Starting a Participative Approach to Develop Local Green Infrastructure; from Boundary Concept to Collective Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Problem Statement

- the different perceptions of the impact of GI on management decisions and the use and value of private land,

- the contrasting interests of nature conservationists, farmers, hunters, anglers or foresters and the mutual frictions this brings about;

- the regulation of (land) use in designated areas; i.e., the issue of exclusive or joint use of designated land and the uncertainties this creates;

- the lack of a clear and effective communication strategy, especially between members and officials of the regional government on the one hand and local stakeholders or the general public on the other, which results in the failure of a fruitful participation strategy.

- the weak coordination capacity of different policy domains and departments, as well as the bad tuning of procedures and timing of different policy levels;

- the lack of political agreement between political parties involved in the allocation of the ecological network.

- the indistinctness about the consequences of designation for economic activities and the required compensation if any;

- the uncertainty about acquisition and management costs of GI and the availability of guaranteed funds.

- the incomplete knowledge about the nature targets of GI, the management practices necessary to reach these goals, and the consequences this has for formulating any alternative arrangements that may facilitate joint land use of designated land.

1.2. Looking for a New Approach towards Integration of Objectives: The Gobelin Project

1.3. State of the Art

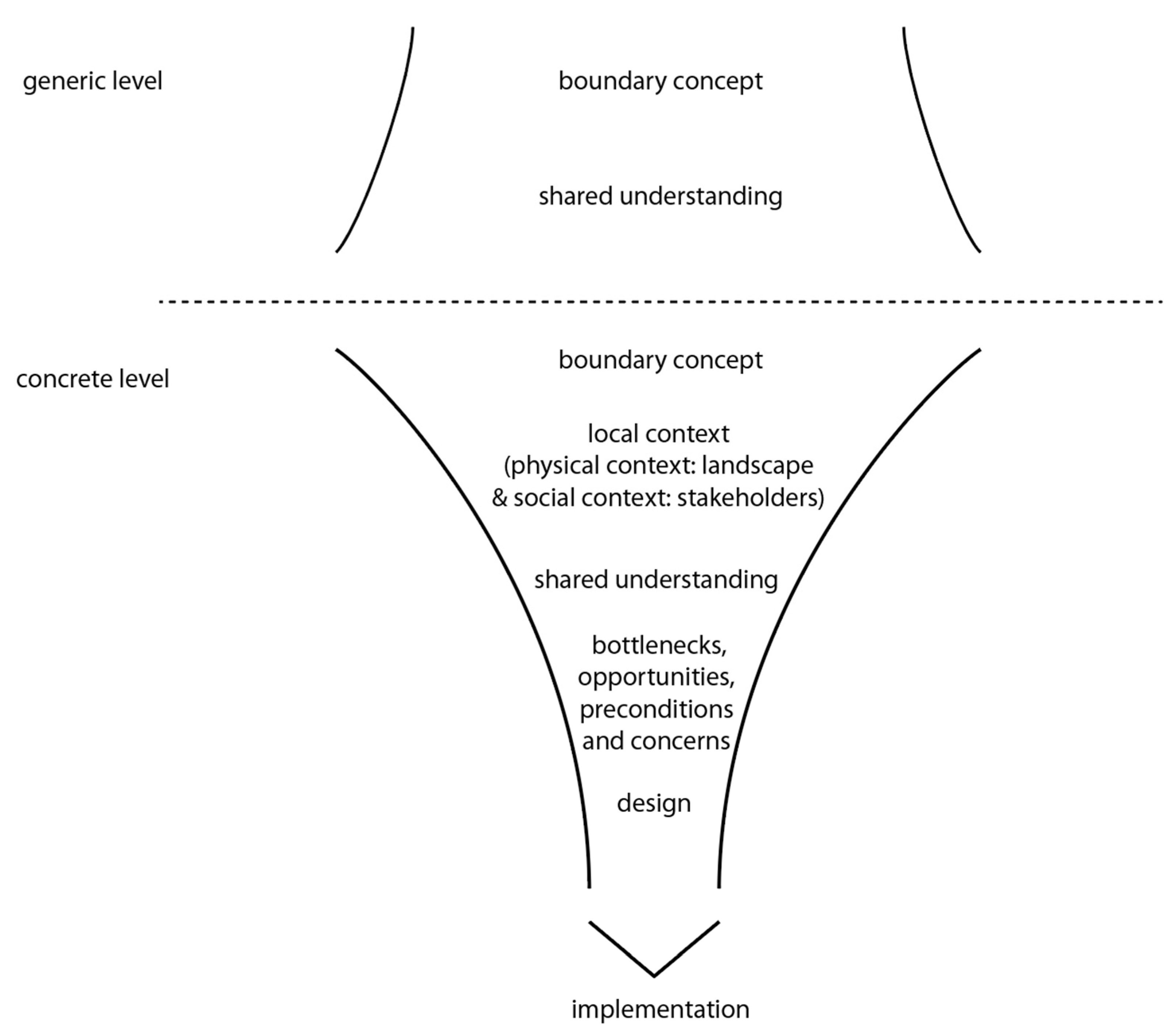

1.3.1. Boundary Concepts and a Common Language

1.3.2. Multi-Stakeholder Process

1.3.3. Role of the Design(er)

2. Methodological Approach

2.1. Case Selection

- (1)

- local coordinating actors have the intention of planning a GI in their mandate area so that follow-up is assured after the Gobelin-project is finished;

- (2)

- local coordinating actors express an explicit policy interest for GI and have adequate time to invest in the project;

- (3)

- local coordinating actors are open to stakeholder participation;

- (4)

- case study areas have the potential for habitat improvement and ecosystem service delivery optimization.

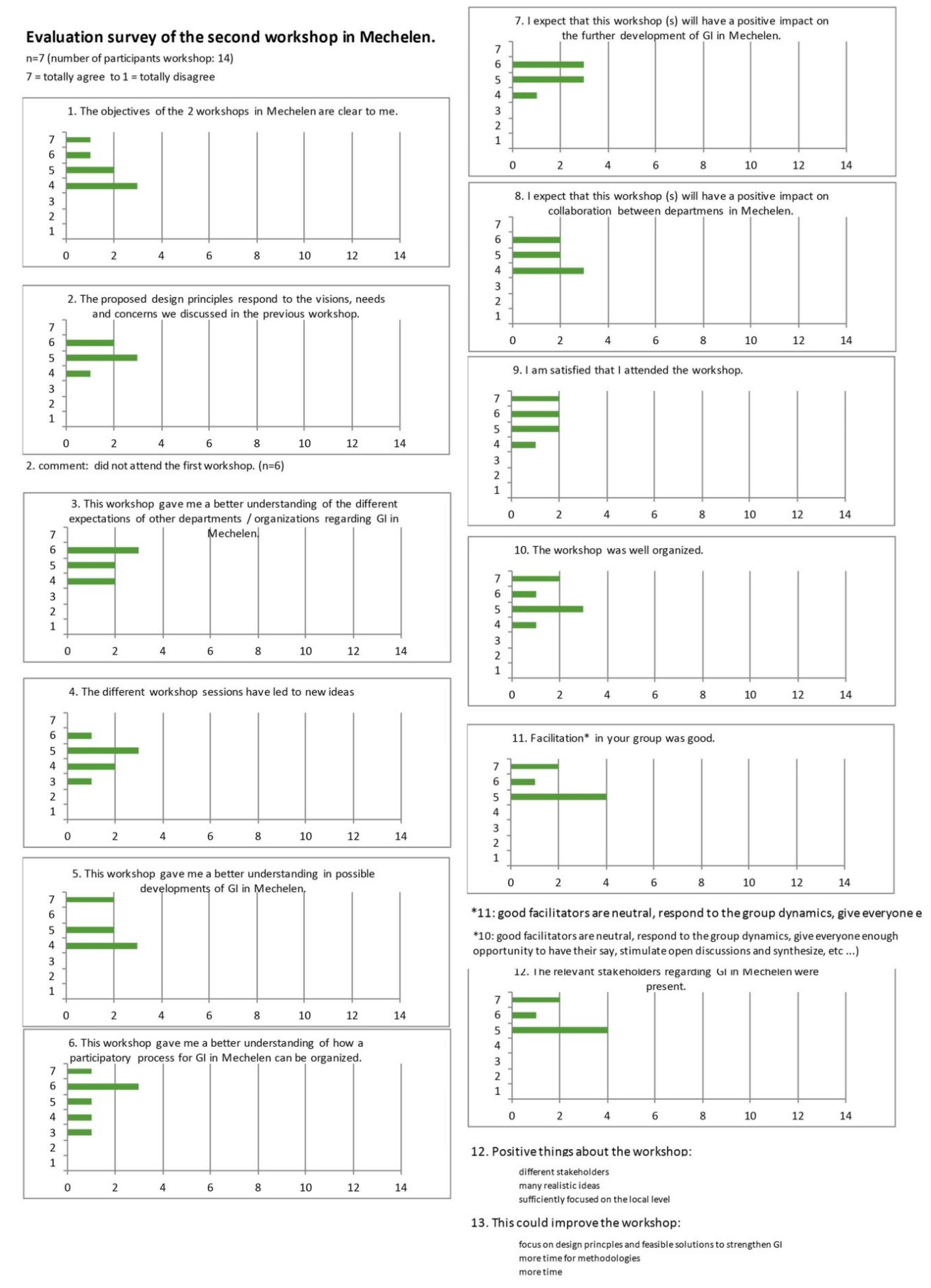

2.1.1. Mechelen Case

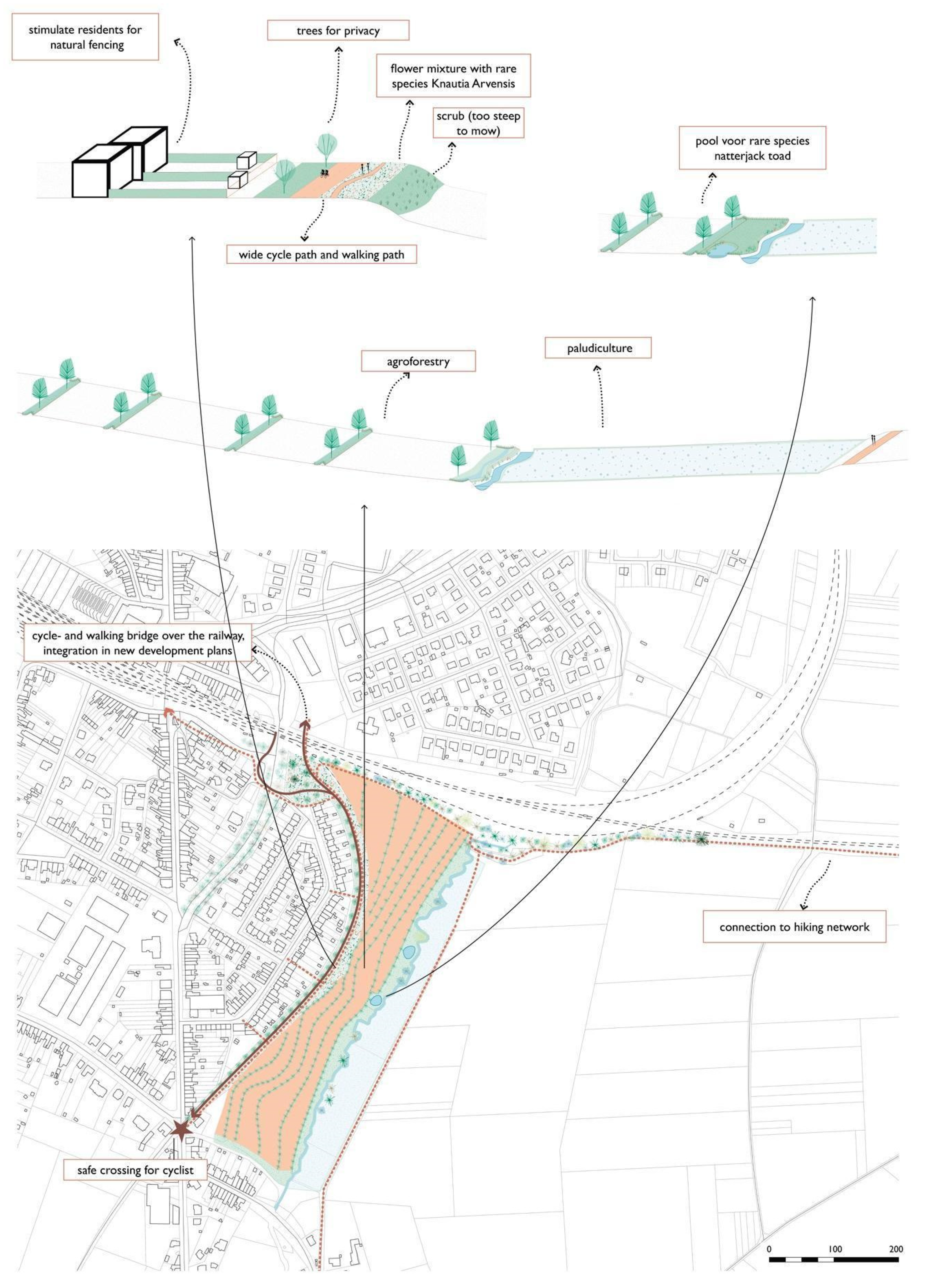

2.1.2. Landen Case

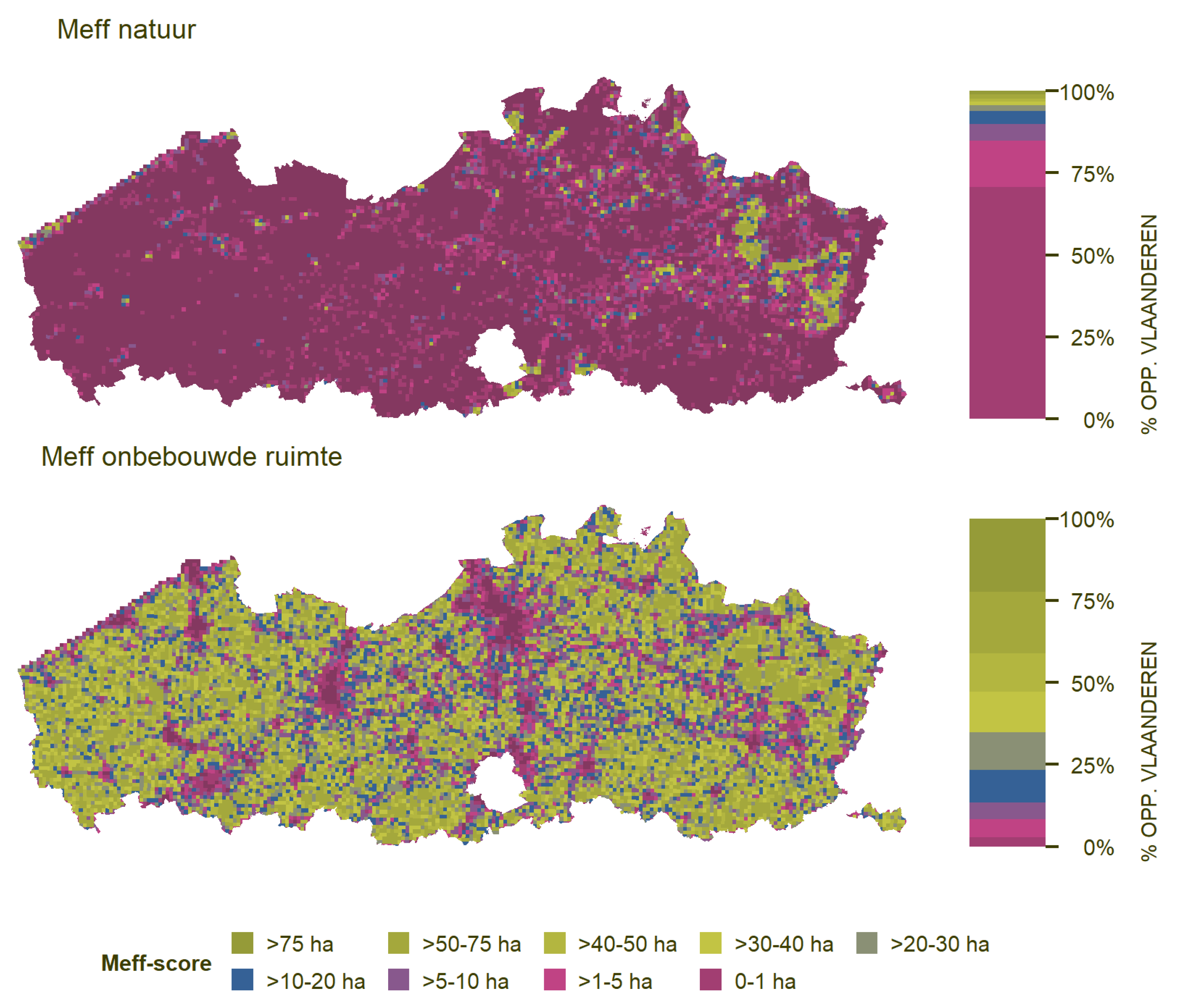

2.2. Roadmap

- (1)

- In the preparatory phase, consultations of the project with the local coordinating actors were held to identify additional relevant stakeholders and to analyze the relevant local policy context. Additionally, through a field visit, the researchers became familiar with the study area.

- (2)

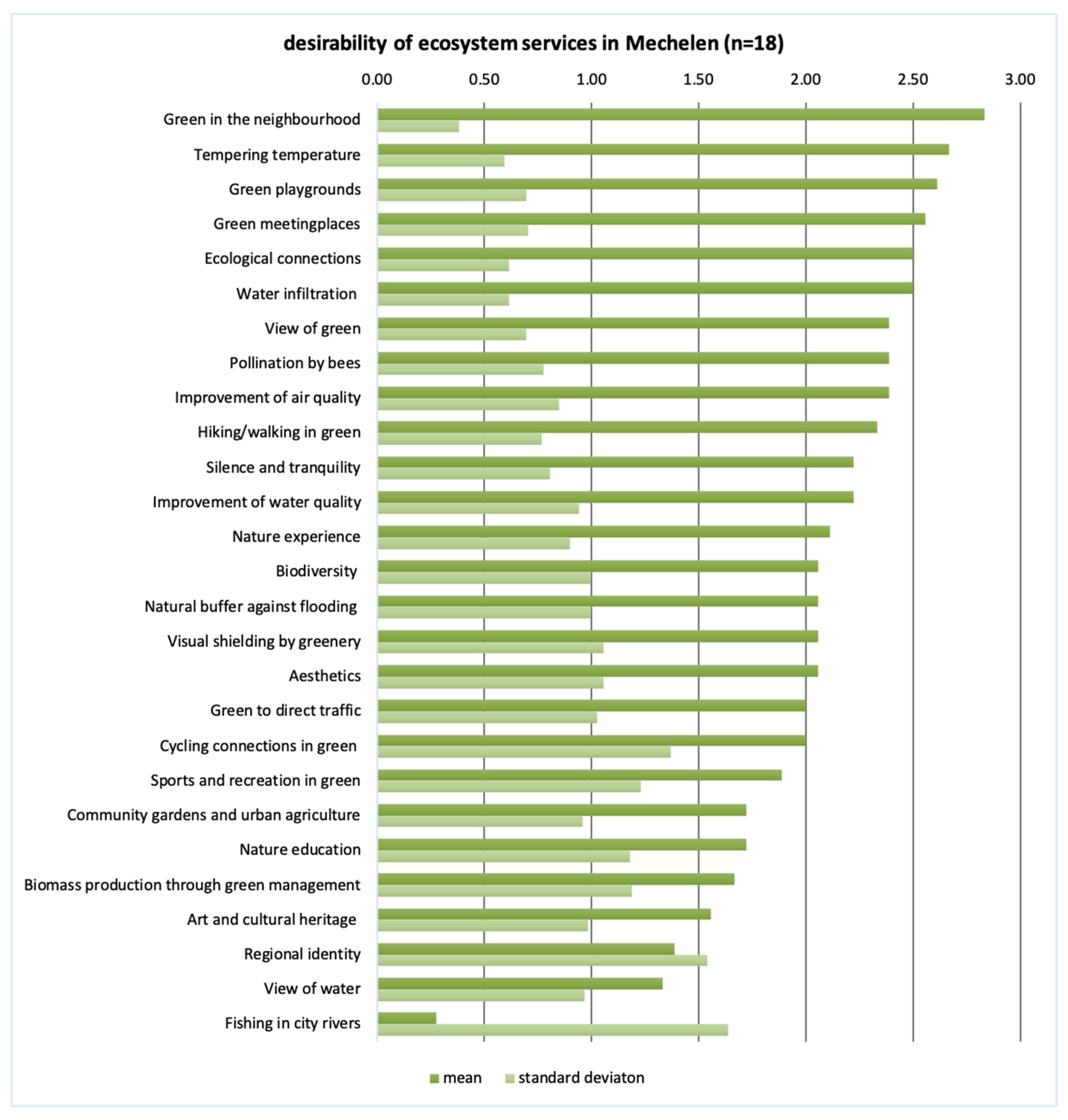

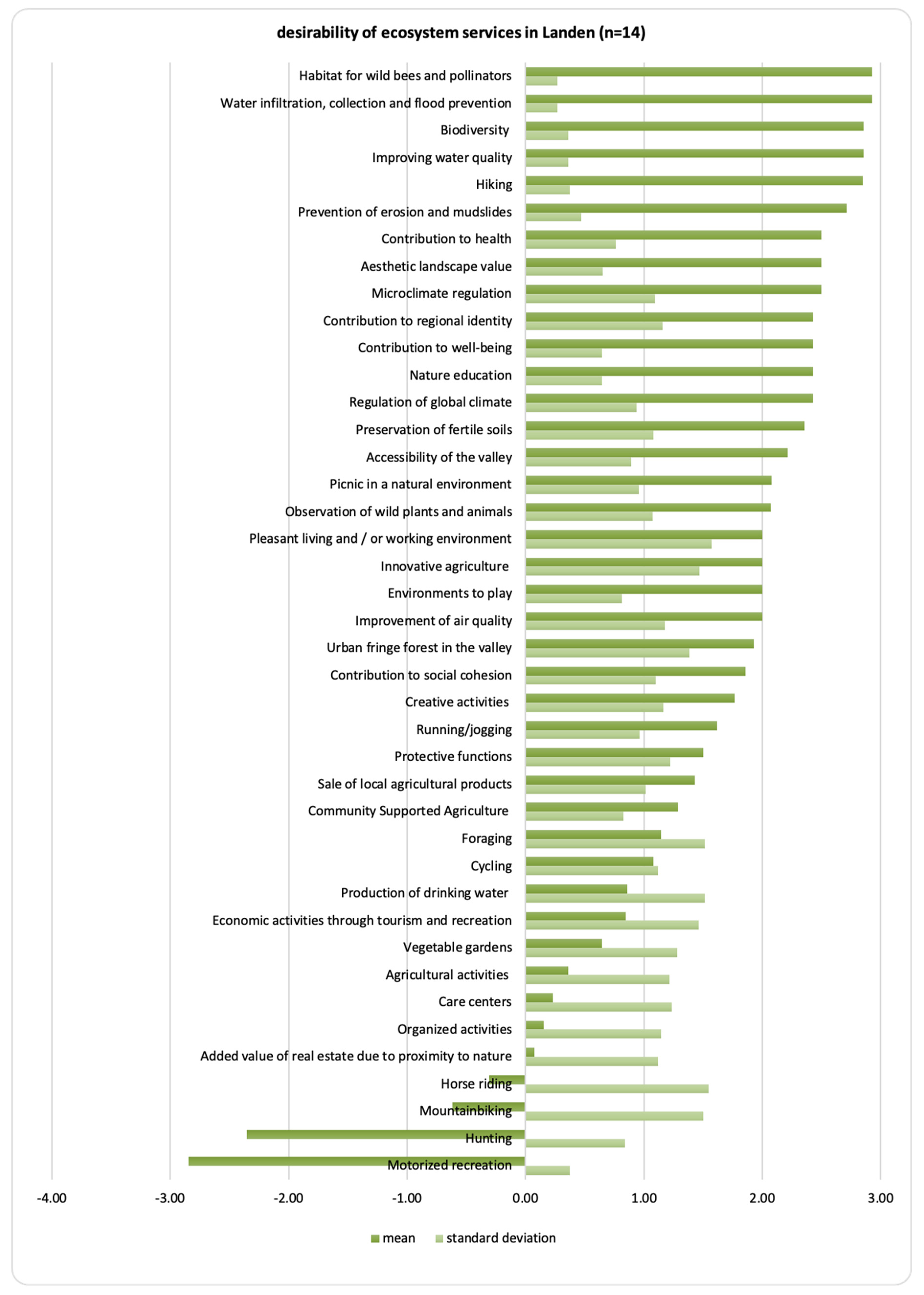

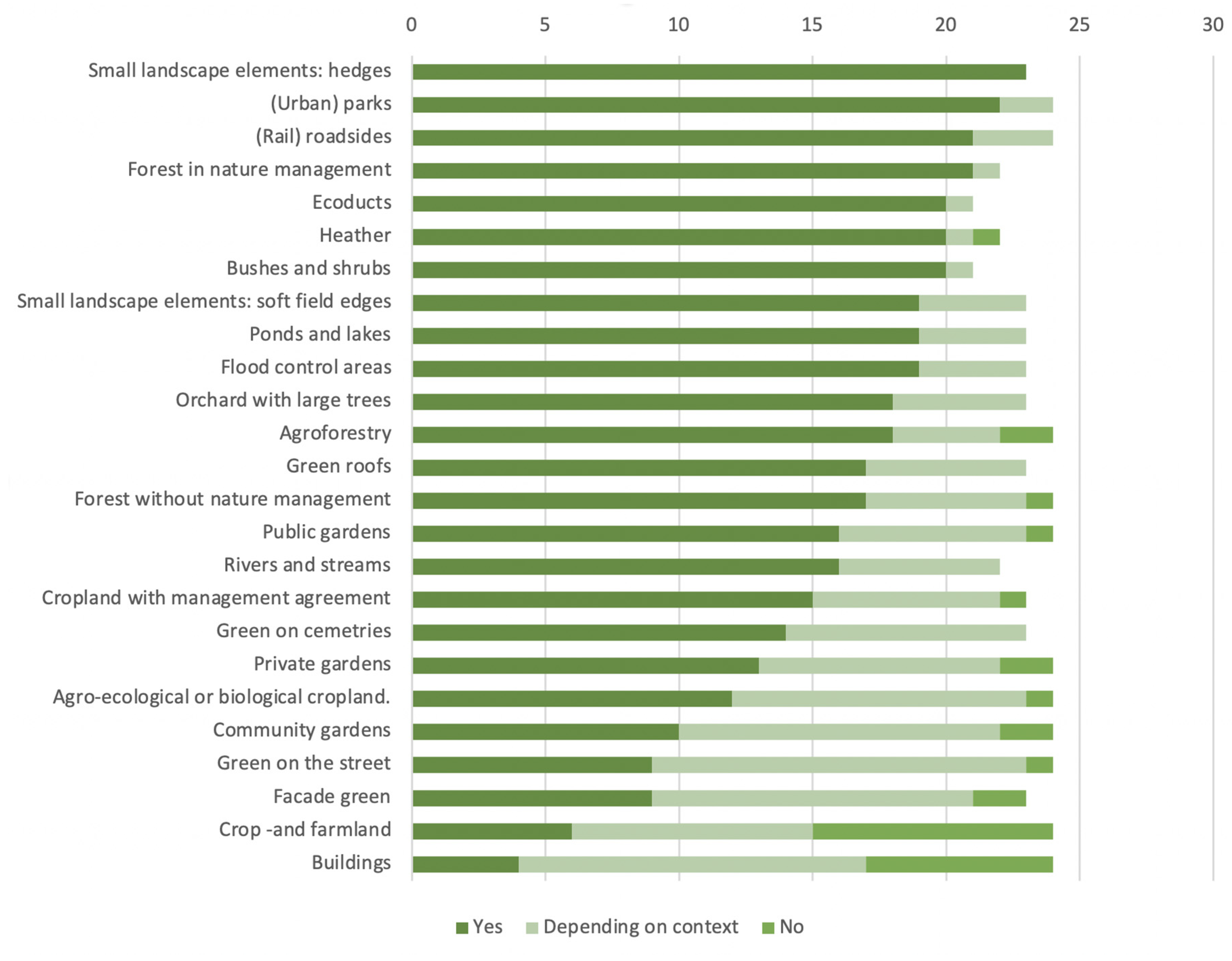

- Successively, an online ecosystem services scan was carried out. This online scan was sent to the invitees of the first workshop (see step 3). The goal of the scan was to detect the desired functions (ecosystem services) for the GI in the planning area. For this individual valuation, a 7-point Likert scale was used. Participants were asked to score a list of potential functions from ‘very undesirable’ to ‘very desirable’. The list of functions was based on policy documents, scientific overviews, and checked by the local coordinating actors [45,46]. (See Figure A1 and Figure A2 in Appendix A)

- (3)

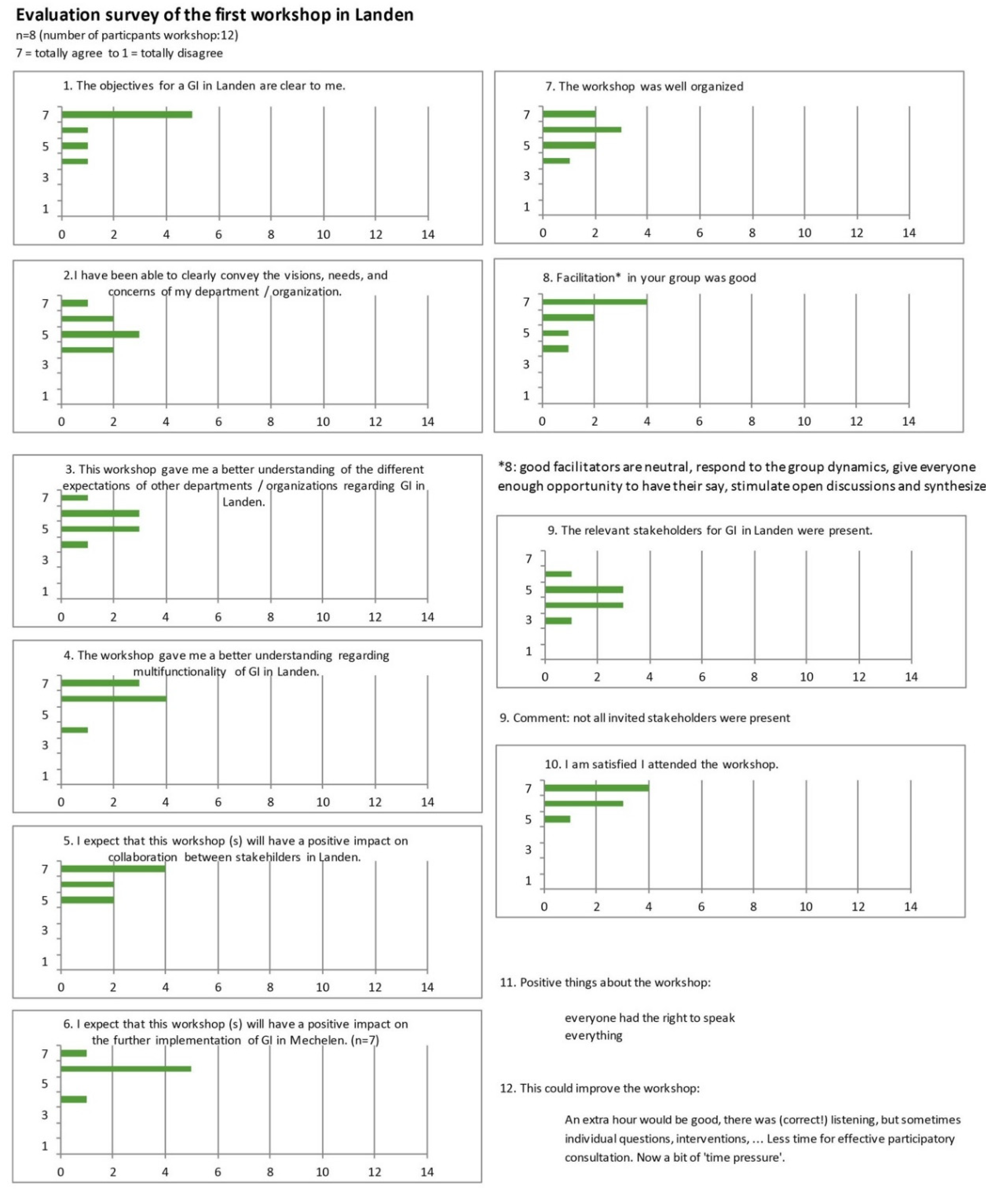

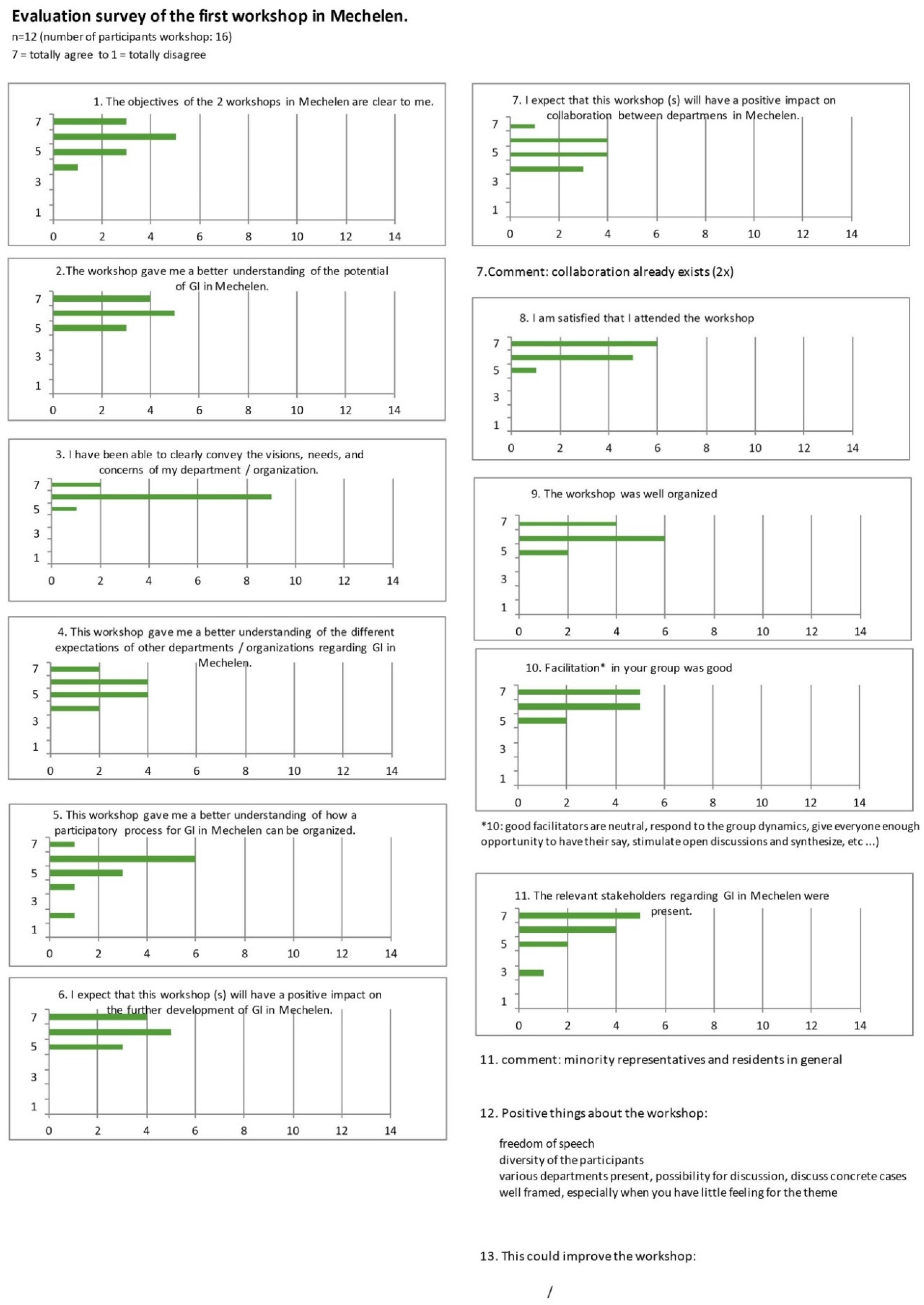

- During the first workshop, challenges, opportunities, and ideas were discussed. Representatives of different sectors, interest groups, public administrations, and local councils were invited to the workshops. First, the results of step 2 were discussed and validated. Afterward, discussions in small groups (5–8 people) detected bottlenecks, opportunities, preconditions, and concerns of the planned GI. Finally, participants were asked to Identify key institutions, organizations, and persons for project-oriented coalitions, required for the realization of the planned GI.

- (4)

- In the design phase, design drawings of possible GI solutions were made. Based on the information gathered during workshop 1, the field visit and document analysis, one or more design proposals were drafted for the area. The expressed desired functions, as well as the identified bottlenecks, opportunities, preconditions, and concerns were taken into account as much as possible.

- (5)

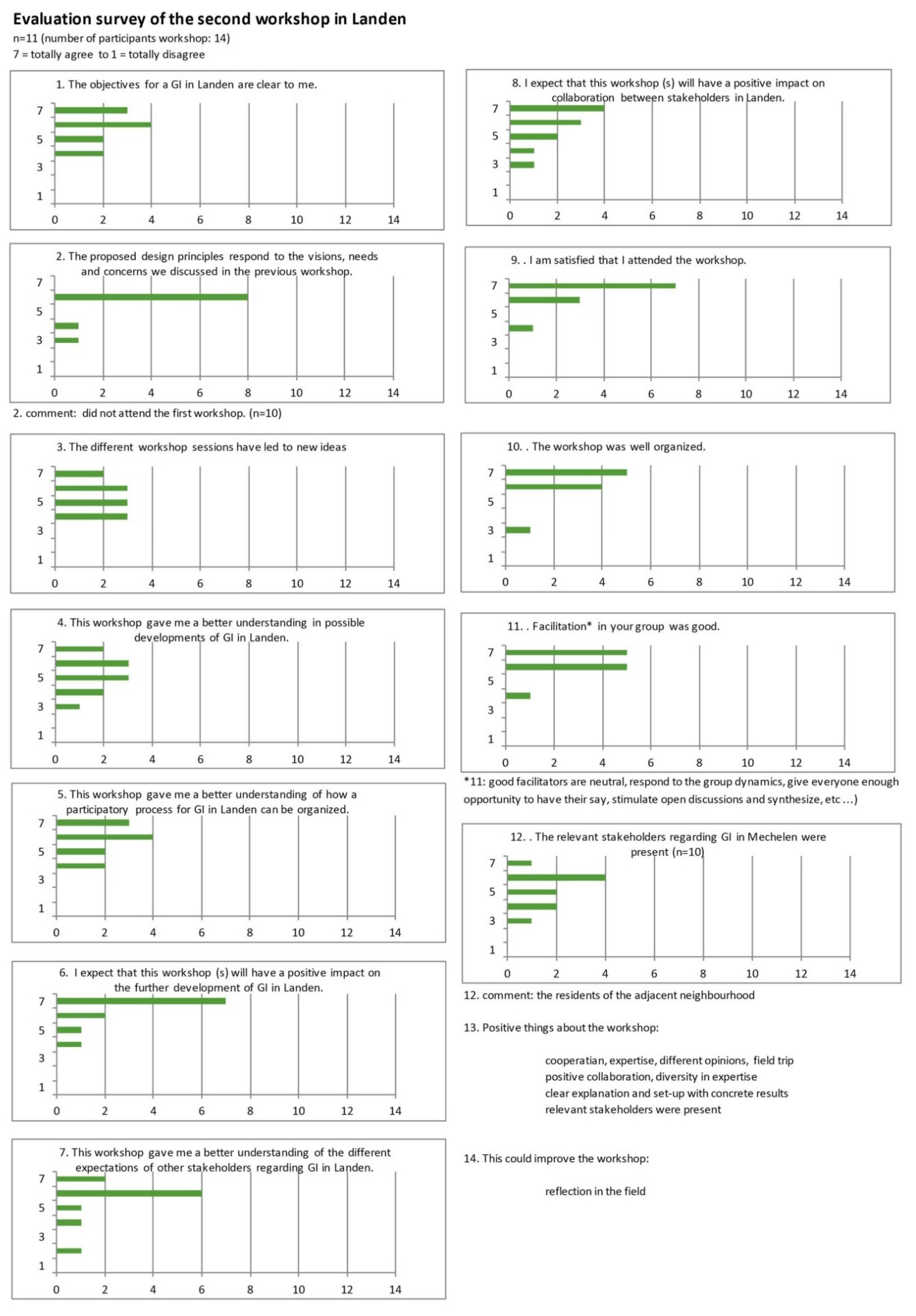

- In the second workshop, the design proposals were presented and evaluated. Several alternative design scenarios were used to trigger a debate between the participants. The participants gave feedback on the different design scenarios. Due to the rich visualizations of the design research, a fruitful discussion about possible strategic solutions was conducted in a targeted manner. In the Landen case, an ‘ecosystem services proofing’ of the design was carried out during this workshop. An ecosystem services proofing is an estimation of the impact of the design on the desired functions that were identified during step 2. This was done through discussions in response to the question “To what extent will the proposed design influence desired functions (identified in step 2)?” Participants were asked to agree on a score on a 7-point Likert scale. This score was compared with the scores of step 2.

3. Results

3.1. Boundary Concept and Common Language

3.2. Multi-Stakeholder Process

3.3. Design Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- European Environment Agency. The European Environment—State and Outlook 2020. Knowledge for Transition to a Sustainable Europe; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsevell, M.; Fisher, M.; Boeraeve, F.; Jacobs, S.; Liekens, I.; Marques, A.; Molnár, Z.; Osuchova, J.; Shkaruba, A.; Whittingham, M.; et al. Setting the Scene, the Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Europe and Central Asia; Secretariat of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pisman, A.; Vanacker, S.; Willems, P.; Engelen, G.; Poelmans, L. Een Ruimtelijke Analyse Van Vlaanderen; Ruimte Rapport Vlaanderen (RURA); OMGEVING: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; ISBN 9789040303975. [Google Scholar]

- Country Fiche ‘Territorial Patterns and Relations in Belgium’. Available online: www.espon.eu/belgium (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Schneiders, A.; Alaerts, K.; Michels, H.; Stevens, M.; Van Gossum, P.; Van Reeth, W.; Vught, I. Toestand Van De Natuur in Vlaanderen; Natuur Rapport 2020; Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, J.A.; Soukup, T.; Schwick, C.; Madriñán, L.F.; Kienast, F. Landscape fragmentation in Europe; Joint EEA-FOEN Report No. 2; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintle, B.A.; Kujala, H.; Whitehead, A.; Cameron, A.; Veloz, S.; Kukkala, A.; Moilanen, A.; Gordon, A.; Lentini, P.E.; Cadenhead, N.C.; et al. Global synthesis of conservation studies reveals the importance of small habitat patches for biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés, A.; Lenoir, J.; De Frenne, P.; Andrieu, E.; Brunet, J.; Chabrerie, O.; Cousins, S.A.; Deconchat, M.; De Smedt, P.; Diekmann, M.; et al. High ecosystem service delivery potential of small woodlands in agricultural landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2020, 57, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongman, H.G.R.; Pungetti, G. Ecological Networks and Greenways: Concept, Design, Implementation; Jongman, H.G.R., Pungetti, G., Eds.; Cambridge Studies in Landscape Ecology: Cambridge, UK, 2004.

- Mell, I.C. Green Infrastructure: Concepts, Perceptions and Its Use in Spatial Planning; Newcastle University: Newcastle, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions (COM/2013/0249 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaamse Regering. Beleidsplan Ruimte Vlaanderen, Strategische Visie; Departement Omgeving: Brussel, Belgium, 2018.

- Kelchtermans, T. De Groene hoofdstructuur van Vlaanderen, Richtnota. In Ministerie Van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, AMINAL; Departement Leefmilieu en Infrastructuur: Brussel, Belgium, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- De Blust, G.; Kuijken, E.; Paelinx, D. The green main structure for Flanders. Perspect. Ecol. Netw. Eur. Cent. Nat. Conserv. ECNC Publ. Ser. Man Nat. 1996, 1, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaams Ecologisch Netwerk (VEN) en Integraal Verwevings-en Ondersteunend Netwerk (IVON). Available online: https://www.inbo.be/nl/vlaams-ecologisch-netwerk-ven-en-integraal-verwevings-en-ondersteunend-netwerk-ivon (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- First National Report of Belgium to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Belgian Clearing-House Mechanism, Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: http://bch-cbd.naturalsciences.be/belgium/implementation/documents/nationalreports/natiorep1/flemish.html (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Vriens, L.; Demolder, H.; Adriaens, T.; Bayens, R.; Boone, N.; De Beck, L.; De Keersmaeker, L.; De Knijf, G.; De Smet, L.; Devisscher, S.; et al. Toestand Van de Natuur in Vlaanderen. Cijfers Voor het Beleid; Natuurindicatoren: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, D. Natuurbeleid in Vlaanderen. Ph.D. Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Verheyden, W.; Turkelboom, F.; De Blust, G.; Smets, J. Groenblauwe Netwerken in Vlaanderen—Van Breed Concept Naar Uitvoering op het Terrein; Gobelin Rapport No. 1; Instituut voor Natuur- en Bosonderzoek: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Planning Policy Framework—Policy Paper. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-planning-policy-framework--2 (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Advice and Guidance—Scottish Planning Policy. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-planning-policy/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Di Marino, M.; Tiitu, M.; Lapintie, K.; Viinikka, A.; Kopperoinen, L. Integrating green infrastructure and ecosystem services in land use planning. Results from two Finnish case studies. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 643–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green Infrastructure Programs. Available online: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/climate-change/green-infrastructure-programs/19780 (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Jerome, G.; Sinnett, D.; Burgess, S.; Calvert, T.; Mortlock, R. A framework for assessing the quality of green infrastructure in the built environment in the UK. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artmann, M.; Bastian, O.; Grunewald, K. Using the concepts of green infrastructure and ecosystem services to specify Leitbilder for compact and green cities—The example of the landscape plan of Dresden (Germany). Sustainability 2017, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzimentor, A.; Apostolopoulou, E.; Mazaris, A.D. A review of green infrastructure research in Europe: Challenges and opportunities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Economic Area. Green Infrastructure and Territorial Cohesion. The Concept of Green Infrastructure and Its Integration into Policies Using Monitoring Systems; European Environment Agency: Luxembourg, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, H. Understanding green infrastructure: The development of a contested concept in England. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional ecology, translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907–39. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, S.L. This is not a boundary object: Reflections on the origin of a concept. Sci. Technol. Human Values 2010, 35, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, F.; Massetti, L.; Sanesi, G.; Pearlmutter, D. Knowledge transfer between stakeholders in the field of urban forestry and green infrastructure: Results of a European survey. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdam, P.; Westerink, J.; Vos, C.; De Vries, B. The role and evolution of boundary concepts in transdisciplinary landscape planning. Plan. Theory Pract. 2015, 16, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilker, J.; Rusche, K.; Rymsa-Fitschen, C. Improving participation in green infrastructure planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2016, 31, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S.; Thompson-Fawcett, M. Public participation and new urbanism: A conflicting agenda? Plan. Theory Pract. 2007, 8, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyet, V.; Schlaepfer, R.; Parlange, M.B.; Buttler, A. A framework to implement stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 111, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.B. Scoring the participatory city: Lawrence (& Anna) HALPRIN’S take part process. J. Archit. Educ. 2011, 64, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N. Designerly ways of knowing. Des. Stud. 1982, 3, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vree, D.; Dehaene, M.; Dumont, M. Ontwerpmatig Onderzoek en Ruimtelijke Transformaties; Departement Ruimte Vlaanderen: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Geldof, C.; Janssens, N. Van Ontwerpmatig Denken Naar Onderzoek; Vai: Antwerp, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, L.; Goethals, M. Planning tactics of undefined becoming: Applications within urban living labs of Flanders’ N16 corridor. In Materiality and Planning: Exploring the Influence of Actor-Network Theory; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 186–202. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, L.; Goethals, M. Living labs: Co-evolutie planning met onderzoekers, overheden, burgers en ondernemers voor uitvoerbare ruimtelijke projecten. Steunpunt Publicaties 2015, 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. The Design Charrette: Ways to Envision Sustainable Futures; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, Germany, 2013; ISBN 9400770316. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, J. Circular Economy Transition in Flanders; Katholieke Universiteit Leuven: Leuven, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari, J.R.; Arico, S.; Báldi, A.; et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework—Connecting nature and people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkelboom, F.; Raquez, P.; Dufrêne, M.; Raes, L.; Simoens, I.; Jacobs, S.; Stevens, M.; De Vreese, R.; Panis, J.A.; Hermy, M.; et al. CICES going local: Ecosystem services classification adapted for a highly populated country. In Ecosystem Services; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 223–247. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S.; McTaggart, R.; Nixon, R. The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research; Springer Science & Business Media: Singapore, 2013; ISBN 9814560677. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, G.; Cardiff, S.; Van Lieshout, F. Actieonderzoek: De praktijk centraal. TVZ 2018, 128, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, E.; Apostolopoulou, E.; Adams, W.M.; Bormpoudakis, D. Biodiversity and Green Infrastructure in Europe: Boundary object or ecological trap? Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, V.; Goethals, M.; De Meulder, B.; Schreurs, J.; Moulaert, F. Beyond design and participation: The ‘thought for food’ project in Flanders, Belgium. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 412–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smets, J.; De Blust, G.; Verheyden, W.; Wanner, S.; Van Acker, M.; Turkelboom, F. Starting a Participative Approach to Develop Local Green Infrastructure; from Boundary Concept to Collective Action. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310107

Smets J, De Blust G, Verheyden W, Wanner S, Van Acker M, Turkelboom F. Starting a Participative Approach to Develop Local Green Infrastructure; from Boundary Concept to Collective Action. Sustainability. 2020; 12(23):10107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310107

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmets, Jasmien, Geert De Blust, Wim Verheyden, Saskia Wanner, Maarten Van Acker, and Francis Turkelboom. 2020. "Starting a Participative Approach to Develop Local Green Infrastructure; from Boundary Concept to Collective Action" Sustainability 12, no. 23: 10107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310107

APA StyleSmets, J., De Blust, G., Verheyden, W., Wanner, S., Van Acker, M., & Turkelboom, F. (2020). Starting a Participative Approach to Develop Local Green Infrastructure; from Boundary Concept to Collective Action. Sustainability, 12(23), 10107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310107