Planning the Flows of Residual Biomass Produced by Wineries for the Preservation of the Rural Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Residual Biomass Produced by Wineries

3. Materials and Methods

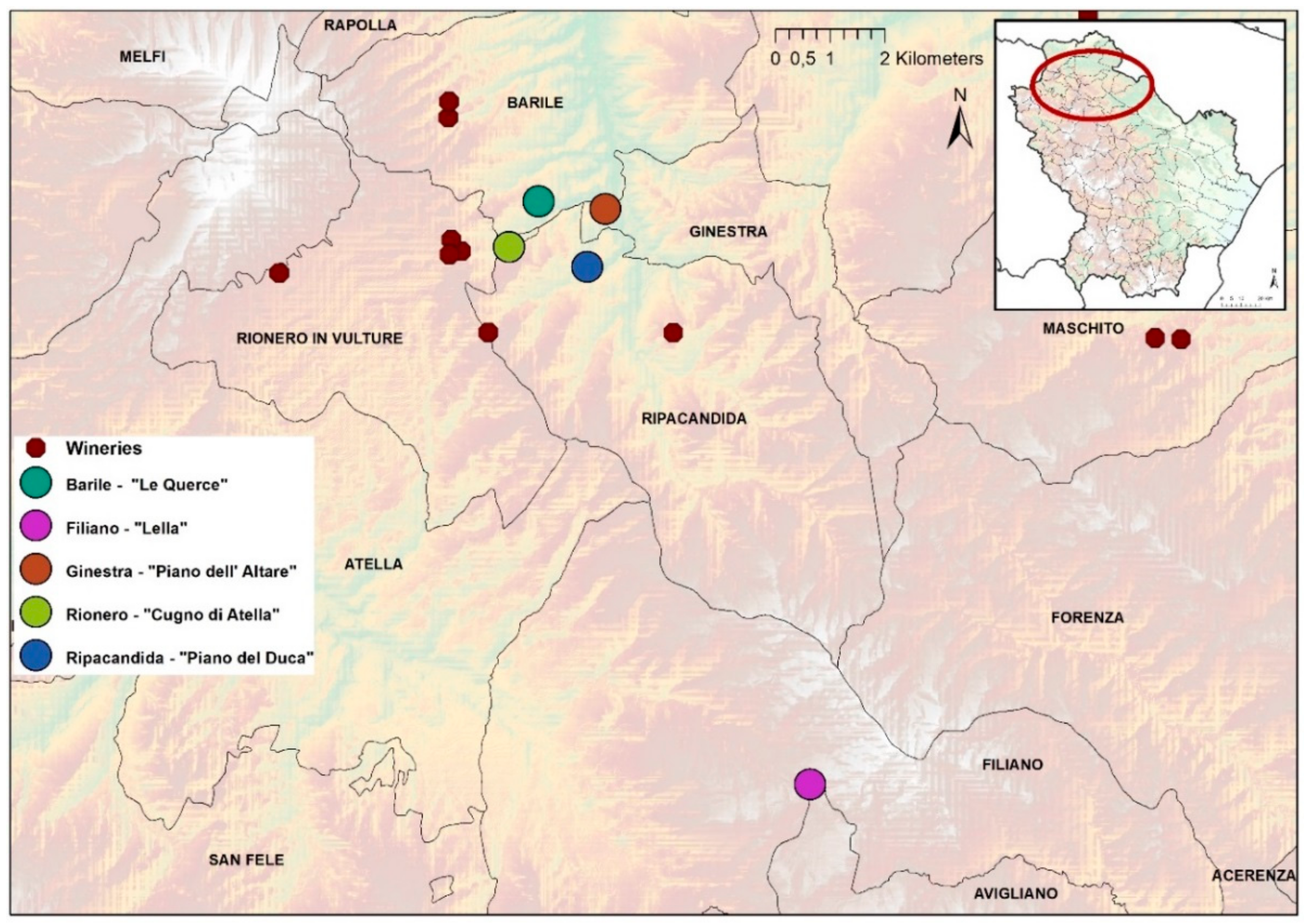

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Analysis of the Soil Organic Matter

4. Results

5. Discussion

- Direct spreading on the ground: this practice is very simple and allows the spreading on lands, in particular vineyards. It is not a very advantageous practice for farms because it is necessary to respect a series of constraints imposed by the legislation (in Italy, the DGR n. 8/5868 of 11/21/2007 and n. IX/2208 of 09/14/2011) linked first of all to the quantity and the extension of the surface. Furthermore, the residues must be appropriately treated before being applied to the soil, since they contain some characteristics that could cause collateral unfavorable effects, such as the alcohol content or the high content of polyphenols. These elements could give the soil too much macronutrients, thus giving rise to a general negative effect.

- Mixed with other agricultural residues to produce compost: this practice is much more used and convenient for wineries or farms as it contributes to the improvement of the content of organic matter. It represents a technically and economically advantageous process, with low environmental impacts. This organic matter increases microbial biomass and helps to maintain the beneficial bacterial and fungi populations. In addition, there are economic advantages, since the use of residues involves lower costs than those related to conventional materials [51,52]. Particularly, the compost obtained is recommended for application to the soils, because the nitrogen is gradually released, leaving the soil time to absorb it.

- Positive consequences on the concentration of many macro nutrients, the mineralization of the organic substance causes the release of the contained macronutrients, which can then be absorbed and used by the soil.

- The improvement of the structure of the soil and maintenance of the pH at values close to neutrality. Neutral soils are the most suitable for agriculture because most agricultural species adapt optimally to pH values between 6.5 and 7.5.

- The conservation of soil biodiversity and limitation of erosion since the organic fraction is a source for a wide range of organisms [53].

- Mitigation of climate change, in this context, the recycling of organic residues allows to combat carbon emissions into the environment (e.g., CO2), co-responsible for the greenhouse effects. Globally, soil stores about twice as much carbon in the atmosphere and three times as much carbon as vegetation. Therefore, agricultural soils are a huge storage tank for organic carbon [50].

- Preservation of the rural landscape, thanks to the natural restoration of soil fertility, without introducing chemical/artificial fertilizers, which may transform, in the long time, the main features of the soil, then the consequent vegetation and associated ecosystems.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carus, M.; Dammer, L. The Circular Bioeconomy—Concepts, Opportunities, and Limitations. Ind. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M. Plan A; Marks & Spencer. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Lahti, T.; Wincent, J.; Parida, V. A Definition and Theoretical Review of the Circular Economy, Value Creation, and Sustainable Business Models: Where Are We Now and Where Should Research Move in the Future? Sustainability 2018, 10, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, L.; Wurpel, G.; Ten Wolde, A. Unleashing the Power of the Circular Economy; Circle Economy: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Europæiske Miljøagentur Circular by Design: Products in the Circular Economy; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liebert, M.A. Innovating for Sustainable Growth: A Bioeconomy for Europe. Ind. Biotechnol. 2012, 8, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Statuto, D.; Picuno, P. Improving the greenhouse energy efficiency through the reuse of agricultural residues. Acta Hortic. 2017, 1170, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statuto, D.; Frederiksen, P.; Picuno, P. Valorization of Agricultural By-Products within the “Energyscapes”: Renewable Energy as Driving Force in Modeling Rural Landscape. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 28, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, F.; Porto, S.M.C.; Chinnici, G.; Cascone, G.; Arcidiacono, C. Assessment of citrus pulp availability for biogas production by using a gis-based model: The case study of an area in southern Italy. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 58, 529–534. [Google Scholar]

- Statuto, D.; Bochicchio, M.; Sica, C.; Picuno, P. Experimental development of clay bricks reinforced with agricultural by-products. In Proceedings of the 46th Symposium on: “Actual Tasks on Agricultural Engineering—ATAE 2018, Opatija, Croatia, 27 February–2 March 2018; pp. 595–604. [Google Scholar]

- Statuto, D.; Picuno, P. Analysis of renewable energy and agro-food by-products in a rural landscape: The Energyscapes. In Proceedings of the 4th CIGR International Conference of Agricultural Engineering (CIGR-AgEng 2016), Aarhus, Denmark, 26–29 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hossner, L.R.; Juo, A.S.R. Soil Nutrient Management for Sustained Food Crop Production in Upland Farming Systems in the Tropics; Soil and Crop Sciences Department College Station: College Station, TX, USA, 1999; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Gruhn, P.; Goletti, F.; Yudelman, M. Integrated Nutrient Management, Soil Fertility, and Sustainable Agriculture: Current Issues and Future Challenges; Food, Agriculture, and the Environment Discussion Paper 32; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Woomer, P.L.; Martin, A.; Albrecht, A.; Resck, D.V.S.; Scharpenseel, H.W. The importance and management of soil organic matter in the tropics. In The Biological Management of Tropical Soil Fertility; Woomer, P.L., Swift, M.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1994; pp. 47–80. [Google Scholar]

- Università Politecnica delle Marche. I sottoprodotti agroforestali e industriali a base rinnovabile. Extravalore–Progetto MiPAAF Bando Settore Bioenergetico DM246/07; Università Politecnica delle Marche: Ancona, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Z.; Jin, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. Utilization of winery wastes for Trichoderma viride biocontrol agent production by solid state fermentation. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziri, E.; Mantzouridou, F.; Tsimidou, M.Z. Recovery of Squalene from Wine Lees Using Ultrasound Assisted Extraction—A Feasibility Study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9195–9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlack, R.A.; Potumarthi, R.; Jeffery, D.W. Sustainable wineries through waste valorization: A review of grape marc utilization for value-added products. Waste Manag. 2018, 72, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafka, T.I.; Sinanoglou, V.; Lazos, E.S. On the extraction and antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds from winery wastes. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.A.S.; Xavier, A.M.R.B.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Lopes, L.P.C. Integrated utilization of grape skins from white grape pomaces. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 49, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Paredes, C.; Pérez-Espinosa, A.; Moreno-Caselles, J.; Pérez-Murcia, M.D. Agrochemical characterisation of the solid by-products and residues from the winery and distillery industry. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eyk, P.; Ashman, P. Utilisation of Winery Waste Biomass in Fluidised Bed Gasification and Combustion; South Australian Coal Research Laboratory, School of Chemical Engineering, The University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pavan, C.P.; Libralato, D.G.; Finesso, A. Valorizzazione di scarti vinicoli per il recupero di prodotti ad alto valore aggiunto ed energia. Tesi di laurea magistrale, Università Cà Foscari, Venezia, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rugani, B.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Benedetto, G.; Benetto, E. A comprehensive review of carbon footprint analysis as an extended environmental indicator in the wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccia, P. Ethics + economy + environment = sustainability: Gambero Rosso on the front lines with a new concept of sustainability. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, C.; Cavinato, C.; Pavan, P.; Bolzonella, D. Winery waste recycling through anaerobic co-digestion with waste activated sludge. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2028–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amienyo, D.; Camilleri, C.; Azapagic, A. Environmental impacts of consumption of Australian red wine in the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, K.L. Critical environmental concerns in wine production: An integrative review. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, C.; Costa, G.N.S.; Cabezudo, I.; Da Silva-James, N.K.; Teles, A.S.C.; Cruz, A.P.G.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Tonon, R.V.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Freitas, S.P. Towards integral utilization of grape pomace from winemaking process: A review. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, L.; Cadena, E.; Martínez-Blanco, J.; Gasol, C.M.; Rieradevall, J.; Gabarrell, X.; Gea, T.; Sort, X.; Sánchez, A. Recovery of organic wastes in the Spanish wine industry. Technical, economic and environmental analyses of the composting process. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilla-Rivera, O.; Moldes, A.; Torrado, A.; Domínguez, J. Lactic acid and biosurfactants production from hydrolyzed distilled grape marc. Process Biochem. 2007, 42, 1010–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilla-Rivera, O.M.; Torrado, A.M.; Domínguez, J.M.; Moldes, A.B. Stabilization of Kerosene/Water Emulsions Using Bioemulsifiers Obtained by Fermentation of Hemicellulosic Sugars with Lactobacillus pentosus. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2010, 58, 10162–10168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, L.; Brosse, N.; Chrusciel, L.; Navarrete, P.; Pizzi, A. Extraction of condensed tannins from grape pomace for use as wood adhesives. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorngate, J.H.; Singleton, V.L. Localization of Procyanidins in Grape Seeds. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1994, 45, 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Karleskind, A. Association française pour l’étude des corps gras. In Manuel des corps gras; Technique et Documentation–Lavoisier: Paris, France; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.; Diánez, F.; de Cara, M.; Tello, J.C. Possibilities of the use of vinasses in the control of fungi phytopathogens. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 9040–9043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versari, A.; Castellari, M.; Spinabelli, U.; Galassi, S. Recovery of tartaric acid from industrial enological wastes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2001, 76, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.G.; Lenskart e Silva, F.A.; Alves, A. Recovery of Winery by-products in the Douro Demarcated Region: Production of Calcium Tartrate and Grape Pigments. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 2002, 53, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, M.J.; Madejón, E.; López, F.; López, R.; Cabrera, F. Optimization of the rate vinasse/grape marc for co-composting process. Process Biochem. 2002, 37, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustin, M. Le compost: Gestion de la matière organique/Michel Mustin; François Dubusc: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, J. Agronomic use of biotechnologically processed grape wastes. Bioresour. Technol. 2001, 76, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Paredes, C.; Perez-Murcia, M.D.; Pérez-Espinosa, A.; Moreno-Caselles, J.; Moral, R. Winery and distillery waste management: Perspective and potential future uses. In Proceedings of the II International Symposium on Agricultural and Agroindustrial Waste Management (SIGERA), Foz de Iguatu, Brazil, 15–17 March 2011; Volume 28, pp. 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Picuno, P.; Cillis, G.; Statuto, D. Investigating the time evolution of a rural landscape: How historical maps may provide environmental information when processed using a GIS. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 139, 105580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbistat-Geomarketing and Market Research. Available online: http://ugeo.urbistat.com (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- ISTAT (Italian National Institute for Statistic). Available online: http://istat.it (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- RSDI—Regional Spatial Data Infracstructure—Map of land use. Available online: http://rsdi.regione.basilicata.it (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- Regione Basilicata—I suoli della Basilicata: Le carte derivate. Available online: http://basilicatanet.it/suoli (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Regione Basilicata—Dipartimento Politiche Agricole e Forestali Ufficio Fitosanitario. I Disciplinari di produzione integrata della Regione Basilicata; Regione Basilicata: Potenza, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miele, S.; Marmugi, M.; Bargiacchi, E.; Foschi, L. Evoluzione della tecnologia produttiva nel vigneto—Gestione agronomica del suolo e nutrizione vegetale; Montalcino: Siena, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sorrenti, G.; Toselli, M.; Baldi, E.; Quartieri, M.; Marcolini, G.; Bravo, K.; Marangoni, B. L’importanza della sostanza organica nella gestione sostenibile del suolo per una frutticoltura efficiente. Frutticoltura 2011, 3, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Ladas, D.; Mavromatis, A. Potential uses and applications of treated wine waste: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2006, 41, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, M. Los sustratos horticolas y tecnicas de cultivo sin suelo. In La horticultura Espanola; Rallo, L., Nuez, F., Eds.; Tarragona: Reus, Spain, 1991; pp. 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Leginio, M.D.; Fumanti, F.; Giandon, P.; Vinci, I. L’importanza della sostanza organica nei suoli: La situazione in italia e il progetto sias. Reticula 2014, 7, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Agenzia Europea dell’Ambiente. A Proposito Dello Sfruttamento del Suolo. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu (accessed on 11 October 2019).

- Statuto, D.; Tortora, A.; Picuno, P. Analysis of the evolution of landscape and land use in a gis approach. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Agricultural Engineering—ISAE 2013, Belgrade, Serbia, 4–6 October 2013; Volume VI, pp. 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Blanschke, T.; Biberacher, M.; Gadocha, S.; Schardinger, I. ‘Energy landscapes’: Meeting energy demands and human aspirations. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 55, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Entrance (kg) | Exit (kg) | Residues Classifiable as by-Products (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grapes (100 Kg) | Wine (77 Kg) | Virgin (5.4) and exhausted pomace (4.6) | 10 |

| Grapeseeds | 5 | ||

| Stalks | 3 | ||

| Dregs | 5 | ||

| Parameter | Value | Reference | Parameter | Stalks | Pomace | Dregs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph | 3.6 ± 0.2 | [19] | pH | 4.4 | 3.8 | 4 | [21] |

| Moisture | 73.6 ± 2.6% w/w | Organic Substance (g/kg) | 920 | 915 | 759 | ||

| Reducing sugars | 1.5 ± 0.3% w/w | Oxidizable organic carbon (g/kg) | 316 | 280 | 300 | ||

| Ash | 4.6 ± 0.5% w/w | Water soluble carbon (g/kg) | 74.5 | 37.4 | 87.8 | ||

| Cellulose | 20.8 % w/w | [20] | Total nitrogen (g/kg) | 12.4 | 20.3 | 35.2 | |

| Hermicelluloses | 12.5 % w/w | P (g/kg) | 0.94 | 1.15 | 4.94 | ||

| Tannins | 13.8 % w/w | K (g/kg) | 30 | 24.2 | 72.8 | ||

| Proteins | 18.8 % w/w | Ca (g/kg) | 9.5 | 9.4 | 9.2 | ||

| Ash | 7.8 % w/w | Mg (g/kg) | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.6 | ||

| Fe (mg/kg) | 128 | 136 | 357 | ||||

| Mn (mg/kg) | 25 | 12 | 12 | ||||

| Cu (mg/kg) | 22 | 28 | 189 | ||||

| Zn (mg/kg) | 26 | 24 | 46 |

| Wine Industry: Process Steps | Environmental Risk |

|---|---|

| Grape culture | Pesticides, fertilizers, water supply and fuel |

| Packaging | Glass bottles and paper labels |

| Vinification | Electricity, water, sulphur dioxide and sodium hydroxide |

| Transport | Fuel |

| Waste management | Effluents, wastewater and grape pomace |

| Soil Parameter | Barile “Le Querce” | Filiano “Lella” | Ginestra “Piano dell’Altare” | Rionero “Cugno di Atella” | Ripacandida “Piano del Duca” | Acceptability Range * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOM (g/Kg) | 8.69 | 24.3 | 22.24 | 19.31 | 15.9 | 15–20 g/Kg |

| Total N (g/Kg) | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1–1.8 g/Kg |

| Total P (g/Kg s.s.) | 1.38 | 0.367 | 1.612 | 2.185 | 3.002 | 1.5–2.5 g/Kg s.s. |

| K (g/Kg s.s.) | 7.919 | 3.288 | 5.871 | 8.241 | 6.150 | 5.5–8.5 g/Kg s.s. |

| pH | 6.7 | 8.1 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.5–7.3 (neutral) |

| Texture | fine clayey | clayey | fine clayey | fine clayey | fine clayey | 100–300 g/Kg |

| Pomace | Unit | Value | Soil Test Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOM | g/Kg | 915 | D.M. 13/09/99 SO GU n. 248 21/10/99 Met. VII.2 D.M. 25/03/02 |

| Total N | g/kg | 11.07 | D.M. 13/09/99 SO GU n. 248 21/10/99 Met. XIV.3 D.M. 25/03/02 |

| Total P | g/Kg | 2.567 | D.M. 13/09/99 SO GU n. 248 21/10/99 Met. XV.1 |

| Total K | g/Kg | 21.303 | UNI EN 13656:2004 + EPA 7000 B 2007 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manniello, C.; Statuto, D.; Di Pasquale, A.; Giuratrabocchetti, G.; Picuno, P. Planning the Flows of Residual Biomass Produced by Wineries for the Preservation of the Rural Landscape. Sustainability 2020, 12, 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030847

Manniello C, Statuto D, Di Pasquale A, Giuratrabocchetti G, Picuno P. Planning the Flows of Residual Biomass Produced by Wineries for the Preservation of the Rural Landscape. Sustainability. 2020; 12(3):847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030847

Chicago/Turabian StyleManniello, Canio, Dina Statuto, Andrea Di Pasquale, Gerardo Giuratrabocchetti, and Pietro Picuno. 2020. "Planning the Flows of Residual Biomass Produced by Wineries for the Preservation of the Rural Landscape" Sustainability 12, no. 3: 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030847

APA StyleManniello, C., Statuto, D., Di Pasquale, A., Giuratrabocchetti, G., & Picuno, P. (2020). Planning the Flows of Residual Biomass Produced by Wineries for the Preservation of the Rural Landscape. Sustainability, 12(3), 847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030847