Toward Sustainable ICT-Supported Neighborhood Development—A Maturity Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Community Development

2.2. Digital Tools for Community Collaboration

- communication (e.g., audio/video conference systems, file transfer, email, instant messaging),

- cooperation (e.g., weblog, wiki) and

- coordination (e.g., social tagging, voting tool, application sharing tool, bulletin board) [18].

2.3. Implementation and Evaluation of Technology for Neighborhood Development

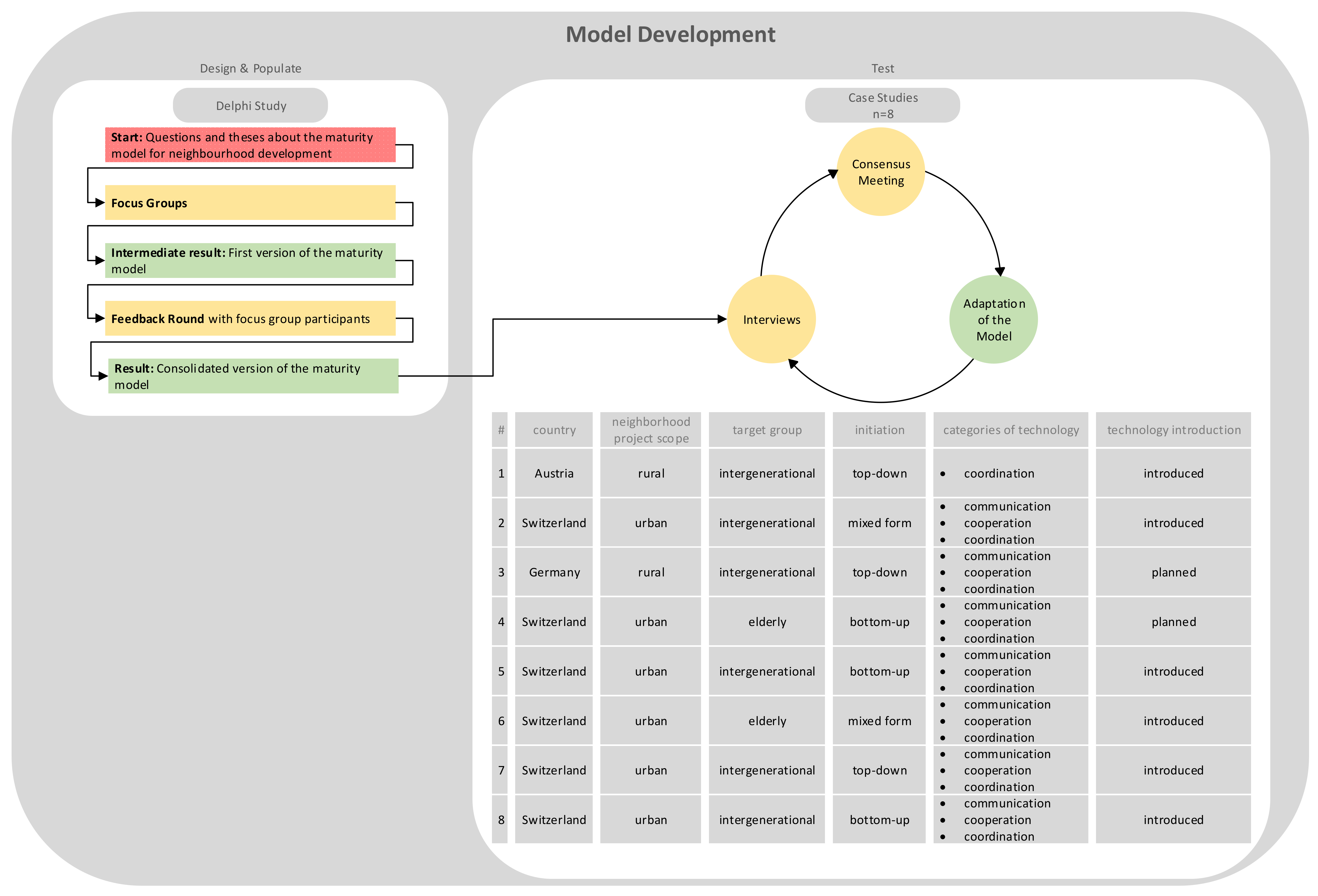

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design/Populate Phase

3.2. Test Phase–Validation and Adaptation in Case Studies

4. Results

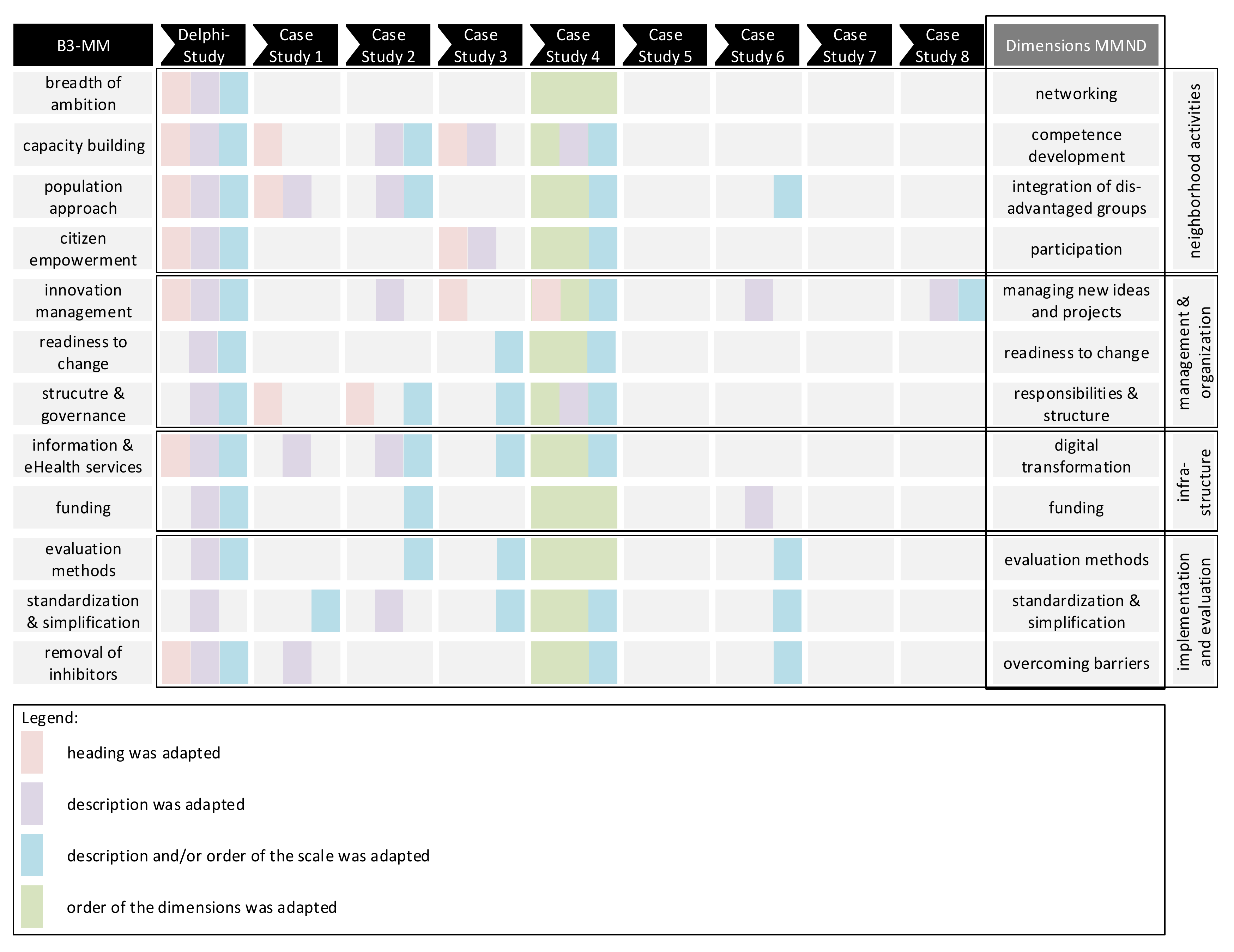

4.1. Transferability of the B3-MM to the Neighborhood Context

4.2. Adaptations to the Model

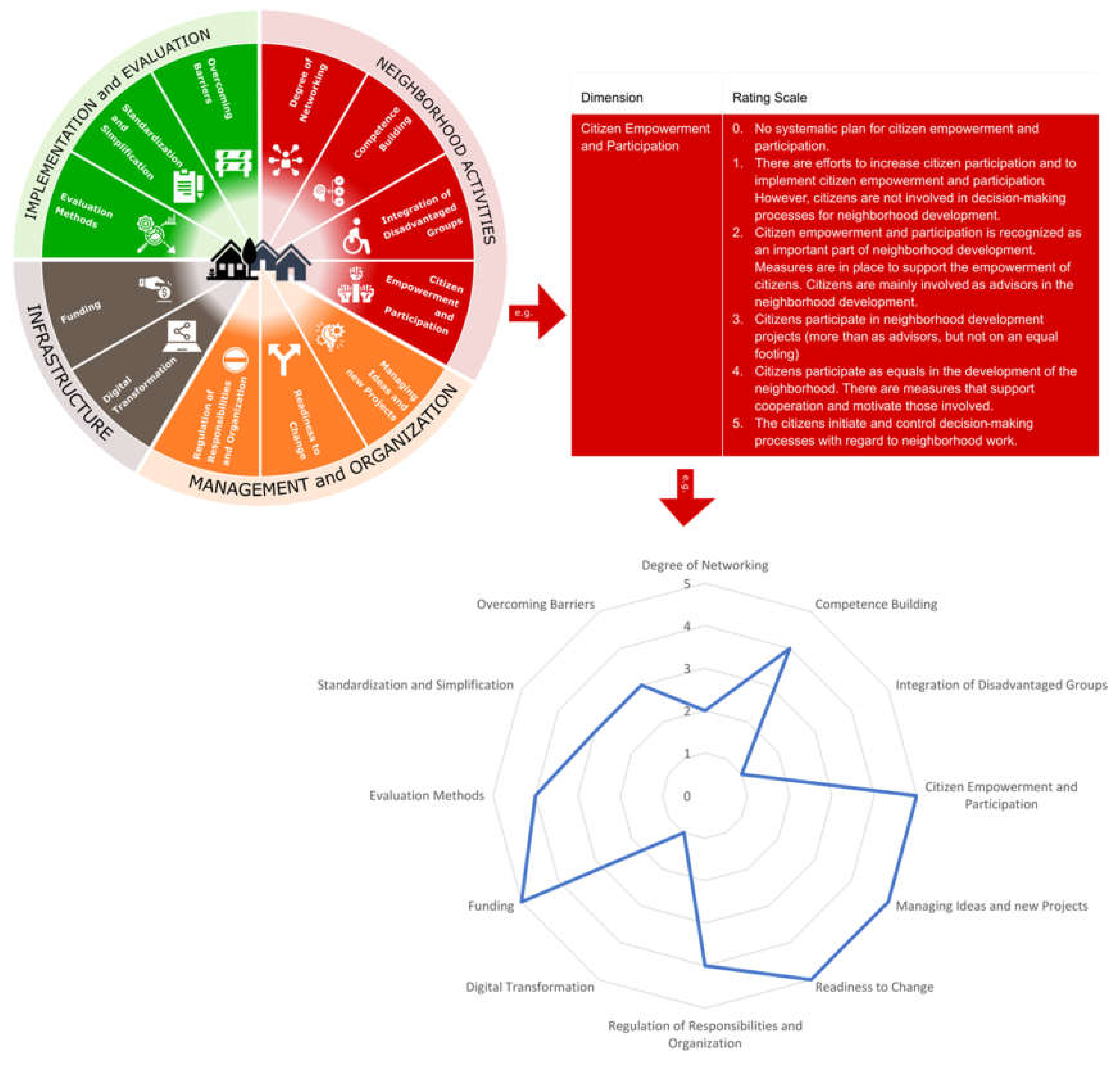

4.3. Dimensions for ICT-supported Neighborhood Development

4.3.1. Neighborhood Activities

- Degree of Networking (Degree of Integration) in the Neighborhood:A community is comprised of a wide variety of actors from different sectors including civil society, health and social services. As cooperation and exchange between actors become more formalized and more actors from different sectors participate, a broader network is formed. A long-term goal of neighborhood development is promoting systematic cooperation and exchange among all actors in a neighborhood, with the ultimate goal of achieving comprehensive community-based cooperation among the population.

- Competence Development to Foster (Volunteers’) Capacity Building:In the context of neighborhood development, volunteers tend to play a crucial role. The acquisition, improvement, and maintenance of relevant skills is an important but complex task, largely due to the heterogeneity of this group. Volunteers often lack specific knowledge, including knowledge related to administrative necessities. The development of competence among citizens will increase the capacity for neighborhood development.

- Community Orientation and Integration of Disadvantaged Groups:The aim of community orientation is to improve the living conditions of all actors at local and regional levels through, with, and for local people. Often, disadvantaged people can only participate in social life to a limited extent and do not fully benefit from existing support systems. Neighborhood development projects can contribute to improving the quality of life for people in vulnerable groups and promoting their inclusion in the community. The fostering of participation and inclusion of these groups will then, as a by-product, maintain their individual health.

- Citizen Empowerment and Participation in Neighborhood Work:Neighborhood work is about the resources in the neighborhood, the strengthening of self-management and processes of self-organization, and networking and cooperation among local institutions and actors. This dimension is concerned with enabling participation of citizens as co-designers of change processes. To address this dimension, the population must be provided with easy-to-use tools that promote their involvement in neighborhood development, such as technical solutions that allow people to express their opinions.

4.3.2. Management and Organization

- Managing Ideas and new Projects:Many of the best ideas are likely to come from committed neighborhood residents or professionals who understand where improvements can be made to existing processes. These innovations need to be recognized, assessed and, where possible, scaled up to provide benefits across the neighborhood. The focus of this dimension is not on the technological or material but on social innovations (e.g., using ICT for neighborhood development).

- Readiness to Change to Community-based Development:Change in existing systems is often accompanied by the creation of new roles, processes and working practices. Such change requires a broad-based motivation for change and a strategy and vision of how neighborhood cooperation should be shaped in the future.

- Regulation of Responsibilities and Organizational Structure:The structuring of neighborhood work and higher-level governance is not a guarantee of success. In the context of neighborhood development, control at the regional or local level is preferable. Structure is seen as a service provided by the municipality to the citizens. This service can be used on a voluntary basis for project development but is not mandatory to use.

4.3.3. Infrastructure

- Digital Transformation:A lively neighborhood relies on communication, exchange and community. Transparency and communication between citizens and local professional actors and institutions are an important basis for effective neighborhood work. In contrast to integrated care, digital information and communication services are used to support community work and interaction in a neighborhood. These services should support the efficient cooperation of community actors and enable citizens and multipliers to interact and participate in the neighborhood development. Digital services are ideally based on existing offerings and structures. Digital interaction possibilities should also be based on and extend existing networks.

- Funding:Successful and sustainable community development requires an initial investment at both organizational and technical levels, as well as continued financial support until new structures and services are fully operational. Ensuring the financing of initial and running costs is therefore an essential measure.

4.3.4. Implementation and Evaluation

- Evaluation Methods:The evaluation of interventions for digitally supported neighborhood development is often a prerequisite for funding and official recognition. Evaluation is also a tool for standardizing procedures and thus facilitates the exchange and transfer of best practices.

- Standardization and Simplification:Standardization of procedures and implementation strategies for ICT can simplify collaboration among all involved actors. Furthermore, the exchange of guidelines and best practices between projects and neighborhoods could be desirable.

- Overcoming Barriers:Good technologies alone do not guarantee successful neighborhood development. User-friendly and self-explanatory technology may be subject to other barriers, including a lack of political support or insufficient marketing, which may prevent the spread of the technology. The “removal of inhibitors” may not always be possible in neighborhood development; therefore, this dimension must focus on how to manage these barriers.

5. Discussion

5.1. Application of the Model

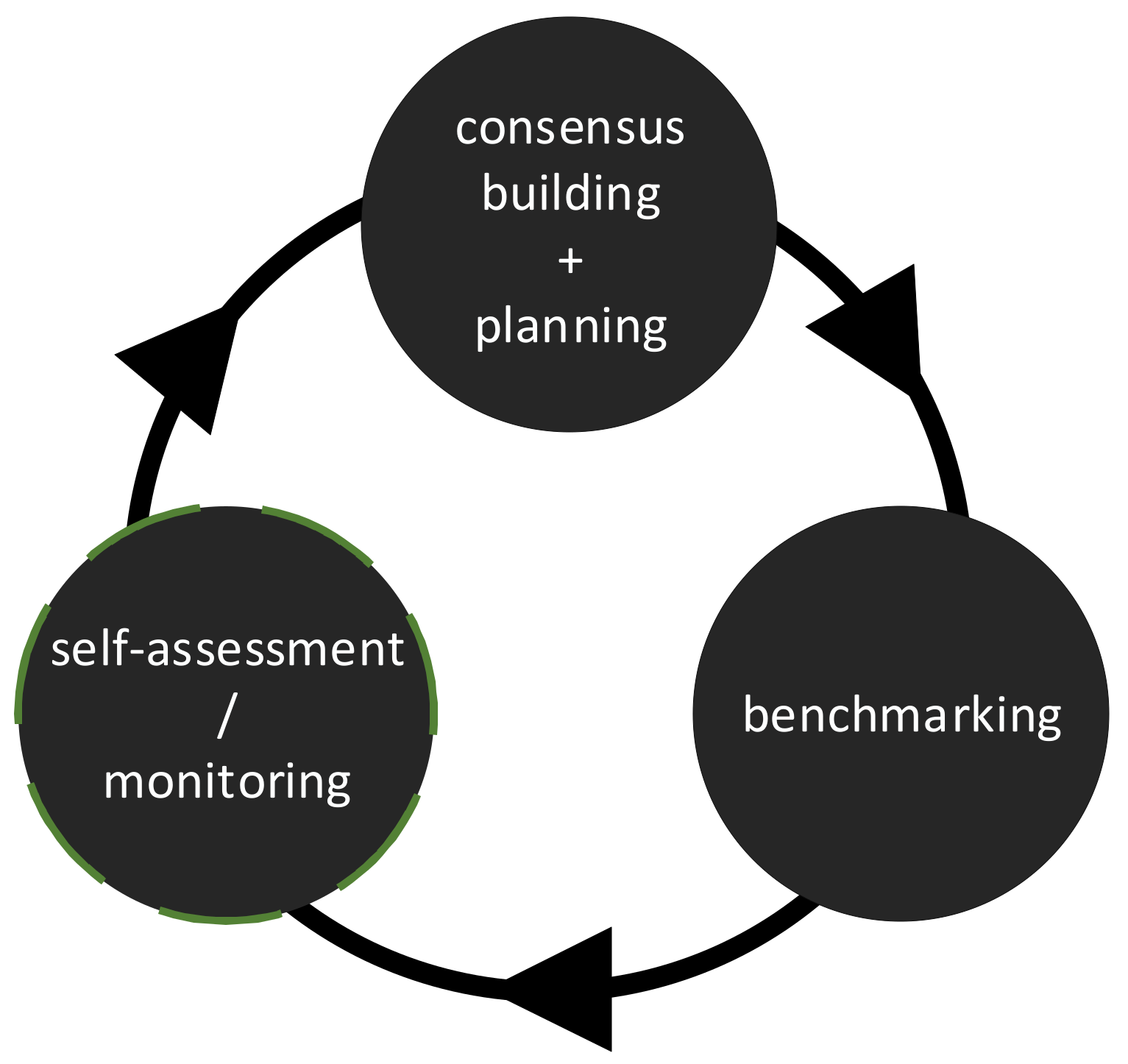

- Self-AssessmentThe MMND can be used as a self-assessment tool with which a neighborhood developer or a team of neighborhood developers can evaluate the current state of a project. The results of the self-assessment could also be communicated to existing or potential funders if required or desired.

- Tool for consensus buildingThe MMND could be the basis for a consensus process between diverging neighborhood stakeholders. In this case, each stakeholder or stakeholder group would conduct a self-assessment prior to a consensus-building workshop. In the workshop, the self-assessment results would be compared and discussed to reach consensus about what strategy to adopt and how to proceed in the future.

- Planning ToolThe model can also serve as a basis for comprehensive project planning. In this case, the tool could be used for orientation at the beginning of a project. A planning workshop should consist of three steps: First, the status quo of the neighborhood should be assessed for each dimension. Second, a maturity target for each dimension should be determined. Finally, the necessary steps to achieve the target must be defined.

- Benchmarking/Exchange of Best PracticesOn the basis of prior self-assessments, it could be desirable to compare and exchange experiences between neighborhoods. The eight case studies demonstrate that accompanying materials and procedures would need to be standardized and made easily accessible to achieve this exchange of ideas.

- MonitoringThe maturity model could be used to monitor the achievement of milestones and project progress at regular intervals. The majority of practitioners felt that, if the model was used repeatedly over an extended period of time, progress would be made visible.

5.2. Target Users of the Model

5.3. Defining the Object of Investigation and Maturity Level

5.4. An Excurus: The Impact of the Coronavirus

5.5. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bianchi, S.M. A Demographic Perspective on Family Change. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2014, 6, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoormann, T.; Kutzner, K. Towards Understanding Social Sustainability: An Information Systems Research-Perspective. In Fourty-First International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2020; AIS: Hyderabad, India, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Klie, T. On the way to a Caring Community? In Compassionate Communities: Case Studies from Britain and Europe; Wegleitner, K., Heimerl, K., Kellehear, A., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016; pp. 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar, H.; Bühler, E. Planning, design and use of the public space Wahlenpark (Zurich, Switzerland): Functional, visual and semiotic openness. Geogr. Helv. 2009, 64, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, H. Rezension zu «Gelebter, erfahrener und erinnerter Raum» von Hasse, Jürgen und Robert Josef Kozljanič (Hrsg.). Die Erde 2012, 143, 378–380. [Google Scholar]

- Buühler, E. Sozial Nachhaltige Parkanlagen: Forschungsbericht des Nationalen Forschungsprogramms NFP 54 “Nachhaltige Siedlungs-und Infrastrukturentwicklung”; vdf, Hochschulverl an der ETH: Zürich, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (Ed.) World Report on Ageing and Health; WHO Press: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, M.; Hayes, R.; Moore, D.; Petticrew, M.; Clow, A.; Schmidt, E.; Draper, A.; Lock, K.; Lynch, R.; Renton, A. Evaluation of community level interventions to address social and structural determinants of health: A cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandersman, A.; Florin, P. Community Interventions and Effective Prevention. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooten, L.; Borgermans, L.; Jm Vrijhoef, H. An Instrument to Measure Maturity of Integrated Care: A First Validation Study. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, G.P.; Haines, A. Asset Building & Community Development; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ledwith, M. Community Development: A Critical Approach; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heite, E.; Rüßler, H.; Stiel, J. Alter(n) und partizipative Quartiersentwicklung: Stolpersteine und Perspektiven für soziale Nachhaltigkeit. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 48, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisch, M.; Boos-Krüger, A.; Ritter, M.; Schönberger, C. (Eds.) „Irgendwann Brauch’ich dann auch Hilfe…!“–Selbstorganisation, Engagement und Mitverantwortung Älterer Menschen in Ländlichen Räumen; Budrich Verlag: Opladen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Drilling, M. Verstetigung in der nachhaltigen Quartiersentwicklung: Eine Analyse aus Sicht der Urban Regime Theory. Geogr. Helv. 2009, 64, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Böhme, C.; Franke, T. Soziale Stadt und ältere Menschen. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 43, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolfschoten, G.; Briggs, R.O.; De Vreede, G.-J.; Jacobs, P.H.M.; Appelman, J.H. A conceptual foundation of the thinkLet concept for Collaboration Engineering. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimeister, J.M. Collaboration Engineering: IT-Gestützte Zusammenarbeitsprozesse Systematisch Entwickeln und Durchführen; Springer Gabler: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Vreede, G.J.; Davison, R.M.; Briggs, R.O. How a silver bullet may lose its shine: Learning from failures with group support systems. Commun. ACM 2003, 46, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, N.; Villaseñor, N.; Yagüe, M. Sustainable Co-Creation Behavior in a Virtual Community: Antecedents and Moderating Effect of Participant’s Perception of Own Expertise. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeppelbuss, J.; Niehaves, B.; Simons, A.; Becker, J.; Pöppelbuß, J. Maturity Models in Information Systems Research: Literature Search and Analysis. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2011, 29, 505–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, A.K.; Garousi, V.; Turetken, O.; Söylemez, M.; Garossi, S. Maturity assessment and maturity models in healthcare: A multivocal literature review. Digit. Health 2020, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler, R. The maturity of maturity model research: A systematic mapping study. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2012, 54, 1317–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.V.; Rocha, Á; Van de Wetering, R.; Abreu, A. A Maturity model for hospital information systems. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkman, M.M.N. The development model for integrated care: A validated tool for evaluation and development. J. Integr. Care 2016, 24, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calciolari, S.; Ilinca, S. Unraveling care integration: Assessing its dimensions and antecedents in the Italian Health System. Health Policy 2016, 120, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, C.V.D.; Meterko, M.; Lowcock, S.; Donaldson-Parlier, R.; Blakely, M.; Davies, M.; Petzel, R.A. Monitoring the progress of system integration. Qual. Manag. Healthc. 2002, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, G.; Roberts, J.; Gafni, A.; Byrne, C.; Kertyzia, J.; Loney, P. Conceptualizing and validating the human services integration measure. Int. J. Integr. Care 2004, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. A Maturity Model for Adoption of Integrated Care within Regional Healthcare Systems (B3 Action Group). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/repository/maturity-model-adoption-integrated-care-within-regional-healthcare-systems-b3-action_en (accessed on 18 October 2019).

- De Bruin, T.; Freeze, R.; Kulkarni, U.; Rosemann, M. Understanding the Main Phases of Developing a Maturity Assessment Model. In Proceedings of the 16th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, ACIS 2005 Proceedings, Sydney, Australia, 30 November–2 December 22005; p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Renyi, M.; Rombach, E.; Teuteberg, F.; Kunze, C. Towards Understanding the Use of Information Systems in Caring Communities. In Proceedings of the 25th American Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2019 Proceedings, Cancun, Mexico, 15–17 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, E.L.; Maciel, R.S.P. Maturity Models Architecture: A large systematic mapping. iSys Rev. Bras. Sist. Inf. 2020, 13, 110–140. [Google Scholar]

- Uijen, A.A.; Heinst, C.W.; Schellevis, F.G.; Van den Bosch, W.J.H.M.; Van de Laar, F.A.; Terwee, C.B.; Schers, H.J. Measurement Properties of Questionnaires Measuring Continuity of Care: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheelan, S.A. Group Size, Group Development, and Group Productivity. Small Group Res. 2009, 40, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturriza, M.; Hernantes, J.; Labaka, L. Coming to Action: Operationalizing City Resilience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.M.; Deshpande, V.A. Application Of Plan-Do-Check-Act Cycle For Quality And Productivity Improvement-A Review. IJRASET 2017, 5, 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Grooten, L.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M.; Alhambra-Borrás, T.; Whitehouse, D.; Devroey, D. The transfer of knowledge on integrated care among five European regions: A qualitative multi-method study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Internationale Bodensee-Hochschule IBH. Technik im Quartier. Available online: https://www.bodenseehochschule.org/ibh-labs/ibh-lab-aal/technik-im-quartier/ (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Coronavirus: Antworten auf Häufige Pressefragen|nebenan.de. Available online: https://presse.nebenan.de/pm/coronavirus-antworten-auf-haufige-pressefragen (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Gemeinde-Kommunikation–Enormer Digitaler Nachholbedarf|C-Factor. Available online: https://www.cfactor.ch/blog/blog-gemeinde-kommunikation/ (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Eisenmann, H.J. Digitale Dürrheimer Bürgerplattform soll Ende 2020 an den Start Gehen Südwest Presse Die Neckarquelle. 2020. Available online: https://www.nq-online.de/lokales/bad-drrheim/digitale-duerrheimer-buergerplattform-soll-ende-2020-an-den-start-gehen_896_111925868-16-.html (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Zeiter Platz für Diemelstadt APP bei “Hessen Smart Gemacht”. Available online: https://www.diemelstadt.de/aktuelles/2020/zeiter-platz-fuer-diemelstadt-app/ (accessed on 9 October 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Renyi, M.; Hegedüs, A.; Maier, E.; Teuteberg, F.; Kunze, C. Toward Sustainable ICT-Supported Neighborhood Development—A Maturity Model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229319

Renyi M, Hegedüs A, Maier E, Teuteberg F, Kunze C. Toward Sustainable ICT-Supported Neighborhood Development—A Maturity Model. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229319

Chicago/Turabian StyleRenyi, Madeleine, Anna Hegedüs, Edith Maier, Frank Teuteberg, and Christophe Kunze. 2020. "Toward Sustainable ICT-Supported Neighborhood Development—A Maturity Model" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229319

APA StyleRenyi, M., Hegedüs, A., Maier, E., Teuteberg, F., & Kunze, C. (2020). Toward Sustainable ICT-Supported Neighborhood Development—A Maturity Model. Sustainability, 12(22), 9319. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229319