with Braun and Clarke [

35]. These were (1) familiarizing ourselves with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) creating a narrative using extracts from the interviews with passages that illustrate the analytic narrative, although sometimes modifying the written excerpts in line with Malterud [

36] but keeping the meaning.

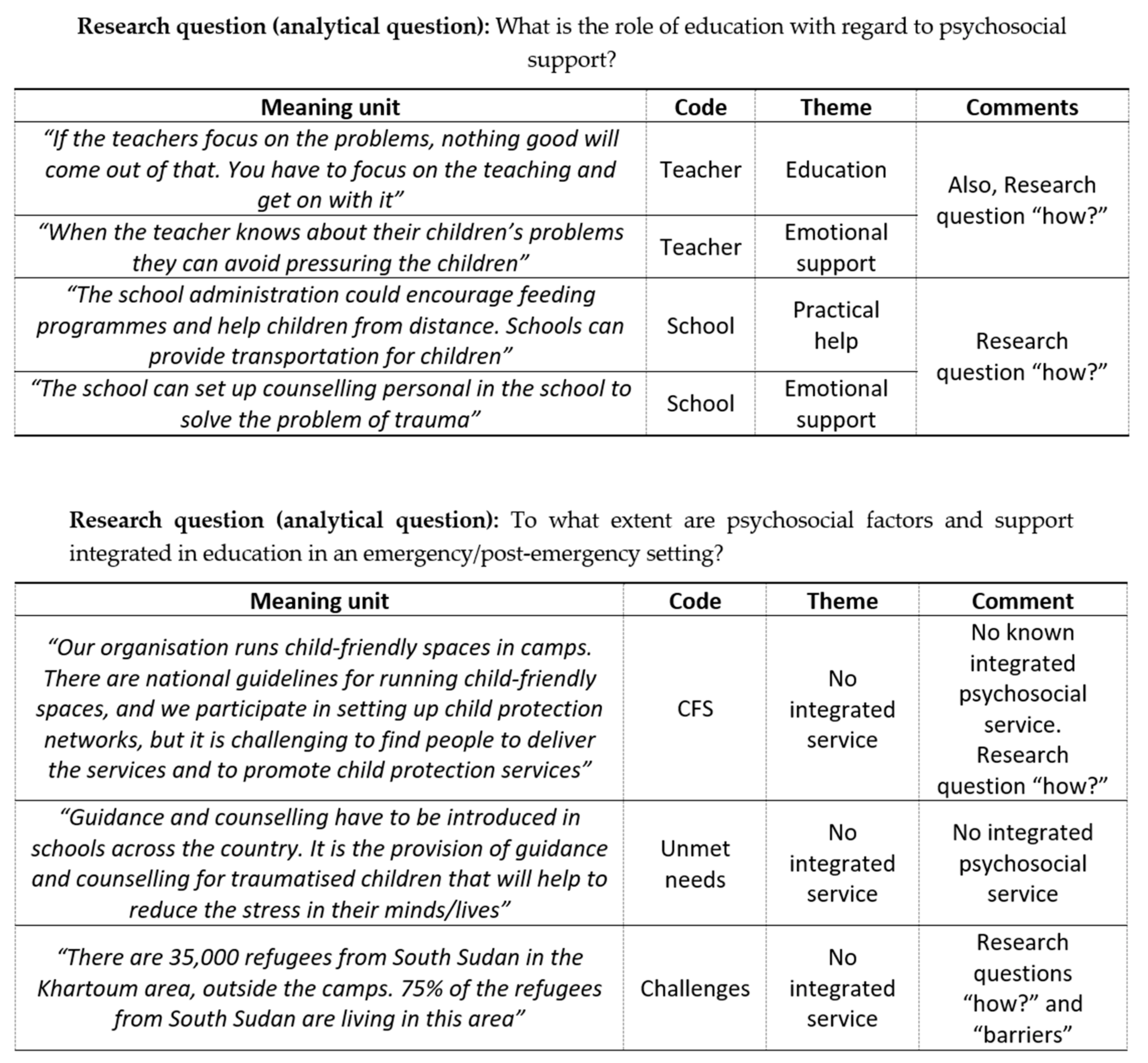

We created a coding table in which we entered statements relevant to the research question. These were found to respond to “who?” should provide support (roles), “what?” can be done (methods), and “why not?” (barriers). In addition, statements that corresponded to the theme of integrated support were coded. Thus, this question was formulated based on our initial research question—What are stakeholder’s views on the role of school education in psychosocial support and wellbeing of children in the context of Sudan and South Sudan.

In total, four questions were formulated based on the initial research questions, the questions contained in the interview guides and questionnaire, and the answers. These were:

What is the role of the school and the education sector with regard to psychosocial support?

What tools, methodologies, skills, and forms of support are/can be used to reduce the effect of aversive experiences for the children?

What are the challenges related to the delivery of psychosocial support?

To what extent are psychosocial factors and support integrated in education? Mainly, this question was answered on the basis of responses to other questions, as no informants answered this directly. Therefore, the lack of a finding is presented as a result.

The informants’ statements that responded to these questions were highlighted in order to create themes to help categorize the statements into concepts. Even after condensation, many responses could be coded and used to illustrate several themes and questions, and a comments column was therefore inserted in the coding table (see

Figure 1 for an illustration of how coding was done). Data and findings were discussed among all authors. The third author provided particular insight into the local and cultural context.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

Before the interviews, the participants were informed about the purpose of the study and how the data would be used, and they signed a written letter of consent. They were informed about the principle of anonymity and of their right to withdraw from the study at any point in the process. In terms of the written interview, a letter of information was provided, and submission of the completed (anonymous) questionnaire was regarded as willingness to take part in the study. No personal data were recorded or stored, with the exception of their age, gender, and role regarding children.

The study did, however, face ethical challenges. The interview setting did not allow complete anonymity; in the interviews, local university staff served as interpreters, and their presence could have affected the answers given in some unknown way. The university staff were researchers and counsellors who would be able to detect if anyone found participation unpleasant and offer advice on how to provide support, although this did not prove necessary. Respondents were not paid for their participation, but it could be that some kind of expectation of help may have affected the answers. On the other hand, when comparing the information given with results from other literature from the same and comparable areas, the results did not seem to be influenced by the interpreters. Because of the practical situation, it was not possible to go back to any of the participants to have them review the results and correct any misunderstandings.

3. Results

Overall, the informants recognized that psychosocial needs constitute significant challenges for children and families and that the challenges seriously impact education, including children dropping out of school. The most prominent themes were related to the lack of resources, to material challenges, and to possible ways of providing psychosocial intervention, both from the school and the individual teacher. In general, there were no clear differences between the respondents from Sudan and South Sudan, although the teachers from South Sudan mentioned hunger and food to a greater extent than the respondents from the North.

The similarity between the responses of the teachers from Sudan who took part in the group discussion and of the South Sudanese teachers’ responses to the questionnaire was striking. In general, both groups had the same focus regarding the role of the school and the education sector regarding psychosocial support, the tools that could be used, and the main challenges facing the provision of psychosocial support.

3.1. Lack of Resources

All our informants emphasized the lack of resources representing the main challenge:

“There is a large problem with the funding of education in emergencies, which has resulted in a large number of semi-permanent classrooms that need renovation. There is a generation of children growing up without education, and they need rehabilitation and or education.”

(NGO staff member, Khartoum)

Some of the teachers mentioned a general lack of resources (in the form of low payment and other demanding working conditions) as being an obstacle to the delivery of psychosocial support to the children.

One of the resources that was said to be lacking, especially by university staff and NGO representatives, was human resources. The representatives from the NGOs said that they did not have the staff to take care of traumatized children, and they pointed to a need for capacity building. Although they had started up child-friendly spaces [

37,

38], these should be supplied with treatment/care facilities to which the children could be referred. The following quote from an NGO representative demonstrates this:

“Youths who come directly from war-affected areas need some kind of assistance. How could those who meet the youths be able to help them with their trauma reactions without training?”

Representatives from the NGOs also described the education situation for refugees in Sudan as being very demanding due to recruitment problems, a lack of continuity among teachers, and inadequate training:

“There is a problem with how to recruit teachers. Currently, community volunteers are trained for four days and then sent out to work as teachers. They are often in service for one year and then they go back—when they go back, they leave a vacancy, so education in emergencies is particularly suffering, in terms of both quality and quantity. A small percentage of Sudan’s national budget is spent on education, 6%.”

Neither parents nor teachers mentioned any form of systematic delivery of psychosocial support in or outside the schools, or any expectation of this. For many children living in camps, there is no accessible school at all.

None of the NGO informants in this study had information on any integrated NGO systematic or evidence-based psychosocial support in education. One NGO had developed child-friendly spaces (CFSs), which they explained are now run by local child welfare councils. There are national guidelines for running child friendly spaces (CFSs). When starting up a CFS, the informants explained that the NGO is also participating in setting up child protection networks but that “the organization finds it challenging to find people to deliver the services and to promote child protection services” (NGO staff, Khartoum).

3.2. Attitudes and Knowledge

Several of our informants described traditional attitudes toward children (particularly girls) and education as being one of the main obstacles to school participation and a reason for high drop-out rates from school, in addition to the general lack of material resources. Teachers, representatives of NGOs, and university staff all mentioned the provision of information to, and education of, the parents as being a strategy to overcome this. Several teachers and representatives of the NGOs pointed to the lack of awareness (which they saw as being linked to these issues) not being prioritized at institutional or governmental levels. The teachers’ awareness of the relationship between adversity and the capacity to learn seemed varied, but several teachers pointed to the relationship and the need for new skills and the development of methods and routines to enable the school to help children recover.

3.3. Poor Management and Lack of Integration of Information and Knowledge between Different Services and Sectors

Some of the informants from the NGO pointed out the need for coordination and the integration of psychosocial information and capacity-building into other services, such as increasing community awareness and general education. The informants from the trauma-counselling service stressed the need for a strategy for approaching mental health issues with a focus on how to integrate mental health services in primary healthcare, but did not mention the education sector.

“The lack of coordination and integration between mental health/psychosocial services and other sectors, such as education and nutrition, is a barrier for delivery.”

(Member of academic staff, local university.)

3.4. What is Done in the School Setting to Minimize the Negative Aspects of Lacking Resources and Negative Customs?

Nearly all informants acknowledged some role of the education sector, and often mentioned personal experiences: “I had a student who first lost his father and then his mother. He dropped out of school, and we helped him to get back.”

The roles of the education sector in general, the school, and the teacher were all mentioned. One NGO representative also briefly mentioned the government (NGO representative, Khartoum). However, nobody mentioned that school can provide psychosocial support by being a safe place, providing structure, teaching life skills or through social support. Positive practices to support children’s psychosocial wellbeing were often said to include provision for material and physical needs, such as food.

There were numerous views on the role of the teacher. Some argued that these issues were not within the mandate of the teacher, whose only role was to teach the subjects: “If you focus on the problems, nothing good will come out of that. You have to focus on the teaching and get on with it” (Teacher, South Sudan). However, many teachers said that teachers could provide help with practical issues: “The cheapest things get difficult, create a lot of problems – sometimes (they) cannot afford breakfast, sometimes we give the children this” (teacher, Khartoum).

Some of the teachers also mentioned the need for special practical help for girls during menstruation: “In the case of menstruation, there are girls who find this distressing and always decide to remain at home. But teachers who teach them encourage them to regularly come to school by providing them with scraps, towels, perfumes, and washing soaps” (teacher, South Sudan; teacher, Khartoum).

A number of informants explicitly referred to how teachers can help with emotional and social issues and offer psychosocial support, for example saying that it is “important to give hope” and “when the teachers know about their children’s problems, they can avoid pressuring the children” (teacher, South Sudan; teacher, Khartoum). The need for material resources was frequently pointed to and was described as being so severe that some of the teachers had chosen to try to cover some of these needs by their own means (giving children food, buying school supplies, etc.).

3.5. What Tools, Methodologies, Skills, and Forms of Support are/can be Used?

On the topic of how to support children (i.e., what methods and tools are useful and relevant), a wide range of ways were mentioned that could take place in school, homes, health centers, policy-making institutions or aid agencies. These overlap with the question concerning the role of schools and teachers. The teachers pointed out four grouped forms of intervention that could be developed to help children who are traumatized or distressed by their current situation:

Direct support in the form of material and practical help;

Psychosocial help in the form of counselling and guidance;

Cooperating with, informing and motivating parents;

Information and advocacy to school leaders and other authorities.

Both teachers and parents stressed the urgent need to cover basic needs, such as food, water, clothes, and school supplies. Some of the teachers stressed that they ought to talk to troubled children and comfort them, besides helping them with practical needs, “such as giving them food and writing paper.” Several teachers suggested that the teachers should give direct support in the form of material help to the children, such as providing school materials, transportation to school and school meals: “The school administration could encourage feeding programs and help children from distance. Schools can provide transportation for children, and the school can set up counselling personnel in the school to tackle the problem of trauma” (teacher, South Sudan).

Some respondents saw the school as having an important role in psychosocial support by incorporating knowledge on child-friendly practice: “The school administration should act responsibly, and give the child time to act on what is required of them. Abuse such as corporal punishment, harassment, and violence must be stopped” (teacher South Sudan).

Some respondents said that psychological and emotional support would be useful, but that this should also often be linked to material resources: “The school must talk to distressed children, motivate them to explore their emotions and the difficulties facing them. The school must try to solve some of these problems, and counselling is another solution. Support them with materials as well, and the schools must provide them with food” (teacher, South Sudan).

However, some of the teachers and staff from the counselling center explicitly mentioned emotional and trauma-focused support, such as this statement by a teacher from Sudan: “Schools can help by providing psychosocial support to the learners since most of the learners are traumatized by war” (teacher, South Sudan). A similar statement was given by a teacher from South Sudan, who talked about how teachers could be trained to deliver support to children after adverse experiences in the school: “The most recognized ways of helping the war-traumatized child is through manuals for teachers—giving teachers training in child psychology … is the best way to reach war-traumatized children.”

Similarly, counselling was suggested by a few respondents as a tool for helping children who are traumatized: “Guidance and counselling have to be introduced in schools across the country. It is the provision of guidance and counselling for traumatized children that will help to reduce the stress in their minds/lives” (teacher, South Sudan).

It was suggested that teachers and school authorities should try to communicate with parents and give the parents information about the importance of schooling for the children’s future. For example, “The school should call a parent meeting in order to see what to do.” Supporting children by means of parental-school cooperation is also illustrated by this statement by a South Sudanese teacher: “The teachers need to follow up on the children and talk to the parents about cases of the children’s absence from school” (teacher, South Sudan).

Another teacher also mentioned parents and linked this statement to material conditions: “The school should involve parents to play a role at home by providing at least basic requirements for the children in the case of school fees and other requirements.”

Some mentioned that children of both sexes tend to drop out of school because their parents do not see the advantage of education, illustrating both the importance of the families and how the parents perceive the relevance of school. This was pointed out by one teacher: “A focus on life skills would possibly increase the probability of people sending their children to school. In Sudan, there are seven million children of school age; 3.5 million of these children drop out, without completing, and most of these are girls.” A broad perspective was also reflected in the following statement: “Interventions should be developed based on community outreach, mouth-to-mouth information, the creation of community involvement for schools, increasing the parents’ support for education, and focusing on girls’ education, and teacher education creates teacher stability” (local NGO representative in Khartoum).

Academic university staff recommended an approach based on close cooperation with the local communities and a focus on community-directed programs. They described the development of a program where they conduct a survey every five years so that the communities can tell them what they need. The university staff expressed a need for interdisciplinary approaches. When it comes to education, it needs to be community-based. One key question is what can be done to contribute to the implementation of knowledge in the communities.

Several of the informants pointed out that there was a need for information about psychosocial factors, such as reactions to potential traumatic experiences, psychosocial development, and how to provide psychosocial support among the general population.

Although there was no information about psychosocial support being organized in a way that was integrated with education, information from a center providing psychosocial support outside school did involve several sectors. They described the use of a questionnaire developed by the World Health Organizaion (WHO) to map health services. They also described “fact-finding missions” to find out what mental health services are available in a particular area and stated that there is a need to link mental health issues to other programs such as reproductive programs in order to avoid the stigma connected with mental health issues. They also talked about cooperation with religious leaders and other community leaders. The center where the service providers worked offered a stepwise care intervention model in four steps. The basic level (level 1) focuses on basic services, providing activities that aim to combine economic empowerment and self-esteem, such as handicraft training. Services on this level also include psychological first aid. Level 2 focuses on delivering basic mental and emotional healthcare, such as by strengthening community and family support. Level 3 focuses on building up a platform of non-specialist to deliver low threshold services to larger groups of people in affected areas, such as refugee camps and villages. Level 4 consists of specialized services provided by experts at the university center. On this level, the focus is on therapeutic methods, such as Narrative Exposure Therapy for Children (NETC) and for adults (NET).

4. Discussion

The main findings of this study are that teachers and other stakeholders in both Sudan and South Sudan express that children need support for the psychosocial challenges they experience, which are caused by a broad array of adverse experiences. Even though the information was gathered from different groups of teachers, living and working in different contexts (Eritrean refugees in Khartoum and South Sudanese children, living in camps outside Khartoum, and children in conflict-ridden South Sudan), the experiences they describe and their evaluation of the children’s situations are strikingly similar. This may be counterintuitive and could be interpreted in several ways: it could be that the circumstances and challenges described are common to several refugee groups and are relevant to the delivery of education and psychosocial support in several similar settings, but it could also be that the information-gathering in this small project was not detailed enough to show the differences between the contexts.

The experiences described are closely linked to, and caused by, the failure to meet basic physical needs, such as food, necessary equipment, and enough money to be able to travel and pay school fees. It also seems to be a widespread belief that, although teachers cannot solve this situation, the school can provide significant psychosocial support in many ways. The division of responsibility between parents, teachers and local authorities (whose role it should be) is less clear.

Although the teachers’ (and fathers’) emphasis was on the need for material and practical help, emotional and social factors were also recognized. Both barriers and solutions were focused on material help and, to some extent, human resources. This is in line with much recent research indicating that current challenges, including poverty [

39,

40] play a tremendous role in wellbeing and mental health.

It can be speculated that the respondents emphasized material needs because they thought this is what was expected. The interviewers were white foreigners, and it is possible that stereotypes about lack of resources influences the answers. However, it is also possible that material needs constitute daily stresses that are as important as traumatic stresses and in some ways outweigh traumatic stresses. This would be in line with findings from other settings, and may illustrate the need to consider both traumatic stress and daily stress and how these interact and influence each other [

39].

In our study, no one seemed to think that a systematic approach to psychosocial support exists. The findings in this study did not indicate that stakeholders believe psychosocial factors and support are integrated in education for refugee children in Sudan/South Sudan in any systematic way. Again, this may be counterintuitive, but it may be linked to the finding that, perhaps surprisingly, education and school in itself (for example, by providing structure and life skills) were not mentioned as a psychosocial support mechanism. However, it is possible that this view was taken for granted. Another interpretation is that learning and education are not considered important in promoting psychosocial wellbeing, or that they do not have sufficient positive effects on psychosocial wellbeing to be included as an intervention.

The results indicated that the teachers often (but not always) wanted to provide psychosocial support. Based on other research, it is likely that teachers’ behaviour, values, skills, and interpersonal capacities can have an important impact [

32]. There seems to be concern for vulnerable children, and several teachers expressed an understanding of the interplay between aversive, potentially traumatising experiences and participation and attendance in education. However, we were not able to find much evidence in the literature for the role of teachers for promoting wellbeing. This is surprising considering the importance attached to this issue in high-income countries. Therefore, it is likely that teachers can (but do not necessarily) foster psychosocial wellbeing in children, but the way in which they interact with the children and how they work is important. Therefore, training, support, and follow-up of teachers seems to be an important issue to prioritize.

Some of the respondents expressed a gender perspective. In general, girls have often been reported to be more severely affected than boys with regard to formal education in and after emergencies [

3], and the reported need for teachers to provide sanitary resources so that the girls can attend school during menstruation is in accordance with other similar case studies [

2].

There was no mention of disabled children, which is in line with the general lack of attention to disability in emergencies. Other studies have found that disabled children are at particular risk of abuse and neglect. In addition, children with disabilities, whether in emergencies or not, are marginalized in general education in Sudan and South Sudan, and being refugees or displaced increases their vulnerability [

29].

4.1. How can Psychosocial Support be Integrated in Emergency Education?

A common framework for psychosocial interventions in emergencies (presented by the Psychosocial Working Group [

41]) emphasizes human capacity, social ecology, culture, and values, but these must be seen in the context of environmental, physical, and economic resources. In the sociocultural context of this study in the Sudan and South Sudan, the challenges are enormous. What opportunities for strengthening an integrated approach for refugee children can be found based on this study?

Using the developmental niche framework [

11,

42] to help structure the context, we considered the results of the study in terms of agents and roles (“who?”), the barriers and challenges (“why not?”), and the suggested methods and interventions (“what?”). The niche divides the context into 1) physical and social settings, 2) childcare customs and practices, and 3) ideas and beliefs. All three components of the niche can provide opportunities for interventions. The settings that were mentioned by the respondents include school, homes, health centres, policy-making institutions, and aid agencies, and all seem possible areas for intervention. A simple type of intervention would be to use these settings for information and communication. By viewing these settings as part of the children’s contexts, messages could be better coordinated and shared. In addition, the niche itself exists in a wider historical and political context. For example, among our informants, there was no mention of lack of political will or lack of knowledge about the value of integrated psychosocial support. Neither was corruption mentioned. This may be explained by shortcomings in the research design, but it is also possible that the respondents did not perceive the link as being important. Another explanation could be that the respondents feared the consequences if they criticized the authorities. In fact, reaching out to vulnerable groups has been said to be a security issue, and critics have argued that there is a lack of political commitment to general education and emergency situations that is linked to corruption.

The multi-tiered care described by Jordans and colleagues [

43] consisted of a package with a variety of interventions. This approach seems consistent with the approach that we found in the trauma center at one of the universities in the region. This approach is based on the IASC model addressing different levels and phases for interventions, from basic needs to specialized services. Our findings can indicate that there is considerable potential for integrating psychosocial consideration into basic services, but that this would require paying attention both to knowledge and ideas as well as to practices and customs. Multi-tiered and integrated programming seems promising and also useful in order to integrate education and health, but quality studies are needed to better investigate how to implement these.

4.2. Physical and Social Settings

It is interesting that so many different physical and social settings were mentioned. Seeing these settings as part of a whole provides opportunities. Increased cooperation between schools and families, and between education and health, is likely to yield better results and is likely to be acceptable, based on the findings in this study.

The physical settings for integrating social support in education in Sudan and South Sudan are very demanding, particularly in South Sudan where the civil war is still ongoing. The constant lack of resources—material, human, and knowledge—dominate the settings that we studied. This was illustrated by the findings on introducing child-friendly places, where human resources were a challenge. CFSs were presented as a psychosocial initiative, although other studies have found limited evidence for the effects of CFSs [

37,

38].

When basic needs such as food and safety are not met, these become severe aversive factors that are likely to negatively affect mental health. Therefore, the way in which psychosocial efforts should be linked to material and physical conditions needs to be carefully considered. Both the views of some of the informants and the findings from other contexts [

22] lend support to the integration of psychosocial support into other services.

Many of the teachers had themselves endured hardship, including war experiences and being refugees. Strategies to support teachers’ living conditions and psychosocial wellbeing could also strengthen their capacity to support the children, although this would be very difficult to implement in the current war-torn situation in South Sudan. However, using a resilience frame, social and physical settings are also resources that can be identified and utilized to support recovery and coping [

26].

Similarly, the social settings were described as lacking human resources, in terms of educated teachers, and lacking continuity among the teaching staff. Therefore, increased knowledge, both of the consequences of adverse experiences for learning and how reactions to such experiences could be reduced and moderated by strategies in the schools, may have good effects.

Boniface and colleagues describe a program in South Sudan that uses a public health framework, targeting different levels (individual, family and community), and includes both prevention and treatment. Despite the challenges, they conclude that it is possible to implement MHPSS activities in a resource-poor, post-conflict setting through a community-based approach in which relief, rehabilitation, and development are complementary [

44].

4.3. Childcare Customs and Practices

Positive practices to support children’s psychosocial wellbeing were often said to include provision for material and physical needs, such as food. Therefore, using health and food-related situations to promote psychosocial wellbeing may be a useful strategy. These could be related to fostering community and social support through communal meals or knowledge about ways to promote mental health related to learning life skills.

Harmful practices in the schools, such as corporal punishment and other forms of violence directed toward the pupils, were mentioned by a few respondents, as was domestic violence. In the literature, harmful practices in school are rarely studied, whilst awareness and knowledge are part of most psychosocial intervention strategies. Although empirical evidence about the contribution of experienced organized violence to the cycle of violence is somewhat mixed [

45], war trauma and difficult living conditions are risk factors. A review by Stark and Landis [

46] found alarming prevalence rates of domestic violence in many conflict-affected settings. Some of the teachers stressed the importance of a non-violent teaching strategy and that violence against children in school should stop. It is likely that teachers’ positive skills could enhance self-confidence and reduce trauma symptoms [

47]. Similarly, teachers’ use of violence and abuse is likely to have a negative impact on both health and education. Training teachers in a non-violent code of conduct and teaching alternative ways to control classrooms may have positive effects, but we were not able to find evidence that this has been done. Educating teachers to be able to recognize children’s grief and trauma reactions, as well as techniques to reduce symptoms, may be effective, but we were not able to find evidence that this has been done in any systematic way.

Studies in numerous settings have confirmed that corporal punishment is common [

48,

49]. In this study, both teachers and other professionals expressed that they were aware of this. However, there seems to be a need for a general preventive approach to reduce violence against children at home as well as in schools. Violence in the home and classroom, whether called discipline or abuse, is a widespread problem and has serious consequences. Experiences from Uganda concerning the Good School Toolkit appear to have reduced the risk of violence by teachers on students [

50,

51], and this may be a useful approach in Sudan and South Sudan. Several studies suggest that parenting programs have the potential to both prevent and reduce the risk of child maltreatment. However, there is a lack of good evidence from LMICs where the risk of child maltreatment is greatest [

52]. Raising awareness among teachers and community leaders on the harmful effect of child abuse, and giving them tools to use in informing parents and other family members of the same, could be a strategy well worth developing.

A current approach [

40] emphasizes a broader understanding of how adverse circumstances affect children, including risk and protective factors at an individual, family, and societal level and over time (war exposure, violence, malnutrition, ongoing daily stressors, etc.), which may fit our findings from Sudan and South Sudan well. It is often stated that interventions that do not take local norms and customs into account may be inadvertently harmful, and too much focus on trauma may overlook the important role of post-conflict stressors on mental health [

4,

52].

4.4. Stakeholders’ Ideas and Beliefs Concerning the Understanding of, and Responses to, Children’s Wellbeing

The need for more knowledge of how to deliver support is mentioned by many of the respondents. Awareness and attitudes were also frequently pointed to.

Attitudes toward childrearing and childcare will also affect teachers’ attitudes concerning interaction with the children at school and which disciplining strategies to use. A better understanding of this would also be an important starting point to develop awareness-raising and knowledge-building strategies aimed at teachers, which would fit with many psychosocial programs that often have psychoeducation as an element. There are examples of smaller programs in the region that are aimed at increasing local teachers’ knowledge and skills regarding traumatized children [

53,

54]. Although evidence of the effects is needed, informants’ impressions were that the results were promising for teachers’ perceptions, understanding, and actions toward traumatized children. For example, orchestrating awareness-raising in a way that would raise the awareness of psychosocial factors among leadership, schools, and families should make cooperation easier.

There were some indications in the study that traditions, customs, and beliefs may cause girls to leave school early. It was explained that girls can be married at the age of 13, and, as married girls are not allowed to attend class with unmarried girls, they then have to stay away from school. This is an example of how a combination of material settings, customs, and beliefs can create barriers to girls’ participation in school in both the short and long term.

There is limited information about the extent to which teachers are able to recognize psychosocial problems and offer adequate support. It is likely that teachers need to be trained to recognize the impact of stressors on children, and to learn how to provide psychological support [

2,

55]. Examples of such training and awareness-raising of teachers exist, including positive results [

55], but the evidence is not robust. There is a debate about whether psychosocial needs should be addressed through psychosocial modules for teachers, or whether they are better addressed through the integration of psychosocial concepts into standard pedagogy, lesson planning, and classroom management [

56].

There is a need for more information about parents’ ideas and beliefs concerning the understanding of, and responses to, children’s wellbeing. It would be interesting to compare this to the ideas of teachers and other professionals. The current study lacks even exploratory information on this point, even though the two fathers did provide rich information that seemed to strongly support the views of the teachers. Considering our very limited base of information, this is not done in any systematic way. It is possible that parents value education so highly that they are willing to compromize on children’s safety.

5. Conclusions

Although it is often stated that education provides protection, and in itself promotes psychosocial healing and wellbeing, there is a need for more concrete evidence as to how this should be performed in a given context. This study suggests that stakeholders recognize a need for psychosocial support, but that this is closely linked to material resources. The perhaps counterintuitive findings on the lack of the role of the school in providing psychosocial support may, in itself, be a useful issue to explore further; integrated psychosocial support may be possible by considering various aspects of the context, including settings, ideas, and practices. Our findings can be interpreted as supporting the value of this multi-tiered approach—in particular relating to the links between ideas, settings, and practices. Although the challenge of basic needs and resources remains, considering possibilities in each of the three elements of the niche and at all levels of the multi-tiers may provide opportunities for low-cost interventions, such as greater user involvement. They can also be cost-efficient because the training of teachers in psychosocial support, with due consideration to both beliefs and practice, is likely to be more effective and reach many children.

Any intervention should take into consideration children’s, parents’, and teachers’ perceptions of their situation. Interventions should also be built on a knowledge of the interplay between traumatic experiences, aversive living conditions, and psychosocial support in schools. A first step should be the gathering and systematisation of this information.

As all interventions in this area will be challenged by the enormous lack of material and human resources (and, in the case of South Sudan, the ongoing civil war), an understanding of psychosocial factors, of how to prevent lasting psychosocial problems, and of how to reduce them should be integrated in all steps and at all levels of humanitarian help.