Indigenous Heritage Tourism Development in a (Post-)COVID World: Towards Social Justice at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, USA

Abstract

1. Introduction

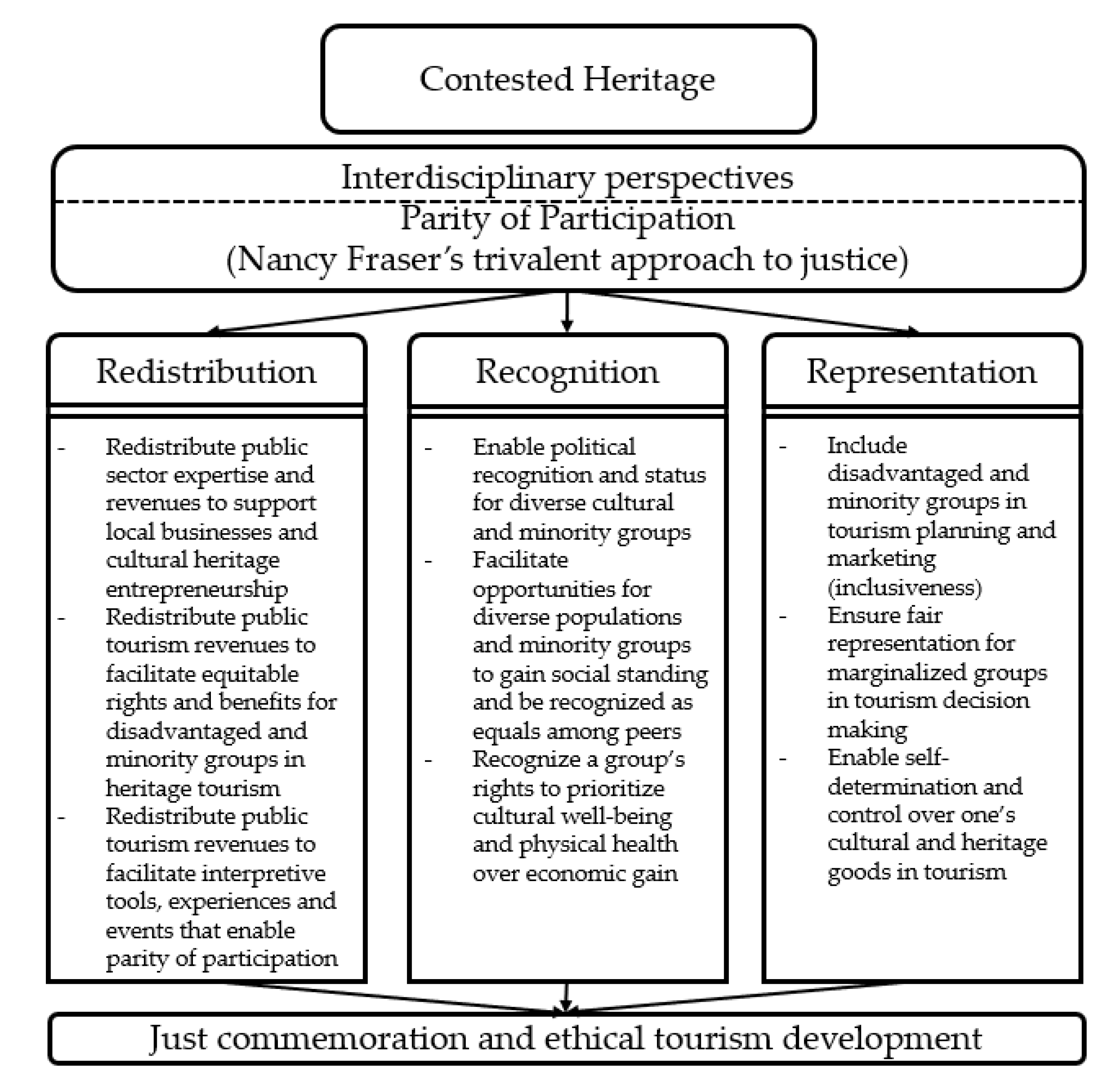

2. Literature Review

2.1. Redistribution

2.2. Recognition

2.3. Representation

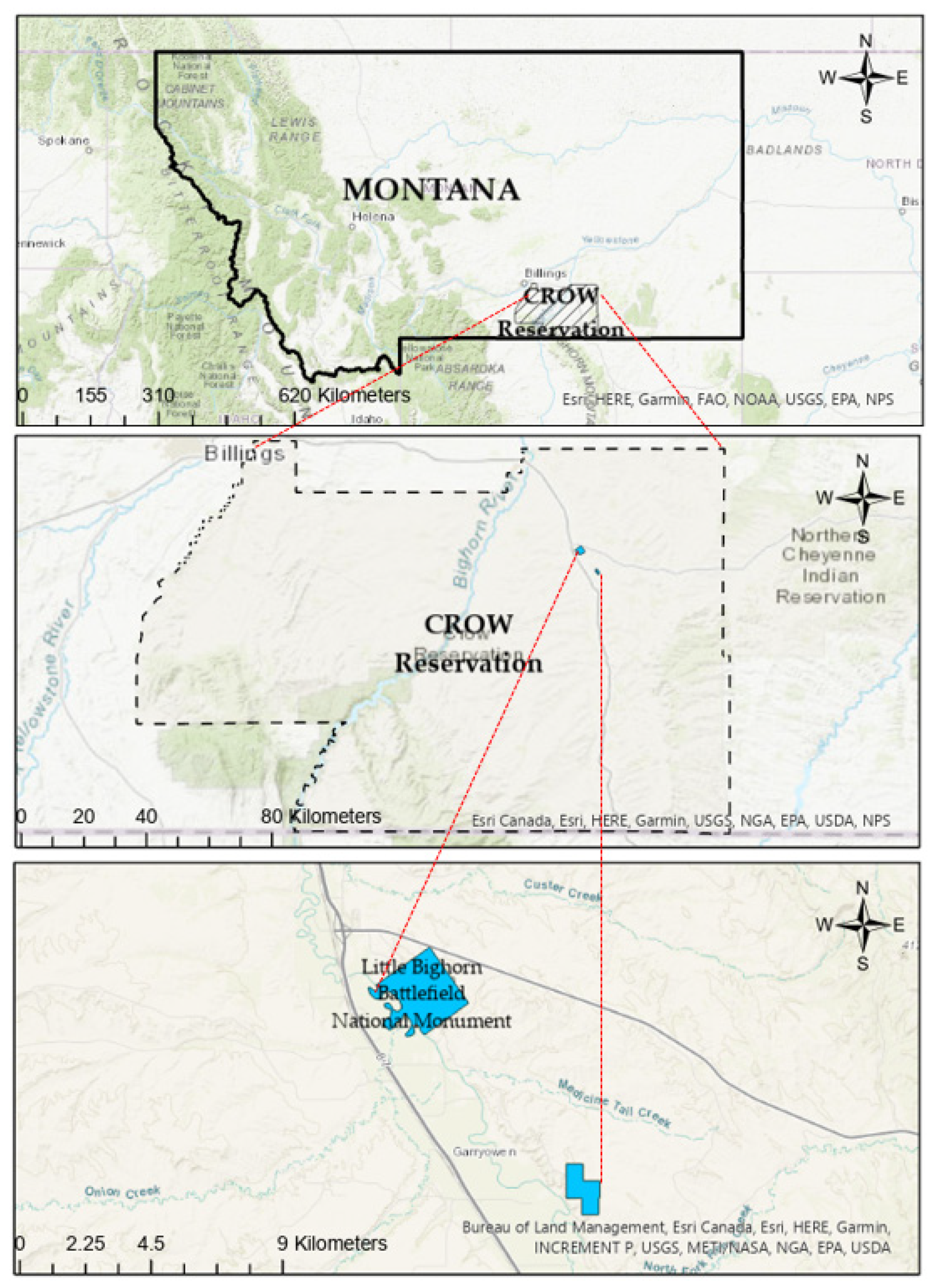

3. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument

3.1. LBH Background and Setting

3.2. The Crow Tribe

- How has heritage tourism activity impacted redistribution, recognition, and representation for the Indigenous people affected by the commemoration and development of LBH?

- How can tourism contribute towards social justice for the Indigenous people impacted by commemoration and tourism at LBH?

3.3. Research Methods

Reflexivity, Positionality, and Decolonizing Approaches

3.4. Findings

3.4.1. Conflict over Commemoration

3.4.2. Redistribution, Recognition, and Representation at LBH

- The Indian Memorial will surprise you… if you didn’t know it, you wouldn’t know it’s there. From the visitor center it appears to be a mound, slightly lifted above the ground. There is already prairie grass sprouting from the outside walls blending it beautifully within its environment.

- When you enter the Memorial, you enter another world—somber, deep, retrospective, and sacred. The Memorial is in the shape of a perfect circle. In the center is a circle of red dirt. Around it is a circled stone walkway. On the inner walls sit panels for each tribe that fought in the battle (Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Arikara). Each tribe lists their dead and there are some pictographs.

3.4.3. Inclusive Indigenous Participation in Tourism at LBH

3.4.4. Complications and Possible Re-Igniting of Conflict Due to COVID-19

3.4.5. Redistribution Measures and Crow Response to COVID-19

4. Discussion

4.1. Redistribution

4.2. Recognition

4.3. Representation

4.4. COVID-19 Challenges

5. Directions Forward: Towards a Trivalent Approach to Justice

5.1. Towards Redistribution

- Redistribute public sector expertise for consultation and involvement with minority communities. Social goods should be redistributed to enable the Crow to participate directly in developing their own tourism enterprises (both with the NPS and independently), and also in marketing their cultural heritage and related community events. Crow tourism operators are primarily small businesses, with less national recognition or reach (unlike LBH/NPS, state entities, other DMOs). Destination marketing efforts by the NPS as well as area and regional destination marketing organizations and others who promote LBH (tour operators, travel writers, etc.) should acknowledge and support Crow businesses participating in tourism and the development of Crow events and visitor experiences. Involvement can also work toward fair representation and control over what goods and images they wish to share, and to help ensure fair distribution of marketing-related resources [99].

- Equitably redistribute public tourism revenues to minority groups involved with heritage tourism. The Crow Tribal Council’s decision to close the reservation to outside visitors and to implement stay-at-home measures was intended to protect community health, but it has also meant less opportunity to perform or, more specifically, to enact cultural recognition and obtain economic benefits from tourism. It should be noted that with the Crow Reservation and tourism operators shut down, they receive no financial compensation for the representation of their cultural heritage at the battlefield. One strategy for addressing this unexpected shortfall could be to redistribute some LBH revenues towards the operations of the Crow bus tour company. The site entry fee could be increased to this end—in 2001, for instance, the site entry fee was increased from USD 6 to USD 10 per car to contribute to help fund construction of the Indian Memorial [100].

5.2. Towards Recognition

- Enable diverse minority and cultural groups to gain status and social standing as equals among peers (a key principle of trivalent justice). The recognition of multiple stakeholders is important here, and participating in interpretive events and other interactive practices facilitates increased recognition and social standing among the visiting public. The battlefield is surrounded by the home of the Crow Tribe, and their unique status of being both American citizens and a sovereign tribal nation must also be recognized.

- At the LBH relationships are needed between different stakeholders, including multiple levels of government (County, State, Federal), tourism operators, DMOs, historical interest groups, area residents, and Indigenous nations affected by the NPS commemoration of Custer’s role to the exclusion of their own role and victory.

- Recognize a group’s rights to prioritize cultural well-being and physical health over economic gain. Other stakeholders must respect the autonomy of Crow decision-making to close the reservation to tourism. State, NPS, and other nontribal entities’ health restrictions (or lack thereof) should not contradict the protective measures of vulnerable Indigenous populations.

5.3. Towards Representation

- Involve minority groups in heritage tourism development and marketing with full recognition of their autonomy, self-determination, and rights to develop and control heritage tourism. The proximity of the Crow Reservation to LBH has made the tribe willing and unwilling participants in tourism activity, and they must be involved in tourism decision-making. For economically marginalized areas like the Crow Reservation, recognition and representation simply cannot be ignored. The Crow should have opportunities to be involved in product development and decisions that affect their cultural heritage and community well-being.

- Ensure fair representation and voice for multiple marginalized groups. Heritage involves the diverse perspectives of different cultural stakeholder groups. The LBH demonstrates that when groups are not involved in developing their own heritage tourism representations, they will contest representations and site management. Recognition, self-determination, autonomy, and control are key towards more just representations of heritage by the cultural group involved, and enables them to challenge other dominant groups’ interpretation of their culture and history.

- Provide new opportunities for tribal involvement in tourism product development. As tourism activity resumes post-COVID-19, opportunities arise for the NPS and tourism industry to better address issues of representation and recognition through heritage tourism products. Increased Crow and other tribal participation in new (socially distanced) digital and audio interpretive products and branding strategies could facilitate visitor learning about the impacts of COVID-19 and other issues on the reservation. This would help to decolonize official interpretations by providing the Crow opportunities for self-expression and world-making.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lanfant, M. Introduction. In International Tourism: Identity and Change; Lanfant, M., Allcock, J., Bruner, E., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fennell, D.; Cooper, C. Sustainable Tourism: Principles, Contexts and Practices; Channel view publication: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.; Kim, H. Bridging the interdisciplinary divide: Towards an integrated framework for heritage tourism research. Tour. Stud. 2005, 5, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Impact Assessment of the COVID-19 Outbreak on International Tourism; United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Bright, C.F.; Foster, K.; Joyner, T.A.; Tanny, O. Heritage tourism, historic roadside markers and “just representation” in Tennessee, USA. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannam, K. Contested representations of war and heritage at the Residency, Lucknow, India. Int. J. Tour. 2006, 8, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hollinshead, K. White gaze, ‘red’ people—Shadow visions: The disidentification of ‘indians’ in cultural tourism. Leis. Stud. 1992, 11, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, E. “To Take Their Heritage in Their Hands”: Indigenous Self-Representation and Decolonization in the Community Museums of Oaxaca, Mexico. Am. Indian Q. 2006, 30, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Scales of justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blue, G.; Rosol, M.; Fast, V. Justice as Parity of Participation: Enhancing Arnstein’s Ladder Through Fraser’s Justice Framework. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation. In Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange; Fraser, N., Honneth, A., Eds.; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 7–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T. Justice and Ethics in Tourism; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, T.J. Tourism and agricultural development in Thailand. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 877–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Tisch-Rottensteiner, A. Authenticity versus development: Tourism to the hill tribes of Thailand. In Controversies in Tourism; Moufakkir, O., Burns, P.M., Eds.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012; pp. 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dwijayanthi, P.T.; Jones, K.; Ayu, N.G.; Satyawati, D. Indigenous People, economic Development and Sustainable Tourism: A Comparative Analysis between Bali, Indonesia and Australia. Udayana J. Law Cult. 2017, 1, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sangchumnong, A.; Kozak, M. Sustainable cultural heritage tourism at Ban Wangka Village, Thailand. Anatolia 2018, 29, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbor, L.C.; Hunt, C.A. Indigenous tourism and cultural justice in a Tz’utujil Maya community, Guatemala. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Eagles, P.F.J. An integrative approach to tourism: Lessons from the Andes of Peru. J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.L. Interrogating the equity principle: The rhetoric and reality of management planning for sustainable archaeological heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, J.S.; Kieti, D. Tourism and socio-economic development in developing countries: A case study of Mombasa Resort in Kenya. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Xu, K. Tourism-Induced Livelihood Changes at Mount Sanqingshan World Heritage Site, China. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Poudyal, N.C. Developing sustainable tourism through adaptive resource management: A case study of Machu Picchu, Peru. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 917–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G. Community participation in tourism at a world heritage site: Mutianyu great wall, Beijing, China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.-C.; Chia-Hao, L.; Chang, H.-M. Does Tourism Development Bring Positive Benefit to Indigenous Tribe? Case by Dongpu in Taiwan. Adv. Res. 2015, 4, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, C.; Lilley, I. Who Benefits? World Heritage and Indigenous People. Herit. Soc. 2017, 10, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Campbell, G. The Tautology of “Intangible Values” and the Misrecognition of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Herit. Soc. 2017, 10, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L. The recognition and misrecognition of community heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. ‘We are… we are everything’: The politics of recognition and misrecognition at immigration museums. Museum Soc. 2017, 15, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L. Heritage-making and political identity. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2007, 7, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.F.; Menzies, C.R. Traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous tourism. Tour. Indig. Peoples Issues Implic. 2007, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.; Marwood, K. Action heritage: Research, communities, social justice. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. Why Love, Care and Solidarity Are Political Matters: Affective Equality and Fraser’s Model of Social Justice’. In Love: A Question for Feminism in the Twenty-First Century; Jónasdóttir, A.G., Ferguson, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 173–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, J.H.; Stein, T.V. Participation, power and racial representation: Negotiating nature-based and heritage tourism development in the rural south. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2007, 20, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.C.H. The meanings of a heritage trail in Hong Kong. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 570–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niskala, M.; Ridanpää, J. Ethnic representations and social exclusion: Sáminess in Finnish Lapland tourism promotion. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, G. Selling culture? Between commoditisation and cultural control in Indigenous alternative tourism. Pasos. Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2014, 12, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, M.F. The breath of the mountain is my heart: Indigenous cultural landscapes and the politics of heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnoni, A.; Ardren, T.; Hutson, S. Tourism in the Mundo Maya: Inventions and (mis)representations of Maya identities and heritage. Archaeologies 2007, 3, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Zygadlo, F.K.; Matunga, H. Rethinking Maori tourism. Asia Pacific J. Tour. Res. 2004, 9, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoamo, M. Māori tourism: Image and identity—A postcolonial perspective. Ann. Leis. Res. 2007, 10, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoamo, M.; Thompson, A. (re)Imaging Māori tourism: Representation and cultural hybridity in postcolonial New Zealand. Tour. Stud. 2010, 10, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Lee, S. Ethical Issues in Tourism. In The SAGE Handbook of Marketing Ethics; Eagle, L., Dahl, S., Pelsmacker, P., Taylor, C., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. Ethnic tourism and cultural representation. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 561–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemelin, R.H.; Whyte, K.P.; Johansen, K.; Desbiolles, F.H.; Wilson, C.; Hemming, S. Conflicts, battlefields, indigenous peoples and tourism: Addressing dissonant heritage in warfare tourism in Australia and North America in the twenty-first century. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasson, B. Commemorating the Anglo-Boer war in post-apartheid South Africa. Radic. Hist. Rev. 2000, 78, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M. Cultural heritage and Indigenous tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, K. Cultural Tourism: Exploration or Exploitation of American Indians? Am. Indian Law Lev. 2001, 26, 223–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piner, J.; Paradis, T. Beyond the casino: Sustainable -tourism and cultural development on native american lands. Tour. Geogr. 2004, 6, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service. Foundational Document: Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Montana, 2015. Available online: http://npshistory.com/publications/foundation-documents/libi-fd-2015.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Greene, J. Stricken Field: The Little Bighorn since 1876; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Park Serviec. Park Statistics, 2017. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/management/statistics.htm (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Montana Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs. Crow Nation, 2020. Available online: https://tribalnations.mt.gov/crow (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Crow Tribal Council. Crow Reservation Demographic and Economic Information, 2013. Available online: https://lmi.mt.gov/Portals/193/Publications/LMI-Pubs/LocalAreaProfiles/Reservation%20Profiles/RF13-Crow.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Churchill, W. Struggle for the Land: Native North American Resistance to Genocide, Ecocide and Colonization; City Lights: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grinde, D.; Johansen, B. Ecocide of Native America: Environmental Destruction of Indian Lands and People; Clear Light Publishers: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Congress of American Indians. Demographics, 2020. Available online: http://www.ncai.org/about-tribes/demographicsndians,N.C.ofA.Demographics (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Kim, S. Native Americans are more Vulnerable to Coronavirus—Less Than 3 Percent have been Tested. Newsweek, 21 May 2020. Available online: https://www.newsweek.com/native-americans-are-more-vulnerable-coronavirusless-3-percent-have-been-tested-1505688 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- St. Pierre, N. Listening to the student voice: A case study of the Little Big Horn College Mission. Ph.D. Thesis, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Swanke, D. Little Bighorn Battlefield Update—Fall 2013; National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. Available online: https://custerbattlefield.org/wp1/pdfs/update-fall-2013.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Samuels, I. COVID-19 Spread Forces Lockdown on Crow Reservation. Great Falls Tribune, 7 August 2020. Available online: https://www.greatfallstribune.com/story/news/2020/08/07/covid-19-spread-forces-lockdown-crow-reservation-montana/3324228001/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Mayer, L. Checkpoints Set up on Crow Reservation to Prevent Spread of COVID-19. Billings Gazette, 29 March 2020. Available online: https://billingsgazette.com/news/local/checkpoints-set-up-on-crow-reservation-to-prevent-spread-of-covid-19/article_bf6cbc27-3dbd-5823-bbfc-0e20de6830cc.html (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Cases in the U.S.. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Ling, J. Indigenous Nations Battle to Secure Borders, Funds amid Pandemic. Foreign Policy, 6 August 2020. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/08/06/coronavirus-pandemic-indigenous-nations-secure-borders-funds/ (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, J. Commemoration and contestation: The Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, USA. In Justice and Ethics in Tourism; Jamal, T., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Darder, A. Decolonizing interpretive research: Subaltern sensibilities and the politics of voice. Qual. Res. J. 2018, 18, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 2nd ed.; Zed books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, M.J.; Grimwood, B.S.R.; Caton, K. Becoming common plantain: Metaphor, settler responsibility, and decolonizing tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miscellaneous National Park Legislation: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Public Lands, National Parks and Forests of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (S. Hgr. 102–468), U.S. Senate, 102nd Cong., 1991. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?printsec=frontcover&vq=custer&id=GefZQAghKYcC&output=text (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Reece, B. The story of the Indian Memorial, 2003. Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield. Available online: http://www.friendslittlebighorn.com/Indian%20Memorial.htm (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Olp, S. Ceremony Marks Completion of Indian Memorial on Anniversary of Little Bighorn Battle. Billings Gazette, 5 September 2014. Available online: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/ceremony-marks-completion-of-indian-memorial-on-anniversary-of-little-bighorn-battle/article_fbe0c5ec-0639-5df2-9ccc-ed7ab209f3a8.html (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Meadow, J. 127 years later, the other side speaks—10,000 to dedicate Indian memorial at Little Bighorn today. Rocky Mountain News, 25 June 2003. Available online: https://infoweb-newsbank-com.srv-proxy2.library.tamu.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=NewsBank&t=&sort=YMD_date%3AD&page=3&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=2003%20-%202003&fld-base-0=alltext&maxresults=20&val-base-0=%22indian%20memorial%22%20%27little%20bighorn%22&docref=news/0FBEB4CE84927240 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Reece, B. History of the Warrior Markers, 2008. Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield. Available online: http://www.friendslittlebighorn.com/warriormarkershistory.htm (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Charles, J. Superintendent’s Annual Narrative Report, 2007. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Available online: http://www.friendslittlebighorn.com/SuperintendentsAnnualReport2007.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Hammond, K. Superintendent’s Annual Narrative Report, 2009. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Available online: http://www.friendslittlebighorn.com/littlebighornsuptannualreport2009.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Utley, R. Whose shrine is it? The ideological struggle for Custer Battlefield. Montana 1992, 42, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. Controversy over memorial to winners at Little Bighorn. New York Times, 24 August 1997. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/1997/08/24/us/controversy-over-memorial-to-winners-at-little-bighorn.html?ref=georgearmstrongcuster (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- Woody, K. Custer revisited. Nat. Hist. 2016, 124, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Olp, S. Tribal tour company tells story of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Billings Gazette, 10 June 2015. Available online: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/montana/tribal-tour-company-tells-story-of-the-battle-of-the-little-bighorn/article_55596702-bae2-5a93-ac0d-c76561b5c957.html (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Kordenbrock, M. Crow Tribe orders quarantine and curfew. Billings Gazette, March 2020. Available online: https://billingsgazette.com/news/local/crow-tribe-orders-quarantine-and-curfew/article_53dda9f4-735c-5bfc-93de-ada6a700fcd6.html (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- National Park Service. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument is Modifying Operations to Implement Local Health Guidance, 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/NPSLIBI/ (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- McLaughlin, K. Montana’s Tribal Nations Preserve COVID Restrictions to Preserve their Cultures. Kaiser Health News, 5 June 2020. Available online: https://khn.org/news/montanas-tribal-nations-preserve-covid-restrictions-to-preserve-their-cultures/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Crow Tribe of Indians. Executive Order of Chairman Not Afraid, 2020. Official CTI News. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/OfficialCTINews/ (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Leeds, T. Bullock: Uptick in COVID cases stresses need to take precautions. Havre Daily News, 18 June 2020. Available online: https://www.havredailynews.com/story/2020/06/18/local/bullock-uptick-in-covid-cases-stresses-need-to-take-precautions/529393.html (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- State of Montana. Reopening the Big Sky: Phased Approach, 2020. Available online: https://covid19.mt.gov/Portals/223/Documents/Reopening%20Montana%20Phase%202.pdf?ver=2020-05-20-142015-167 (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- National Park Service. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument Is Beginning to Increase Recreational access to Park Grounds, 2020. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/NPSLIBI/ (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Henson, C.; Hill, M.; Jorgensen, M.; Kalt, J. Federal COVID-19 Response Funding for Tribal Governments: Lessons from the CARES Act. (Policy Brief No. 5), 2020. Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development Native Nations Institute. Available online: https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/policy_brief_5-cares_act_lessons_24july2020_final_for_dist.pdf?m=1595612547 (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Page, C. COVID-19 relief checks handed out at Crow Agency causes confusion. Billings Gazette, 2 July 2020. Available online: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/covid-19-relief-checks-handed-out-at-crow-agency-causes-confusion/article_282ec640-21ba-5301-8faa-aef3cada7f86.html (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Hamby, P. Checks and checkpoints: Crow and Northern Cheyenne Fighting COVID. Billings Gazette, 13 July 2020. Available online: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/checks-and-checkpoints-crow-and-northern-cheyenne-fighting-covid/article_5b37090f-760d-5abf-b569-a7c4563ed587.html (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Montana Department of Commerce. Montana Coronavirus Relief Grant Awards, 2020. Available online: https://commerce.mt.gov/Montana-Coronavirus-Relief/Awarded-Grants (accessed on 19 August 2020).

- Hammond, K. Superintendent’s Annual Narrative Report, 2008. Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. Available online: https://www.friendslittlebighorn.com/2008superintendentsannualreport.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Block, M. Little Bighorn Battlefield memorial dedicated [Radio Broadcast Transcript]. All Things Considered, 25 June 2003. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=n5h&AN=6XN200306252006&site=eds-live (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Fish, L. A new Day Dawns at Little Bighorn. Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 June 2003. Available online: https://infoweb-newsbank-com.srv-proxy1.library.tamu.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&t=pubname%3APHIB%21Philadelphia%2BInquirer%252C%2BThe%2B%2528PA%2529&sort=YMD_date%3AD&page=1&fld-base-0=alltext&maxresults=20&val-base-0=%22little%20bighorn%22&docref=news/0FBE980F233C6F44 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Sukut, J. Crow Fair Cancelled, Stay at Home Order Extended on the Reservation. Billings Gazette, 16 July 2020. Available online: https://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/crow-fair-canceled-stay-at-home-order-extended-on-the-reservation/article_e15eb471-303b-5da1-bfe2-5eca9186f4cf.html (accessed on 23 September 2020).

- Whiting, F. Crow Tribe Stay-at-Home Order Extended, Crow Fair Canceled. Sheridan Media, 16 July 2020. Available online: https://sheridanmedia.com/news/23753/crow-tribe-stay-at-home-order-extended-crow-fair-canceled/ (accessed on 23 September 2020).

- Repanshek, K. Coping with coronavirus: Phased opening coming to National Parks. National Parks Traveler, 29 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal, T.; Camargo, B.A. Sustainable tourism, justice and an ethic of care: Toward the Just Destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gildart, B. History revisited at the infamous Little Bighorn. Native Peoples Magazine, July/August 2001; 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Duffy, R. The Ethics of Tourism Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, K.P. An environmental justice framework for indigenous tourism. Environ. Philos. 2010, 7, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wahl, J.; Lee, S.; Jamal, T. Indigenous Heritage Tourism Development in a (Post-)COVID World: Towards Social Justice at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, USA. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229484

Wahl J, Lee S, Jamal T. Indigenous Heritage Tourism Development in a (Post-)COVID World: Towards Social Justice at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, USA. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229484

Chicago/Turabian StyleWahl, Jeff, Seunghoon Lee, and Tazim Jamal. 2020. "Indigenous Heritage Tourism Development in a (Post-)COVID World: Towards Social Justice at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, USA" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229484

APA StyleWahl, J., Lee, S., & Jamal, T. (2020). Indigenous Heritage Tourism Development in a (Post-)COVID World: Towards Social Justice at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, USA. Sustainability, 12(22), 9484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229484