1. Introduction

In 1992, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a book titled “A Guide to the Development of On-Site Sanitation,” highlighting the need for access to basic sanitation, such as the safe disposal of excreta, which is fundamentally important for the health and welfare of the community, including the control of its water supplies, vectors of disease, and housing conditions, among others. The publication also stressed that sanitation is of primary significance in human health as long as the lack of full sanitation services coverage represents a major problem for the integral development of human beings [

1,

2]. However, since this publication, the need for basic sanitation was one of the issues tackled in the United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2005 and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, which, in some cases, have been predicted to worsen as a result of the rapid population growth and being less considered for improvement and financial investment as compared to drinking water services [

1,

3,

4].

Across the globe, many people, especially those living in the most precarious socioeconomic situations in the peri-urban and rural areas, do not have access to sanitation [

5,

6]. Moreover, almost 1000 children die every day from diseases caused by poor water and sanitation conditions, which should be preventable. It is estimated that 2.4 billion people do not even have basic sanitation. In addition, approximately 80% of wastewater is discharged into water bodies without proper treatment [

7]. Many of these serious conditions have been encouraged by bad sanitation policies and projects, mainly because of government approaches that are not suited to the preferences of the users [

8], which result in the failure of the strategies implemented, or because of the use of conventional, old, and outdated technologies [

9,

10,

11]. High-ranking officials and decision-makers oftentimes do not include the users when selecting the technology or when implementing it in the sanitation system [

9,

11].

Worse, these approaches do less in preventing or improving the situation as they do not represent what users really need or prefer in the sanitation system [

12]. Thus, it is important for decision-makers to understand people’s culture and behavior, and to integrate the users in the formulation of strategies for implementation [

13,

14]. Practically, the sanitation systems must also be designed to be feasible, affordable, and user-friendly [

5,

6,

8]. In this regard, the identification of the users’ needs and preferences seems to be a central issue based on several authors’ reports showcasing the fact that the desired interventions were not holistic and did not meet user needs, and thus, could not be performed correctly [

6,

8,

10,

13,

15,

16,

17,

18]. In fact, a considerable number of research studies found several factors and indicators that seemed to correlate the choice of the best sanitation system with respect to certain users. These methods and compendium of indicators vary and require different types of approaches. Nevertheless, all the above authors had a common conclusion stating that a sanitation system should be developed with an approach that is user-centered, cannot generalize results, must link the user needs with resources found locally, must embrace a sociocultural approach, and must not be top–down [

6,

8,

10,

13,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Meanwhile, countries like Mexico aim to overcome the precarious conditions brought about by issues in water and sanitation and to achieve universal coverage of such services. In 2012, the Mexican government reformed the fourth article of its constitution to incorporate its citizens’ human rights to water and sanitation [

19], which infers a lot about its political legislators having understood the need to address the water crisis and sanitation precariousness in the locale [

20]. Although the 2018 National Water Commission of Mexico (CONAGUA) report stated that in 2015 about 92.8% of the population had access to sewerage and basic sanitation services and that the national coverage of public sewerage and septic tanks was 91.4%, these data referred mainly to the sewerage coverage, but not to wastewater collection and treatment (sanitation) [

21].

The End of Mission Statement of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation in México (2017) described that a large portion of the country’s population has access to very low-quality water and sanitation services or do not have both services at all [

22]. OXFAM, Oxford’s Committee for Famine Relief, also published a report depicting the strong likelihood of deficient water services with poverty, as portrayed in the inequality gap in Mexico where the lower-income citizens have to pay more but receive lower-quality services than the high-income users [

23]. Such a situation is said to be more complicated in the southern states of Mexico, where the poverty levels are four times higher than the national average and risk factors, such as undernourishment, polluted water sources, poor sanitation services, and air pollution, are likely to increase child mortality by eight times more than in northern Mexico [

24,

25].

The economy of Chiapas, the country’s poorest state, depends on primary exports like unroasted coffee, bananas, and raw sugar, which make it a state with no economic diversification [

26,

27]. About 70% of its 5,217,908 inhabitants do not have access to drinking water and sanitation, whereas approximately only 26% of the homes were installed with piped water [

28,

29,

30]. Thus, the region has a high economic privatization index, a high vulnerability to climate phenomena, and one of the biggest indigenous populations in the country [

28,

29] that are most affected by the inequality in the provision of water and sanitation services [

11,

23]. Additionally, all water streams in the area are polluted as most of the wastewater running throughout the region remains untreated [

30,

31].

Considering the scenarios above, it is imperative for policymakers, decision-makers, researchers, and technical sanitation professionals to be equipped with an instrument that allows the identification of indicators to determine user preferences as input for the selection and creation of sanitation systems, and thus, ensure improvement in the quality of life of the users as well as in the utilization of the systems for implementation. It is essential that the solutions be developed parallel to the context and environment of the locality, should be affordable to users and can be used correctly and consistently to improve health [

32].

This study has a two-fold objective. First, it aims to develop an approach to identify the variables and indicators that allow the determination of user preferences required in the selection and implementation of more holistic sanitation strategies, technologies, systems, and services. Second, it aims to apply such an approach in the rural communities of the state of Chiapas in Mexico to determine the user preferences needed for the selection of appropriate sanitation systems. The effectiveness of the proposed approach in identifying the user preferences is discussed herein, which makes it feasible as an intrinsic part of the design, planning, and implementation process in leading rural communities toward achieving sustainability and SDGs on universal basic sanitation.

2. Methodology

2.1. Preparation of the Approach to Identify the Variables and Indicators

An exhaustive literature review of specialized academic and scientific websites (Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Wiley Journals, Scielo, among others) was conducted to identify the required social variables and indicators to determine user preferences as input for the selection and implementation of more holistic sanitation strategies, technologies, systems, and services. The social variables were prepared by grouping them in a matrix with respect to:

- i)

the recurrence of these variables across different studies (saturation);

- ii)

the influence of these variables;

- iii)

and, their importance in describing and identifying the needs and desires of the users.

To simplify the data analyses, the indicators were defined based on the variables selected.

As soon as the variables and indicators were identified, a field survey protocol was prepared in three sections, as follows:

Section a of the survey was structured for the collection of the socioeconomic information of the users, including their age, gender, school level, occupation, number of family members, access to basic sanitation, type of sanitation service, willingness to change the actual systems, weekly income, capacity of investment, and community location;

Section b evaluates the importance of sanitation with respect to other services such as piped or potable water, electricity, sewerage, mobile phone, internet, and television; and

Section c gathers information related to the users’ preferences and is divided into 10 subsections that correspond to the rest of the indicators: technical, ease, cost, esthetics, surroundings, user, peer influence, hygiene, social interactions, and environment.

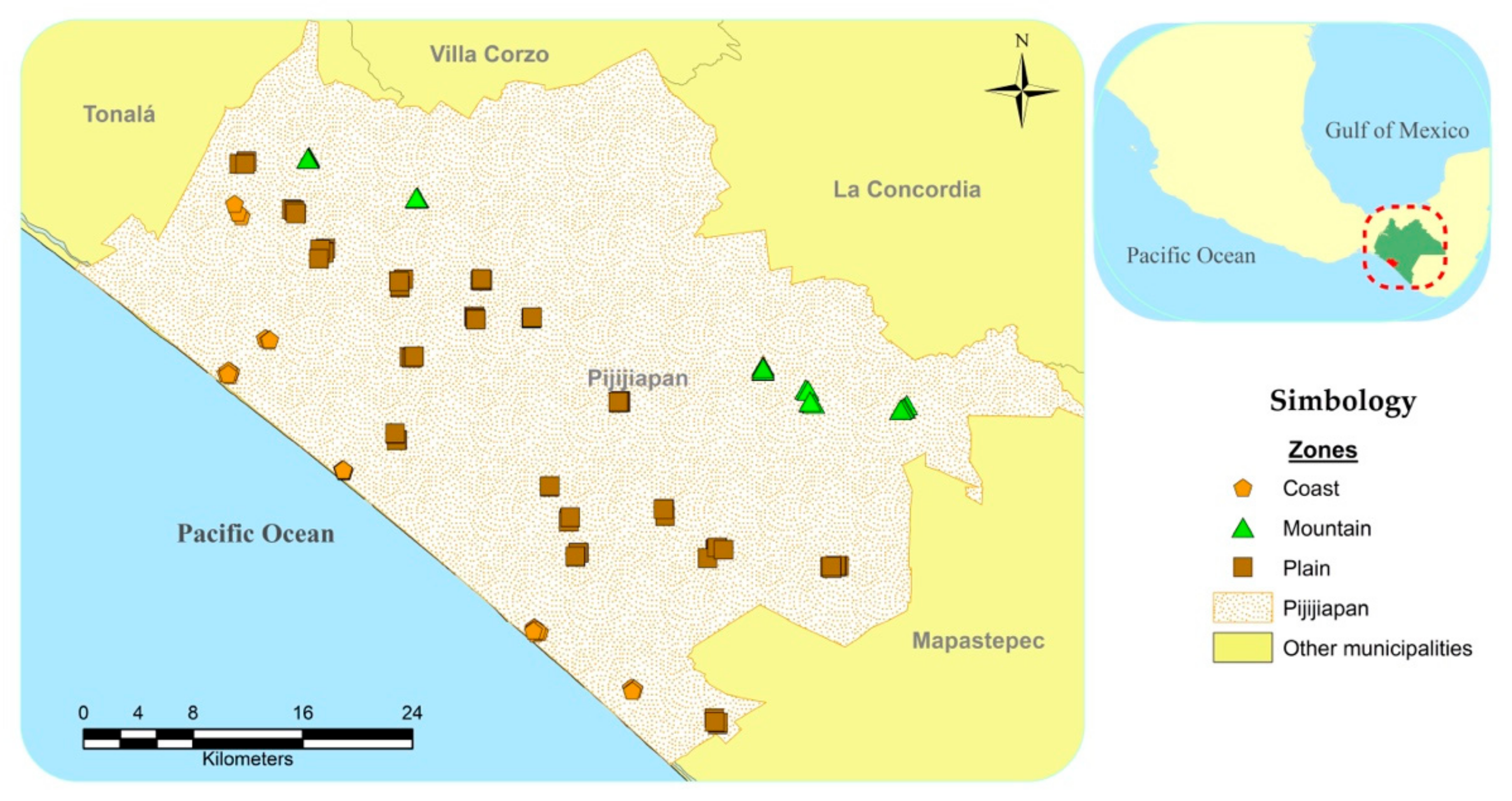

2.2. Application of the Approach in Rural Localities of Chiapas

A field survey was conducted in the rural communities of Pijijiapan, state of Chiapas, Mexico, targeted to users and decision-makers 18 years and older. The survey for the users was different from that for the decision-makers, where the aim was to understand the differences and the values each group contributes to the sanitation service. The municipality was chosen because of its level of poverty and illiteracy. For the survey, sample size was estimated based on the total number of communities (788) in the municipality using the protocol described in [

33]. Subsequently, the Pareto principle was employed as it was deemed suitable to represent the largest section of the population. Communities with more than 100 inhabitants and representing 80% of the population were grouped, and then a new sample size was calculated to set the number of interviews to be applied. The information was collected by means of mobile phones and an app named EpiCollect+ that allows data storage on the cloud.

Respondents (users) were selected by means of a snowball-type sampling [

34], whereas decision-makers were authorities or leaders of the communities. The data collected were analyzed and processed using Pearson’s chi-square tests for associations, given a significance level of α = 5%. Relationships between the indicators were analyzed and described to identify user preferences. Two-proportion and Pearson’s chi-square tests were also conducted for some specific users and decision-makers’ answers to identify any similarities or differences in their responses and to disclose if authorities are aware of the users’ interests in and needs of sanitation. Issues selected for the comparison included the preference between sanitation and other services, willingness to change, location, management, privacy, and construction material.

4. Discussion

The SDGs on sanitation has pinpointed the current need for developing ecological and conventional sanitation technologies in close collaboration with the users [

13]. Thus, new holistic approaches have been and are being designed to evaluate users’ preferences on sanitation systems to ensure their success. Unfortunately, only a handful of researchers have undertaken the task of analyzing and understanding user preferences, so the task remains large. In addition, most of the current approaches focus on one or two aspects of sanitation, such as usage or ownership, and cost or technical features [

8], whereas some have a significant number of variables [

6]. Moreover, researchers such as Simiyu [

18] and Conradin [

50] have evaluated technologies where they were already implemented, and as Nawab et al. [

13] suggested, it is possible and probably better to conduct the evaluation before the design and implementation based on user preferences, to improve and maybe ensure the acceptance of such systems. Until now, initiatives to address the lack of basic sanitation worldwide have ignored the human aspect, and the approaches do not represent what users need or prefer in a sanitation system [

12]. This study incorporated the analysis of user preferences as part of the design, planning, and implementation process of a sanitation system to achieve universal basic sanitation coverage. Therefore, user preferences, along with the technical components that make a sanitation system efficient, can lead to ensuring the correct performance and appropriation of sanitation technologies [

8,

51].

In this study as well, localities were found to have less access to improved sanitation services and poorer associated behaviors. Their current sanitation system keeps nutrients out of the agroecological cycle, which may contribute to significant environmental impacts [

13]. The system also provides a breeding ground for harmful fauna such as mosquitoes, diffusion of bad odor, and groundwater contamination, which are health risk factors for the possible transmission of contagious and serious illnesses such as malaria, Zika, chikungunya, and dengue [

52,

53]. When a sanitation system has an impact on health (sanitary risks, transmission of diseases, and malnutrition), environment (water pollution and groundwater over-extraction), well-being (safety, dignity, and gender equality), and the economy (cost of health and environmental degradation) of communities, it consequently affects the capacity of an area for sustainable development [

52]. According to Imbach [

54], “Sustainable development is the permanent process towards the satisfaction of all fundamental human needs without irreversible degradation of the environment.” In this context, fundamental human needs are needs that must be satisfied to achieve a dignified life. These are related to the individual, the surroundings, and a productive life. People living in rural and poor populations need motivation to satisfy these needs, being usually more concerned about their daily sources of food, water, shelter, and security rather than sanitation [

13].

Interestingly, in 2015, Mexico claimed that it has “achieved” its MDG sanitation target, with 85% of its population (urban and rural) having access to improved sanitation services (however, this figure was more pertinent to sewerage access and not specifically to sanitation) [

21]. Comparing the official figures provided by CONAGUA (National Water Commission of Mexico) and the United Nations (

Table 6), it is no doubt that Mexico has achieved 92.8% of national sewerage coverage. However, only 45.54% of the population has been using safely managed sanitation. Thus, the technical implementation (coverage) of the systems was not equal to the percentage of usage. As a matter of fact, in the specific case of rural areas, the national sewerage coverage was barely 77.5%, while in Chiapas specifically, it was 68.9%, with no data available on the proportion of people using a safely managed sanitation system.

The findings describe that the situation in rural settlements remains far from being sustainable and dignifying. Thus, it is imperative to improve sanitation facilities and increase awareness regarding its importance in reducing health risks and poverty and supporting socioeconomic development [

52]. With the urgency to achieve sustainable development through MDGs, implementers have prioritized the construction of sanitation systems over ensuring their use and user acceptance [

3]. Moreover, faulty designs, inadequate technical knowledge, and unsuitable technologies [

51,

57,

58] are important aspects to consider to understand why systems fail to be adequate. Of equal importance are social values and cultural variations that influence the type of technology appropriate for a specific community context [

57]. When understanding user needs, experiences, and preferences, it is important to comprehend what current choices are available and what treatment methods can be used [

32].

The study results show very clearly that in rural areas where people are marginalized, there is a need for basic services with a technology adapted on a local basis, meeting payment for these services, and maintenance possibilities. It is also important to consider the user preferences associated with the structural and functional parts of the system, payment capacity associated with the implementation, use, and construction of the system, and protection users need from the environment that surrounds them. Cost is a crucial factor for the success and broad implementation of a system. For instance, a higher cost can influence the decision of the users to accept or refuse the implementation and use of a system [

50,

59]. Indeed, affordability is one of the most defiant constraints. If the technology is not affordable for the majority of potential users, then it is not suitable for the circumstances [

57,

60].

In some cases, preferences such as the esthetics of a system could be an important issue. However, in poor rural areas where people are marginalized, the preference is commonly basic services. In these areas, the most important element is the sanitation service itself, where the appearance of the toilet or the system is not a must for the community to accept, as opposed to the assertion of [

17] “where sanitation facilities are lacking or not functional, a pleasant-looking and functional toilet is a source of pride.” Meanwhile, shared systems can be a source of community conflicts. For instance, when users do not maintain hygiene in the toilet vicinity, then unsanitary conditions may initiate failure on the appropriation of the system and subsequently lacerate community relationships and complicate the optimal management of the system, maintenance, repairs, waste management, profits, cleaning, etc. Depending on the social capital, in some cases, users would not want to avoid creating problems [

61], which justifies why they would rather have private systems than shared. Furthermore, financial barriers can represent a significant challenge in terms of the willingness of users to pay. Although they want to pay, saving, or collecting money may be difficult for them. Another issue is the lack of trust between the community or family members when the utilization of money is involved [

61]. In the area of study, the majority simply could not afford sanitation charges. Thus, the government is not able to settle fees to the service, first, because it has no financial and infrastructural capacity to give basic sanitation services and second, because of the lack of trust in monetary management [

3]. As a result, improvements in sanitation are difficult to achieve in the area.

In another perspective, focusing only on user preferences is not completely accurate. In this study, people in the locale did not show any interest in and awareness of the environmental and health impacts of poor sanitation, presumably because they were not fully informed of the negative externalities and implications of the lack of quality sanitation services on health and hygiene. Lack of awareness of this aspect is often related to poor educational standards. Nevertheless, it has been shown that poor and illiterate people have the potential and capacity to make good choices if they are given the opportunity to be involved from the start to the conclusion of sanitation projects [

13]. Awareness is crucial in introducing good interventions and communicating the importance of sanitation to ensure a healthy community [

62]. In other words, being active in the development of sanitation projects or at least knowing a little more about sanitation can benefit the system and the knowledge of people as individuals and as a community.

Furthermore, the government plays an important role in achieving full coverage of sanitation services. In the past, it was not a priority, and there were deliberate actions that permanently disrupted a sanitation system’s use, maintenance, and performance, thereby creating mistrust and expectations from people for free services from the government, even when they are not poor [

3,

63]. Likewise, direct user and stakeholder participation, as well as empowerment by intermediate-level organizations, can provide an avenue to identify the needs of the community [

57,

64]. This implies that current and future interventions in the design, selection, development, and monitoring of technologies and the subsequent provision of sanitation services should involve community decision-makers who understand people’s culture and behavior, to develop strategies with users as part of the process and to implement feasible, affordable, and user-accepted sanitation systems [

6,

7,

9,

14,

15].

Finally, although the focus of the study was on rural communities in Mexico, this does not limit the application and analysis of sanitation in other countries having the same problems related to basic sanitation, as those observed in

Table 7, with a low proportion of the population using safe sanitation services.

5. Conclusions

A comprehensive approach was proposed to identify the variables and indicators that allow the integration of human issues (user preferences) in the selection and creation of more holistic sanitation strategies, technologies, systems, and services. The proposed approach was shown to be effective in the identification of user preferences and, therefore, is recommended to be an intrinsic part of the design, planning, and implementation process to lead rural communities to achieve sustainability and SDGs on universal basic sanitation.

As it was necessary to understand how culture, preferences, practices, and socioeconomic conditions directly affect the possibilities for users to gain access to basic sustainable sanitation services, the approach was assessed in the rural communities of Chiapas, the poorest state in Mexico. The results showed that sanitation is an important service for the users. Nevertheless, if there is a lack of other services, the concern toward sanitation could be affected by the priority to meet daily needs, such as food and shelter.

With regard to preferences linked to the system’s technical features, its esthetics, costs, and socioeconomic-related aspects were the most important to be considered for the provision of basic sanitation. The most important preferences of the users were privacy and protection proportioned by the system, the type of material for the toilet and the floor, and the costs of construction and maintenance. These preferences need to be an intrinsic part of the design, planning, and implementation processes to lead rural communities toward sustainability and to achieve SDGs of universal basic sanitation coverage. These elements, along with awareness of sanitation and government support, could help increase the appropriation and success in the use and implementation of basic sanitation services, as well as help recognize the limitations of certain types of sanitation systems and technologies before they are implemented. It is practical to say that leading rural communities to be sustainable remains a long and arduous task, but sanitation is not an isolated topic, as cultural, political, and economic forces are driving it, which means that it must be within a holistic framework that takes into account all the resources available in the community. The priority should be to design basic sanitation services based on user preferences.