Measurement of Service Quality in Trade Fair Organization

Abstract

1. Introduction

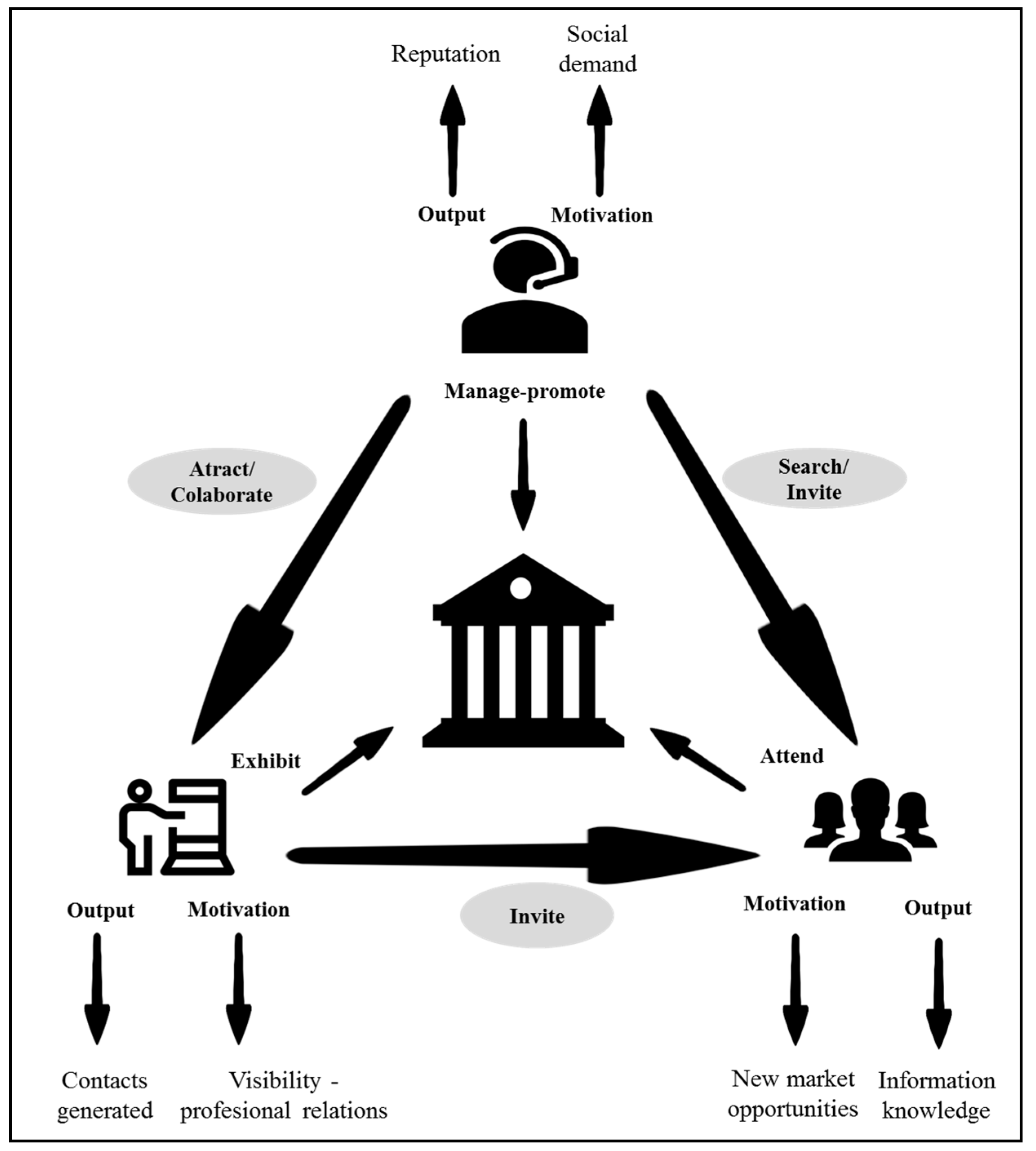

2. Theoretical Background

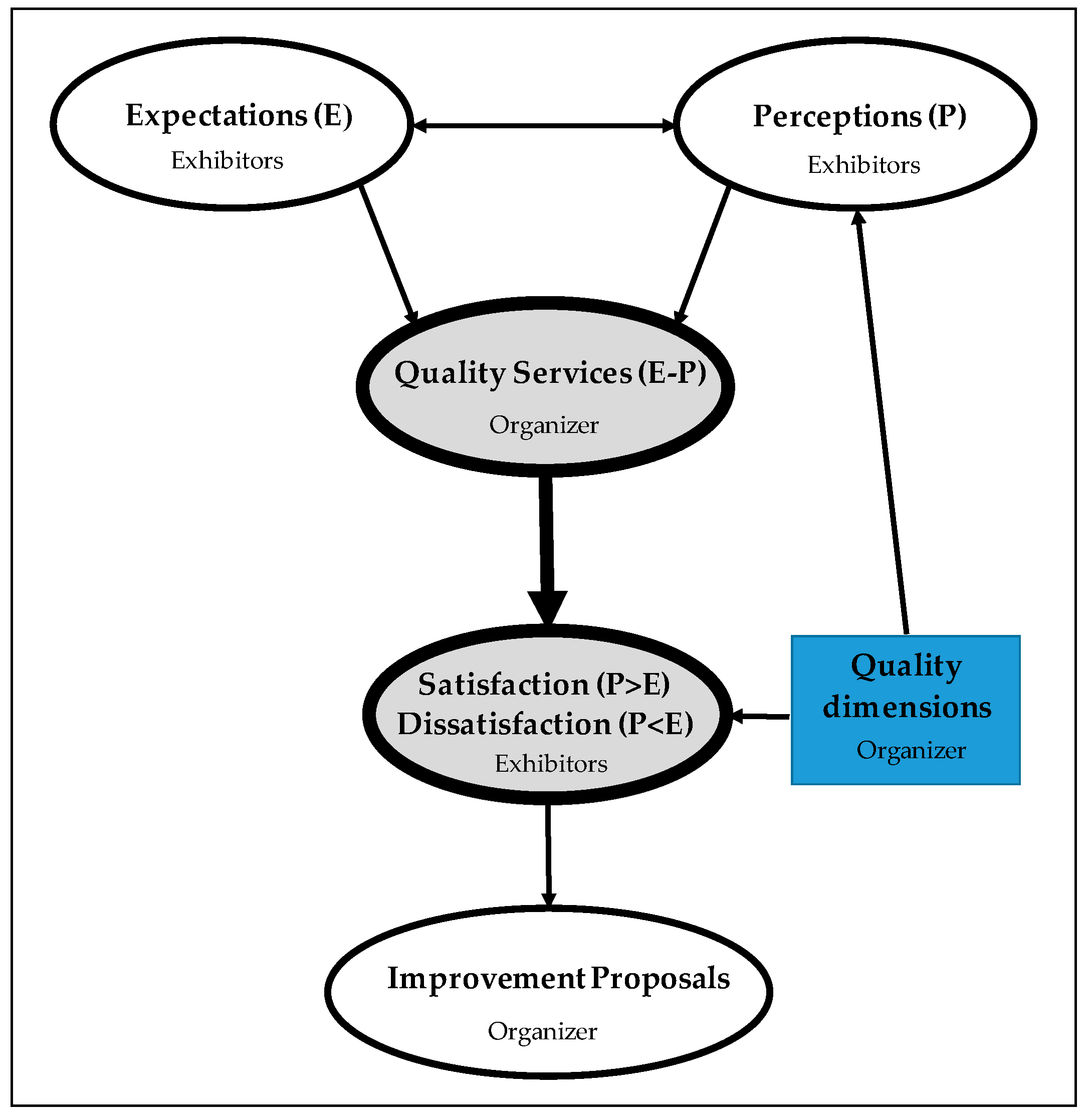

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Expectations and Perceptions of the Exhibitor

4.2. Analysis of Satisfaction of Exhibitor with the Organization of the Fair

4.3. Responsibility of the Organizer to Fulfill Exhibitor Expectations

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item |

|---|

| 1. Close sales agreements |

| 2. Establish new contacts with potential buyers |

| 3. Promote company image and improve reputation |

| 4. Conduct market research and gather information on competition |

| 5. Disseminate company information |

| 6. Recruit new distributors and sales representatives |

| 7. Make contact with professionals and specialists who would otherwise be difficult to reach |

| Item |

|---|

| 1. Fair facilities (size, design, functionality, conference halls) |

| 2. Parking |

| 3. Cafes, restaurants, etc. |

| 4. Information service and signage |

| 5. Cleanliness |

| 6. Technical services: Assembly, decoration |

| 7. Security |

| 8. Press office |

| 9. Promotion prior to fair |

| 10. Event date |

| 11. Quality and number of exhibitors |

| 12. Quality and number of visitors |

| 13. Professionalism |

| 14. Level of internationalization |

| 15. Attention received from fair stall |

References

- Rinallo, D.; Bathelt, H.; Golfetto, F. Economic geography and industrial marketing views on trade shows: Collective marketing and knowledge circulation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 61, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union of International Fairs (UFI). The Global Association of the Exhibition Industry. Available online: www.ufi.org (accessed on 25 October 2017).

- Puchalt, J.; Munuera, J.L. Panorama internacional de las ferias comerciales. Inf. Comer. Española 2008, 840, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kresse, H. The importance of associations and institutions in the trade fair industry. In Trade Show Management: Planning, Implementing and Controlling of Trade Shows, Conventions and Events; Kirchgeorg, M., Dornscheidt, W., Giese, W., Stocek, N., Eds.; Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; pp. 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rinallo, D.; Golfetto, F. Exploring the knowledge strategies of temporary cluster organizers: A longitudinal study of the EU fabric industry trade shows (1986–2006). Econ. Geogr. 2011, 87, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munuera, J.L.; Ruiz, S. Trade fairs as services: A look at visitors’ objectives in Spain. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berné, C.; García-Uceda, M.E. Modelización de la actuación de los expositores en feria y sus efectos. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2010, 19, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Situma, S.P. The effectiveness of trade shows and exhibitions as organizational marketing tool. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Geigenmüller, A.; Bettis-Outland, H. Brand equity in B2B services and consequences for the trade show industry. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2012, 27, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W. Understanding how resource deployment strategies influence trade show organizers’ performance effectiveness. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1009–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhitya, B.G. Exhibition service quality and its influence to exhibitor satisfaction. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2019, 111, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tafesse, W.; Skallerud, K. A systematic review of the trade show marketing literature: 1980–2014. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 63, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, M.; Simoes, C. The envolving role of trade fairs in business: A systematic literature review and a research agenda. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 73, 154–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeck, N.; Schraudy, K. From trade show company to integrated communication service provider. In Trade Show Management: Planning, Implementing and Controlling of Trade Shows, Conventions and Events; Kirchgeorg, M., Ed.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2005; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Weber, K.; Bauer, T. Relationship quality between exhibitors and organizers: A perspective from Mainland China’s exhibition industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1222–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E. Current and future trends in marketing and their implications for the discipline. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2004, 12, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchgeorg, M.; Jung, K.; Klante, O. The future of trade shows: Insights from a scenario analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2010, 25, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M. Determinants of exhibition service quality as perceived by attendees. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2005, 7, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilien, G.L. A descriptive model of the Trade Show budgeting decision process. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1983, 12, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijewski, V.; Yoon, E.; Young, G. How exhibitors select trade shows. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1993, 22, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munuera, J.L.; Ruiz, S.; Hernández, M.; Más, F. Las ferias comerciales como variable de marketing: Análisis de los objetivos del expositor. Inf. Comer. Española 1993, 718, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, D.; Wong, K.S. Exhibiting Strategy and Implementation. Int. J. Advert. 1993, 12, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godar, S.H.; O’connor, P.J. Same time next year-buyer trade show motives. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2001, 30, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gázquez, J.C.; Jiménez, J.F. Las ferias comerciales en la estrategia de marketing. Motivaciones para la empresa expositora. Distrib. Consumo 2002, 66, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel, U.; Voola, R. Travel trade shows: Exploratory study of exhibitors’ perceptions. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2010, 25, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.; Blanco, A.; Díez, F. Exploring the links between goal-setting, satisfaction and corporate culture in exhibitors at international art shows. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2013, 7, 278–294. [Google Scholar]

- Nadège, M.; Cambell-Hunt, C. How SMEs use trade shows to enter global value chains. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2015, 22, 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.H. Industrial and Organizational Marketing; Merrill Publishing Company: Columbus, OH, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, P.; Oromendia, A.; Esteban, L. Measuring the efficiency of trade shows: A Spanish case study. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishna, S.; Williams, J.D. Planning and performance assessment of industrial trade shows: An exploratory study. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1992, 9, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbig, P.; O’Hara, B.; Palumbo, F. Differences between trade show exhibitors and non-exhibitors. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 1997, 12, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seringhaus, F.H.; Rosson, P.J. Firm experience and international trade fairs. J. Mark. Manag. 2001, 17, 877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.F.; Chonko, L.B.; Ponzurick, T.V. A learning model of trade show attendance. J. Conv. Exhib. Manag. 2001, 3, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, G.; Almossawi, M. A study of exhibitor firms at an Arabian gulf trade show: Goals, selection criteria and perceived problems. J. Glob. Mark. 2002, 15, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Bauer, T.; Weber, K. China’s second-tier cities as exhibition destinations. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 22, 552–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Weber, K.; Bauer, T. Dimensions and perceptional differences of exhibition destination attractiveness: The case of China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013, 37, 447–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, J.; Dioko, L.D.; Webber, D.; Zhang, L. Attracting convention and exhibition attendance to complex MICE venues: Emerging data from Macao. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.M.; Gopalakrishna, S.; Smith, P.M. The complementary effect of trade shows on personal selling. Inter. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berné, C.; García-Uceda, M.E. Criteria involved in evaluation of trade shows to visit. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, J.; Webber, D.J. Which exhibition attributes create repeat visitation? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B.; Mair, J. Visitor attendance motivations at consumer travel exhibitions. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Verma, R. Why attend tradeshows? A comparison of exhibitor and attendee’s preferences. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2014, 55, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Weber, K. Exhibition destination attractiveness–organizers’ and visitors’ perspectives. Inter. J. Cont. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2795–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoham, A. Selecting and evaluating trade shows. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1992, 21, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, B. Evaluating the effectiveness of trade shows: A personal selling perspective. J. Pers. Selling Sales Manag. 1993, 13, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dekimpe, M.G.; Francois, P.; Gopalakrishna, S.; Lilien, G.L.; Bulte, C.V. Generalizing about trade show effectiveness: A cross-national comparison. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, S.A. Ten steps to a successful trade show. Mark. Heath Serv. 2002, 22, 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, J.S.; Hsieh, C.; Shen, C. Product innovativeness, trade show strategy and trade show performance: The case of Taiwanese global information technology firms. J. Glob. Mark. 2007, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Marketing resources and performance of exhibitor firms in trade shows: A contingent resource perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 360–370. [Google Scholar]

- Bettis, H.; Cromartie, J.; Johnston, W.; Leila, A. The return on trade show information (RTSI): A conceptual analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2010, 25, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skallerud, K. Structure, strategy and performance of exhibitors at individual booths versus joint booths. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2010, 25, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q. Trade show operation models: Characteristics, process, and effectiveness—Cases from Dongguan. J. China Tour. Res. 2007, 3, 478–508. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, D.; Egan, C.; Wong, K.S. Dimensions of trade show exhibiting management. J. Mark. Manag. 1993, 9, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, D.; Weisgal, M.; Lynagh, P. Integrating exhibit marketing into integrated marketing communications. J. Cons. Mark. 2006, 23, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rosson, P.J.; Seringhaus, F.R. Visitor and exhibitor interaction at industrial trade fairs. J. Bus. Res. 1995, 32, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinallo, D.; Borghini, S.; Golfetto, F. Exploring visitor experiences at trade shows. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2010, 25, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J. Visitor and exhibitor expectations and outcomes at trade exhibitions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 1999, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W.; Korneliussen, T. Managing trade show campaigns: Why managerial responsabilities matter? J. Promot. Manag. 2012, 18, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bello, D.C.; Lohtia, R. Improving trade show effectiveness by analyzing attendees. Ind. Mark. Manag. 1993, 22, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Hama, K.; Smith, P. The effect of successful trade show attendance on future show interest: Exploring Japanese attendee perspectives of domestic and off-shore international events. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2003, 18, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, I.; Qu, H.; Ma, J. Examining the relationship of exhibition attendees’ satisfaction and expenditure: The case of two major exhibitions in China. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2010, 11, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, U.; Brown, M.; Drennan, J. Consumer perceptions of trade show effectiveness. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale For Measuring Consumer Perceived Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, B.; Herbig, P.A. Trade shows: What do the exhibitors think? A personal selling perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 1993, 8, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiter, D.; Milman, A. Attendees’ needs and service priorities in a large convention center: Application of the importance-performance theory. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Lin, C. Exhibitor perspectives of exhibition service quality. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2013, 14, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, S.; Joo, Y. The effects of exhibition service quality on exhibitor satisfaction and behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 683–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, M.; Farhangmehr, M. Grounds of visitors’ post trade fair behavior: An exploratory study. J. Promot. Manag. 2016, 22, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H. The impact of exhibition service quality on general attendees’ satisfaction through distinct mediating roles of perceived value. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 793–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K. The dual motives of participants at international trade shows: An empirical investigation of exhibitors and visitors with selling motives. Int. Mark. Rev. 1996, 13, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, N. The expectations of exhibitors in tourism, hospitality, and the travel industry: A case study on East Mediterranean tourism and travel exhibition. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2005, 7, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.; Law, R.; Tse, T.; Weber, K. Motivation and satisfaction of megabusiness event attendees: The case of ITU Telecom World 2006 in Hong Kong. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Segmentation of boat show attendees by motivation and characteristics: A case of New York National Boat Show. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2009, 10, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmento, M.; Farhangmehr, M.; Simoes, C. Participating in business-to-business trade fairs: Does the buying function matter? J. Conv. Event Tour. 2015, 16, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, J.; Bhalla, N. Factors motivating visitors for attending handicraft exhibitions: Special reference to Uttarakhand, India. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultsman, W. From the eyes of an exhibitor: Characteristics that make exhibitions a success for all stakeholders. J. Conv. Exhib. Manag. 2001, 3, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Mazumdar, T. Product concept demonstrations in trade shows and firm value. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorani, A. Trade-show management. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1996, 37, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, F.; Herbig, P.A. Trade Shows and fairs: An important part of the international promotion mix. J. Promot. Manag. 2002, 8, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; DeSarbo, W.S.; Chen, P.; Fu, Y. A latent structure factor analytic approach for customer satisfaction measurement. Mark. Lett. 2006, 17, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. An examination of determinants of trade show exhibitors’ behavioral intention: A stakeholder perspective. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2630–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Reina, M.; Rufín, R. Calidad de relación entre recinto ferial, expositor y cliente final. Un análisis de las ferias dirigidas al consumidor final. Inf. Comer. Española 2013, 874, 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, S.; Breiter, D. Trade show managers: Profile in technology usage. J. Conv. Exhib. Manag. 2001, 3, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, V.S. Strategies for career planning and development in the Convention and Exhibition industry in Australia. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, J. Virtual exhibitions: A new product of the IT Era. J. Conv. Exhib. Manag. 2002, 4, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Kelley, L.; Gilbert, D.; Al-Shehabi, N.F. Virtual exhibitions: An exploratory study of Middle East exhibitors’ dispositions. Int. Mark. Rev. 2004, 21, 634–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geigenmüller, A. The role of virtual trade fairs in relationship value creation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2010, 25, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, C. Research on designing the official websites of trade shows based on user experience. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2016, 17, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubalcaba, L.; Cuadrado, J.R. Urban hierarchies and territorial competition in Europe: Exploring the role of fairs and exhibitions. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, R.K. Expectations as a comparison standard in measuring service quality: An assessment of a reassessment. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, U.; Lehtinen, J.R. Two approaches to service quality dimensions. Serv. Ind. J. 1991, 11, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owlia, M.; Aspinwall, E. A framework for the dimensions of quality in higher education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 1996, 4, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvin, D.A. Competing on the eight dimensions of quality. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1978, 65, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C.A. Service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E. The marketing of professional services—An organizational dilemma. Eur. J. Mark. 1979, 13, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, N.; Deshmukh, S.G.; Vrat, P. Service quality models: A review. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2005, 22, 913–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avkiran, N. Developing an instrument to measure customer service quality in branch Banking. Int. J. Bank Mark. 1994, 12, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albacete, C.; Fuentes, M.M.; Lloréns, F.J. Service quality measurement in rural accommodation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J. E-service quality: A model of virtual service quality dimensions. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2003, 13, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.; Chiu, H.-C.; Chiang, M.-Y. Maintaining a committed online customer: A study across search-experience-credence products. J. Retail. 2005, 81, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Cheng, C.C.; Ai, C.H. A study of exhibition service quality, perceived value, emotions, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Event Manag. 2016, 20, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Seo, J.; Yeung, S. Comparing the motives for exhibition participation: Visitor’s versus exhibitor’s perspectives. Int. J. Tour. Sci. 2012, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

| Topics | Perspectives | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizer | Exhibitor | Visitor | |

| Exhibition objectives | Lilien (1983) [19], Kijewski et al. (1993) [20], Munuera et al. (1993) [21], Shipley and Wong (1993) [22], Godar and O’connor (2001) [23], Gázquez and Jiménez (2002) [24], Yuksel and Voola (2010) [25], Prado et al. (2013) [26], Nadège and Cambell-Hunt (2015) [27] | Morris (1988) [28] | |

| Exhibition evaluation | Oliver et al. (2015) [29] | Lilien (1983) [19], Munuera and Ruiz (1999) [6] | |

| Exhibition selection | Gopalakrishna and Williams (1992) [30], Kijewski et al. (1993) [20], Herbig et al. (1997) [31], Seringhaus and Rosson (2001) [32], Tanner et al. (2001) [33], Rice and Almossawi (2002) [34], Jin et al. (2010) [35], Jin et al. (2013) [36], Whitfield et al. (2014) [37] | Smith et al. (2004) [38], Berné and García-Uceda (2008) [39], Jin et al. (2010) [35], Whitfield and Webber (2011) [40], Rittichainuwat and Mair (2012) [41], Han and Verma (2014) [42], Jin and Weber (2016) [43] | |

| Participation decision-making | Shoham (1992) [44], Kijewski et al. (1993) [20], O’Hara (1993) [45] | Morris (1988) [28] | |

| Exhibition budget | Morris (1988) [28] | ||

| Performance | Tafesse (2014) [10] | Dekimpe et al. (1997) [46], Friedmann (2002) [47], Chiou et al. (2007) [48], Li (2007) [49], Bettis et al. (2010) [50], Skallerud (2010) [51] | |

| Management | Luo (2007) [52] | Shipley et al. (1993) [53], Tanner et al. (2001) [33], Pitta et al. (2006) [54] | Munuera and Ruiz (1999) [6] |

| Buyer behavior | Rosson and Seringhaus (1995) [55] | ||

| Effectiveness | Munuera and Ruiz (1999) [6], Berné and García-Uceda (2010) [7], Rinallo et al. (2010) [56], Situma (2012) [8], Tafesse (2014) [10] | Gopalakrishna and Williams (1992) [30], O’Hara (1993) [45], Dekimpe et al. (1997) [46], Blythe (1999) [57], Berné and García-Uceda (2010) [7], Yuksel and Voola (2010) [25], Tafesse and Korneliussen (2012) [58], Prado et al. (2013) [26] | Bello and Lohtia (1993) [59], Smith et al. (2003) [60], Zhang et al. (2010) [61], Gottlieb et al. (2014) [62] |

| Sales/buying technique | Lilien (1983) [19], Shipley and Wong (1993) [22] | Bello and Lohtia (1993) [59] | |

| Service quality | Geigenmüller and Bettis-Outland (2012) [9], Adhitya (2019) [11] | Parasuraman et al. (1988) [63], O’Hara and Herbig (1993) [64], Tanner et al. (2001) [33], Jung (2005) [18], Breiter and Milman (2006) [65], Jin and Weber (2013) [43], Lin and Lin (2013) [66], Lee et al. (2015) [67] | Gottlieb et al. (2014) [62], Sarmento and Farhangmenr (2016) [68], Lee (2020) [69] |

| Visiting objectives | Hansen (1996) [70], Munuera and Ruiz (1999) [6], Kozak (2005) [71] | Hansen (1996) [70], Bauer et al. (2008) [72], Park (2009) [73], Sarmento et al. (2015) [74], Nayak and Bhalla (2016) [75] | |

| Exhibitor behavior | Rosson and Seringhaus (1995) [55], Hultsman (2001) [76] | ||

| Exhibitor and visitor profile | Herbig et al. (1997) [31] | Berné and García-Uceda (2008) [39] | |

| Marketing function and strategy | Kirchgeorg et al. (2010) [17] | Pitta et al. (2006) [54], Kim and Mazumdar (2016) [77] | |

| Internal relationships | Poorani (1996) [78], Palumbo and Herbig (2002) [79] | Palumbo and Herbig (2002) [79], Bauer et al. (2008) [72] | |

| Economic impact and benefits | Poorani (1996) [78], Palumbo and Herbig (2002) [79] | Wu et al. (2006) [80], Lee (2020) [69] | |

| Satisfaction | Jung (2005) [18], Lin (2016) [81], Adhitya (2019) [11] | ||

| Relationship between exhibitors and organizers | Rinallo and Golfetto (2011) [5], Jin et al. (2012) [15] | Jin et al. (2012) [15], Rodríguez et al. (2013) [82] | |

| Human resources | Gregory and Breiter (2001) [83], McCabe (2008) [84] | ||

| Virtual exhibition | Edgar (2002) [85], Lee-Kelley et al. (2004) [86], Geigenmüller (2010) [87] | Wu and Wang (2016) [88] | |

| Spatial distribution | Rubalcaba and Cuadrado (1995) [89], Jin and Weber (2016) [43] | ||

| Characteristics | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Companies exhibiting (n = 127) |

| Geographical sample scope | National and International |

| Sample size | 49 companies (objectives/expectations) 54 companies (fulfillment of objectives/perceptions) 54 companies (satisfaction with fair organization) |

| Survey type | Post (objectives/expectations) Personal (fulfillment of objectives/perceptions) Personal (satisfaction with fair organization) |

| Response rate | 38.6% (objectives/expectations) 42.5% (fulfillment of objectives/perceptions) 42.5% (satisfaction with fair organization) |

| Dates field work carried out | 22/4 to 24/5, 2019 |

| Item | Mean (E) | Mean (p) | E/p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Close sales agreements * | 3.3 | 2.6 | E > p |

| 2. Establish new contacts with potential buyers * | 4.1 | 2.9 | E > p |

| 3. Promote company image and improve reputation* | 4.2 | 3.7 | E > p |

| 4. Conduct market research and gather information on competition | 3.2 | 2.8 | E > p |

| 5. Disseminate company information * | 4.3 | 3.7 | E > p |

| 6. Recruit new distributors and sales representatives | 3.1 | 2.8 | E > p |

| 7. Make contact with professionals and specialists who would otherwise be difficult to reach * | 3.6 | 2.8 | E > p |

| Item | Mean |

|---|---|

| 1. Fair facilities (size, design, functionality, conference halls) | 3.4 |

| 2. Parking | 2.9 |

| 3. Cafes, restaurants, etc. | 3.3 |

| 4. Information service and signage | 3.1 |

| 5. Cleanliness | 3.6 |

| 6. Technical services: Assembly, decoration | 3.4 |

| 7. Security | 4.0 |

| 8. Press office | 3.3 |

| 9. Promotion prior to fair | 3.1 |

| 10. Event date | 3.5 |

| 11. Quality and number of exhibitors | 2.8 |

| 12. Quality and number of visitors | 2.7 |

| 13. Professionalism | 3.4 |

| 14. Level of internationalization | 2.7 |

| 15. Attention received from fair stall | 3.9 |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fair facilities | 0.730 | |||

| 2. Parking | 0.727 | |||

| 3. Cafes, restaurants, etc. | 0.705 | |||

| 4. Information service and signage | 0.686 | |||

| 6. Technical services: Assembly, decoration | 0.777 | |||

| 7. Security | 0.811 | |||

| 9. Promotion prior to fair | 0.674 | |||

| 10. Event date | 0.834 | |||

| 11. Quality and number of exhibitors | 0.917 | |||

| 12. Quality and number of visitors | 0.838 | |||

| 13. Professionalism | 0.700 | |||

| 14. Level of internationalization | 0.599 |

| Dependent Variable | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | ANOVA | R2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Sig. | β | Sig. | β | Sig. | β | Sig. | F | Sig. | ||

| PERCEP 1 | 0.028 | 0.807 | 0.477 | 0.000 | 0.147 | 0.197 | 0.362 | 0.002 | 7.522 | 0.000 | 0.380 |

| PERCEP 2 | −0.107 | 0.337 | 0.356 | 0.002 | 0.315 | 0.006 | 0.410 | 0.001 | 8.344 | 0.000 | 0.405 |

| PERCEP 3 | 0.113 | 0.374 | 0.326 | 0.013 | 0.238 | 0.066 | 0.206 | 0.109 | 3.418 | 0.015 | 0.218 |

| PERCEP 4 | 0.178 | 0.183 | 0.157 | 0.238 | 0.154 | 0.248 | 0.272 | 0.044 | 2.224 | 0.080 | 0.154 |

| PERCEP 5 | 0.002 | 0.984 | 0.356 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.974 | 0.385 | 0.003 | 4.224 | 0.003 | 0.275 |

| PERCEP 6 | −0.036 | 0.771 | 0.373 | 0.004 | 0.244 | 0.051 | 0.265 | 0.036 | 4.548 | 0.003 | 0.271 |

| PERCEP 7 | 0.022 | 0.860 | 0.262 | 0.041 | 0.173 | 0.173 | 0.371 | 0.005 | 3.792 | 0.009 | 0.236 |

| Item | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendations (65.6%) | General facilities | 7 | 21.9 |

| Opening hours and days held | 6 | 18.8 | |

| Facilities and installation of stands | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Sq. meter price of stands | 3 | 9.4 | |

| Lack of interest of some contents | 1 | 3.1 | |

| Changes (34.4%) | Visitor quality | 5 | 15.6 |

| Higher level of internationalization | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Higher international promotion | 1 | 3.1 | |

| More orientated to farmers | 1 | 3.1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Guerrero, J.F.; Burgos-Jiménez, J.d.; Tarifa-Fernández, J. Measurement of Service Quality in Trade Fair Organization. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229567

Jiménez-Guerrero JF, Burgos-Jiménez Jd, Tarifa-Fernández J. Measurement of Service Quality in Trade Fair Organization. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229567

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Guerrero, José Felipe, Jerónimo de Burgos-Jiménez, and Jorge Tarifa-Fernández. 2020. "Measurement of Service Quality in Trade Fair Organization" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229567

APA StyleJiménez-Guerrero, J. F., Burgos-Jiménez, J. d., & Tarifa-Fernández, J. (2020). Measurement of Service Quality in Trade Fair Organization. Sustainability, 12(22), 9567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229567