Strategic Decisions for Sustainable Management at Significant Tourist Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

Theoretical Background

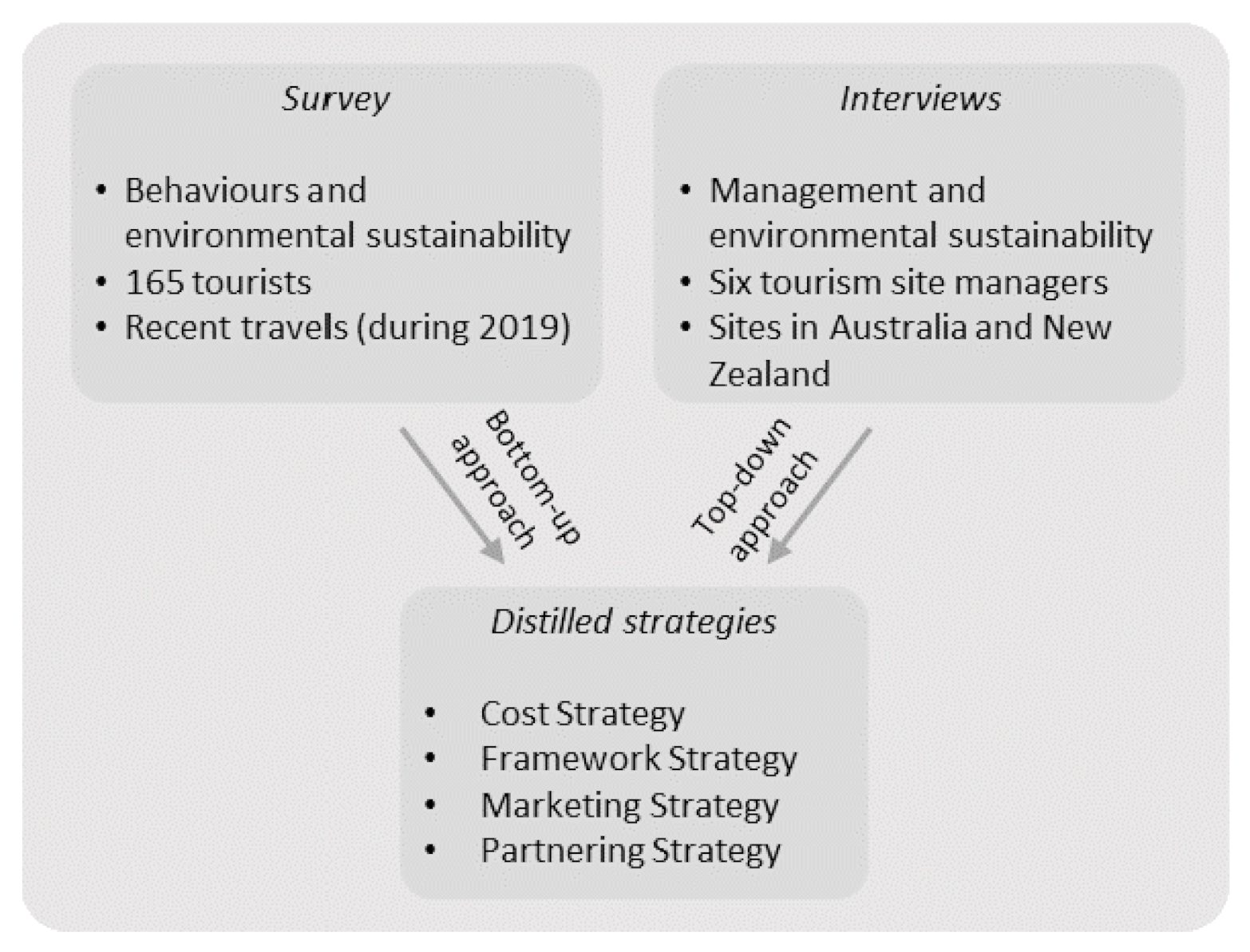

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results Analysis

3.1.1. Question 1—Do You Consider the Sustainability of Tourist Sites Prior to Visiting?

3.1.2. Question 2—Was Your Decision to Visit Tourist Sites in the Last Year Informed by the Environmental, Cultural, or Historical Significance of the Site?

3.1.3. Question 3—Would You Adjust Your Behaviours If You Had More Information about the Sustainability of the Site?

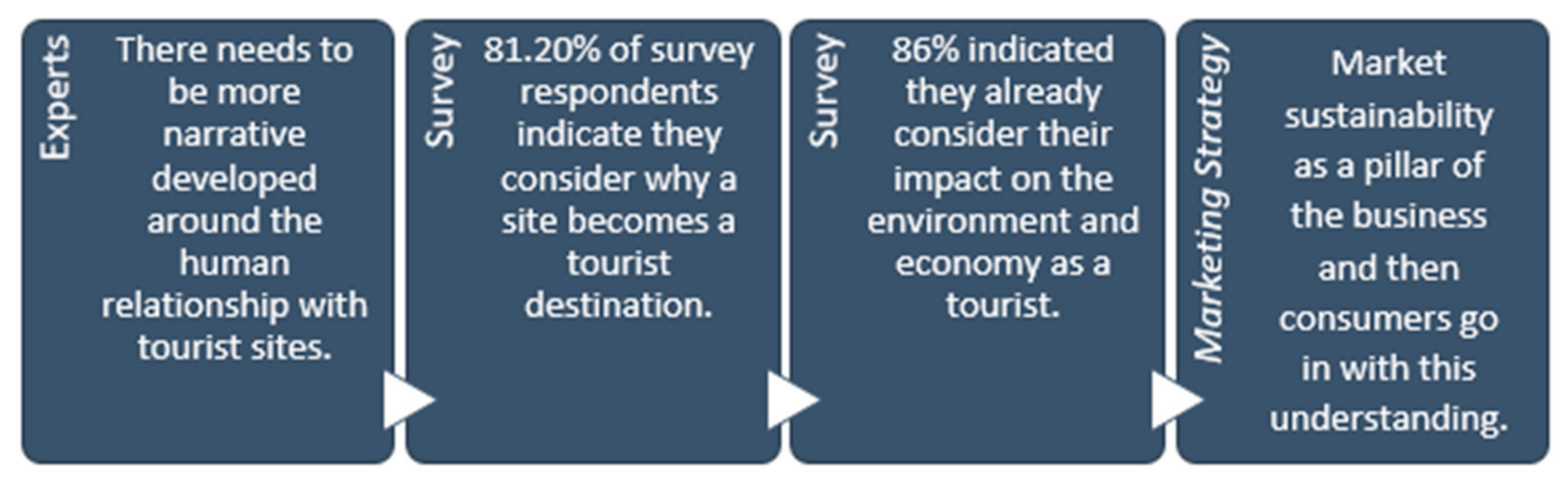

3.1.4. Question 4—Do You Think about Why a Site Becomes a Tourist Destination?

3.1.5. Question 5—Do You Consider Your Impact on the Local Environment and Economy as a Tourist?

3.1.6. Question 6—Would You Be More Inclined to Visit a Tourist Site If You Knew It Was Going to Disappear in the Coming Years?

3.1.7. Question 7—Do You Think Your Decisions as a Tourism Consumer Would Change If You Knew More about Sustainability?

3.1.8. Question 8—Do You Think Tourist Sites Should Have Sustainability Management Plans in Place?

3.2. Interview Analysis

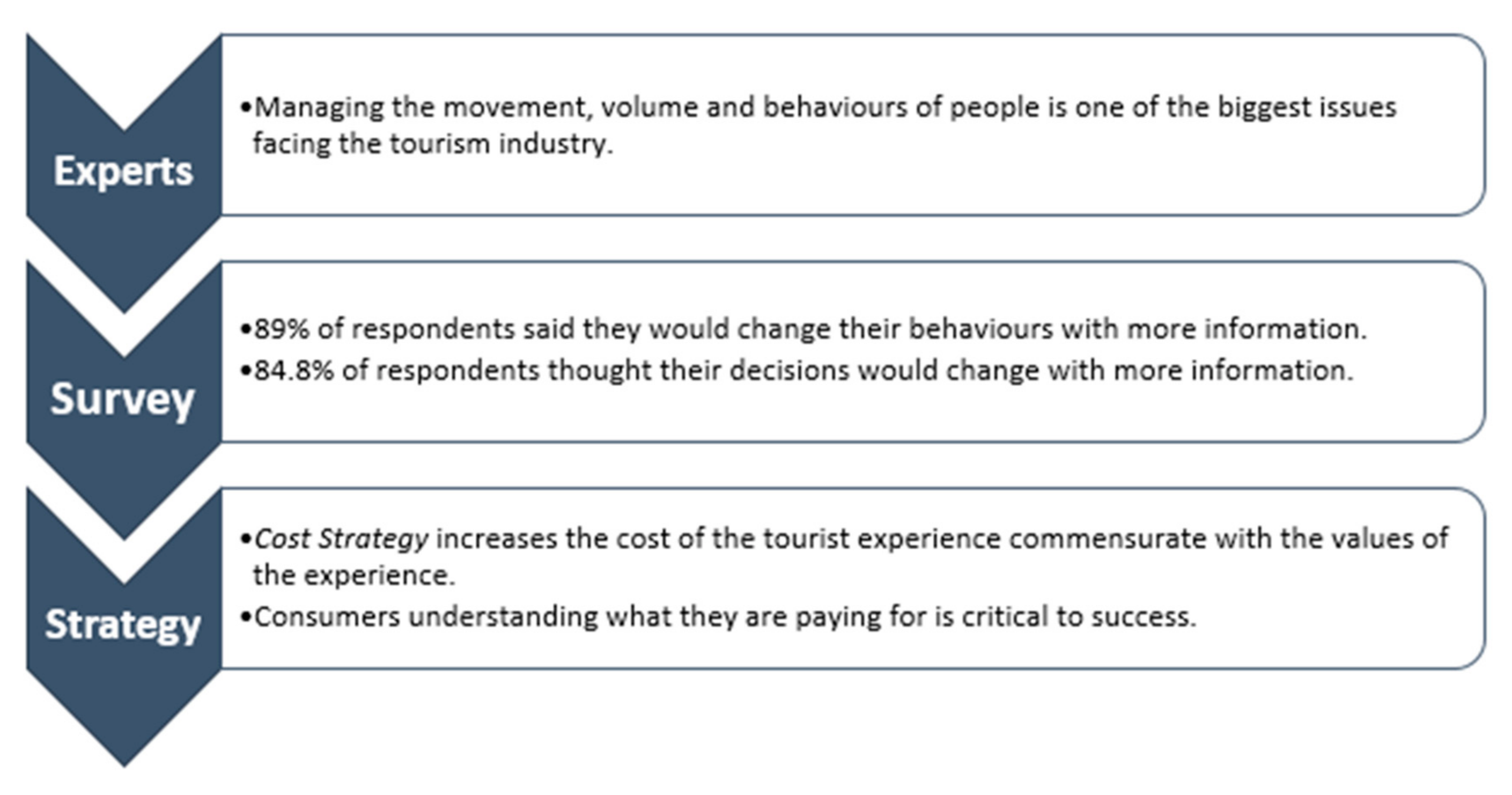

3.2.1. Question 1—What Do You Think Are the Biggest Issues Facing the Tourism Industry in Regard to Sustainability?

3.2.2. Question 2—Do You Think Tourism Could Be Considered a Sustainable Industry?

3.2.3. Question 3—Why Do You Think Many Tourist Sites Do Not Have Sustainability Management Plans in Place?

3.2.4. Question 4—Do You Think Sustainability Is Approached Differently in Regard to the Type of Tourist Site (i.e., Cultural, Environmental, Historical)?

3.2.5. Question 5—What Balance Should Be Struck between Managing the Sustainability of the Tourist Site Versus the Sustainability of Adjacent Issues such as Local Economies and Cultural Integrity?

3.2.6. Question 6—What Could Be Done to Influence the Tourism Industries’ Response to Sustainability?

3.2.7. Question 7—How Much Weight Do Human Behaviours Carry in Regard to Sustainability and How Can We Best Influence This?

4. Discussion—Management Strategies for Sustainable Tourism

4.1. Cost Strategy: Pricing Tourism Experiences According to a Value Proposition

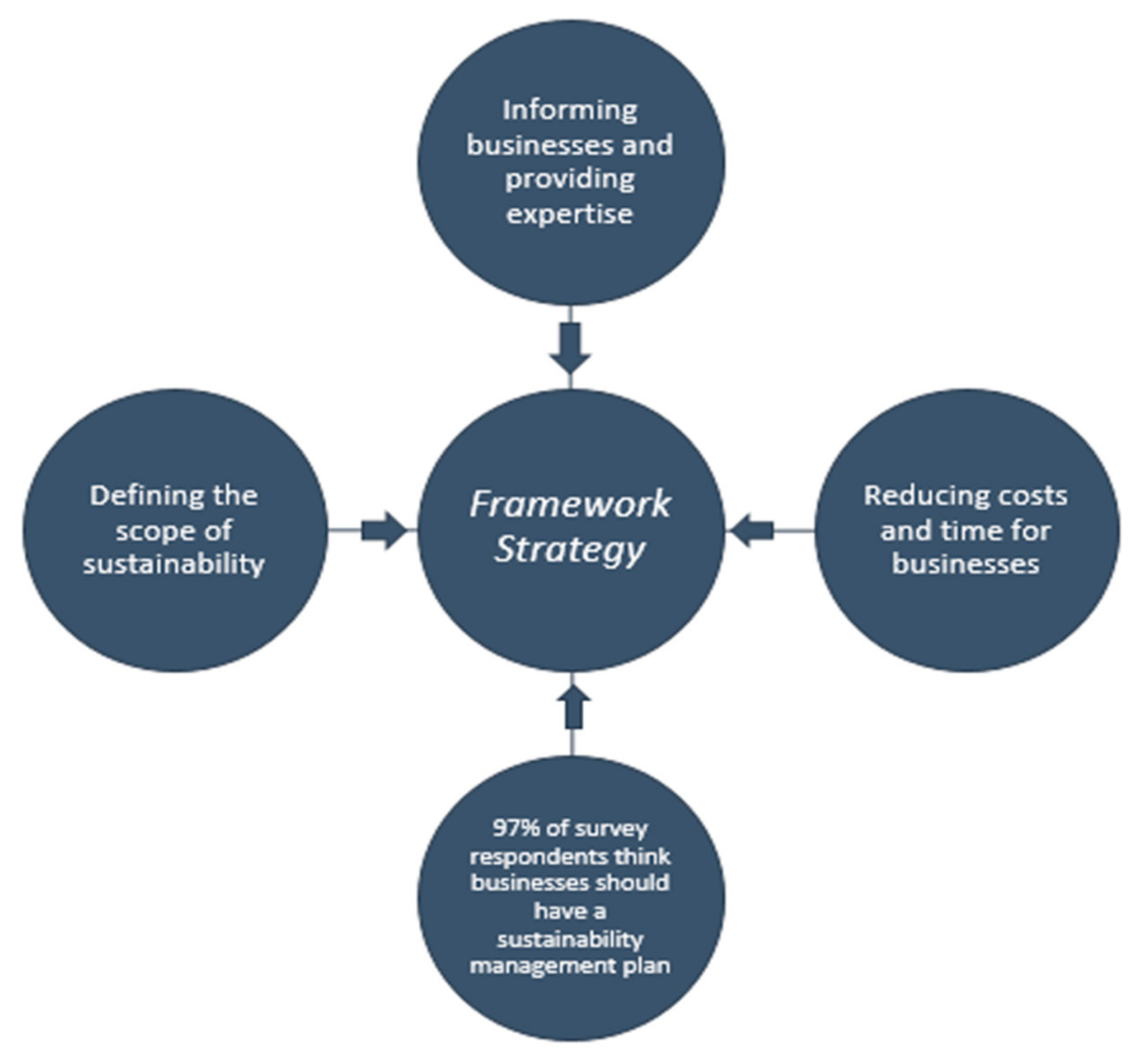

4.2. Framework Strategy: Guiding Businesses to Operate Sustainably

4.3. Marketing Strategy: Advertising the Importance of Sustainability to the Tourist Experience

4.4. Partnering Strategy: Working with Local Custodians to Enhance Value

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kummerer, S. Eco-Friendly Tourism is Becoming a Movement, and More Vacationers are Buying into the Concept. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/27/eco-friendly-tourism-is-becoming-a-movement-and-more-vacationers-are-buying-into-the-concept.html (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Coghlan, A. Tourism Is Four Times Worse for the Climate than We Thought. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2168174-tourism-is-four-times-worse-for-the-climate-than-we-thought/ (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Becken, S.; Simmons, D.G. Understanding energy consumption patterns of tourist attractions and activities in New Zealand. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. Tourism and Transport in New Zealand: Implications for Energy Use. 2001. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35459093.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Stone, G.W. For Travelers, Sustainability Is the Word—But There Are Many Definitions of It. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/features/what-sustainable-tourism-means/ (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Goodwin, H. The challenge of overtourism. Responsible tourism partnership. Work. Pap. 2017, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vicens Ballester, L. Overtourism, Impacts and Policies. Asian Perspectives: The Case of Boracay. Diploma Thesis, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Palma, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrittella, M.; Bigano, A.; Roson, R.; Tol, R.S. A general equilibrium analysis of climate change impacts on tourism. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. Good Weather or Your Money Back: How Climate Change Could Transform Tourism. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-01-30/how-climate-change-will-change-tourism/9312674 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Hambira, W.L. Botswana tourism operators’ and policy makers’ perceptions and responses to the tourism-climate change nexus: Vulnerabilities and adaptations to climate change in Maun and Tshabong areas. Nord. Geogr. Publ. 2017, 46, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Vora, S. Travel Tackles Climate Change. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/02/climate/travel-tackles-climate-change.html (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Liobikiene, G.; Balezentis, T.; Streimikiene, D.; Chen, X. Evaluation of bioeconomy in the context of strong sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, S. A sustainable tourism policy research review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, K. Ecotourism: At One with Nature. Available online: https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/travel/travel-destinations/2009/09/ecotourism-at-one-with-nature/ (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Epler, B. Tourism, the economy, population growth, and conservation in Galapagos. Charles Darwin Found. 2007, 1, 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mullis, B. The Growth Paradox: Can Tourism Ever Be Sustainable World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/08/the-growth-paradox-can-tourism-ever-be-sustainable/ (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Kiron, D.; Kruschwitz, N.; Haanaes, K.; Reeves, M. Joining forces: Collaboration and leadership for sustainability. Mit Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 56, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Mair, J. Ecosystem services approach for community-based ecotourism: Towards an equitable and sustainable blue economy. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1665–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Garrod, B. Destination management: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleśniewicz, P.; Pytel, S.; Markiewicz-Patkowska, J.; Szromek, A.R.; Jandová, S. A Model of the Sustainable Management of the Natural Environment in National Parks—A Case Study of National Parks in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Higham, J.; Lane, B.; Miller, G. Twenty-Five Years of Sustainable Tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking Back and Moving Forward. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B. Sustainable Tourism: Theory and Practice; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management; Cabi: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sofield, T.H. Empowerment for Sustainable Tourism Development; Emerald Group Publishing: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. Barriers to implementing sustainable tourism policy in mass tourism destinations. MPRA Paper 2009, 1, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, G.W. For Travelers, Sustainability is the Word—But There are Many Definitions of It. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/features/what-sustainable-tourism-means/#close (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Shafiee, S.; Ghatari, A.R.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Jahanyan, S. Developing a model for sustainable smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maingi, S.W. Sustainable tourism certification, local governance and management in dealing with overtourism in East Africa. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 532–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Fazey, I.; Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C.; Robinson, G.M.; Evely, A.C. Integrating local and scientific knowledge for environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1766–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Soria, J.A.; Núñez-Carrasco, J.A.; García-Pozo, A. Environmental Concern and Destination Choices of Tourists: Exploring the Underpinnings of Country Heterogeneity. J. Travel Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. Overtouristified cities: An online news media narrative analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1805–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertzer, J.D.; Zeitzoff, T. A bottom-up theory of public opinion about foreign policy. Am. J. Political Sci. 2017, 61, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J. Innovation in governance and public services: Past and present. Public Money Manag. 2005, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Axsen, J.; Sorrell, S. Promoting novelty, rigor, and style in energy social science: Towards codes of practice for appropriate methods and research design. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 45, 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltean-Dumbrava, C.; Watts, G.R.; Miah, A.H.S. “Top-down-bottom-up” methodology as a common approach to defining bespoke sets of sustainability assessment criteria for the built environment. J. Manag. Eng. 2014, 30, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D.; Dougill, A.J.; Mabee, W.E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becken, S. The role of tourist icons for sustainable tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E.A. Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. The evolution of tourism and tourism research. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2015, 40, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U. Combining qualitative and quantitative methods in research practice: Purposes and advantages. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 293–311. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Barriers to integrating quantitative and qualitative research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, M.; Sierra, J.J. Open-versus close-ended survey questions. Bus. Outlook 2016, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ponto, J. Understanding and evaluating survey research. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2015, 6, 168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Passafaro, P. Attitudes and tourists’ sustainable behavior: An overview of the literature and discussion of some theoretical and methodological issues. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgolli, S.; Zaiem, I. The responsible behavior of tourist: The role of personnel factors and public power and effect on the choice of destination. Arab Econ. Bus. J. 2018, 13, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.; Crompton, J.L. Attitude determinants in tourism destination choice. Ann. Tour. Res. 1990, 17, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Knezevic Cvelbar, L.; Grün, B. A sharing-based approach to enticing tourists to behave more environmentally friendly. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivacek, J.; Crano, W.D. Vested interest as a moderator of attitude–behavior consistency. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClimon, T.J. The Future of Preservation Is Sustainable Tourism. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/timothyjmcclimon/2019/12/09/the-future-of-preservation-is-sustainable-tourism/#51df2d8a6ea5 (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- Piggott-McKellar, A.E.; McNamara, K.E. Last chance tourism and the Great Barrier Reef. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Last Chance Tourism: Is This Trend Just Causing More Damage? Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/last-chance-tourism-travel-great-barrier-reef-amazon-machu-picchu-a8363466.html (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Fall Diallo, M.; Diop-Sall, F.; Leroux, E.; Valette-Florence, P. Comportement responsable des touristes: Le rôle de l’engagement social. Rech. Appl. En Mark. (Fr. Ed.) 2015, 30, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.-F.; Spenceley, A.; Hvenegaard, G.; Buckley, R.; Groves, C. Tourism and Visitor Management in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Sustainability; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M. Indigenous peoples and tourism: The challenges and opportunities for sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabler, M.J.; Papatheodorou, A.; Sinclair, M.T. The Economics of Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cavagnaro, E.; George, H. The Three Levels of Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Honeywill, R.; Byth, V. NEO Power: How the New Economic Order is Changing the Way We Live, Work and Play; Scribe Publications Pty Limited: Melbourne, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tussyadiah, I.P. Toward a theoretical foundation for experience design in tourism. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. ‘Sustainable Tourism’ Is Not Working—Here’s How We Can Change That. Available online: https://theconversation.com/sustainable-tourism-is-not-working-heres-how-we-can-change-that-76018 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Kubickova, M. The role of Government in tourism: Linking competitiveness, freedom, and developing economies. Czech J. Tour. 2016, 5, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Razak, V. A framework for sustainable tourism in Aruba. Prep. Natl. Tour. Counc. Aruba Minist. Tour. Transp. Dec. 2004, 1, 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Laitamaki, J.; Hechavarría, L.T.; Tada, M.; Liu, S.; Setyady, N.; Vatcharasoontorn, N.; Zheng, F. Sustainable tourism development frameworks and best practices: Implications for the Cuban tourism industry. Manag. Glob. Transit. 2016, 14, 7. [Google Scholar]

- dos Anjos, F.A.; Kennell, J. Tourism, governance and sustainable development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. Sustainable Tourism in New Zealand: The Chinese Visitors’ View. Master’s Thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R.; Pearce, T. Tourism, marketing and sustainable development in the English national parks: The role of national park authorities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, S. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwinuka, O.H. Reviewing the role of tourism marketing in successful sustainable tourist destinations. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lansing, P.; De Vries, P. Sustainable tourism: Ethical alternative or marketing ploy? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.F.; Menzies, C.R. Traditional ecological knowledge and indigenous tourism. Tour. Indig. Peoples Issues Implic. 2007, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kunasekaran, P.; Gill, S.S.; Ramachandran, S.; Shuib, A.; Baum, T.; Herman Mohammad Afandi, S. Measuring sustainable indigenous tourism indicators: A case of Mah Meri ethnic group in Carey Island, Malaysia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M.; McLennan, C.-L. Indigenous tourism in Australia: Time for a reality check. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiutsi, S.; Mudzengi, B.K. Community tourism entrepreneurship for sustainable tourism management in Southern Africa: Lessons from Zimbabwe. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Bushozi, P.M. Towards sustainable cultural heritage management in Tanzania: A case study of Kalenga and Mlambalasi sites in Iringa, southern Tanzania. S. Afr. Archaeol. Bull. 2014, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

| Survey Questions |

|---|

|

| Interview Questions |

|---|

|

| Survey Questions (165 Surveyed People) | Yes (%) | No (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Do you consider the sustainability of tourist sites prior to visiting? | 47.9 | 52.1 |

| 2. Was your decision to visit tourist sites in the last year informed by the environmental, cultural, or historical significance of the site? | 69.5 | 30.5 |

| 3. Would you adjust your behaviours if you had more information about the sustainability of the site? | 89.0 | 11.0 |

| 4. Do you think about why a site becomes a tourist destination? | 81.2 | 18.8 |

| 5. Do you consider your impact on the local environment and economy as a tourist? | 86.0 | 14.0 |

| 6. Would you be more inclined to visit a tourist site if you knew it was going to disappear in the coming years? | 78.8 | 21.2 |

| 7. Do you think your decisions as a tourism consumer would change if you knew more about sustainability? | 84.8 | 15.2 |

| 8. Do you think tourist sites should have sustainability management plans in place? | 97.0 | 3.0 |

| Interview Guiding Questions | Interviewed Field Experts/Representatives |

|---|---|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mackay, R.M.; Minunno, R.; Morrison, G.M. Strategic Decisions for Sustainable Management at Significant Tourist Sites. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218988

Mackay RM, Minunno R, Morrison GM. Strategic Decisions for Sustainable Management at Significant Tourist Sites. Sustainability. 2020; 12(21):8988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218988

Chicago/Turabian StyleMackay, Robert M., Roberto Minunno, and Gregory M. Morrison. 2020. "Strategic Decisions for Sustainable Management at Significant Tourist Sites" Sustainability 12, no. 21: 8988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218988

APA StyleMackay, R. M., Minunno, R., & Morrison, G. M. (2020). Strategic Decisions for Sustainable Management at Significant Tourist Sites. Sustainability, 12(21), 8988. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218988