1. Introduction

The European Commission regularly involves stakeholders when it develops policy and legislation to get support for different European priorities. The added value from their participation in designing policies has been repeatedly emphasized in the documents of the European Union. This participatory approach strengthens commitment as they feel that they are part of a process that not only guarantees transparency but also provides useful elements to highlight strategies through skills and direct experiences. The commission particularly welcomes stakeholders’ ideas and suggestions to design more tailored policies in many different fields. The involvement of both public and private stakeholders (partnership) of a given area as well as a close collaboration between governments and public authorities at the national, regional and local levels represents the basis on which the different development policies are implemented. The partnership, therefore, is seen as a very important multi-actor to listen to for programming at every stage (planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation). Consultation with stakeholders has been a key element also in the process of designing the new Rural Development Programs (RDPs) as far as the 2014–2020 policy round is concerned. This is a European Commission commitment in keeping with the Rural Development Regulation [

1] (EU Reg. n. 1305/2013) under which member states are required to activate consultations during the planning phase of their Rural Development Programs. Furthermore, some other European Union documents [

2,

3] (Article 5 of EU Reg. n. 1303/2013 and Delegated EU Reg. n. 240/2014, and Article 5 of the European Code of Conduct on Partnership) emphasize the advisability of involving all interested stakeholders from the early planning stages and for the whole process with regard to both development of the partnership agreement at the national level and the Rural Development Programs (RDPs) at the regional level.

The design of the proposed measures, in fact, should takes into account the stakeholders’ views. Government and local administrations often make use of support in designing programs and in general in decision-making processes. Some techniques and strategic planning models can be useful to analyze changes and to evaluate the significance of local economy changes and dynamics which are some of the basic information that should be analyzed in order to develop a strategy that could take into account the real needs of a territory and therefore to support its development with tailored policy measures. In recent years, evaluators have expanded their methodological repertoire with designs that include the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods [

4,

5,

6]. The evaluation of a local growth process can be developed through a number of techniques, among which mixed methods are included even if they can show some limitations due to real-world budget, time, data and political constraints [

7,

8]. The decision-making support given to policy makers is based on the information available and on decision alternatives. In many cases, it is necessary to consider a range of problems that could arise by applying non-tailored methodologies to specific environments, such as not only long run effects, quantitative data (un)available and qualitative techniques but also the different stakeholders’ needs and the level of uncertainty of the multiple factors involved in the different phases of the decision process. Hybrid methods, mixed-methods and combination of multicriteria approaches are often used to reach the objective.

This study tries to answer the following research question:

- −

Which are the most important drivers and needs to be addressed when developing the program’s strategy in relation with Priority 1 (P1) “Knowledge Transfer and Innovation”—in particular in relation with focus area 1a (fa1a)—fostering innovation, sustainable innovations, cooperation and development of the knowledge base in rural areas?

This is a very important issue to be addressed by rural development programs which are organized according to the six priorities included in Pillar II of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Through this area of interest, in fact, member states provide measures related to advice, training, cooperation and knowledge transfer. The analysis is focused on a study case, taking into account the results coming from an Italian regional experience within involvement of the local partnership during the planning phase of RDP 2014–2020. This study case at the regional level [

9,

10] allows to highlight the partnership point of view by considering one of the SWOT sets developed around the eighteen focus areas included in the priorities of Reg. (EU) n. 1305/2013 [

1]. During the strategic planning phase of the 2014–2020 programming period, the Friuli Venezia Giulia region, in fact, organized a workshop with some thematic tables dedicated to the priorities of the upcoming program. The results presented here come from a specific thematic table around which experts, representatives of local institutions, associations, cooperatives, consortia, and representatives of universities and research centers discussed in order to identify the most important and urgent needs for the rural world as priority 1 is concerned. Management of the workshops has been prepared using a participatory method; the evidence collection tool was a dynamized SWOT. This is quite interesting considering the increasing role given to society in taking part in strategic planning processes as far as sustainable innovation projects are concerned at the local level. This thematic table has been organized involving experts and representatives of the main public and private local institutions of agricultural, social, environmental, research sectors and educational/advisory organizations. As far as our methodological approach is concerned, a case study approach related to a single Italian region has been considered. If [

11] investigated one of the least developed regions located in the southern part of Italy by applying an exploratory and instrumental method, using the snowball approach to identify the social farms to be included in the study [

12,

13], we analyze a region which belongs to the flourishing northeast which nevertheless shows some discontinuity points with respect to economic weight and production performance, especially with regard to the agricultural sector and the rural areas in general.

2. Background

The methodology applied in our research refers to participatory approaches. There are different types of participatory methods: from focus groups that bring together small groups of people around a specific theme on which they are called to express their opinion to broader and more diverse techniques of community listening. The latter aims to enable consultation of partnerships invested by a policy to include them from the early stages of the building process. Participatory methods are used to gather the opinions of stakeholders and civil society communities to ensure the success of different policies. Some studies emphasize the efficiency related to application of such methods, seeing the involvement of stakeholders as a tool to be used in order to develop a better strategy or to obtain better results [

14].

These methods have found great impetus in rural policies since the ’70s, with Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA) and the with Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) in the ’80s not only to plan development strategies but also to assess the effects of interventions [

15,

16]. Since the ‘80s, these methods have been widely discussed and promoted by [

15,

17,

18,

19,

20] in the fields of agricultural research, natural resource management and rural development. Participatory approaches have become popular in planning and managing policy interventions in a variety of different fields. In rural development policies, the participation of stakeholders and potential beneficiaries of subsidies is nowadays a commitment of the European Commission to achieve better program outcomes and effects. It is the ‘90s that represent a crucial step for a wider dissemination of these methods in development strategies and in its policies application [

21,

22]. The principle from which the participatory approaches are based lies in the possibility given to policy makers to draw essential ideas, issues and potential actions to be implemented through the policy by listening to citizens/stakeholders/experts who are therefore involved in the process. Thus, in this scenario, they have the chance to directly contribute to the planning design of a system of intervention that will impact them in the future. At the beginning, these approaches were used as a response to planning processes characterized by top-down vision and a long-term frame, particularly in rural development projects that dominated the scene from the ‘60s to the ‘80s. The more “democratic” approach of Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) is well described by Chambers, 1994 p. 953 as “a growing body of approaches and methods [used] to enable local people to share, enhance and analyze their knowledge of life and conditions; to plan; and to act”. Since then, supporting communities, associations and groups of interest have become the target of many local policies. The introduction of participatory approaches poses some specific issues like the choice of stakeholders involved, continuity of the process that should be guaranteed at all stages of a development program and the need to consider the power relationships between the different actors involved [

23]. Other issues must also be considered: those methods allow for the same importance to be attached to participants who are considered equivalent experts; it is assumed that they have an equal basis of knowledge of the issue under study [

24]. Furthermore, the key role of the workshop’s moderator is to be engaged to explain the use of the tool used to collect opinions, thoughts and proposals and to be able to guide the group. In this sense, he/she must be an expert of both participatory methods and of the workshop topic [

25]. Facilitating discussion; assisting the participants if necessary; animating the workshop; and highlighting the results, drivers and needs expressed by the participants in the work group are his/her main tasks [

26]. Application of these methods provides the possibility of using different tools to collect and systematize the results such as the proposal of a questionnaire, the scenario analysis and the use of SWOT analyses. The tool used in this study is a dynamized SWOT according to a specific technique. The analysis of Strengths and Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) is probably the most common and widely recognized tool for conducting strategic planning, representing the early stages of a process [

27]; it dates back to the ‘50s and ‘60s, since the efforts at Harvard Business School to analyze case studies [

28]. This framework has enjoyed outstanding popularity among both researchers and practitioners, since Kenneth Andrews in 1971 influenced the popularization of the idea that good strategy means ensuring fit between threats and opportunities coming from outside and internal characteristics of a firm (business policy). Since then, the SWOT analysis is a widely used tool for investigating internal and external environments in order to attain a systematic approach and support for decisions in many fields [

29]. Even if Hill and Westbrook (1997) [

30] in the late ’90s stated that it was time for a product recall, the method was implemented in many different fields and the field in which SWOT is used the most is agriculture and its sidelong fields (business and industry plans). Public institutions also started using similar methods to outline the internal and external factors relevant to their strategic planning process. During the 1980s, local governments and public institutions applied strategic planning methods to regional development and municipal planning [

31,

32]. The matching of specific internal and external factors provides a strategic matrix: internal factors are within the control of a specific system (organization or program) under study, while the external factors are out of the system’s control, such as economic and political factors, new technologies and market competition.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Area Under Study

Friuli Venezia Giulia is a small region located in the far northeast of the Italian borders of Central Europe (Austria) and looks toward Eastern Europe (Slovenia) in a privileged position of proximity to a potential market of growing interest. With about 1.2 million inhabitants and four provinces (Trieste, Udine, Pordenone and Gorizia), it covers a territory of 7858 square km (

Figure 1). Over the last decades, significant changes have occurred in its production structure. In the past, this region was characterized by a very poor economy and this had a large impact on the phenomenon of emigration. During the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Port of Trieste was the main outlet to the Adriatic Sea for Austria; then, during the ′50s–′60s large-scale changes affected both the primary and the secondary sectors. Today, the per-capita income exceeds the national average and it is among the highest in Northern Italy, even if the economic weight of the regional value added is rather modest, about 2.1% of the total national added value. In Friuli Venezia Giulia, the agricultural sector accounts for about 2% of the total regional added value (the industry contributes about 26% and the services contribute about 72%) and affects a rather limited portion of the territory as only 38% of the land is middling [

33] (Istat). The larger part of the territory, in fact, is covered by mountains with very limited lands devoted to agricultural practices as 43% of it is mountainous and 19% is hilly. The differences between mountains and plains are still very strong today, both with regard to infrastructure and production activities and with respect to the socioeconomic situation (depopulation phenomenon). The territorial configuration from the population point of view is rather homogeneous as there is no strong polarization towards a single urban center. Most of the 500 thousand employees are employed in the service sector (67%), with only 3% of those employed work in the primary sector [

33,

34].

According to data from the 6th Agricultural Census [

24], the total Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA) corresponds to just under 220 million hectares, down by 7.6% compared to the year 2000, with an incidence of 1.7% on the national level. The land concentration process has led to an increase in average company size, which is around 10 hectares/farm. Contraction of the cultivated areas was lower than the decrease in the number of farms, which is around 22 thousand (−33% with respect to the year 2000). The main crops that represent three quarters of the regional UAA are arable crops (cereals, industrial and fodder plants) and grapevines. Livestock farms are about 14% of the total, with a prevalence of cattle and pork breeding. The region is characterized by a high diversification both in terms of agricultural production and dimension of the productive systems. In fact, in some cases, they are structured and well organized in supply chains (e.g., pig meat belonging to the District of San Daniele ham or the renowned vineyards for the wine sector), while other sectors are more fragmented and consist of a variety of subsystems that express themselves in different production methods, different socioeconomic relations with the stakeholders, and different marketing and trade strategies [

35].

Since the ‘70s, the agricultural and agri-food system as well as the rural areas in general have had to face a process of industrialization and tertiarization that has led both to high specialization for some productions (high-quality assurance schemes) and to the need for preserving typical local productions (even niches). The strong territorial identity, although positive and characterizing, can become a limit when, instead of looking at technological and sustainable development (production/process/management innovations), it induces the production system to remain anchored in the past by limiting its scope to the local market. In this socioeconomic context, a further element to take into account is its poor capacity to create networks between subjects that operate in the same sector, thus reducing the possibilities of spreading sustainable innovations not only related to technological implementation but also related to farm management. To this effect, in addition to the aforementioned historical elements, there are some important issues to be considered: (a) the system is characterized by a small farm size that does not allow an increasing in production volumes and that produces low results in the competitive market; (b) low investments are made both in production and product innovation and in business management innovation; and (c) little attention is paid to research and development so far as well as to the promotion and communication of quality productions. The open issues are related on one hand to the problems connected with the marketing of agri-food products and on the other hand to the need to define a clear and consistent public support framework with desirable growth prospects for the near future.

3.2. The Rural Development Policies Supporting Innovation

The Rural Development Policy interventions through the transversal objectives of innovation and cooperation together with mobilization of the partnership are two of the most innovative assets to work with regional programming 2014–2020. The most important keywords for the policy round at the regional level are quality, environment and training. Considering priority 1 of the Friuli Venezia Giulia RDP 2014–2020 [

36], it is possible to highlight the following considerations: new investments in innovative, sustainable production systems supported as well as the transfer of knowledge from the research institutions to the productive world through the European Partnership for Innovation (EIP) projects. Priority 1 (P1) is designed to foster innovation, sustainable innovations, cooperation and the development of the knowledge base in rural areas and has two focuses: (a) to stimulate innovation and knowledge in rural areas and (b) to strengthen the links between agriculture and forestry, on the one hand, and research and innovation, on the other, in the general objective of strengthen research, development technological and sustainable innovations. The innovation approach for programming 14–20 is different from the one adopted over the past fourteen years. In fact, in the last two programming periods, the interventions were very constrained. Now, they are structured according to a broad horizon based on a system approach aiming at involving all the knowledge network actors: farms, research institutions, consulting and training. Furthermore, as the agricultural research is regulated by norms and specific laws also at the regional level, in Friuli Venezia Giulia, since 2005, a regional law dedicated to Innovation n. 26/2005 granted contributions in the field of innovation, scientific research and sustainable technological development in order to develop the needs assessment that the Friuli Venezia Giulia (FVG) experiences within the involvement of the local Partnership during the planning phase of the RDP 2014–2020 when an overall pairwise SWOT has been applied to identifying needs. The results presented here come from a specific thematic table involving experts and stakeholders around priority 1—innovation, training and advisory—focus area 1a—fostering innovation, sustainable innovations, cooperation and development of the knowledge base in rural areas.

3.3. The Method Applied to Dynamized the SWOT

This study uses a participatory approach to identify the main drivers and needs about knowledge transfer and innovation—in particular, in relation to fostering innovation, sustainable innovations, cooperation and development of the knowledge base in rural areas. The methodology is based on a bottom-up approach in a multi-stakeholder workshop and on using a specific tool to investigate: a dynamized SWOT. The implementation of SWOT is then considered as part of the strategy-building process. Even if the SWOT analysis is considered a very good method to diagnose and evaluate a system and even though it is widely applied to describe a context and to identify its needs, usually, it is the result of an analysis conducted by an expert or a group of experts rather than the product of a real interaction between policy-makers and policy-beneficiaries. Usually, the aim of applying the SWOT analysis in a strategic planning process is to develop and adopt a strategy resulting in a good fit between the internal and external factors or to be used when an alternative strategy suddenly emerges and the decision context relevant to it has to be analyzed [

37]. The SWOT matrix consists of four combinations known as the maxi-maxi (strengths/opportunities), maxi-mini (strengths/threats), mini-maxi (weaknesses/opportunities) and mini-mini (weaknesses/threats) [

38]. The main advantage of SWOT analysis is its simplicity [

11], while among its shortcomings, there is a list of factors relying on subjective perspectives of experts when conducting brainstorming sessions and the lack of relations or prioritization among the factors of the four matrix groups [

39,

40,

41]. If used correctly, the SWOT can provide a good basis for successful strategy formulation [

42], but its conventional formulation could generate little effects. The main limitations and issues which affect the whole process in using a conventional SWOT are as follows:

- −

It could merely be a list of factors belonging to the four groups of the SWOT Analysis without pinpointing the most significant one or the most important factors that could affect the analysis and therefore the strategy [

43].

- −

It is not possible to assess the fit between SWOT factors and decision alternatives.

- −

The qualitative/quantitative information available to draw a good picture of the system may not be appropriate, as they rely on the choices made by who draws up the SWOT (subjective choices).

- −

The expertise and capabilities of the actors involved in the planning action may be limited.

3.4. Workshop Design and Data Collection

The paper draws attention on a direct experience of process management realized in Friuli Venezia Giulia during the planning phase of the Rural Development Program 2014–2020 now in place. The stakeholders involved in the workshop at the end of December 2013 (18–20 December) belong to different groups of interest. The partnership, consisting of agricultural, social, environmental and research sectors’ stakeholders, belonging both to private and public institutions, involved also educational and extension/advisory organizations. The participants were considered as having the same political and economic importance. The involvement of the partnership, in compliance with the principle of multi-level governance, should consider the suggestions of the interested parties and welcome them, where relevant, for a shared action plan, enhancing the experience and skills of the identified subjects. The partnership was managed by organizing four thematic tables along with two phases: the first one was dedicated to exploration of the six priorities of the EU Rural Development Regulation; then, a SWOT analysis (by focus area) was developed (second phase). The indicators detected have been identified among the following general points that characterize the Friuli Venezia Giulia region as far as priority 1 is concerned:

- −

Strengths: (a) Good participation of the population between 25 and 64 in courses of study or vocational training, (b) high level of education of young farmers (full/high agricultural training) and (c) good regional education system;

- −

Weaknesses: (a) Low propensity of farmers to take part in training courses, (b) specific skills of farmers considered as inadequate and uncompetitive with respect to the market demand, (c) low average level of education of farmers, (d) very high-aged farmers (>55 years), (e) training offers not targeted to the needs of the sector, (f) the increasing share of young people who do not work and do not study, (g) weak relations between research and innovative enterprises, (h) fragmentation of competences of the regional advisory system, and (i) difficulties for farms in accessing risk capital and credit opportunities;

- −

Opportunities: (a) new skills, new tools and innovative services required by the market; (b) European funding and innovation programs to apply to; (c) greater chances given by the global markets; and (d) potential integration between the opportunities offered by the European Social Fund and the European Fund for Rural Development;

- −

Threats: (a) Increasing competitiveness of the markets, and (b) difficulties in access to the credit system and the general reduction in public expenditure.

Two elements were identified for each of the four SWOT sections (counting a total of 56 possible combinations for each of the 18 focus areas). The matrices were processed considering the row and column pairwise combination according to a double-reading key (rows and columns). Results coming from thematic

Table 1 on priority 1, focus area 1a is analyzed and discussed in this paper. It was made on the following indicators:

- −

Strengths: (a) Widespread information system and (b) well-organized information system;

- −

Weaknesses: (a) Little sustainable and innovative services and (b) low skills—advisory;

- −

Opportunities: (a) Ongoing and multidisciplinary training, and (b) increasing supply of specific advisory services;

- −

Threats: (a) Increasing market competitiveness and (b) poor availability of financial resources addressed to advisory services.

A discussion about the score allocation reveals how the row factors are influenced by those of the column, considering the first ones as dependent variables and second ones as independent variables. The so-called counterintuitive problem was also highlighted: when an element of weakness or threat is reinforced in its negative potential by a factor (more or less strongly), this means that the latter contributes to increasing the negativity of the combination, so the score in these cases becomes positive. Furthermore, if the case of no agreement among participants occurred (about the attribution of a score on a specific combination of factors), the score reflects the will of the majority, taking note of the situation.

There were 34 participants. The workshop was managed by a researcher who invited the participants to enjoy small groups of 5–0 people according to their expertise. The activity was held on a one-day workshop, and it was structured according to the following steps: The first step was to read the SWOT factors (internal and external). The second step was to explain the technique, and an example was proposed. The third step was to apply a pairwise comparison between the factors (overall pairwise SWOT—dynamic or relational) in order to formulate at least one requirement per focus area. To give evidence of the partnership’s perception, stakeholders were supposed to directly give their judgements using a scale of values—five-point scale (influence scores)—to detect priority factors:

- (1)

the lowest score if the row factor is strongly hindered (or cancelled) by that of the column;

- (2)

a medium low score if the row factor is hindered by that of the column (however, it develops its own effects);

- (3)

a medium score if the factor considered is independent of each other (they do not influence each other);

- (4)

a medium–high score if the row factor is incremented by the column-= factor (the effects of the first are made wider by the second); and

- (5)

the highest score if the row factor is strongly increased by the column factor.

The disadvantages of a SWOT analysis can be found in [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. In order to avoid some of these limitations, a number of quantitative methods have been developed, as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)-SWOT [

50,

51,

52,

53], Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP)-SWOT [

54] and other applications [

40]. The common factor in all these techniques is that the relative importance of the SWOT factor is determined through a pairwise comparison within and between SWOT groups. This research aims to give evidence of a dynamic approach developed on the basis of some writings of Bezzi (2005) around what he called “relational SWOT” and from a previous working paper [

55]. The effort is to dynamize the SWOT, making links and attributing relevance in terms of weight between its factors to try to overcome some of the main limitations of the conventional SWOT.

The technique used is an adaption of the AHP procedure [

56,

57,

58], considering all the factors combined with each other, regardless of their belonging to a group or another. The goal is to identify the factors that prevail over the others or those that are hindered by others and that, therefore, cannot give direction to develop a strategy. In this way, it will be possible to understand if the factors with a positive sign (strength and opportunity) or if those with negative features (weakness and threats) have the higher weight as well as to assess whether internal or external elements are perceived as drivers.

This multicriteria decision-making model allows for conversion of qualitative information into quantitative values by evaluating the weights of identifying factors in pairwise comparisons. The matrix under this method is a square matrix as follows:

where

aij is the score factor

i to

j or rather its relative importance. Therefore, if factor

i is more important than factor

j, then the score is

aij, while if the contrary is true—factor

j is more important than factor

i—then we will have the score 1/

aij (the reciprocal);

aij = 1 if factor

i is of the same importance as factor

j. The weight values are represented by a vector W given by the matrix coming from (A x vector W) (using eigenvalue λmax x W). The scale used by Saaty was from a score of 1 to 9, considering the odd numbers as pivot and even numbers as intermediate values. The authors of [

59] first prioritized the factors by group and then by evaluating different alternatives. In our study case, we directly measure the importance of each SWOT factor and any alternatives have been detected.

4. Results and Discussion

The developed SWOT was made of two factors for each group (

Table 1). The matrix was processed considering the row and column according to the double-reading key (rows and columns). An Overall Pairwise SWOT (OP-SWOT) as an adaptation of the AHP approach was applied to the SWOT matrix. This was due to the small number of factors per group which do not allow for implementation of AHP-SWOT and for identification of the priority factors within the groups and then the overall priority factors, as shown by the works of [

57,

60].

First, a pairwise comparison of the SWOT factors was implemented combining all the factors with each other, regardless of their belonging to a group or another, starting from the rows to columns. Following the work of [

56], the AHP process was applied. The eigenvalues were calculated to derive the weights of priorities (Wi). The next step was to measure the consistency of results by the Consistency Ratio (CR). The CR should not exceed 0.10; if this is the case, then further examination is required to improve consistency. To obtain the CR, the Consistency Index (CI) was required, starting from the eigenvalues of the matrixes λ

i (I = 1, …, n). The CR was then obtained by CI and the appropriate value of a Random Consistency Index (R.I. 1 (0), 2 (0), 3 (0.58), 4 (0.90), 5 (1.12), 6 (1.24), 7 (1.32), 8 (1.41), 9 (1.45) and 10 (1.49)). In this case, the value is 1.41.

CI = (λmax − n)/(n−1)

CR = CI/R.I.

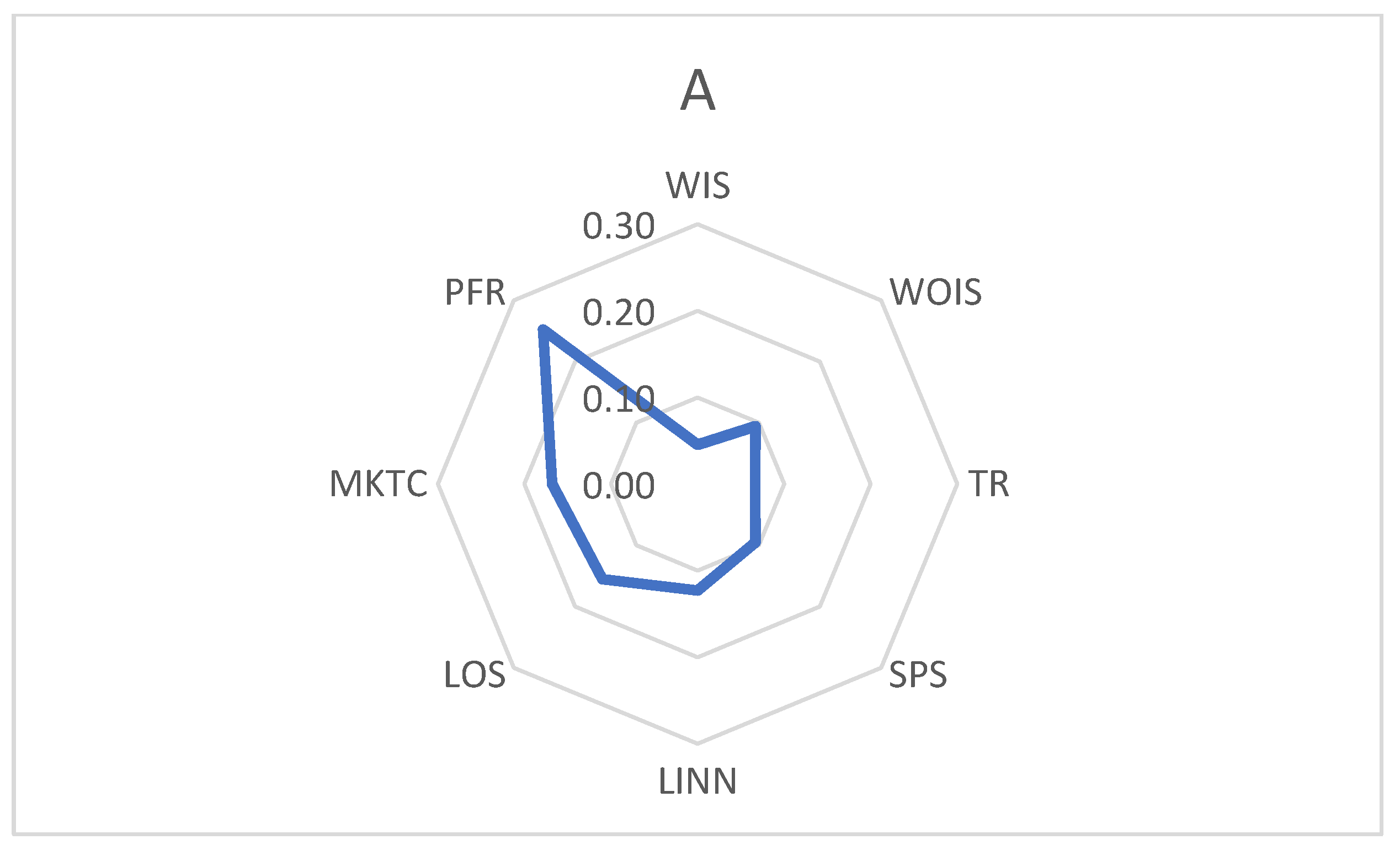

The CR around 0.10 is acceptable, even if results could achieve an even better performance in terms of consistency if some of the combinations were repeated. The priority factors belonging to the threats and opportunities sections (

Table 2) show that the higher values are for external-negative factors, in particular for threats: 25.2% is for the “Poor availability of financial resources addressed to advisory services”, followed by the “Increasing market competitiveness” with 16.8%. However, the opportunity “Increasing supply of specific advisory services” is also quite high with a 15.6%. Then, “Ongoing and multidisciplinary training” also has a considerable percentage. A graphical representation of the results is shown in

Figure 2 (blue line). These are the factors to be taken into account in order to build up a program which would include the partnership’s suggestions, as they represent the drivers on which to mainly work. Looking at the weaknesses, it is evident that they are almost of the same magnitude as the strengths, so the internal factors are almost balanced by each other and do not represent the drivers on which to focus efforts.

The stakeholders involved in this case study have welcomed the SWOT analysis, providing suggestions and actively contributing to identification of the needs of the area under study to develop a good strategy for RDP 2014–2020. The statements of the stakeholder’s contributions provided some key highlights and recommendations. Even though the high level of education (young people), the presence of some research centers of excellence in the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region and a regional law dedicated to innovation, the areas to improve upon were the little availability of financial resources addressed to advisory services and the increasing competitiveness of the markets, especially those of Eastern Europe. Furthermore, the fragmentation of the training offer and the low sustainable innovative services to farms, together with the need for continuous training and multidisciplinary courses, are also considered important drivers upon which to work for a good strategic planning. Lifelong education and training both for advisors and farmers’ needs are a priority. New skills and competences (for learning and innovating) are perceived as very important to enable them to cope with the evolving market rules, changing legislation, consumers and market dynamics. As the workshop could not include everything that may have an impact on the region, it is still desirable that it contains some of the main key factors that can actually be influenced by the program under observation; in this sense, the role played by the SWOT presented in this paper is to be considered part of the strategy-building process implemented and based on a bottom-up participatory approach.

Focus area 1a of priority 1 is designed to foster innovation, cooperation and development of the knowledge base in rural areas. Through this focus area, member states are expected to provide to their stakeholders a flexible package of soft measures related to advice, training, cooperation and knowledge transfer. Performing pairwise comparisons between SWOT factors as in the AHP and then analyzing the results by means of the eigenvalue could give to decision makers quantitative information about this specific theme [

57,

61]. In this case, the decision makers were able to prioritize the factors, looking at two threats requiring higher attention. On these results (the second point also in some previous studies [

62], the needs identified by the participants for the strategy-building process were the following:

- −

to activate advisory measures for both agricultural companies and users/consultants to face market competitiveness (increasing funds needed);

- −

to guarantee a collaborative environment for training and training consultancy in the field of business services;

- −

to support startups and professional companies who could probably be more competitive; and

- −

to study a mechanism for the evaluation of consultants: system accreditation for a quality assurance scheme of services.

The interventions identified in the regional strategy for Friuli Venezia Giulia RDP 2014–2020 aimed at satisfying those needs. The RDP then included measures with adequate support to promote the use of selected and specialized advisory services to improve economic, environmental, and technical and administrative management of farms. Plans which could guarantee effective and efficient investments as well as the search for high standards of advisory services were also considered a priority. The objectives will be achieved with the provision of a business consulting service that could support agricultural, forestry and Small-Medium sized Entrepreneurs. Facilitating the dissemination and transfer of data and information of a technical, economic and regulatory nature, together with training and updating professional consultants were also among the main goals. The use of advisory services was then introduced as compulsory and as an alternative to the training actions described in some other interventions, such as those related to the beneficiaries of the integrated supply chain projects or the package dedicated to young farmers [

36].

In its common use, the SWOT has some weaknesses that could be avoided by a decision analysis method: in this study, a SWOT was presented through dynamization referring to the AHP technique. This is a suited approach to dealing with the factors in SWOT analysis. In this information processing, one of the recommendations is to limit the number of factors to ten [

56,

57,

58]; in this case, eight factors are combined. Some authors [

58,

60,

61] proposed a pairwise combination for each of the four groups of the SWOT, deriving the relative priorities of each factor within the SWOT groups and then an overall factor weight. In this study, each factor is combined with all the others, giving directly an overall priority factors weight as a result. The priority factors are used to support the choice of strategy, and the results obtained can make it possible to compare internal and external capabilities because all the factors are on the same numerical scale. According to the experience in the Friuli Venezia Giulia workshop, the decision makers were involved in a more pragmatic way to analyze the situation. One of the limitations of this SWOT implementation is the number of factors included in each group. To further the analysis, a wider number of factors could allow a more tailored SWOT, increasing the information available and covering a wider range of items which could contribute to better formulation of the SWOT. Another possible exploration could be the scenario modeling approach over time [

38] with a dynamic SWOT where changes in internal and external factors over time are included. The SWOT analysis performed in this study case could allow the local administration to start an inside analysis based on the evidence of balancing the internal elements of the regional environment as well as considering the external environment. These results support the idea that the SWOT analysis could bring about the beginning of a learning process; the RDPs are part of a national process. The stakeholders involved in Friuli Venezia Giulia partnership were also invited to broaden their thoughts to highlight the most important needs starting from the main drivers. They stressed the importance of the role played by both the farmers’ and the advisory system (consultants). Participants also highlighted the need to pay greater attention to the link between the agricultural world and the world of research for development of sustainable innovations capable of developing a concrete impact on farms. For each topic covered during the workshop, the reference to young people as a driving force for the future was recurrent. In particular, the following needs have been clearly highlighted:

- −

Generational renewal: facing different channels to support young farmers but including older farmers in receiving subsidies;

- −

Start-up: to differentiate further to favor start-up, financing all new settlements;

- −

improving networks by linking the research, training and advice systems;

- −

improving the skills of farmers in order to make them capable of seizing the opportunities to develop sustainable innovations;

- −

improving the skills of advisory/consultants to achieve a higher level of technical/information flow (central role of research and training centers);

- −

disseminating innovation to promote the competitiveness of famers through improvement of sustainability and eco-compatibility; and

- −

enhancing the possibility of using direct training methods aimed at the exchange of experience (rather than lectures).

The areas of interest in which these needs should be addressed have been explained by the participants and can be summarized as follows.

4.1. Interactive Innovation Between Research, Advisory System and Farmers

Among the needs and priorities, interactive exchange between researchers, consultants and farmers to enhance sustainable innovation is perceived as very important, especially when organic farming is concerned (an in-depth knowledge of integrated and organic production methods is needed). Another area of interest is the wood–wood-energy supply chain, which is one of the most significant fields for the region to increase sustainable innovation, especially in the production process. It is also considered important to study soils and to know the chemical evolution of nitrogen compounds present in livestock waste once distributed in the soil, as the seasons change. It is necessary to adopt correct use of livestock waste in order to achieve an improvement in soil fertility. Another theme highlighted is that of the agricultural farm and its connection with renewable energies and marketing policies. With regard to renewable energies, it has been pointed out that waste from the wine sector (pruning waste and pomace) could also be used. For the environment, the emphasis has been placed on environmental sustainability and the maintenance and restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity linked to agricultural-forestry practices. As far as agri-food products are concerned, the importance of creating innovative products was stressed, paying attention to the processing phase and to the quality standard (e.g., milk and meat). Finally, the themes of biotechnology, the short supply chain and the role of social farming were suggested as future issues to be considered by the program.

4.2. Specialist Advice

This need was explained as a need of being supported by the highest skills of specialist in the advisory field of economic management of agricultural enterprises aiming at strengthening a kind of corporate culture to allow improvements in the financial issues’ management (e.g., industrial plan, costs analysis and management of the farm’s financial statements). The training and selection of consultants who support farmers should then be able to provide both specialist technical assistance to the production and to the marketing issues. The management of agricultural risk and credit is another important need expressed by the participants. The issue of sustainable innovations and development is once again mentioned as a priority both at the environmental level and at the social and income levels (integrated protection of agricultural crops, diversification of production, organic farming and renewable energies). Forest management is also reported as an issue to be considered. Further topics for discussion are milk production, agronomic research and sustainable certifications. Finally, the issue of young entrepreneurs is given priority.

4.3. Specialist Training

The most important topics indicated in the field of specialist training are the economic and financial management of the farm, including forestry. Attention is also paid to the themes of marketing, communication and internationalization as well as to the search for new market opportunities through new productions. The training of young entrepreneurs as well as agro-industrial technicians and cooperative management groups are also considered important. As for environment and sustainability, the maintenance and restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity related to agricultural-forestry practices, organic farming and crop protection are identified as priority themes.

4.4. Product Innovation, Integration of EU Funds and Interactive Innovation in Less Favored Areas

A very important issue to be addressed is the integration between territory, tourism, the environment and the enhancement of the agri-food system. Enhancement of the landscape, protected areas and green practices as well as agricultural and agri-food tourism are also indicated as fundamental. Furthermore, the topic of product improvement has been proposed: the adoption of innovative packaging to improve preservation and presentation of the product and its marketing and selling-related issues. Another interesting topic discussed is the integration of different EU funds to enhance rural areas. Resources for innovation in less favored areas (characterized by poor infrastructures, poor Information Technology (IT) connections and climate adversity) are also considered urgent for the Friuli Venezia Giulia region.

4.5. Policy Implications

Further research should be developed for the next programming period in order to find confirmation of these results. However, from what has emerged, it is possible to trace some policy suggestions that focus on the following points:

- −

ensuring increased “on-demand” sustainable innovations by empowering both the farmers and their organizations (public and private stakeholders, and interactive exchange between researchers, advisors and farmers);

- −

providing farmers with more tools (technical, advisory and training) to expand their capacity to institutionalize innovations, making them durable over time and not dependent on the program, in accordance with [

62];

- −

enhancing a multi-stakeholder participatory approach by an ongoing system of workshops to ensure updates and by making stable a monitoring process: facilitating the possibility to incorporate farmers’ knowledge and proposals into the program’s agenda, consistent with what has been argued by [

63];

- −

taking into account institutional innovation as well, which may be needed in order to ensure communication and transparency and to improve relations between institutions and farmers [

19,

63];

- −

redefining the process of farmers’ education with a permanent learning process, encouraging the development of new skills and competences (for learning and innovating) [

19]; and

- −

designing policies that can ensure both technical and economic (financial) contributions to development of successful sustainable innovations and successful policies: more efficient and effective use of resources, also highlighted in the work of [

26].

Farmers will innovate to sustain and improve their productivity and performance if there is a “good environment” to realize such intentions. Some of the issues arisen during the workshop are, in fact, those related to the necessity of being part of an effective social organization [

64]. This could support better communication at the community level because it would be a product of social links among stakeholders (a confirmation of the [

62] findings). They stated that innovation is then a product of social negotiation and that the spread of innovation is a product of good effective social organization and communication at the community level. Furthermore, adding the farmers’ and the stakeholders’ proposals to the agenda seems to be a guideline to be followed not only because of the EU Commission commitment but also because organizational innovations are needed to move agriculture towards sustainable innovations as stated by [

19]. Building institutional linkages, maintaining communication and monitoring the process are some of the points highlighted as well in the study of [

64]. The consequences of such processes would probably lead to better governance. The experience in Friuli Venezia Giulia indicates the high potential contributions of all the actors involved in building a good/fitted strategy for a policy that will impact the area where they are settled or live. The multi-stakeholder workshop data demonstrates that collaboration represents a key factor and that social mobilization could represent a useful tool in designing local policies in rural area. More effort should be done both at national and regional level: a document provided by [

65] gives some guidelines to set up a common working path between the Italian Ministry of Agricultural, Agri-food and Forestry Policies and the Italian regions to design the next Strategic Plan. Some challenges are still open, like the low financial resources available or how to improve the governance of both single farmers and of intermediary actors like associations or consortia (institutional innovation). Further research should be carried out to support these findings especially from the CAP post 2020 perspective, which gives confirmation and emphasizes the innovation issue.