Abstract

Entrepreneurship and more, particularly ecopreneurship, are essential to drive the sustainable transitions needed in food supply chains. Existing pedagogic frameworks should address these academic disciplines and they should be embedded in the educational curricula. Even when ideas are formed that can drive sustainable change, the process from ideation to commercialization can be difficult: the so-called “valley of death.” This aim of this conceptual paper is to consider pedagogic and program design and the mechanisms required to enaction of a body of practice around entrepreneurship and, more specifically, ecopreneurship, within academic curricula and associated business incubators. This makes this paper of particular interest for academia, policy makers and industry support sectors alike. An existing university that has both a student enterprise and ecopreneurship program and an established agri-technology business incubator and accelerator is used as a case study to provide insight into how progress from ideation to commercialization can be more readily supported in a university setting. From a pedagogical perspective, it is incumbent to develop new conceptual, methodological and theoretically underpinned spiral pedagogies to teach and support future generations of learners at agricultural and land-based colleges and universities as to how to exploit and take advantage of entrepreneurial and ecopreneurial business opportunities. Productization, too, needs to be embedded into the ecopreneurial pedagogy and also consideration of how businesses and their associated ecopreneurs navigate from ideation to successful product/service commercialization.

1. Introduction

Technological improvements in the agri-food supply chain have driven efficiency, reductions in emissions and more efficient use of resources including water and energy, but those incremental benefits have mainly been offset by increasing production and consumption volumes to meet a rising global human population [1]. Concern over depletion of natural resources [2] has driven governments, non-governmental organizations, private organizations, and by inference their supply base, rural and urban communities and individuals who live within them to consider how the way food is produced, purchased and consumed is transitioned in order to deliver sustainable development goals [3]. Sustainable development has been described as the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [4]. Sustainable transition, the “radical transformation towards a sustainable society as a response to a number of persistent problems confronting contemporary modern societies” [5] (p.1), is co-defined and co-created by a broad range of actors [6]. Sustainable transitions shift an existing regime from one particular socio-technical configuration towards another [7] with a new normative, cultural nexus, framed by the narrative of the empowered, informed individual or organization becoming a change agent in a complex, uncertain world. Ecopreneurship is not a new term and two decades ago was defined as “social activists, who aspire to restructure the corporate culture and social relations of their business sector though proactive, ecologically oriented business strategies” [8] (p. 88). The term is also said to describe green entrepreneurship or green business [9], an environmental orientation [10], entrepreneurship through an environmental lens [11] and as a construct with the potential to “lead disruptive and much needed transformations in society” [12]. Indeed, it has been argued that ecopreneurship focuses on personal skills and innovation rather than wider business management, i.e., it can be personality driven [11] and can be a form of intrapreneurship within an existing business [13]. Transitioning the so-called “valley of death” from invention to innovation for any entrepreneur can be compromised by lack of financial resources [14,15] and the knowledge gap between the science and the development of commercial products in the “ideation phase.” [16] The valley of death has also been articulated as being a transition from a science and technology (normative) domain to a commercial (cultural) domain and this requires clear articulation of the transitioning narrative, the skills needed to commercialize, and the project goal, i.e., what success looks like [17]. The practices and intrinsic features of the business incubators also play a role [18]—e.g., space, shared support services, business services, advice, coaching and mentoring, and network infrastructure—both internal and external to the incubator and graduation processes [19]. Therefore, when developing learning environments around enterprise, entrepreneurship, and ecopreneurship specifically, for farmers, technology specialists and students of agriculture and agri-business, research informed pedagogy sits at the heart of driving successful commercial outcomes for individuals and the businesses they create or work within.

In this review, we examine several selected strands of protean literature and how they frame pedagogic practice and also the innovation journey from novel idea through to full product or service commercialization [20] and consider the role of the university in this journey. At present, these strands of research discipline sit separately within the sub-strands of rural entrepreneurship, ecopreneurship, strategy and innovation within the traditional business school curriculum, and are often absent in the agricultural and agri-business related pedagogy and, where included, are not taught as a discrete corpus of knowledge. A case study approach is used to explore these research areas of interest and provide insight into how entrepreneurial and ecopreneurial activity can be supported in a university setting. This aim of this conceptual paper is to consider pedagogic and program design and the mechanisms required to enaction of a body of practice around entrepreneurship and, more specifically, ecopreneurship within academic curricula and associated business incubators. The key question is how can entrepreneurial and ecopreneurial disciplines be incorporated into a learning program with specific emphasis on driving sustainable transition?

2. Literature Review

What are the contemporary literatures of interest? This research synthesizes the disparate literature on entrepreneurship and farming and food production to consider: (1) the emerging agricultural entrepreneurship literature; (2) rural entrepreneurship; (3) entrepreneurial legacy; (4) entrepreneurial bridging; (5) ecopreneurship and environmental sustainability; and (6) the entrepreneurship-dyslexia-farming nexus. Each is now considered in turn.

The emerging agricultural entrepreneurship literature: Agricultural entrepreneurship sits within the sub-literature of rural entrepreneurship but, paradoxically, is distinct from it. There is growing recognition of the importance of farm-based, or agricultural, entrepreneurship that is reflected in an expanding academic literature in entrepreneurship and farming journals as well as in textbooks [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. There is also a sub-literature on agri-technology that sits within the wider theme of agricultural entrepreneurship [29,30,31]. Smart agripreneurial technologies are innovations designed to improve farm output and yields via improved data, collection tracking and usage, better efficiency and in so doing can reduce production costs and increase food availability and affordability [24,32]. Whilst the term agri-technology or “agri-tech” is used widely as a colloquial term in education and industry, there is a lack of definition of this term in academic or grey literature. It is therefore an umbrella term used to describe emergent technological applications, innovation and entrepreneurial activity that benefits (increases yield, efficiency or profitability) food production and land-based industries as a whole and, more specifically, agriculture, aquaculture (farmed and wild), forestry horticulture, and maintenance of landscapes and cultural heritage. This paper is one of the first to seek to give a clear definition of this term.

The entrepreneurial farmer: The growing appreciation of the role of entrepreneurship in agriculture and food production results from the notion of the farmer as “entrepreneur” [33,34]. This strand of the literature has rapidly expanded in recent years and is now under-pinned by a sound, theoretically based body of work. A major theme of this literature is that, traditionally, farmers were regarded as being conservative in nature, anti-entrepreneurial and risk-adverse in their practices [33]. As a result, the label of “being an entrepreneur” and its theoretical foundation does not resonate with many farmers when they consider their self-identity. However, notwithstanding this, paradoxically, farmers are entrepreneurial in their nature and outlook and improvise and innovate naturally as a result of the uncertain environment in which they operate. Historically, education as an activity, especially higher education, was not considered a priority by the farming community. Indeed, farming is very much an occupation that one “learns by doing” [35] through a process of “situated learning” [36]. It could be argued that, historically, prospective farmers were often socialized into their practices as “farm reared children” educated on farms by generations of farmers and farming communities [37]. This surge in the literature on the entrepreneurial farmer is testament to the fact that, increasingly, farmers are becoming more entrepreneurial in their approach [38], especially as farmers increasingly have no option but to become more entrepreneurial in both their core and diversified business interests [33]. Nevertheless, the expanding literature on farm-based entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurial farmer, it can be argued, has yet to seriously impact the curriculum of the majority of agricultural and land-based colleges and universities.

Rural entrepreneurship is a strong theme in the literature and increasingly so in recent years. The literature has developed across a global landscape and considered all business activity in rural locations [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Entrepreneurial diversification and pluriactivity is an area of interest within the rural entrepreneurship literature [45,46,47,48,49]. The themes of entrepreneurial pluriactivity and income accumulation [50], which are closely related to the topic of entrepreneurial diversification, are an important element in the farming sector and, accordingly, there is a healthy literature [22,40,50,51,52]. The topic of pluriactivity differs from that of diversification because it need not be related to the original farm business, but to other knowledge or skills available to the farmer and the extended household or just even property speculation. There are three types of entrepreneurs: the pluriactive farmer, the resource exploiting entrepreneur and the portfolio entrepreneur [51]. These entrepreneurial types possess different motivation and objectives and, as a result, their activities can lead to different business models. This diversity of business model is nothing new as, traditionally, many farm households have relied on income from multiple sources to prosper or perhaps even just survive [52]. Pluriactivity is often associated with survival in resource-constrained environments [48]. This can be a deliberate strategy, or one forced on farmers and the farm household by personal circumstances and/or by external conditions. The sources of income can be on-farm and/or off-farm.

Issues of family and kinship are important in relation to both diversification and pluriactivity in a farming context because household strategy influences the development of new businesses, the ways in which household characteristics and dynamics influence business growth strategy decisions and how business portfolios are managed and developed by the wider entrepreneurial household [53]. Three analytical themes emerge: the tightly interwoven connections between the business and the household, the use of family and kinship relations as a business resource base and how households mitigate risk and uncertainty through self-imposed growth controls. This serves to illustrate that whilst entrepreneurial growth may be an outcome of personal ambition and business strategy, the active role played by the entrepreneurial household and the household strategy in determining business growth activities is of vital importance [53]. From a brief perusal of the literature, it is apparent that the subject of entrepreneurial pluriactivity is of importance both theoretically and practically to those in the farming and land-based industries albeit that pluriactivity as a concept may not be deeply embedded in the curriculum at agricultural and land-based universities and colleges.

Diversification can occur either through deepening the agricultural business by (1) improving product quality or moving activities further down the supply chain e.g., processing or retailing; (2) broadening into other rural based enterprises e.g., tourism or business rental; or (3) mobilizing business resources through regrounding e.g., deintensifying agricultural activities, undertaking activities that are rewarded by eco-system service payments [54,55]. Specialization is an alternative approach taken by some farmers, concentrating exclusively on one farming enterprise, as a polar opposite to diversification [55]. However, concerns have been raised around the environmental impact and the pressure on biodiversity that specialization, production intensity and mono-cultures can enact [56,57], but these concerns are contested by others within the concept of sustainable intensification [58,59,60,61]. Regional specialization can drive efficiency e.g., centered around a dairy processing plant or poultry slaughter plant, and this can influence a farming enterprise as they look to repivot or develop their enterprise portfolio. These farm enterprise strategies are business- and business-resource-specific and one aspect that is key to adopting entrepreneurial specialization, diversification or pluriactivity is the availability of appropriate human capital in terms of knowledge, skills and competences.

Entrepreneurial legacy: The topic of entrepreneurial legacy is a contemporary theme in the literature [62] and an important factor in the development of the curriculum for agricultural and land-based universities and colleges and agri-technology business incubators and accelerators. Entrepreneurial legacy relates to how entrepreneurial propensity and practice is developed, nurtured and generated within families and transmitted trans-generationally [62,63,64,65]. Thus, despite some learners not having a theoretical awareness of entrepreneurship per se, nor buying into entrepreneurial ideology, they have been raised in an entrepreneurial farming family and as a result have an entrepreneurial mindset and innate entrepreneurial skills that they are able to tap into during their studies by drawing upon different spheres of influence [66,67]. Consequentially, entrepreneurial legacy is a rhetorical reconstruction that manifests itself as a narrative relating to past entrepreneurial achievements and resilience in the form of story-telling [63]. This script-based narrative motivates and gives meaning to entrepreneurial behaviors that are in effect imprinted upon the next generations who are able to understand and seize entrepreneurial opportunities [68], because of the imprinting process [66]. Imprinting results from the profound influence of the social and historical context, mediated by the counter-balancing process of reflexivity [68]. Entrepreneurial legacy can also mean that parents nudge their children towards educational and work experiences that either mirror their own and/or that they perceive as high quality and suitably related to the family business [69]. Entrepreneurial legacy with agricultural businesses can also influence access to capital and social networks [70], perceived behavioral support [71] and social learning [69].

Entrepreneurial Bridging: The concept of bridging between entrepreneurial forms of organization is not a new area of interest [72]. However, the under-researched and under-appreciated role of entrepreneurial bridging in farming is an important element of entrepreneurial education because, as with entrepreneurial legacy, it may be innate within the farming community. Entrepreneurial bridging relates to the practices of pluriactivity and diversification as well as bricolage [73] and involves “taking between” discrete entrepreneurial spheres of opportunity [74]. Entrepreneurial bridging in the agricultural sector occurs by nurturing entrepreneurship in younger generations by multiple generations working side by side within a family business [67]. This makes the topic of bridging of importance as it offers another route into farming in that individual may make their first entrepreneurial endeavor in one business to then transition that capital into an existing rural family business.

Ecopreneurship and environmental sustainability: This involves the emerging sub-topics of ecopreneurship, as in the entrepreneurship of ethics and place [75,76], organic entrepreneurship and “green entrepreneurial farming” [77,78]; regenerative agricultural entrepreneurship [79]; and sustainable rural entrepreneurship [80]. There is a growing pressure to boost entrepreneurial orientation to produce food naturally without depleting natural resources [78]. This entails the amendment, replacement or co-existence of traditional agricultural practices and knowledge with new ideas and ways of thinking and potentially a return to pre-industrial forms of farming and a rejection of exploitative forms of food production [81], i.e., a process of regrounding. The movement espouses new business models to achieve profitable but responsible farming practices [82]. This emergent literature is set against a backdrop of contemporary environmental problems and climate change issues facing the world. Schaltegger [11] (p. 47). states:

“Ecopreneurship is characterized by some fundamental aspects of entrepreneurial activities that are oriented less towards management systems or technical procedures and focused more on the personal initiative and skills of the entrepreneurial person or team to realise market success with environmental innovations.”Ecopreneurs therefore often embed personal mission, beliefs and drivers in their business activities e.g., to reduce food loss and food waste, packaging use, improve animal welfare or reduce the ecological footprint of food production. This ethos mirrors that of the family farmer where often personal self-identity and business identity coalesce.”[46]

The entrepreneurship-dyslexia-farming nexus: This nexus links entrepreneurial propensity to the everyday skills, behaviors and practices of farmers [81,83]. In the wider entrepreneurship literature, the connection between entrepreneurship and dyslexia has been studied [84,85]. One study in the US found that 35% of those who identified as entrepreneurs had dyslexic tendencies compared to 1% of corporate managers [84]. However, in a study from the Netherlands, no significant relationship was found between entrepreneurship and dyslexia [86]. The incidence of dyslexia in the farming industry is significantly higher than in the average population [81]. The familial pattern of dyslexia has also been highlighted in one study of church records where the relationship for dyslexics living today could be traced eight generations, but this pattern was not consistent [87]. This imbalance has been recognised by the National Farmers Union Scotland [NFUS], Dyslexia Scotland, the Scottish Rural Universities and Colleges [SRUC]. Suggestions that dyslexic students permeate towards agricultural subjects because they perceive the industry as relying less on written language and the proportion of students with dyslexia on food and agriculture courses sits at around 20% in the UK [88,89]. There are a number of inter-linked reasons why suspected incidences of dyslexia may be higher than average within the farming community [81]. These include the fact that, traditionally, due to high land costs and the nature of land ownership, farming has been a privileged occupation open mostly to the sons and daughters of established farming and land-owning families. This has meant that many farming families have farmed their holdings for several generations with stewardship of the land being passed down from generation to generation. Entrepreneurial legacy and bridging means the children of the land are raised and socialized from an early age to work outdoors, spending evenings, weekends and holidays at work. This may suggest that there are nuanced social and cultural factors within a farming community that play a role in the entrepreneurship-dyslexia-farming nexus. Whilst the farming-dyslexia nexus has emergent literature as a discipline, there are no academic studies that consider the ecopreneurship-dyslexia nexus, and this would be worthy of further study.

A spiral curriculum has “an iterative revisiting of topics, subjects or themes throughout the course” [90] (p. 141). The researchers further argue that as topics are revisited, the level of difficulty in terms of knowledge, skills or demonstrable competencies increases and the role of the teacher/mentor is to relate new learning to previous activities so ultimately there is learning progression [91]. By using the term “spiral pedagogies,” we extend beyond the accepted definition to consider that agricultural, farm business and agri-business courses need to draw upon the innate entrepreneurial knowledge of the students by tapping into aspects of social learning, entrepreneurial legacy and entrepreneurial bridging i.e., to develop active learning activities to reflect the already learned and developed understandings of agriculture via family-immersion in entrepreneurial legacy and bridging as sons and daughters of the farm. Sub-consciously, learners gain positive lessons via experiential learning from generations of entrepreneurial farmers especially through being nurtured in entrepreneurial families and households where entrepreneurship is an ever present albeit silent ideology or ethos. The value of circular curricula has been linked with vocational training and the development of entrepreneurial skills [92]. In summary, innovation ecosystems are of particular interest when considering entrepreneurial aspects of the agri-food and wider rural economy. Entrepreneurship clubs within a university can develop an ecosystem for entrepreneurial learning [93] and this can be extended to the context of a business incubator and accelerator and also the notion of a living lab. A living lab is “a physical or virtual space in which to solve societal challenges, especially for urban areas, by bringing together various stakeholders for collaboration and collective ideation” [94] (p. 976).

Overcoming the so-called “valley of death” of innovation requires not only the bridging between the research sphere and the commercial sphere [95], but also consideration of existing constructs of entrepreneurial bridging and legacy and its influence, or not, on the learned experience and the re-learned experience of fledgling and engaged entrepreneurs and ecopreneurs. Central to this is the connection between creativity and novelty seeking i.e., the quest for looking for what is new or different [96], which is of particular interest when considering entrepreneurial behavior. This paper seeks to examine the different dimensions of ecopreneurial education, both within and aligned to the university setting, but particularly the need to change traditional ways of thinking about farming practices and processes that must be underpinned by activities that promote ecopreneurship behavior and the enabling of the bringing to market of new ideas technological solutions. Clear processes must be in place to achieve these outcomes that are agile and reactive to individual and collective societal and business needs.

3. Materials and Methods

To date, there has been a dearth of research into entrepreneurship education within the agriculture and land-based university sector and, specifically, what exactly does entrepreneurship mean in its unique sectoral context [67,97,98]. Agricultural and land-based universities (and colleges) play a major part in educating farmers and the future employees of such businesses into farming ways and practices [97]. The “patchwork” educational system emerged from the historic need for the provision of local agricultural colleges within most counties in the United Kingdom (UK). Three former colleges have more recently been awarded university status: The Royal Agricultural University (RAU), Harper Adams University (HAU), and the Scottish Rural Universities and Colleges and, in the last year, a fourth, Hartpury University. Some non-agricultural universities have a longstanding tradition of agricultural science and agriculture learning and research activity such as the Universities of Nottingham, Reading, Edinburgh, Newcastle and Aberystwyth.

The methodology used in this research is qualitative in nature and is based upon a qualitative, critical review of the literature aided by the use of documentary research [99] in relation to the examination of prospectus, curriculum development and websites at agricultural education institutions via the active process of netnography [100]. From this dual methodological approach, data are mined and then used to generate a case story [101] of enterprise and entrepreneurship education at these institutions. Following the literature review outlined in the introduction, secondary data was used to determine the degree to which individual BSc degree or one year top-up courses listed on the WhatUni site in May 2019 contained the following key words in their titles “agricultural science”, “agriculture”, “agri-business”, “agri-food”, “agricultural management”, “applied farm management” and “international business including agri-business”.

The courses identified (n = 71) were then analyzed at the module level (Table 1) for explicit use of the following terms: “business”, “business development”, “entrepreneurship”, “enterprise”, “innovation”, “diversification”, “information systems”, “communication technology”, “agri-technology”.

Table 1.

Indicative module content for agricultural degrees analyzed on WhatUni website.

Further analysis of course details was undertaken to see in which institutions the courses covering innovation, diversification and entrepreneurship and enterprise courses were on offer (Table 2).

Table 2.

Topics covered on agricultural and applied farm management courses.

Theoretical and Conceptual Underpinnings and Frameworks for Action

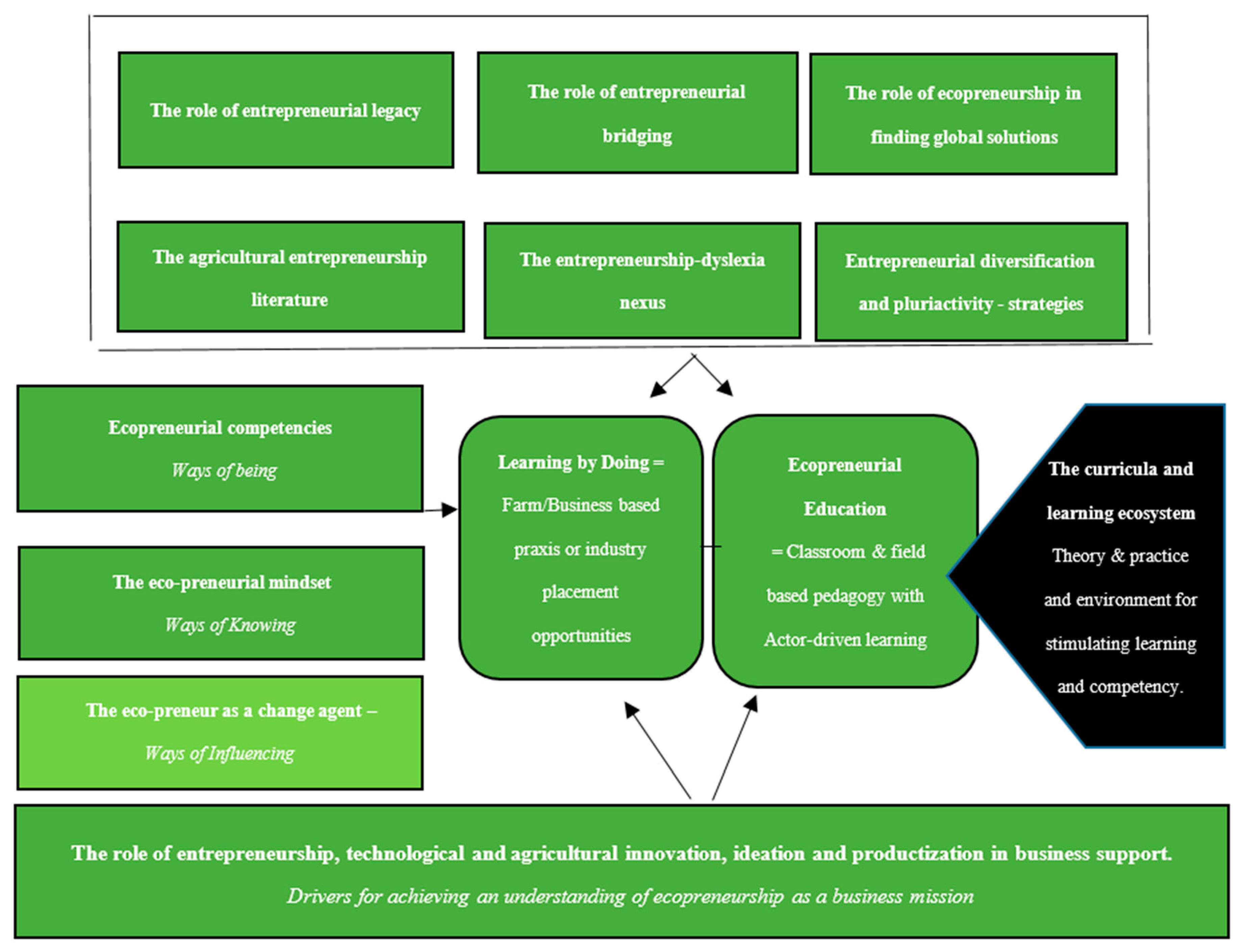

Emerging themes from the literature review and the posited linkage informed a theoretical framework that was then used to ground the findings (Figure 1). A case study was then used to explore the entrepreneurial transition within the university context from undergraduate program through to business incubator. The university of interest here is the Royal Agricultural University (RAU).

Figure 1.

Ecopreneurial education and business support: theoretical framework.

4. Results and analysis

4.1. Course Offering

The review of the courses on offer (n = 71) shows the majority of the courses were titled as agriculture (n = 48), agricultural science (n = 12) and business or management courses (n = 11); see Table 1. Only one course covered agri-technology as a title in the course, and at modular level there was limited articulation of innovation (n = 3), information systems and communication technology (n = 4), diversification (n = 5); both more widely entrepreneurship and enterprise (n = 13). The term ecopreneurship is not reflected in any of the course offering titles and the degree or the module level. Whilst HAU does not have a specific entrepreneurship module, the one-year compulsory work placement has been shown to increase entrepreneurial attitude of the students that participated. Manning and Parrott’s [69] study showed that weighted mean entrepreneurial attitude increased after placement for all students (n = 108) even when 77% of the students already came from a self-employed or entrepreneurial background and the agricultural students mean weighted entrepreneurial attitude was higher than all other students on different programs.

Two institutions, Duchy College and the RAU, have embedded themes of entrepreneurship, enterprise, innovation, diversification, agri-technology and information systems into their undergraduate programs, but this shows limited engagement in higher education as a sector across the learning provision with themes that could promote entrepreneurship and ecopreneurship.

Although agricultural entrepreneurship, agri-technology and ecopreneurship as academic disciplines are in its infancy, there are various streams of literature that are capable of being synthesized into a research-informed working-curricula. At present, the sub-strands of rural entrepreneurship, strategy and innovation have limited traction within the traditional university curriculum and they are rarely taught as a discrete corpus of knowledge. A specific case study is now considered of how entrepreneurship can be embedded into the curricula and also aligning the university with business incubation and acceleration.

4.2. Royal Agricultural University (RAU): Case Study

The RAU was established in 1845 and has provided land-based education for the last 175 years and currently has around 1200 students [102]. Entrepreneurship is embedded in the curriculum and there is a specific business school concentrating on entrepreneurship and other business-related topics. At the RAU, the 2020 prospectus outlines an over-arching entrepreneurial ethos to “Create your own path” [102]. The marketing legend in the prospectus brochure claims:

“We pride ourselves on creating the knowledge and industry connections which stem from our rich heritage with an innovative, forward thinking and enterprising approach. It is our proven combination which continues to open doors for our students. RAU graduates have prepared for successful careers in their chosen field whether that be leading innovation and change in industry, informing future land-based policy or setting up their own businesses; which many of our entrepreneurial students do with great success.”

The RAU delivers a variety of undergraduate degrees at BSc and FdSc level, including degrees in business innovation and business management, and these themes are incorporated in wider modules. This theme is continued through the taught MSc provision. The narrative from the university highlights “Fresh thinking for land-based business” and the marketing legend continues:

“We place a strong emphasis on entrepreneurialism, creating opportunities for our students to develop their own business ideas and receive tailored support. From student societies to workshops and awards budding entrepreneurs can benefit from the knowledge and experience of their lecturers and strong industry ties.”

Indeed, the core of this is the RAU Enterprise and Entrepreneurship Programme [103]. The focus is upon supportive learning guided by lawyers, insurers, marketing professionals and accountants. The program claims to be a “springboard” for the business leaders of tomorrow. This is achieved via the innovative use of networking events, workshops, mentoring services, work placements and inspirational talks by entrepreneurs. The layered learning opportunities and resources for RAU students have been collated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Entrepreneurship learning opportunities and resources at the RAU.

Students have access to the Farm491 business incubator and accelerator [104]. Farm491′s operational model focuses on transitioning an entrepreneurial idea through the “valley of death” to a business that is market-ready. Agri-food is a complex sector, highly driven by business to business (B2B) relationships and commercial associations, making the “valley of death” very wide. The main challenges to translating from ideation to commercialization and business and personal development are lack of entrepreneurial learning time pressures, lack of skilled employees who can come into the business and the need for better communications and less so lack of advice and support and weak alignment between the product/service and the market [105,106]. Farm491 takes an intentionally non-linear approach to supporting entrepreneurs, informed by design thinking principles, where an entrepreneur can plug into each component of the Farm491 incubator offer, allowing for a highly targeted approach to each individual entrepreneur and their needs.

Farm491 does not create new technologies: it is instead focused on the productization of technology to increase the adoption of innovation into the sector [104]. Productization is a strong body of literature and is only considered in overview here. In simple terms, productization is the act of modifying something to realign it as a commercial product [107]; the commercial function is involved in creating and updating a business offering in response to market opportunity and need through a credible, consistent, standardized and tangible offering that is easy to sell, purchase and use [108,109]. Productization also differentiates clearly between the product and the business [108]. Productization of a service can improve customer understanding and business skills [110], competitiveness, performance, transfer of knowledge and more effective division of work and can be focused on a minor part or indeed the whole offering [111]. Productization is directed by core values, where success is ultimately defined by helping the commercialization of agri-technology ideas in a way that helps shift the food system to be more socially and environmentally sustainable. This is underpinned by the belief that the most scalable viable businesses will have some level of impact at their core. Ecopreneurs are motivated by five factors: their green values; passion; being their own boss; earning a living; and seeing a gap in the market for their product/service [112]. Ecopreneurs have also been described as eco-conscious change agents [113], albeit through a tempered path [114]. These values align with the values of Farm491 to empower farmers, build climate resilience and empower consumers (https://farm491.com). Therefore the “impact story,” i.e., the accompanying business mission and narrative of how the innovation will influence the sector in terms of productization, is as necessary as the business fundamental of how to become a viable business. The Farm491 offer has four broad components:

- Immersive & diverse innovation ecosystem: There is an intentionally broad ecosystem within the Farm491 membership (https://farm491.com/type/current/) ranging from small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to large industry players. This environment empowers entrepreneurs to understand the needs of industry to ensure the product being developed actually solves a problem or delivers economic, environmental value that industry is prepared to pay for. The current active membership is 70 companies, and students at the RAU have the opportunity to interact with, and learn from, these businesses. Farm491 utilizes thought leadership discussion and showcase events to bring together this diverse ecosystem around key and emergent topics.

- Non-time-based graduation process: The “valley of death” from ideation to commercialization within a complex industry like the agri-food industry is very wide. Farm491 has develop a “long-tail” support network that includes physical spaces, from hot-desking to large offices to industrial workshops, enabling Farm491 to offer spaces appropriate for the stage of the company and different levels of support depending on the stage of the business.

- Influencing Funders: Farm491 provides informal and formal advice to funding bodies (public, philanthropic and investment) to help align their diligence process and understanding of the innovation landscape with the needs of entrepreneurs. The embedding of advanced agri-technology in the Gloucestershire draft Local Industrial Strategy [115] is a result of such activity. Engagement with policy makers and funders helps break down the barriers to investment in a nascent sector such as agri-technology. As a result, Farm491 has helped entrepreneurs raise over £31 million in funding since 2018.

- Enabling merging of innovation: Farm491 takes an active role of connecting different entrepreneurs together, encouraging collaboration to drive fewer but more commercially focused ideas forward at scale.

To build a vibrant innovation ecosystem, student membership of Farm491 is free and Farm491 maintains around 20% of members that are part of the incubator coming from the RAU student population. This provides an entrepreneurial journey through student enterprise and entrepreneurial programs through to full ideation and commercialization, whilst still having access to many of the mentors that form the academic body of the university. The RAU is unique in this higher education offering in agri-technology and agri-business entrepreneurial support. In line with the RAU knowledge exchange pedagogical model, there is a collaborative approach between Farm491 incubation, student enterprise and the teaching. Central to this is the building of entrepreneurial curiosity by presenting to students the challenges of the food system and the role innovation can play, and Farm491 being actively involved in the Grant Idea challenges. In 2019, these activities led to engaging with 148 students around agri-technology. Farm491′s free membership offering to the incubator encourages the update of the services. These include access to a knowledge toolkit that includes expert knowledge around entrepreneurship within agri-technology and access to business mentors. This case study from the RAU shows the adoption and implementation of Figure 1 as described earlier this paper. The key theoretical and conceptual underpinnings for an ecopreneurial education in action is explored in the next section of the paper.

5. Discussion

There are a number of contemporary literatures of interest that are considered: agricultural entrepreneurship, agri technology, the entrepreneurial farmer, rural entrepreneurship more widely, and then the specific aspects of entrepreneurial legacy and entrepreneurial bridging. Whilst entrepreneurial legacy is considered in current literature in terms of development and nurturing generational entrepreneurial behavior with families [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70], what has been identified in this paper is how a university with an agri-technology incubator can in itself develop an ecosystem of entrepreneurial legacy. This is especially so when there is an interaction between existing students and businesses that are at all different stages on the ideation to fully commercialized journey. The literature on entrepreneurial legacy describes the narrative and the rhetorical reconstruction of entrepreneurial activities through storytelling [63] and it is this narrative that can be developed within the incubator ecosystem that gives meaning to entrepreneurial behaviors and also provide the insight to identify entrepreneurial, and in this case ecopreneurial, opportunities. Entrepreneurial bridging has also been considered within the farming community i.e., where multiple generations come together in an environment to drive entrepreneurial behavior [67,72]. Again, the design of the ecosystem at Farm491 allows for this entrepreneurial bridging to occur either from academics or existing and emerging businesses. This study has considered in particular ecopreneurship and the combination of personal mission and beliefs with the designed impact of the product or service developed within the business [8]. It is this ecopreneurial mindset that will allow for a network of businesses to come together to co-develop beneficial solutions and provide disruptive change and much needed transformations [11].

Figure 1 provides a theoretical framework for ecopreneurial education and business support that informs the positioning of this paper. This is a contribution to existing knowledge in the field. The framework demonstrates the theoretical and conceptual underpinnings of the model in terms of existing entrepreneurial literature. Central to the framework is how the curricula and learning ecosystem whether within the university or in a business incubator is designed and operationalized. Key to this process is to stimulate learning and develop competencies [96]. However, none of the courses examined in this study described ecopreneurship explicitly either in the course or module titles, so there is limited inference or visibility that this specific framing of entrepreneurship or indeed entrepreneurship or the promotion of entrepreneurial behavior is included within the course. Consideration should be given within academia to how ecopreneurship can be embedded in courses in the future and also signposted to prospective and existing students.

The entrepreneurship-dyslexia-farming nexus is considered and how pedagogic framing is crucial to learning and personal development [83,84,85]. As described previously in the literature review, whilst the farming-dyslexia nexus is an emergent literature, there are no academic studies that consider the ecopreneurship-dyslexia nexus. The entrepreneurship-dyslexia nexus informs the design of ecopreneurial education, whether this is classroom-based, field-based or actor-driven learning. Whilst studies have not considered ecopreneurial education specifically they suggest that dyslexic students favor visuospatial and kinesthetic learning styles [116]. Indeed, some studies suggest that dyslexic students have superior visuospatial skills [117], particularly males [118], and they are over-represented in the visual and creative arts [119]. The pedagogy that underpins agricultural and land-based focused education is crucial because it is based on learning by doing. Learning by doing can be via a formal business-based praxis such as the enterprise to entrepreneurship program at the RAU or via the placement opportunities that are provided by many agricultural and land-based universities and colleges. However, ingrained practice, habits, attitudes and perceived behavioral control may make it difficult for students to be open-minded to “new ways of doing” or to accept innovation, thus influencing both their cognitive and affective engagement with the learning experience. The learning needs to drive ecopreneurial competencies (the ways of being), ecopreneurial mindset (the ways of knowing) and as an ecopreneur the ability to develop solutions (the ways of influencing). The drivers for achieving an understanding of ecopreneurship as a business mission involve consideration of the role of ecopreneurship and how that interacts with technological and agricultural innovation, and the ways to drive projects from ideation through to commercialization through productization is enacted in terms of individual ecopreneur support or indeed wider business support.

From an examination of the curricula and the learning ecosystem at the RAU, it is evident that although entrepreneurship is embedded in the educational experiences of the students it is achieved via what we refer to as “spiral pedagogies” and learning by doing and developing, as highlighted in the framework, ways of being, ways of knowling and ways of influencing. This conceptual paper has considered the nature of explicit and implicit discourse around entrepreneurship with specific focus on ecopreneurship. In order to provide such education and business support, an institutional framework must be in place within a university to effectively facilitate and enhance the “quadruple interface” of academic, institutional structures, business and ecopreneurial behavior [67]. However, the case study approach has limitations and further empirical work is required to gain an understanding of the learners perspective and the contribution of the learning experience.

Productization is a key aspect of ensuring that a technology or service can transition through the “valley of death” from ideation to full commercialization [108,109,110]. Productization creates an understanding of the difference between the identity of the product or service and the business and developing a credible, consistent offering that is valued by the market. Ecopreneurial productization is underpinned by core values and these values themselves can create product value in the marketplace. These values can include personal values and values associated with the product such as ecological or social outcomes. The impact story is a crucial element of such product/service positioning in the marketplace. Farm491 is used as a case study within this paper to demonstrate the processes that need to be involved to support businesses in the ecosystem of an agri-technology business incubator. The embedding of an incubator within an agricultural and land-based university means that the university can offer a unique higher education pedagogy and tailored business support. These principles of practice are an intrinsic feature of the activities of the programs and the business incubator and enable learners and businesses alike to drive outcomes that are agile and reactive and meet individual and collective societal and business needs.

6. Conclusions

There is a need for management involved in agriculture, agri-technology and agri-business education to be more entrepreneurial themselves and display courage, ambition and innovation ability in how they evolve the curriculum. The curriculum should include programs in non-agricultural domains such as entrepreneurship [120,121], reflect the needs of the work environment and job market needs [122] and also provide learning experiences through ecosystems such as entrepreneurship clubs, living labs or access to business incubators and accelerators. Indeed, specialist agricultural universities need to demonstrate that they consistently meet or exceed government’s, research community’s, employers’ and society’s expectations in terms of developing economic and social entrepreneurial skills in their student body [67].

Central to ecopreneurial innovation and the drive for sustainable development is the concept of the living lab that combines real-life environments, appropriate activities, multi-actor engagement and inherent methods, tools and approaches that can test products and services in order to drive innovation and deliver solutions to real problems [94]. This is essential when considering the need for sustainable transition and the need to drive innovation and new ways of doing and knowing and being. The entrepreneurial university context provides opportunity for the development of living labs that also deliver experiential learning experiences as part of an embedded spiral curricula. This paper considers ecopreneurial education and business support and how innovators are supported today and also developing the innovators of tomorrow. In many agricultural curricula, there is limited pedagogic framing of learning by doing, but, more specifically, actor-driven and reflective experiential learning, and this needs to change. From a pedagogical perspective, it is incumbent to develop new conceptual, methodological and theoretically underpinned spiral pedagogies to teach and support future generations of learners at our agricultural and land-based colleges and universities how to exploit and take advantage of such entrepreneurial and ecopreneurial opportunities. Productization, too, needs to be embedded into the ecopreneurial pedagogy and also how businesses and their associated ecopreneurs navigate from ideation to successful product/service commercialization.

This paper has considered pedagogic and program design both inside an academic curriculum and also in the development and operalization of an agri-technology incubator. Key to this work has been consideration of a university case study to explore these areas of interest and provide insight into how progress from ideation to commercialization can be more readily supported in a university setting especially in the context of sustainable transition. Why is this an important area of research? Technological improvements are critical in the agri-food sector and wider land management if we are to drive production efficiency, seek reduction in emissions and address climate change and provide incremental and system level benefit to offset the global human impact on the planet’s resources and ecosystem. This paper contributes to the body of knowledge on the role of universities in supporting entrepreneurial and econpreneurial development especially in the rural economy. This study has considered UK institutions and it would be interesting to consider this subject at a global scale in order to inform best practice. More research should also be undertaken into the pedagogic processes that inform both for learners and to consider the attitudes of business leaders especially seeking evidence of the efficacy of the approach of learning by doing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and L.M.; methodology, R.S. and L.M.; formal analysis, L.M.; investigation, L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., L.M. and G.C.; writing—review and editing, R.S., L.M. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This paper has iteratively developed from a conference paper presented in June 2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vergragt, P.J.; Dendler, L.; De Jong, M.; Matus, K. Transitions to sustainable consumption and production in cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekhof, M.-C.; Regnier, E.; Quaas, M.F. Economic growth, international trade, and the depletion or conservation of renewable natural resources. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 97, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaca, C.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Psomas, E.L.; Ormazabal, M. What should consumer organizations do to drive environmental sustainability? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future Acronyms and Note on Terminology Chairman’s Foreword; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grin, J.; Rotmans, J.; Schot, J. Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long Term Transformative Change; Routledge: Abington, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschmayer, F.; Bauler, T.; Schäpke, N.N. Towards a thick understanding of sustainability transitions—Linking transition management, capabilities and social practices. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 109, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaak, R. Green logic: Ecopreneurship, Theory and Ethics; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hultman, M.; Nordlund, C. Energizing technology: Expectations of fuel cells and the hydrogen economy, 1990–2005. Hist. Technol. 2013, 29, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolin-Lopez, R.; Martiínez-del-Rio, J.; Céspedes-Lorente, J.J. Environmental entrepreneurship: A review of the current conversation after two decades of research. In Proceedings of the 2014 GRONEN Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 16–18 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S. A Framework for Ecopreneurship. Greener Manag. Int. 2002, 2002, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, T.; Hultman, M. Ecopreneurship—Assessing the field and outlining the research potential. Small Enterp. Res. 2016, 23, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, M.; García, M.G.; Carrilero-Castillo, A. An Overview of Ecopreneurship, Eco-Innovation, and the Ecological Sector. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerswald, P.E.; Branscomb, L.M. Valleys of Death and Darwinian Seas: Financing the Invention to Innovation Transition in the United States. J. Technol. Transf. 2003, 28, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, H.; Chung, Y.; Yoon, S. How can university technology holding companies bridge the Valley of Death? Evidence from Korea. Technovation 2020, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.H.; Baker, T.; Markham, S.K.; Kingon, A.I. Bridging the Valley of Death: Lessons Learned From 14 Years of Commercialization of Technology Education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2009, 8, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellwood, P.; Williams, C.; Egan, J. Crossing the valley of death: Five underlying innovation processes. Technovation 2020, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratinho, T.; Henriques, E. The role of science parks and business incubators in converging countries: Evidence from Portugal. Technovation 2010, 30, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergek, A.; Norrman, C. Incubator best practice: A framework. Technovation 2008, 28, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemans, W.G.; Huizingh, K.R.E. Rethinking the Valley of Death; an Ecosystem Perspective on the Commercialisation of New Technologies. Technovation 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S. The indigenous rural enterprise characteristics and change in the British farm sector. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1996, 8, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S. Portfolio entrepreneurship in the farm sector: Indigenous growth in rural areas? Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1998, 10, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S. Multiple business ownership in the farm sector: Assessing the enterprise and employment contributions of farmers in Cambridgeshire. J. Rural. Stud. 1999, 15, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, S.L. Entrepreneurship in the farm sector: Indigenous growth for rural areas. In Entrepreneurship in Regional Food Production; Norland Research Institute: Bodo, Norway, 2003; pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.; Rosa, P. Indigenous Rural Firms: Farm Enterprises in the UK. Int. Small Bus. J.: Res. Entrep. 1998, 16, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.C.; Tiwari, R.; Sharma, J.P. Entrepreneurship in Livestock and Agriculture; CBS Publishing: New Dehli, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alsos, G.; Welter, F.; Carter, S.; Ljunggren, E. The Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship in Agriculture and Rural Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fitz-Koch, S.; Nordqvist, M.; Carter, S.; Hunter, E. Entrepreneurship in the Agricultural Sector: A Literature Review and Future Research Opportunities. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2017, 42, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lans, T.; Van Galen, M.; Verstegen, J.; Biemans, H.; Mulder, M. Searching for entrepreneurs among small business ownermanagers in agriculture. NJAS—Wageningen. J. Life Sci. 2014, 68, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lans, T.; Seuneke, P.; Klerkx, L. Agricultural Entrepreneurship. In Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Carayannis, E.G., Ed.; Springer: New York, USA, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, C.S.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Ferreira, J.J. What’s new in the research on agricultural entrepreneurship? J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 65, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omodanisi, E.O.; Egwakhe, A.J.; Ajike, O.E. Smart Agri-Preneurship Dimensions and Food Affordability. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2020, 20, 1–9. Available online: https://journalofbusiness.org/index.php/GJMBR/article/view/3053/2954 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- McElwee, G. Farmers as entrepreneurs: Developing competitive skills. J. Dev. Entrep. 2006, 11, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, G. A taxonomy of entrepreneurial farmers. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2008, 6, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.D.; Rosenzweig, M.R. Learning by Doing and Learning from Others: Human Capital and Technical Change in Agriculture. J. Politi -Econ. 1995, 103, 1176–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gasson, R. Educational qualifications of UK farmers: A review. J. Rural. Stud. 1998, 14, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P.; Smith, R.; McElwee, G. The dark side of the rural idyll: Stories of illegal/illicit economic activity in the UK countryside. J. Rural. Stud. 2015, 39, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pato, M.L.; Teixeira, A.A. Twenty Years of Rural Entrepreneurship: A Bibliometric Survey. Sociol. Rural. 2014, 56, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Korsgaard, S. Resources and bridging: The role of spatial context in rural entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 30, 224–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaddefors, J.; Anderson, A. Romancing the rural: Reconceptualizing rural entrepreneurship as engagement with context(s). Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2018, 20, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Kimmitt, J. Rural entrepreneurship in place: An integrated framework. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 842–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, E.; Casais, B.; Silva, J. Local development through rural entrepreneurship, from the Triple Helix perspective. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, R.R. Factors Affecting Rural Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. Manag. 2020, 3, 239–240. Available online: https://www.journals.resaim.com/ijresm/article/view/168 (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Bosworth, G.; McElwee, G.; Smith, R. Rural enterprise in Mexico: A case of necessity diversification. J. Enterp. Commun. People Places Glob. Econ. 2015, 9, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, W.; Henley, A.; Dowell, D. Farm diversification, entrepreneurship and technology adoption: Analysis of upland farmers in Wales. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 53, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calza, F.; Go, F.; Parmentola, A.; Trunfio, M. European rural entrepreneur and tourism-based diversification: Does national culture matter? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; McElwee, G.; Smith, R. Farm diversification strategies in response to rural policy: A case from rural Italy. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumenihelali, H.; Sadighi, H.; Chizari, M.; Abbasi, E. Pluriactivity: An Entrepreneurial Strategy for Smallholder Farmers. J. Entrep. Agric. 2020, 6, 112–124. Available online: http://jea.sanru.ac.ir/article-1-204-en.html (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- De Silva, L.R.; Kodithuwakku, S.S. Pluriactivity, entrepreneurship and socio-economic success of farming households. In The Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship in Agriculture and Rural Development; Alsos, G.A., Carter, S., Ljunggren, E., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alsos, G.A.; Ljunggren, E.; Pettersen, L.T. Farm-based entrepreneurs: What triggers the start-up of new business activities? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2003, 10, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rønning, L.; Kolvereid, L. Income Diversification in Norwegian Farm Households. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2006, 24, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsos, G.A.; Carter, S.; Ljunggren, E. Kinship and business: How entrepreneurial households facilitate business growth. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ploeg, J.D.; Roep, D. Multifunctionality and rural development the actual situation in Europe. In Multifunctional Agriculture. A New Paradigm for European Agriculture and Rural Development; Van Huylenbroeck, G., Durand, G., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2003; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Meraner, M.; Heijman, W.; Kuhlman, T.; Finger, R. Determinants of farm diversification in the Netherlands. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, J.; Limburg, E.K.; Rydberg, T. Impact of production intensity on the ability of the agricultural landscape to generate ecosystem services: An example from Sweden. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roest, K.; Ferrari, P.; Knickel, K. Specialisation and economies of scale or diversification and economies of scope? Assessing different agricultural development pathways. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 59, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Garnett, T. Food security and sustainable intensification. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20120273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Williams, J.; Daily, G.; Noble, A.; Matthews, N.; Gordon, L.; Wetterstrand, H.; Declerck, F.; Shah, M.; Steduto, P.; et al. Sustainable intensification of agriculture for human prosperity and global sustainability. Ambio 2017, 46, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Benton, T.G.; Bharucha, Z.P.; Dicks, L.V.; Flora, C.B.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Goulson, D.; Hartley, S.; Lampkin, N.; Morris, C.; et al. Global assessment of agricultural system redesign for sustainable intensification. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, L.; Verburg, P.; Schulp, C. Opportunities for sustainable intensification in European agriculture. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 48, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskiewicz, P.; Combs, J.G.; Rau, S.B. Entrepreneurial legacy: Toward a theory of how some family firms nurture transgenerational entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, F.; Stamm, I.; DeWitt, R.-L. The Development of an Entrepreneurial Legacy: Exploring the Role of Anticipated Futures in Transgenerational Entrepreneurship. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 352–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, E.; McAdam, M.; Gamble, J.R.; Brophy, M. Entrepreneurial learning: The transmitting and embedding of entrepreneurial behaviours within the transgenerational entrepreneurial family. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.D.; Hamilton, E.; Jack, S.L. Understanding entrepreneurial opportunities through metaphors: A narrative approach to theorizing family entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, B.D.; Williams, D.W.; Smith, A.R. Entrepreneurial inception: The role of imprinting in entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L. Enabling entrepreneurial behaviour in a land-based university. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Bruton, G.D.; Si, S.X. Entrepreneurship through a qualitative lens: Insights on the construction and/or discovery of entrepreneurial opportunity. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; Parrott, P. The impact of workplace placement on students’ entrepreneurial attitude. High. Educ. Ski. Work. Learn. 2018, 8, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, S.C.; Maat, S.M.; Mohd, N. Identifying Factors that Affecting the Entrepreneurial Intention among Engineering Technology Students. Procedia -Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambad, S.N.A.; Damit, D.H.D.A. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intention Among Undergraduate Students in Malaysia. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N.; Jarvis, O. Bridging Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Creation of New Organizational Forms: A Multilevel Model. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, S.; Müller, S.; Tanvig, H.W. Rural entrepreneurship or entrepreneurship in the rural—Between place and space. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2015, 21, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, F. Economic Spheres in Darfur. In Themes in Economic Anthropology; Firth, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, A.E. Reflections on Eco-Preneurship. 2012. Available online: File:///C:/Users/rober/AppData/Local/Packages/Microsoft.MicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe/TempState/Downloads/31834%20(2).pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Hugo, A.; Barane, J.; Clemetsen, M.; Reed, S. Eco-preneurship: The Aesthetics of Place Based Education. 2014. Available online: https://naturpedagog.no/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ECOPRENEURSHIP-study-report-.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Rezaei, B.; Naderi, N.; Rostami, S. Strategic analysis of green entrepreneurship development in agriculture (case study: Kermanshah county). Iran. Agric. Ext. Educ. J. 2018, 14, 37–50. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20193131748 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Sher, A.; Mazhar, S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Li, X. Green entrepreneurial farming: A dream or reality? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N.C. Regenerative agricultural entrepreneurship and education along the Petite Cote, Senegal. LEISA Mag. 2006, 22, 26–27. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/96591 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Ratten, V.; Dana, L.-P. Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Family Farms and the Dairy Industry. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, G.; Smith, R.; Smith, A.; McElwee, G. Researching the influence of dyslexia on entrepreneurial propensity in the farming community: A preliminary study. In Proceedings of the Rural Entrepreneurship Conference, Islay, Scotland, 18–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karari, R.; Munyua, M. Entrepreneurship Education and Eco-Preneurship Innovation as Change Agents for Environmental Problems. 2018. Available online: http://ir.mksu.ac.ke/handle/123456780/758 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Smith, R.; Conley, G.; Manning, L. Documenting the role of UK Agricultural Colleges in propagating the ‘farming-dyslexia-entrepreneurship nexus’. In Entrepreneurship, Dyslexia and Education; Pavey, B., Alexander-Passe, N., Meehan, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, J. Analysis of the incidence of dyslexia in entrepreneurs and its implications. In Proceedings of the United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship, San Antonio, TX, USA, 10–13 January 2008; p. 636. [Google Scholar]

- Hewes, D.G. Dyslexia Association of Singapore Entrepreneurs with Dyslexia in Singapore: The Incidence, Their Educational Experiences, and Their Unique Attributes. Asia Pac. J. Dev. Differ. 2020, 7, 157–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; Rietveld, C.A.; Van Der Zwan, P. Unraveling two myths about entrepreneurs. Econ. Lett. 2014, 122, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, I.; Nilsson, L.-G. What church examination records can tell us about the inheritance of reading disability. Ann. Dyslexia 1986, 36, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E. The academic attainment of students with disabilities in UK higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2009, 34, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.M. Listening to the Voice of Dyslexic Students at a Small, Vocational Higher Education Institution to Promote Successful Inclusive Practice in the 21st C. Int. J. Learn. Teach. 2016, 2, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Harden, R. What is a spiral curriculum? Med. Teach. 1999, 21, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; de Kluwe Aguiar, L. Embedding sustainable development in the curricula—Learning about sustainable development as a means to develop self-awareness. In Integrating Sustainable Development into Curriculum; Sengupta, E., Blessinger, P., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff, M.T. Entrepreneurial Thinking and Action—An Educational Responsibility for Europe. Eur. J. vocat. Train. 2008, 45, 5–31. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ836654 (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Pittaway, L.A.; Gazzard, J.; Shore, A.; Williamson, T. Student clubs: Experiences in entrepreneurial learning. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2015, 27, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M. A systematic review of living lab literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucevicius, G.; Juceviciene, R.; Gaidelys, V.; Kalman, A. The Emerging Innovation Ecosystems and "Valley of Death": Towards the Combination of Entrepreneurial and Institutional Approaches. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, K.M.; Nadeau, S.E.; Beversdorf, D.Q. Creative Innovation: Possible Brain Mechanisms. Neurocase 2003, 9, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. Reviewing Entrepreneurship Education in the UK Agricultural College Sector: An Exploratory Study. In Proceedings of the Rural Entrepreneurship Conference, Dumfries, UK, 24–26 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.; Manning, L.; Conley, J. Integrating Entrepreneurship into the curriculum in UK Agricultural Universities. In Proceedings of the Rural Entrepreneurship Conference, Inverness, UK, 17–19 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. A Matter of Record: Documentary Sources in Social Research; John Wiley: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinets, R.V. Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online; Sage: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The Royal Agricultural University Website. Available online: https://www.rau.ac.uk (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Enterprise and Entrepreneurship. The Royal Agricultural University Website. Available online: https://www.rau.ac.uk/study/enterprise-entrepreneurship (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Farm491 Website. Available online: https://farm491.com (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Deakins, D.; Bensemann, J. Entrepreneurial learning and innovation: Qualitative evidence from agri-business technology-based small firms in New Zealand. Int. J. Innov. Learn. 2018, 23, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulvenblad, P.; Barth, H.; Ulvenblad, P.-O.; Ståhl, J.; Björklund, J.C. Overcoming barriers in agri-business development: Two education programs for entrepreneurs in the Swedish agricultural sector. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2020, 26, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkonen, J.; Haapasalo, H.; Hanninen, K. Productisation: A Literature Review. In Diversity, Technology, and Innovation for Operational Competitiveness, Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Technology Innovation and Industrial Management, Phuket, Thailand, 29–31 May 2013; ToKnowPress: Celje, Slovenia, 2013; pp. 3–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hietala, J.; Kontio, J.; Jokinen, J.-P.; Pyysiainen, J. Challenges of software product companies: Results of a national survey in finland. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Software Metrics, Chicago, IL, USA, 11–17 September 2004; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 232–243. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen, T.; Hänninen, K.; Haapasalo, H.; Vehkapera, H.K. Business case analysis in rapid productisation. Int. J. Rapid Manuf. 2014, 4, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valminen, K.; Toivonen, M. Seeking efficiency through productisation: A case study of small KIBS participating in a productisation project. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, N. Productisation of Service: A Case Study. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2012, 3, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J.; Walton, S. What motivates ecopreneurs to start businesses? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastakia, A. Grassroots ecopreneurs: Change agents for a sustainable society. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1998, 11, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, S.; Kirkwood, J. Tempered radicals! Ecopreneurs as change agents for sustainability—An exploratory study. Int. J. Soc. Entrep. Innov. 2013, 2, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- gFIRST Draft Gloucestershire Local Industrial Strategy 2019. Available online: https://www.gfirstlep.com/downloads/2020/gloucestershire_draft_local-industrial-strategy_2019-updated.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Exley, S. The effectiveness of teaching strategies for students with dyslexia based on their preferred learning styles. Br. J. Spéc. Educ. 2004, 30, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attree, A.E.; Turner, M.J.; Cowell, N. A Virtual Reality Test Identifies the Visuospatial Strengths of Adolescents with Dyslexia. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunswick, N.; Martin, G.N.; Marzano, L. Visuospatial superiority in developmental dyslexia: Myth or reality? Learn. Individ. Differ. 2010, 20, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, A.M.; Bennett, S. Dyslexia in Higher Education: The decision to study art. Eur. J. Spéc. Needs Educ. 2012, 28, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etling, A.W.; Barbuto., J.E. Globalizing colleges of agriculture. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Conference of the Association for International Agricultural and Extension Education, Durban, South Africa, 26–30 May 2002; Available online: http://www.aged.tamu.edu/aiaee (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Mulder, M.; Küpper, H. The Future of Agricultural Education: The Case of the Netherlands. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2006, 12, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, J. Study barriers to entrepreneurship promotion in agriculture higher education. Procedia -Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 1901–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).