Boards that Make a Difference in Firm’s Acquisitions: The Role of Interlocks and Former Politicians in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

Board Interlocks and Acquisitions

2.2. Former Politicians on Boards and Acquisitions

2.3. Regulated Industries

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Sample and Data Collection

2.4.2. Dependent Variables

2.4.3. Independent Variables

2.4.4. Control Variables

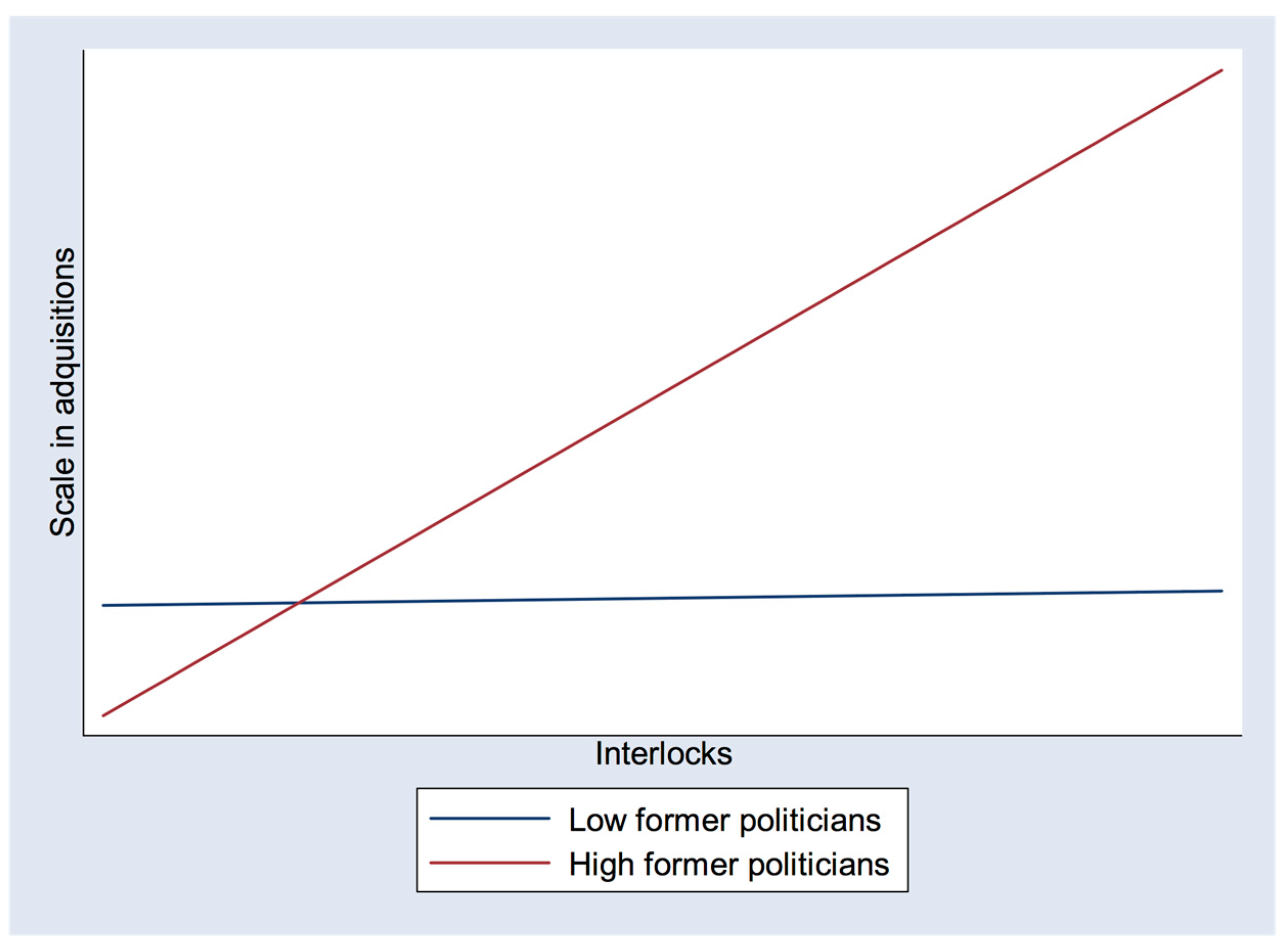

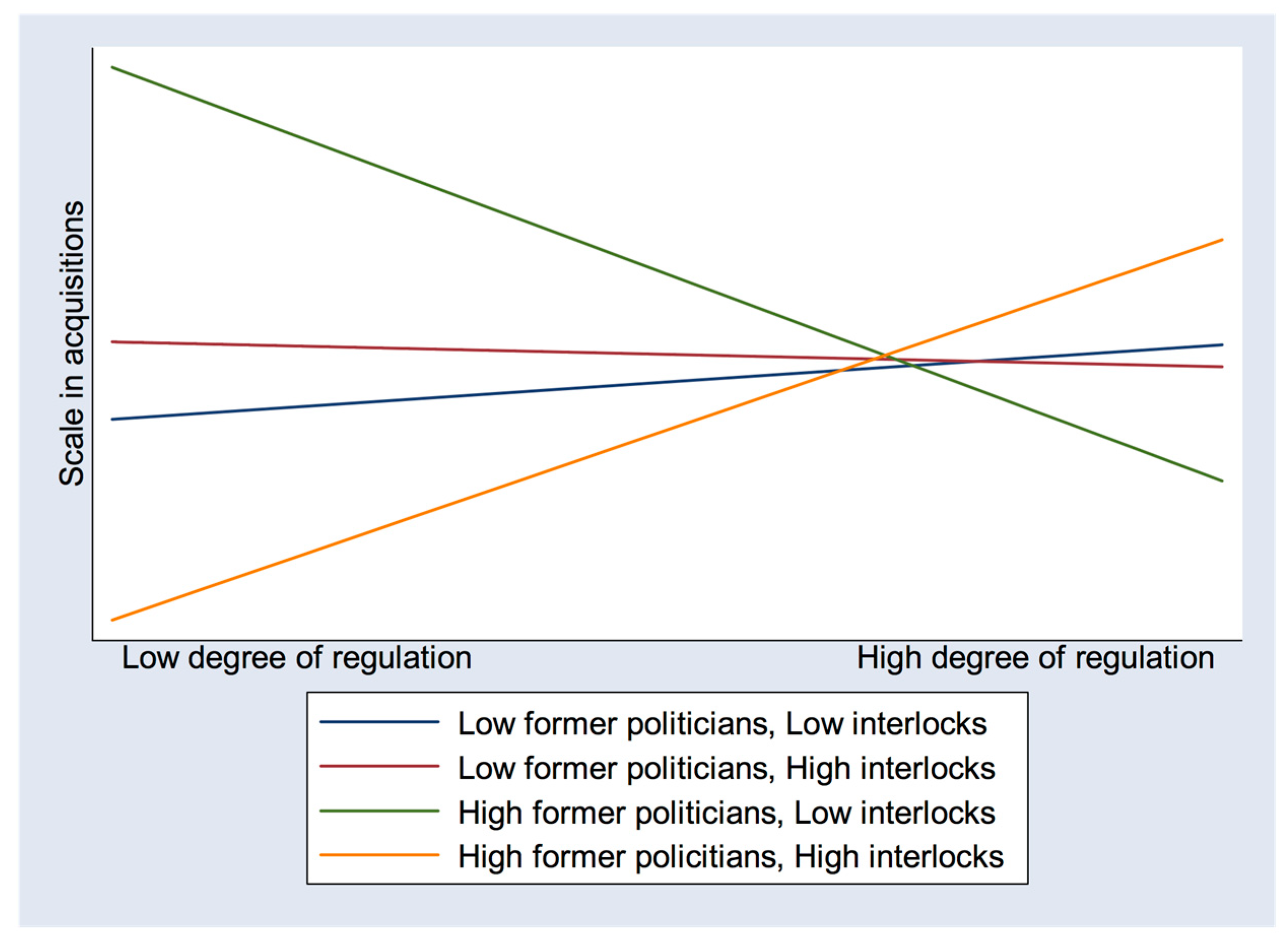

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mizruchi, M.S. What Do Interlocks Do? An Analysis, Critique, and Assessment of Research on Interlocking Directorates. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiazza, R.; Simoni, M. Directorate ties: A bibliometric analysis. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2837–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, R.H.; Hillman, A.; Zardkoohi, A.; Cannella, A.A. Former Government Officials as Outside Directors: The Role of Human and Social Capital. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shropshire, C. The Role of Interlocking Director and Board Receptivity in the Diffusion of Practices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 246–264. [Google Scholar]

- Acquaah, M. Managerial social capital, strategic orientation, and organizational performance in an emerging economy. Strat. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1235–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Cannella, A.A. Toward a Social Capital Theory of Director Selection. Corp. Governance: Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, J.D.; Zajac, E.J. Decoupling Policy from Practice: The Case of Stock Repurchase Programs. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Shim, J.W.; Kim, C.H.; Tuschke, A. How do board ties affect the adoption of new practices? The effects of managerial interest and hierarchical power. Corp. Govern. Int. Rev. 2020, 28, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haunschild, P.R. Interorganizational Imitation: The Impact of Interlocks on Corporate Acquisition Activity. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, J.D.; Zajac, E.J. Defections from the Inner Circle: Social Exchange, Reciprocity, and the Diffusion of Board Independence in U.S. Corporations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, E.; Perrone, G.; Kamuriwo, D.S. The interaction between inter-firm and interlocking directorate networks on firm’s new product development outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. Diversity of Board Interlocks and the Impact on Technological Exploration: A Longitudinal Study. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2019, 36, 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Xie, X.; Meng, X.; Yang, M. The diffusion of corporate social responsibility through social network ties: From the perspective of strategic imitation. Corp. Social Responsibility Environ. Manage. 2019, 26, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.F. Agents without Principles? The Spread of the Poison Pill through the Intercorporate Network. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, P.; Hadani, M.; Goranova, M. Stock options expensing: An examination of agency and institutional theory explanations. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Westphal, J.D. Cooperative or Controlling? The Effects of CEO-Board Relations and the Content of Interlocks on the Formation of Joint Ventures. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D.A.; Jennings, P.D.; Zhou, X. Late Adoption of the Multidivisional Form by Large U.S. Corporations: Institutional, Political, and Economic Accounts. Adm. Sci. Q. 1993, 38, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betton, S.; Eckbo, B.E.; Thorburn, K.S. Merger negotiations and the toehold puzzle. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 91, 158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.V.; Schonlau, R.J. Board Networks and Merger Performance (September 8, 2009). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1322223 (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Cai, Y.; Sevilir, M. Board connections and M&A transactions. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 103, 327–349. [Google Scholar]

- Aktas, N.; Croci, E.; Simsir, S.A. Corporate Governance and Takeover Outcomes. Corp. Govern. 2016, 24, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haunschild, P.R. How Much is That Company Worth?: Interorganizational Relationships, Uncertainty, and Acquisition Premiums. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renneboog, L.; Zhao, Y. Director networks and takeovers. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 28, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, S.P.; Houston, R.; Javakhadze, D. Friends in the right places: The effect of political connections on corporate merger activity. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 41, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, N.H.; Roundy, P. The “ties that bind” board interlocks research: A systematic review. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1516–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.; Li, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, Y. The dark side of board network centrality: Evidence from merger performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haunschild, P.R.; Beckman, C.M. When Do Interlocks Matter?: Alternate Sources of Information and Interlock Influence. Adm. Sci. Q. 1998, 43, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drees, J.M.; Heugens, P.P.M.A.R. Synthesizing and Extending Resource Dependence Theory: A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1666–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R.; Zhang, C.M. Institutional Logics and Power Sources: Merger and Acquisition Decisions. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J. Politicians on the Board of Directors: Do Connections Affect the Bottom Line? J. Manag. 2005, 31, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.; Harymawan, I.; Nowland, J. Political and government connections on corporate boards in Australia: Good for business? Aust. J. Manag. 2014, 41, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, R.; Lamont, B.T.; Harris, R.J. Managerial Control in Mergers of Equals: The Role of Political Skill. J. Manag. Issues 2016, 28, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, P.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lau, S.H. The Performance Impact of Interlocking Directorates: The Case of Singapore. J. Manag. Issues 2003, 15, 338–352. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.S. Discussion of What Determines Corporate Transparency? J. Account. Res. 2004, 42, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.A. Auditors’ Response to Political Connections and Cronyism in Malaysia. J. Account. Res. 2006, 44, 931–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.R.; Santor, E. Family values: Ownership structure, performance and capital structure of Canadian firms. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 2423–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona-Sánchez, C.; Pérez-Alemán, J.; Santana-Martín, D.J. Politically Connected Firms and Earnings Informativeness in the Controlling versus Minority Shareholders Context: European Evidence. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2014, 22, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalate, D.; Bel, G.; González-Gómez, F.; Picazo-Tadeo, A.J. Weakening political connections by means of regulatory reform: Evidence from contracting out water services in Spain. J. Regul. Econ. 2017, 52, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S.B.; Schlingemann, F.P.; Stulz, R.M. Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. J. Financ. Econ. 2004, 73, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Kroll, M.; Wright, P. Outside board monitoring and the economic outcomes of acquisitions: A test of the substitution hypothesis. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 926–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S.B.; Schlingemann, F.P.; Stulz, R.M. Wealth Destruction on a Massive Scale? A Study of Acquiring-Firm Returns in the Recent Merger Wave. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 757–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.L.; Mulherin, J. The impact of industry shocks on takeover and restructuring activity. J. Financ. Econ. 1996, 41, 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, J. What drives merger waves? J. Financ. Econ. 2005, 77, 529–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redor, E. Board attributes and shareholder wealth in mergers and acquisitions: A survey of the literature. J. Manag. Govern. 2016, 20, 789–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, B.A.; Kroll, M.J.; Wright, P. CEO tenure, boards of directors, and acquisition performance. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Ownership participation of cross-border mergers and acquisitions by emerging market firms. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goranova, M.; Dharwadkar, R.; Brandes, P. Owners on both sides of the deal: Mergers and acquisitions and overlapping institutional ownership. Strat. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1114–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, A.K.; Findley, M.; Jensen, N.M.; Meier, S.; Nielson, D. Field experiments in strategy research. Strat. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. The Mergers & Acquisitions Review; Law Business Research Ltd: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, S.; Hopkins, S. Mergers & Acquisitions: Spain; Global Legal Insights: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, S.; Bolotnikova, I. The Deloitte M&A Index 2016; Opportunities Amidst Divergence: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, J.; Xuan, Y. Acquirer-target social ties and merger outcomes. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 112, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, A.B.; Malmendier, U.; Tate, G. Financial expertise of directors. J. Financ. Econ. 2008, 88, 323–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Jiang, F.; Lie, E.; Yang, K. The role of investment banker directors in M&A. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 112, 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, R. Where M&A Pays and Where It Strays: A Survey of the Research. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2004, 16, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof, G.A. The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism*. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.C.; Majluf, N.S. Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. J. Financ. Econ. 1984, 13, 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, C.M.; Haunschild, P.R. Network Learning: The Effects of Partners’ Heterogeneity of Experience on Corporate Acquisitions. Adm. Sci. Q. 2002, 47, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.E.; Yim, S. Board interlocks and the propensity to be targeted in private equity transactions. J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 97, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuil, D.A.; Datta, D.K. Value creation in cross-border acquisitions: The role of outside directors’ human and social capital. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Fuster, B.; Crespí-Cladera, R. Politicians in the boardroom: Is it a convenient burden? Corp. Governance: Int. Rev. 2018, 26, 448–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, R.; Ferris, S. Does the revolving door swing both ways? The value of political connections to US firms. Manag. Financ. 2015, 41, 1002–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, J.C.; Yuan, D.; Chansog, K. High-level politically connected firms, corruption, and analyst forecast accuracy around the world. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 1505. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Knoeber, C.R. Do Some Outside Directors Play a Political Role? J. Law Econ. 2001, 44, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, E.; Rocholl, J.; So, J. Do Politically Connected Boards Affect Firm Value? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 2331–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M. Politically Connected Firms. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaja, A.I.; Mian, A. Do Lenders Favor Politically Connected Firms? Rent Provision in an Emerging Financial Market. Q. J. Econ. 2005, 120, 1371–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-H.; Shu, P.-G.; Chiu, S.-B. Political connections, corporate governance and preferential bank loans. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2013, 21, 1079–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J.; Gülen, H.; Ovtchinnikov, A.V. Corporate Political Contributions and Stock Returns. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 687–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.D.; Bennedsen, M. The value of local political connections in a low-corruption environment. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 110, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, A.; Ruenzi, S. Political Connectedness and Firm Performance: Evidence from Germany. Ger. Econ. Rev. 2010, 11, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meca, E.; Palacio, C.J. Board composition and firm reputation: The role of business experts, support specialists and community influentials. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018, 21, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Cannella, A.A.; Paetzold, R.L. The Resource Dependence Role of Corporate Directors: Strategic Adaptation of Board Composition in Response to Environmental Change. J. Manag. Stud. 2000, 37, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratmann, T. Can Special Interests Buy Congressional Votes? Evidence from Financial Services Legislation. J. Law Econ. 2002, 45, 345–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D.; Schuler, D. Corporate Political Activity: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaggia, J.; Cornaggia, K.J.; Xia, H. Revolving doors on Wall Street. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 120, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Hitt, M.A. Corporate Political Strategy Formulation: A Model of Approach, Participation, and Strategy Decisions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Industrial dynamics and managerial networking in an emerging market: The case of China. Strat. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, S.; Kimino, S.; Pye, A. Interlocking directorships and firm performance in highly regulated sectors: The moderating impact of board diversity. J. Manag. Govern. 2014, 18, 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helland, E.; Sykuta, M. Regulation and the Evolution of Corporate Boards: Monitoring, Advising, or Window Dressing? J. Law Econ. 2004, 47, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadani, M.; Schuler, D.A. In search of El Dorado: The elusive financial returns on corporate political investments. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, D.; Vedres, B. Political Holes in the Economy: The Business Network of Partisan Firms in Hungary (translated by Alexander Kurakin). J. Econ. Sociol. 2012, 13, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonardi, J.-P.; Hillman, A.J.; Keim, G.D. The Attractiveness of Political Markets: Implications for Firm Strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 397–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, N.; Guedhami, O.; Mishra, D.; Saffar, W. Political connections and the cost of equity capital. J. Corp. Financ. 2012, 18, 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C. The Modern Industrial Revolution, Exit, and the Failure of Internal Control Systems. J. Financ. 1993, 48, 831–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Dalziel, T. Boards of Directors and Firm Performance: Integrating Agency and Resource Dependence Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C.M.; Dalton, D.R.; Cannella, A.A. Corporate Governance: Decades of Dialogue and Data. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, W.B.; Radin, R.F. Social Capital and Social Influence on the Board of Directors. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 16–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracassi, C.; Tate, G. External Networking and Internal Firm Governance. J. Financ. 2012, 67, 153–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.A.; Zahra, S.A. Board Composition from a Strategic Contingency Perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 411–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile, A.I.; Fradejas, N.A. Ownership structure and board composition in a high ownership concentration context. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of Ownership and Control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.G.; Ketchen, D.J.; Perryman, A.A.; Donahue, M.S. The Moderating Effect of CEO Power on the Board Composition? Firm Performance Relationship. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kor, Y.Y.; Sundaramurthy, C. Experience-Based Human Capital and Social Capital of Outside Directors. J. Manag. 2008, 35, 981–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faleye, O.; Hoitash, R.; Hoitash, U. The costs of intense board monitoring. J. Financ. Econ. 2011, 101, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, K.T.; Hillman, A. The effect of board capital and CEO power on strategic change. Strat. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wincent, J.; Anokhin, S.; Örtqvist, D. Does network board capital matter? A study of innovative performance in strategic SME networks. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, C.; Gutierrez, L.H. Outside directors, board interlocks and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Colombian business groups. J. Econ. Bus. 2011, 63, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, F.R. Managerial Objectives in Regulated Industries: Expense-Preference Behavior in Banking. J. Polit. Econ. 1977, 85, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhmatovskiy, I. Performance Implications of Ties to the Government and SOEs: A Political Embeddedness Perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1020–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, G.; Mehta, B.; Bose, S.; Pekny, J.; Sinclair, G.; Keunker, K.; Bunch, P. Risk management in the development of new products in highly regulated industries. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2000, 24, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. Using the Margins Command to Estimate and Interpret Adjusted Predictions and Marginal Effects. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2012, 12, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Size and Composition of Corporate Boards of Directors: The Organization and its Environment. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, P.; Singh, H.; Perlmutter, H. Learning and Protection of Proprietary Assets in Strategic Alliances: Building Relational Capital. Strat. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goranova, M.L.; Priem, R.L.; Ndofor, H.A.; Trahms, C.A. Is there a “Dark Side” to Monitoring? Board and Shareholder Monitoring Effects on M&A Performance Extremeness. Strat. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2285–2297. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, R.V. Directorship Interlocks in Comparative Perspective: The Case of Spain. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 1998, 14, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, T.; Oliver, C.; Roy, J.P. The Legitimacy of Strategic Alliances: An Institutional Perspective. Strat. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.B.; E Hermalin, B.; Weisbach, M.S. The Role of Boards of Directors in Corporate Governance: A Conceptual Framework and Survey. J. Econ. Lit. 2010, 48, 58–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, D.; Milliken, F. Cognition and Corporate Governance: Understanding Boards of Directors as Strategic Decision-Making Groups. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fich, E.M.; Shivdasani, A. Are Busy Boards Effective Monitors? J. Financ. 2006, 61, 689–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subrahmanyam, A. Social Networks and Corporate Governance. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2008, 14, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E. Director Interlocks and Spillover Effects of Reputational Penalties from Financial Reporting Fraud. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R. Estimating the Value of Political Connections. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, C.; Oberholzergee, F. Political relationships, global financing, and corporate transparency: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Financ. Econ. 2006, 81, 411–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, H.; Joseph, S. Changes in Malaysia: Capital controls, prime ministers and political connections. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2010, 18, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Scale in acquisitions | 0.00 | 0.70 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. Interlocks | 1.61 | 1.37 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 3. Politicians on board | 10.66 | 11.65 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4. Government control | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.07 | −0.13 *** | −0.11 ** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5. Log firm size | 6.08 | 2.24 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.27 *** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 6. Firm´s previous performance | 3.22 | 20.97 | −0.05 | 0.11 ** | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |||||

| 7. Board size | 13.54 | 3.72 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.28 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.21 *** | −0.08 | 1.00 | ||||

| 8. Percentage of non-executive directors | 0.82 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.13 *** | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.20 *** | −0.17 *** | 0.10 * | 1.00 | |||

| 9. Log industry velocity | 3.91 | 2.08 | −0.07 | 0.13 *** | 0.00 | −0.62 *** | −0.23 *** | 0.05 | −0.09 * | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||

| 10. Temporal effects | -- | -- | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 *** | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.14 *** | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 1.00 | |

| 11. Company effects | -- | -- | 0.04 | 0.12 ** | −0.02 | −0.42 *** | 0.23 *** | −0.04 | −0.17 *** | 0.04 | 0.39 *** | −0.08 * | 1.00 |

| Control Variables and Independent and Moderating Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables | ||||||

| Log firm size | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Firm´s previous performance | 0.00 | 0.00 * | 0.00 * | 0.00 | 0.00 ** | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Board size | −0.26 | −0.27 ** | v0.24 * | −0.30 ** | −0.25 * | −0.36 |

| (0.13) | (0.13) | (0.14) | (0.15) | (0.14) | (0.14) | |

| Percentage of non-executive directors | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Log industry velocity | 0.00 | 0.00 * | 0.00 * | 0.00 ** | 0.00 * | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00 | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Temporal effects | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.03) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Company effects | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Independent and moderating variables | ||||||

| Interlocks (H1) | 0.04 ** | 0.03 * | 0.01 | 0.04 * | 0.14 ** | |

| (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.06) | ||

| Politicians on board | 0.00 | −0.01 ** | 0.00 | 0.13 ** | ||

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.05) | |||

| Interlocks * Politicians on board (h2) | 0.00 *** | −0.07 *** | ||||

| (0.00) | (0.02) | |||||

| Degree of regulation | −0.09 | 0.35 | ||||

| (0.14) | (0.32) | |||||

| Interlocks * degree of regulation | −0.14 * | |||||

| (0.07) | ||||||

| Politicians on board * degree of regulation | −0.14 *** | |||||

| (0.05) | ||||||

| Interlocks * Politicians on board * degree of regulation (h3) | 0.08 *** | |||||

| (0.02) | ||||||

| Observations | 479 | 479 | 479 | 479 | 479 | 479 |

| R2 | 14.5 | 17.2 | 17.8 | 20.8 | 18.3 | 28.1 |

| F Statistic | 3.07 *** | 3.44 *** | 3.16 *** | 3.11 *** | 2.86 *** | 7.16 *** |

| Pair of Slopes | t-Value for Slope Difference | p-Value for Slope Difference |

|---|---|---|

| (1) and (2) | −2.77 | 0.01 |

| (1) and (3) | −1.95 | 0.04 |

| (1) and (4) | 3.89 | 0.00 |

| (2) and (3) | 2.70 | 0.01 |

| (2) and (4) | 3.72 | 0.00 |

| (3) and (4) | 3.91 | 0.00 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kopoboru, S.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, G.; Pérez-Calero, L. Boards that Make a Difference in Firm’s Acquisitions: The Role of Interlocks and Former Politicians in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030984

Kopoboru S, Cuevas-Rodríguez G, Pérez-Calero L. Boards that Make a Difference in Firm’s Acquisitions: The Role of Interlocks and Former Politicians in Spain. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030984

Chicago/Turabian StyleKopoboru, Santiago, Gloria Cuevas-Rodríguez, and Leticia Pérez-Calero. 2020. "Boards that Make a Difference in Firm’s Acquisitions: The Role of Interlocks and Former Politicians in Spain" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030984

APA StyleKopoboru, S., Cuevas-Rodríguez, G., & Pérez-Calero, L. (2020). Boards that Make a Difference in Firm’s Acquisitions: The Role of Interlocks and Former Politicians in Spain. Sustainability, 12(3), 984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030984