1. Introduction

Internationalization of higher education is receiving widespread attention. Student mobility across the world is expanding and universities are keen on creating learning environments that can attract a diverse student body. A recent survey of higher education institutions from 126 countries conducted by the International Association of Universities show that the majority of institutions place a high level of importance on internationalization of their institutions [

1]. The growing demand for offering courses in English in non-English speaking countries seems to reflect this phenomenon [

2]. The learning environment created by universities in South Korea also sets an expectation that college students graduating with an undergraduate degree from a university be equipped with proficient English language skills. As a graduation requirement, students must earn a passing score on a standardized test of English (e.g., IELTS, TOEIC, TOEFL, etc.), and taking courses offered exclusively in English language is common at most Korean universities [

3]. To be sure, emphasis on English language and offering courses through the medium of English is confirmed through faculty recruiting as well. English language skill is not only a requirement for the students but also for the faculty members who are often encouraged, or sometimes required, to teach various content areas in English including science and engineering [

4,

5].

Adopting English as a medium of instruction (EMI) in non-English speaking countries can serve two purposes. First, students may indeed see improvement in their English language skill, which is often critical for landing a job at a global company; with their foreign language skills, some students may even seek careers abroad. Second, it lends support to the globalization initiatives of the local universities, opening up opportunities to compete with universities across the globe and recruit international students. Furthermore, offering courses in English can attract exchange students who lack language proficiency to consider local institutions and, consequently, increase international student enrollment for local universities. Other external factors that sway universities in Korea to adopt EMI include the Korean government incentivizing universities for offering courses taught in English and university ranking reports using the percentage of courses offered in English as one measure of quality of education.

Using EMI certainly has its merits from both students’ and institutional perspectives. However, adopting EMI means that students end up learning their major subject areas in, what is for most of them, their second language. The challenge is that students attend universities for reasons other than to merely improve their English as a second language—the vast majority of the students attend universities to earn a degree and develop content expertise in a discipline of their choice. In which case, EMI may be seen as a source of discouragement to the students who are not fluent in English or lack confidence in their language skills [

5]. Students may develop a perception that they are at a disadvantage by not being able to fully grasp the knowledge and gain skills in their major area simply because of the language barrier [

3]. Therefore, to reap the benefits of EMI and minimize the downsides, it is important to examine and develop effective teaching practices to assist students’ learning of the course materials taught in English for non-English majors and non-native speakers of English.

In a classroom, students can engage with the instructor in several ways. Non-verbal engagement includes the use of body language to express their attitude, approval, and/or understanding of the course materials. More active engagements include asking questions, answering questions, and making comments during class discussions. Educators often share that Asian students in general are not enthusiastic about the latter type of engagement [

4,

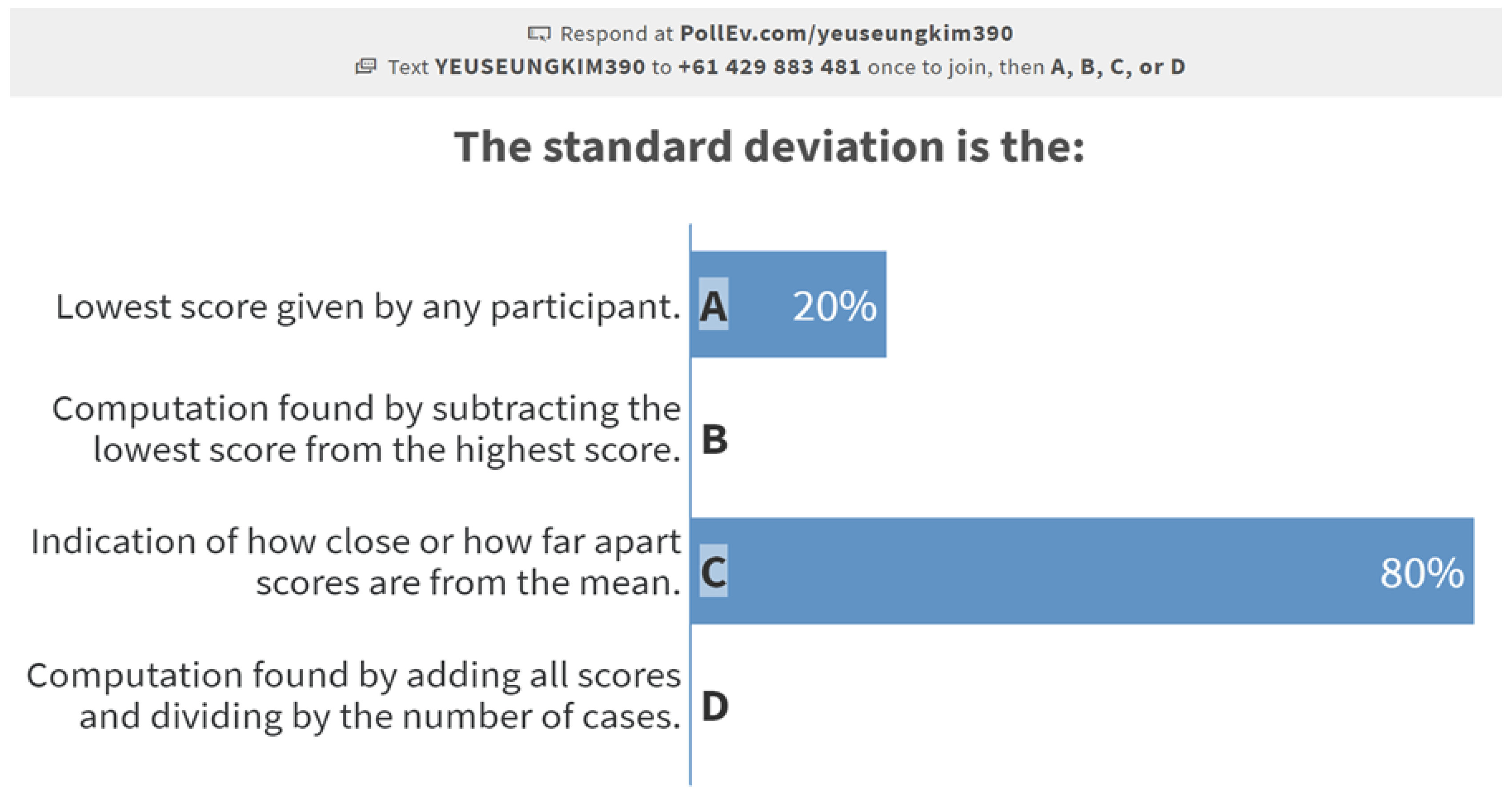

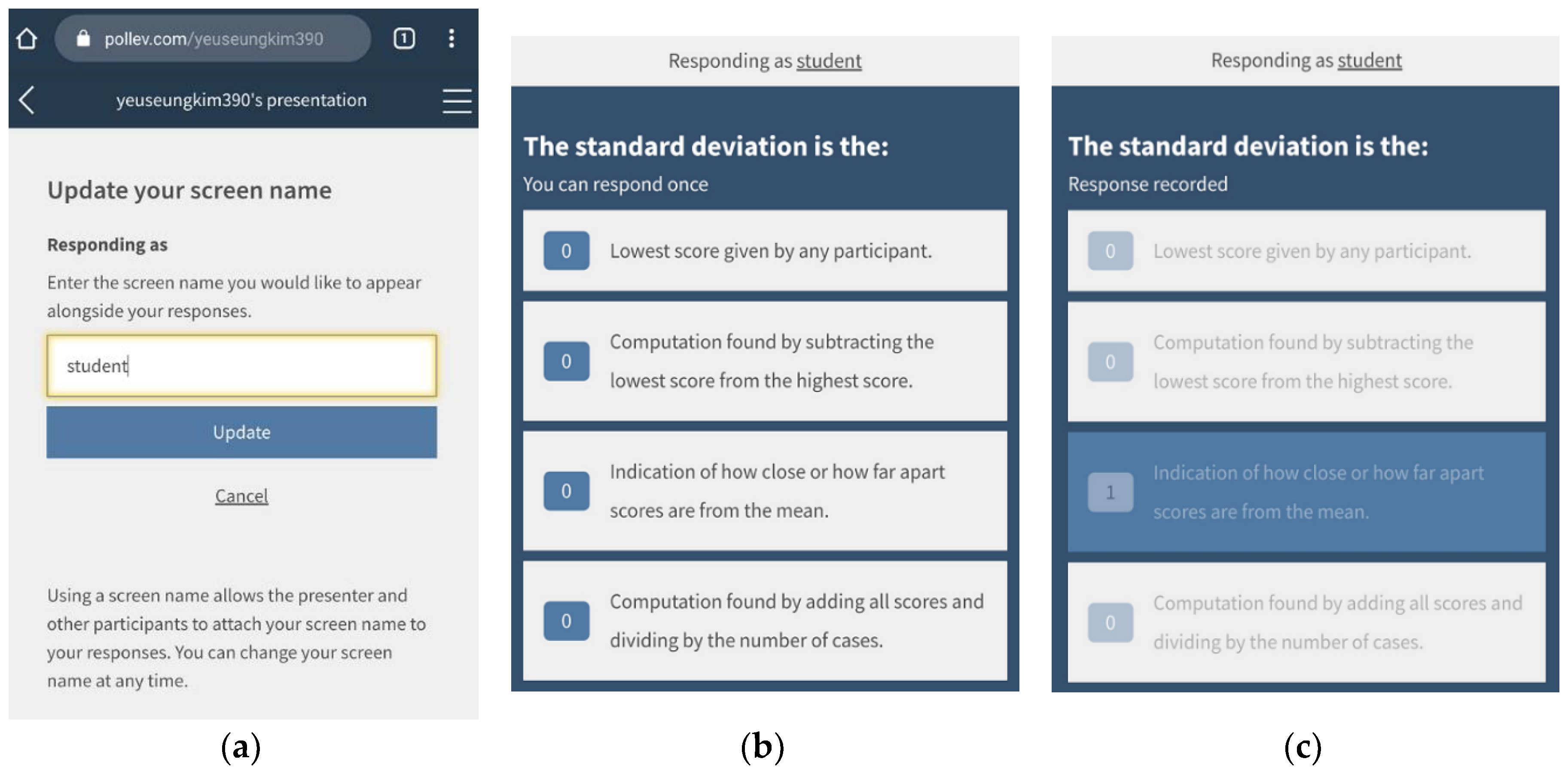

6], and EMI can further discourage the already reluctant students. As a potential solution to this problem, this study employed an interactive polling tool called “Poll Everywhere” and asked the students to use mobile devices as an active learning tool.

Active learning is “any instructional method that engages students in the learning process” [

7] (p. 223) and usually involves student activity and participation. Studies have shown that active learning techniques can improve student engagement, attitude, recall and retention of information, thinking and writing skills, and academic achievement [

7]. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the pedagogical value of using “Poll Everywhere” to foster an engaging learning environment when using EMI with non-native speaking students and make use of mobile technology to improve student experience. The results of this study will provide insight into how facilitating courses taught in English in non-English speaking countries can be improved to create a sustainable learning environment. In addition, the results can be applied to better assist the growing population of international students in English speaking countries who use English as their second language.

1.1. English as Medium of Instruction (EMI)

EMI is defined as the use of English as an instructional language in which an academic subject is taught in non-language academic subject and non-Anglophone contexts [

8]. In their investigation of the effect of EMI in Hong Kong, Marsh and colleagues [

9] evaluated the academic accomplishment of Chinese high school students. The results showed that students were disadvantaged by EMI in areas such as geography, history, and science in comparison to math. Not surprisingly, students who have better English skills are less negatively affected by EMI [

9]. In a study with Korean engineering students, students expressed that they were not satisfied with EMI and felt it interfered with their academic achievement. Despite the negative, the majority of them still supported the school policy as there are benefits such as improvement in English and the opportunities it opens up for further studies abroad [

5]. This suggests that students are not entirely content with EMI but there is some agreement that EMI can enhance their language skills in the long run. Similarly, a review of 83 EMI studies in higher education concluded that research to date does not provide sufficient evidence to conclude whether EMI is beneficial or detrimental to content learning [

2].

1.2. Student Engagement and Audience Response System

In a survey of 1857 Korean college students, when asked how often students respond to instructors’ questions, about 41.1% of the students answered favorably, and when asked how often they ask questions in class, 26.9% provided favorable answers [

10]. One potential reason for this low level of engagement is that students from Asian cultures are brought up to pay respect to teachers as experts of knowledge and, thus, have tendencies to passively accept teachers’ words. Raising opposing views or voicing dissent can be viewed as a sign of disrespect. A study has shown that college students in Korea and the U.S. favor different learnings strategies—compared to the students in the U.S., Korean students preferred sitting in the front of the classroom, taking word-by-word notes [

11]. Another potential explanation is that students are generally shy and afraid of making mistakes in public [

6]. A large class size adds to the anxiety of making mistakes in public, and on top of that, speaking in a foreign language to share their views on an academic subject matter further heightens the anxiety.

Even if students are willing to engage with the instructor and speak up during class, it is sometimes not feasible for the instructors to collect student responses in large lecture classes. One method often used to collect a large number of responses in a relatively short period of time is polling [

12]. While hand-raising is a simple, technology-free method, instructors can use devices such as a “clicker,” a hand-held device used to collect and display students’ responses to questions, or students’ own mobile device can be used to serve the same purpose.

Clickers have been useful when students did not possess their own portable devices such as smartphones, tablets, or laptops [

13]. In current classrooms, college students are most likely in possession of at least one, if not all, of these devices. Therefore, instructors are naturally leaning toward “Bring Your Own Device (BYOD)” [

14,

15,

16] for the students to participate in some form of in-class activities. “Poll Everywhere” is a web-based platform with capabilities akin to clickers while allowing the use of the students’ own devices to respond. The biggest advantage is that it does not require any downloading of software and, thus, does not have device compatibility issue. Instructors can create multiple choice or open-ended questions, and when activated, students can visit a web address to respond to the poll using their phones. In a study using a large computer science lecture class in the U.S., students responded that they found the class more enjoyable and felt more engaged when “Poll Everywhere” was used during lectures [

14]. Indeed, computer-mediated communication tools can provide students less threatening means to communicate resulting in engagement and confidence [

17], and anonymity helps students communicate without concerns about making mistakes [

6].

A study suggested that Chinese students demonstrate a lower level of creativity than American students because they have been exposed to education that predominantly emphasizes the learning of basic knowledge and analytical skills [

18]. While Asian students may shy away from in-class engagement affected by sociocultural values and attitudes toward education, some studies have shown that pedagogical practice matters more than students’ cultural background [

19]. Tran [

20] also claimed that learning style can be shaped by situational factors such as teaching methodologies. Therefore, the pedagogic practices might explain the passive learning styles of the Asian students, not the student learning styles. Rather than attributing low engagement to cultural background, testing different teaching methods to create an environment for the students to feel safe to make mistakes or share their views is needed.

Based on the discussion above, it is predicted that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Students will feel more comfortable responding to questions using their smartphones than verbally.

1.3. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and Intrinsic Motivation

Motivation is central to learning and scholars have examined such questions as what motivates students, what type of motivation is more effective in learning, and how to develop motivation [

21,

22,

23]. The assumption is that individuals are affected by internal and external environments and act based on individual internal structure, or intrinsic motivation [

21]. Intrinsic motivation refers to the innate human needs for competence and self-determination; when people are not under any type of external pressure (e.g., deadline, evaluation, reward), they have the propensity to seek challenges that suit their competencies and have the need to be self-determining and act out of choice [

21,

24]. In other words, when intrinsically motivated, people feel competent and self-determining, and as a result, they experience interest, enjoyment, and satisfaction with the given activity itself [

21].

In contrast, extrinsic motivation pertains to behaviors where an activity is performed for reasons not inherent to the task but as a means to an end [

21,

25]. Although people can be motivated to behave without extrinsic rewards or regulation, they are often vulnerable to external factors that affect individuals’ perceived choice. For example, an individual may be involved in an intrinsically interesting activity but face a situation where the causal responsibility for the activity shifts to external when the individual begins to receive rewards [

24].

Intrinsic motivation has been associated with positive cognitive, affective, and behavioral outcomes in educational settings [

24]. Students with high intrinsic motivation had better long-term memory and presented more school enjoyment, and students who are more motivated and self-determined to do schoolwork were more likely to stay in school than those with lower self-determined motivation [

22]. Therefore, it is predicted that when intrinsically motivated to participate in the in-class interactive poll, students will be highly interested in the activity itself and will develop positive attitudes toward interactive polling used in the classroom. As a result, students will find the class more engaging and feel they performed well. If these benefits to learning are felt by students with high intrinsic motivation, they will find using smartphones in class useful.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Students with high intrinsic motivation to engage in interactive polling will (a) have a more favorable attitude towards using interactive polling, (b) feel the class is more engaging, (c) have higher perceived learning, (d) feel they performed well on tests, and (e) feel using a smartphone in the classroom is more useful than those with low intrinsic motivation.

1.4. The Dark Side of Using Mobile Device in a Classroom

There is ample empirical evidence that shows the positive effect of the use of technology in higher education on academic achievement [

13], course completion, and reenrollment [

26]. Despite the positives, some instructors may be hesitant to incorporate interactive activity using technology due to several limitations. First, using a mobile device can become a source of frustration for students. For example, depending on the type of the phone a student possesses, there may be technical difficulties [

27]. Common technological problems include unreliable connection and potential compatibility problems across devices [

16,

28].

Second, allowing the use of a personal phone during class can open up opportunities for the students to be distracted from the course content. Supporting this line of reasoning, some studies provide a skeptical view of the pedagogical value of technology in classrooms. Some students find the device distracting as having the device easily accessible could potentially harm their concentration regarding the course materials [

27,

29]. Similarly, studies have found that the use of technology does not necessarily result in enhanced learning and students face lack of concentration and interruption of work when using mobile devices [

30,

31]. It is plausible that with limited cognitive resources, when students face more than a single task, their attention is divided and the encoding of information is disrupted [

32].

Lastly, permitting technology in classrooms can potentially provide some students to freely engage in non-class related activities with the instructor’s consent. A study has shown that students are likely to use mobile devices for non-academic entertainment purposes such as texting, instant messaging and playing games [

33] or browsing the Internet [

34] rather than for instructional purposes [

28].

However, when students are intrinsically motivated with in-class activities, they are less likely to view technology as a source of distraction but a tool for learning. Therefore, it is predicted that students with high intrinsic motivation participating in the interactive polling will be less affected by the negative side effects of accessing mobile devices during class.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Students with high intrinsic motivation engaging in interactive polling will (a) find the activity less boring and (b) less distracting than those with low intrinsic motivation.

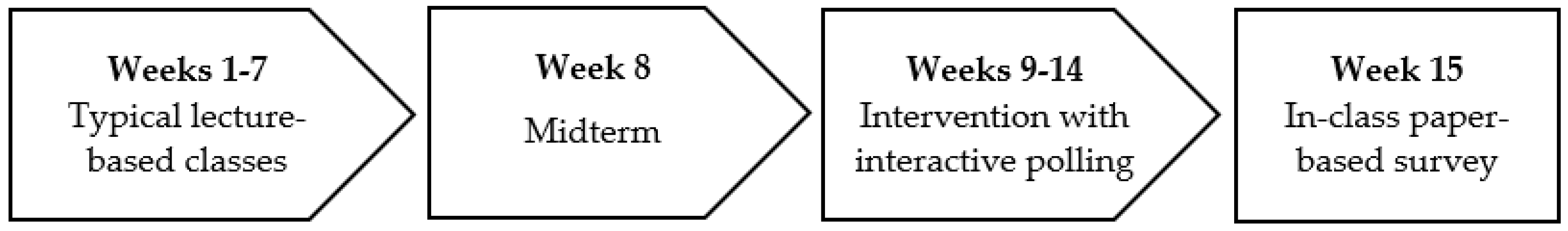

3. Results

3.1. The Mode of Interaction and the Level of Comfort Responding to Questions

A paired-sample t-test was conducted to compare students’ comfort levels with responding to questions verbally in class versus responding to the poll using their smartphones. Supporting H1, the means showed that students felt more comfortable responding to the poll (M = 5.19, SD = 0.93) than verbally responding to questions (M = 4.40, SD = 1.66), t(57) = 3.89, p < 0.001.

3.2. Intrinsic Motivation and Engagement

To compare students with high and low intrinsic motivation, participants were divided into two groups using a median split (the mean was 5.32 and the median was 5.33). A cut-off point of 5.33 was used; participants whose average intrinsic motivation score was 5.33 or lower were considered low intrinsic motivation group (n = 32; M = 4.58, SD = 0.77) and others were considered high intrinsic motivation group (n = 26; M = 6.22, SD = 0.37),

t(56) = 10.54,

p < 0.001. Each group’s means and standard deviations for the key measures can be found in

Table 1.

A series of analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was run to test H2 and H3 controlling for self-rated competency in English and self-efficacy in regards to the course because of their potential influences on intrinsic motivation and the dependent measures. The results showed significant differences between those who were high and low in their intrinsic motivation to participate in the interactive polling exercise. Those who showed high intrinsic motivation had more favorable attitudes toward interactive polling (F[1,54] = 35.81, p = 0.00, partial ω2 = 0.38), found the class more engaging (F[1,54] = 23.45, p = 0.00, partial ω2 = 0.29), felt they did better on tests because of the polling exercise (F[1,54] = 9.40, p = 0.00, partial ω2 = 0.13), showed higher level of perceived learning (F[1,54] = 16.17, p = 0.00, partial ω2 = 0.21) than those who reported low intrinsic motivation. Thus, H2(a), H2(b), H2(c), and H2(d) were supported.

However, there was no significance difference between the two groups on how students evaluated the usefulness of using smartphone in the classroom (F[1,54] = 2.59, p = 0.11, partial ω2 = 0.03). Therefore, H2(e) was not supported.

3.3. Intrinsic Motivation and the Dark Side of Using Interactive Polling

Students with varying levels of intrinsic motivation did not differ on their responses to the statement on what else they could be doing rather than answering the boring poll (F[1,53] = 0.56, p = 0.46, partial ω2 < 0.01). Thus, H3(a) was not supported. As predicted, students with low intrinsic motivation felt the classroom polling was more distracting (F[1,53] = 7.85, p = 0.01, partial ω2 = 0.11) than those with high intrinsic motivation, supporting H3(b).

4. Discussion

EMI in higher education is prevalent and is continuing to increase at universities across the globe [

3,

39,

40]. The problem is that, often, there is an imbalance between the instructor’s ability to communicate in English and students who are not fluent speakers of English. This creates a challenge in classrooms where learning the language is not necessarily the focus of study. A significant number of studies examine how to use mobile technology to support language learning [

41,

42,

43]; however, the primary goal of the courses taught in English at college level is for the students to learn the content. Acquiring language skill is merely a secondary goal. Therefore, research that focuses on using EMI to teach a specific content area is needed, and this study contributes to the literature by providing empirical evidence on how instructors can assist student learning of a subject area taught in their non-native language using interactive polling. The increased emphasis on EMI is not restricted to Korean universities. Stakeholders in higher education in other parts of Asian countries including Japan [

44] and China [

9,

20,

39,

40] are keen on pedagogical best practices. Thus, the results are applicable to neighboring Asian countries when adopting EMI.

Overall, this study successfully demonstrates the pedagogical value of using personal smartphones for college students to participate in interactive polling activities with the purpose of better engaging students who are taking courses in their non-native language. Students generally had a positive attitude towards the interactive poll, felt the activities made the class engaging, felt they performed better on tests because of the polling exercises, and felt the interactive activities using their smartphones was a useful addition to the class.

Students’ motivation towards interactive polling, however, moderated the effect. Students with high intrinsic motivation towards interactive poll showed a more favorable attitude toward the in-class activity, found the class more engaging, felt they did better on tests because of the polling exercise, and showed higher levels of perceived learning than those who reported low intrinsic motivation. The potential dark side of using smartphones in the classroom was not a critical problem for those with high intrinsic motivation—using smartphones for interactive polling is less distracting for the students with high intrinsic motivation than those with low intrinsic motivation. The varying responses based on motivation suggests that to successfully adopt interactive polling in class, creating interesting and fun exercises is essential to increase intrinsic motivation.

4.1. Practical Implications

First, the results suggest that utilizing technology to encourage student participation enhances learning. Whether instructors should allow the use of technology in the classroom, and to what extent, is a question that still lacks concrete answer. Some studies in the past have demonstrated the downsides of allowing technology use. For example, according to a study conducted with college students in Brazil, minutes spent on mobile phones, and especially during class, significantly reduced a student’s academic achievement [

45]. On the other hand, using technology is unavoidable when engaging with digital natives [

46]. The results of this study contribute to the body of knowledge that educators may adopt technology when using EMI to engage students with confidence. Consistent with previous studies [

14,

16,

47], students generally showed favorable attitudes toward the use of interactive polling using their smartphones. The concern that allowing smartphone use in classrooms distracts students was found not to be a problem in the current study. One potential explanation is that students are already tech savvy and have formed “hyperconnected relationship” with their devices [

48] so that multitasking is a natural practice among them. Of course, allowing smartphones or other mobile devices in the classroom without any restriction creates a different classroom climate compared to occasionally using smartphones to participate in polling exercises. Nevertheless, the results of this study do imply that guided use of a mobile device can enhance learning. Instead of banning mobile phone usage, it may benefit the students to experience how smartphones can be used for educational purposes, and more instructional methods need to be developed.

Second, when assigning an in-class activity, attaching points to every task is not always necessary. In the current study, students participated without any external reward (e.g., positive feedback, grade, etc.). Participating in the in-class activity was voluntary and the responses were collected anonymously. In other words, students engaged not for any type of reward but simply to be engaged with the task. Past studies have shown that student autonomy promotes student learning [

49] and keeps them more engaged [

50]. This leads to the issue of how to motivate the students. In the current study, a novel interactive polling tool was introduced to the students to increase engagement. The key finding here is that students need to have intrinsic motivation for engaging with the activity to maximize perceived learning. While the interactive polling tool used in the study was engaging, it lacked the competition aspect of gamification [

51,

52] that could further motivate the students and improve academic performance. Searching for and testing pedagogical practices that could add rewards without sacrificing intrinsic motivation is needed.

4.2. Limitations and Future Direction

One limitation of this study is that all measures were self-reported. While this is not problematic for most measures, the measure for competence in English, in particular, may not have provided an accurate assessment of students’ language competency. In future studies, measures such as English language competency or comprehension level could be replaced with standardized testing scores or grades for the course.

Another limitation is that the study was designed with one class. A small sample size was inevitable as only one section of the course was offered in English. As this was a foreseen limitation, the researcher took care to control for measures such as self-efficacy to examine the cause and effect relationship between the use of a smartphone on student learning. Lastly, when adopting and applying the method described in this study, one needs to note that the class was held at a large private university in Korea where English proficiency level is generally high. Nevertheless, students still find active class engagement difficult especially in an EMI setting that lacks instructional aid. A student population with lower English language competency may either benefit more from interactive polling or feel even more distracted, and this will need to be addressed in future studies.

As explained in the method section, the number of times the instructor engaged with students using the interactive polling was limited to two or three times per class period. This resulted in a positive outcome. However, there may be a boundary condition where when it reaches a certain level, too much interaction can become a source of distraction for the students.

Lastly, another recent phenomenon at Korean universities is the rising population of international students from both English-speaking and non-English speaking countries. In a typical undergraduate class, international students may take up anywhere from 10% to as much as almost 50% of the student body. This further complicates learning and engagement in the classroom and, thus, requires further research to assist student learning in such a diverse setting.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the effect of adopting an interactive polling exercise in class and allowing undergraduate students to participate in in-class activities using their own smartphones. The results showed positive effect of interactive polling by demonstrating that students feel more comfortable engaging with the instructor through mediated communication than providing verbal responses. Although students in general felt the interactive polling was a useful addition to the class, this effect was moderated by intrinsic motivation. When students found it enjoyable to participate in the interactive polling, they were more favorable towards the in-class activity. Those who scored high on intrinsic motivation felt more engaged with the class and had a more positive outlook towards their academic achievement than those who scored low. These findings add empirical evidence to the extant literature on SDT by showcasing that intrinsic motivation is key to classroom engagement.

A study has shown that students’ perception of an instructor’s readiness and skills to use a mobile device as an educational tool influences the behavioral intention of using a mobile device during class. Faculty members in higher education have expertise in their subject matter but may not be well trained as facilitators of technology for pedagogical use. Using technology in classrooms does not imply better engagement by default; integrating technology to better facilitate student learning requires careful planning and observation of the students, coupled with appropriate assessment. Therefore, before initiating application of interactive polling in the classroom, institutions should be aware of the faculty members’ capabilities in facilitating the class using technology.