Abstract

Mobile devices are more present in our everyday lives and have become an important factor in travel behavior. This study amends the technology acceptance model (TAM) and employs it to discuss the relationship between overseas independent travelers using a smartphone travel application (APP) and perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, usage attitude, usage intentions, and information search behavior. As such, the results reveal that foreign independent travelers (FIT) have a positive usage attitude toward the APP and this produces positive usage intention. The findings herein show that one can apply the new TAM to the tourism industry, as the results not only offer research and development avenues for production ideas, but also present references for formulating new APP policies and strategies.

1. Introduction

The rise of smartphones in combination with other mobile communication devices and wireless transmission technologies has helped travelers to conduct a variety of tourism information search behaviors at any time, in any place, and with a variety of methods. Brown and Chalmers [1] note that with the advancement of mobile phone technology, sightseeing tourism has become a popular venue for the usage of mobile phone information systems. The U.S. market research organization eMarketer [2] notes that the Asia Pacific region has the highest rate of smartphone penetration in the world, and within this region, Taiwan’s smartphone penetration rate is 73.4%, or the highest in the world. Additionally, Taiwan’s Ministry of Transportation and Communications’ (MOTC) Tourism Bureau [3] points out that Taiwanese foreign trips received 32% growth in outbound foreign tourism over four years. According to the Institute for Information Industry (IFII) [4], 66.9% of Taiwanese people use smartphones in their daily lives to search for maps or book airline tickets when traveling. There is growing emphasis on combing the technology and applications with travel and this has gradually changed the travel model for current travelers [5,6]. It is now quite common for smartphone users to download applications (APPs), and tourism-type APPs are popular. While overall the mobile evolution has contributed to enhancing the travel factor at large, only little is known about how it has affected the on-the-go travel experience. Likewise, travelers search for information to help them decide visiting new attractions or trying certain activities at the destination [7]. For this reason, it is necessary to understand the characteristics of smartphone application (APP) use among FITs, and the items and types of things that travelers search for when using smartphone tourism APPs.

Davis et al. [8] set up the technology acceptance model (TAM) in order to assess and forecast the degree of user acceptance of information technology (IT) systems and to understand for what reasons people would accept or reject using IT systems. Davis et al. [1] further separate the beliefs of individuals in TAM into perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. These two factors include users’ attitudes toward new technologies that in turn impact their inclinations for utilizing such technologies. Examining these factors could provide empirical evidence to facilitate effective tourism development planning as well as enhance travelers’ experiences. Therefore, our study shall amend TAM, as Davis et al. [8] propose, by eliminating external variables and real usage behavior variables from the model and introducing a new variable termed information search behavior. This study uses the new model to explore the correlation between Foreign Independent Travelers’ perceived usefulness and their perceived ease of use of smartphone tourism APPs via usage intention and information search behavior. The objectives of this study are as follows.

- Explore the characteristics of Foreign Independent Travelers who use smartphone tourism APPs.

- Analyze the items and types of things that Foreign Independent Travelers search for on smartphone tourism APPs.

- Present the effects of the use of smartphone tourism APPs on the information search behavior of Foreign Independent Travelers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Foreign Independent Travelers (FIT)

Lin [9] notes that independent tourism emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries when aristocrats in Europe and England’s Victorian Era conducted “grand tours”. In the early 19th century, young members of the working classes began “tramping” or traveling in search of work or education. This practice is seen as the origin of modern independent tourism or “backpacking.” Taiwan’s Tourism Bureau defines a foreign independent traveler (FIT) as small groups or individuals who travel to foreign countries. Stebbins [10] argues that independent tour emphasizes a type of in-depth tourism, whereby travelers immerse themselves in the culture and lifestyle of their destinations and also place importance on self-inspiration. Lin [9] notes that independent travelers have the characteristics of viewing tourism as the focus of life and emphasizing cognitive growth, self-exploration, uniqueness, and identity. Initially, the acronym FIT stood for “foreign independent traveler”, but now it is also commonly used to describe fully/frequent/free independent travelers. FITs do not travel with group tours or according to any schedule imposed by others; these travelers almost always design their own itineraries and arrange their own travel plans. Taiwan’s MOTC Tourism Bureau [3] states that when Taiwanese people travel abroad, 65.7% choose to travel independently. Thus, we choose foreign independent travelers as the object of this study.

2.2. Smartphones and Tourism APPs

Application (APP) is a generic term used for any type of software that uses operating systems as their own operating platforms. More than half of Taiwanese people who have smartphones download APPs for use on Apple’s iOS or Google’s Android operating system. The commonly used tourism APPs include Google Maps, Yahoo Maps, Pack & Go Deluxe, TripCase, iHotel, RockCat Studio Translate, and Travel Book. IFII [4] notes that the three key scenarios for smartphone use are travel, watching television, and ordinary shopping; in fact, 66.9% of users employ smartphone tourism APPs to search for maps or book plane tickets during their travels. Smartphones provide basic phone functions and also offer the ability to use Wi-Fi, GPS, camera, and internet. These functions allow users to conduct a variety of tourism information search services and commercial behaviors at any time and in any place, by using a variety of methods. Recent tourism APPs focus more on travel information, travel itineraries, and hotel bookings [6]. Bazazo et al. [11] indicated that the impact of smartphone and APPs on tourism contributes to pushing the development of tourism wheel for tourists and to achieving an increase in the growth rates for tourism sites. The use of smartphones by travelers in constantly increasing which in turn gives the opportunity for promoting the marketing and services of tourism [12]. By end-2016, Taiwan’s smartphone penetration rate had hit 73.4% [3]. The smartphones can give FITs better access to research on travelling information; they also get travel inspiration from photos, videos, and online reviews. As such, we choose to conduct research related to smartphones and APP usage in this study.

2.3. Technology Acceptance Model

If IT systems cannot be adopted by people, then Davis et al. [8] argue that these systems are of no use for improving organizational performance. As such, Davis et al. [8] build TAM and use it to assess and forecast users’ acceptance of IT system tools and to investigate what reason would push people to accept or reject IT systems. Ever since the arrival of TAM, some academics have studied and amended the original model and strengthened its explanatory power. Liang and Yeh [13] amended TAM by changing perceived usefulness to perceived entertainment, thus allowing them to understand whether users have different feelings towards smartphone games in different environments and locations. Kim et al. [14] utilize TAM to explore acceptance behavior toward hospitality industry information management systems, include a new variable (perceived value), and explore the information quality of an information management system and the effects of system quality and service quality on beliefs. Morosan [15] uses TAM to explore the utilization of biometric systems (fingerprints and iris scans) by hotels and includes perceived innovation as a new variable in TAM. In their study of airline e-ticketing services, Lee and Wan [16] incorporate the new variables of functional confidence and familiarity in the original model in order to determine whether travelers from China are able to accept airline e-ticketing services. Oh et al. [17] combine TAM with information and communication technologies to explore the use of mobile technology products by travelers when searching for tourism information. The results of their survey show that this model is capable of effectively forecasting travelers’ usage intentions and their use of mobile technology. We suggest that this model is suitable for use in tourism and hospitality industries. In summary of the above literature findings for which the fit, reliability, and validity of TAM when applied to the tourism industry are all highly suitable, our study adopts it as the research framework. With TAM as the basis, this study eliminates the external and real usage behavior variables in the model and introduces a new variable, information search behavior. This study takes this new model to explore the level of use of APPs by Foreign Independent Travelers when searching for tourism information with new smartphone technologies.

2.4. Information Search Behavior

Loudon et al. [18] state that information collection is the act of individuals searching for and processing psychological and physical information for decision-making purposes. Solomon [19] further argues when consumers face a question related to consumption that they require relevant information to help them make consumption decisions. This type of behavior, in which individuals search for appropriate information, is referred to as information searching. Wang [20] defines the process of searching online for necessary information as web information seeking. Fodness and Murray [21] note that tourism information is information that travelers search for or receive before or after their travels; this includes information related to travel, room and board, itinerary planning, and tourism activities. Taiwan’s MOTC Tourism Bureau [22] states that most of the public’s tourism information comes from close friends (53%), followed by the internet (37%). After the emergence of the smartphone age, people are able to conduct a variety of tourism information search behaviors at any time and from any place under a variety of methods. Employing smartphones’ tourism APPs is quite convenient and provides travelers with the ability to search for information related to transportation, housing, food, maps, points of interest, exchange rates, shopping, and city overviews. In summary of the above findings, foreign independent travelers often search for a large amount of tourism information in order to reduce any potential risks encountered while traveling. For this reason, this study uses an updated TAM to explore Foreign Independent Travelers’ perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, usage attitude, and usage intentions when using smartphones. We further investigate the extent to which users utilize smartphone APPs to conduct information search behavior after exhibiting usage intention.

3. Research Framework and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Research Framework

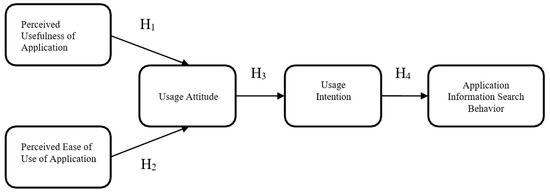

This study takes TAM, proposed by Davis et al. [8], as its basis in order to eliminate external variables and real usage behavior variables and includes a new variable for information search behavior. We illustrate this revised version of TAM in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Modified technology acceptance model (TAM) framework.

3.2. Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use

Davis et al. [8] state that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use both directly impact usage intention through the influence of usage attitude. If users can interact with a technological system more easily, then their perceived effectiveness towards [23] and ability to control [24] the technology system are very good, and so they are better able to operate the system. Therefore, we determine that perceived ease of use positively affects usage attitude. The studies of Morosan [15] and Holden and Karsh [25] both argue that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use significantly and positively impact usage attitude. These studies’ results show that when users are confident that the adoption of new technologies helps improve their work performance, they exhibit more positive usage attitudes for adopting these new technologies. If users perceive that a new technology is easier to learn and that they do not need to exert much effort on the technology, then they have a more positive usage attitude towards adopting this technology. In summary, we propose Hypotheses 1 and 2.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The perceived usefulness of Foreign Independent Travelers towards a smartphone application positively affects usage attitude.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The perceived ease of use of Foreign Independent Travelers towards a smartphone application positively affects usage attitude.

3.3. Usage Attitude

Attitude is an individual’s persistent assessment of a preference for or against a thing or idea, and it is an emotional feeling [26]. Davis et al. [8] argue that usage attitude directly affects usage intention, meaning that users’ real usage behaviors are determined by usage intention, and that their usage intentions are determined by their individual usage attitude. The idea that usage attitude affects usage intention is a common theme among many academics [27]. Heberlein and Black [28] argue that if usage attitude and usage intention are more specific, then the relationship between the two is more distinct. The above findings show that if users have a more positive usage attitude towards a system, then they will have a higher usage intention towards its. In summary, we propose Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The usage attitude of Foreign Independent Travelers towards smartphone APPs positively affects usage intention.

3.4. Usage Intention

Usage intention defines the degree to which an individual is willing to engage in a particular behavior. When individuals’ usage intention is stronger, the probability that they will actually engage in that behavior is higher, and so usage intention and real behaviors present a strong direct correlation. Usage intention is the best variable for predicting an individual’s behavior [29]. Bloch et al. [30] separate information collection into pre-purchase search and ongoing search. The former denotes search behavior conducted by consumers with the goal of making better purchasing decisions, while the latter refers to search behavior conducted by consumers with the goal of increasing their knowledge for future decision making. The objective of pre-travel information searches conducted by independent travelers is to improve decision making related to their itinerary content; conversely, the objective of ongoing information searches by travelers is to increase their knowledge in order to cope with a variety of future decisions. The new TAM established herein argues that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use affect usage attitude, and that usage attitude impacts usage intention. The aim of this study is to understand whether usage intention affects information search behavior exhibited by smartphone application users. In summary of the above, we propose Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Foreign independent travelers’ usage intention towards a smartphone APP significantly affects their information search behavior on that APP.

4. Research Methods

4.1. Questionnaire Design and Operational Definitions

This research utilized the new TAM to explore why Foreign Independent Travelers (FIT) use smartphone APPs to conduct tourism information search behaviors. As such, we amended the questionnaires developed by Lee and Wan [16], Liang and Yeh [13] and Hella and Krogstie [31] for use in this study. Table 1 lists the operational definition of each research variable. Our study’s measurement method involved asking respondents their level of agreement with the questionnaire items. We used a 7-point Likert scale for question items related to perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, usage intention, and information search behavior. This scale ranged from 7 points (strongly agree) to 1 point (strongly disagree). With regard to questions related to the usage attitude variable, we used a semantic differential in order to determine the cognitive meaning of words and concepts and employed a bipolar scale consisting of two opposing adjectives in order to assess any concept, with subjects’ marks representing the direction and intensity of their emotion. Herein, there was no numerical or textual explanation, and points were assigned on a scale from 1 to 7. Then, the study invited three expert scholars in the field of tourism to review the questionnaire for the content validity; and the research questionnaire has a total of 44 questions.

Table 1.

Definitions of variables.

4.2. Sampling Design and Data Analysis

The subjects of this study are Taiwanese FITs aged 18–65, who have used smartphone APPs prior to or during their travels in order to search for tourism information for their most recent trip. This study adopts the convenience sampling method and questionnaires distributed at Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport during December 2012–March 2013. The target population is Taiwanese FITs, thus a paper questionnaire was designed in a Traditional Chinese language version. More than 1000 Taiwanese FITs were randomly intercepted at arrival terminals of Taoyuan International Airport, with the screening question regarding smartphone APPs use for information searches associated their most recent trip. Because this study focused primarily on smartphone owners, particularly those who had used their smartphones for information searches related to recent trip abroad, travelers who reported that they did not own a smartphone were excluded from analysis. In this study we utilized SPSS and AMOS to conduct data analysis. Structural equation modeling (SEM) helped us to examine the causal relationship between the model’s variables, to interpret the model, and to test research hypotheses.

5. Empirical Analysis

A paper questionnaire survey was distributed randomly at arrival terminal of Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport. Using the convenience sampling method to distribute questionnaires, ultimately data from 400 respondents were retained. After eliminating 24 erroneously completed or incomplete questionnaires, our valid sample included 376 questionnaires, for a valid return rate of 94%. Over half of the sample subjects are female, and the largest age group covers those who are 18–25 years old. The most prevalent education level is university, and the most dominant overall independent travel budget is under NT$30,000. The most typical region of travel is Asia (including countries such as Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Macau), while the most common duration of travel is 4–6 days, as shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Sample data analysis.

5.1. Analysis of Smartphone Usage Characteristics

We note that 25.5% of FITs use smartphones an average of 1–3 h per day, 24.7% use smartphones 3–6 h per day, and 27.7% use smartphones 6–10 h per day. With regard to the location of their information search behavior, 83% of Foreign Independent Travelers use their smartphones in their home country prior to travel to search for tourism information, while 68.4% search for such information abroad during their travels, and 51.4% do both. The most common search items are information related to transportation, maps, and points of interest. Smartphone application items that Foreign Independent Travelers most commonly believe should be improved are information related to maps, transportation, food and drink, and points of interest. These travelers further believed that the variety of usable APPs was insufficient, the content was too simple, and that downloads have to be paid for, as Table 3 lists.

Table 3.

Smartphone usage characteristics.

5.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

Reliability denotes the consistency and stability of measurement results and is commonly measured by using the Cronbach’s α value. If Cronbach’s α is larger, then the reliability of research variables is greater. The Cronbach’s α values of the variables in this study are between 0.826–0.884, and as such all meet the Cronbach’s α standard of 0.7 and above, indicating that the research variables herein all have good reliability. Generally speaking, the reliability, consistency, and stability of this questionnaire are high, as presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Reliability and validity analysis.

Validity represents the accuracy, reliability, and effectiveness of measurement results as well as the degree to which the measurement instruments are capable of measuring the questions that researchers aim to quantify. This study used convergent validity to measure the multiple questions developed from single variables in the returned questionnaires and to determine whether these questions converge to a single factor. One can generally test convergent validity by using average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and factor loading. According to Nunnally [32], if AVE > 0.5, CR > 0.7, and factor loading > 0.5, then the research variables exhibit good convergent validity. After eliminating questionnaire questions with factor loadings below 0.5 (PE6, PE7, and IS4), each research variable has AVE > 0.5, CR > 0.7, and factor loading > 0.5, as Table 4 lists. This indicates that our study’s research variables have good convergent validity.

5.3. Path Analysis

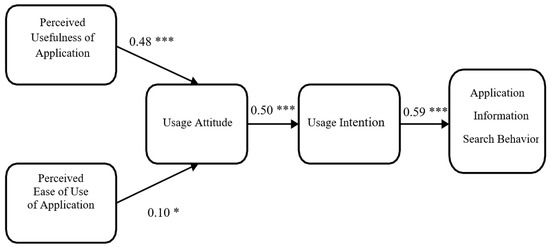

5.3.1. Analysis of All Users

In this study, we used SEM to calculate path coefficients, and standardized regression coefficient estimates, critical ratios, and p-values appear in Table 5 and Figure 2. From Table 5 and Figure 2, we see that when the perceived ease of use of an APP corresponds to usage attitude, the pathway coefficient is 0.10 and that the standardized regression coefficient estimate (0.110) is excessively small, indicating that the influence of this variable is relatively weak. Furthermore, the critical ratio (2.208) is between 1.95–2.58, and the p-value (0.027) is <0.05, showing that the variable relationship is significant. Other variable relationships all exhibit good and significant influences. For this reason, this study declares that H1, H2, H3, and H4 are all supported, and only H2 exhibits a relatively weak relationship.

Table 5.

Structural equation model (SEM) analysis.

Figure 2.

Path relationships between variables. (Note: * is p < 0.05, and ***, p < 0.001.).

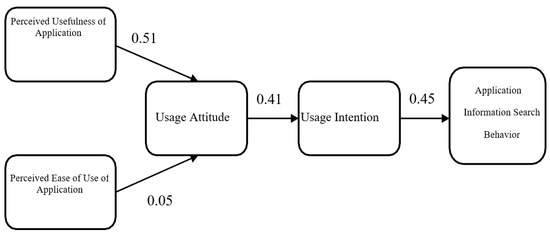

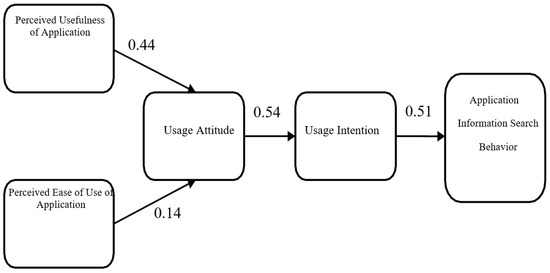

5.3.2. Pre-Travel and During-Travel User Analysis

We used SEM in this study to determine the path coefficients for the use of a tourism APP before and during travel. SEM results are in Figure 3 and Figure 4 below. We see from the analytical results shown in the pathways of the two figures that with regard to the TAM path relationship value for an APP, in addition to the path coefficient of perceived usefulness corresponding to usage attitude being better prior to travel than during travel, for all other path coefficients, usage during travel is superior to usage prior to travel. As such, the new TAM proposed by this study is more suitable for use when investigating tourism APP usage behavior of Foreign Independent Travelers during their travel. We can see from below that the explanatory power of TAM is relatively good with regard to FITs’ use of tourism APPs during travel.

Figure 3.

TAM path relationships for users towards applications prior to travel.

Figure 4.

TAM path relationships for users’ attitude towards APPs during travel.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions and Discussion

- Usage Characteristics for Foreign Independent Travelers and Smartphones

By comparing the results of this study with Xie [33] concerning the personalities of Foreign Independent Travelers (FIT), we see that there are differences between FITs who do and do not use smartphones. With regard to gender, there are more females than males in both groups of respondents. With regard to age, FITs who have not used smartphones are most likely to be between 25–44 years old, while most FITs who have used smartphones are between 18–35. With regard to education, a college education level is the most common in both groups. For employment, students and service industry workers are most common in both groups. The results herein show that with regard to emerging smartphone technologies, the use of smartphones by FIT is the most common among young people and university graduates. Because of the prevalence of service industry workers in Taiwan, the use of smartphones as a search platform by service industry workers is more common than for other industries. FITs most commonly travelled in the Asia-Pacific region for short trips of 4–6-days’ duration under a budget of less than NT$30,000. Furthermore, this study finds among FITs who use smartphones that they most commonly use their smartphones for 6–10 h each day; for use during travel and prior to travel, they utilize their smartphones to search for tourism information. Travelers may prefer to make optimal decisions before embarking on a trip, smartphones provide diverse functions to help travelers make better decisions or adapt to unexpected circumstances during their journey [7,34]. Kang et al. [7] reported that travelers’ characteristics and age were significant variables associated with smartphone use during their trip, and some tourism information categories were searched for more during a trip than before a trip. The five most common items that these travelers think that tourism APPs should improve upon are maps, transportation, points of interest, food and drink, and accommodation. Several studies also indicate a need for improvement and innovation of tourism technology, such as electronic tourist guides and mobile information systems [35,36] Most of these travelers believe that there are not enough types of APPs, that APP content is overly simple, and that APP content should be improved.

- Usage Attitude of APPs

From the results of SEM analysis, we present that the perceived usefulness of APPs positively influences usage attitude. This effect is significant (p < 0.001), and the path coefficient has explanatory power of 48%. Thus, generally speaking, if FITs believe that a smartphone application is helpful, then they exhibit a positive attitude towards operating the APP. On the other hand, we note that the perceived ease of use of APPs positively affects usage attitude. This effect is significant (p = 0.027), although the path coefficient has explanatory power of only 10%. Thus, we can see that FITs typically think that even if a smartphone APP is easy to use, the level to which it positively impacts usage attitude is small. With regard to questionnaire items related to APPs’ perceived ease of use, the item with the lowest score is “I find the smartphone system to be flexible to interact with,” with which respondents only “somewhat agree.” The reason for this may be that there are problems with the user interfaces of smartphone APPs provided by businesses, or the designs of these APPs are flawed. App users and mobile technological innovations shall continue to shape and reshape each other through a process of innovation [34]. This study finds that the usage attitude towards a tourism APP positively affects usage intention. This effect is significant (p < 0.001), and the path coefficient has explanatory power of 50%. Thus, if Foreign Independent Travelers typically have a positive usage attitude towards a tourism APP, then they will generate positive usage intention. They also think that the use of smartphone APPs prior to and during travel is helpful, a good idea, and beneficial. Data show that the usage attitudes of Foreign Independent Travelers towards smartphone tourism APPs are higher for pre-travel use than for during-travel use. The respondents all used tourism APPs prior to and during travel and are willing to continue to use smartphone tourism APPs to conduct tourism information searches prior to and during their next trip.

- Discussion of Usage Intention and Application Information Search Behavior

Behavioral intention is an immediate deciding factor that influences an individual’s action [37], and TAM has received substantial support in explaining users’ acceptance in several domains [6]. Therefore, this study applies TAM to the tourism industry, and according to the results of SEM, we find that the usage intention of an APP positively affects its information search behavior. This effect is significant (p < 0.001), and the explanatory power of the path coefficient is 59%. If FITs typically have a positive usage intention towards a tourism APP, then this will positively influence their information search behavior when conducting tourism information searches. With regard to questionnaire items related to information search behavior, the two items with the highest scores are “I use smartphone APPs to search for travel information frequently” and “There is much travel information in smartphone APPs.” The responses to these items are between “somewhat agree” and “agree.” However, the item with the lowest score is “Overall, using smartphone APPs to search for travel information is more useful than using a computer”; respondents typically “somewhat agreed” with this statement. Thus, we can see that Foreign Independent Travelers think that using smartphone APPs is less than ideal compared to using the internet. The reason for this may be evident when we compare it with the following questionnaire item: “Which problems did you encounter when using smartphone APPs to search for tourism information during your most recent journey?” Most respondents said that there were not enough kinds of tourism APPs, and that APP content was too simple and could not be understood in depth; other respondents found it difficult to access Wi-Fi during their travels.

This study uses SEM to show that each path relationship and hypothesis is supported, while only the relationship effect in H2 is relatively weak. This study conducts regression analysis, and its results are in Table 6. After using regression analysis to conduct hypothesis testing, we find that H1, H2, H3, and H4 are all supported; these results are the same as those from SEM data analysis. However, the significance levels indicated by regression analysis are higher than those from SEM, with p < 0.001 indicating extreme statistical significance. With regard to H2, Foreign Independent Travelers’ perceived ease of use of smartphone APPs positively affects usage attitude, and the adjusted R2 = 0.132. This is somewhat lower than other hypothesis testing results and is similar to the SEM data analysis result. When using regression analysis to conduct testing, in addition to using simple linear regression, we also employ complex regression analysis to test whether variables such as perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, usage attitude, and usage intention influence information search behavior. For this analysis, the highest adjusted R2 = 0.368, confirming that each variable correlates with information search behavior.

Table 6.

Regressions analysis.

6.2. Practical Implications

According to the above findings, this study argues that if FITs have positive perceptions, attitudes, and intentions towards smartphone tourism APPs, then they will be more likely to use such APPs to conduct tourism information searches. However, the content of existing tourism APPs can still be greatly improved. In addition to adding new types of tourism APPs and increasing the content of existing tourism APPs, more offline-capable tourism APPs should be developed in order to resolve FITs’ problems related to their deficiencies while abroad. Smartphones have rapidly grown to be utilized as a travel tool and are frequently used in tourism information research and travel planning [38,39]. This study provides some practical implications. Both prior to and during their travels, the results of this study show that FITs use smartphones as a tool for conducting tourism information searches. In the future, this phenomenon of using smartphones to search for tourism information will only increase. Taiwan’s Ministry of Transportation and Communications’ (MOTC) Tourism Bureau [3] points out that Taiwanese foreign trips received 32% growth in outbound foreign tourism over four years. With regard to Taiwanese people’s chosen method of tourism, 65% travel independently. However, most existing Taiwanese tourism APPs are only suitable for domestic travel. As such, we hope that technology businesses can increase the development of more Chinese language tourism APPs for international travel usage. Furthermore, most FITs believe that the variety of tourism APP types is insufficient, and that APPs’ content is overly simple and impossible to understand in-depth. On the other hand, FITs travel alone or accompanied by a small number of people.

The goal of FITs is to explore the things they want to see and that create unique travelling experience. According to the World Tourism Organization [40], sustainable tourism is tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social, and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, and industry, the environment, and host communities; moreover, sustainable tourism should maintain a high level of tourist satisfaction and ensure a meaningful experience for the tourists. By using mobile technologies and APPs, travelers want to save time, be more efficient and effective [41,42]. FITs want more control of their travel experiences, with greater emphasis on making their own decisions during trips. Thus, in order to ensure a meaningful traveling experience, we suggest that technology businesses can strongly enhance tourism related APPs and can also supplement content related to APP items that travelers currently find insufficient: transportation, maps, points of interest, food and drink, accommodation, and weather. This study confirmed that the TAM model is still valid and can be applied in the area of tourism. Moreover, the findings enhance understanding of how smartphones can impact FIT travel experiences in tourist destinations.

6.3. Research Limitations and Recommendations

Even though this study has provided some insights, it has several limitations. This study only conducted a survey of Taiwanese FITs; the sampling techniques may make results vulnerable. As such, the result may not be generalized. Second, due to the limited internet/Wi-Fi service overseas, Taiwanese FITs perhaps might have been reluctant to use their smartphones during their trip and thus limited experience was achieved. Additionally, this study only conducted research on smartphones. Thus, it is not possible to apply the research results to other technology products such as tablet computers, notebook computers, or smart watches. According to Distimo’s Review [43], in Apple’s App Store, the number one paid application is a tourism-type navigation system; this application is almost twice as expensive as the number two application, a commercial application. Future research should explore potential issues related to the cost of tourism applications. While most smartphone tourism APPs can currently be used by Taiwanese people for domestic tourism, there are few Chinese language tourism APPs for overseas use. Thus, those APPs are not commonly used by Taiwanese FITs which increases the difficulty of this study.

Author Contributions

S.-W.L. and S.-Y.L. conceived of the presented idea. S.-Y.L. encourage S.-W.L. to investigate the aspect and supervised the findings of this work. P.-J.J. Juan assisted with data analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brown, B.; Chalmers, M. Tourism and mobile technology. In Proceedings of the Eighth European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Helsinki, Finland, 14–18 September 2003. [Google Scholar]

- eMarketer. Mobile Taiwan: A look at a Highly Mobile Market. Available online: https://goo.gl/knua2v (accessed on 16 December 2016).

- Ministry of Transportation and Communication, Tourism Bureau. Survey on Taiwanese Tourism Conditions in 2016. 2017. Available online: http://admin.taiwan.net.tw/statistics/year.aspx?no=134 (accessed on 20 December 2017).

- Institute for Information Industry. Survey on Smart Home and Mobile Applications. 2012. Available online: http://www.find.org.tw/find/home.aspx (accessed on 27 November 2016).

- Aldebert, B.; Dang, R.J.; Longhi, C. Innovation in the tourism industry: The case of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1204–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C. A current travel model: Smart tour on mobile guide application services. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2332–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Jodice, L.W.; Norman, W.C. How do tourist search for tourism information via smartphone before and during their trip? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.J. Continued Participation and Perceived Risk by Foreign International Tourists. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Leisure and Exercise Studies, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin County, Taiwan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins, R.A. The costs and benefits of hedonism: Some consequences of taking casual leisure seriously. Leis. Stud. 2001, 20, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazazo, I.K.; Alananzeh, O.A.; Taani, A.A.A. Marketing the therapeutic tourist sites in Jordan using geographic information system. Marketing 2016, 8, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, R.; Mostofa, M.G.; Khondker, T.W. Mobile technology uses towards marketing of tourist destinations: An analysis from therapeutic point of view. J. Mob. Comput. Appl. 2019, 6, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.P.; Yeh, Y.H. Effect of use contexts on the continuous use of mobile services: The case of mobile games. Pers. Ubiquit. Comput. 2010, 15, 87–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.G.; Lee, J.H.; Law, R. An empirical examination of the acceptance behavior of hotel front office systems: An extended technology acceptance model. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosan, C. Theoretical and empirical considerations of guests’ perceptions of biometric systems in hotels: Extending the technology acceptance model. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 36, 52–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.B.P.; Wan, G. Including subjective norm and technology trust in the technology acceptance model: A case of E-ticketing in China. Adv. Inform. Syst. 2010, 41, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Lehto, X.Y.; Park, J. Travelers’ intent to use mobile technologies as a function of effort and performance expectancy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudon, D.L.; Della, B.; Albert, J. Consumer Behavior: Implications for Marketing Strategy, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M.R. Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having and Being; Prentice Hall Trade: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Q. A discussion of literature related to internet use and information search behavior. Univ. Lib. J. 2010, 5, 144–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fodness, D.; Murray, B. Tourist information search. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transportation and Communication, Tourism Bureau. Survey on Taiwanese Tourism Conditions in 2011. 2012. Available online: http://admin.taiwan.net.tw/statistics/year.aspx?no=134 (accessed on 25 December 2017).

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepper, M.R. Microcomputers in education: Motivational and social issues. Am. Psychol. 1985, 40, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.; Karsh, B.T. The Technology Acceptance Model: Its past and its future in health care. J. Biomed. Inform. 2010, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, K. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control, 9th ed.; Prentice Hall International: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, S.P. Organizational Behavior, Blackboard; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein, T.A.; Black, J.S. Attitudinal specificity and the prediction of behavior in a field setting. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1976, 33, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, P.H.; Daniel, L.S.; Nancy, M.R. Consumer search: An extended framework. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hella, L.; Krogstie, J. Personalisation by semantic web technology in food shopping. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Sogndal, Norway, 25–27 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.L. Relationship between Personality, Health-Oriented Lifestyle and Educational Tourism for Foreign Independent Tourists. Master’s Thesis, Department of Tourism Management, Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Smartphone use in everyday life and travel. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenteris, M.; Gavalas, D.; Economou, D. An Innovative mobile electronic tourist guide application. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2009, 13, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Schuckert, M.; Law, R.; Masiero, L. The relevance of mobile tourism and information technology: An analysis of recent trends and future research directions. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 732–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, W.K. The relationship between smartphone usage, tourist experience and trip satisfaction in the context of a nature-based destination. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Hatamifar, P.; Ghahramani, L. How smartphones enhance local tourism experiences? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP & UNWTO. Making Tourism More Sustainable—A guide for Policy Makers. 2005. Available online: http://www.unep.fr/shared/publications/pdf/DTIx0592xPA-TourismPolicyEN.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Dorcic, J.; Komsic, J.; Markovic, S. Mobile technologies and applications towards smart tourism—State of the art. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barder, A.; Baldauf, M.; Leinert, S.; Fleck, M.; Liebrich, A. Mobile tourism services and technology acceptance in a mature domestic tourism market: The case of Switzerland. In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2012, Helsingborg, Sweden, 25–27 January 2012; pp. 296–307. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, S. Distimo’s 2012 Year in Review. 2013. Available online: http://www.distimo.com/blog/2012_12_publication-2012-year-in-review/ (accessed on 27 January 2013).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).