Abstract

Reputation is considered an intangible asset that provides a competitive advantage in organizations, although in the field of education, its study and, specifically, its antecedents need further study. The aim of this paper is to analyze the effect of sustainability, innovation, perceived performance, service quality, work environment and good governance on reputation in private graduate online schools. This study is based on quantitative data collected from a survey. The sample consists of 349 students from a private graduate online school. The results obtained through PLS-SEM show that sustainability, service quality and good governance have a positive and significant influence on reputation. However, innovation, perceived performance and governance do not have a positive effect on the reputation of this type of organization. Therefore, more studies covering a greater sampling variety are required to determine the generalizability of these results. This study is a useful contribution since it will help managers of the private graduate online schools to know which aspects generate more reputation and, therefore, are the most valued by the public, so that the organization has a basis for decision-making.

1. Introduction

Reputation is an intangible asset that has been recognized as an essential part of corporate management, which provides great strategic value for creating long-term competitive advantages [1,2]. Reputation by itself synthesizes information about the company, its product, its relationship with customers, competitors and suppliers, as well as providing information on the reliability and credibility of the corporation, determining the public’s favorable response towards it [3]. Reputation is built over time, is nonnegotiable, and is one of the most important determinants of the prevalence of any organization. While strategies can always be altered, a severely damaged reputation is very difficult to recover [4].

In the specific case of educational institutions, reputation is often more important than its actual quality, as it embodies the perceived excellence of the institution, which will positively influence future Student’s towards a particular institution [5].

Research by Vidaver-Cohen [6] and Lukman and Glavič [7] reveal that reputation is derived largely from perceptions related to innovation, governance, organizational performance, work environment, quality of services and the application of sustainability principles in the activities of educational institutions. As a result of this, the purpose of this research is to increase current empirical evidence on the level of influence of each of the six variables mentioned on the reputation of private graduate online schools. This will make it possible to validate a model that generates relevant academic and management implications.

The decision to investigate variables that could affect the reputation of private graduate online schools derives, first, from the interest shown by a private school and the facilities granted to researchers to apply the questionnaires and collect the information. Second, the fact that a typical educational institution usually has material resources and facilities such as laboratories and library, that help to create a positive image in potential students; whereas, in the case of private graduate online schools, most of the infrastructure is virtual, so it does not make the same impression on students. As a result, other elements must be used to build or enhance their reputation. For this reason, it is worthwhile to focus our research on private graduate online schools. Third, there is a lack of specific research on the relationship between the variables chosen and this type of educational institution. For this reason, we believe that part of the relevance of this study is that it provides information related to private graduate online schools and contributes to the debate on reputation in universities that do not have the physical facilities to positively impress and attract their future students.

We acknowledge that our research is only focused on a private educational institution. We also are aware of the limitation this implies, but with the spirit of extending it in the future to other institutions in order to enrich our conclusions.

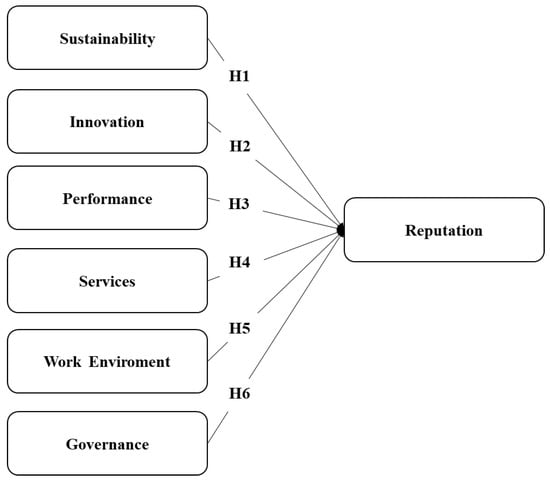

The model to be examined in this research aims to establish a reference framework of how sustainability, innovation, perceived performance, quality of services, work environment and governance affect the reputation of private schools of higher education. This can contribute to the fact that managers can take actions to obtain a competitive advantage in these types of institutions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed model.

The structure of this work will be as follows: First, we make a general review of theories and research on reputation, emphasizing the findings in the educational area, which the research hypotheses proposed are based on. Second, we explain the methodology that we apply and measure the influence of each variable on reputation. Third, the results obtained are discussed. Finally, we present the conclusions, the limitations of this study and the implications for future research.

2. Literature Background

2.1. Reputation and Educational Organizations

Reputation can be understood as the set of characteristics linked to personality and the perception or image of the organization. An organization not only wants to have a positive reputation, but it also expects the public to recognize certain distinctive characteristics in it, which will help its position with respect to others. The construction of the desired perception arises from the variables that can easily be manipulated by the organization, which will allow outlining an identity of its own and clearly differentiated from other organizations [8]. Corporate reputation can be studied from the perspective of the consumer or end-user [9]; from the perception of the external or internal public [10]; from a sociological perspective, meeting the expectations and norms in an institutional context [11]; as an intangible asset that can produce economic value [12] or as a strategy that can be managed from within the organization [13].

Reputation as a corporate strategy is built through the continuity and consistency of the perception of an organization and its proximity to society, as well as its needs. A positive reputation is linked to the public’s trust in the organization, and it is a long-term construct. Appropriate management of corporate reputation generates value and is one of the most relevant financial indicators for the assessment of public and private organizations [14]. In the case of educational institutions, reputation is frequently more critical than their real quality, as it embodies the perceived excellence of the institution, which will positively influence future students towards a particular institution. Therefore, we can say that the reputation of an educational organization is one of its main intangible assets and is crucial to generate interest and demand for educational services.

In higher education institutions, reputation is defined as the set of perceptions and evaluations that stakeholders differently performed for over specific time, and has its origins in past behavior, their communications and their ability to meet the needs of your stakeholders better than your competitors [15]. Alessandri [16] establishes the reputation as the collective representations that the university’s multiple stakeholders have of the university over time.

In the current competitive environment where universities are all competing globally for the best students, projects and cooperation, reputation is a key resource that serves to reduce the intangibility of the higher education service and increase its level of perceived quality [1,17]. Thus, obtaining a positive reputation will determine the survival of the university in the face of competition in the sector [12,18].

Despite being unanimous on the importance of reputation, it is broken in terms of the elements of its management [1,19]. Alessandri et al. [16] identified reputation with the quality of academic performance, the quality of external performance and emotional engagement. Brewer and Zhao suggested leadership, teaching, research, service offered and quality as dimensions of reputation. Martensen and Gronholdt [20] stated that innovation, services and the performance perceived by the public are decisive for building a solid reputation.

According to Verčič et al. [19], one of the main reputational frameworks in the field of higher education is that established by Vivader-Cohen. Vidaver-Cohen [6] states that creating a reputation is largely derived from the perceptions related to innovation, governance, organizational performance, the work environment and the quality of services. While Lukman and Glavič [7] stress that educational institutions have the duty to adopt and promote sustainability principles because they play a fundamental role in the education of future generations and thereby improve their image.

In light of these studies, it is possible to conclude that sustainability, innovation, perceived performance, service quality, work environment and governance provide intangible value and affect the public’s perception. However, for appropriate strategic management, it is necessary to know the effect that each of these variables has on creating a reputation [19].

In other words, it is necessary to know which aspects generate more confidence and, therefore, are the most valued by the public so that the organization has a basis for decision-making. Considering the above, the aim of this study is to measure the effect of each of these variables on the reputation of the university sector in online graduate teaching based on the hypotheses proposed for this research.

2.2. Reputation and Sustainability

In the literature, there are various approaches to the study of sustainability. In its origin, sustainability was linked to concern for the conservation of natural resources. In 1987 the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) of the United Nations (UN) established that sustainability refers to meeting the needs of the present without affecting the capability of future generations to meet their needs [19,21,22,23,24]. Later, the UN adopted a multidimensional vision that considers economic development, social development and environmental protection as three interdependent dimensions that lead to sustainable development. Economic sustainability involves a business contribution to achieving the viability of the economic system as a whole; social sustainability is aimed at the population’s aspirations regarding issues on equity, inclusion and health; finally, caring for the environment is linked to the application of forms of production with minimum impact on ecosystems [20].

Reputation is one of the most important factors of the prevalence of any organization [1,25]. We know that there is a positive relationship between the organization’s sustainable practices and its reputation [6,26]. Previous research shows that a company’s reputation is a determining factor in sustainability disclosure [27,28]. The companies that develop actions claim to obtain a greater commitment and positive perception from their stakeholders. From a financial point of view, sustainability compromises the level of reputation, companies that have linked to sustainability increase the value of their cash flows [29,30]. The BSR/GlobeScan 11th Annual State of Sustainable Business Survey 2019 reveals that reputation is one of the most important causes of sustainability efforts in companies. Sustainable practices in schools reveal to be the most proper approach to accomplish quality education and, consequently, reputation [29].

In the context of higher education, an increasing number of universities are incorporating sustainable development programs [31,32]. Universities are not only responsible for carrying out their teaching and research work, but they also have the duty to identify the needs of internal and external actors, adapt research to solve important problems, share useful knowledge and be responsible for their decisions from the social, environmental and economic point of view [33,34].

In general terms, sustainability is the philosophy of a university that applies an ethical approach to develop and link with the local and global community in order to generate its social, ecological, environmental, technical and economic development [35]. Sustainability implies “education, research, community outreach, operations, assessment and reporting, university collaboration, institutional framework, educate-the-educator programs, and campus experiences”. Sustainability in educational institutions also involves the effort to commit to local and regional initiatives to increase public awareness [36]. The sustainability programs are linked to aspects such as teaching, research, university collaboration, greenhouse gas reduction on campus, the participation of the university community in local programs [36,37].

Previous studies have suggested the relationship between sustainability and reputation in the context of higher education. Manzoor et al. [38] establish that external communication, values, international recognition, economic value or university facilities improve perceptions (reputation) among students, which in turn, encourages greater behavior of collaboration, help and support to the sustainability of higher education institutions. Shiel and Williams [32] affirm that the development of sustainable actions by an educational institution means promoting synergies between university roles, improving people’s quality of life and providing solutions to global problems [39] and affect the reputation of the institution [36]. Salvioni et al. [40] affirm that sustainability is a key success factor in improving the quality, image and positioning of universities in international rankings, aspects related to reputation.

Thus, the sustainable behavior shown by schools helps to improve the public’s perceptions and expectations. The first research hypothesis reflects this idea.

Hypothesis 1.

Perceived sustainability influences reputation positively.

2.3. Reputation and Innovation

Education and innovation make up an essential link in the knowledge economy. From an educational perspective, innovation means introducing improvements and updates based on the set of elements related to the teaching–learning process, subject to assessing its effectiveness and relevance. Educational innovation is therefore related to improving the design and development of the curriculum, improving teaching strategies and the curriculum components, such as educational materials and approaches and training, selection and professional development of teachers [41]. Adaptation to change is essential in the case of innovation in the education sector. Different authors [42] state that change is the origin and result of innovation. Consequently, educational institutions must be flexible in the face of change if they really want to generate innovation and generate projects that lead to experimentation, renewal and educational improvement.

Due to high competition within the education sector, innovation is the differentiating element for universities that seek to excel both in educational services and offer, as well as in research [43]. The reputation of an educational institution can, therefore, be expected to improve as its innovation projects do. In this regard, the perception of the quality of research activity was a strategic factor for the university to attract potential clients [44]. On the other hand, the findings of other studies confirm that the attraction factor which is perceived as the most important by students is the academic and research quality of the institution [45].

In the field of business schools, innovation activities involve addressing current economic problems, the development of research centers to increase the experience of teaching staff, collaboration with companies and the development of online distance learning [25]. Business schools that have a strong capacity to address these aspects over time will exceed the expectations of their stakeholders and have a positive impact on their reputation. In other words, innovation activities will predict positive evaluations of the reputation if they contribute to an improvement in educational quality over time [46]. Thus, innovation activities related to innovation, such as having a contemporary study program, follow trends related to the transmission of knowledge and adapting quickly to the times, will have a positive impact on the reputation of a business school [19]. Educational institutions try to offer courses and training related to innovations in engineering, economics, biology, business and society. The use of renewable energies, recycled materials, smart designs, office waste reduction, digital books and teaching materials also indicates that innovation and research programs are also applied for their own purposes, which causes a positive impact on stakeholders. [47,48].

The second research hypothesis was established based on this information.

Hypothesis 2.

The perceived innovation of the institution influences its reputation positively.

2.4. Reputation and Perceived Performance

Perceived performance is a subjective evaluation of how well a product or service functions that may lead a customer to show satisfaction and recommend the product or, on the contrary, to express disappointment and give the product a negative review. Educational institutions are continuously assessed by the public based on perceived performance. These results are, in turn, linked to the prestige, employability of its graduates and relationships with other entities, which favor both the institution itself and its students and graduates [12]. There are several studies that explore the relationship between perceived performance and organizational reputation. Reputation is studied from two dimensions: the public’s perception regarding its capability to produce quality goods, which is linked to a reduction in stakeholders uncertainty when choosing products and services from a supplier; and perception regarding the relevance of the organization measured through the status of third parties that support the organization, in other words, recognition in its field [49]. Researcher’s findings reveal that, while the former is strongly influenced by student performance, the latter depends on the support and backup of influential third parties, such as institutional intermediaries and high-status actors. In addition, the prestige of academic degrees showed a significant direct effect on the relevance of the organization and its reputation. In this regard, it is observed that graduates from the top universities, according to UK rankings that value top-level research activity, high-quality teaching processes and links with the public and private sector, obtained more job interviews and higher annual salaries than those who had graduated from universities with lower rankings [50]. Different investigations support that aspects of performance such as, employing prestigious professors or those who have high levels in publications, attract the best students, get good jobs after graduation, and have projects with high levels of income, are predictors of the reputational performance of a business school [19,25]. Higher levels of performance increase the visibility of business schools and enhance their organizational reputation [51,52]. Therefore, we consider that there is a strong effect between perceived performance and reputation.

These arguments support the third hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3.

The perceived performance of the institution influences its reputation positively.

2.5. Reputation and Quality of Service

Consumers do not purchase goods or services but purchase options that provide services and create value [53]. As consumers perceive that the service purchased generates more benefits, the greater the probability that the consumer will repeat the experience. In turn, increased demand for a product or service tends to increase its reputation among consumers. Previously, we pointed out that great challenges are faced by the education sector, which have led universities to make strategic decisions to deal with them. One of these challenges is to maintain student loyalty based on the quality of the service, which can be measured based on processes and performance. At the same time, the quality of the service affects the public’s perception of a university [8].

Reputation and consumer satisfaction in terms of the quality of the service received are closely related. For example, Nguyen and LeBlanc, [54] argue that image and reputation are a key element of loyalty, which at the same time, is linked to satisfaction shown by the quality of the service received [55,56]. Different studies argue that student loyalty is based on their perception of the quality of teaching and administrative services [57,58], whereas Ali et al. [59] argue that service quality is positively related to satisfaction. In conclusion, services create satisfaction for consumers (students): the greater satisfaction, the greater user loyalty. Loyal and satisfied users, in turn, have a positive effect on the organization’s reputation. The fourth hypothesis reflects this idea.

Quality of service in educational institutions brings up for discussion the problem of quantity instead of quality in higher education what results in deficiencies in training, inferior graduate performance and scarcity of job offers [60]. Stakeholders are aware that quality of service is not only related to courses delivery and quality of teaching but also associated with other core items such as adaptability to the market trends, good value for money and development of employability skills reflects the quality of service [61].

In the context of business schools, positive perceptions of the quality of services are a fundamental element in the evaluation of reputation [49]. The positive perceptions of the quality of a business school are related to the employability rate of its students, specialized skills training, high-quality instruction, good value for the money [25]. Other research indicates positive quality perceptions of a business school are associated with helping students find employment after graduation, high-quality lectures, and gives a lot for tuition [19]. Khoi et al. [62] found a positive impact between the quality of the service and the university reputation. Dehghan et al. [63] established a positive relationship between service quality and reputation in online educational systems.

Hypothesis 4.

The quality of the service provided influences its reputation positively.

2.6. Reputation and Work Environment

As mentioned previously, reputation is not merely an economic issue, but it is also a sociological one, linked to the sources of social support formed by the groups involved that would be responsible for supporting or rejecting the organization [64]. Thus, when the public recognizes an organization as a good place to work, it refers indirectly to the organization’s work environment. The work environment results from the interaction of physical factors, the structure, the staff, the functions and the culture of an organization resulting from a specific dynamic process of the organization that generates a distinctive personality, which influences its products [65]. As in any other sector, in the education sector, the work environment is directly related to the achievement of results, in this case not only of an academic nature but also of personal, professional and organizational development. The work environment is analyzed from two aspects: students’ perception of the environment in the educational center and as an organizational quality [66]. The work environment affects the behavior, attitudes and commitment of workers with the organization, and in turn, job performance affects the reputation of the organization [67]. There are several studies that show links between the work environment and academic performance, the growth prospects of the organization, job satisfaction and participation in academic activities and innovation, which conclude that the work environment is a factor that can determine academic, personal and social achievements [68,69,70].

In this line, previous research has suggested that different attributes of the work environment, such as rewarding employees and teachers fairly, showing interest in their teachers’ concerns, and offering equal opportunities, are antecedents that relate the work environment to organizational reputation [19,25]. In a study of business schools, attributes such as work climate, recognition of achievement, professional development, and the school’s ability to provide a satisfactory balance between work and family were the most prominent reputational elements of teacher attraction and retention [71]. Research related to the work environment and job satisfaction of teachers analyze as main factors of their evaluations the stress and anxiety of publishing, teaching and university service, obtaining an adequate salary, and meeting the demands of academic associations and the local community [35,72,73]. Thus, the lack of attention to the concerns and needs of teachers can have serious negative consequences for a higher education school, diminishing its effectiveness, its competitive position and its reputation over time [8,74]. In other words, institutions that offer employees or faculty a fair reward for their work, show concern for their well-being, and offer equal opportunity (attributes related to the work environment) can contribute to increasing their reputational level.

The fifth hypothesis is established based on these arguments.

Hypothesis 5.

Perceived work environment positively influences the reputation of the institution.

2.7. Reputation and Governance

When measuring intangible assets related to activities that provide value to companies, the norms, principles and procedures that define the structure and operation of the organization’s governing bodies, that is, governance or corporate governance, stand out [75]. We can define good governance as the public administration process that englobes legitimate, accountable and effective ways to maximize resources in the pursuit of social goals [66]. According to Shattock [76], university governance is defined as the constitutional forms and processes whereby universities govern their affairs.

There are studies [77,78] that state that good governance has a positive effect on image and reputation. At the same time, the mistakes made in the governance of some companies have ruined their reputation and, at times, that of the sector as a whole, which has given rise to various studies in this regard. Different researchers studied poison pills or dissuasive practices to avoid a hostile acquisition, as well as the penalty that corporations receive when they apply them and found that when the media learns of these controversial governance practices, corporate reputation is affected negatively [79,80]. In the specific case of educational institutions, Downes [81] studied the repercussions caused by bad governance and found that enrolment decreases and donors withdraw when governance fails in its commitment to monitor and apply corrective actions to prevent deteriorating the organizational reputation.

The needs of the market and the consequences of failures in corporate governance have led European educational institutions to reform and modernize their structures and processes to respond to growing social needs associated with innovation, sustainability, entrepreneurship and job creation in order to increase the competitiveness of European countries. The governance model chosen by a particular educational institution determines its capability to have an impact on society and contribute to the country’s economy and the knowledge society. In other words, the organization must clearly reflect how its form of governance makes it possible to respond to such demands [82]. The governance of an organization gives it a unique character and is essential to generate incentives that attract the necessary investments for the development of the company and generate a favorable image for customers, suppliers, employees, communities and funders.

Developing better governance models requires a continued dedication to recognizing what the educational institution wants to become in terms of clarity and transparency, decision-making and stakeholders’ views [83]. Bratianu and Florina [84] define university governance as the constitutional forms and processes through which universities govern their affairs. Downes [81], in a review of the literature, suggested that adequate management of corporate governance serves to improve the reputation in a situation of university scandals. Other research suggests that transparency, ethics and fairness are the governance-related elements that enhance the reputation of a business school [19,25]. Thus, to the extent that interested parties are affected or informed about the governance procedures of a business school, such as transparency, the demonstration of ethical behavior or fairness in relationships with its stakeholders will enhance its reputation.

This idea is reflected in the sixth hypothesis.

Hypothesis 6.

The good governance of the institution positively influences the reputation of the institution.

3. Research Methodology

The hypotheses presented were tested on the online postgraduate university sector since, as previously mentioned, these organizations must compete nationally and internationally with other institutions to guarantee their survival. Specifically, the chosen field of research was Spanish private online graduate schools, since, as is in the case of other countries, they must identify and improve their sustainability, innovation, perceived performance, quality of service, work good environment, governance and reputation to improve and maintain their situation in the sector. In fact, the number of students has increased in private graduate schools; they are investing in marketing elements due to the fact that public budgets are decreasing. Information from students at a private online graduate school was obtained (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Empirical research data.

To collect data, in a first step, an online pretest was distributed to 50 students in order to verify if the items on the scale and adapt them if necessary. In a second step of the pretest, the results were analyzed, and some items were modified to clarify their meaning and adjust the response time; others were removed. Finally, 349 valid responses were collected, 41% being men and 59% women.

Different studies have highlighted that reputation is formed by a set of different attributes perceived by stakeholders; therefore, it can be measured as a multidimensional concept [12,13,19]. Authors such as Chun consider reputation as a multidimensional element, where, unlike the image, it is formed by the evaluations of perceptions of both external and internal authorities. Other authors [85] affirm that reputation is multidimensional and can be measured by three dimensions: the corporate reputation, the reputation of the product or service and the reputation of the organizational structure. Authors as [86] suggest that the dimensions of reputation are: corporate, product or service quality and financial. For other authors, the dimensions of reputation are related to product communication, social actions, financial and work performance [1,87,88]. Other investigations consider the quality of the service, innovation, quality of management and the work environment the dimensions of the reputation [89].

In higher education, aspects such as the size of the faculty, the academic level of its professors or the amount of graduation fees are relevant for the measurement of reputation [90,91]. Other research considers leadership, teaching, level of research and quality of service as reputation dimensions [16]. Vidaver-Cohen [25] developed a reputation measurement model. In this model, reputation included dimensions such as performance, innovation, services, governance, citizenship and the work environment. Finally, other studies have included sustainability as a relevant element in the reputation of higher education schools.

All the constructs were measured through reflective items (type A) and were adapted to higher education existing scales used by other studies. The items to measure the constructs were sustainability [6,92,93]. Work environment, perceived performance, quality of service, innovation, governance and reputation [19,25,74]. To measure the variables, an 11-point ascending Likert-type scale was used, with 0 totally disagreeing and 10 totally agreeing (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Items used and descriptive analysis.

For data processing and hypothesis testing, the PLS-SEM method and SmartPLS3 V.3.3.3 software are used. PLS-SEM compared to other methods such as CB-SEM or AMOS (based on covariances), is a multivariate analysis method that is mainly designed for exploratory studies and whose main purpose is to predict dependent variables by estimating path models [8,92,93]. These reasons justify your choice.

4. Results

4.1. Results of Descriptive Analyses

The descriptive statistics results for each of the questions in the questionnaire are shown in Table 1. The results show average values greater than 6.5 for all of them. Regarding sustainability and its indicators, the SUST2 indicator has low mean values (for example, a value of 6.694 in the question of whether your university supports charitable causes). Regarding the work environment and its indicators, the WORK1 indicator obtains the highest mean values (for example, a value of 8.112, in the question of whether employees are competent). Regarding perceived performance and its indicators, the PERF3 indicator has the lowest value (for example, a value of 6.913, in the question of whether the institution has growth prospects). The variables of service quality, innovation and reputation obtain adequate values when they are between approximately 7 and 8. Regarding good governance and the other variables, the GOVE2 indicator has the lowest mean value (for example, a value of 6.596, in the question of whether it takes its stakeholders into account in decision-making).

4.2. Results Using PLS-SEM

In order to evaluate the proposed model by using PLS-SEM, we will first analyze the assessment of the measurement model and, subsequently, evaluate the structural model.

The assessment of the measurement model of type A indicators involves analyzing the individual reliability of its items by analyzing their loadings, the reliability of the construct through Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), Dijkstra–Henseler statistic (rho_A). The assessment of the measurement model also requires analyzing convergent validity through the average variance extracted (AVE) [94].

Table 3 shows that the values of the loadings of the individual indicators and CA are higher than the recommendation of 0.7 [94,95]. The CR values shown are above 0.6 or 0.7 and are considered adequate [17,96]. Furthermore, AVE values above 0.5 indicate that there are no convergent validity problems [97].

Table 3.

Measurement model of reliability and validity.

To analyze the discriminant validity of reflective constructs, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) has been analyzed [35,98]. Kline [99] suggests values lower than 0.85. As Table 4 shows, the data are valid when their values are adapted to what is indicated above.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

Once the assessment of the measurement instrument was carried out, we will proceed to evaluate the structural model. The analysis of the structural model requires studying the possible existence of multicollinearity through the VIF, the significance of the path coefficients and the determination coefficient R2 [94]. Table 4 shows that there are no multicollinearity problems when values below 3 are obtained [94]. Furthermore, they confirm that sustainability, service quality and good governance influence reputation positively and significantly by obtaining the path coefficient a p-value lower than 0.05. On the other hand, innovation, performance and the work environment do not have a significant influence on reputation by obtaining a p-value higher than 0.05 [94]. For the evaluation of the structural model, after analyzing the statistical significance, the coefficient of determination R2 must be evaluated [94]. This coefficient represents a measure of predictive power and indicates the amount of variance of a construct that is explained by the predictor variables of the endogenous construct in the model. Table 5 shows that the results of the R2 coefficient for reputation are between 0.50 and 0.75. These values in the field of marketing are considered moderate values [94]. In addition, the predictive relevance of the model is also shown since the Q2 value is greater than zero [94].

Table 5.

Contrast of the structural model.

Therefore, as Figure 2 shows, the influence of innovation, performance and work environment on reputation (relationships H2, H3, H5) is rejected, while the influence of sustainability, quality of service and good governance on reputation are accepted (H1, H4, H6).

Figure 2.

Results of the structural model.

5. Discussion of Results

In this research, we have analyzed the effects of perceptions of sustainability, innovation, performance, services, work environment, governance on the reputation of an online graduate school. The results of this work represent a useful contribution to the relationship of these variables on reputation in the field of an online graduate school. They enable us to empirically validate relationships proposed by the theory, confirm and reinforce the results shown in other studies or generalize results shown in business environments. The PLS-SEM results revealed a positive and significant effect of sustainability, service quality and governance on reputation (H1, H4 y H6). Therefore, the results highlight the importance of the perceptions of these three variables on reputation. Previous studies have confirmed a positive and significant effect of sustainability on reputation [78,100,101], which indicates that the results of the present study are consistent with previous studies. However, these studies analyzed it in other contexts. Ramos y Gonzalez [78] did it on large Spanish firms defined as sustainable by the corporate reputation business monitor (MERCO) and Igbud [100] about the banking sector. In the current study, we found that in an online graduate school, the effect size of sustainability perceptions has a positive and significant effect on its reputation. Therefore, online graduate schools that have high positive levels of sustainability will obtain higher levels of reputation than those that do not have high levels of sustainability. The results also show that service quality and governance have a positive and significant effect on reputation. Different studies have confirmed a positive and significant effect on service quality and governance [25,102]. This highlights the consistency of the results. However, these studies have analyzed it in face-to-face education settings. In our research, we observed that online graduate schools that have high levels of perception of quality of service and governance would have a higher level of reputation. In addition, in relation to the size of the effects, the quality of the service offers a greater influence on the reputation than the sustainability and the governance. This aspect highlights the importance of service quality in obtaining a high level of reputation in online environments. Previous studies have supported the importance of marketing and obtaining a high level of quality of service that allows obtaining a positive reputation and a greater relationship with its stakeholders [62,103]. Therefore, from the point of view of relationship marketing, those online higher education institutions that obtain a high level of quality service with their stakeholders generate a competitive advantage through a higher level of reputation [104,105].

On the other hand, the results show that innovation, perceived performance and the work environment do not have a positive and significant effect on reputation (H2, H3 and H5). However, different studies [19,25,102] have suggested a positive and significant effect on reputation in higher education schools. We found that in an online higher education context, students’ perceptions of innovation, performance and work environment did not significantly influence reputation. This may suggest that in a face-to-face higher education context, the influence of innovation, performance and the work environment is on reputation is greater than in an online education context. In this way, environments that offer greater experience, innovation, perceived performance and the work environment have a much greater effect than in online environments. In other words, perhaps previous experiences with students’ physical interaction play a major role in the perception of reputation [106]. Therefore, a longitudinal study is necessary to confirm when innovation, perceived performance and the work environment favor a positive influence on reputation.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Currently, in today’s volatile, changing and competitive economic environments, education institutions must improve their reputation since a positive reputation can provide a competitive advantage in terms of better economic results, greater commitment, attraction and retention of their stakeholders [107,108,109]. Different studies suggest different explanatory factors for reputation in higher education settings [19,25,102,110]. In this study, we have analyzed different explanatory factors that have a positive effect on reputation. Specifically, we have investigated the effect of sustainability, innovation, performance, services, work environment and governance on reputation in students at an online graduate school.

Analysis of the effects of sustainability, innovation, performance, services, work environment and governance on reputation makes a unique contribution. The contribution is made significant by the fact that we analyze these factors in a private online graduate school since there is a shortage of studies that appear in the literature in this type of organization [1,62]. Therefore, empirical evidence is still lacking to clarify the influence and relationships between these variables. However, in our work, we focus on the students of a private online graduate school; if we had focused on other types of actors such as teachers, managers or public educational institutions, our results could have been different. Therefore, this limited focus can be considered a limitation of our research and future research could make comparisons between different categories of stakeholders or institutions.

The results of this work have some practical implications for managers of public institutions of online higher education. Our results underscore the importance of sustainability over reputation. Therefore, in today’s increasingly volatile, uncertain and complex environment, sustainability plays a fundamental role so that organizations can obtain a competitive advantage that allows them to obtain a greater reputation [101]. For this reason, those responsible for this type of organization must develop sustainability actions such as, for example, increasing participation in volunteer programs, support for the local community, gender equality, transparency processes or reduction of environmental impacts, etc., and incorporate them into your reputation programs. In addition, it is also important that they communicate with them periodically and involve their stakeholders in their participation through suggestion boxes or alumni programs, where former students encourage the participation of new students.

Additionally, the results highlighted a strong and significant effect of service quality and governance on reputation. Therefore, managers of higher educations institutions must reinforce internal communication, training, training and motivation of their employees and obtain an orientation to the internal market that will have an impact on the positive perceptions of the quality of service and governance of your students and, in turn, in a more positive reputation. Future research may explore the limitation derived from unobserved sample heterogeneity. Although we previously justified the analysis of private graduate schools and of students, there could be greater heterogeneity within each group of stakeholders or type of intuitions.

The sample for this study consists of students from graduate schools. Therefore, more studies covering a greater sampling variety are required to determine the generalizability of these results. Furthermore, this study is limited to an investigation of the effects of perceived sustainability, innovation, performance, services, quality and work environment on the reputation of online graduate schools. In subsequent studies, researchers can further investigate these relationships in more segmented business organizations or explore the difference between public and private organizations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Project administration: J.M.-M., C.P.-R., and G.C.-R.; Funding acquisition: J.M.-M., and C.P.-R.; Writing–original draft: J.M.-M., C.P.-R., G.C.-R., and L.L.A.-M.; Performing the methodology and results: G.C.-R.; Conceiving and designing review: C.P.-R., G.C.-R.; Writing–review & editing: G.C.-R., and L.L.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Miotto, G.; Del-Castillo-Feito, C.; Blanco-González, A. Reputation and legitimacy: Key factors for Higher Education Institutions’ sustained competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taeuscher, K. Reputation and new venture performance in online markets: The moderating role of market crowding. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 105944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappeman, J.; Patel, M.; Appalraju, R. Firestorm Response: Managing Brand Reputation during an nWOM Firestorm by Responding to Online Complaints Individually or as a Cluster. Communicatio 2018, 44, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, S. Places: Identity, Image and Reputation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Munisamy, S.; Jaafar, N.I.M.; Nagaraj, S. Does reputation matter? Case study of undergraduate choice at a premier university. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 2014, 23, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønn, P.S.; Vidaver-Cohen, D. Corporate motives for social initiative: Legitimacy, sustainability, or the bottom line? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, R.K.; Glavič, P.; Carpenter, A.; Virtič, P. Sustainable consumption and production—Research, experience, and development—The Europe we want. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 138, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachón-Rodríguez, G.; Prado-Román, C.; Zúñiga-Vicente, J.Á. The relationship between identification and loyalty in a public university: Are there differences between (the perceptions) professors and graduates? Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abratt, R.; Kleyn, N. Corporate identity, corporate branding and corporate reputations: Reconciliation and integration. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 1048–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, M.; Raithel, S.; Schloderer, M. Recognition or rejection—How a company’s reputation influences stakeholder behaviour. In Reputation Capital; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bitektine, A. Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Castillo-Feito, C.; Blanco-González, A.; González-Vázquez, E. The relationship between image and reputation in the Spanish public university. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B.M. Fame & Fortune: How Successful Companies Build Winning Reputations; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vig, S.; Dumičić, K.; Klopotan, I. The impact of reputation on corporate financial performance: Median regression approach. Bus. Syst. Res. J. 2017, 8, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šontaite, M.; Bakanauskas, A.P. Measurement model of corporate reputation at higher education institutions: Customers’ perspective. Manag. Organ. Syst. Res. 2011, 59, 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri, S.W.; Yang, S.-U.; Kinsey, D.F. An integrative approach to university visual identity and reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2006, 9, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachón-Rodríguez, G.; Prado-Román, C.; Blanco-Gonzalez, A. Efectos de la imagen universitaria sobre la identificación y la lealtad: ¿existen diferencias significativas entre estudiantes y egresados? Rev. Espac. 2020, 41, 1015. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, C.T.; Hasan, N.A.M. Student’s perception on the selected facets of reputation quotient: A case of a malaysian public university. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2019, 2, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Verčič, A.T.; Verčič, D.; Žnidar, K. Exploring academic reputation—Is it a multidimensional construct? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2016, 21, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martensen, A.; Grønholdt, L.; Eskildsen, J.K.; Kristensen, K. Measuring student oriented quality in higher education: Application of the ECSI methodology. In Proceedings of the TQM for Higher Education Institutions II, Verona, Italy, 30–31 August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. Analyzing the intellectual structure of the Knowledge base on managing for sustainability, 1982–2019: A meta-analysis. Sustain. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hörisch, J. In search of the dominant rationale in sustainability management: Legitimacy-or profit-seeking? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelson-Powell, A.; Grosvold, J.; Millington, A. Business School Legitimacy and the Challenge of Sustainability: A Fuzzy Set Analysis of Institutional Decoupling. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2016, 15, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED World commission on environment and development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 17, pp. 1–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaver-Cohen, D. Reputation beyond the rankings: A conceptual framework for business school research. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 278–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leaniz, P.M.G.; del Bosque, I.R. Intellectual capital and relational capital: The role of sustainability in developing corporate reputation. Intang. Cap. 2013, 9, 262–280. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, K.; Guzman, F. How CSR reputation, sustainability signals, and country-of-origin sustainability reputation contribute to corporate brand performance: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 117, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, A.; Vidovic, M. Sustainability performance and assurance: Influence on reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2015, 18, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, I.C.; Callen, J.L.; Branco, M.C.; Curto, J.D. The value relevance of reputation for sustainability leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroufe, R.; Gopalakrishna-Remani, V. Management, social sustainability, reputation, and financial performance relationships: An empirical examination of US firms. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carracedo, F.; Ruiz-Morales, J.; Valderrama-Hernández, R.; Muñoz-Rodríguez, J.M.; Gomera, A. Analysis of the presence of sustainability in Higher Education Degrees of the Spanish university system. Stud. High. Educ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, C.; Williams, A. Working together, driven apart: Reflecting on a joint endeavour to address sustainable development within a university. In Integrative Approaches to Sustainable Development at University Level; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 425–447. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou, K.; Wiggins, J. Measuring individual legitimacy perceptions: Scale development and validation. Strateg. Organ. 2019, 17, 470–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepasi, S.; Braendle, U.; Rahdari, A.H. Comprehensive sustainability reporting in higher education institutions. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Gonzalez, A.; Diéz-Martín, F.; Cachón-Rodríguez, G.; Prado-Román, C. Contribution of social responsibility to the work involvement of employees. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Portela, N.; Benayas, J.; Lozano, R. Sustainability leaders’ perceptions on the drivers for and the barriers to the integration of sustainability in Latin American higher education institutions. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, N.; den Heijer, A.; de Jonge, H. Assessment tools’ indicators for sustainability in universities: An analytical overview. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 84–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, S.R.; Ho, J.S.Y.; Al Mahmud, A. Revisiting the ‘university image model’ for higher education institutions’ sustainability. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Valdez-Juárez, L.E.; Castuera-Díaz, Á.M. Corporate social responsibility as an antecedent of innovation, reputation, performance, and competitive success: A multiple mediation analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Franzoni, S.; Cassano, R. Sustainability in the higher education system: An opportunity to improve quality and image. Sustainability 2017, 9, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendenning, F.; Cusack, S.; Elmore, R.; Phillipson, C.; Withnall, A. The education for older adults ‘movement’: An overview. In Teaching and Learning in Later Life; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Havelock, R.G.; Huberman, A.M. Innovación y Problemas de la Educación: Teoría y Realidad en los Países en Desarrollo; Unesco: Paris, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Nava Lara, S.A.; Glasserman Morales, L.D.; Torres Arcadia, C.C. Innovación Educativa en Estudios Sobre Gestión Educativa: Una Revisión Sistemática de Literatura; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Akareem, H.S.; Hossain, S.S. Determinants of education quality: What makes students’ perception different? Open Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 3, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicker, R.; Garcia, M.; Kelly, A.; Mulrooney, H. What does ‘quality’ in higher education mean? Perceptions of staff, students and employers. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1425–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelo, H.; DeAngelo, L.; Zimmerman, J.L. What’s Really Wrong with US Business Schools? SSRN Electron. J. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, L.V.; Beuron, T.A.; Brandli, L.L.; Damke, L.I.; Pereira, R.S.; Klein, L.L. Barriers to innovation and sustainability in universities: An international comparison. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, L.V.; Leal Filho, W.; Brandli, L.; Macgregor, C.J.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Özuyar, P.G.; Moreira, R.M. Barriers to innovation and sustainability at universities around the world. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 1268–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.O.; Petkova, A.P.; Sever, J.M. Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drydakis, N. The effect of university attended on graduates’ labour market prospects: A field study of Great Britain. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2016, 52, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Márquez, B.L.; Escudero-Torres, M.A.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E. Being highly internationalised strengthens your reputation: An empirical investigation of top higher education institutions. High. Educ. 2013, 66, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltaru, R.-D. Do non-academic professionals enhance universities’ performance? Reputation vs. organisation. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 44, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E. Using internal marketing to develop a new culture—The case of Ericsson quality. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 1987, 2, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; LeBlanc, G. Image and reputation of higher education institutions in students’ retention decisions. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2001, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Langer, M.F.; Hansen, U. Modeling and managing student loyalty: An approach based on the concept of relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazoleas, D.; Kim, Y.; Anne Moffitt, M. Institutional image: A case study. Corp. Commun. An Int. J. 2001, 6, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Srivastava, S.C.; Jiang, L. Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamdevula, S.; Bellamkonda, R.S. The effects of service quality on student loyalty: The mediating role of student satisfaction. J. Model. Manag. 2016, 11, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Zhou, Y.; Hussain, K.; Nair, P.K.; Ragavan, N.A. Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty? A study of international students in Malaysian public universities. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2016, 24, 70–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, M. Measuring quality and performance in higher education. Qual. High. Educ. 2001, 7, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J. HEISQUAL: A modern approach to measure service quality in higher education institutions. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2020, 67, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoi, B.H.; Dai, D.N.; Lam, N.H.; Van Chuong, N. The Relationship among Education Service Quality, University Reputation and Behavioral Intention in Vietnam. In Proceedings of the International Econometric Conference of Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, 14–16 January 2019; pp. 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan, A.; Dugger, J.; Dobrzykowski, D.; Balazs, A. The antecedents of student loyalty in online programs. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2014, 28, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, C.; Aboagye, E.; Hagberg, J.; Bergström, G.; Lohela-Karlsson, M. Estimating the effect and economic impact of absenteeism, presenteeism, and work environment--related problems on reductions in productivity from a managerial perspective. Value Heal. 2017, 20, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, F.R.; Palerangi, A.M.; Tahir, I.A. Perception of Vocational High School Students in Makassar towards Working Environment and Preparedness in Facing Industrial World. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education, Science and Technology, Padang, Indonesia, 13–15 March 2019; pp. 438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Erkul, H.; Kanten, P.; Gümücstekin, G. The Effects of Structural Empowerment on Corporate Reputation and Organizational Identification. Acta Acad. Karviniensia 2018, 3, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulghani, H.M.; Al-Drees, A.A.; Khalil, M.S.; Ahmad, F.; Ponnamperuma, G.G.; Amin, Z. What factors determine academic achievement in high achieving undergraduate medical students? A qualitative study. Med. Teach. 2014, 36, S43–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutarto, J. Determinant factors of the effectiveness learning process and learning output of equivalent education. In Proceedings of the 3rd NFE Conference on Lifelong Learning (NFE 2016), Bandung, Indonesia, 22 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ulya, R.; Amir, A.; Yaunin, Y. Association between psychological profile and academic achievement of midwifery students. J. Midwifery 2018, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornuel, E.; Verhaegen, P. Academic talent: Quo vadis? Recruitment and retention of faculty in European business schools. J. Manag. Dev. 2005, 24, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, C.J.; Dee, J.R. Greener pastures: Faculty turnover intent in urban public universities. J. High. Educ. 2006, 77, 776–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.B.; Kane, W.D. Caught in the middle: Faculty and institutional status and quality in state comprehensive universities. High. Educ. 1991, 22, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Castillo-Feito, C.; Blanco-González, A.; Delgado-Alemany, R. The relationship between image, legitimacy, and reputation as a sustainable strategy: Students’ versus professors’ perceptions in the higher education sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Judge, W.Q.; Terjesen, S.A. Corporate governance deviance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattock, M. Managing Good Governance in Higher Education; McGraw-Hill Education: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nurdiniah, D.; Pradika, E. Effect of good corporate governance, KAP reputation, its size and leverage on integrity of financial statements. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-González Maand Rubio-Andrés, M.; Sastre-Castillo, M.Á. Building corporate reputation through sustainable entrepreneurship: The mediating effect of ethical behavior. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, M.K.; Love, E.G.; Kraatz, M. Paying the price? The impact of controversial governance practices on managerial reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1740–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Zingales, L. The corporate governance role of the media. SSRN Electron. J. 2002, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M. University scandal, reputation and governance. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 2017, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.V.; Aller, M.J.V. Gobierno, autonomía y toma de decisiones en la Universidad. Bordón. Rev. Pedagog. 2014, 66, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Trakman, L. Modelling university governance. High. Educ. Q. 2008, 62, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Pinzaru, F. University governance as a strategic driving force. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Management, Leadership & Governance, Lisbon, Portugal, 12–13 November 2015; pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt, K.; Camerer, C. Reputation and corporate strategy: A review of recent theory and applications. Strateg. Manag. J. 1988, 9, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger, M.J.; Golden, P.A.; Saxton, T. The effect of reputation on the decision to joint venture. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A.; Pratt, M.G.; Whetten, D.A. Identity, intended image, construed image, and reputation: An interdisciplinary framework and suggested terminology. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Van Riel, C.B.M. The reputational landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1997, 1, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R. Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkwein, J.F.; Sweitzer, K.V. Institutional prestige and reputation among research universities and liberal arts colleges. Res. High. Educ. 2006, 47, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gora, A.A.; Ștefan, S.C.; Popa, Ș.C.; Albu, C.F. Students’ Perspective on quality assurance in higher education in the context of sustainability: A PLS-SEM approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, K.; Predy, L.K.; Upreti, G.; Hume, A.E.; Turri, M.G.; Mathews, S. Perceptions of contextual features related to implementation and sustainability of school-wide positive behavior support. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2014, 16, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J. Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cachón-Rodríguez, G.; Prado-Román, C. The identification-loyalty relationship in a university context of crisis: The moderating role of students and graduates. Cuad. Gestión 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Igbudu, N.; Garanti, Z.; Popoola, T. Enhancing bank loyalty through sustainable banking practices: The mediating effect of corporate image. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineiro-Chousa, J.; Vizcaíno-González, M.; López-Cabarcos, M.Á.; Romero-Castro, N. Managing reputational risk through environmental management and reporting: An options theory approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomi, K. Exploring the dimensions of brand reputation in higher education--a case study of a Finnish master’s degree programme. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2014, 36, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadas, K.-K.; Avlonitis, G.J.; Carrigan, M.; Piha, L. The interplay of strategic and internal green marketing orientation on competitive advantage. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Moosa, K.; Imam, A.; Ahmed Khan, R. Service quality and student satisfaction: The moderating role of university culture, reputation and price in education sector of pakistan. Iran. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 10, 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, M.; Rodríguez-Voltes, C.I.; Rodríguez-Voltes, A.C. Gap analysis of the online reputation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Nazarian, A.; Ziyadin, S.; Kitchen, P.; Hafeez, K.; Priporas, C.; Pantano, E. Co-creating brand image and reputation through stakeholder’s social network. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, T.; Gornitzka, Å. Reputation management in complex environments—A comparative study of university organizations. High. Educ. Policy 2017, 30, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznik, S.D.; Yudina, T.A. Key Milestones in the Development of Reputation Management in Russian Universities. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2018, 7, 379–391. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).